User login

The treatment of hepatitis c virus (HCV) infection is on the brink of major changes with the recent approval of the first direct-acting antiviral agents, the protease inhibitors boceprevir (Victrelis) and telaprevir (Incivek).

Both drugs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Advisory Panel for Chronic Hepatitis C in May 2011 and are believed to significantly improve treatment outcomes for patients with HCV genotype 1 infection.

A MAJOR PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM

HCV infection is a major public health problem. Nearly 4 million people in the United States are infected.6,7 Most patients with acute HCV infection become chronically infected, and up to 25% eventually develop cirrhosis and its complications, making HCV infection the leading indication for liver transplantation.8–10

Chronic HCV infection has a large global impact, with 180 million people affected across all economic and social groups.11 The highest prevalence of HCV has been reported in Egypt (14%), in part due to the use of inadequately sterilized needles in mass programs to treat endemic schistosomiasis. In developed countries, hepatocellular carcinoma associated with HCV has the fastest growing cancer-related death rate.12

CURRENTLY, FEWER THAN 50% OF PATIENTS ARE CURED

The goal of HCV treatment is to eradicate the virus. However, most infected patients (especially in the United States and Europe) are infected with HCV genotype 1, which is the most difficult genotype to treat.

Successful treatment of HCV is defined as achieving a sustained virologic response—ie, the absence of detectable HCV RNA in the serum 24 weeks after completion of therapy. Once a sustained virologic response is achieved, lifetime “cure” of HCV infection is expected in more than 99% of patients.13

The current standard therapy for HCV, pegylated interferon plus ribavirin for 48 weeks, is effective in only 40% to 50% of patients with genotype 1 infection.14 Therefore, assessing predictors of response before starting treatment can help select patients who are most likely to benefit from therapy.

Viral factors associated with a sustained virologic response include HCV genotypes other than genotype 1 and a low baseline viral load.

Beneficial patient-related factors include younger age, nonblack ethnicity, low body weight (≤ 75 kg), low body mass index, absence of insulin resistance, and absence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

More recently, a single-nucleotide polymorphism near the interleukin 28B (IL28B) gene, coding for interferon lambda 3, was found to be associated with a twofold difference in the rates of sustained virologic response: patients with the favorable genotype CC were two times more likely to achieve a sustained virologic response than patients with the CT or TT genotypes.15–17

PROTEASE INHIBITORS: MECHANISM OF ACTION

NS3/4A protease inhibitors rely on the principle of end-product inhibition, in which the cleavage product of the protease (a peptide) acts to inhibit the enzyme activity; this is why they are called peptidomimetics. The active site of the NS3/4A protease is a shallow groove composed of three highly conserved amino acid residues, which may explain why protease inhibitors display high antiviral efficacy but pose a low barrier to the development of resistance.20

Protease inhibitors are prone to resistance

The development of viral resistance to protease inhibitors has been a major drawback to their use in patients with chronic HCV infection.21

HCV is a highly variable virus with many genetically distinct but closely related quasispecies circulating in the blood at any given time. Drug-resistant, mutated variants preexist within the patient’s quasispecies, but only in small quantities because of their lesser replication fitness compared with the wild-type virus.22 When direct-acting antiviral therapy is started, the quantity of the wild-type virus decreases and the mutated virus gains replication fitness. Using protease inhibitors as monotherapy selects resistant viral populations rapidly within a few days or weeks.

HCV subtypes 1a and 1b may have different resistance profiles. With genotype 1a, some resistance-associated amino acid substitutions require only one nucleotide change, but with genotype 1b, two nucleotide changes are needed, making resistance less frequent in patients with HCV genotype 1b.23

BOCEPREVIR

Boceprevir is a specific inhibitor of the HCV viral protease NS3/4A.

In phase 3 clinical trials, boceprevir 800 mg three times a day was used with pegylated interferon alfa-2b (PegIntron) 1.5 μg/kg/week and ribavirin (Rebetol) 600 to 1,400 mg daily according to body weight.

Before patients started taking boceprevir, they went through a 4-week lead-in phase, during which they received pegylated interferon and ribavirin. This schedule appeared to reduce the incidence of viral breakthrough in phase 2 trials, and it produced higher rates of sustained virologic response and lower relapse rates compared with triple therapy without a lead-in phase.

Rapid virologic response was defined as undetectable HCV RNA at week 4 of boceprevir therapy (week 8 of the whole regimen).

Boceprevir in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1: The SPRINT-2 trial

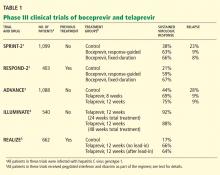

The Serine Protease Inhibitor Therapy 2 (SPRINT-2) trial1 included more than 1,000 previously untreated adults with HCV genotype 1 infection (938 nonblack patients and 159 black patients; two other nonblack patients did not receive any study drug and were not included in the analysis). In this double-blind trial, patients were randomized into three groups:

- The control group received the standard of care with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks

- The response-guided therapy group received boceprevir plus pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 24 weeks after the 4-week lead-in phase; if HCV RNA was undetectable from week 8 to week 24, treatment was considered complete, but if HCV RNA was detectable at any point from week 8 to week 24, pegylated interferon and ribavirin were continued for a total of 48 weeks.

- The fixed-duration therapy group received boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 44 weeks after the lead-in period.

The rate of relapse was 8% and 9% in the boceprevir groups vs 23% in the control group. Patients in the boceprevir groups who had a decrease in HCV RNA of less than 1 log10 during the lead-in phase were found to have a significantly higher rate of boceprevirresistant variants than those who achieved a decrease of HCV RNA of 1 log10 or more.

Boceprevir in previously treated patients with HCV genotype 1: The RESPOND-2 trial

The Retreatment With HCV Serine Protease Inhibitor Boceprevir and PegIntron/Rebetol 2) (RESPOND-2) trial2 was designed to assess the efficacy of combined boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for repeat treatment of patients with HCV genotype 1. These patients had previously undergone standard treatment and had a reduction of 2 log10 or more in HCV RNA after 12 weeks of therapy but with detectable HCV RNA during the therapy period or had had a relapse (defined as undetectable HCV RNA at the end of a previous course of therapy with HCV RNA positivity thereafter). Importantly, null-responders (those who had a reduction of less than 2 log10 in HCV RNA after 12 weeks of therapy) were excluded from this trial.

After a lead-in period of interferon-ribavirin treatment for 4 weeks, 403 patients were assigned to one of three treatment groups:

- Pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 44 weeks (the control group)

- Boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin in a response-guided regimen

- Boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 44 weeks (the fixed-duration group).

Sustained virologic response was achieved in only 21% of patients in the control group. Adding boceprevir increased the rate to 59% in the response-guided therapy group and to 67% in the fixed-duration group. Previous relapsers had better rates than partial responders (69%–75% vs 40%–52%).

Importantly, patients who had a poor response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin during the lead-in phase (defined as having less than a 1-log decrease in the virus before starting boceprevir) had significantly lower rates of sustained virologic response and higher rates of resistance-associated virus variants.

Side effects of boceprevir

Overall, boceprevir is well tolerated. The most common side effects of triple therapy are those usually seen with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, such as flulike symptoms and fatigue (Table 2). However, anemia was more frequent in the boceprevir groups in both SPRINT-2 and RESPOND-2 (45%–50% compared with 20%–29% in the control groups). Erythropoietin was allowed in these studies and was used in about 40% of patients.

The other common side effect associated with boceprevir was dysgeusia (alteration of taste). Dysgeusia was reported by approximately 40% of patients; however, most dysgeusia events were mild to moderate in intensity and did not lead to treatment cessation.

In the SPRINT-2 trial,1 the study drugs had to be discontinued in 12% to 16% of patients in the boceprevir groups because of adverse events, which was similar to the rate (16%) in the control group. Erythropoietin was allowed in this trial, and it was used in 43% of patients in the boceprevir groups compared with 24% in the control group, with discontinuation owing to anemia occurring in 2% and 1% of cases, respectively.

TELAPREVIR

Telaprevir, the other protease NS3/4A inhibitor, has also shown efficacy over current standard therapy in phase 3 clinical trials. It was used in a dose of 750 mg three times a day with pegylated interferon alfa-2a (Pegasys) 180 μg per week and ribavirin (Copegus) 1,000 to 1,200 mg daily according to body weight. A lead-in phase with pegylated interferon and ribavirin was not applied with telaprevir, as it was in the boceprevir trials. Extended rapid virologic response was defined as an undetectable HCV RNA at weeks 4 and 12 of therapy.

Telaprevir in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1

The ADVANCE study3 was a double-blind randomized trial assessing the efficacy and safety of telaprevir in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in more than 1,000 previously untreated patients. The three treatment groups received:

- Telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 8 weeks, followed by pegylated interferon and ribavirin alone for 16 weeks in patients who achieved an extended rapid virologic response (total duration of 24 weeks) or 40 weeks in patients who did not (total duration of 48 weeks)

- Telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 12 weeks, followed by pegylated interferon-ribavirin alone for 12 (total of 24 weeks) or 36 weeks (total of 48 weeks) according to extended rapid virologic response

- Standard care with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks.

The rate of sustained virologic response was 69% in the group that received telaprevir for 8 weeks and 75% in the group that received it for 12 weeks compared with 44% in the control group (P < .0001 for both) (Table 2). Patients infected with HCV genotype 1b had a higher sustained virologic response rate (79%) than those infected with HCV genotype 1a (71%).

Sustained virologic response rates were lower in black patients and patients with bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis, but were still significantly higher in the telaprevir groups than in the control group. The results of this subset analysis were limited by small numbers of patients in each category.

In total, 57% of those who received telaprevir for 8 weeks and 58% of those who received it for 12 weeks achieved an extended rapid virologic response and were able to cut the duration of their therapy in half (from 48 weeks to 24 weeks).

The relapse rates were 9% in the telaprevir groups and 28% in the control group.

The rate of virologic failure was lower in patients who received triple therapy than in those who received interferon-ribavirin alone (8% in the group that got telaprevir for 12 weeks and 13% in the group that got it for 8 weeks, vs 32% in the control group). The failure rate was also lower in patients with HCV genotype 1b infection than in those with genotype 1a.

The ILLUMINATE study4 (Illustrating the Effects of Combination Therapy With Telaprevir) investigated whether longer duration of treatment than that given in the ADVANCE trial increased the rate of sustained virologic response. Previously untreated patients received telaprevir, interferon, and ribavirin for 12 weeks, and those who achieved an extended rapid virologic response were randomized at week 20 to continue interferonribavirin treatment for 24 or 48 weeks of total treatment.

The sustained virologic response rates in patients who achieved an extended rapid virologic response were 92% in the group that received pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks, and 88% in those who received it for 48 weeks. Thus, the results of this study support the use of response-guided therapy for telaprevir-based regimens.

Telaprevir in previously treated patients with HCV genotype 1: The REALIZE trial

In this phase 3 placebo-controlled trial,5 622 patients with prior relapse, partial response, or null response were randomly allocated into one of three groups:

- Telaprevir for 12 weeks plus pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks

- Lead-in for 4 weeks followed by 12 weeks of triple therapy and another 32 weeks of pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks (the control group).

The overall sustained virologic response rates were 66% and 64%, respectively, in the telaprevir groups vs 17% in the control group (P < .0001). The sustained virologic response rates in the telaprevir groups were 83% to 88% in prior relapsers, 54% to 59% in partial responders, and 29% to 33% in null-responders. Of note, patients did not benefit from the lead-in phase.

This was the only trial to investigate the response to triple therapy in null-responders, a group in which treatment has been considered hopeless. A response rate of approximately 31% was encouraging, especially if we compare it with the 5% response rate achieved with the current standard of care with pegylated interferon and ribavirin.

Telaprevir side effects

As with boceprevir-based triple therapy, the most common adverse events were related to pegylated interferon (Table 2).

Nearly 50% of patients who receive telaprevir develop a skin rash that is primarily eczematous, can be managed with topical steroids, and usually resolves when telaprevir is discontinued. Severe rashes occurred in 3% to 6% of patients in the ADVANCE trial,3 and three suspected cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported to the FDA.

Other side effects that were more frequent with telaprevir included pruritus, nausea, diarrhea, and anemia. On average, the hemoglobin level decreased by an additional 1 g/dL in the telaprevir treatment groups compared with the groups that received only pegylated interferon-ribavirin. Erythropoietin use was not allowed in the phase 3 telaprevir studies, and anemia was managed by ribavirin dose reduction.

In the ADVANCE trial,3 study drugs were discontinued owing to adverse events in 7% to 8% of the patients in the telaprevir groups compared with 4% in the control group. In the ILLUMINATE trial,4 17% of patients had to permanently discontinue all study drugs due to adverse events.

FDA-APPROVED TREATMENT REGIMENS FOR BOCEPREVIR AND TELAPREVIR

For treatment algorithms, see the eFigures that accompany this article online.

Boceprevir in previously untreated patients

- Week 0—Start pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 4—Add boceprevir

- Week 8—Measure HCV RNA

- Week 12—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is more than 100 IU/mL

- Week 24—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is detectable

- Week 28—Stop all treatment if HCV RNA was undetectable at weeks 8 and 24

- Week 36—Measure HCV RNA; stop boceprevir

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 1).

Boceprevir in previously treated patients

- Week 0—Start pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 4—Add boceprevir

- Week 8—Measure HCV RNA

- Week 12—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is more than 100 IU/mL

- Week 24—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is detectable

- Week 36—if HCV RNA was not detectable at week 8, stop all treatment now; if HCV RNA was detectable at week 8, stop boceprevir now but continue pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 2).

Telaprevir in previously untreated patients and prior relapsers

- Week 0—start telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin

- Week 4—measure HCV RNA; stop all treatment if it is more than 1,000 IU/mL

- Week 12—Stop telaprevir; measure HCV RNA; stop all treatment if HCV RNA is more than 1,000 IU/mL

- Week 24—Stop pegylated interferon and ribavirin if HCV RNA was undetectable at week 12; measure HCV RNA and stop treatment if it is detectable; otherwise, continue pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 3).

Telaprevir in patients who previously achieved a partial or null response

- Week 0—Start telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin

- Week 4—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is more than 1,000 IU/mL

- Week 12—Measure HCV RNA; stop all treatment if it is more than 1,000 IU/mL; if less than 1,000 IU/mL then stop telaprevir but continue pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 24—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if HCV RNA is detectable

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 4).

Drug interactions with boceprevir and telaprevir

Both boceprevir and telaprevir inhibit cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) and thus are contraindicated in combination with drugs highly dependent on CYP3A for clearance and with drugs for which elevated plasma concentrations are associated with serious adverse events, such as atorvastatin (Lipitor), simvastatin (Zocor), sildenafil (Viagra), midazolam (Versed), and St. John’s wort. Giving potent inducers of CYP3A with boceprevir or telaprevir may lead to lower exposure and loss of efficacy of both protease inhibitors.

EMERGING THERAPIES FOR HCV

Thanks to a better understanding of the biology of HCV infection, the effort to develop new therapeutic agents started to focus on targeting specific steps of the viral life cycle, including attachment, entry into cells, replication, and release.24

Currently, more than 50 clinical trials are evaluating new direct-acting antivirals to treat HCV infection.25 Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies that target the molecular process involved in HCV attachment and entry are being developed.26 The nonstructural protein NS5B (RNA polymerase) is intimately involved in viral replication and represents a promising target.27 Several nucleosides and nonnucleoside protease inhibitors have already entered clinical trials.

The low fidelity of the HCV replication machinery leads to a very high mutation rate, thus enabling the virus to quickly develop mutations that resist agents targeting viral enzymes.28 Therefore, a novel approach is to target host cofactors that are essential for HCV replication. An intriguing study by Lanford et al29 demonstrated that antagonizing microRNA-122 (the most abundant microRNA in the liver and an essential cofactor for viral RNA replication) by the oligonucleotide SPC3649 caused marked and prolonged reduction of HCV viremia in chronically infected chimpanzees.29

Although we are still in the early stages of drug development, the future holds great promise for newer drugs to improve the sustained virologic response, shorten the duration of treatment, improve tolerability with interferon-sparing regimens, and decrease viral resistance.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

With the introduction of the first direct-acting antiviral medications for HCV (boceprevir and telaprevir), 2011 will be marked as the year that changed hepatitis C treatment for the better. Triple therapy with pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and either boceprevir or telaprevir has the potential for increasing the rate of sustained virologic response to around 70% in previously untreated patients and 65% in previously treated patients who are infected with HCV genotype 1. The IL28B polymorphisms appear to play a role in the rate of sustained virologic response achieved with triple therapy, with preliminary data showing a better response rate in patients who have the CC genotype.17

These drugs will add up to $50,000 to the cost of treating hepatitis C virus infection, depending on the drug used and the length of treatment. However, they may be well worth it if they prevent liver failure and the need for transplantation.

Many questions remain, such as how to use these new regimens to treat special patient populations—for example, those with a recurrence of HCV infection after liver transplantation, those co-infected with HCV and human immunodeficiency virus, and those infected with HCV genotypes other than genotype 1.

Other direct-acting antiviral agents that specifically target the replication cycle of HCV are currently in clinical development. In fact, the future has already started with the release of the Interferon-Free Regimen for the Management of HCV (INFORM-1) study results.30 This was the first trial to evaluate an interferon-free regimen for patients with chronic HCV infection using two direct-acting antiviral drugs (the protease inhibitor danoprevir and the polymerase inhibitor RG7128), with promising results.

- Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1195–1206.

- Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1207–1217.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; for the ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2405–2416.

- Sherman KE, Flamm SL, Afdhal NH, et al; for the ILLUMINATE Study Team. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1014–1024.

- Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, et al; for the REALIZE Study Team. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2417–2428.

- Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:705–714.

- Mitchell AE, Colvin HM, Palmer Beasley R. Institute of Medicine recommendations for the prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Hepatology 2010; 51:729–733.

- Kim WR. The burden of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology 2002; 36:S30–S34.

- Marcellin P, Asselah T, Boyer N. Fibrosis and disease progression in hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 36:S47–S56.

- Seeff LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 36:S35–S46.

- Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int 2009; 29(suppl 1):74–81.

- National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of hepatitis C: 2002—June 10–12, 2002. Hepatology 2002; 36:S3–S20.

- Pearlman BL, Traub N. Sustained virologic response to antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a cure and so much more. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:889–900.

- Hoofnagle JH, Seeff LB. Peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2444–2451.

- Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 2009; 461:399–401.

- Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet 2009; 41:1100–1104.

- Thompson AJ, Muir AJ, Sulkowski MS, et al. Interleukin-28B polymorphism improves viral kinetics and is the strongest pretreatment predictor of sustained virologic response in genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology 2010; 139:120–129.e118.

- Nielsen SU, Bassendine MF, Burt AD, Bevitt DJ, Toms GL. Characterization of the genome and structural proteins of hepatitis C virus resolved from infected human liver. J Gen Virol 2004; 85:1497–1507.

- Penin F, Dubuisson J, Rey FA, Moradpour D, Pawlotsky JM. Structural biology of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2004; 39:5–19.

- Nelson DR. The role of triple therapy with protease inhibitors in hepatitis C virus genotype 1 naive patients. Liver Int 2011; 31(suppl 1):53–57.

- Pawlotsky JM. Treatment failure and resistance with direct-acting antiviral drugs against hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2011; 53:1742–1751.

- Monto A, Schooley RT, Lai JC, et al. Lessons from HIV therapy applied to viral hepatitis therapy: summary of a workshop. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105:989–1004.

- McCown MF, Rajyaguru S, Kular S, Cammack N, Najera I. GT-1a or GT-1b subtype-specific resistance profiles for hepatitis C virus inhibitors telaprevir and HCV-796. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:2129–2132.

- Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV. Review article: novel therapeutic options for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 27:866–884.

- Naggie S, Patel K, McHutchison J. Hepatitis C virus directly acting antivirals: current developments with NS3/4A HCV serine protease inhibitors. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65:2063–2069.

- Mir HM, Birerdinc A, Younossi ZM. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against the HCV envelope proteins. Clin Liver Dis 2009; 13:477–486.

- Birerdinc A, Younossi ZM. Emerging therapies for hepatitis C virus. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2010; 15:535–544.

- Khattab MA. Targeting host factors: a novel rationale for the management of hepatitis C virus. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:3472–3479.

- Lanford RE, Hildebrandt-Eriksen ES, Petri A, et al. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science 2010; 327:198–201.

- Gane EJ, Roberts SK, Stedman CA, et al. Oral combination therapy with a nucleoside polymerase inhibitor (RG7128) and danoprevir for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection (INFORM-1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2010; 376:1467–1475.

The treatment of hepatitis c virus (HCV) infection is on the brink of major changes with the recent approval of the first direct-acting antiviral agents, the protease inhibitors boceprevir (Victrelis) and telaprevir (Incivek).

Both drugs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Advisory Panel for Chronic Hepatitis C in May 2011 and are believed to significantly improve treatment outcomes for patients with HCV genotype 1 infection.

A MAJOR PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM

HCV infection is a major public health problem. Nearly 4 million people in the United States are infected.6,7 Most patients with acute HCV infection become chronically infected, and up to 25% eventually develop cirrhosis and its complications, making HCV infection the leading indication for liver transplantation.8–10

Chronic HCV infection has a large global impact, with 180 million people affected across all economic and social groups.11 The highest prevalence of HCV has been reported in Egypt (14%), in part due to the use of inadequately sterilized needles in mass programs to treat endemic schistosomiasis. In developed countries, hepatocellular carcinoma associated with HCV has the fastest growing cancer-related death rate.12

CURRENTLY, FEWER THAN 50% OF PATIENTS ARE CURED

The goal of HCV treatment is to eradicate the virus. However, most infected patients (especially in the United States and Europe) are infected with HCV genotype 1, which is the most difficult genotype to treat.

Successful treatment of HCV is defined as achieving a sustained virologic response—ie, the absence of detectable HCV RNA in the serum 24 weeks after completion of therapy. Once a sustained virologic response is achieved, lifetime “cure” of HCV infection is expected in more than 99% of patients.13

The current standard therapy for HCV, pegylated interferon plus ribavirin for 48 weeks, is effective in only 40% to 50% of patients with genotype 1 infection.14 Therefore, assessing predictors of response before starting treatment can help select patients who are most likely to benefit from therapy.

Viral factors associated with a sustained virologic response include HCV genotypes other than genotype 1 and a low baseline viral load.

Beneficial patient-related factors include younger age, nonblack ethnicity, low body weight (≤ 75 kg), low body mass index, absence of insulin resistance, and absence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

More recently, a single-nucleotide polymorphism near the interleukin 28B (IL28B) gene, coding for interferon lambda 3, was found to be associated with a twofold difference in the rates of sustained virologic response: patients with the favorable genotype CC were two times more likely to achieve a sustained virologic response than patients with the CT or TT genotypes.15–17

PROTEASE INHIBITORS: MECHANISM OF ACTION

NS3/4A protease inhibitors rely on the principle of end-product inhibition, in which the cleavage product of the protease (a peptide) acts to inhibit the enzyme activity; this is why they are called peptidomimetics. The active site of the NS3/4A protease is a shallow groove composed of three highly conserved amino acid residues, which may explain why protease inhibitors display high antiviral efficacy but pose a low barrier to the development of resistance.20

Protease inhibitors are prone to resistance

The development of viral resistance to protease inhibitors has been a major drawback to their use in patients with chronic HCV infection.21

HCV is a highly variable virus with many genetically distinct but closely related quasispecies circulating in the blood at any given time. Drug-resistant, mutated variants preexist within the patient’s quasispecies, but only in small quantities because of their lesser replication fitness compared with the wild-type virus.22 When direct-acting antiviral therapy is started, the quantity of the wild-type virus decreases and the mutated virus gains replication fitness. Using protease inhibitors as monotherapy selects resistant viral populations rapidly within a few days or weeks.

HCV subtypes 1a and 1b may have different resistance profiles. With genotype 1a, some resistance-associated amino acid substitutions require only one nucleotide change, but with genotype 1b, two nucleotide changes are needed, making resistance less frequent in patients with HCV genotype 1b.23

BOCEPREVIR

Boceprevir is a specific inhibitor of the HCV viral protease NS3/4A.

In phase 3 clinical trials, boceprevir 800 mg three times a day was used with pegylated interferon alfa-2b (PegIntron) 1.5 μg/kg/week and ribavirin (Rebetol) 600 to 1,400 mg daily according to body weight.

Before patients started taking boceprevir, they went through a 4-week lead-in phase, during which they received pegylated interferon and ribavirin. This schedule appeared to reduce the incidence of viral breakthrough in phase 2 trials, and it produced higher rates of sustained virologic response and lower relapse rates compared with triple therapy without a lead-in phase.

Rapid virologic response was defined as undetectable HCV RNA at week 4 of boceprevir therapy (week 8 of the whole regimen).

Boceprevir in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1: The SPRINT-2 trial

The Serine Protease Inhibitor Therapy 2 (SPRINT-2) trial1 included more than 1,000 previously untreated adults with HCV genotype 1 infection (938 nonblack patients and 159 black patients; two other nonblack patients did not receive any study drug and were not included in the analysis). In this double-blind trial, patients were randomized into three groups:

- The control group received the standard of care with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks

- The response-guided therapy group received boceprevir plus pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 24 weeks after the 4-week lead-in phase; if HCV RNA was undetectable from week 8 to week 24, treatment was considered complete, but if HCV RNA was detectable at any point from week 8 to week 24, pegylated interferon and ribavirin were continued for a total of 48 weeks.

- The fixed-duration therapy group received boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 44 weeks after the lead-in period.

The rate of relapse was 8% and 9% in the boceprevir groups vs 23% in the control group. Patients in the boceprevir groups who had a decrease in HCV RNA of less than 1 log10 during the lead-in phase were found to have a significantly higher rate of boceprevirresistant variants than those who achieved a decrease of HCV RNA of 1 log10 or more.

Boceprevir in previously treated patients with HCV genotype 1: The RESPOND-2 trial

The Retreatment With HCV Serine Protease Inhibitor Boceprevir and PegIntron/Rebetol 2) (RESPOND-2) trial2 was designed to assess the efficacy of combined boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for repeat treatment of patients with HCV genotype 1. These patients had previously undergone standard treatment and had a reduction of 2 log10 or more in HCV RNA after 12 weeks of therapy but with detectable HCV RNA during the therapy period or had had a relapse (defined as undetectable HCV RNA at the end of a previous course of therapy with HCV RNA positivity thereafter). Importantly, null-responders (those who had a reduction of less than 2 log10 in HCV RNA after 12 weeks of therapy) were excluded from this trial.

After a lead-in period of interferon-ribavirin treatment for 4 weeks, 403 patients were assigned to one of three treatment groups:

- Pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 44 weeks (the control group)

- Boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin in a response-guided regimen

- Boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 44 weeks (the fixed-duration group).

Sustained virologic response was achieved in only 21% of patients in the control group. Adding boceprevir increased the rate to 59% in the response-guided therapy group and to 67% in the fixed-duration group. Previous relapsers had better rates than partial responders (69%–75% vs 40%–52%).

Importantly, patients who had a poor response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin during the lead-in phase (defined as having less than a 1-log decrease in the virus before starting boceprevir) had significantly lower rates of sustained virologic response and higher rates of resistance-associated virus variants.

Side effects of boceprevir

Overall, boceprevir is well tolerated. The most common side effects of triple therapy are those usually seen with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, such as flulike symptoms and fatigue (Table 2). However, anemia was more frequent in the boceprevir groups in both SPRINT-2 and RESPOND-2 (45%–50% compared with 20%–29% in the control groups). Erythropoietin was allowed in these studies and was used in about 40% of patients.

The other common side effect associated with boceprevir was dysgeusia (alteration of taste). Dysgeusia was reported by approximately 40% of patients; however, most dysgeusia events were mild to moderate in intensity and did not lead to treatment cessation.

In the SPRINT-2 trial,1 the study drugs had to be discontinued in 12% to 16% of patients in the boceprevir groups because of adverse events, which was similar to the rate (16%) in the control group. Erythropoietin was allowed in this trial, and it was used in 43% of patients in the boceprevir groups compared with 24% in the control group, with discontinuation owing to anemia occurring in 2% and 1% of cases, respectively.

TELAPREVIR

Telaprevir, the other protease NS3/4A inhibitor, has also shown efficacy over current standard therapy in phase 3 clinical trials. It was used in a dose of 750 mg three times a day with pegylated interferon alfa-2a (Pegasys) 180 μg per week and ribavirin (Copegus) 1,000 to 1,200 mg daily according to body weight. A lead-in phase with pegylated interferon and ribavirin was not applied with telaprevir, as it was in the boceprevir trials. Extended rapid virologic response was defined as an undetectable HCV RNA at weeks 4 and 12 of therapy.

Telaprevir in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1

The ADVANCE study3 was a double-blind randomized trial assessing the efficacy and safety of telaprevir in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in more than 1,000 previously untreated patients. The three treatment groups received:

- Telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 8 weeks, followed by pegylated interferon and ribavirin alone for 16 weeks in patients who achieved an extended rapid virologic response (total duration of 24 weeks) or 40 weeks in patients who did not (total duration of 48 weeks)

- Telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 12 weeks, followed by pegylated interferon-ribavirin alone for 12 (total of 24 weeks) or 36 weeks (total of 48 weeks) according to extended rapid virologic response

- Standard care with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks.

The rate of sustained virologic response was 69% in the group that received telaprevir for 8 weeks and 75% in the group that received it for 12 weeks compared with 44% in the control group (P < .0001 for both) (Table 2). Patients infected with HCV genotype 1b had a higher sustained virologic response rate (79%) than those infected with HCV genotype 1a (71%).

Sustained virologic response rates were lower in black patients and patients with bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis, but were still significantly higher in the telaprevir groups than in the control group. The results of this subset analysis were limited by small numbers of patients in each category.

In total, 57% of those who received telaprevir for 8 weeks and 58% of those who received it for 12 weeks achieved an extended rapid virologic response and were able to cut the duration of their therapy in half (from 48 weeks to 24 weeks).

The relapse rates were 9% in the telaprevir groups and 28% in the control group.

The rate of virologic failure was lower in patients who received triple therapy than in those who received interferon-ribavirin alone (8% in the group that got telaprevir for 12 weeks and 13% in the group that got it for 8 weeks, vs 32% in the control group). The failure rate was also lower in patients with HCV genotype 1b infection than in those with genotype 1a.

The ILLUMINATE study4 (Illustrating the Effects of Combination Therapy With Telaprevir) investigated whether longer duration of treatment than that given in the ADVANCE trial increased the rate of sustained virologic response. Previously untreated patients received telaprevir, interferon, and ribavirin for 12 weeks, and those who achieved an extended rapid virologic response were randomized at week 20 to continue interferonribavirin treatment for 24 or 48 weeks of total treatment.

The sustained virologic response rates in patients who achieved an extended rapid virologic response were 92% in the group that received pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks, and 88% in those who received it for 48 weeks. Thus, the results of this study support the use of response-guided therapy for telaprevir-based regimens.

Telaprevir in previously treated patients with HCV genotype 1: The REALIZE trial

In this phase 3 placebo-controlled trial,5 622 patients with prior relapse, partial response, or null response were randomly allocated into one of three groups:

- Telaprevir for 12 weeks plus pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks

- Lead-in for 4 weeks followed by 12 weeks of triple therapy and another 32 weeks of pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks (the control group).

The overall sustained virologic response rates were 66% and 64%, respectively, in the telaprevir groups vs 17% in the control group (P < .0001). The sustained virologic response rates in the telaprevir groups were 83% to 88% in prior relapsers, 54% to 59% in partial responders, and 29% to 33% in null-responders. Of note, patients did not benefit from the lead-in phase.

This was the only trial to investigate the response to triple therapy in null-responders, a group in which treatment has been considered hopeless. A response rate of approximately 31% was encouraging, especially if we compare it with the 5% response rate achieved with the current standard of care with pegylated interferon and ribavirin.

Telaprevir side effects

As with boceprevir-based triple therapy, the most common adverse events were related to pegylated interferon (Table 2).

Nearly 50% of patients who receive telaprevir develop a skin rash that is primarily eczematous, can be managed with topical steroids, and usually resolves when telaprevir is discontinued. Severe rashes occurred in 3% to 6% of patients in the ADVANCE trial,3 and three suspected cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported to the FDA.

Other side effects that were more frequent with telaprevir included pruritus, nausea, diarrhea, and anemia. On average, the hemoglobin level decreased by an additional 1 g/dL in the telaprevir treatment groups compared with the groups that received only pegylated interferon-ribavirin. Erythropoietin use was not allowed in the phase 3 telaprevir studies, and anemia was managed by ribavirin dose reduction.

In the ADVANCE trial,3 study drugs were discontinued owing to adverse events in 7% to 8% of the patients in the telaprevir groups compared with 4% in the control group. In the ILLUMINATE trial,4 17% of patients had to permanently discontinue all study drugs due to adverse events.

FDA-APPROVED TREATMENT REGIMENS FOR BOCEPREVIR AND TELAPREVIR

For treatment algorithms, see the eFigures that accompany this article online.

Boceprevir in previously untreated patients

- Week 0—Start pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 4—Add boceprevir

- Week 8—Measure HCV RNA

- Week 12—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is more than 100 IU/mL

- Week 24—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is detectable

- Week 28—Stop all treatment if HCV RNA was undetectable at weeks 8 and 24

- Week 36—Measure HCV RNA; stop boceprevir

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 1).

Boceprevir in previously treated patients

- Week 0—Start pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 4—Add boceprevir

- Week 8—Measure HCV RNA

- Week 12—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is more than 100 IU/mL

- Week 24—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is detectable

- Week 36—if HCV RNA was not detectable at week 8, stop all treatment now; if HCV RNA was detectable at week 8, stop boceprevir now but continue pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 2).

Telaprevir in previously untreated patients and prior relapsers

- Week 0—start telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin

- Week 4—measure HCV RNA; stop all treatment if it is more than 1,000 IU/mL

- Week 12—Stop telaprevir; measure HCV RNA; stop all treatment if HCV RNA is more than 1,000 IU/mL

- Week 24—Stop pegylated interferon and ribavirin if HCV RNA was undetectable at week 12; measure HCV RNA and stop treatment if it is detectable; otherwise, continue pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 3).

Telaprevir in patients who previously achieved a partial or null response

- Week 0—Start telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin

- Week 4—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is more than 1,000 IU/mL

- Week 12—Measure HCV RNA; stop all treatment if it is more than 1,000 IU/mL; if less than 1,000 IU/mL then stop telaprevir but continue pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 24—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if HCV RNA is detectable

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 4).

Drug interactions with boceprevir and telaprevir

Both boceprevir and telaprevir inhibit cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) and thus are contraindicated in combination with drugs highly dependent on CYP3A for clearance and with drugs for which elevated plasma concentrations are associated with serious adverse events, such as atorvastatin (Lipitor), simvastatin (Zocor), sildenafil (Viagra), midazolam (Versed), and St. John’s wort. Giving potent inducers of CYP3A with boceprevir or telaprevir may lead to lower exposure and loss of efficacy of both protease inhibitors.

EMERGING THERAPIES FOR HCV

Thanks to a better understanding of the biology of HCV infection, the effort to develop new therapeutic agents started to focus on targeting specific steps of the viral life cycle, including attachment, entry into cells, replication, and release.24

Currently, more than 50 clinical trials are evaluating new direct-acting antivirals to treat HCV infection.25 Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies that target the molecular process involved in HCV attachment and entry are being developed.26 The nonstructural protein NS5B (RNA polymerase) is intimately involved in viral replication and represents a promising target.27 Several nucleosides and nonnucleoside protease inhibitors have already entered clinical trials.

The low fidelity of the HCV replication machinery leads to a very high mutation rate, thus enabling the virus to quickly develop mutations that resist agents targeting viral enzymes.28 Therefore, a novel approach is to target host cofactors that are essential for HCV replication. An intriguing study by Lanford et al29 demonstrated that antagonizing microRNA-122 (the most abundant microRNA in the liver and an essential cofactor for viral RNA replication) by the oligonucleotide SPC3649 caused marked and prolonged reduction of HCV viremia in chronically infected chimpanzees.29

Although we are still in the early stages of drug development, the future holds great promise for newer drugs to improve the sustained virologic response, shorten the duration of treatment, improve tolerability with interferon-sparing regimens, and decrease viral resistance.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

With the introduction of the first direct-acting antiviral medications for HCV (boceprevir and telaprevir), 2011 will be marked as the year that changed hepatitis C treatment for the better. Triple therapy with pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and either boceprevir or telaprevir has the potential for increasing the rate of sustained virologic response to around 70% in previously untreated patients and 65% in previously treated patients who are infected with HCV genotype 1. The IL28B polymorphisms appear to play a role in the rate of sustained virologic response achieved with triple therapy, with preliminary data showing a better response rate in patients who have the CC genotype.17

These drugs will add up to $50,000 to the cost of treating hepatitis C virus infection, depending on the drug used and the length of treatment. However, they may be well worth it if they prevent liver failure and the need for transplantation.

Many questions remain, such as how to use these new regimens to treat special patient populations—for example, those with a recurrence of HCV infection after liver transplantation, those co-infected with HCV and human immunodeficiency virus, and those infected with HCV genotypes other than genotype 1.

Other direct-acting antiviral agents that specifically target the replication cycle of HCV are currently in clinical development. In fact, the future has already started with the release of the Interferon-Free Regimen for the Management of HCV (INFORM-1) study results.30 This was the first trial to evaluate an interferon-free regimen for patients with chronic HCV infection using two direct-acting antiviral drugs (the protease inhibitor danoprevir and the polymerase inhibitor RG7128), with promising results.

The treatment of hepatitis c virus (HCV) infection is on the brink of major changes with the recent approval of the first direct-acting antiviral agents, the protease inhibitors boceprevir (Victrelis) and telaprevir (Incivek).

Both drugs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Advisory Panel for Chronic Hepatitis C in May 2011 and are believed to significantly improve treatment outcomes for patients with HCV genotype 1 infection.

A MAJOR PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM

HCV infection is a major public health problem. Nearly 4 million people in the United States are infected.6,7 Most patients with acute HCV infection become chronically infected, and up to 25% eventually develop cirrhosis and its complications, making HCV infection the leading indication for liver transplantation.8–10

Chronic HCV infection has a large global impact, with 180 million people affected across all economic and social groups.11 The highest prevalence of HCV has been reported in Egypt (14%), in part due to the use of inadequately sterilized needles in mass programs to treat endemic schistosomiasis. In developed countries, hepatocellular carcinoma associated with HCV has the fastest growing cancer-related death rate.12

CURRENTLY, FEWER THAN 50% OF PATIENTS ARE CURED

The goal of HCV treatment is to eradicate the virus. However, most infected patients (especially in the United States and Europe) are infected with HCV genotype 1, which is the most difficult genotype to treat.

Successful treatment of HCV is defined as achieving a sustained virologic response—ie, the absence of detectable HCV RNA in the serum 24 weeks after completion of therapy. Once a sustained virologic response is achieved, lifetime “cure” of HCV infection is expected in more than 99% of patients.13

The current standard therapy for HCV, pegylated interferon plus ribavirin for 48 weeks, is effective in only 40% to 50% of patients with genotype 1 infection.14 Therefore, assessing predictors of response before starting treatment can help select patients who are most likely to benefit from therapy.

Viral factors associated with a sustained virologic response include HCV genotypes other than genotype 1 and a low baseline viral load.

Beneficial patient-related factors include younger age, nonblack ethnicity, low body weight (≤ 75 kg), low body mass index, absence of insulin resistance, and absence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

More recently, a single-nucleotide polymorphism near the interleukin 28B (IL28B) gene, coding for interferon lambda 3, was found to be associated with a twofold difference in the rates of sustained virologic response: patients with the favorable genotype CC were two times more likely to achieve a sustained virologic response than patients with the CT or TT genotypes.15–17

PROTEASE INHIBITORS: MECHANISM OF ACTION

NS3/4A protease inhibitors rely on the principle of end-product inhibition, in which the cleavage product of the protease (a peptide) acts to inhibit the enzyme activity; this is why they are called peptidomimetics. The active site of the NS3/4A protease is a shallow groove composed of three highly conserved amino acid residues, which may explain why protease inhibitors display high antiviral efficacy but pose a low barrier to the development of resistance.20

Protease inhibitors are prone to resistance

The development of viral resistance to protease inhibitors has been a major drawback to their use in patients with chronic HCV infection.21

HCV is a highly variable virus with many genetically distinct but closely related quasispecies circulating in the blood at any given time. Drug-resistant, mutated variants preexist within the patient’s quasispecies, but only in small quantities because of their lesser replication fitness compared with the wild-type virus.22 When direct-acting antiviral therapy is started, the quantity of the wild-type virus decreases and the mutated virus gains replication fitness. Using protease inhibitors as monotherapy selects resistant viral populations rapidly within a few days or weeks.

HCV subtypes 1a and 1b may have different resistance profiles. With genotype 1a, some resistance-associated amino acid substitutions require only one nucleotide change, but with genotype 1b, two nucleotide changes are needed, making resistance less frequent in patients with HCV genotype 1b.23

BOCEPREVIR

Boceprevir is a specific inhibitor of the HCV viral protease NS3/4A.

In phase 3 clinical trials, boceprevir 800 mg three times a day was used with pegylated interferon alfa-2b (PegIntron) 1.5 μg/kg/week and ribavirin (Rebetol) 600 to 1,400 mg daily according to body weight.

Before patients started taking boceprevir, they went through a 4-week lead-in phase, during which they received pegylated interferon and ribavirin. This schedule appeared to reduce the incidence of viral breakthrough in phase 2 trials, and it produced higher rates of sustained virologic response and lower relapse rates compared with triple therapy without a lead-in phase.

Rapid virologic response was defined as undetectable HCV RNA at week 4 of boceprevir therapy (week 8 of the whole regimen).

Boceprevir in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1: The SPRINT-2 trial

The Serine Protease Inhibitor Therapy 2 (SPRINT-2) trial1 included more than 1,000 previously untreated adults with HCV genotype 1 infection (938 nonblack patients and 159 black patients; two other nonblack patients did not receive any study drug and were not included in the analysis). In this double-blind trial, patients were randomized into three groups:

- The control group received the standard of care with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks

- The response-guided therapy group received boceprevir plus pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 24 weeks after the 4-week lead-in phase; if HCV RNA was undetectable from week 8 to week 24, treatment was considered complete, but if HCV RNA was detectable at any point from week 8 to week 24, pegylated interferon and ribavirin were continued for a total of 48 weeks.

- The fixed-duration therapy group received boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 44 weeks after the lead-in period.

The rate of relapse was 8% and 9% in the boceprevir groups vs 23% in the control group. Patients in the boceprevir groups who had a decrease in HCV RNA of less than 1 log10 during the lead-in phase were found to have a significantly higher rate of boceprevirresistant variants than those who achieved a decrease of HCV RNA of 1 log10 or more.

Boceprevir in previously treated patients with HCV genotype 1: The RESPOND-2 trial

The Retreatment With HCV Serine Protease Inhibitor Boceprevir and PegIntron/Rebetol 2) (RESPOND-2) trial2 was designed to assess the efficacy of combined boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for repeat treatment of patients with HCV genotype 1. These patients had previously undergone standard treatment and had a reduction of 2 log10 or more in HCV RNA after 12 weeks of therapy but with detectable HCV RNA during the therapy period or had had a relapse (defined as undetectable HCV RNA at the end of a previous course of therapy with HCV RNA positivity thereafter). Importantly, null-responders (those who had a reduction of less than 2 log10 in HCV RNA after 12 weeks of therapy) were excluded from this trial.

After a lead-in period of interferon-ribavirin treatment for 4 weeks, 403 patients were assigned to one of three treatment groups:

- Pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 44 weeks (the control group)

- Boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin in a response-guided regimen

- Boceprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 44 weeks (the fixed-duration group).

Sustained virologic response was achieved in only 21% of patients in the control group. Adding boceprevir increased the rate to 59% in the response-guided therapy group and to 67% in the fixed-duration group. Previous relapsers had better rates than partial responders (69%–75% vs 40%–52%).

Importantly, patients who had a poor response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin during the lead-in phase (defined as having less than a 1-log decrease in the virus before starting boceprevir) had significantly lower rates of sustained virologic response and higher rates of resistance-associated virus variants.

Side effects of boceprevir

Overall, boceprevir is well tolerated. The most common side effects of triple therapy are those usually seen with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, such as flulike symptoms and fatigue (Table 2). However, anemia was more frequent in the boceprevir groups in both SPRINT-2 and RESPOND-2 (45%–50% compared with 20%–29% in the control groups). Erythropoietin was allowed in these studies and was used in about 40% of patients.

The other common side effect associated with boceprevir was dysgeusia (alteration of taste). Dysgeusia was reported by approximately 40% of patients; however, most dysgeusia events were mild to moderate in intensity and did not lead to treatment cessation.

In the SPRINT-2 trial,1 the study drugs had to be discontinued in 12% to 16% of patients in the boceprevir groups because of adverse events, which was similar to the rate (16%) in the control group. Erythropoietin was allowed in this trial, and it was used in 43% of patients in the boceprevir groups compared with 24% in the control group, with discontinuation owing to anemia occurring in 2% and 1% of cases, respectively.

TELAPREVIR

Telaprevir, the other protease NS3/4A inhibitor, has also shown efficacy over current standard therapy in phase 3 clinical trials. It was used in a dose of 750 mg three times a day with pegylated interferon alfa-2a (Pegasys) 180 μg per week and ribavirin (Copegus) 1,000 to 1,200 mg daily according to body weight. A lead-in phase with pegylated interferon and ribavirin was not applied with telaprevir, as it was in the boceprevir trials. Extended rapid virologic response was defined as an undetectable HCV RNA at weeks 4 and 12 of therapy.

Telaprevir in previously untreated patients with HCV genotype 1

The ADVANCE study3 was a double-blind randomized trial assessing the efficacy and safety of telaprevir in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in more than 1,000 previously untreated patients. The three treatment groups received:

- Telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 8 weeks, followed by pegylated interferon and ribavirin alone for 16 weeks in patients who achieved an extended rapid virologic response (total duration of 24 weeks) or 40 weeks in patients who did not (total duration of 48 weeks)

- Telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin for 12 weeks, followed by pegylated interferon-ribavirin alone for 12 (total of 24 weeks) or 36 weeks (total of 48 weeks) according to extended rapid virologic response

- Standard care with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks.

The rate of sustained virologic response was 69% in the group that received telaprevir for 8 weeks and 75% in the group that received it for 12 weeks compared with 44% in the control group (P < .0001 for both) (Table 2). Patients infected with HCV genotype 1b had a higher sustained virologic response rate (79%) than those infected with HCV genotype 1a (71%).

Sustained virologic response rates were lower in black patients and patients with bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis, but were still significantly higher in the telaprevir groups than in the control group. The results of this subset analysis were limited by small numbers of patients in each category.

In total, 57% of those who received telaprevir for 8 weeks and 58% of those who received it for 12 weeks achieved an extended rapid virologic response and were able to cut the duration of their therapy in half (from 48 weeks to 24 weeks).

The relapse rates were 9% in the telaprevir groups and 28% in the control group.

The rate of virologic failure was lower in patients who received triple therapy than in those who received interferon-ribavirin alone (8% in the group that got telaprevir for 12 weeks and 13% in the group that got it for 8 weeks, vs 32% in the control group). The failure rate was also lower in patients with HCV genotype 1b infection than in those with genotype 1a.

The ILLUMINATE study4 (Illustrating the Effects of Combination Therapy With Telaprevir) investigated whether longer duration of treatment than that given in the ADVANCE trial increased the rate of sustained virologic response. Previously untreated patients received telaprevir, interferon, and ribavirin for 12 weeks, and those who achieved an extended rapid virologic response were randomized at week 20 to continue interferonribavirin treatment for 24 or 48 weeks of total treatment.

The sustained virologic response rates in patients who achieved an extended rapid virologic response were 92% in the group that received pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks, and 88% in those who received it for 48 weeks. Thus, the results of this study support the use of response-guided therapy for telaprevir-based regimens.

Telaprevir in previously treated patients with HCV genotype 1: The REALIZE trial

In this phase 3 placebo-controlled trial,5 622 patients with prior relapse, partial response, or null response were randomly allocated into one of three groups:

- Telaprevir for 12 weeks plus pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks

- Lead-in for 4 weeks followed by 12 weeks of triple therapy and another 32 weeks of pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 weeks (the control group).

The overall sustained virologic response rates were 66% and 64%, respectively, in the telaprevir groups vs 17% in the control group (P < .0001). The sustained virologic response rates in the telaprevir groups were 83% to 88% in prior relapsers, 54% to 59% in partial responders, and 29% to 33% in null-responders. Of note, patients did not benefit from the lead-in phase.

This was the only trial to investigate the response to triple therapy in null-responders, a group in which treatment has been considered hopeless. A response rate of approximately 31% was encouraging, especially if we compare it with the 5% response rate achieved with the current standard of care with pegylated interferon and ribavirin.

Telaprevir side effects

As with boceprevir-based triple therapy, the most common adverse events were related to pegylated interferon (Table 2).

Nearly 50% of patients who receive telaprevir develop a skin rash that is primarily eczematous, can be managed with topical steroids, and usually resolves when telaprevir is discontinued. Severe rashes occurred in 3% to 6% of patients in the ADVANCE trial,3 and three suspected cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported to the FDA.

Other side effects that were more frequent with telaprevir included pruritus, nausea, diarrhea, and anemia. On average, the hemoglobin level decreased by an additional 1 g/dL in the telaprevir treatment groups compared with the groups that received only pegylated interferon-ribavirin. Erythropoietin use was not allowed in the phase 3 telaprevir studies, and anemia was managed by ribavirin dose reduction.

In the ADVANCE trial,3 study drugs were discontinued owing to adverse events in 7% to 8% of the patients in the telaprevir groups compared with 4% in the control group. In the ILLUMINATE trial,4 17% of patients had to permanently discontinue all study drugs due to adverse events.

FDA-APPROVED TREATMENT REGIMENS FOR BOCEPREVIR AND TELAPREVIR

For treatment algorithms, see the eFigures that accompany this article online.

Boceprevir in previously untreated patients

- Week 0—Start pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 4—Add boceprevir

- Week 8—Measure HCV RNA

- Week 12—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is more than 100 IU/mL

- Week 24—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is detectable

- Week 28—Stop all treatment if HCV RNA was undetectable at weeks 8 and 24

- Week 36—Measure HCV RNA; stop boceprevir

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 1).

Boceprevir in previously treated patients

- Week 0—Start pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 4—Add boceprevir

- Week 8—Measure HCV RNA

- Week 12—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is more than 100 IU/mL

- Week 24—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is detectable

- Week 36—if HCV RNA was not detectable at week 8, stop all treatment now; if HCV RNA was detectable at week 8, stop boceprevir now but continue pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 2).

Telaprevir in previously untreated patients and prior relapsers

- Week 0—start telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin

- Week 4—measure HCV RNA; stop all treatment if it is more than 1,000 IU/mL

- Week 12—Stop telaprevir; measure HCV RNA; stop all treatment if HCV RNA is more than 1,000 IU/mL

- Week 24—Stop pegylated interferon and ribavirin if HCV RNA was undetectable at week 12; measure HCV RNA and stop treatment if it is detectable; otherwise, continue pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 3).

Telaprevir in patients who previously achieved a partial or null response

- Week 0—Start telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin

- Week 4—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if it is more than 1,000 IU/mL

- Week 12—Measure HCV RNA; stop all treatment if it is more than 1,000 IU/mL; if less than 1,000 IU/mL then stop telaprevir but continue pegylated interferon and ribavirin

- Week 24—Measure HCV RNA; stop treatment if HCV RNA is detectable

- Week 48—Stop all treatment (eFigure 4).

Drug interactions with boceprevir and telaprevir

Both boceprevir and telaprevir inhibit cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) and thus are contraindicated in combination with drugs highly dependent on CYP3A for clearance and with drugs for which elevated plasma concentrations are associated with serious adverse events, such as atorvastatin (Lipitor), simvastatin (Zocor), sildenafil (Viagra), midazolam (Versed), and St. John’s wort. Giving potent inducers of CYP3A with boceprevir or telaprevir may lead to lower exposure and loss of efficacy of both protease inhibitors.

EMERGING THERAPIES FOR HCV

Thanks to a better understanding of the biology of HCV infection, the effort to develop new therapeutic agents started to focus on targeting specific steps of the viral life cycle, including attachment, entry into cells, replication, and release.24

Currently, more than 50 clinical trials are evaluating new direct-acting antivirals to treat HCV infection.25 Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies that target the molecular process involved in HCV attachment and entry are being developed.26 The nonstructural protein NS5B (RNA polymerase) is intimately involved in viral replication and represents a promising target.27 Several nucleosides and nonnucleoside protease inhibitors have already entered clinical trials.

The low fidelity of the HCV replication machinery leads to a very high mutation rate, thus enabling the virus to quickly develop mutations that resist agents targeting viral enzymes.28 Therefore, a novel approach is to target host cofactors that are essential for HCV replication. An intriguing study by Lanford et al29 demonstrated that antagonizing microRNA-122 (the most abundant microRNA in the liver and an essential cofactor for viral RNA replication) by the oligonucleotide SPC3649 caused marked and prolonged reduction of HCV viremia in chronically infected chimpanzees.29

Although we are still in the early stages of drug development, the future holds great promise for newer drugs to improve the sustained virologic response, shorten the duration of treatment, improve tolerability with interferon-sparing regimens, and decrease viral resistance.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

With the introduction of the first direct-acting antiviral medications for HCV (boceprevir and telaprevir), 2011 will be marked as the year that changed hepatitis C treatment for the better. Triple therapy with pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and either boceprevir or telaprevir has the potential for increasing the rate of sustained virologic response to around 70% in previously untreated patients and 65% in previously treated patients who are infected with HCV genotype 1. The IL28B polymorphisms appear to play a role in the rate of sustained virologic response achieved with triple therapy, with preliminary data showing a better response rate in patients who have the CC genotype.17

These drugs will add up to $50,000 to the cost of treating hepatitis C virus infection, depending on the drug used and the length of treatment. However, they may be well worth it if they prevent liver failure and the need for transplantation.

Many questions remain, such as how to use these new regimens to treat special patient populations—for example, those with a recurrence of HCV infection after liver transplantation, those co-infected with HCV and human immunodeficiency virus, and those infected with HCV genotypes other than genotype 1.

Other direct-acting antiviral agents that specifically target the replication cycle of HCV are currently in clinical development. In fact, the future has already started with the release of the Interferon-Free Regimen for the Management of HCV (INFORM-1) study results.30 This was the first trial to evaluate an interferon-free regimen for patients with chronic HCV infection using two direct-acting antiviral drugs (the protease inhibitor danoprevir and the polymerase inhibitor RG7128), with promising results.

- Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1195–1206.

- Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1207–1217.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; for the ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2405–2416.

- Sherman KE, Flamm SL, Afdhal NH, et al; for the ILLUMINATE Study Team. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1014–1024.

- Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, et al; for the REALIZE Study Team. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2417–2428.

- Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:705–714.

- Mitchell AE, Colvin HM, Palmer Beasley R. Institute of Medicine recommendations for the prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Hepatology 2010; 51:729–733.

- Kim WR. The burden of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology 2002; 36:S30–S34.

- Marcellin P, Asselah T, Boyer N. Fibrosis and disease progression in hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 36:S47–S56.

- Seeff LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 36:S35–S46.

- Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int 2009; 29(suppl 1):74–81.

- National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of hepatitis C: 2002—June 10–12, 2002. Hepatology 2002; 36:S3–S20.

- Pearlman BL, Traub N. Sustained virologic response to antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a cure and so much more. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:889–900.

- Hoofnagle JH, Seeff LB. Peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2444–2451.

- Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 2009; 461:399–401.

- Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet 2009; 41:1100–1104.

- Thompson AJ, Muir AJ, Sulkowski MS, et al. Interleukin-28B polymorphism improves viral kinetics and is the strongest pretreatment predictor of sustained virologic response in genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology 2010; 139:120–129.e118.

- Nielsen SU, Bassendine MF, Burt AD, Bevitt DJ, Toms GL. Characterization of the genome and structural proteins of hepatitis C virus resolved from infected human liver. J Gen Virol 2004; 85:1497–1507.

- Penin F, Dubuisson J, Rey FA, Moradpour D, Pawlotsky JM. Structural biology of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2004; 39:5–19.

- Nelson DR. The role of triple therapy with protease inhibitors in hepatitis C virus genotype 1 naive patients. Liver Int 2011; 31(suppl 1):53–57.

- Pawlotsky JM. Treatment failure and resistance with direct-acting antiviral drugs against hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2011; 53:1742–1751.

- Monto A, Schooley RT, Lai JC, et al. Lessons from HIV therapy applied to viral hepatitis therapy: summary of a workshop. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105:989–1004.

- McCown MF, Rajyaguru S, Kular S, Cammack N, Najera I. GT-1a or GT-1b subtype-specific resistance profiles for hepatitis C virus inhibitors telaprevir and HCV-796. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:2129–2132.

- Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV. Review article: novel therapeutic options for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 27:866–884.

- Naggie S, Patel K, McHutchison J. Hepatitis C virus directly acting antivirals: current developments with NS3/4A HCV serine protease inhibitors. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65:2063–2069.

- Mir HM, Birerdinc A, Younossi ZM. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against the HCV envelope proteins. Clin Liver Dis 2009; 13:477–486.

- Birerdinc A, Younossi ZM. Emerging therapies for hepatitis C virus. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2010; 15:535–544.

- Khattab MA. Targeting host factors: a novel rationale for the management of hepatitis C virus. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:3472–3479.

- Lanford RE, Hildebrandt-Eriksen ES, Petri A, et al. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science 2010; 327:198–201.

- Gane EJ, Roberts SK, Stedman CA, et al. Oral combination therapy with a nucleoside polymerase inhibitor (RG7128) and danoprevir for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection (INFORM-1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2010; 376:1467–1475.

- Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1195–1206.

- Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1207–1217.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; for the ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2405–2416.

- Sherman KE, Flamm SL, Afdhal NH, et al; for the ILLUMINATE Study Team. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1014–1024.

- Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, et al; for the REALIZE Study Team. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2417–2428.

- Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:705–714.

- Mitchell AE, Colvin HM, Palmer Beasley R. Institute of Medicine recommendations for the prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Hepatology 2010; 51:729–733.

- Kim WR. The burden of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology 2002; 36:S30–S34.

- Marcellin P, Asselah T, Boyer N. Fibrosis and disease progression in hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 36:S47–S56.

- Seeff LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002; 36:S35–S46.

- Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int 2009; 29(suppl 1):74–81.

- National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of hepatitis C: 2002—June 10–12, 2002. Hepatology 2002; 36:S3–S20.

- Pearlman BL, Traub N. Sustained virologic response to antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a cure and so much more. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:889–900.

- Hoofnagle JH, Seeff LB. Peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2444–2451.

- Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 2009; 461:399–401.

- Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet 2009; 41:1100–1104.

- Thompson AJ, Muir AJ, Sulkowski MS, et al. Interleukin-28B polymorphism improves viral kinetics and is the strongest pretreatment predictor of sustained virologic response in genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology 2010; 139:120–129.e118.

- Nielsen SU, Bassendine MF, Burt AD, Bevitt DJ, Toms GL. Characterization of the genome and structural proteins of hepatitis C virus resolved from infected human liver. J Gen Virol 2004; 85:1497–1507.

- Penin F, Dubuisson J, Rey FA, Moradpour D, Pawlotsky JM. Structural biology of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2004; 39:5–19.

- Nelson DR. The role of triple therapy with protease inhibitors in hepatitis C virus genotype 1 naive patients. Liver Int 2011; 31(suppl 1):53–57.

- Pawlotsky JM. Treatment failure and resistance with direct-acting antiviral drugs against hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2011; 53:1742–1751.

- Monto A, Schooley RT, Lai JC, et al. Lessons from HIV therapy applied to viral hepatitis therapy: summary of a workshop. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105:989–1004.

- McCown MF, Rajyaguru S, Kular S, Cammack N, Najera I. GT-1a or GT-1b subtype-specific resistance profiles for hepatitis C virus inhibitors telaprevir and HCV-796. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:2129–2132.

- Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV. Review article: novel therapeutic options for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 27:866–884.