User login

Clinicians often use the symptom-triggered Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Scale, Revised (CIWA-Ar)1 to assess patients’ risk for alcohol withdrawal because it has well-documented reliability, reproducibility, and validity based on comparison with ratings by expert clinicians.2,3 The CIWA-Ar commonly is used to determine when to administer lorazepam to limit or prevent morbidity and mortality in patients who are at risk of or are experiencing alcohol withdrawal. Refined to a list of 10 signs and symptoms, the CIWA-Ar is easy to administer and useful in a variety of clinical settings. The maximum score is 67, and patients with a score >15 are at increased risk for severe alcohol withdrawal.1 For a downloadable copy of the CIWA-Ar, click here.

Despite the benefits of using the CIWA-Ar, qualitative description of certain alcohol withdrawal symptoms is prone to subjective misinterpretation and can result in falsely elevated scores, excessive benzodiazepine administration, and associated sequelae.4 This article describes such a scenario, and examines factors that can contribute to a falsely elevated CIWA-Ar score.

CASE REPORT: Resistant alcohol withdrawal

Mr. J, age 24, is referred to the consultation-liaison service at our teaching hospital for “overall psychiatric assessment and help with alcohol withdrawal.” When brought to the hospital, Mr. J was experiencing diaphoresis and tachycardia. During the interview, he says he “experiences withdrawal symptoms all the time, so I am familiar with the signs.”

Mr. J is cooperative with the interview. Psychomotor agitation or retardation is not noted. His speech is goal-directed, his mood is “calm,” and his affect is within normal range. His thought content is devoid of psychoses or lethal ideations. On Mini-Mental State Examination, Mr. J scores 28 out of 30, which indicates normal cognitive functioning. He reports drinking eight 40-oz bottles of beer daily for the past 3 months. He started drinking alcohol at age 14 and has had only one 1-year period of sobriety. He denies using illicit drugs and his urine drug screen is unremarkable. Mr. J has a history of delirium tremens (DTs), no significant medical history, and was not taking any medications when admitted. His psychiatric history includes generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and antisocial personality disorder and his family history is significant for alcohol dependence.

Laboratory workup is unremarkable except for a blood alcohol level of 0.23%. Review of systems is significant for mild tremor but no other symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Physical examination is within normal limits.

Mr. J is started on a symptom-trigger alcohol detoxification protocol using the CIWA-Ar. Based on an elevated CIWA-Ar score of 33, he receives lorazepam IV, 11 mg on his first day of hospitalization and 8 mg on the second day. On the third day, Mr. J is agitated and pulls his IV lines in an attempt to leave. Over the next 24 hours, his blood pressure ranges from 136/90 mm Hg to 169/92 mm Hg and his pulse ranges from 94 to 115 beats per minute. He is given lorazepam, 30 mg, and is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

At this time, Mr. J’s Delirium Rating Scale (DRS) score is 20 (maximum: 32). He remains in the ICU on lorazepam, 25 mg/hr. After 3 days in the ICU, lorazepam is titrated and stopped 2 days later. After lorazepam is stopped, Mr. J’s DRS score is 0, his vital signs are stable, and he no longer demonstrates signs or symptoms of DTs or alcohol withdrawal. He is discharged 1 day later.

Symptom-triggered treatment

Alcohol withdrawal symptoms mainly are caused by the effects of chronic alcohol exposure on brain γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate systems; benzodiazepines are the standard of care (Box).5,6 Mr. J had a history of DTs, which is a risk factor for more severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms and recurrence of DTs.7 Some authors report that fixed dosing intervals are the “gold standard therapy” for alcohol withdrawal, and may be preferable for patients with a history of DTs.8 However, Mr. J was placed on a symptom-triggered protocol, which is standard at our hospital. The decision to implement this protocol was based on concerns of oversedation and possible respiratory suppression. Clinical trials have demonstrated that compared with fixed scheduled therapy for alcohol withdrawal, symptom-triggered protocols result in a reduced need for benzodiazepines (Table).

This treatment strategy requires frequent patient reevaluations—particularly early on—with attention to signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal and excessive sedation from medications. Additionally, although most patients with alcohol withdrawal respond to standard treatment that includes benzodiazepines, optimal nutrition, and good supportive care, a subgroup may resist therapy (resistant alcohol withdrawal). Therefore, Mr. J—and others with resistant alcohol withdrawal—may require large doses of benzodiazepines and additional sedatives and undergo complicated hospitalizations.9 Nonetheless, as exemplified by Mr. J, symptom-triggered protocols for alcohol withdrawal can result in potential morbidity and mortality.

Common symptoms of alcohol withdrawal include autonomic hyperactivity, tremor, insomnia, nausea, vomiting, agitation, anxiety, grand mal seizures, and transient visual, tactile, or auditory hallucinations.5 These symptoms result, in part, from the effects of chronic alcohol exposure on brain γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate systems. Alcohol acutely enhances presynaptic GABA release through allosteric modulation at GABAA receptors and inhibits glutamate function through antagonism of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Chronic alcohol exposure elicits compensatory downregulated GABAA and upregulated NMDA expression.

When alcohol intake abruptly stops and its acute effects dissipate, the sudden reduction in GABAergic tone and increase in glutamatergic tone cause alcohol withdrawal symptoms.6 Benzodiazepines, which bind at the benzodiazepine site on the GABAA receptor and, similar to alcohol, acutely enhance GABA and inhibit glutamate signaling, are the standard of care for alcohol withdrawal because they reduce anxiety and the risk of seizures and delirium tremens, which is a severe form of alcohol withdrawal characterized by disturbance in consciousness and cognition and hallucinations.5,6

Table

Benefits of symptom-triggered vs fixed scheduled therapy for alcohol withdrawal

| ST | FS | Benefits of ST | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy in alcohol withdrawal | Yes | Yes | |

| Flexibility in dosing with fluctuations in CIWA-Ar score | Yes | No | Less medication can be given overall if alcohol withdrawal signs resolve rapidly |

| Lower total benzodiazepine doses | + | – | Smaller chance of side effects such as oversedation, paradoxical agitation, delirium due to benzodiazepine intoxication, or respiratory depression |

| Fewer complications of higher benzodiazepine doses | + | – | Reduced risk of prolonged hospitalization, morbidity from aspiration pneumonia, or need to administer a reversal agent such as flumazenil |

| + = more likely; – = less likely CIWA-Ar: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised; FS: fixed scheduled; ST: symptom-triggered Bibliography Amato L, Minozzi S, Vecchi S, et al. Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD005063. Cassidy EM, O’Sullivan I, Bradshaw P, et al. Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome in the emergency department: a comparison with the standard fixed dose benzodiazepine regimen [published online ahead of print October 19, 2011]. Emerg Med J. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2011-200509. Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121. DeCarolis DD, Rice KL, Ho L, et al. Symptom-driven lorazepam protocol for treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal delirium in the intensive care unit. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(4):510-518. Jaeger TM, Lohr RH, Pankratz VS. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome in medical inpatients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(7):695-701. Weaver MF, Hoffman HJ, Johnson RE, et al. Alcohol withdrawal pharmacotherapy for inpatients with medical comorbidity. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(2):17-24. | |||

Factors influencing CIWA-Ar score

Vital signs monitoring. One limitation of the CIWA-Ar is that vital signs—an objective measurement of alcohol withdrawal— are not used to determine the score. Indeed, Mr. J presented with vital sign dysregulation. However, research suggests that the best predictor of high withdrawal scores includes groups of symptoms rather than individual symptoms.10 In that study, pulse and blood pressure did not correlate with withdrawal severity. Pulse and blood pressure elevations occur in alcohol withdrawal, but other signs and symptoms are more reliable in assessing withdrawal severity. This is clinically important because physicians often prescribe medications for alcohol withdrawal treatment based on pulse and blood pressure measures.1 This needs to be balanced against research that found a systolic blood pressure >150 mm Hg and axillary temperature >38°C can predict development of DTs in patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal.7

Lorazepam-induced disinhibition. Benzodiazepines affect functions associated with processing within the orbital prefrontal cortex,11 including response inhibition and socially acceptable behavior, and impairment in this functioning can result in behavioral disinhibition.12 This effect could account for the apparent paradoxical clinical observation of aggression in benzodiazepine-sedated patients.13 Because agitation is scored on the CIWA-Ar,1,10 falsely elevated scores caused by interpreting benzodiazepine-induced aggression as agitation could result in patients (such as Mr. J) receiving more lorazepam, therefore perpetuating this cycle.

Comorbid anxiety disorders also could falsely accentuate CIWA-Ar scores. For example, the odds of an alcohol dependence diagnosis are 2 to 3 times greater among patients with an anxiety disorder.14 Additionally, the lifetime prevalence of comorbid alcohol dependence for patients with GAD—such as Mr. J— is 30% to 35%.14,15

Alcohol withdrawal can be more severe in patients with alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders because evidence suggests the neurochemical processes underlying both are similar and potentially additive. Studies have shown that these dual diagnosis patients experience more severe symptoms of alcohol withdrawal as assessed by total CIWA-Ar score than those without an anxiety disorder.15 Although such patients may require more aggressive pharmacologic treatment, the dangers of higher benzodiazepine dosages may be even greater.

Benzodiazepine-induced delirium. A recent meta-analysis suggested that benzodiazepines may be associated with an increased risk of delirium.16 Longer-acting benzodiazepines may be associated with increased risk of delirium compared with short-acting agents, and higher doses during a 24-hour period may be associated with increased risk of delirium compared with lower doses. However, wide confidence intervals imply significant uncertainty with these results, and not all patients in the studies reviewed were undergoing alcohol detoxification.16 Benzodiazepines have been reported to accentuate delirium when used to treat DTs.17

We postulate that although Mr. J received lorazepam—a short- to moderate-acting benzodiazepine with a half-life of 12 to 16 hours18—the cumulative dose was high enough to have accentuated—rather than attenuated—delirium.16

Personality disorders. Comorbid alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and personality disorders are well documented. One study found the prevalence of personality disorders in AUDs ranged from 22% to 78%.19 Psychologically, drinking to cope with negative subjective states and emotions (coping motives) and drinking to enhance positive emotions (enhancement motives) may explain the relation between Cluster B personality disorders and AUDs.20

Research on prefrontal functioning in alcoholics and individuals with antisocial personality disorder symptoms has suggested that both groups may be impaired on tasks sensitive to compromised orbitofrontal functioning.21 The orbitofrontal system is essential for maintaining normal inhibitory influences on behavior.22 Benzodiazepines can increase the likelihood of developing disinhibition or impulsivity, which are symptoms of antisocial personality disorder. Because Mr. J had antisocial personality disorder, treating his alcohol withdrawal with a benzodiazepine could have accentuated these symptoms, which were subsequently “treated” with additional lorazepam, therefore worsening the cycle.

Medical comorbidities. The CIWA-Ar relies on autonomic signs and subjective symptoms and was not designed for use in nonverbal patients in the ICU. It is possible that the presence of other acute illnesses may contribute to increased CIWA-Ar scores, but we are unaware of any studies that have evaluated such factors.23

However, tremor, which is scored on the CIWA-Ar, can falsely elevate scores if it is caused by something other than acute alcohol withdrawal. Although essential tremors attenuate with acute alcohol use, chronic alcohol use can result in parkinsonism with a resting tremor, and cerebellar degeneration, which can include an action tremor and cerebellar 3-Hz leg tremor.24 Finally, hepatic encephalopathy—a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by disturbances in consciousness, mood, behavior, and cognition—can occur in patients with advanced liver disease, which may be precipitated by alcohol use. The clinical presentation and symptom severity of hepatic encephalopathy varies from minor cognitive impairment to gross disorientation, confusion, and agitation,25 all of which can elevate CIWA-Ar scores.

The role of disinhibition

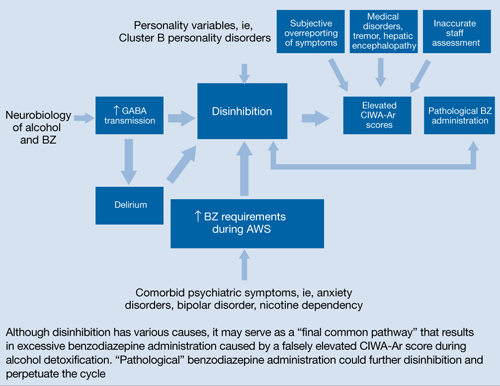

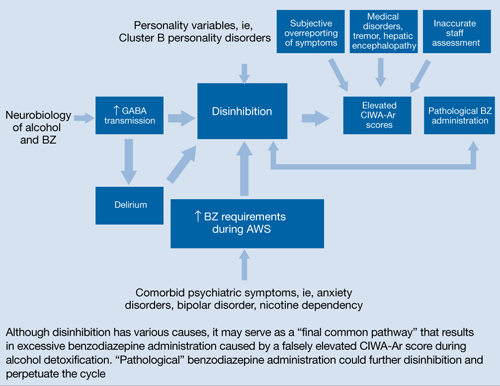

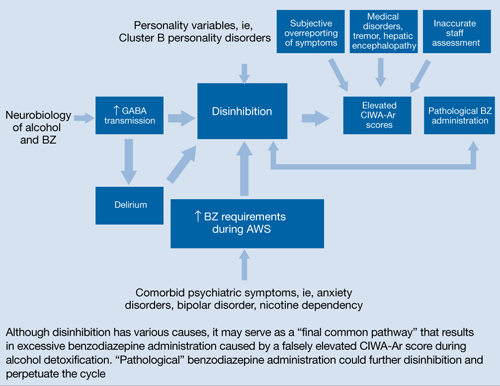

Disinhibition could serve as the “final common pathway” through which CIWA-Ar scores can be falsely elevated.11 For a Figure that illustrates this, see below. Mr. J presented with several variables that could have elevated his CIWA-Ar score; additional potential factors include other psychiatric diagnoses such as bipolar disorder, opiate withdrawal, dementia, drug-seeking behavior, or malingering.26,27

Treating disinhibition in patients with alcohol withdrawal. Continuing to administer escalating doses of benzodiazepines is counterintuitive for benzodiazepine-induced disinhibition. In a study of alcohol withdrawal in rats, antipsychotics evaluated had some beneficial effects on alcohol withdrawal signs.28 In this study, the comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics was as follows: risperidone = quetiapine > ziprasidone > clozapine > olanzapine.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine’s practice guideline advises against using antipsychotics as the sole agent for DTs because these agents are associated with a longer duration of delirium, higher complication rates, and higher mortality.28 However, antipsychotics have a role as an adjunct to benzodiazepines when benzodiazepines don’t sufficiently control agitation, thought disorder, or perceptual disturbances. Although haloperidol use is well established in this scenario, chlorpromazine is contraindicated because it is epileptogenic, and little information is available on atypical antipsychotics.29 If Mr. J had not responded to tapering lorazepam, evidence would support using haloperidol.

Figure: Unifying concept for pathological BZ administration during alcohol withdrawal syndrome: Disinhibition

AWS: alcohol withdrawal syndrome; BZ: benzodiazepine; CIWA-Ar: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised; GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid

Source: Reference 11Related Resources

- Myrick H, Anton RF. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1998;22(1):38-43. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh22-1/38-43.pdf.

- Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of the Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD008537.

Drug Brand Names

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Flumazenil • Romazicon

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Spiegel is on the speaker’s bureau of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

Drs. Kumari and Petri report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Amy Herndon for her help in preparing this article.

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Knott DH, Lerner WD, Davis-Knott T, et al. Decision for alcohol detoxication: a method to standardize patient evaluation. Postgrad Med. 1981;69(5):65-69, 72-75, 78.

3. Wiehl WO, Hayner G, Galloway G. Haight Ashbury Free Clinics’ drug detoxification protocols—Part 4: alcohol. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1994;26(1):57-59.

4. Bostwick JM, Lapid MI. False positives on the clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol-revised: is this scale appropriate for use in the medically ill? Psychosomatics. 2004;45(3):256-261.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

6. Schacht JP, Randall PK, Waid LR, et al. Neurocognitive performance, alcohol withdrawal, and effects of a combination of flumazenil and gabapentin in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(11):2030-2038.

7. Monte R, Rabuñal R, Casariego E, et al. Risk factors for delirium tremens in patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome in a hospital setting. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(7):690-694.

8. Saitz R, O’Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):881-907.

9. Hack JB, Hoffmann RS, Nelson LS. Resistant alcohol withdrawal: does an unexpectedly large sedative requirement identify these patients early? J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):55-60.

10. Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Krupitsky E, et al. Multidimensionality of the Alcohol Withdrawal Symptom Checklist: a factor analysis of the Alcohol Withdrawal Symptom Checklist and CIWA-Ar. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(4):612-618.

11. Deakin JB, Aitken MR, Dowson JH, et al. Diazepam produces disinhibitory cognitive effects in male volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;173(1-2):88-97.

12. Hornberger M, Geng J, Hodges JR. Convergent grey and white matter evidence of orbitofrontal cortex changes related to disinhibition in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(pt 9):2502-2512.

13. Jones KA, Nielsen S, Bruno R, et al. Benzodiazepines - their role in aggression and why GPs should prescribe with caution. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40(11):862-865.

14. Scott EL, Hulvershorn L. Anxiety disorders with comorbid substance abuse. Psychiatric Times. 2011; 28(9).

15. Faingold CL, Knapp DJ, Chester JA, et al. Integrative neurobiology of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome—from anxiety to seizures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(2):268-278.

16. Clegg A, Young JB. Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40(1):23-29.

17. Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, et al. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274-279.

18. Lader M. Benzodiazepines revisited—will we ever learn? Addiction. 2011;106(12):2086-2109.

19. Mellos E, Liappas I, Paparrigopoulos T. Comorbidity of personality disorders with alcohol abuse. In Vivo. 2010;24(5):761-769.

20. Tragesser SL, Sher KJ, Trull TJ, et al. Personality disorder symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use and consequences: cross-sectional and prospective mediation. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(3):282-292.

21. Oscar-Berman M, Valmas MM, Sawyer KS, et al. Frontal brain dysfunction in alcoholism with and without antisocial personality disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:309-326.

22. Dom G, De Wilde B, Hulstijn W, et al. Behavioural aspects of impulsivity in alcoholics with and without a cluster-B personality disorder. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41(4):412-420.

23. de Wit M, Jones DG, Sessler CN, et al. Alcohol-use disorders in the critically ill patient. Chest. 2010;138(4):994-1003.

24. Mostile G, Jankovic J. Alcohol in essential tremor and other movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2010;25(14):2274-2284.

25. Crone CC, Gabriel GM, DiMartini A. An overview of psychiatric issues in liver disease for the consultation-liaison psychiatrist. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(3):188-205.

26. Reoux JP, Oreskovich MR. A comparison of two versions of the clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol: the CIWA-Ar and CIWA-AD. Am J Addict. 2006;15(1):85-93.

27. Gray S, Borgundvaag B, Sirvastava A, et al. Feasibility and reliability of the SHOT: a short scale for measuring pretreatment severity of alcohol withdrawal in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(10):1048-1054.

28. Uzbay TI. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and ethanol withdrawal syndrome: a review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47(1):33-41.

29. McKeon A, Frye MA, Delanty N. The alcohol withdrawal syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(8):854-862.

Clinicians often use the symptom-triggered Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Scale, Revised (CIWA-Ar)1 to assess patients’ risk for alcohol withdrawal because it has well-documented reliability, reproducibility, and validity based on comparison with ratings by expert clinicians.2,3 The CIWA-Ar commonly is used to determine when to administer lorazepam to limit or prevent morbidity and mortality in patients who are at risk of or are experiencing alcohol withdrawal. Refined to a list of 10 signs and symptoms, the CIWA-Ar is easy to administer and useful in a variety of clinical settings. The maximum score is 67, and patients with a score >15 are at increased risk for severe alcohol withdrawal.1 For a downloadable copy of the CIWA-Ar, click here.

Despite the benefits of using the CIWA-Ar, qualitative description of certain alcohol withdrawal symptoms is prone to subjective misinterpretation and can result in falsely elevated scores, excessive benzodiazepine administration, and associated sequelae.4 This article describes such a scenario, and examines factors that can contribute to a falsely elevated CIWA-Ar score.

CASE REPORT: Resistant alcohol withdrawal

Mr. J, age 24, is referred to the consultation-liaison service at our teaching hospital for “overall psychiatric assessment and help with alcohol withdrawal.” When brought to the hospital, Mr. J was experiencing diaphoresis and tachycardia. During the interview, he says he “experiences withdrawal symptoms all the time, so I am familiar with the signs.”

Mr. J is cooperative with the interview. Psychomotor agitation or retardation is not noted. His speech is goal-directed, his mood is “calm,” and his affect is within normal range. His thought content is devoid of psychoses or lethal ideations. On Mini-Mental State Examination, Mr. J scores 28 out of 30, which indicates normal cognitive functioning. He reports drinking eight 40-oz bottles of beer daily for the past 3 months. He started drinking alcohol at age 14 and has had only one 1-year period of sobriety. He denies using illicit drugs and his urine drug screen is unremarkable. Mr. J has a history of delirium tremens (DTs), no significant medical history, and was not taking any medications when admitted. His psychiatric history includes generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and antisocial personality disorder and his family history is significant for alcohol dependence.

Laboratory workup is unremarkable except for a blood alcohol level of 0.23%. Review of systems is significant for mild tremor but no other symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Physical examination is within normal limits.

Mr. J is started on a symptom-trigger alcohol detoxification protocol using the CIWA-Ar. Based on an elevated CIWA-Ar score of 33, he receives lorazepam IV, 11 mg on his first day of hospitalization and 8 mg on the second day. On the third day, Mr. J is agitated and pulls his IV lines in an attempt to leave. Over the next 24 hours, his blood pressure ranges from 136/90 mm Hg to 169/92 mm Hg and his pulse ranges from 94 to 115 beats per minute. He is given lorazepam, 30 mg, and is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

At this time, Mr. J’s Delirium Rating Scale (DRS) score is 20 (maximum: 32). He remains in the ICU on lorazepam, 25 mg/hr. After 3 days in the ICU, lorazepam is titrated and stopped 2 days later. After lorazepam is stopped, Mr. J’s DRS score is 0, his vital signs are stable, and he no longer demonstrates signs or symptoms of DTs or alcohol withdrawal. He is discharged 1 day later.

Symptom-triggered treatment

Alcohol withdrawal symptoms mainly are caused by the effects of chronic alcohol exposure on brain γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate systems; benzodiazepines are the standard of care (Box).5,6 Mr. J had a history of DTs, which is a risk factor for more severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms and recurrence of DTs.7 Some authors report that fixed dosing intervals are the “gold standard therapy” for alcohol withdrawal, and may be preferable for patients with a history of DTs.8 However, Mr. J was placed on a symptom-triggered protocol, which is standard at our hospital. The decision to implement this protocol was based on concerns of oversedation and possible respiratory suppression. Clinical trials have demonstrated that compared with fixed scheduled therapy for alcohol withdrawal, symptom-triggered protocols result in a reduced need for benzodiazepines (Table).

This treatment strategy requires frequent patient reevaluations—particularly early on—with attention to signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal and excessive sedation from medications. Additionally, although most patients with alcohol withdrawal respond to standard treatment that includes benzodiazepines, optimal nutrition, and good supportive care, a subgroup may resist therapy (resistant alcohol withdrawal). Therefore, Mr. J—and others with resistant alcohol withdrawal—may require large doses of benzodiazepines and additional sedatives and undergo complicated hospitalizations.9 Nonetheless, as exemplified by Mr. J, symptom-triggered protocols for alcohol withdrawal can result in potential morbidity and mortality.

Common symptoms of alcohol withdrawal include autonomic hyperactivity, tremor, insomnia, nausea, vomiting, agitation, anxiety, grand mal seizures, and transient visual, tactile, or auditory hallucinations.5 These symptoms result, in part, from the effects of chronic alcohol exposure on brain γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate systems. Alcohol acutely enhances presynaptic GABA release through allosteric modulation at GABAA receptors and inhibits glutamate function through antagonism of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Chronic alcohol exposure elicits compensatory downregulated GABAA and upregulated NMDA expression.

When alcohol intake abruptly stops and its acute effects dissipate, the sudden reduction in GABAergic tone and increase in glutamatergic tone cause alcohol withdrawal symptoms.6 Benzodiazepines, which bind at the benzodiazepine site on the GABAA receptor and, similar to alcohol, acutely enhance GABA and inhibit glutamate signaling, are the standard of care for alcohol withdrawal because they reduce anxiety and the risk of seizures and delirium tremens, which is a severe form of alcohol withdrawal characterized by disturbance in consciousness and cognition and hallucinations.5,6

Table

Benefits of symptom-triggered vs fixed scheduled therapy for alcohol withdrawal

| ST | FS | Benefits of ST | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy in alcohol withdrawal | Yes | Yes | |

| Flexibility in dosing with fluctuations in CIWA-Ar score | Yes | No | Less medication can be given overall if alcohol withdrawal signs resolve rapidly |

| Lower total benzodiazepine doses | + | – | Smaller chance of side effects such as oversedation, paradoxical agitation, delirium due to benzodiazepine intoxication, or respiratory depression |

| Fewer complications of higher benzodiazepine doses | + | – | Reduced risk of prolonged hospitalization, morbidity from aspiration pneumonia, or need to administer a reversal agent such as flumazenil |

| + = more likely; – = less likely CIWA-Ar: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised; FS: fixed scheduled; ST: symptom-triggered Bibliography Amato L, Minozzi S, Vecchi S, et al. Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD005063. Cassidy EM, O’Sullivan I, Bradshaw P, et al. Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome in the emergency department: a comparison with the standard fixed dose benzodiazepine regimen [published online ahead of print October 19, 2011]. Emerg Med J. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2011-200509. Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121. DeCarolis DD, Rice KL, Ho L, et al. Symptom-driven lorazepam protocol for treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal delirium in the intensive care unit. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(4):510-518. Jaeger TM, Lohr RH, Pankratz VS. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome in medical inpatients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(7):695-701. Weaver MF, Hoffman HJ, Johnson RE, et al. Alcohol withdrawal pharmacotherapy for inpatients with medical comorbidity. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(2):17-24. | |||

Factors influencing CIWA-Ar score

Vital signs monitoring. One limitation of the CIWA-Ar is that vital signs—an objective measurement of alcohol withdrawal— are not used to determine the score. Indeed, Mr. J presented with vital sign dysregulation. However, research suggests that the best predictor of high withdrawal scores includes groups of symptoms rather than individual symptoms.10 In that study, pulse and blood pressure did not correlate with withdrawal severity. Pulse and blood pressure elevations occur in alcohol withdrawal, but other signs and symptoms are more reliable in assessing withdrawal severity. This is clinically important because physicians often prescribe medications for alcohol withdrawal treatment based on pulse and blood pressure measures.1 This needs to be balanced against research that found a systolic blood pressure >150 mm Hg and axillary temperature >38°C can predict development of DTs in patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal.7

Lorazepam-induced disinhibition. Benzodiazepines affect functions associated with processing within the orbital prefrontal cortex,11 including response inhibition and socially acceptable behavior, and impairment in this functioning can result in behavioral disinhibition.12 This effect could account for the apparent paradoxical clinical observation of aggression in benzodiazepine-sedated patients.13 Because agitation is scored on the CIWA-Ar,1,10 falsely elevated scores caused by interpreting benzodiazepine-induced aggression as agitation could result in patients (such as Mr. J) receiving more lorazepam, therefore perpetuating this cycle.

Comorbid anxiety disorders also could falsely accentuate CIWA-Ar scores. For example, the odds of an alcohol dependence diagnosis are 2 to 3 times greater among patients with an anxiety disorder.14 Additionally, the lifetime prevalence of comorbid alcohol dependence for patients with GAD—such as Mr. J— is 30% to 35%.14,15

Alcohol withdrawal can be more severe in patients with alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders because evidence suggests the neurochemical processes underlying both are similar and potentially additive. Studies have shown that these dual diagnosis patients experience more severe symptoms of alcohol withdrawal as assessed by total CIWA-Ar score than those without an anxiety disorder.15 Although such patients may require more aggressive pharmacologic treatment, the dangers of higher benzodiazepine dosages may be even greater.

Benzodiazepine-induced delirium. A recent meta-analysis suggested that benzodiazepines may be associated with an increased risk of delirium.16 Longer-acting benzodiazepines may be associated with increased risk of delirium compared with short-acting agents, and higher doses during a 24-hour period may be associated with increased risk of delirium compared with lower doses. However, wide confidence intervals imply significant uncertainty with these results, and not all patients in the studies reviewed were undergoing alcohol detoxification.16 Benzodiazepines have been reported to accentuate delirium when used to treat DTs.17

We postulate that although Mr. J received lorazepam—a short- to moderate-acting benzodiazepine with a half-life of 12 to 16 hours18—the cumulative dose was high enough to have accentuated—rather than attenuated—delirium.16

Personality disorders. Comorbid alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and personality disorders are well documented. One study found the prevalence of personality disorders in AUDs ranged from 22% to 78%.19 Psychologically, drinking to cope with negative subjective states and emotions (coping motives) and drinking to enhance positive emotions (enhancement motives) may explain the relation between Cluster B personality disorders and AUDs.20

Research on prefrontal functioning in alcoholics and individuals with antisocial personality disorder symptoms has suggested that both groups may be impaired on tasks sensitive to compromised orbitofrontal functioning.21 The orbitofrontal system is essential for maintaining normal inhibitory influences on behavior.22 Benzodiazepines can increase the likelihood of developing disinhibition or impulsivity, which are symptoms of antisocial personality disorder. Because Mr. J had antisocial personality disorder, treating his alcohol withdrawal with a benzodiazepine could have accentuated these symptoms, which were subsequently “treated” with additional lorazepam, therefore worsening the cycle.

Medical comorbidities. The CIWA-Ar relies on autonomic signs and subjective symptoms and was not designed for use in nonverbal patients in the ICU. It is possible that the presence of other acute illnesses may contribute to increased CIWA-Ar scores, but we are unaware of any studies that have evaluated such factors.23

However, tremor, which is scored on the CIWA-Ar, can falsely elevate scores if it is caused by something other than acute alcohol withdrawal. Although essential tremors attenuate with acute alcohol use, chronic alcohol use can result in parkinsonism with a resting tremor, and cerebellar degeneration, which can include an action tremor and cerebellar 3-Hz leg tremor.24 Finally, hepatic encephalopathy—a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by disturbances in consciousness, mood, behavior, and cognition—can occur in patients with advanced liver disease, which may be precipitated by alcohol use. The clinical presentation and symptom severity of hepatic encephalopathy varies from minor cognitive impairment to gross disorientation, confusion, and agitation,25 all of which can elevate CIWA-Ar scores.

The role of disinhibition

Disinhibition could serve as the “final common pathway” through which CIWA-Ar scores can be falsely elevated.11 For a Figure that illustrates this, see below. Mr. J presented with several variables that could have elevated his CIWA-Ar score; additional potential factors include other psychiatric diagnoses such as bipolar disorder, opiate withdrawal, dementia, drug-seeking behavior, or malingering.26,27

Treating disinhibition in patients with alcohol withdrawal. Continuing to administer escalating doses of benzodiazepines is counterintuitive for benzodiazepine-induced disinhibition. In a study of alcohol withdrawal in rats, antipsychotics evaluated had some beneficial effects on alcohol withdrawal signs.28 In this study, the comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics was as follows: risperidone = quetiapine > ziprasidone > clozapine > olanzapine.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine’s practice guideline advises against using antipsychotics as the sole agent for DTs because these agents are associated with a longer duration of delirium, higher complication rates, and higher mortality.28 However, antipsychotics have a role as an adjunct to benzodiazepines when benzodiazepines don’t sufficiently control agitation, thought disorder, or perceptual disturbances. Although haloperidol use is well established in this scenario, chlorpromazine is contraindicated because it is epileptogenic, and little information is available on atypical antipsychotics.29 If Mr. J had not responded to tapering lorazepam, evidence would support using haloperidol.

Figure: Unifying concept for pathological BZ administration during alcohol withdrawal syndrome: Disinhibition

AWS: alcohol withdrawal syndrome; BZ: benzodiazepine; CIWA-Ar: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised; GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid

Source: Reference 11Related Resources

- Myrick H, Anton RF. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1998;22(1):38-43. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh22-1/38-43.pdf.

- Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of the Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD008537.

Drug Brand Names

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Flumazenil • Romazicon

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Spiegel is on the speaker’s bureau of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

Drs. Kumari and Petri report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Amy Herndon for her help in preparing this article.

Clinicians often use the symptom-triggered Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Scale, Revised (CIWA-Ar)1 to assess patients’ risk for alcohol withdrawal because it has well-documented reliability, reproducibility, and validity based on comparison with ratings by expert clinicians.2,3 The CIWA-Ar commonly is used to determine when to administer lorazepam to limit or prevent morbidity and mortality in patients who are at risk of or are experiencing alcohol withdrawal. Refined to a list of 10 signs and symptoms, the CIWA-Ar is easy to administer and useful in a variety of clinical settings. The maximum score is 67, and patients with a score >15 are at increased risk for severe alcohol withdrawal.1 For a downloadable copy of the CIWA-Ar, click here.

Despite the benefits of using the CIWA-Ar, qualitative description of certain alcohol withdrawal symptoms is prone to subjective misinterpretation and can result in falsely elevated scores, excessive benzodiazepine administration, and associated sequelae.4 This article describes such a scenario, and examines factors that can contribute to a falsely elevated CIWA-Ar score.

CASE REPORT: Resistant alcohol withdrawal

Mr. J, age 24, is referred to the consultation-liaison service at our teaching hospital for “overall psychiatric assessment and help with alcohol withdrawal.” When brought to the hospital, Mr. J was experiencing diaphoresis and tachycardia. During the interview, he says he “experiences withdrawal symptoms all the time, so I am familiar with the signs.”

Mr. J is cooperative with the interview. Psychomotor agitation or retardation is not noted. His speech is goal-directed, his mood is “calm,” and his affect is within normal range. His thought content is devoid of psychoses or lethal ideations. On Mini-Mental State Examination, Mr. J scores 28 out of 30, which indicates normal cognitive functioning. He reports drinking eight 40-oz bottles of beer daily for the past 3 months. He started drinking alcohol at age 14 and has had only one 1-year period of sobriety. He denies using illicit drugs and his urine drug screen is unremarkable. Mr. J has a history of delirium tremens (DTs), no significant medical history, and was not taking any medications when admitted. His psychiatric history includes generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and antisocial personality disorder and his family history is significant for alcohol dependence.

Laboratory workup is unremarkable except for a blood alcohol level of 0.23%. Review of systems is significant for mild tremor but no other symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Physical examination is within normal limits.

Mr. J is started on a symptom-trigger alcohol detoxification protocol using the CIWA-Ar. Based on an elevated CIWA-Ar score of 33, he receives lorazepam IV, 11 mg on his first day of hospitalization and 8 mg on the second day. On the third day, Mr. J is agitated and pulls his IV lines in an attempt to leave. Over the next 24 hours, his blood pressure ranges from 136/90 mm Hg to 169/92 mm Hg and his pulse ranges from 94 to 115 beats per minute. He is given lorazepam, 30 mg, and is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

At this time, Mr. J’s Delirium Rating Scale (DRS) score is 20 (maximum: 32). He remains in the ICU on lorazepam, 25 mg/hr. After 3 days in the ICU, lorazepam is titrated and stopped 2 days later. After lorazepam is stopped, Mr. J’s DRS score is 0, his vital signs are stable, and he no longer demonstrates signs or symptoms of DTs or alcohol withdrawal. He is discharged 1 day later.

Symptom-triggered treatment

Alcohol withdrawal symptoms mainly are caused by the effects of chronic alcohol exposure on brain γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate systems; benzodiazepines are the standard of care (Box).5,6 Mr. J had a history of DTs, which is a risk factor for more severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms and recurrence of DTs.7 Some authors report that fixed dosing intervals are the “gold standard therapy” for alcohol withdrawal, and may be preferable for patients with a history of DTs.8 However, Mr. J was placed on a symptom-triggered protocol, which is standard at our hospital. The decision to implement this protocol was based on concerns of oversedation and possible respiratory suppression. Clinical trials have demonstrated that compared with fixed scheduled therapy for alcohol withdrawal, symptom-triggered protocols result in a reduced need for benzodiazepines (Table).

This treatment strategy requires frequent patient reevaluations—particularly early on—with attention to signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal and excessive sedation from medications. Additionally, although most patients with alcohol withdrawal respond to standard treatment that includes benzodiazepines, optimal nutrition, and good supportive care, a subgroup may resist therapy (resistant alcohol withdrawal). Therefore, Mr. J—and others with resistant alcohol withdrawal—may require large doses of benzodiazepines and additional sedatives and undergo complicated hospitalizations.9 Nonetheless, as exemplified by Mr. J, symptom-triggered protocols for alcohol withdrawal can result in potential morbidity and mortality.

Common symptoms of alcohol withdrawal include autonomic hyperactivity, tremor, insomnia, nausea, vomiting, agitation, anxiety, grand mal seizures, and transient visual, tactile, or auditory hallucinations.5 These symptoms result, in part, from the effects of chronic alcohol exposure on brain γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate systems. Alcohol acutely enhances presynaptic GABA release through allosteric modulation at GABAA receptors and inhibits glutamate function through antagonism of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Chronic alcohol exposure elicits compensatory downregulated GABAA and upregulated NMDA expression.

When alcohol intake abruptly stops and its acute effects dissipate, the sudden reduction in GABAergic tone and increase in glutamatergic tone cause alcohol withdrawal symptoms.6 Benzodiazepines, which bind at the benzodiazepine site on the GABAA receptor and, similar to alcohol, acutely enhance GABA and inhibit glutamate signaling, are the standard of care for alcohol withdrawal because they reduce anxiety and the risk of seizures and delirium tremens, which is a severe form of alcohol withdrawal characterized by disturbance in consciousness and cognition and hallucinations.5,6

Table

Benefits of symptom-triggered vs fixed scheduled therapy for alcohol withdrawal

| ST | FS | Benefits of ST | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy in alcohol withdrawal | Yes | Yes | |

| Flexibility in dosing with fluctuations in CIWA-Ar score | Yes | No | Less medication can be given overall if alcohol withdrawal signs resolve rapidly |

| Lower total benzodiazepine doses | + | – | Smaller chance of side effects such as oversedation, paradoxical agitation, delirium due to benzodiazepine intoxication, or respiratory depression |

| Fewer complications of higher benzodiazepine doses | + | – | Reduced risk of prolonged hospitalization, morbidity from aspiration pneumonia, or need to administer a reversal agent such as flumazenil |

| + = more likely; – = less likely CIWA-Ar: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised; FS: fixed scheduled; ST: symptom-triggered Bibliography Amato L, Minozzi S, Vecchi S, et al. Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD005063. Cassidy EM, O’Sullivan I, Bradshaw P, et al. Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome in the emergency department: a comparison with the standard fixed dose benzodiazepine regimen [published online ahead of print October 19, 2011]. Emerg Med J. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2011-200509. Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121. DeCarolis DD, Rice KL, Ho L, et al. Symptom-driven lorazepam protocol for treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal delirium in the intensive care unit. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(4):510-518. Jaeger TM, Lohr RH, Pankratz VS. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome in medical inpatients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(7):695-701. Weaver MF, Hoffman HJ, Johnson RE, et al. Alcohol withdrawal pharmacotherapy for inpatients with medical comorbidity. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(2):17-24. | |||

Factors influencing CIWA-Ar score

Vital signs monitoring. One limitation of the CIWA-Ar is that vital signs—an objective measurement of alcohol withdrawal— are not used to determine the score. Indeed, Mr. J presented with vital sign dysregulation. However, research suggests that the best predictor of high withdrawal scores includes groups of symptoms rather than individual symptoms.10 In that study, pulse and blood pressure did not correlate with withdrawal severity. Pulse and blood pressure elevations occur in alcohol withdrawal, but other signs and symptoms are more reliable in assessing withdrawal severity. This is clinically important because physicians often prescribe medications for alcohol withdrawal treatment based on pulse and blood pressure measures.1 This needs to be balanced against research that found a systolic blood pressure >150 mm Hg and axillary temperature >38°C can predict development of DTs in patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal.7

Lorazepam-induced disinhibition. Benzodiazepines affect functions associated with processing within the orbital prefrontal cortex,11 including response inhibition and socially acceptable behavior, and impairment in this functioning can result in behavioral disinhibition.12 This effect could account for the apparent paradoxical clinical observation of aggression in benzodiazepine-sedated patients.13 Because agitation is scored on the CIWA-Ar,1,10 falsely elevated scores caused by interpreting benzodiazepine-induced aggression as agitation could result in patients (such as Mr. J) receiving more lorazepam, therefore perpetuating this cycle.

Comorbid anxiety disorders also could falsely accentuate CIWA-Ar scores. For example, the odds of an alcohol dependence diagnosis are 2 to 3 times greater among patients with an anxiety disorder.14 Additionally, the lifetime prevalence of comorbid alcohol dependence for patients with GAD—such as Mr. J— is 30% to 35%.14,15

Alcohol withdrawal can be more severe in patients with alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders because evidence suggests the neurochemical processes underlying both are similar and potentially additive. Studies have shown that these dual diagnosis patients experience more severe symptoms of alcohol withdrawal as assessed by total CIWA-Ar score than those without an anxiety disorder.15 Although such patients may require more aggressive pharmacologic treatment, the dangers of higher benzodiazepine dosages may be even greater.

Benzodiazepine-induced delirium. A recent meta-analysis suggested that benzodiazepines may be associated with an increased risk of delirium.16 Longer-acting benzodiazepines may be associated with increased risk of delirium compared with short-acting agents, and higher doses during a 24-hour period may be associated with increased risk of delirium compared with lower doses. However, wide confidence intervals imply significant uncertainty with these results, and not all patients in the studies reviewed were undergoing alcohol detoxification.16 Benzodiazepines have been reported to accentuate delirium when used to treat DTs.17

We postulate that although Mr. J received lorazepam—a short- to moderate-acting benzodiazepine with a half-life of 12 to 16 hours18—the cumulative dose was high enough to have accentuated—rather than attenuated—delirium.16

Personality disorders. Comorbid alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and personality disorders are well documented. One study found the prevalence of personality disorders in AUDs ranged from 22% to 78%.19 Psychologically, drinking to cope with negative subjective states and emotions (coping motives) and drinking to enhance positive emotions (enhancement motives) may explain the relation between Cluster B personality disorders and AUDs.20

Research on prefrontal functioning in alcoholics and individuals with antisocial personality disorder symptoms has suggested that both groups may be impaired on tasks sensitive to compromised orbitofrontal functioning.21 The orbitofrontal system is essential for maintaining normal inhibitory influences on behavior.22 Benzodiazepines can increase the likelihood of developing disinhibition or impulsivity, which are symptoms of antisocial personality disorder. Because Mr. J had antisocial personality disorder, treating his alcohol withdrawal with a benzodiazepine could have accentuated these symptoms, which were subsequently “treated” with additional lorazepam, therefore worsening the cycle.

Medical comorbidities. The CIWA-Ar relies on autonomic signs and subjective symptoms and was not designed for use in nonverbal patients in the ICU. It is possible that the presence of other acute illnesses may contribute to increased CIWA-Ar scores, but we are unaware of any studies that have evaluated such factors.23

However, tremor, which is scored on the CIWA-Ar, can falsely elevate scores if it is caused by something other than acute alcohol withdrawal. Although essential tremors attenuate with acute alcohol use, chronic alcohol use can result in parkinsonism with a resting tremor, and cerebellar degeneration, which can include an action tremor and cerebellar 3-Hz leg tremor.24 Finally, hepatic encephalopathy—a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by disturbances in consciousness, mood, behavior, and cognition—can occur in patients with advanced liver disease, which may be precipitated by alcohol use. The clinical presentation and symptom severity of hepatic encephalopathy varies from minor cognitive impairment to gross disorientation, confusion, and agitation,25 all of which can elevate CIWA-Ar scores.

The role of disinhibition

Disinhibition could serve as the “final common pathway” through which CIWA-Ar scores can be falsely elevated.11 For a Figure that illustrates this, see below. Mr. J presented with several variables that could have elevated his CIWA-Ar score; additional potential factors include other psychiatric diagnoses such as bipolar disorder, opiate withdrawal, dementia, drug-seeking behavior, or malingering.26,27

Treating disinhibition in patients with alcohol withdrawal. Continuing to administer escalating doses of benzodiazepines is counterintuitive for benzodiazepine-induced disinhibition. In a study of alcohol withdrawal in rats, antipsychotics evaluated had some beneficial effects on alcohol withdrawal signs.28 In this study, the comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics was as follows: risperidone = quetiapine > ziprasidone > clozapine > olanzapine.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine’s practice guideline advises against using antipsychotics as the sole agent for DTs because these agents are associated with a longer duration of delirium, higher complication rates, and higher mortality.28 However, antipsychotics have a role as an adjunct to benzodiazepines when benzodiazepines don’t sufficiently control agitation, thought disorder, or perceptual disturbances. Although haloperidol use is well established in this scenario, chlorpromazine is contraindicated because it is epileptogenic, and little information is available on atypical antipsychotics.29 If Mr. J had not responded to tapering lorazepam, evidence would support using haloperidol.

Figure: Unifying concept for pathological BZ administration during alcohol withdrawal syndrome: Disinhibition

AWS: alcohol withdrawal syndrome; BZ: benzodiazepine; CIWA-Ar: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised; GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid

Source: Reference 11Related Resources

- Myrick H, Anton RF. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1998;22(1):38-43. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh22-1/38-43.pdf.

- Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of the Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD008537.

Drug Brand Names

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Flumazenil • Romazicon

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

Dr. Spiegel is on the speaker’s bureau of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

Drs. Kumari and Petri report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Amy Herndon for her help in preparing this article.

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Knott DH, Lerner WD, Davis-Knott T, et al. Decision for alcohol detoxication: a method to standardize patient evaluation. Postgrad Med. 1981;69(5):65-69, 72-75, 78.

3. Wiehl WO, Hayner G, Galloway G. Haight Ashbury Free Clinics’ drug detoxification protocols—Part 4: alcohol. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1994;26(1):57-59.

4. Bostwick JM, Lapid MI. False positives on the clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol-revised: is this scale appropriate for use in the medically ill? Psychosomatics. 2004;45(3):256-261.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

6. Schacht JP, Randall PK, Waid LR, et al. Neurocognitive performance, alcohol withdrawal, and effects of a combination of flumazenil and gabapentin in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(11):2030-2038.

7. Monte R, Rabuñal R, Casariego E, et al. Risk factors for delirium tremens in patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome in a hospital setting. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(7):690-694.

8. Saitz R, O’Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):881-907.

9. Hack JB, Hoffmann RS, Nelson LS. Resistant alcohol withdrawal: does an unexpectedly large sedative requirement identify these patients early? J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):55-60.

10. Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Krupitsky E, et al. Multidimensionality of the Alcohol Withdrawal Symptom Checklist: a factor analysis of the Alcohol Withdrawal Symptom Checklist and CIWA-Ar. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(4):612-618.

11. Deakin JB, Aitken MR, Dowson JH, et al. Diazepam produces disinhibitory cognitive effects in male volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;173(1-2):88-97.

12. Hornberger M, Geng J, Hodges JR. Convergent grey and white matter evidence of orbitofrontal cortex changes related to disinhibition in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(pt 9):2502-2512.

13. Jones KA, Nielsen S, Bruno R, et al. Benzodiazepines - their role in aggression and why GPs should prescribe with caution. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40(11):862-865.

14. Scott EL, Hulvershorn L. Anxiety disorders with comorbid substance abuse. Psychiatric Times. 2011; 28(9).

15. Faingold CL, Knapp DJ, Chester JA, et al. Integrative neurobiology of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome—from anxiety to seizures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(2):268-278.

16. Clegg A, Young JB. Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40(1):23-29.

17. Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, et al. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274-279.

18. Lader M. Benzodiazepines revisited—will we ever learn? Addiction. 2011;106(12):2086-2109.

19. Mellos E, Liappas I, Paparrigopoulos T. Comorbidity of personality disorders with alcohol abuse. In Vivo. 2010;24(5):761-769.

20. Tragesser SL, Sher KJ, Trull TJ, et al. Personality disorder symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use and consequences: cross-sectional and prospective mediation. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(3):282-292.

21. Oscar-Berman M, Valmas MM, Sawyer KS, et al. Frontal brain dysfunction in alcoholism with and without antisocial personality disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:309-326.

22. Dom G, De Wilde B, Hulstijn W, et al. Behavioural aspects of impulsivity in alcoholics with and without a cluster-B personality disorder. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41(4):412-420.

23. de Wit M, Jones DG, Sessler CN, et al. Alcohol-use disorders in the critically ill patient. Chest. 2010;138(4):994-1003.

24. Mostile G, Jankovic J. Alcohol in essential tremor and other movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2010;25(14):2274-2284.

25. Crone CC, Gabriel GM, DiMartini A. An overview of psychiatric issues in liver disease for the consultation-liaison psychiatrist. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(3):188-205.

26. Reoux JP, Oreskovich MR. A comparison of two versions of the clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol: the CIWA-Ar and CIWA-AD. Am J Addict. 2006;15(1):85-93.

27. Gray S, Borgundvaag B, Sirvastava A, et al. Feasibility and reliability of the SHOT: a short scale for measuring pretreatment severity of alcohol withdrawal in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(10):1048-1054.

28. Uzbay TI. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and ethanol withdrawal syndrome: a review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47(1):33-41.

29. McKeon A, Frye MA, Delanty N. The alcohol withdrawal syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(8):854-862.

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Knott DH, Lerner WD, Davis-Knott T, et al. Decision for alcohol detoxication: a method to standardize patient evaluation. Postgrad Med. 1981;69(5):65-69, 72-75, 78.

3. Wiehl WO, Hayner G, Galloway G. Haight Ashbury Free Clinics’ drug detoxification protocols—Part 4: alcohol. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1994;26(1):57-59.

4. Bostwick JM, Lapid MI. False positives on the clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol-revised: is this scale appropriate for use in the medically ill? Psychosomatics. 2004;45(3):256-261.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

6. Schacht JP, Randall PK, Waid LR, et al. Neurocognitive performance, alcohol withdrawal, and effects of a combination of flumazenil and gabapentin in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(11):2030-2038.

7. Monte R, Rabuñal R, Casariego E, et al. Risk factors for delirium tremens in patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome in a hospital setting. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(7):690-694.

8. Saitz R, O’Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):881-907.

9. Hack JB, Hoffmann RS, Nelson LS. Resistant alcohol withdrawal: does an unexpectedly large sedative requirement identify these patients early? J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):55-60.

10. Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Krupitsky E, et al. Multidimensionality of the Alcohol Withdrawal Symptom Checklist: a factor analysis of the Alcohol Withdrawal Symptom Checklist and CIWA-Ar. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(4):612-618.

11. Deakin JB, Aitken MR, Dowson JH, et al. Diazepam produces disinhibitory cognitive effects in male volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;173(1-2):88-97.

12. Hornberger M, Geng J, Hodges JR. Convergent grey and white matter evidence of orbitofrontal cortex changes related to disinhibition in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(pt 9):2502-2512.

13. Jones KA, Nielsen S, Bruno R, et al. Benzodiazepines - their role in aggression and why GPs should prescribe with caution. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40(11):862-865.

14. Scott EL, Hulvershorn L. Anxiety disorders with comorbid substance abuse. Psychiatric Times. 2011; 28(9).

15. Faingold CL, Knapp DJ, Chester JA, et al. Integrative neurobiology of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome—from anxiety to seizures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(2):268-278.

16. Clegg A, Young JB. Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40(1):23-29.

17. Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, et al. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274-279.

18. Lader M. Benzodiazepines revisited—will we ever learn? Addiction. 2011;106(12):2086-2109.

19. Mellos E, Liappas I, Paparrigopoulos T. Comorbidity of personality disorders with alcohol abuse. In Vivo. 2010;24(5):761-769.

20. Tragesser SL, Sher KJ, Trull TJ, et al. Personality disorder symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use and consequences: cross-sectional and prospective mediation. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(3):282-292.

21. Oscar-Berman M, Valmas MM, Sawyer KS, et al. Frontal brain dysfunction in alcoholism with and without antisocial personality disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:309-326.

22. Dom G, De Wilde B, Hulstijn W, et al. Behavioural aspects of impulsivity in alcoholics with and without a cluster-B personality disorder. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41(4):412-420.

23. de Wit M, Jones DG, Sessler CN, et al. Alcohol-use disorders in the critically ill patient. Chest. 2010;138(4):994-1003.

24. Mostile G, Jankovic J. Alcohol in essential tremor and other movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2010;25(14):2274-2284.

25. Crone CC, Gabriel GM, DiMartini A. An overview of psychiatric issues in liver disease for the consultation-liaison psychiatrist. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(3):188-205.

26. Reoux JP, Oreskovich MR. A comparison of two versions of the clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol: the CIWA-Ar and CIWA-AD. Am J Addict. 2006;15(1):85-93.

27. Gray S, Borgundvaag B, Sirvastava A, et al. Feasibility and reliability of the SHOT: a short scale for measuring pretreatment severity of alcohol withdrawal in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(10):1048-1054.

28. Uzbay TI. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and ethanol withdrawal syndrome: a review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47(1):33-41.

29. McKeon A, Frye MA, Delanty N. The alcohol withdrawal syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(8):854-862.