User login

The common practice of immediate cord clamping, which generally means clamping within 15-20 seconds after birth, was fueled by efforts to reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, a leading cause of maternal death worldwide. Immediate clamping was part of a full active management intervention recommended in 2007 by the World Health Organization, along with the use of uterotonics (generally oxytocin) immediately after birth and controlled cord traction to quickly deliver the placenta.

Adoption of the WHO-recommended “active management during the third stage of labor” (AMTSL) worked, leading to a 70% reduction in postpartum hemorrhage and a 60% reduction in blood transfusion over passive management. However, it appears that immediate cord clamping has not played an important role in these reductions. Several randomized controlled trials have shown that early clamping does not impact the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (> 1000 cc or > 500 cc), nor does it impact the need for manual removal of the placenta or the need for blood transfusion.

Instead, the critical component of the AMTSL package appears to be administration of a uterotonic, as reported in a large WHO-directed multicenter clinical trial published in 2012. The study also found that women who received controlled cord traction bled an average of 11 cc less – an insignificant difference – than did women who delivered their placentas by their own effort. Moreover, they had a third stage of labor that was an average of 6 minutes shorter (Lancet 2012;379:1721-7).

With assurance that the timing of umbilical cord clamping does not impact maternal outcomes, investigators have begun to look more at the impact of immediate versus delayed cord clamping on the health of the baby.

Thus far, the issues in this arena are a bit more complicated than on the maternal side. There are indications, however, that slight delays in umbilical cord clamping may be beneficial for the newborn – particularly for preterm infants, who appear in systemic reviews to have a nearly 50% reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage when clamping is delayed.

Timing in term infants

The theoretical benefits of delayed cord clamping include increased neonatal blood volume (improved perfusion and decreased organ injury), more time for spontaneous breathing (reduced risks of resuscitation and a smoother transition of cardiopulmonary and cerebral circulation), and increased stem cells for the infant (anti-inflammatory, neurotropic, and neuroprotective effects).

Theoretically, delayed clamping will increase the infant’s iron stores and lower the incidence of iron deficiency anemia during infancy. This is particularly relevant in developing countries, where up to 50% of infants have anemia by 1 year of age. Anemia is consistently associated with abnormal neurodevelopment, and treatment may not always reverse developmental issues.

On the negative side, delayed clamping is associated with theoretical concerns about hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice, hypothermia, polycythemia, and delays in the bonding of infants and mothers.

For term infants, our best reading on the benefits and risks of delayed umbilical cord clamping comes from a 2013 Cochrane systematic review that assessed results from 15 randomized controlled trials involving 3,911 women and infant pairs. Early cord clamping was generally carried out within 60 seconds of birth, whereas delayed cord clamping involved clamping the umbilical cord more than 1 minute after birth or when cord pulsation has ceased.

The review found that delayed clamping was associated with a significantly higher neonatal hemoglobin concentration at 24-48 hours postpartum (a weighted mean difference of 2 g/dL) and increased iron reserves up to 6 months after birth. Infants in the early clamping group were more than twice as likely to be iron deficient at 3-6 months compared with infants whose cord clamping was delayed (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;7:CD004074)

There were no significant differences between early and late clamping in neonatal mortality or for most other neonatal morbidity outcomes. Delayed clamping also did not increase the risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage, blood loss, or reduced hemoglobin levels in mothers.

The downside to delayed cord clamping was an increased risk of jaundice requiring phototherapy. Infants in the later cord clamping group were 40% more likely to need phototherapy – a difference that equates to 3% of infants in the early clamping group and 5% of infants in the late clamping group.

Data were insufficient in the Cochrane review to draw reliable conclusions about the comparative effects on other short-term outcomes such as symptomatic polycythemia, respiratory problems, hypothermia, and infection, as data were limited on long-term outcomes.

In practice, this means that the risk of jaundice must be weighed against the risk of iron deficiency. In developed countries we have the resources both to increase iron stores of infants and to provide phototherapy. While the WHO recommends umbilical cord clamping after 1-3 minutes to improve an infant’s iron status, I do not believe the evidence is strong enough to universally adopt such delayed cord clamping in the United States.

Considering the risks of jaundice and the relative infrequency of iron deficiency in the United States, we should not routinely delay clamping for term infants at this point.

A recent committee opinion developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (No. 543, December 2012) captures this view by concluding that “insufficient evidence exists to support or to refute the benefits from delayed umbilical cord clamping for term infants that are born in settings with rich resources.” Although the ACOG opinion preceded the Cochrane review, the committee, of which I was a member, reviewed much of the same literature.

Timing in preterm infants

Preterm neonates are at increased risk of temperature dysregulation, hypotension, and the need for rapid initial pediatric care and blood transfusion. The increased risk of intraventricular hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants is possibly related to the increased risk of hypotension.

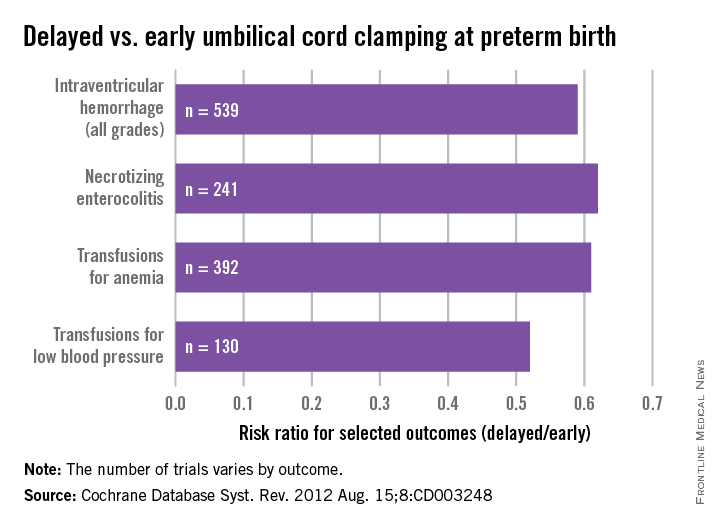

As with term infants, a 2012 Cochrane systematic review offers good insight on our current knowledge. This review of umbilical cord clamping at preterm birth covers 15 studies that included 738 infants delivered between 24 and 36 weeks of gestation. The timing of umbilical cord clamping ranged from 25 seconds to a maximum of 180 seconds (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;8:CD003248).

Delayed cord clamping was associated with fewer transfusions for anemia or low blood pressure, less intraventricular hemorrhage of all grades (relative risk 0.59), and a lower risk for necrotizing enterocolitis (relative risk 0.62), compared with immediate clamping.

While there were no clear differences with respect to severe intraventricular hemorrhage (grades 3-4), the nearly 50% reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage overall among deliveries with delayed clamping was significant enough to prompt ACOG to conclude that delayed cord clamping should be considered for preterm infants. This reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage appears to be the single most important benefit, based on current findings.

The data on cord clamping in preterm infants are suggestive of benefit, but are not robust. The studies published thus far have been small, and many of them, as the 2012 Cochrane review points out, involved incomplete reporting and wide confidence intervals. Moreover, just as with the studies on term infants, there has been a lack of long-term follow-up in most of the published trials.

When considering delayed cord clamping in preterm infants, as the ACOG Committee Opinion recommends, I urge focusing on earlier gestational ages. Allowing more placental transfusion at births that occur at or after 36 weeks of gestation may not make much sense because by that point the risk of intraventricular hemorrhage is almost nonexistent.

Our practice and the future

At our institution, births that occur at less than 32 weeks of gestation are eligible for delayed umbilical cord clamping, usually at 30-45 seconds after birth. The main contraindications are placental abruption and multiples.

We do not perform any milking or stripping of the umbilical cord, as the risks are unknown and it is not yet clear whether such practices are equivalent to delayed cord clamping. Compared with delayed cord clamping, which is a natural passive transfusion of placental blood to the infant, milking and stripping are not physiologic.

Additional data from an ongoing large international multicenter study, the Australian Placental Transfusion Study, may resolve some of the current controversy. This study is evaluating the cord clamping in neonates < 30 weeks’ gestation. Another study ongoing in Europe should also provide more information.

These studies – and other trials that are larger and longer than the trials published thus far – are necessary to evaluate long-term outcomes and to establish the ideal timing for umbilical cord clamping. Research is also needed to evaluate the management of the third stage of labor relative to umbilical cord clamping as well as the timing in relation to the initiation of voluntary or assisted ventilation.

Dr. Macones said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Macones is the Mitchell and Elaine Yanow Professor and Chair, and director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine and ultrasound in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University, St. Louis.

The common practice of immediate cord clamping, which generally means clamping within 15-20 seconds after birth, was fueled by efforts to reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, a leading cause of maternal death worldwide. Immediate clamping was part of a full active management intervention recommended in 2007 by the World Health Organization, along with the use of uterotonics (generally oxytocin) immediately after birth and controlled cord traction to quickly deliver the placenta.

Adoption of the WHO-recommended “active management during the third stage of labor” (AMTSL) worked, leading to a 70% reduction in postpartum hemorrhage and a 60% reduction in blood transfusion over passive management. However, it appears that immediate cord clamping has not played an important role in these reductions. Several randomized controlled trials have shown that early clamping does not impact the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (> 1000 cc or > 500 cc), nor does it impact the need for manual removal of the placenta or the need for blood transfusion.

Instead, the critical component of the AMTSL package appears to be administration of a uterotonic, as reported in a large WHO-directed multicenter clinical trial published in 2012. The study also found that women who received controlled cord traction bled an average of 11 cc less – an insignificant difference – than did women who delivered their placentas by their own effort. Moreover, they had a third stage of labor that was an average of 6 minutes shorter (Lancet 2012;379:1721-7).

With assurance that the timing of umbilical cord clamping does not impact maternal outcomes, investigators have begun to look more at the impact of immediate versus delayed cord clamping on the health of the baby.

Thus far, the issues in this arena are a bit more complicated than on the maternal side. There are indications, however, that slight delays in umbilical cord clamping may be beneficial for the newborn – particularly for preterm infants, who appear in systemic reviews to have a nearly 50% reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage when clamping is delayed.

Timing in term infants

The theoretical benefits of delayed cord clamping include increased neonatal blood volume (improved perfusion and decreased organ injury), more time for spontaneous breathing (reduced risks of resuscitation and a smoother transition of cardiopulmonary and cerebral circulation), and increased stem cells for the infant (anti-inflammatory, neurotropic, and neuroprotective effects).

Theoretically, delayed clamping will increase the infant’s iron stores and lower the incidence of iron deficiency anemia during infancy. This is particularly relevant in developing countries, where up to 50% of infants have anemia by 1 year of age. Anemia is consistently associated with abnormal neurodevelopment, and treatment may not always reverse developmental issues.

On the negative side, delayed clamping is associated with theoretical concerns about hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice, hypothermia, polycythemia, and delays in the bonding of infants and mothers.

For term infants, our best reading on the benefits and risks of delayed umbilical cord clamping comes from a 2013 Cochrane systematic review that assessed results from 15 randomized controlled trials involving 3,911 women and infant pairs. Early cord clamping was generally carried out within 60 seconds of birth, whereas delayed cord clamping involved clamping the umbilical cord more than 1 minute after birth or when cord pulsation has ceased.

The review found that delayed clamping was associated with a significantly higher neonatal hemoglobin concentration at 24-48 hours postpartum (a weighted mean difference of 2 g/dL) and increased iron reserves up to 6 months after birth. Infants in the early clamping group were more than twice as likely to be iron deficient at 3-6 months compared with infants whose cord clamping was delayed (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;7:CD004074)

There were no significant differences between early and late clamping in neonatal mortality or for most other neonatal morbidity outcomes. Delayed clamping also did not increase the risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage, blood loss, or reduced hemoglobin levels in mothers.

The downside to delayed cord clamping was an increased risk of jaundice requiring phototherapy. Infants in the later cord clamping group were 40% more likely to need phototherapy – a difference that equates to 3% of infants in the early clamping group and 5% of infants in the late clamping group.

Data were insufficient in the Cochrane review to draw reliable conclusions about the comparative effects on other short-term outcomes such as symptomatic polycythemia, respiratory problems, hypothermia, and infection, as data were limited on long-term outcomes.

In practice, this means that the risk of jaundice must be weighed against the risk of iron deficiency. In developed countries we have the resources both to increase iron stores of infants and to provide phototherapy. While the WHO recommends umbilical cord clamping after 1-3 minutes to improve an infant’s iron status, I do not believe the evidence is strong enough to universally adopt such delayed cord clamping in the United States.

Considering the risks of jaundice and the relative infrequency of iron deficiency in the United States, we should not routinely delay clamping for term infants at this point.

A recent committee opinion developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (No. 543, December 2012) captures this view by concluding that “insufficient evidence exists to support or to refute the benefits from delayed umbilical cord clamping for term infants that are born in settings with rich resources.” Although the ACOG opinion preceded the Cochrane review, the committee, of which I was a member, reviewed much of the same literature.

Timing in preterm infants

Preterm neonates are at increased risk of temperature dysregulation, hypotension, and the need for rapid initial pediatric care and blood transfusion. The increased risk of intraventricular hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants is possibly related to the increased risk of hypotension.

As with term infants, a 2012 Cochrane systematic review offers good insight on our current knowledge. This review of umbilical cord clamping at preterm birth covers 15 studies that included 738 infants delivered between 24 and 36 weeks of gestation. The timing of umbilical cord clamping ranged from 25 seconds to a maximum of 180 seconds (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;8:CD003248).

Delayed cord clamping was associated with fewer transfusions for anemia or low blood pressure, less intraventricular hemorrhage of all grades (relative risk 0.59), and a lower risk for necrotizing enterocolitis (relative risk 0.62), compared with immediate clamping.

While there were no clear differences with respect to severe intraventricular hemorrhage (grades 3-4), the nearly 50% reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage overall among deliveries with delayed clamping was significant enough to prompt ACOG to conclude that delayed cord clamping should be considered for preterm infants. This reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage appears to be the single most important benefit, based on current findings.

The data on cord clamping in preterm infants are suggestive of benefit, but are not robust. The studies published thus far have been small, and many of them, as the 2012 Cochrane review points out, involved incomplete reporting and wide confidence intervals. Moreover, just as with the studies on term infants, there has been a lack of long-term follow-up in most of the published trials.

When considering delayed cord clamping in preterm infants, as the ACOG Committee Opinion recommends, I urge focusing on earlier gestational ages. Allowing more placental transfusion at births that occur at or after 36 weeks of gestation may not make much sense because by that point the risk of intraventricular hemorrhage is almost nonexistent.

Our practice and the future

At our institution, births that occur at less than 32 weeks of gestation are eligible for delayed umbilical cord clamping, usually at 30-45 seconds after birth. The main contraindications are placental abruption and multiples.

We do not perform any milking or stripping of the umbilical cord, as the risks are unknown and it is not yet clear whether such practices are equivalent to delayed cord clamping. Compared with delayed cord clamping, which is a natural passive transfusion of placental blood to the infant, milking and stripping are not physiologic.

Additional data from an ongoing large international multicenter study, the Australian Placental Transfusion Study, may resolve some of the current controversy. This study is evaluating the cord clamping in neonates < 30 weeks’ gestation. Another study ongoing in Europe should also provide more information.

These studies – and other trials that are larger and longer than the trials published thus far – are necessary to evaluate long-term outcomes and to establish the ideal timing for umbilical cord clamping. Research is also needed to evaluate the management of the third stage of labor relative to umbilical cord clamping as well as the timing in relation to the initiation of voluntary or assisted ventilation.

Dr. Macones said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Macones is the Mitchell and Elaine Yanow Professor and Chair, and director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine and ultrasound in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University, St. Louis.

The common practice of immediate cord clamping, which generally means clamping within 15-20 seconds after birth, was fueled by efforts to reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, a leading cause of maternal death worldwide. Immediate clamping was part of a full active management intervention recommended in 2007 by the World Health Organization, along with the use of uterotonics (generally oxytocin) immediately after birth and controlled cord traction to quickly deliver the placenta.

Adoption of the WHO-recommended “active management during the third stage of labor” (AMTSL) worked, leading to a 70% reduction in postpartum hemorrhage and a 60% reduction in blood transfusion over passive management. However, it appears that immediate cord clamping has not played an important role in these reductions. Several randomized controlled trials have shown that early clamping does not impact the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (> 1000 cc or > 500 cc), nor does it impact the need for manual removal of the placenta or the need for blood transfusion.

Instead, the critical component of the AMTSL package appears to be administration of a uterotonic, as reported in a large WHO-directed multicenter clinical trial published in 2012. The study also found that women who received controlled cord traction bled an average of 11 cc less – an insignificant difference – than did women who delivered their placentas by their own effort. Moreover, they had a third stage of labor that was an average of 6 minutes shorter (Lancet 2012;379:1721-7).

With assurance that the timing of umbilical cord clamping does not impact maternal outcomes, investigators have begun to look more at the impact of immediate versus delayed cord clamping on the health of the baby.

Thus far, the issues in this arena are a bit more complicated than on the maternal side. There are indications, however, that slight delays in umbilical cord clamping may be beneficial for the newborn – particularly for preterm infants, who appear in systemic reviews to have a nearly 50% reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage when clamping is delayed.

Timing in term infants

The theoretical benefits of delayed cord clamping include increased neonatal blood volume (improved perfusion and decreased organ injury), more time for spontaneous breathing (reduced risks of resuscitation and a smoother transition of cardiopulmonary and cerebral circulation), and increased stem cells for the infant (anti-inflammatory, neurotropic, and neuroprotective effects).

Theoretically, delayed clamping will increase the infant’s iron stores and lower the incidence of iron deficiency anemia during infancy. This is particularly relevant in developing countries, where up to 50% of infants have anemia by 1 year of age. Anemia is consistently associated with abnormal neurodevelopment, and treatment may not always reverse developmental issues.

On the negative side, delayed clamping is associated with theoretical concerns about hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice, hypothermia, polycythemia, and delays in the bonding of infants and mothers.

For term infants, our best reading on the benefits and risks of delayed umbilical cord clamping comes from a 2013 Cochrane systematic review that assessed results from 15 randomized controlled trials involving 3,911 women and infant pairs. Early cord clamping was generally carried out within 60 seconds of birth, whereas delayed cord clamping involved clamping the umbilical cord more than 1 minute after birth or when cord pulsation has ceased.

The review found that delayed clamping was associated with a significantly higher neonatal hemoglobin concentration at 24-48 hours postpartum (a weighted mean difference of 2 g/dL) and increased iron reserves up to 6 months after birth. Infants in the early clamping group were more than twice as likely to be iron deficient at 3-6 months compared with infants whose cord clamping was delayed (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;7:CD004074)

There were no significant differences between early and late clamping in neonatal mortality or for most other neonatal morbidity outcomes. Delayed clamping also did not increase the risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage, blood loss, or reduced hemoglobin levels in mothers.

The downside to delayed cord clamping was an increased risk of jaundice requiring phototherapy. Infants in the later cord clamping group were 40% more likely to need phototherapy – a difference that equates to 3% of infants in the early clamping group and 5% of infants in the late clamping group.

Data were insufficient in the Cochrane review to draw reliable conclusions about the comparative effects on other short-term outcomes such as symptomatic polycythemia, respiratory problems, hypothermia, and infection, as data were limited on long-term outcomes.

In practice, this means that the risk of jaundice must be weighed against the risk of iron deficiency. In developed countries we have the resources both to increase iron stores of infants and to provide phototherapy. While the WHO recommends umbilical cord clamping after 1-3 minutes to improve an infant’s iron status, I do not believe the evidence is strong enough to universally adopt such delayed cord clamping in the United States.

Considering the risks of jaundice and the relative infrequency of iron deficiency in the United States, we should not routinely delay clamping for term infants at this point.

A recent committee opinion developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (No. 543, December 2012) captures this view by concluding that “insufficient evidence exists to support or to refute the benefits from delayed umbilical cord clamping for term infants that are born in settings with rich resources.” Although the ACOG opinion preceded the Cochrane review, the committee, of which I was a member, reviewed much of the same literature.

Timing in preterm infants

Preterm neonates are at increased risk of temperature dysregulation, hypotension, and the need for rapid initial pediatric care and blood transfusion. The increased risk of intraventricular hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants is possibly related to the increased risk of hypotension.

As with term infants, a 2012 Cochrane systematic review offers good insight on our current knowledge. This review of umbilical cord clamping at preterm birth covers 15 studies that included 738 infants delivered between 24 and 36 weeks of gestation. The timing of umbilical cord clamping ranged from 25 seconds to a maximum of 180 seconds (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;8:CD003248).

Delayed cord clamping was associated with fewer transfusions for anemia or low blood pressure, less intraventricular hemorrhage of all grades (relative risk 0.59), and a lower risk for necrotizing enterocolitis (relative risk 0.62), compared with immediate clamping.

While there were no clear differences with respect to severe intraventricular hemorrhage (grades 3-4), the nearly 50% reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage overall among deliveries with delayed clamping was significant enough to prompt ACOG to conclude that delayed cord clamping should be considered for preterm infants. This reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage appears to be the single most important benefit, based on current findings.

The data on cord clamping in preterm infants are suggestive of benefit, but are not robust. The studies published thus far have been small, and many of them, as the 2012 Cochrane review points out, involved incomplete reporting and wide confidence intervals. Moreover, just as with the studies on term infants, there has been a lack of long-term follow-up in most of the published trials.

When considering delayed cord clamping in preterm infants, as the ACOG Committee Opinion recommends, I urge focusing on earlier gestational ages. Allowing more placental transfusion at births that occur at or after 36 weeks of gestation may not make much sense because by that point the risk of intraventricular hemorrhage is almost nonexistent.

Our practice and the future

At our institution, births that occur at less than 32 weeks of gestation are eligible for delayed umbilical cord clamping, usually at 30-45 seconds after birth. The main contraindications are placental abruption and multiples.

We do not perform any milking or stripping of the umbilical cord, as the risks are unknown and it is not yet clear whether such practices are equivalent to delayed cord clamping. Compared with delayed cord clamping, which is a natural passive transfusion of placental blood to the infant, milking and stripping are not physiologic.

Additional data from an ongoing large international multicenter study, the Australian Placental Transfusion Study, may resolve some of the current controversy. This study is evaluating the cord clamping in neonates < 30 weeks’ gestation. Another study ongoing in Europe should also provide more information.

These studies – and other trials that are larger and longer than the trials published thus far – are necessary to evaluate long-term outcomes and to establish the ideal timing for umbilical cord clamping. Research is also needed to evaluate the management of the third stage of labor relative to umbilical cord clamping as well as the timing in relation to the initiation of voluntary or assisted ventilation.

Dr. Macones said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Macones is the Mitchell and Elaine Yanow Professor and Chair, and director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine and ultrasound in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University, St. Louis.