User login

CASE Bipolar-like symptoms

Mr. R, age 48, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) for the third time in 4 days after a change in his behavior over the last 2.5 weeks. He exhibits heightened extroversion, pressured speech, and uncharacteristic irritability. Mr. R’s wife reports that her husband normally is reserved.

Mr. R’s wife first became concerned when she noticed he was not sleeping and spending his nights changing the locks on their home. Mr. R, who is a business executive, occupied his time by taking notes on ways to protect his identity from the senior partners at his company.

Three weeks before his first ED visit, Mr. R had been treated for a neck abscess with incision and drainage. He was sent home with a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875/125 mg by mouth twice daily. There were no reports of steroid use during or after the procedure. Four days after starting the antibiotic, he stopped taking it because he and his wife felt it was contributing to his mood changes and bizarre behavior.

During his first visit to the ED, Mr. R received a 1-time dose of olanzapine, 5 mg by mouth, which helped temporarily reduce his anxiety; however, he returned the following day with the same anxiety symptoms and was discharged with a 30-day prescription for olanzapine, 5 mg/d, to manage symptoms until he could establish care with an outpatient psychiatrist. Two days later, he returned to the ED yet again convinced people were spying on him and that his coworkers were plotting to have him fired. He was not taking his phone to work due to fears that it would be hacked.

Mr. R’s only home medication is clomiphene citrate, 100 mg/d by mouth, which he’s received for the past 7 months to treat low testosterone. He has no personal or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior signs of mania or hypomania.

At the current ED visit, Mr. R’s testosterone level is checked and is within normal limits. His urine drug screen, head CT, and standard laboratory test results are unremarkable, except for mild transaminitis that does not warrant acute management.

The clinicians in the ED establish a diagnosis of mania, unspecified, and psychotic disorder, unspecified. They recommend that Mr. R be admitted for mood stabilization.

[polldaddy:10485725]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Our initial impression was that Mr. R was experiencing a manic episode from undiagnosed bipolar I disorder. The diagnosis was equivocal considering his age, lack of family history, and absence of prior psychiatric symptoms. In most cases, the mean age of onset for mania is late adolescence to early adulthood. It would be less common for a patient to experience a first manic episode at age 48, although mania may emerge at any age. Results from a large British study showed that the incidence of a first manic episode drops from 13.81% in men age 16 to 25 to 2.62% in men age 46 to 55.1 However, some estimates suggest that the prevalence of late-onset mania is much higher than previously expected; medical comorbidities, such as dementia and delirium, may play a significant role in posing as manic-type symptoms in these patients.2

In Mr. R’s case, he remained fully alert and oriented without waxing and waning attentional deficits, which made delirium less likely. His affective symptoms included a reduced need for sleep, anxiety, irritability, rapid speech, and grandiosity lasting at least 2 weeks. He also exhibited psychotic symptoms in the form of paranoia. Altogether, he fit diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder well.

At the time of his manic episode, Mr. R was taking clomiphene. Clomiphene-induced mania and psychosis has been reported scarcely in the literature.3 In these cases, behavioral changes occurred within the first month of clomiphene initiation, which is dissimilar from Mr. R’s timeline.4 However, there appeared to be a temporal relationship between Mr. R’s use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and his manic episode.

This led us to consider whether medication-induced bipolar disorder would be a more appropriate diagnosis. There are documented associations between mania and antibiotics5; however, to our knowledge, mania secondary specifically to amoxicillin/clavulanate has not been reported extensively in the American literature. We found 1 case of suspected amoxicillin-induced psychosis,6 as well as a case report from the Netherlands of possible amoxicillin/clavulanate-induced mania.7

EVALUATION Ongoing paranoia

During his psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. R remains cooperative and polite, but exhibits ongoing paranoia, pressured speech, and poor reality testing. He remains convinced that “people are out to get me,” and routinely scans the room for safety during daily evaluations. He reports that he feels safe in the hospital, but does not feel safe to leave. Mr. R does not recall if in the past he had taken any products containing amoxicillin, but he is able to appreciate changes in his mood after being prescribed the antibiotic. He reports that starting the antibiotic made him feel confident in social interactions.

Continue to: During Mr. R's psychiatric hospitalization...

During Mr. R’s psychiatric hospitalization, olanzapine is titrated to 10 mg at bedtime. Clomiphene citrate is discontinued to limit any potential precipitants of mania, and amoxicillin/clavulanate is not restarted.

Mr. R gradually shows improvement in sleep quality and duration and becomes less irritable. His speech returns to a regular rate and rhythm. He eventually begins to question whether his fears were reality-based. After 4 days, Mr. R is ready to be discharged home and return to work.

[polldaddy:10485726]

The authors’ observations

The term “antibiomania” is used to describe manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage.8 Clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin are the agents most frequently implicated in antibiomania.9 While numerous reports exist in the literature, antibiomania is still considered a rare or unusual adverse event.

The link between infections and neuropsychiatric symptoms is well documented, which makes it challenging to tease apart the role of the acute infection from the use of antibiotics in precipitating psychiatric symptoms. However, in most reported cases of antibiomania, the onset of manic symptoms typically occurs within the first week of antibiotic initiation and resolves 1 to 3 days after medication discontinuation. The temporal relationship between antibiotic initiation and onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been best highlighted in cases where clarithromycin is used to treat a chronic Helicobacter pylori infection.10

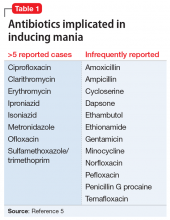

While reports of antibiomania date back more than 6 decades, the exact mechanism by which antibiotics cause psychiatric symptoms is mostly unknown, although there are several hypotheses.5 Many hypotheses suggest some antibiotics play a role in reducing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Quinolones, for example, have been found to cross the blood–brain barrier and can inhibit GABA from binding to the receptor sites. This can result in hyper-excitability in the CNS. Several quinolones have been implicated in antibiomania (Table 15). Penicillins are also thought to interfere with GABA neurotransmission in a similar fashion; however, amoxicillin-clavulanate has poor CNS penetration in the absence of blood–brain barrier disruption,11 which makes this theory a less plausible explanation for Mr. R’s case.

Continue to: Another possible mechanism...

Another possible mechanism of antibiotic-induced CNS excitability is through the glutamatergic system. Cycloserine, an antitubercular agent, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) partial agonist and has reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects.12 It has been proposed that quinolones may also have NMDA agonist activity.

The prostaglandin hypothesis suggests that a decrease in GABA may increase concentrations of steroid hormones in the rat CNS.13 Steroids have been implicated in the breakdown of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).13 A disruption in steroid regulation may prevent PGE1 breakdown. Lithium’s antimanic properties are thought to be caused at least in part by limiting prostaglandin production.14 Thus, a shift in PGE1 may lead to mood dysregulation.

Bipolar disorder has been linked with mitochondrial function abnormalities.15 Antibiotics that target ribosomal RNA may disrupt normal mitochondrial function and increase risk for mania precipitation.15 However, amoxicillin exerts its antibiotic effects through binding to penicillin-binding proteins, which leads to inhibition of the cell wall biosynthesis.

Lastly, research into the microbiome has elucidated the gut-brain axis. In animal studies, the microbiome has been found to play a role in immunity, cognitive function, and behavior. Dysbiosis in the microbiome is currently being investigated for its role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.16 Both the microbiome and changes in mitochondrial function are thought to develop over time, so while these are plausible explanations, an onset within 4 days of antibiotic initiation is likely too short of an exposure time to produce these changes.

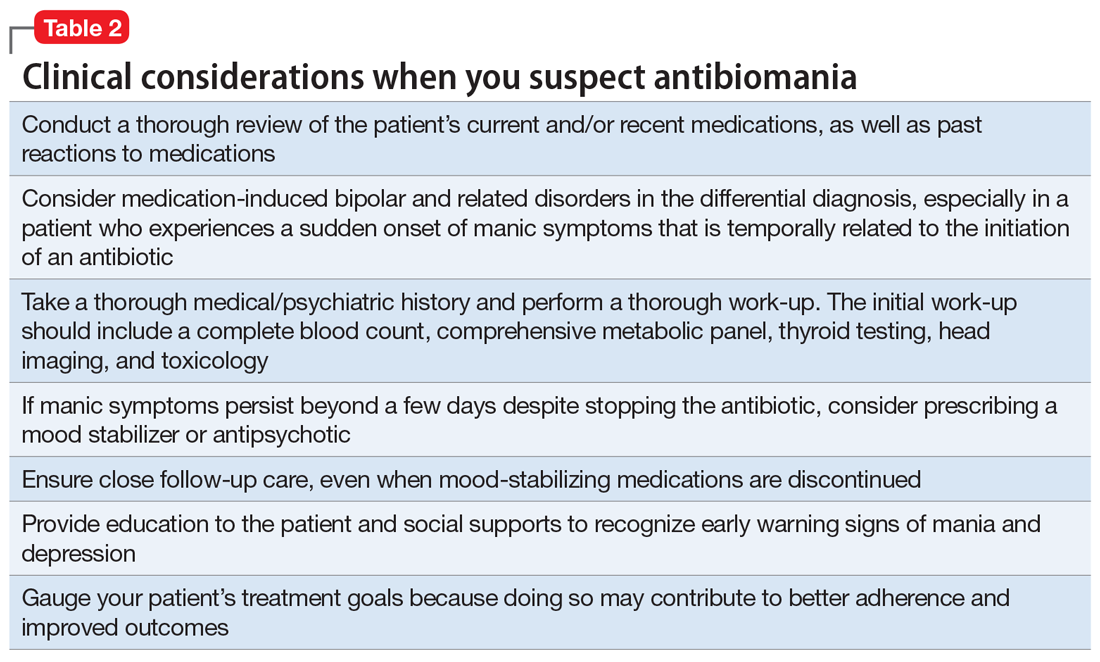

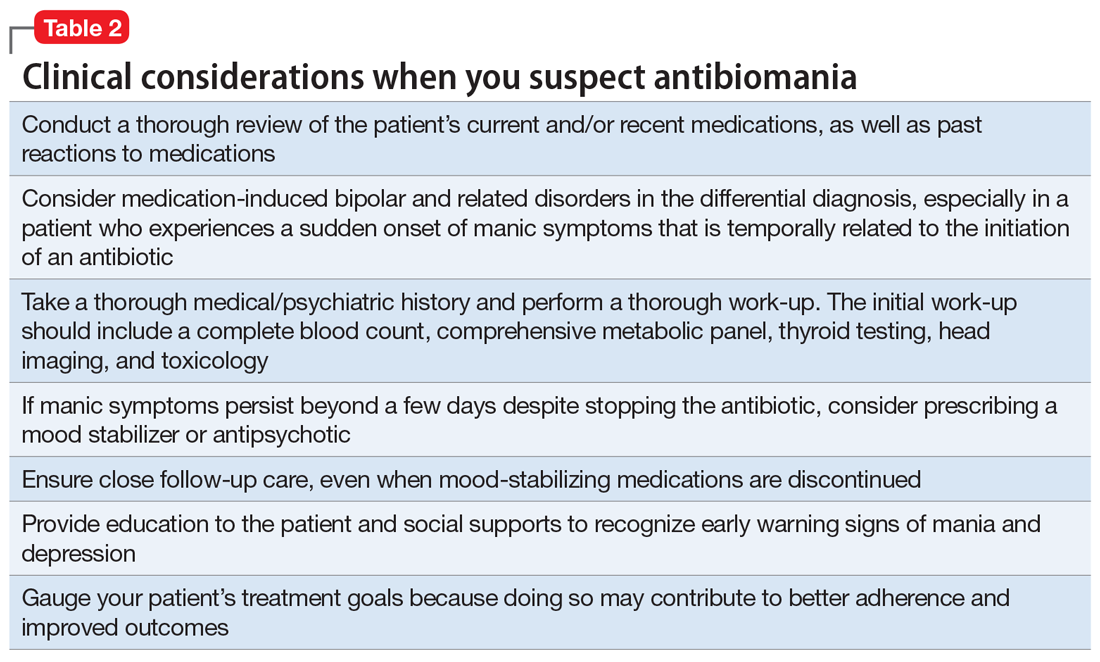

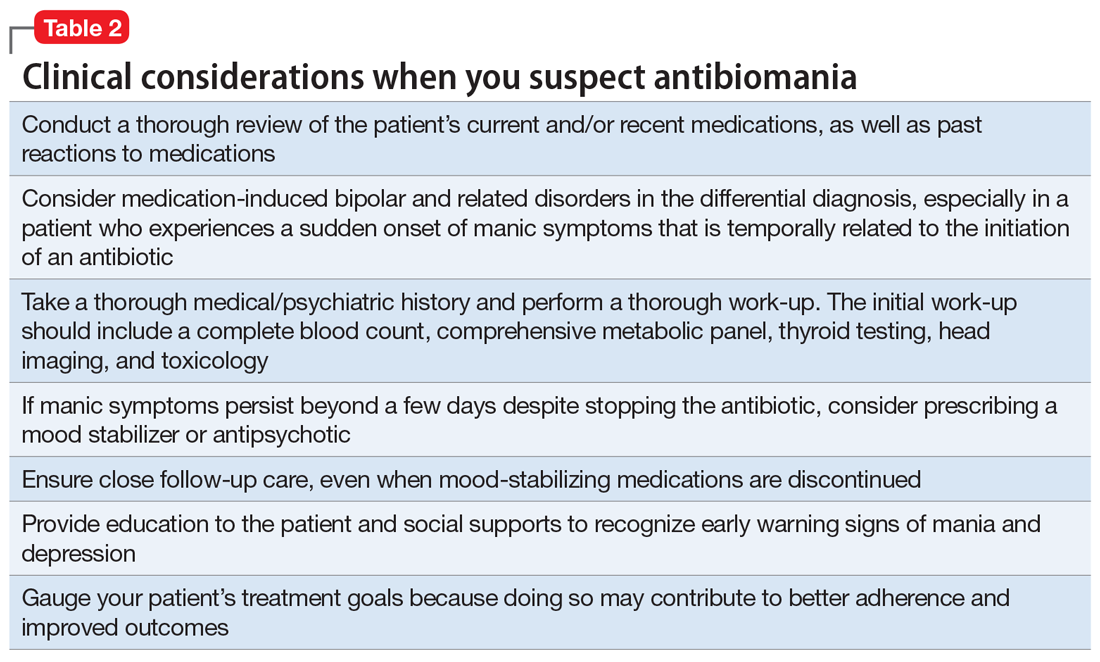

The most likely causes of Mr. R’s manic episode were clomiphene or amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the time course seems to indicate the antibiotic was the most likely culprit. Table 2 lists things to consider if you suspect your patient may be experiencing antibiomania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

During his first visit to the outpatient clinic 4 weeks after being discharged, Mr. R reports that he has successfully returned to work, and his paranoia has completely resolved. He continues to take olanzapine, 10 mg nightly, and has restarted clomiphene, 100 mg/d.

During this outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. R attributes his manic episode to an adverse reaction to amoxicillin/clavulanate, and requests to be tapered off olanzapine. After he and his psychiatrist discuss the risk of relapse in untreated bipolar disorder, olanzapine is reduced to 7.5 mg at bedtime with a plan to taper to discontinuation.

At his second follow-up visit 1 month later, Mr. R has also stopped clomiphene and is taking a herbal supplement instead, which he reports is helpful for his fatigue.

[polldaddy:10485727]

OUTCOME Lasting euthymic mood

Mr. R agrees to our recommendation of continuing to monitor him every 3 months for at least 1 year. We provide him and his wife with education about early warning signs of mood instability. Eight months after his manic episode, Mr. R no longer receives any psychotropic medications and shows no signs of mood instability. His mood remains euthymic and he is able to function well at work and in his personal life.

Bottom Line

‘Antibiomania’ describes manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage. This adverse effect is rare but should be considered in patients who present with unexplained first-episode mania, particularly those with an initial onset of mania after early adulthood.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(7):29-34.

- Adiba A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29

Drug Brand Names

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

Ampicillin • Omnipen-N, Polycillin-N

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Clomiphene • Clomid

Cycloserine • Seromycin

Dapsone • Dapsone

Erythromycin • Erythrocin, Pediamycin

Ethambutol • Myambutol

Ethionamide • Trecator-SC

Gentamicin • Garamycin

Isoniazid • Hyzyd, Nydrazid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Minocycline • Dynacin, Solodyn

Norfloxacin • Noroxin

Ofloxacin • Floxin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Penicillin G procaine • Duracillin A-S, Pfizerpen

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim • Bactrim, Septra

1. Kennedy M, Everitt B, Boydell J, et al. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results for a 35-year study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):855-863.

2. Dols A, Kupka RW, van Lammeren A, et al. The prevalence of late-life mania: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:113-118.

3. Siedontopf F, Horstkamp B, Stief G, et al. Clomiphene citrate as a possible cause of a psychotic reaction during infertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):706-707.

4. Oyffe T, Lerner A, Isaacs G, et al. Clomiphene-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1169-1170.

5. Lambrichts S, Van Oudenhove L, Sienaert P. Antibiotics and mania: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:149-156.

6. Beal DM, Hudson B, Zaiac M. Amoxicillin-induced psychosis? Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):255-256.

7. Klain V, Timmerman L. Antibiomania, acute manic psychosis following the use of antibiotics. European Psychiatry. 2013;28(suppl 1):1.

8. Abouesh A, Stone C, Hobbs WR. Antimicrobial-induced mania (antibiomania): a review of spontaneous reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):71-81.

9. Lally L, Mannion L. The potential for antimicrobials to adversely affect mental state. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. pii: bcr2013009659. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009659.

10. Neufeld NH, Mohamed NS, Grujich N, et al. Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with antibiotic treatment of Helicobactor Pylori infections: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):25-35.

11. Sutter R, Rüegg S, Tschudin-Sutter S. Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1332-1341.

12. Bakhla A, Gore P, Srivastava S. Cycloserine induced mania. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):69-70.

13. Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Trabucchi M, et al. Isoniazid-induced inhibition of GABAergic transmission enhances neurosteroid content in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(9-10):1299-1305.

14. Murphy D, Donnelly C, Moskowitz J. Inhibition by lithium of prostaglandin E1 and norepinephrine effects on cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):810-814.

15. Clay H, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(3):311-324.

16. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

CASE Bipolar-like symptoms

Mr. R, age 48, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) for the third time in 4 days after a change in his behavior over the last 2.5 weeks. He exhibits heightened extroversion, pressured speech, and uncharacteristic irritability. Mr. R’s wife reports that her husband normally is reserved.

Mr. R’s wife first became concerned when she noticed he was not sleeping and spending his nights changing the locks on their home. Mr. R, who is a business executive, occupied his time by taking notes on ways to protect his identity from the senior partners at his company.

Three weeks before his first ED visit, Mr. R had been treated for a neck abscess with incision and drainage. He was sent home with a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875/125 mg by mouth twice daily. There were no reports of steroid use during or after the procedure. Four days after starting the antibiotic, he stopped taking it because he and his wife felt it was contributing to his mood changes and bizarre behavior.

During his first visit to the ED, Mr. R received a 1-time dose of olanzapine, 5 mg by mouth, which helped temporarily reduce his anxiety; however, he returned the following day with the same anxiety symptoms and was discharged with a 30-day prescription for olanzapine, 5 mg/d, to manage symptoms until he could establish care with an outpatient psychiatrist. Two days later, he returned to the ED yet again convinced people were spying on him and that his coworkers were plotting to have him fired. He was not taking his phone to work due to fears that it would be hacked.

Mr. R’s only home medication is clomiphene citrate, 100 mg/d by mouth, which he’s received for the past 7 months to treat low testosterone. He has no personal or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior signs of mania or hypomania.

At the current ED visit, Mr. R’s testosterone level is checked and is within normal limits. His urine drug screen, head CT, and standard laboratory test results are unremarkable, except for mild transaminitis that does not warrant acute management.

The clinicians in the ED establish a diagnosis of mania, unspecified, and psychotic disorder, unspecified. They recommend that Mr. R be admitted for mood stabilization.

[polldaddy:10485725]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Our initial impression was that Mr. R was experiencing a manic episode from undiagnosed bipolar I disorder. The diagnosis was equivocal considering his age, lack of family history, and absence of prior psychiatric symptoms. In most cases, the mean age of onset for mania is late adolescence to early adulthood. It would be less common for a patient to experience a first manic episode at age 48, although mania may emerge at any age. Results from a large British study showed that the incidence of a first manic episode drops from 13.81% in men age 16 to 25 to 2.62% in men age 46 to 55.1 However, some estimates suggest that the prevalence of late-onset mania is much higher than previously expected; medical comorbidities, such as dementia and delirium, may play a significant role in posing as manic-type symptoms in these patients.2

In Mr. R’s case, he remained fully alert and oriented without waxing and waning attentional deficits, which made delirium less likely. His affective symptoms included a reduced need for sleep, anxiety, irritability, rapid speech, and grandiosity lasting at least 2 weeks. He also exhibited psychotic symptoms in the form of paranoia. Altogether, he fit diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder well.

At the time of his manic episode, Mr. R was taking clomiphene. Clomiphene-induced mania and psychosis has been reported scarcely in the literature.3 In these cases, behavioral changes occurred within the first month of clomiphene initiation, which is dissimilar from Mr. R’s timeline.4 However, there appeared to be a temporal relationship between Mr. R’s use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and his manic episode.

This led us to consider whether medication-induced bipolar disorder would be a more appropriate diagnosis. There are documented associations between mania and antibiotics5; however, to our knowledge, mania secondary specifically to amoxicillin/clavulanate has not been reported extensively in the American literature. We found 1 case of suspected amoxicillin-induced psychosis,6 as well as a case report from the Netherlands of possible amoxicillin/clavulanate-induced mania.7

EVALUATION Ongoing paranoia

During his psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. R remains cooperative and polite, but exhibits ongoing paranoia, pressured speech, and poor reality testing. He remains convinced that “people are out to get me,” and routinely scans the room for safety during daily evaluations. He reports that he feels safe in the hospital, but does not feel safe to leave. Mr. R does not recall if in the past he had taken any products containing amoxicillin, but he is able to appreciate changes in his mood after being prescribed the antibiotic. He reports that starting the antibiotic made him feel confident in social interactions.

Continue to: During Mr. R's psychiatric hospitalization...

During Mr. R’s psychiatric hospitalization, olanzapine is titrated to 10 mg at bedtime. Clomiphene citrate is discontinued to limit any potential precipitants of mania, and amoxicillin/clavulanate is not restarted.

Mr. R gradually shows improvement in sleep quality and duration and becomes less irritable. His speech returns to a regular rate and rhythm. He eventually begins to question whether his fears were reality-based. After 4 days, Mr. R is ready to be discharged home and return to work.

[polldaddy:10485726]

The authors’ observations

The term “antibiomania” is used to describe manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage.8 Clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin are the agents most frequently implicated in antibiomania.9 While numerous reports exist in the literature, antibiomania is still considered a rare or unusual adverse event.

The link between infections and neuropsychiatric symptoms is well documented, which makes it challenging to tease apart the role of the acute infection from the use of antibiotics in precipitating psychiatric symptoms. However, in most reported cases of antibiomania, the onset of manic symptoms typically occurs within the first week of antibiotic initiation and resolves 1 to 3 days after medication discontinuation. The temporal relationship between antibiotic initiation and onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been best highlighted in cases where clarithromycin is used to treat a chronic Helicobacter pylori infection.10

While reports of antibiomania date back more than 6 decades, the exact mechanism by which antibiotics cause psychiatric symptoms is mostly unknown, although there are several hypotheses.5 Many hypotheses suggest some antibiotics play a role in reducing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Quinolones, for example, have been found to cross the blood–brain barrier and can inhibit GABA from binding to the receptor sites. This can result in hyper-excitability in the CNS. Several quinolones have been implicated in antibiomania (Table 15). Penicillins are also thought to interfere with GABA neurotransmission in a similar fashion; however, amoxicillin-clavulanate has poor CNS penetration in the absence of blood–brain barrier disruption,11 which makes this theory a less plausible explanation for Mr. R’s case.

Continue to: Another possible mechanism...

Another possible mechanism of antibiotic-induced CNS excitability is through the glutamatergic system. Cycloserine, an antitubercular agent, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) partial agonist and has reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects.12 It has been proposed that quinolones may also have NMDA agonist activity.

The prostaglandin hypothesis suggests that a decrease in GABA may increase concentrations of steroid hormones in the rat CNS.13 Steroids have been implicated in the breakdown of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).13 A disruption in steroid regulation may prevent PGE1 breakdown. Lithium’s antimanic properties are thought to be caused at least in part by limiting prostaglandin production.14 Thus, a shift in PGE1 may lead to mood dysregulation.

Bipolar disorder has been linked with mitochondrial function abnormalities.15 Antibiotics that target ribosomal RNA may disrupt normal mitochondrial function and increase risk for mania precipitation.15 However, amoxicillin exerts its antibiotic effects through binding to penicillin-binding proteins, which leads to inhibition of the cell wall biosynthesis.

Lastly, research into the microbiome has elucidated the gut-brain axis. In animal studies, the microbiome has been found to play a role in immunity, cognitive function, and behavior. Dysbiosis in the microbiome is currently being investigated for its role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.16 Both the microbiome and changes in mitochondrial function are thought to develop over time, so while these are plausible explanations, an onset within 4 days of antibiotic initiation is likely too short of an exposure time to produce these changes.

The most likely causes of Mr. R’s manic episode were clomiphene or amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the time course seems to indicate the antibiotic was the most likely culprit. Table 2 lists things to consider if you suspect your patient may be experiencing antibiomania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

During his first visit to the outpatient clinic 4 weeks after being discharged, Mr. R reports that he has successfully returned to work, and his paranoia has completely resolved. He continues to take olanzapine, 10 mg nightly, and has restarted clomiphene, 100 mg/d.

During this outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. R attributes his manic episode to an adverse reaction to amoxicillin/clavulanate, and requests to be tapered off olanzapine. After he and his psychiatrist discuss the risk of relapse in untreated bipolar disorder, olanzapine is reduced to 7.5 mg at bedtime with a plan to taper to discontinuation.

At his second follow-up visit 1 month later, Mr. R has also stopped clomiphene and is taking a herbal supplement instead, which he reports is helpful for his fatigue.

[polldaddy:10485727]

OUTCOME Lasting euthymic mood

Mr. R agrees to our recommendation of continuing to monitor him every 3 months for at least 1 year. We provide him and his wife with education about early warning signs of mood instability. Eight months after his manic episode, Mr. R no longer receives any psychotropic medications and shows no signs of mood instability. His mood remains euthymic and he is able to function well at work and in his personal life.

Bottom Line

‘Antibiomania’ describes manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage. This adverse effect is rare but should be considered in patients who present with unexplained first-episode mania, particularly those with an initial onset of mania after early adulthood.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(7):29-34.

- Adiba A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29

Drug Brand Names

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

Ampicillin • Omnipen-N, Polycillin-N

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Clomiphene • Clomid

Cycloserine • Seromycin

Dapsone • Dapsone

Erythromycin • Erythrocin, Pediamycin

Ethambutol • Myambutol

Ethionamide • Trecator-SC

Gentamicin • Garamycin

Isoniazid • Hyzyd, Nydrazid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Minocycline • Dynacin, Solodyn

Norfloxacin • Noroxin

Ofloxacin • Floxin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Penicillin G procaine • Duracillin A-S, Pfizerpen

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim • Bactrim, Septra

CASE Bipolar-like symptoms

Mr. R, age 48, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) for the third time in 4 days after a change in his behavior over the last 2.5 weeks. He exhibits heightened extroversion, pressured speech, and uncharacteristic irritability. Mr. R’s wife reports that her husband normally is reserved.

Mr. R’s wife first became concerned when she noticed he was not sleeping and spending his nights changing the locks on their home. Mr. R, who is a business executive, occupied his time by taking notes on ways to protect his identity from the senior partners at his company.

Three weeks before his first ED visit, Mr. R had been treated for a neck abscess with incision and drainage. He was sent home with a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875/125 mg by mouth twice daily. There were no reports of steroid use during or after the procedure. Four days after starting the antibiotic, he stopped taking it because he and his wife felt it was contributing to his mood changes and bizarre behavior.

During his first visit to the ED, Mr. R received a 1-time dose of olanzapine, 5 mg by mouth, which helped temporarily reduce his anxiety; however, he returned the following day with the same anxiety symptoms and was discharged with a 30-day prescription for olanzapine, 5 mg/d, to manage symptoms until he could establish care with an outpatient psychiatrist. Two days later, he returned to the ED yet again convinced people were spying on him and that his coworkers were plotting to have him fired. He was not taking his phone to work due to fears that it would be hacked.

Mr. R’s only home medication is clomiphene citrate, 100 mg/d by mouth, which he’s received for the past 7 months to treat low testosterone. He has no personal or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior signs of mania or hypomania.

At the current ED visit, Mr. R’s testosterone level is checked and is within normal limits. His urine drug screen, head CT, and standard laboratory test results are unremarkable, except for mild transaminitis that does not warrant acute management.

The clinicians in the ED establish a diagnosis of mania, unspecified, and psychotic disorder, unspecified. They recommend that Mr. R be admitted for mood stabilization.

[polldaddy:10485725]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Our initial impression was that Mr. R was experiencing a manic episode from undiagnosed bipolar I disorder. The diagnosis was equivocal considering his age, lack of family history, and absence of prior psychiatric symptoms. In most cases, the mean age of onset for mania is late adolescence to early adulthood. It would be less common for a patient to experience a first manic episode at age 48, although mania may emerge at any age. Results from a large British study showed that the incidence of a first manic episode drops from 13.81% in men age 16 to 25 to 2.62% in men age 46 to 55.1 However, some estimates suggest that the prevalence of late-onset mania is much higher than previously expected; medical comorbidities, such as dementia and delirium, may play a significant role in posing as manic-type symptoms in these patients.2

In Mr. R’s case, he remained fully alert and oriented without waxing and waning attentional deficits, which made delirium less likely. His affective symptoms included a reduced need for sleep, anxiety, irritability, rapid speech, and grandiosity lasting at least 2 weeks. He also exhibited psychotic symptoms in the form of paranoia. Altogether, he fit diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder well.

At the time of his manic episode, Mr. R was taking clomiphene. Clomiphene-induced mania and psychosis has been reported scarcely in the literature.3 In these cases, behavioral changes occurred within the first month of clomiphene initiation, which is dissimilar from Mr. R’s timeline.4 However, there appeared to be a temporal relationship between Mr. R’s use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and his manic episode.

This led us to consider whether medication-induced bipolar disorder would be a more appropriate diagnosis. There are documented associations between mania and antibiotics5; however, to our knowledge, mania secondary specifically to amoxicillin/clavulanate has not been reported extensively in the American literature. We found 1 case of suspected amoxicillin-induced psychosis,6 as well as a case report from the Netherlands of possible amoxicillin/clavulanate-induced mania.7

EVALUATION Ongoing paranoia

During his psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. R remains cooperative and polite, but exhibits ongoing paranoia, pressured speech, and poor reality testing. He remains convinced that “people are out to get me,” and routinely scans the room for safety during daily evaluations. He reports that he feels safe in the hospital, but does not feel safe to leave. Mr. R does not recall if in the past he had taken any products containing amoxicillin, but he is able to appreciate changes in his mood after being prescribed the antibiotic. He reports that starting the antibiotic made him feel confident in social interactions.

Continue to: During Mr. R's psychiatric hospitalization...

During Mr. R’s psychiatric hospitalization, olanzapine is titrated to 10 mg at bedtime. Clomiphene citrate is discontinued to limit any potential precipitants of mania, and amoxicillin/clavulanate is not restarted.

Mr. R gradually shows improvement in sleep quality and duration and becomes less irritable. His speech returns to a regular rate and rhythm. He eventually begins to question whether his fears were reality-based. After 4 days, Mr. R is ready to be discharged home and return to work.

[polldaddy:10485726]

The authors’ observations

The term “antibiomania” is used to describe manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage.8 Clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin are the agents most frequently implicated in antibiomania.9 While numerous reports exist in the literature, antibiomania is still considered a rare or unusual adverse event.

The link between infections and neuropsychiatric symptoms is well documented, which makes it challenging to tease apart the role of the acute infection from the use of antibiotics in precipitating psychiatric symptoms. However, in most reported cases of antibiomania, the onset of manic symptoms typically occurs within the first week of antibiotic initiation and resolves 1 to 3 days after medication discontinuation. The temporal relationship between antibiotic initiation and onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been best highlighted in cases where clarithromycin is used to treat a chronic Helicobacter pylori infection.10

While reports of antibiomania date back more than 6 decades, the exact mechanism by which antibiotics cause psychiatric symptoms is mostly unknown, although there are several hypotheses.5 Many hypotheses suggest some antibiotics play a role in reducing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Quinolones, for example, have been found to cross the blood–brain barrier and can inhibit GABA from binding to the receptor sites. This can result in hyper-excitability in the CNS. Several quinolones have been implicated in antibiomania (Table 15). Penicillins are also thought to interfere with GABA neurotransmission in a similar fashion; however, amoxicillin-clavulanate has poor CNS penetration in the absence of blood–brain barrier disruption,11 which makes this theory a less plausible explanation for Mr. R’s case.

Continue to: Another possible mechanism...

Another possible mechanism of antibiotic-induced CNS excitability is through the glutamatergic system. Cycloserine, an antitubercular agent, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) partial agonist and has reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects.12 It has been proposed that quinolones may also have NMDA agonist activity.

The prostaglandin hypothesis suggests that a decrease in GABA may increase concentrations of steroid hormones in the rat CNS.13 Steroids have been implicated in the breakdown of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).13 A disruption in steroid regulation may prevent PGE1 breakdown. Lithium’s antimanic properties are thought to be caused at least in part by limiting prostaglandin production.14 Thus, a shift in PGE1 may lead to mood dysregulation.

Bipolar disorder has been linked with mitochondrial function abnormalities.15 Antibiotics that target ribosomal RNA may disrupt normal mitochondrial function and increase risk for mania precipitation.15 However, amoxicillin exerts its antibiotic effects through binding to penicillin-binding proteins, which leads to inhibition of the cell wall biosynthesis.

Lastly, research into the microbiome has elucidated the gut-brain axis. In animal studies, the microbiome has been found to play a role in immunity, cognitive function, and behavior. Dysbiosis in the microbiome is currently being investigated for its role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.16 Both the microbiome and changes in mitochondrial function are thought to develop over time, so while these are plausible explanations, an onset within 4 days of antibiotic initiation is likely too short of an exposure time to produce these changes.

The most likely causes of Mr. R’s manic episode were clomiphene or amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the time course seems to indicate the antibiotic was the most likely culprit. Table 2 lists things to consider if you suspect your patient may be experiencing antibiomania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

During his first visit to the outpatient clinic 4 weeks after being discharged, Mr. R reports that he has successfully returned to work, and his paranoia has completely resolved. He continues to take olanzapine, 10 mg nightly, and has restarted clomiphene, 100 mg/d.

During this outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. R attributes his manic episode to an adverse reaction to amoxicillin/clavulanate, and requests to be tapered off olanzapine. After he and his psychiatrist discuss the risk of relapse in untreated bipolar disorder, olanzapine is reduced to 7.5 mg at bedtime with a plan to taper to discontinuation.

At his second follow-up visit 1 month later, Mr. R has also stopped clomiphene and is taking a herbal supplement instead, which he reports is helpful for his fatigue.

[polldaddy:10485727]

OUTCOME Lasting euthymic mood

Mr. R agrees to our recommendation of continuing to monitor him every 3 months for at least 1 year. We provide him and his wife with education about early warning signs of mood instability. Eight months after his manic episode, Mr. R no longer receives any psychotropic medications and shows no signs of mood instability. His mood remains euthymic and he is able to function well at work and in his personal life.

Bottom Line

‘Antibiomania’ describes manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage. This adverse effect is rare but should be considered in patients who present with unexplained first-episode mania, particularly those with an initial onset of mania after early adulthood.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(7):29-34.

- Adiba A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29

Drug Brand Names

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

Ampicillin • Omnipen-N, Polycillin-N

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Clomiphene • Clomid

Cycloserine • Seromycin

Dapsone • Dapsone

Erythromycin • Erythrocin, Pediamycin

Ethambutol • Myambutol

Ethionamide • Trecator-SC

Gentamicin • Garamycin

Isoniazid • Hyzyd, Nydrazid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Minocycline • Dynacin, Solodyn

Norfloxacin • Noroxin

Ofloxacin • Floxin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Penicillin G procaine • Duracillin A-S, Pfizerpen

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim • Bactrim, Septra

1. Kennedy M, Everitt B, Boydell J, et al. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results for a 35-year study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):855-863.

2. Dols A, Kupka RW, van Lammeren A, et al. The prevalence of late-life mania: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:113-118.

3. Siedontopf F, Horstkamp B, Stief G, et al. Clomiphene citrate as a possible cause of a psychotic reaction during infertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):706-707.

4. Oyffe T, Lerner A, Isaacs G, et al. Clomiphene-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1169-1170.

5. Lambrichts S, Van Oudenhove L, Sienaert P. Antibiotics and mania: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:149-156.

6. Beal DM, Hudson B, Zaiac M. Amoxicillin-induced psychosis? Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):255-256.

7. Klain V, Timmerman L. Antibiomania, acute manic psychosis following the use of antibiotics. European Psychiatry. 2013;28(suppl 1):1.

8. Abouesh A, Stone C, Hobbs WR. Antimicrobial-induced mania (antibiomania): a review of spontaneous reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):71-81.

9. Lally L, Mannion L. The potential for antimicrobials to adversely affect mental state. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. pii: bcr2013009659. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009659.

10. Neufeld NH, Mohamed NS, Grujich N, et al. Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with antibiotic treatment of Helicobactor Pylori infections: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):25-35.

11. Sutter R, Rüegg S, Tschudin-Sutter S. Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1332-1341.

12. Bakhla A, Gore P, Srivastava S. Cycloserine induced mania. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):69-70.

13. Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Trabucchi M, et al. Isoniazid-induced inhibition of GABAergic transmission enhances neurosteroid content in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(9-10):1299-1305.

14. Murphy D, Donnelly C, Moskowitz J. Inhibition by lithium of prostaglandin E1 and norepinephrine effects on cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):810-814.

15. Clay H, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(3):311-324.

16. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

1. Kennedy M, Everitt B, Boydell J, et al. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results for a 35-year study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):855-863.

2. Dols A, Kupka RW, van Lammeren A, et al. The prevalence of late-life mania: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:113-118.

3. Siedontopf F, Horstkamp B, Stief G, et al. Clomiphene citrate as a possible cause of a psychotic reaction during infertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):706-707.

4. Oyffe T, Lerner A, Isaacs G, et al. Clomiphene-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1169-1170.

5. Lambrichts S, Van Oudenhove L, Sienaert P. Antibiotics and mania: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:149-156.

6. Beal DM, Hudson B, Zaiac M. Amoxicillin-induced psychosis? Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):255-256.

7. Klain V, Timmerman L. Antibiomania, acute manic psychosis following the use of antibiotics. European Psychiatry. 2013;28(suppl 1):1.

8. Abouesh A, Stone C, Hobbs WR. Antimicrobial-induced mania (antibiomania): a review of spontaneous reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):71-81.

9. Lally L, Mannion L. The potential for antimicrobials to adversely affect mental state. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. pii: bcr2013009659. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009659.

10. Neufeld NH, Mohamed NS, Grujich N, et al. Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with antibiotic treatment of Helicobactor Pylori infections: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):25-35.

11. Sutter R, Rüegg S, Tschudin-Sutter S. Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1332-1341.

12. Bakhla A, Gore P, Srivastava S. Cycloserine induced mania. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):69-70.

13. Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Trabucchi M, et al. Isoniazid-induced inhibition of GABAergic transmission enhances neurosteroid content in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(9-10):1299-1305.

14. Murphy D, Donnelly C, Moskowitz J. Inhibition by lithium of prostaglandin E1 and norepinephrine effects on cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):810-814.

15. Clay H, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(3):311-324.

16. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.