User login

LOS ANGELES – In patients using triptans for the acute treatment of migraine, the impact on headache-related disability of switching or adding medications depends on the frequency of attacks and the type of medication, new data show.

Dr. Richard B. Lipton and Dawn C. Buse, Ph.D., both of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, and their colleagues assessed associations between treatment changes and disability among more than 1,500 triptan users from the longitudinal, population-based AMPP (American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention) study, reporting their findings at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

In one analysis, patients switching to NSAIDs or to combination analgesics containing an opioid or a barbiturate had respective 31% and 48% worsening in scores for headache-related disability, compared with nonswitchers, but patients staying on the triptan or switching to another one did not have any significant change in score. In stratified analyses, switching to an NSAID was associated with a worsening among the subset of patients having the most frequent attacks.

The second study found that adding an NSAID to the triptan improved scores for patients with medium-frequency episodic migraines, while adding an NSAID or another triptan worsened scores for those with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines. Patients with low-frequency episodic migraines did not have any change regardless of the medication added.

"On average, the changes clinicians make in prescription drug therapy in the real world, switching from one triptan to another or adding a second triptan, are not helpful," Dr. Lipton commented. "That is not to say that when we switch individual patients, there isn’t a benefit to that or that optimized algorithms for choosing treatments have no effect on patient care. But it is to say that maybe when we think about what to do with patients who don’t respond to medications, it’s worth considering that switching triptans on average doesn’t have the benefits for disability that I certainly previously thought."

The studies may have had the bias of confounding by indication, whereby the reasons for medication changes (which were unknown) influenced outcomes, he acknowledged. "But they do have the strength of generalizability and reflecting what actually goes on in the real world."

Session attendee Dr. James Couch of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, expressed concern about the possible confounding.

"Most of us have found that all the triptans are not equal, and if you go through the whole list of seven, it’s not unlikely that you will find one that works better than others and so on," he elaborated. Thus, some patients on one triptan "may have gotten a moderate effect, and they were still looking for a triptan that was going to have that whiz-bang effect." Also, insurance company requirements may dictate medication switches in some cases.

Dr. Peter Goadsby of the University of California, San Francisco, asked whether analyses were masking the heterogeneity of response in the study sample. "It strikes me that in practice, it’s quite heterogeneous: You make a change in some patients, they do spectacularly well, or maybe it’s just luck, and other patients don’t," he commented. "So is there more than one population, and are you losing some granularity in what we do by having them all lumped together?"

"Our reason for stratifying by attack frequency was to try to reduce that heterogeneity," Dr. Lipton replied. "And when we stratify by attack frequency, we see some pretty robust effects."

Finally, session co-moderator Dr. Andrew Hershey of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital wondered if the directionality of association was perhaps reversed, and headache-related disability had instead prompted the medication changes.

Dr. Lipton noted that the investigators assessed changes in score from before to after a medication switch, in addition to using stratification. "So that’s our attempt to take baseline differences into account, though it’s certainly imperfect," he acknowledged.

Switching Medications

Dr. Buse and her colleagues studied the impact of medication switches from one year to the next in 799 patients with migraine taking triptans for acute treatment.

"Providers commonly switch patients in their acute pharmacologic regimens, we know that. We switch medications for a variety of reasons: patient preference, nonresponse, what is allowed by third-party payers," she commented. However, most studies of switching medications have looked at short-term outcomes, and few have looked at switches to or from triptans.

Fully 83% of the patients studied continued on the same triptan, 10% switched to another triptan, 4% switched to a combination analgesic containing an opioid or barbiturate, and 3% switched to an NSAID.

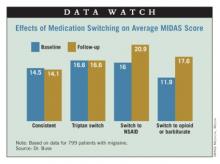

Results showed that headache-related disability, assessed from Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) scores, was essentially unchanged from one year to the next in patients who stayed on the same triptan (14.5 vs. 14.1) or who switched from one triptan to another (16.6 vs. 16.6). In contrast, scores increased (worsened) in patients who switched to NSAIDs (16.0 vs. 20.9) and who switched to combination therapy containing opioids or barbiturates (11.9 vs. 17.6).

Additional analyses showed that the impact of switching to NSAIDs varied according to migraine frequency. Specifically, patients with high-frequency episodic migraines (10-14 headache-days monthly) or chronic migraines (15 or more headache-days monthly) had a significant increase in MIDAS scores when switching to NSAIDs relative to their counterparts with low-frequency episodic migraines (0-4 headache-days monthly) or moderate-frequency episodic migraines (5-9 headache-days monthly).

"Not only did the treatment matter, but the average number of days of headache at baseline matters quite importantly here," Dr. Buse commented.

"In this observational study, switching triptan regimens or switching from a triptan to an alternative pharmacologic therapy for acute migraine does not appear to be associated with improvements in headache-related disability and, in some cases, is associated with increased headache-related disability over the course of 1 year to the second year," she concluded.

Adding medications

Dr. Lipton’s team studied the impact of medication additions from one year to the next in 960 patients with migraine taking triptans for acute treatment.

"Most people with migraine in the population use more than one acute treatment, and triptan users often use more than one triptan or use a triptan in combination with other medications, or even use combination products, such as Treximet [sumatriptan and naproxen], which contains a triptan and a nonsteroidal [anti-inflammatory drug]," he noted.

"By and large, we have not done much in terms of studying combination acute treatment in migraine, and certainly combining triptans has not been studied very often," he noted.

Most patients, 68%, did not change their acute treatment, while 13% added a combination analgesic containing opioids or barbiturates, 12% added another triptan, and 7% added an NSAID.

Results showed that among patients having low-frequency episodic migraines, adding another medication to their triptan did not significantly affect MIDAS score from one year to the next, regardless of the type of medication added.

Among patients with medium-frequency episodic migraines, adding an NSAID was associated with a significant decrease in MIDAS scores, whereas adding other medications did not affect scores.

But among patients with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines, MIDAS scores actually increased significantly with addition of an NSAID or another triptan. They were unaffected by addition of a combination analgesic containing opioids or barbiturates.

Further analyses confirmed that the impact of adding NSAIDs varied according to migraine frequency: Patients with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines had a significant increase in MIDAS scores when switching to NSAIDs relative to their counterparts with low-frequency episodic migraines.

"This is analogous to the finding in the Bigal paper [Headache 2008;48:1157-68] showing that NSAIDs are associated with an increased risk of transition to chronic migraine in people who have high-frequency episodic migraine," Dr. Lipton commented.

Dr. Lipton disclosed that he receives research grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund, and serves as a consultant or advisor to or has received honoraria from the American Headache Society and various pharmaceutical companies manufacturing drugs for migraine. Dr. Buse disclosed that she has received grant support and honoraria from Endo Pharmaceuticals and other pharmaceutical companies manufacturing drugs for migraine. The AMPP study is funded through a research grant to the National Headache Foundation from Ortho-McNeil Neurologics; additional analyses and manuscript preparation were supported through a grant from MAP Pharmaceuticals and Allergan to the National Headache Foundation.

LOS ANGELES – In patients using triptans for the acute treatment of migraine, the impact on headache-related disability of switching or adding medications depends on the frequency of attacks and the type of medication, new data show.

Dr. Richard B. Lipton and Dawn C. Buse, Ph.D., both of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, and their colleagues assessed associations between treatment changes and disability among more than 1,500 triptan users from the longitudinal, population-based AMPP (American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention) study, reporting their findings at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

In one analysis, patients switching to NSAIDs or to combination analgesics containing an opioid or a barbiturate had respective 31% and 48% worsening in scores for headache-related disability, compared with nonswitchers, but patients staying on the triptan or switching to another one did not have any significant change in score. In stratified analyses, switching to an NSAID was associated with a worsening among the subset of patients having the most frequent attacks.

The second study found that adding an NSAID to the triptan improved scores for patients with medium-frequency episodic migraines, while adding an NSAID or another triptan worsened scores for those with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines. Patients with low-frequency episodic migraines did not have any change regardless of the medication added.

"On average, the changes clinicians make in prescription drug therapy in the real world, switching from one triptan to another or adding a second triptan, are not helpful," Dr. Lipton commented. "That is not to say that when we switch individual patients, there isn’t a benefit to that or that optimized algorithms for choosing treatments have no effect on patient care. But it is to say that maybe when we think about what to do with patients who don’t respond to medications, it’s worth considering that switching triptans on average doesn’t have the benefits for disability that I certainly previously thought."

The studies may have had the bias of confounding by indication, whereby the reasons for medication changes (which were unknown) influenced outcomes, he acknowledged. "But they do have the strength of generalizability and reflecting what actually goes on in the real world."

Session attendee Dr. James Couch of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, expressed concern about the possible confounding.

"Most of us have found that all the triptans are not equal, and if you go through the whole list of seven, it’s not unlikely that you will find one that works better than others and so on," he elaborated. Thus, some patients on one triptan "may have gotten a moderate effect, and they were still looking for a triptan that was going to have that whiz-bang effect." Also, insurance company requirements may dictate medication switches in some cases.

Dr. Peter Goadsby of the University of California, San Francisco, asked whether analyses were masking the heterogeneity of response in the study sample. "It strikes me that in practice, it’s quite heterogeneous: You make a change in some patients, they do spectacularly well, or maybe it’s just luck, and other patients don’t," he commented. "So is there more than one population, and are you losing some granularity in what we do by having them all lumped together?"

"Our reason for stratifying by attack frequency was to try to reduce that heterogeneity," Dr. Lipton replied. "And when we stratify by attack frequency, we see some pretty robust effects."

Finally, session co-moderator Dr. Andrew Hershey of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital wondered if the directionality of association was perhaps reversed, and headache-related disability had instead prompted the medication changes.

Dr. Lipton noted that the investigators assessed changes in score from before to after a medication switch, in addition to using stratification. "So that’s our attempt to take baseline differences into account, though it’s certainly imperfect," he acknowledged.

Switching Medications

Dr. Buse and her colleagues studied the impact of medication switches from one year to the next in 799 patients with migraine taking triptans for acute treatment.

"Providers commonly switch patients in their acute pharmacologic regimens, we know that. We switch medications for a variety of reasons: patient preference, nonresponse, what is allowed by third-party payers," she commented. However, most studies of switching medications have looked at short-term outcomes, and few have looked at switches to or from triptans.

Fully 83% of the patients studied continued on the same triptan, 10% switched to another triptan, 4% switched to a combination analgesic containing an opioid or barbiturate, and 3% switched to an NSAID.

Results showed that headache-related disability, assessed from Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) scores, was essentially unchanged from one year to the next in patients who stayed on the same triptan (14.5 vs. 14.1) or who switched from one triptan to another (16.6 vs. 16.6). In contrast, scores increased (worsened) in patients who switched to NSAIDs (16.0 vs. 20.9) and who switched to combination therapy containing opioids or barbiturates (11.9 vs. 17.6).

Additional analyses showed that the impact of switching to NSAIDs varied according to migraine frequency. Specifically, patients with high-frequency episodic migraines (10-14 headache-days monthly) or chronic migraines (15 or more headache-days monthly) had a significant increase in MIDAS scores when switching to NSAIDs relative to their counterparts with low-frequency episodic migraines (0-4 headache-days monthly) or moderate-frequency episodic migraines (5-9 headache-days monthly).

"Not only did the treatment matter, but the average number of days of headache at baseline matters quite importantly here," Dr. Buse commented.

"In this observational study, switching triptan regimens or switching from a triptan to an alternative pharmacologic therapy for acute migraine does not appear to be associated with improvements in headache-related disability and, in some cases, is associated with increased headache-related disability over the course of 1 year to the second year," she concluded.

Adding medications

Dr. Lipton’s team studied the impact of medication additions from one year to the next in 960 patients with migraine taking triptans for acute treatment.

"Most people with migraine in the population use more than one acute treatment, and triptan users often use more than one triptan or use a triptan in combination with other medications, or even use combination products, such as Treximet [sumatriptan and naproxen], which contains a triptan and a nonsteroidal [anti-inflammatory drug]," he noted.

"By and large, we have not done much in terms of studying combination acute treatment in migraine, and certainly combining triptans has not been studied very often," he noted.

Most patients, 68%, did not change their acute treatment, while 13% added a combination analgesic containing opioids or barbiturates, 12% added another triptan, and 7% added an NSAID.

Results showed that among patients having low-frequency episodic migraines, adding another medication to their triptan did not significantly affect MIDAS score from one year to the next, regardless of the type of medication added.

Among patients with medium-frequency episodic migraines, adding an NSAID was associated with a significant decrease in MIDAS scores, whereas adding other medications did not affect scores.

But among patients with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines, MIDAS scores actually increased significantly with addition of an NSAID or another triptan. They were unaffected by addition of a combination analgesic containing opioids or barbiturates.

Further analyses confirmed that the impact of adding NSAIDs varied according to migraine frequency: Patients with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines had a significant increase in MIDAS scores when switching to NSAIDs relative to their counterparts with low-frequency episodic migraines.

"This is analogous to the finding in the Bigal paper [Headache 2008;48:1157-68] showing that NSAIDs are associated with an increased risk of transition to chronic migraine in people who have high-frequency episodic migraine," Dr. Lipton commented.

Dr. Lipton disclosed that he receives research grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund, and serves as a consultant or advisor to or has received honoraria from the American Headache Society and various pharmaceutical companies manufacturing drugs for migraine. Dr. Buse disclosed that she has received grant support and honoraria from Endo Pharmaceuticals and other pharmaceutical companies manufacturing drugs for migraine. The AMPP study is funded through a research grant to the National Headache Foundation from Ortho-McNeil Neurologics; additional analyses and manuscript preparation were supported through a grant from MAP Pharmaceuticals and Allergan to the National Headache Foundation.

LOS ANGELES – In patients using triptans for the acute treatment of migraine, the impact on headache-related disability of switching or adding medications depends on the frequency of attacks and the type of medication, new data show.

Dr. Richard B. Lipton and Dawn C. Buse, Ph.D., both of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, and their colleagues assessed associations between treatment changes and disability among more than 1,500 triptan users from the longitudinal, population-based AMPP (American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention) study, reporting their findings at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

In one analysis, patients switching to NSAIDs or to combination analgesics containing an opioid or a barbiturate had respective 31% and 48% worsening in scores for headache-related disability, compared with nonswitchers, but patients staying on the triptan or switching to another one did not have any significant change in score. In stratified analyses, switching to an NSAID was associated with a worsening among the subset of patients having the most frequent attacks.

The second study found that adding an NSAID to the triptan improved scores for patients with medium-frequency episodic migraines, while adding an NSAID or another triptan worsened scores for those with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines. Patients with low-frequency episodic migraines did not have any change regardless of the medication added.

"On average, the changes clinicians make in prescription drug therapy in the real world, switching from one triptan to another or adding a second triptan, are not helpful," Dr. Lipton commented. "That is not to say that when we switch individual patients, there isn’t a benefit to that or that optimized algorithms for choosing treatments have no effect on patient care. But it is to say that maybe when we think about what to do with patients who don’t respond to medications, it’s worth considering that switching triptans on average doesn’t have the benefits for disability that I certainly previously thought."

The studies may have had the bias of confounding by indication, whereby the reasons for medication changes (which were unknown) influenced outcomes, he acknowledged. "But they do have the strength of generalizability and reflecting what actually goes on in the real world."

Session attendee Dr. James Couch of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, expressed concern about the possible confounding.

"Most of us have found that all the triptans are not equal, and if you go through the whole list of seven, it’s not unlikely that you will find one that works better than others and so on," he elaborated. Thus, some patients on one triptan "may have gotten a moderate effect, and they were still looking for a triptan that was going to have that whiz-bang effect." Also, insurance company requirements may dictate medication switches in some cases.

Dr. Peter Goadsby of the University of California, San Francisco, asked whether analyses were masking the heterogeneity of response in the study sample. "It strikes me that in practice, it’s quite heterogeneous: You make a change in some patients, they do spectacularly well, or maybe it’s just luck, and other patients don’t," he commented. "So is there more than one population, and are you losing some granularity in what we do by having them all lumped together?"

"Our reason for stratifying by attack frequency was to try to reduce that heterogeneity," Dr. Lipton replied. "And when we stratify by attack frequency, we see some pretty robust effects."

Finally, session co-moderator Dr. Andrew Hershey of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital wondered if the directionality of association was perhaps reversed, and headache-related disability had instead prompted the medication changes.

Dr. Lipton noted that the investigators assessed changes in score from before to after a medication switch, in addition to using stratification. "So that’s our attempt to take baseline differences into account, though it’s certainly imperfect," he acknowledged.

Switching Medications

Dr. Buse and her colleagues studied the impact of medication switches from one year to the next in 799 patients with migraine taking triptans for acute treatment.

"Providers commonly switch patients in their acute pharmacologic regimens, we know that. We switch medications for a variety of reasons: patient preference, nonresponse, what is allowed by third-party payers," she commented. However, most studies of switching medications have looked at short-term outcomes, and few have looked at switches to or from triptans.

Fully 83% of the patients studied continued on the same triptan, 10% switched to another triptan, 4% switched to a combination analgesic containing an opioid or barbiturate, and 3% switched to an NSAID.

Results showed that headache-related disability, assessed from Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) scores, was essentially unchanged from one year to the next in patients who stayed on the same triptan (14.5 vs. 14.1) or who switched from one triptan to another (16.6 vs. 16.6). In contrast, scores increased (worsened) in patients who switched to NSAIDs (16.0 vs. 20.9) and who switched to combination therapy containing opioids or barbiturates (11.9 vs. 17.6).

Additional analyses showed that the impact of switching to NSAIDs varied according to migraine frequency. Specifically, patients with high-frequency episodic migraines (10-14 headache-days monthly) or chronic migraines (15 or more headache-days monthly) had a significant increase in MIDAS scores when switching to NSAIDs relative to their counterparts with low-frequency episodic migraines (0-4 headache-days monthly) or moderate-frequency episodic migraines (5-9 headache-days monthly).

"Not only did the treatment matter, but the average number of days of headache at baseline matters quite importantly here," Dr. Buse commented.

"In this observational study, switching triptan regimens or switching from a triptan to an alternative pharmacologic therapy for acute migraine does not appear to be associated with improvements in headache-related disability and, in some cases, is associated with increased headache-related disability over the course of 1 year to the second year," she concluded.

Adding medications

Dr. Lipton’s team studied the impact of medication additions from one year to the next in 960 patients with migraine taking triptans for acute treatment.

"Most people with migraine in the population use more than one acute treatment, and triptan users often use more than one triptan or use a triptan in combination with other medications, or even use combination products, such as Treximet [sumatriptan and naproxen], which contains a triptan and a nonsteroidal [anti-inflammatory drug]," he noted.

"By and large, we have not done much in terms of studying combination acute treatment in migraine, and certainly combining triptans has not been studied very often," he noted.

Most patients, 68%, did not change their acute treatment, while 13% added a combination analgesic containing opioids or barbiturates, 12% added another triptan, and 7% added an NSAID.

Results showed that among patients having low-frequency episodic migraines, adding another medication to their triptan did not significantly affect MIDAS score from one year to the next, regardless of the type of medication added.

Among patients with medium-frequency episodic migraines, adding an NSAID was associated with a significant decrease in MIDAS scores, whereas adding other medications did not affect scores.

But among patients with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines, MIDAS scores actually increased significantly with addition of an NSAID or another triptan. They were unaffected by addition of a combination analgesic containing opioids or barbiturates.

Further analyses confirmed that the impact of adding NSAIDs varied according to migraine frequency: Patients with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines had a significant increase in MIDAS scores when switching to NSAIDs relative to their counterparts with low-frequency episodic migraines.

"This is analogous to the finding in the Bigal paper [Headache 2008;48:1157-68] showing that NSAIDs are associated with an increased risk of transition to chronic migraine in people who have high-frequency episodic migraine," Dr. Lipton commented.

Dr. Lipton disclosed that he receives research grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund, and serves as a consultant or advisor to or has received honoraria from the American Headache Society and various pharmaceutical companies manufacturing drugs for migraine. Dr. Buse disclosed that she has received grant support and honoraria from Endo Pharmaceuticals and other pharmaceutical companies manufacturing drugs for migraine. The AMPP study is funded through a research grant to the National Headache Foundation from Ortho-McNeil Neurologics; additional analyses and manuscript preparation were supported through a grant from MAP Pharmaceuticals and Allergan to the National Headache Foundation.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN HEADACHE SOCIETY

Major Finding: Headache-related disability among patients taking a triptan worsened by 31% in patients who switched to an NSAID and was worst among those with high-frequency episodic migraines or chronic migraines. Adding an NSAID benefited only medium-frequency patients and worsened high-frequency patients.

Data Source: A pair of studies in 799 and 960 triptan users with migraine from the longitudinal, population-based American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study

Disclosures: Dr. Lipton disclosed that he receives research grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund, and serves as a consultant or advisor to or has received honoraria from the American Headache Society and various pharmaceutical companies manufacturing drugs for migraine. Dr. Buse disclosed that she has received grant support and honoraria from Endo Pharmaceuticals and other pharmaceutical companies manufacturing drugs for migraine. The AMPP study is funded through a research grant to the National Headache Foundation from Ortho-McNeil Neurologics; additional analyses and manuscript preparation were supported through a grant from MAP Pharmaceuticals and Allergan to the National Headache Foundation.