User login

Clozapine has been available for decades, but relatively little has been published regarding its off-label uses. This data shortage likely is due in part to clozapine’s strict monitoring requirements, and we suspect off-label use is more commonplace than the literature reflects.

Refractory schizophrenia and reduction in suicidal behavior in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder are clozapine’s 2 FDA-approved indications. Clozapine also may be prescribed for other indications, and off-label uses have varying degrees of scientific support.

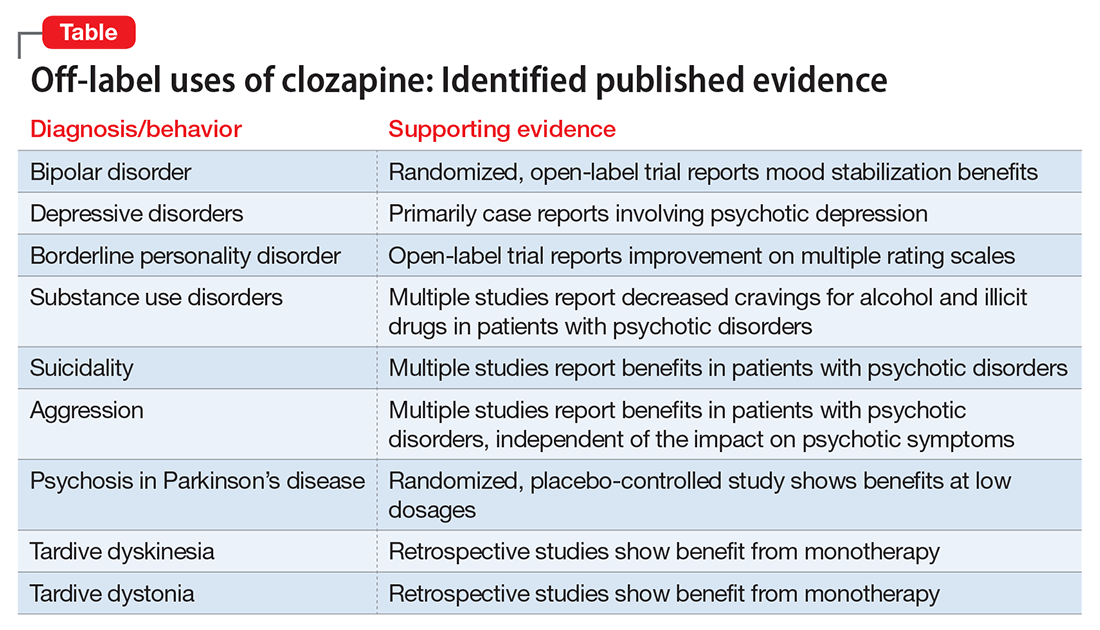

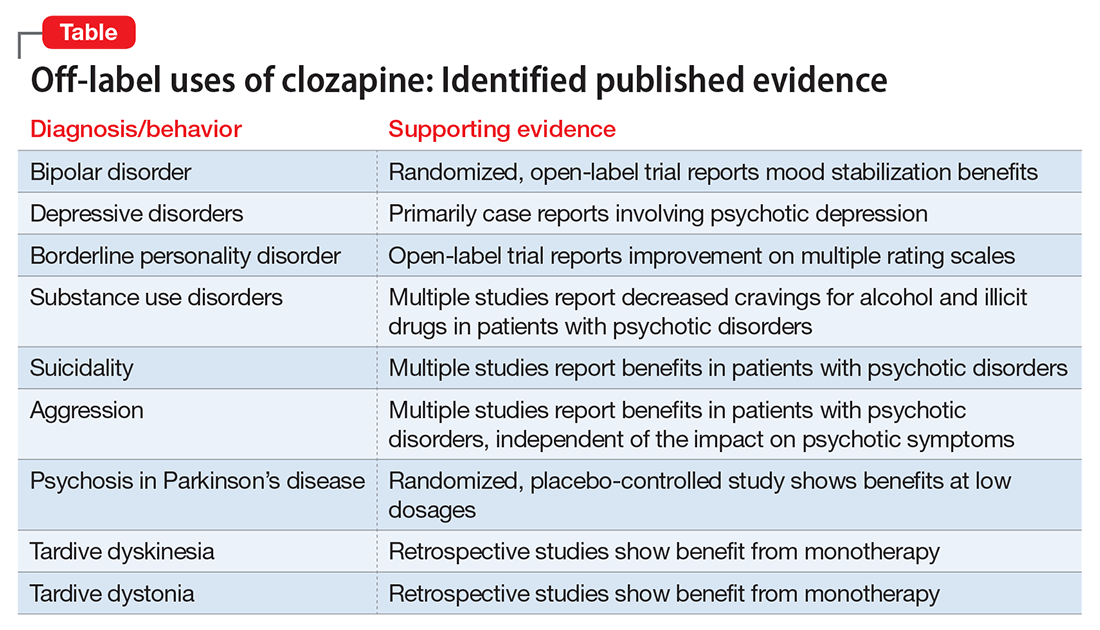

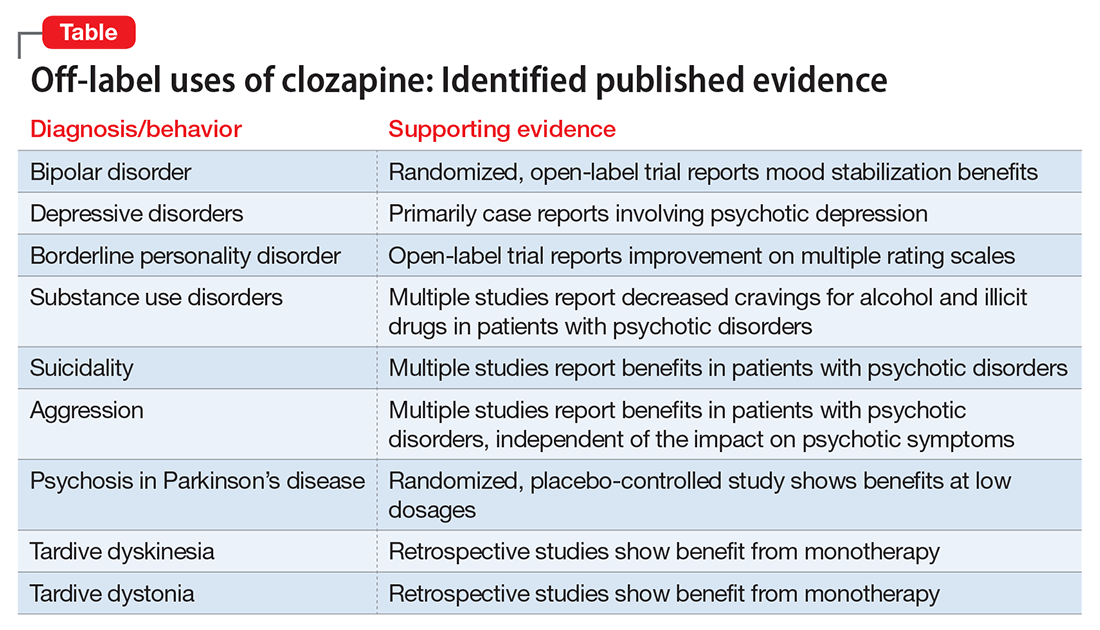

Our goal in “Rediscovering clozapine” has been to deepen clinicians’ appreciation for this unique medication and provide practical clinical guidance for its safe and effective use.1,2 This final segment reviews representative literature regarding clozapine’s off-label use for bipolar disorder and other indications (Table).

At this point, clozapine still is generally most appropriate for use in refractory cases, regardless of the primary condition being treated. We suggest, however, that physicians should at least consider, “Why is clozapine NOT appropriate for this refractory patient?”

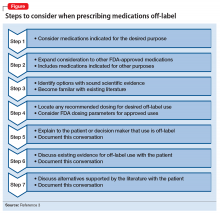

7 Steps define off-label use

Seven steps are useful to consider when prescribing a medication off-label (Figure).3 Off-label prescribing is common in medicine and remains an important component of clinical practice. Sixty percent of antipsychotic prescriptions are written off-label,4 and physicians can prescribe any available medication to any patient for any purpose.

The FDA endorses off-label prescribing: “Good medical practice and the best interests of the patient require that physicians use legally available drugs, biologics and devices according to their best knowledge and judgment.”5 Published case reports and case series provide guidance about the scientific support behind specific off-label indications.

Prescribing off-label based on clinical experience alone is legal, and 1 study reported that 73% of off-label prescriptions written by office-based physicians had little or no scientific support.6 From a medicolegal perspective, prescribing off-label with scientific support is preferred.

Bipolar disorder

Clozapine clearly is established as the most effective antipsychotic for treating refractory schizophrenia. A growing body of evidence supports the off-label use of clozapine for patients with bipolar disorder as well. This literature includes:

- a randomized, open-label trial of maintenance treatment of refractory bipolar disorder7

- 2 studies of treatment of acute mania8,9

- a case series of 3 patients with refractory bipolar disorder and psychotic features who were effectively treated during acute manic episodes with ultra-rapid dose titrations of clozapine.10

In China, clozapine commonly is used to treat bipolar disorder. Results have been positive, and some clinicians there consider clozapine a first-line treatment for this indication.11

In the largest published study of clozapine’s benefits for bipolar disorder, a Danish group presented a retrospective analysis of 326 patients with bipolar disorder (and no history of a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder) treated with clozapine between 1996 and 2007. The study group displayed a significant and clinically relevant reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations, polypharmacy, and self-harm. The authors concluded that clozapine appeared to be an appropriate choice for refractory bipolar disorder and encouraged future investigators to consider randomized controlled studies.12

Major depressive disorder

Published evidence supporting clozapine’s use for refractory unipolar depression is less robust than the evidence for refractory bipolar disorder. One retrospective analysis comparing clozapine treatment for bipolar disorder and unipolar depression concluded that patients with bipolar disorder responded better overall.13

Most case reports involve psychotic depression. One case series discussed clozapine treatment of 3 patients with psychotic depression and reported significant improvement in both depressive and psychotic symptoms.14 Other case reports also described patients with refractory psychotic depression.15,16

We located only 1 case report about using clozapine for depressive symptoms absent psychosis. This case involved a patient who developed recurrent depression, hypersomnia, and behavioral disturbances at age 13 after a viral febrile infection. At age 27, she was hospitalized during an episode and started on low-dose clozapine. After discharge, she remained symptom-free for 30 months on clozapine, 50 to 100 mg/d. Although her symptoms included recurrent depression, her overall clinical picture seemed most consistent with Kleine-Levin syndrome (also known as “Sleeping Beauty” syndrome) rather than a primary mood disorder.17

Borderline personality disorder

Psychotherapy is the mainstay for treating borderline personality disorder (BPD), with pharmacotherapy often added to target symptoms such as anger and impulsivity.18 Some small studies and case series have examined clozapine use for BPD.

An open-label study of 15 inpatients with BPD and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified showed improvement on multiple rating scales with clozapine dosages averaging 250 mg/d.19 In a case series of 22 female inpatients with a primary diagnosis of BPD, clozapine showed beneficial effects in several clinical domains, including symptom severity and frequency of aggressive incidents. The greatest improvement occurred within the first 6 months of treatment.20

Eight patients who continued clozapine after hospital discharge had fewer and shorter subsequent hospitalizations than others with BPD who were not prescribed clozapine at discharge.21 Individual case reports have discussed benefits of clozapine in challenging BPD cases.22-24

Substance use treatment

A growing body of literature suggests that clozapine may reduce cravings for alcohol and illicit drugs because of its unique receptor profile. Much of the data has been collected in dual diagnosis patients taking clozapine primarily to treat schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Patients in 1 study showed a comparable response to clozapine therapy whether they had a history of substance abuse or not. The authors opined that their results demonstrated a more generalizable decrease in cravings and recommended further study.25

In a naturalistic study of 151 dual diagnosis patients with schizophrenia, alcohol use rates decreased significantly among those who received clozapine for psychiatric symptoms. After 3 years, 79% of patients treated with clozapine were in remission from alcohol use, compared with 33.7% of patients treated with other antipsychotics.26

Other studies have reported decreased alcohol and illicit drug use in patients with schizophrenia and concomitant substance use.27,28 Animal studies have displayed similar results, showing decreased alcohol intake with clozapine.29,30

Compelling results have been shown in patients with schizophrenia and Cannabis use disorder. A small randomized trial compared clozapine with other antipsychotics in individuals with schizophrenia and Cannabis use disorder. Clozapine was associated with significantly decreased Cannabis use, independent of overall symptom response or level of functioning.31 An animal study demonstrated an attenuated development of conditioned place preference (classical conditioning) to cocaine. The authors suggested that clozapine should be considered as a future pharmacotherapy to treat cocaine use.32

The literature does not support prescribing clozapine solely for alcohol or illicit drug use, but clozapine merits consideration in patients with schizophrenia and comorbid substance use. This approach may be most beneficial in controlled environments, such as inpatient or residential facilities.

Suicidality

The 2-year International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) was the first to support clozapine’s efficacy in reducing the risk of recurrent suicidal behavior in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.33 InterSePT data were in line with earlier observations, including improvement in reported depression and hopelessness in patients with primary psychotic disorders.34,35 Clozapine’s action at serotonin receptors (in addition to dopamine receptors) may explain the benefits, based on the suspected link between suicide risk and serotonin.34,36

Most published reports regarding clozapine for suicidality involve patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. We found only 1 published case report describing clozapine’s use for recurrent suicidality in a patient with bipolar disorder. The authors described a dramatic reduction in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and hospitalizations after other attempted interventions—including electroconvulsive therapy—had been ineffective.37

Aggression

In the absence of FDA-approved treatments for long-term management of aggression, many clinicians prescribe atypical antipsychotics. With the exception of clozapine, the demonstrated benefits of these medications for reducing aggression are equivocal. Clozapine is thought to be superior among atypical antipsychotics for addressing aggression because of its unique and broad combination of dopaminergic and serotonergic activity. Its effects on the D1-dopamine receptor likely target aggression, and its effects on the serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2A) likely target the impulsivity commonly associated with aggression.38,39

Clozapine has been shown to reduce long-term aggression in patients with psychotic disorders.40-44 Most reports involve individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder because this population is most commonly treated with clozapine. However, clozapine’s anti-aggressive benefits appear not to be solely related to sedation or improvement in psychosis.42,45

What is known about clozapine’s mechanism suggests that its anti-aggressive benefits would extend beyond patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. In a case series of 7 nonpsychotic patients with antisocial personality disorder and psychopathic traits, all displayed benefits with clozapine—particularly in domains of impulsive behavioral dyscontrol and anger.46

Self-injurious behaviors (SIB) and aggression in 2 patients with profound mental retardation were reduced significantly after treatment was switched from risperidone to clozapine.47 In a similar case, SIB and aggression improved in a man with cognitive impairment.48 The case of Mr. C recounts our experience with using clozapine in a patient with cognitive impairment.

CASE REPORT

Daily assaults keep patient hospitalized

Mr. C, age 19 at the end of treatment, had moderate intellectual disability and an extensive history of violence. He grew up in group homes and long-term psychiatric facilities. Immediately after turning 18, he was transferred from an adolescent facility to an adult psychiatric hospital.

Our treatment team tried various combinations of benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics, but Mr. C consistently assaulted 1 or 2 peers daily without clear provocation. Eventually we started him on clozapine, which we titrated to an effective dose (based on a therapeutic serum level). We also added a therapeutic dosage of lithium to address his residual aggression. With the regimen of clozapine and lithium, Mr. C’s assaultive behavior improved dramatically. After going more than 1 year without assaulting a peer, he was placed in the community.

Movement disorders

Parkinson’s disease. The most extensive evidence for treating movement disorders with clozapine involves patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Geriatric psychiatrists commonly use clozapine, particularly at low doses, to treat psychotic symptoms in patients with PD. Because of a relatively low likelihood of extrapyramidal side effects, clozapine and quetiapine are the 2 antipsychotics most often used to treat dopamimetic psychosis in PD.49 In a randomized, placebo-controlled study, low-dose clozapine showed benefits in treating dopamimetic psychosis in PD, without worsening overall motor function.50 (The recent approval of pimavanserin for PD psychosis likely will impact off-label use of clozapine for this condition.)

A retrospective review of patients with PD and Lewy body dementia described benefits of treating psychosis with clozapine.51 Benefits also have been reported in using clozapine to address levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID) absent psychotic symptoms. In an evidence-based review, the Movement Disorder Society described clozapine for LID as “efficacious and possibly useful.”52

Tardive syndromes. In a retrospective review of clozapine use for tardive dyskinesia, 43% of the 30 patients showed improvement, particularly those with concomitant dystonia.53 Another retrospective analysis reported similar outcomes for 48 patients with tardive dyskinesia treated with clozapine.54 Case series and case reports show support for clozapine as monotherapy for tardive dystonia.55

Huntington’s disease. A randomized, double-blind study found little benefit in using clozapine for patients with Huntington’s disease. The authors concluded that, although individual patients may be able to tolerate sufficiently high dosages to improve chorea, clinicians should use restraint when considering clozapine for this population.56

Precautions in older patients. Caution is advised when using clozapine for movement disorders in older individuals, particularly those with concurrent dementia. All antipsychotics, including clozapine,57 carry a “black-box” warning of increased mortality in older adults with dementia.

We hope that this series, “Rediscovering clozapine,” has helped you get reacquainted with this effective medication, employ appropriate caution, and explore off-label uses.

1. Newman WJ, Newman BM. Rediscovering clozapine: after a turbulent history, current guidance on initiating and monitoring. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(7):42-46,48-49.

2. Newman BM, Newman WJ. Rediscovering clozapine: adverse effects develop—what should you do now? Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(8):40-46,48-49.

3. Newman WJ, Xiong GL, Barnhorst AV. Beta-blockers: off-label use in psychiatric disorders. Psychopharm Review. 2013;48(10):73-80.

4. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use—rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “Off-label” and investigational use of marketed drugs, biologics, and medical devices—information sheet. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm126486.htm. Updated January 25, 2016. Accessed November 24, 2015.

6. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021-1026.

7. Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, et al. Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1164-1169.

8. Barbini B, Scherillo P, Benedetti F, et al. Response to clozapine in acute mania is more rapid than that of chlorpromazine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;12(2):109-112.

9. Green AI, Tohen M, Patel JK, et al. Clozapine in the treatment of refractory psychotic mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):982-986.

10. Aksoy-Poyraz C, Turan ¸S, Demirel ÖF, et al. Effectiveness of ultra-rapid dose titration of clozapine for treatment-resistant bipolar mania: case series. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2015;5(4):237-242.

11. Li XB, Tang YL, Wang CY, et al. Clozapine for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(3):235-247.

12. Nielsen J, Kane JM, Correll CU. Real-world effectiveness of clozapine in patients with bipolar disorder: results from a 2-year mirror-image study. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(8):863-869.

13. Banov MD, Zarate CA Jr, Tohen M, et al. Clozapine therapy in refractory affective disorders: polarity predicts response in long-term follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(7):295-300.

14. Ranjan R, Meltzer HY. Acute and long-term effectiveness of clozapine in treatment-resistant psychotic depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40(4):253-258.

15. Dassa D, Kaladjian A, Azorin JM, et al. Clozapine in the treatment of psychotic refractory depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:822-824.

16. Jeyapaul P, Vieweg R. A case study evaluating the use of clozapine in depression with psychotic features. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;5:20.

17. Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ, Ferentinos PP, Kontaxakis VP, et al. Low-dose clozapine monotherapy for recurring episodes of depression, hypersomnia and behavioural disturbances: a case report. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2011;23(4):191-193.

18. Stoffers J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD005653. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005653.pub2.

19. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. Clozapine treatment of borderline patients: a preliminary study. Compr Psychiatry. 1993;34(6):402-405.

20. Frogley C, Anagnostakis K, Mitchell S, et al. A case series of clozapine for borderline personality disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(2):125-134.

21. Parker GF. Clozapine and borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(3):348-349.

22. Chengappa KNR, Baker RW, Sirri C. The successful use of clozapine in ameliorating severe self mutilation in a patient with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(1):76-82.

23. Rutledge E, O’Regan M, Mohan D. Borderline personality disorder and clozapine. Ir J Psychol Med. 2007;24(1):40-41.

24. Vohra AK. Treatment of severe borderline personality disorder with clozapine. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(3):267-269.

25. Buckley P, Thompson P, Way L, et al. Substance abuse among patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: characteristics and implications for clozapine therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(3):385-389.

26. Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, et al. The effects of clozapine on alcohol and drug use disorders among patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26(2):441-449.

27. Zimmet SV, Strous RD, Burgess ES, et al. Effects of clozapine on substance use in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a retrospective survey. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20(1):94-98.

28. Green AI, Noordsy DL, Brunette MF, et al. Substance abuse and schizophrenia: pharmacotherapeutic intervention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(1):61-71.

29. Green AI, Chau DT, Keung WM, et al. Clozapine reduces alcohol drinking in Syrian golden hamsters. Psychiatry Res. 2004;128(1):9-20.

30. Chau DT, Gulick D, Xie H, et al. Clozapine chronically suppresses alcohol drinking in Syrian golden hamsters. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(2):351-356.

31. Brunette MF, Dawson R, O’Keefe CD, et al. A randomized trial of clozapine vs. other antipsychotics for cannabis use disorder in patients with schizophrenia. J Dual Diagn. 2011;7(1-2):50-63.

32. Kosten TA, Nestler EJ. Clozapine attenuates cocaine conditioned place preference. Life Sci. 1994;55(1):9-14.

33. Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al; International Suicide Prevention Trial Study Group. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) [Erratum in: Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):735]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):82-91.

34. Meltzer HY, Okayli G. Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: impact on risk-benefit assessment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):183-190.

35. Sernyak MJ, Desai R, Stolar M, et al. Impact of clozapine on completed suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):931-937.

36. Nordström P, Asberg M. Suicide risk and serotonin. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;6(suppl 6):12-21.

37. Vangala VR, Brown ES, Suppes T. Clozapine associated with decreased suicidality in bipolar disorder: a case report. Bipolar Disord. 1999;1(2):123-124.

38. Meltzer HY. The mechanism of action of novel antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(2):263-287.

39. Meltzer HY. An overview of the mechanism of action of clozapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(suppl B):47-52.

40. Rabinowitz J, Avnon M, Rosenberg V. Effect of clozapine on physical and verbal aggression. Schizophr Res. 1996;22(3):249-255.

41. Spivak B, Roitman S, Vered Y, et al. Diminished suicidal and aggressive behavior, high plasma norepinephrine levels, and serum triglyceride levels in chronic neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenic patients maintained on clozapine. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21(4):245-250.

42. Citrome L, Volavka J, Czobor P, et al. Effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on hostility among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(11):1510-1514.

43. Volavka J, Czobor P, Nolan K, et al. Overt aggression and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(2):225-228.

44. Krakowski MI, Czobar P, Citrome L, et al. Atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of violent patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):622-629.

45. Chiles JA, Davidson P, McBride D. Effects of clozapine on use of seclusion and restraint at a state hospital. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(3):269-271.

46. Brown D, Larkin F, Sengupta S, et al. Clozapine: an effective treatment for seriously violent and psychopathic men with antisocial personality disorder in a UK high-security hospital. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(5):391-402.

47. Hammock R, Levine WR, Schroeder SR. Brief report: effects of clozapine on self-injurious behavior of two risperidone nonresponders with mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31(1):109-113.

48. Hammock RG, Schroeder SR, Levine WR. The effect of clozapine on self-injurious behavior. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25(6):611-626.

49. Morgante L, Epifanio A, Spina E, et al. Quetiapine and clozapine in parkinsonian patients with dopaminergic psychosis [Erratum in: Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27(5):256]. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27(4):153-156.

50. Pollak P, Tison F, Rascol O. Clozapine in drug induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, placebo controlled study with open follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(5):689-695.

51. Lutz UC, Sirfy A, Wiatr G, et al. Clozapine serum concentrations in dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(12):1471-1476.

52. Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Lim SY, et al. The Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Review Update: treatment for the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(suppl 3):S2-S41.

53. Lieberman JA, Saltz BL, Johns CA, et al. The effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:503-510.

54. Naber D, Leppig M, Grohmann R, et al. Efficacy and adverse effects of clozapine in the treatment of schizophrenia and tardive dyskinesia—a retrospective study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1989;99(suppl):S73-S76.

55. Pinninti NR, Faden J, Adityanjee A. Are second-generation antipsychotics useful in tardive dystonia? Clin Neuropharmacol. 2015;38(5):183-197.

56. van Vugt JP, Siesling S, Vergeer M, et al. Clozapine versus placebo in Huntington’s disease: a double blind randomised comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63(1):35-39.

57. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Clozaril (clozapine). Prescribing information. http://clozaril.com/wp-content/themes/eyesite/pi/Clozaril-2015A507-10022015-Approved.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2016.

Clozapine has been available for decades, but relatively little has been published regarding its off-label uses. This data shortage likely is due in part to clozapine’s strict monitoring requirements, and we suspect off-label use is more commonplace than the literature reflects.

Refractory schizophrenia and reduction in suicidal behavior in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder are clozapine’s 2 FDA-approved indications. Clozapine also may be prescribed for other indications, and off-label uses have varying degrees of scientific support.

Our goal in “Rediscovering clozapine” has been to deepen clinicians’ appreciation for this unique medication and provide practical clinical guidance for its safe and effective use.1,2 This final segment reviews representative literature regarding clozapine’s off-label use for bipolar disorder and other indications (Table).

At this point, clozapine still is generally most appropriate for use in refractory cases, regardless of the primary condition being treated. We suggest, however, that physicians should at least consider, “Why is clozapine NOT appropriate for this refractory patient?”

7 Steps define off-label use

Seven steps are useful to consider when prescribing a medication off-label (Figure).3 Off-label prescribing is common in medicine and remains an important component of clinical practice. Sixty percent of antipsychotic prescriptions are written off-label,4 and physicians can prescribe any available medication to any patient for any purpose.

The FDA endorses off-label prescribing: “Good medical practice and the best interests of the patient require that physicians use legally available drugs, biologics and devices according to their best knowledge and judgment.”5 Published case reports and case series provide guidance about the scientific support behind specific off-label indications.

Prescribing off-label based on clinical experience alone is legal, and 1 study reported that 73% of off-label prescriptions written by office-based physicians had little or no scientific support.6 From a medicolegal perspective, prescribing off-label with scientific support is preferred.

Bipolar disorder

Clozapine clearly is established as the most effective antipsychotic for treating refractory schizophrenia. A growing body of evidence supports the off-label use of clozapine for patients with bipolar disorder as well. This literature includes:

- a randomized, open-label trial of maintenance treatment of refractory bipolar disorder7

- 2 studies of treatment of acute mania8,9

- a case series of 3 patients with refractory bipolar disorder and psychotic features who were effectively treated during acute manic episodes with ultra-rapid dose titrations of clozapine.10

In China, clozapine commonly is used to treat bipolar disorder. Results have been positive, and some clinicians there consider clozapine a first-line treatment for this indication.11

In the largest published study of clozapine’s benefits for bipolar disorder, a Danish group presented a retrospective analysis of 326 patients with bipolar disorder (and no history of a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder) treated with clozapine between 1996 and 2007. The study group displayed a significant and clinically relevant reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations, polypharmacy, and self-harm. The authors concluded that clozapine appeared to be an appropriate choice for refractory bipolar disorder and encouraged future investigators to consider randomized controlled studies.12

Major depressive disorder

Published evidence supporting clozapine’s use for refractory unipolar depression is less robust than the evidence for refractory bipolar disorder. One retrospective analysis comparing clozapine treatment for bipolar disorder and unipolar depression concluded that patients with bipolar disorder responded better overall.13

Most case reports involve psychotic depression. One case series discussed clozapine treatment of 3 patients with psychotic depression and reported significant improvement in both depressive and psychotic symptoms.14 Other case reports also described patients with refractory psychotic depression.15,16

We located only 1 case report about using clozapine for depressive symptoms absent psychosis. This case involved a patient who developed recurrent depression, hypersomnia, and behavioral disturbances at age 13 after a viral febrile infection. At age 27, she was hospitalized during an episode and started on low-dose clozapine. After discharge, she remained symptom-free for 30 months on clozapine, 50 to 100 mg/d. Although her symptoms included recurrent depression, her overall clinical picture seemed most consistent with Kleine-Levin syndrome (also known as “Sleeping Beauty” syndrome) rather than a primary mood disorder.17

Borderline personality disorder

Psychotherapy is the mainstay for treating borderline personality disorder (BPD), with pharmacotherapy often added to target symptoms such as anger and impulsivity.18 Some small studies and case series have examined clozapine use for BPD.

An open-label study of 15 inpatients with BPD and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified showed improvement on multiple rating scales with clozapine dosages averaging 250 mg/d.19 In a case series of 22 female inpatients with a primary diagnosis of BPD, clozapine showed beneficial effects in several clinical domains, including symptom severity and frequency of aggressive incidents. The greatest improvement occurred within the first 6 months of treatment.20

Eight patients who continued clozapine after hospital discharge had fewer and shorter subsequent hospitalizations than others with BPD who were not prescribed clozapine at discharge.21 Individual case reports have discussed benefits of clozapine in challenging BPD cases.22-24

Substance use treatment

A growing body of literature suggests that clozapine may reduce cravings for alcohol and illicit drugs because of its unique receptor profile. Much of the data has been collected in dual diagnosis patients taking clozapine primarily to treat schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Patients in 1 study showed a comparable response to clozapine therapy whether they had a history of substance abuse or not. The authors opined that their results demonstrated a more generalizable decrease in cravings and recommended further study.25

In a naturalistic study of 151 dual diagnosis patients with schizophrenia, alcohol use rates decreased significantly among those who received clozapine for psychiatric symptoms. After 3 years, 79% of patients treated with clozapine were in remission from alcohol use, compared with 33.7% of patients treated with other antipsychotics.26

Other studies have reported decreased alcohol and illicit drug use in patients with schizophrenia and concomitant substance use.27,28 Animal studies have displayed similar results, showing decreased alcohol intake with clozapine.29,30

Compelling results have been shown in patients with schizophrenia and Cannabis use disorder. A small randomized trial compared clozapine with other antipsychotics in individuals with schizophrenia and Cannabis use disorder. Clozapine was associated with significantly decreased Cannabis use, independent of overall symptom response or level of functioning.31 An animal study demonstrated an attenuated development of conditioned place preference (classical conditioning) to cocaine. The authors suggested that clozapine should be considered as a future pharmacotherapy to treat cocaine use.32

The literature does not support prescribing clozapine solely for alcohol or illicit drug use, but clozapine merits consideration in patients with schizophrenia and comorbid substance use. This approach may be most beneficial in controlled environments, such as inpatient or residential facilities.

Suicidality

The 2-year International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) was the first to support clozapine’s efficacy in reducing the risk of recurrent suicidal behavior in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.33 InterSePT data were in line with earlier observations, including improvement in reported depression and hopelessness in patients with primary psychotic disorders.34,35 Clozapine’s action at serotonin receptors (in addition to dopamine receptors) may explain the benefits, based on the suspected link between suicide risk and serotonin.34,36

Most published reports regarding clozapine for suicidality involve patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. We found only 1 published case report describing clozapine’s use for recurrent suicidality in a patient with bipolar disorder. The authors described a dramatic reduction in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and hospitalizations after other attempted interventions—including electroconvulsive therapy—had been ineffective.37

Aggression

In the absence of FDA-approved treatments for long-term management of aggression, many clinicians prescribe atypical antipsychotics. With the exception of clozapine, the demonstrated benefits of these medications for reducing aggression are equivocal. Clozapine is thought to be superior among atypical antipsychotics for addressing aggression because of its unique and broad combination of dopaminergic and serotonergic activity. Its effects on the D1-dopamine receptor likely target aggression, and its effects on the serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2A) likely target the impulsivity commonly associated with aggression.38,39

Clozapine has been shown to reduce long-term aggression in patients with psychotic disorders.40-44 Most reports involve individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder because this population is most commonly treated with clozapine. However, clozapine’s anti-aggressive benefits appear not to be solely related to sedation or improvement in psychosis.42,45

What is known about clozapine’s mechanism suggests that its anti-aggressive benefits would extend beyond patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. In a case series of 7 nonpsychotic patients with antisocial personality disorder and psychopathic traits, all displayed benefits with clozapine—particularly in domains of impulsive behavioral dyscontrol and anger.46

Self-injurious behaviors (SIB) and aggression in 2 patients with profound mental retardation were reduced significantly after treatment was switched from risperidone to clozapine.47 In a similar case, SIB and aggression improved in a man with cognitive impairment.48 The case of Mr. C recounts our experience with using clozapine in a patient with cognitive impairment.

CASE REPORT

Daily assaults keep patient hospitalized

Mr. C, age 19 at the end of treatment, had moderate intellectual disability and an extensive history of violence. He grew up in group homes and long-term psychiatric facilities. Immediately after turning 18, he was transferred from an adolescent facility to an adult psychiatric hospital.

Our treatment team tried various combinations of benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics, but Mr. C consistently assaulted 1 or 2 peers daily without clear provocation. Eventually we started him on clozapine, which we titrated to an effective dose (based on a therapeutic serum level). We also added a therapeutic dosage of lithium to address his residual aggression. With the regimen of clozapine and lithium, Mr. C’s assaultive behavior improved dramatically. After going more than 1 year without assaulting a peer, he was placed in the community.

Movement disorders

Parkinson’s disease. The most extensive evidence for treating movement disorders with clozapine involves patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Geriatric psychiatrists commonly use clozapine, particularly at low doses, to treat psychotic symptoms in patients with PD. Because of a relatively low likelihood of extrapyramidal side effects, clozapine and quetiapine are the 2 antipsychotics most often used to treat dopamimetic psychosis in PD.49 In a randomized, placebo-controlled study, low-dose clozapine showed benefits in treating dopamimetic psychosis in PD, without worsening overall motor function.50 (The recent approval of pimavanserin for PD psychosis likely will impact off-label use of clozapine for this condition.)

A retrospective review of patients with PD and Lewy body dementia described benefits of treating psychosis with clozapine.51 Benefits also have been reported in using clozapine to address levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID) absent psychotic symptoms. In an evidence-based review, the Movement Disorder Society described clozapine for LID as “efficacious and possibly useful.”52

Tardive syndromes. In a retrospective review of clozapine use for tardive dyskinesia, 43% of the 30 patients showed improvement, particularly those with concomitant dystonia.53 Another retrospective analysis reported similar outcomes for 48 patients with tardive dyskinesia treated with clozapine.54 Case series and case reports show support for clozapine as monotherapy for tardive dystonia.55

Huntington’s disease. A randomized, double-blind study found little benefit in using clozapine for patients with Huntington’s disease. The authors concluded that, although individual patients may be able to tolerate sufficiently high dosages to improve chorea, clinicians should use restraint when considering clozapine for this population.56

Precautions in older patients. Caution is advised when using clozapine for movement disorders in older individuals, particularly those with concurrent dementia. All antipsychotics, including clozapine,57 carry a “black-box” warning of increased mortality in older adults with dementia.

We hope that this series, “Rediscovering clozapine,” has helped you get reacquainted with this effective medication, employ appropriate caution, and explore off-label uses.

Clozapine has been available for decades, but relatively little has been published regarding its off-label uses. This data shortage likely is due in part to clozapine’s strict monitoring requirements, and we suspect off-label use is more commonplace than the literature reflects.

Refractory schizophrenia and reduction in suicidal behavior in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder are clozapine’s 2 FDA-approved indications. Clozapine also may be prescribed for other indications, and off-label uses have varying degrees of scientific support.

Our goal in “Rediscovering clozapine” has been to deepen clinicians’ appreciation for this unique medication and provide practical clinical guidance for its safe and effective use.1,2 This final segment reviews representative literature regarding clozapine’s off-label use for bipolar disorder and other indications (Table).

At this point, clozapine still is generally most appropriate for use in refractory cases, regardless of the primary condition being treated. We suggest, however, that physicians should at least consider, “Why is clozapine NOT appropriate for this refractory patient?”

7 Steps define off-label use

Seven steps are useful to consider when prescribing a medication off-label (Figure).3 Off-label prescribing is common in medicine and remains an important component of clinical practice. Sixty percent of antipsychotic prescriptions are written off-label,4 and physicians can prescribe any available medication to any patient for any purpose.

The FDA endorses off-label prescribing: “Good medical practice and the best interests of the patient require that physicians use legally available drugs, biologics and devices according to their best knowledge and judgment.”5 Published case reports and case series provide guidance about the scientific support behind specific off-label indications.

Prescribing off-label based on clinical experience alone is legal, and 1 study reported that 73% of off-label prescriptions written by office-based physicians had little or no scientific support.6 From a medicolegal perspective, prescribing off-label with scientific support is preferred.

Bipolar disorder

Clozapine clearly is established as the most effective antipsychotic for treating refractory schizophrenia. A growing body of evidence supports the off-label use of clozapine for patients with bipolar disorder as well. This literature includes:

- a randomized, open-label trial of maintenance treatment of refractory bipolar disorder7

- 2 studies of treatment of acute mania8,9

- a case series of 3 patients with refractory bipolar disorder and psychotic features who were effectively treated during acute manic episodes with ultra-rapid dose titrations of clozapine.10

In China, clozapine commonly is used to treat bipolar disorder. Results have been positive, and some clinicians there consider clozapine a first-line treatment for this indication.11

In the largest published study of clozapine’s benefits for bipolar disorder, a Danish group presented a retrospective analysis of 326 patients with bipolar disorder (and no history of a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder) treated with clozapine between 1996 and 2007. The study group displayed a significant and clinically relevant reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations, polypharmacy, and self-harm. The authors concluded that clozapine appeared to be an appropriate choice for refractory bipolar disorder and encouraged future investigators to consider randomized controlled studies.12

Major depressive disorder

Published evidence supporting clozapine’s use for refractory unipolar depression is less robust than the evidence for refractory bipolar disorder. One retrospective analysis comparing clozapine treatment for bipolar disorder and unipolar depression concluded that patients with bipolar disorder responded better overall.13

Most case reports involve psychotic depression. One case series discussed clozapine treatment of 3 patients with psychotic depression and reported significant improvement in both depressive and psychotic symptoms.14 Other case reports also described patients with refractory psychotic depression.15,16

We located only 1 case report about using clozapine for depressive symptoms absent psychosis. This case involved a patient who developed recurrent depression, hypersomnia, and behavioral disturbances at age 13 after a viral febrile infection. At age 27, she was hospitalized during an episode and started on low-dose clozapine. After discharge, she remained symptom-free for 30 months on clozapine, 50 to 100 mg/d. Although her symptoms included recurrent depression, her overall clinical picture seemed most consistent with Kleine-Levin syndrome (also known as “Sleeping Beauty” syndrome) rather than a primary mood disorder.17

Borderline personality disorder

Psychotherapy is the mainstay for treating borderline personality disorder (BPD), with pharmacotherapy often added to target symptoms such as anger and impulsivity.18 Some small studies and case series have examined clozapine use for BPD.

An open-label study of 15 inpatients with BPD and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified showed improvement on multiple rating scales with clozapine dosages averaging 250 mg/d.19 In a case series of 22 female inpatients with a primary diagnosis of BPD, clozapine showed beneficial effects in several clinical domains, including symptom severity and frequency of aggressive incidents. The greatest improvement occurred within the first 6 months of treatment.20

Eight patients who continued clozapine after hospital discharge had fewer and shorter subsequent hospitalizations than others with BPD who were not prescribed clozapine at discharge.21 Individual case reports have discussed benefits of clozapine in challenging BPD cases.22-24

Substance use treatment

A growing body of literature suggests that clozapine may reduce cravings for alcohol and illicit drugs because of its unique receptor profile. Much of the data has been collected in dual diagnosis patients taking clozapine primarily to treat schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Patients in 1 study showed a comparable response to clozapine therapy whether they had a history of substance abuse or not. The authors opined that their results demonstrated a more generalizable decrease in cravings and recommended further study.25

In a naturalistic study of 151 dual diagnosis patients with schizophrenia, alcohol use rates decreased significantly among those who received clozapine for psychiatric symptoms. After 3 years, 79% of patients treated with clozapine were in remission from alcohol use, compared with 33.7% of patients treated with other antipsychotics.26

Other studies have reported decreased alcohol and illicit drug use in patients with schizophrenia and concomitant substance use.27,28 Animal studies have displayed similar results, showing decreased alcohol intake with clozapine.29,30

Compelling results have been shown in patients with schizophrenia and Cannabis use disorder. A small randomized trial compared clozapine with other antipsychotics in individuals with schizophrenia and Cannabis use disorder. Clozapine was associated with significantly decreased Cannabis use, independent of overall symptom response or level of functioning.31 An animal study demonstrated an attenuated development of conditioned place preference (classical conditioning) to cocaine. The authors suggested that clozapine should be considered as a future pharmacotherapy to treat cocaine use.32

The literature does not support prescribing clozapine solely for alcohol or illicit drug use, but clozapine merits consideration in patients with schizophrenia and comorbid substance use. This approach may be most beneficial in controlled environments, such as inpatient or residential facilities.

Suicidality

The 2-year International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) was the first to support clozapine’s efficacy in reducing the risk of recurrent suicidal behavior in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.33 InterSePT data were in line with earlier observations, including improvement in reported depression and hopelessness in patients with primary psychotic disorders.34,35 Clozapine’s action at serotonin receptors (in addition to dopamine receptors) may explain the benefits, based on the suspected link between suicide risk and serotonin.34,36

Most published reports regarding clozapine for suicidality involve patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. We found only 1 published case report describing clozapine’s use for recurrent suicidality in a patient with bipolar disorder. The authors described a dramatic reduction in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and hospitalizations after other attempted interventions—including electroconvulsive therapy—had been ineffective.37

Aggression

In the absence of FDA-approved treatments for long-term management of aggression, many clinicians prescribe atypical antipsychotics. With the exception of clozapine, the demonstrated benefits of these medications for reducing aggression are equivocal. Clozapine is thought to be superior among atypical antipsychotics for addressing aggression because of its unique and broad combination of dopaminergic and serotonergic activity. Its effects on the D1-dopamine receptor likely target aggression, and its effects on the serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2A) likely target the impulsivity commonly associated with aggression.38,39

Clozapine has been shown to reduce long-term aggression in patients with psychotic disorders.40-44 Most reports involve individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder because this population is most commonly treated with clozapine. However, clozapine’s anti-aggressive benefits appear not to be solely related to sedation or improvement in psychosis.42,45

What is known about clozapine’s mechanism suggests that its anti-aggressive benefits would extend beyond patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. In a case series of 7 nonpsychotic patients with antisocial personality disorder and psychopathic traits, all displayed benefits with clozapine—particularly in domains of impulsive behavioral dyscontrol and anger.46

Self-injurious behaviors (SIB) and aggression in 2 patients with profound mental retardation were reduced significantly after treatment was switched from risperidone to clozapine.47 In a similar case, SIB and aggression improved in a man with cognitive impairment.48 The case of Mr. C recounts our experience with using clozapine in a patient with cognitive impairment.

CASE REPORT

Daily assaults keep patient hospitalized

Mr. C, age 19 at the end of treatment, had moderate intellectual disability and an extensive history of violence. He grew up in group homes and long-term psychiatric facilities. Immediately after turning 18, he was transferred from an adolescent facility to an adult psychiatric hospital.

Our treatment team tried various combinations of benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics, but Mr. C consistently assaulted 1 or 2 peers daily without clear provocation. Eventually we started him on clozapine, which we titrated to an effective dose (based on a therapeutic serum level). We also added a therapeutic dosage of lithium to address his residual aggression. With the regimen of clozapine and lithium, Mr. C’s assaultive behavior improved dramatically. After going more than 1 year without assaulting a peer, he was placed in the community.

Movement disorders

Parkinson’s disease. The most extensive evidence for treating movement disorders with clozapine involves patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Geriatric psychiatrists commonly use clozapine, particularly at low doses, to treat psychotic symptoms in patients with PD. Because of a relatively low likelihood of extrapyramidal side effects, clozapine and quetiapine are the 2 antipsychotics most often used to treat dopamimetic psychosis in PD.49 In a randomized, placebo-controlled study, low-dose clozapine showed benefits in treating dopamimetic psychosis in PD, without worsening overall motor function.50 (The recent approval of pimavanserin for PD psychosis likely will impact off-label use of clozapine for this condition.)

A retrospective review of patients with PD and Lewy body dementia described benefits of treating psychosis with clozapine.51 Benefits also have been reported in using clozapine to address levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID) absent psychotic symptoms. In an evidence-based review, the Movement Disorder Society described clozapine for LID as “efficacious and possibly useful.”52

Tardive syndromes. In a retrospective review of clozapine use for tardive dyskinesia, 43% of the 30 patients showed improvement, particularly those with concomitant dystonia.53 Another retrospective analysis reported similar outcomes for 48 patients with tardive dyskinesia treated with clozapine.54 Case series and case reports show support for clozapine as monotherapy for tardive dystonia.55

Huntington’s disease. A randomized, double-blind study found little benefit in using clozapine for patients with Huntington’s disease. The authors concluded that, although individual patients may be able to tolerate sufficiently high dosages to improve chorea, clinicians should use restraint when considering clozapine for this population.56

Precautions in older patients. Caution is advised when using clozapine for movement disorders in older individuals, particularly those with concurrent dementia. All antipsychotics, including clozapine,57 carry a “black-box” warning of increased mortality in older adults with dementia.

We hope that this series, “Rediscovering clozapine,” has helped you get reacquainted with this effective medication, employ appropriate caution, and explore off-label uses.

1. Newman WJ, Newman BM. Rediscovering clozapine: after a turbulent history, current guidance on initiating and monitoring. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(7):42-46,48-49.

2. Newman BM, Newman WJ. Rediscovering clozapine: adverse effects develop—what should you do now? Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(8):40-46,48-49.

3. Newman WJ, Xiong GL, Barnhorst AV. Beta-blockers: off-label use in psychiatric disorders. Psychopharm Review. 2013;48(10):73-80.

4. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use—rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “Off-label” and investigational use of marketed drugs, biologics, and medical devices—information sheet. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm126486.htm. Updated January 25, 2016. Accessed November 24, 2015.

6. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021-1026.

7. Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, et al. Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1164-1169.

8. Barbini B, Scherillo P, Benedetti F, et al. Response to clozapine in acute mania is more rapid than that of chlorpromazine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;12(2):109-112.

9. Green AI, Tohen M, Patel JK, et al. Clozapine in the treatment of refractory psychotic mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):982-986.

10. Aksoy-Poyraz C, Turan ¸S, Demirel ÖF, et al. Effectiveness of ultra-rapid dose titration of clozapine for treatment-resistant bipolar mania: case series. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2015;5(4):237-242.

11. Li XB, Tang YL, Wang CY, et al. Clozapine for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(3):235-247.

12. Nielsen J, Kane JM, Correll CU. Real-world effectiveness of clozapine in patients with bipolar disorder: results from a 2-year mirror-image study. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(8):863-869.

13. Banov MD, Zarate CA Jr, Tohen M, et al. Clozapine therapy in refractory affective disorders: polarity predicts response in long-term follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(7):295-300.

14. Ranjan R, Meltzer HY. Acute and long-term effectiveness of clozapine in treatment-resistant psychotic depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40(4):253-258.

15. Dassa D, Kaladjian A, Azorin JM, et al. Clozapine in the treatment of psychotic refractory depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:822-824.

16. Jeyapaul P, Vieweg R. A case study evaluating the use of clozapine in depression with psychotic features. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;5:20.

17. Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ, Ferentinos PP, Kontaxakis VP, et al. Low-dose clozapine monotherapy for recurring episodes of depression, hypersomnia and behavioural disturbances: a case report. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2011;23(4):191-193.

18. Stoffers J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD005653. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005653.pub2.

19. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. Clozapine treatment of borderline patients: a preliminary study. Compr Psychiatry. 1993;34(6):402-405.

20. Frogley C, Anagnostakis K, Mitchell S, et al. A case series of clozapine for borderline personality disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(2):125-134.

21. Parker GF. Clozapine and borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(3):348-349.

22. Chengappa KNR, Baker RW, Sirri C. The successful use of clozapine in ameliorating severe self mutilation in a patient with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(1):76-82.

23. Rutledge E, O’Regan M, Mohan D. Borderline personality disorder and clozapine. Ir J Psychol Med. 2007;24(1):40-41.

24. Vohra AK. Treatment of severe borderline personality disorder with clozapine. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(3):267-269.

25. Buckley P, Thompson P, Way L, et al. Substance abuse among patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: characteristics and implications for clozapine therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(3):385-389.

26. Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, et al. The effects of clozapine on alcohol and drug use disorders among patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26(2):441-449.

27. Zimmet SV, Strous RD, Burgess ES, et al. Effects of clozapine on substance use in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a retrospective survey. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20(1):94-98.

28. Green AI, Noordsy DL, Brunette MF, et al. Substance abuse and schizophrenia: pharmacotherapeutic intervention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(1):61-71.

29. Green AI, Chau DT, Keung WM, et al. Clozapine reduces alcohol drinking in Syrian golden hamsters. Psychiatry Res. 2004;128(1):9-20.

30. Chau DT, Gulick D, Xie H, et al. Clozapine chronically suppresses alcohol drinking in Syrian golden hamsters. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(2):351-356.

31. Brunette MF, Dawson R, O’Keefe CD, et al. A randomized trial of clozapine vs. other antipsychotics for cannabis use disorder in patients with schizophrenia. J Dual Diagn. 2011;7(1-2):50-63.

32. Kosten TA, Nestler EJ. Clozapine attenuates cocaine conditioned place preference. Life Sci. 1994;55(1):9-14.

33. Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al; International Suicide Prevention Trial Study Group. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) [Erratum in: Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):735]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):82-91.

34. Meltzer HY, Okayli G. Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: impact on risk-benefit assessment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):183-190.

35. Sernyak MJ, Desai R, Stolar M, et al. Impact of clozapine on completed suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):931-937.

36. Nordström P, Asberg M. Suicide risk and serotonin. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;6(suppl 6):12-21.

37. Vangala VR, Brown ES, Suppes T. Clozapine associated with decreased suicidality in bipolar disorder: a case report. Bipolar Disord. 1999;1(2):123-124.

38. Meltzer HY. The mechanism of action of novel antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(2):263-287.

39. Meltzer HY. An overview of the mechanism of action of clozapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(suppl B):47-52.

40. Rabinowitz J, Avnon M, Rosenberg V. Effect of clozapine on physical and verbal aggression. Schizophr Res. 1996;22(3):249-255.

41. Spivak B, Roitman S, Vered Y, et al. Diminished suicidal and aggressive behavior, high plasma norepinephrine levels, and serum triglyceride levels in chronic neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenic patients maintained on clozapine. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21(4):245-250.

42. Citrome L, Volavka J, Czobor P, et al. Effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on hostility among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(11):1510-1514.

43. Volavka J, Czobor P, Nolan K, et al. Overt aggression and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(2):225-228.

44. Krakowski MI, Czobar P, Citrome L, et al. Atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of violent patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):622-629.

45. Chiles JA, Davidson P, McBride D. Effects of clozapine on use of seclusion and restraint at a state hospital. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(3):269-271.

46. Brown D, Larkin F, Sengupta S, et al. Clozapine: an effective treatment for seriously violent and psychopathic men with antisocial personality disorder in a UK high-security hospital. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(5):391-402.

47. Hammock R, Levine WR, Schroeder SR. Brief report: effects of clozapine on self-injurious behavior of two risperidone nonresponders with mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31(1):109-113.

48. Hammock RG, Schroeder SR, Levine WR. The effect of clozapine on self-injurious behavior. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25(6):611-626.

49. Morgante L, Epifanio A, Spina E, et al. Quetiapine and clozapine in parkinsonian patients with dopaminergic psychosis [Erratum in: Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27(5):256]. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27(4):153-156.

50. Pollak P, Tison F, Rascol O. Clozapine in drug induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, placebo controlled study with open follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(5):689-695.

51. Lutz UC, Sirfy A, Wiatr G, et al. Clozapine serum concentrations in dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(12):1471-1476.

52. Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Lim SY, et al. The Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Review Update: treatment for the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(suppl 3):S2-S41.

53. Lieberman JA, Saltz BL, Johns CA, et al. The effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:503-510.

54. Naber D, Leppig M, Grohmann R, et al. Efficacy and adverse effects of clozapine in the treatment of schizophrenia and tardive dyskinesia—a retrospective study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1989;99(suppl):S73-S76.

55. Pinninti NR, Faden J, Adityanjee A. Are second-generation antipsychotics useful in tardive dystonia? Clin Neuropharmacol. 2015;38(5):183-197.

56. van Vugt JP, Siesling S, Vergeer M, et al. Clozapine versus placebo in Huntington’s disease: a double blind randomised comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63(1):35-39.

57. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Clozaril (clozapine). Prescribing information. http://clozaril.com/wp-content/themes/eyesite/pi/Clozaril-2015A507-10022015-Approved.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2016.

1. Newman WJ, Newman BM. Rediscovering clozapine: after a turbulent history, current guidance on initiating and monitoring. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(7):42-46,48-49.

2. Newman BM, Newman WJ. Rediscovering clozapine: adverse effects develop—what should you do now? Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(8):40-46,48-49.

3. Newman WJ, Xiong GL, Barnhorst AV. Beta-blockers: off-label use in psychiatric disorders. Psychopharm Review. 2013;48(10):73-80.

4. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use—rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “Off-label” and investigational use of marketed drugs, biologics, and medical devices—information sheet. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm126486.htm. Updated January 25, 2016. Accessed November 24, 2015.

6. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021-1026.

7. Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, et al. Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1164-1169.

8. Barbini B, Scherillo P, Benedetti F, et al. Response to clozapine in acute mania is more rapid than that of chlorpromazine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;12(2):109-112.

9. Green AI, Tohen M, Patel JK, et al. Clozapine in the treatment of refractory psychotic mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):982-986.

10. Aksoy-Poyraz C, Turan ¸S, Demirel ÖF, et al. Effectiveness of ultra-rapid dose titration of clozapine for treatment-resistant bipolar mania: case series. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2015;5(4):237-242.

11. Li XB, Tang YL, Wang CY, et al. Clozapine for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(3):235-247.

12. Nielsen J, Kane JM, Correll CU. Real-world effectiveness of clozapine in patients with bipolar disorder: results from a 2-year mirror-image study. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(8):863-869.

13. Banov MD, Zarate CA Jr, Tohen M, et al. Clozapine therapy in refractory affective disorders: polarity predicts response in long-term follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(7):295-300.

14. Ranjan R, Meltzer HY. Acute and long-term effectiveness of clozapine in treatment-resistant psychotic depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40(4):253-258.

15. Dassa D, Kaladjian A, Azorin JM, et al. Clozapine in the treatment of psychotic refractory depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:822-824.

16. Jeyapaul P, Vieweg R. A case study evaluating the use of clozapine in depression with psychotic features. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;5:20.

17. Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ, Ferentinos PP, Kontaxakis VP, et al. Low-dose clozapine monotherapy for recurring episodes of depression, hypersomnia and behavioural disturbances: a case report. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2011;23(4):191-193.

18. Stoffers J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD005653. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005653.pub2.

19. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. Clozapine treatment of borderline patients: a preliminary study. Compr Psychiatry. 1993;34(6):402-405.

20. Frogley C, Anagnostakis K, Mitchell S, et al. A case series of clozapine for borderline personality disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(2):125-134.

21. Parker GF. Clozapine and borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(3):348-349.

22. Chengappa KNR, Baker RW, Sirri C. The successful use of clozapine in ameliorating severe self mutilation in a patient with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(1):76-82.

23. Rutledge E, O’Regan M, Mohan D. Borderline personality disorder and clozapine. Ir J Psychol Med. 2007;24(1):40-41.

24. Vohra AK. Treatment of severe borderline personality disorder with clozapine. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(3):267-269.

25. Buckley P, Thompson P, Way L, et al. Substance abuse among patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: characteristics and implications for clozapine therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(3):385-389.

26. Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, et al. The effects of clozapine on alcohol and drug use disorders among patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26(2):441-449.

27. Zimmet SV, Strous RD, Burgess ES, et al. Effects of clozapine on substance use in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a retrospective survey. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20(1):94-98.

28. Green AI, Noordsy DL, Brunette MF, et al. Substance abuse and schizophrenia: pharmacotherapeutic intervention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(1):61-71.

29. Green AI, Chau DT, Keung WM, et al. Clozapine reduces alcohol drinking in Syrian golden hamsters. Psychiatry Res. 2004;128(1):9-20.

30. Chau DT, Gulick D, Xie H, et al. Clozapine chronically suppresses alcohol drinking in Syrian golden hamsters. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(2):351-356.

31. Brunette MF, Dawson R, O’Keefe CD, et al. A randomized trial of clozapine vs. other antipsychotics for cannabis use disorder in patients with schizophrenia. J Dual Diagn. 2011;7(1-2):50-63.

32. Kosten TA, Nestler EJ. Clozapine attenuates cocaine conditioned place preference. Life Sci. 1994;55(1):9-14.

33. Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, et al; International Suicide Prevention Trial Study Group. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International Suicide Prevention Trial (InterSePT) [Erratum in: Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):735]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):82-91.

34. Meltzer HY, Okayli G. Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: impact on risk-benefit assessment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):183-190.

35. Sernyak MJ, Desai R, Stolar M, et al. Impact of clozapine on completed suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):931-937.

36. Nordström P, Asberg M. Suicide risk and serotonin. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;6(suppl 6):12-21.

37. Vangala VR, Brown ES, Suppes T. Clozapine associated with decreased suicidality in bipolar disorder: a case report. Bipolar Disord. 1999;1(2):123-124.

38. Meltzer HY. The mechanism of action of novel antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(2):263-287.

39. Meltzer HY. An overview of the mechanism of action of clozapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(suppl B):47-52.

40. Rabinowitz J, Avnon M, Rosenberg V. Effect of clozapine on physical and verbal aggression. Schizophr Res. 1996;22(3):249-255.

41. Spivak B, Roitman S, Vered Y, et al. Diminished suicidal and aggressive behavior, high plasma norepinephrine levels, and serum triglyceride levels in chronic neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenic patients maintained on clozapine. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21(4):245-250.

42. Citrome L, Volavka J, Czobor P, et al. Effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on hostility among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(11):1510-1514.

43. Volavka J, Czobor P, Nolan K, et al. Overt aggression and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(2):225-228.

44. Krakowski MI, Czobar P, Citrome L, et al. Atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of violent patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):622-629.

45. Chiles JA, Davidson P, McBride D. Effects of clozapine on use of seclusion and restraint at a state hospital. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(3):269-271.

46. Brown D, Larkin F, Sengupta S, et al. Clozapine: an effective treatment for seriously violent and psychopathic men with antisocial personality disorder in a UK high-security hospital. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(5):391-402.

47. Hammock R, Levine WR, Schroeder SR. Brief report: effects of clozapine on self-injurious behavior of two risperidone nonresponders with mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31(1):109-113.

48. Hammock RG, Schroeder SR, Levine WR. The effect of clozapine on self-injurious behavior. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25(6):611-626.

49. Morgante L, Epifanio A, Spina E, et al. Quetiapine and clozapine in parkinsonian patients with dopaminergic psychosis [Erratum in: Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27(5):256]. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27(4):153-156.

50. Pollak P, Tison F, Rascol O. Clozapine in drug induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, placebo controlled study with open follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(5):689-695.

51. Lutz UC, Sirfy A, Wiatr G, et al. Clozapine serum concentrations in dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(12):1471-1476.

52. Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Lim SY, et al. The Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Review Update: treatment for the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(suppl 3):S2-S41.

53. Lieberman JA, Saltz BL, Johns CA, et al. The effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:503-510.

54. Naber D, Leppig M, Grohmann R, et al. Efficacy and adverse effects of clozapine in the treatment of schizophrenia and tardive dyskinesia—a retrospective study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1989;99(suppl):S73-S76.

55. Pinninti NR, Faden J, Adityanjee A. Are second-generation antipsychotics useful in tardive dystonia? Clin Neuropharmacol. 2015;38(5):183-197.

56. van Vugt JP, Siesling S, Vergeer M, et al. Clozapine versus placebo in Huntington’s disease: a double blind randomised comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63(1):35-39.

57. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Clozaril (clozapine). Prescribing information. http://clozaril.com/wp-content/themes/eyesite/pi/Clozaril-2015A507-10022015-Approved.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2016.