User login

with implications that may extend to cardiovascular disease in general.

In the study involving more than 900 patients with PH, investigators at seven U.S. centers determined the prevalence of iron deficiency by two separate definitions and assessed its associations with functional measures and quality of life (QoL) scores.

An iron deficiency definition used conventionally in heart failure (HF) – ferritin less than 100 g/mL or 100-299 ng/mL with transferrin saturation (TSAT) less than 20% – failed to discriminate patients with reduced peak oxygen consumption (peakVO2), 6-minute walk test (6MWT) results, and QoL scores on the 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36).

But an alternative definition for iron deficiency, simply a TSAT less than 21%, did predict such patients with reduced peakVO2, 6MWT, and QoL. It was also associated with an increased mortality risk. The study was published in the European Heart Journal.

“A low TSAT, less than 21%, is key in the pathophysiology of iron deficiency in pulmonary hypertension” and is associated with those important clinical and functional characteristics, lead author Pieter Martens MD, PhD, said in an interview. The study “underscores the importance of these criteria in future intervention studies in the field of pulmonary hypertension testing iron therapies.”

A broader implication is that “we should revise how we define iron deficiency in heart failure and cardiovascular disease in general and how we select patients for iron therapies,” said Dr. Martens, of the Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic.

Iron’s role in pulmonary vascular disease

“Iron deficiency is associated with an energetic deficit, especially in high energy–demanding tissue, leading to early skeletal muscle acidification and diminished left and right ventricular (RV) contractile reserve during exercise,” the published report states. It can lead to “maladaptive RV remodeling,” which is a “hallmark feature” predictive of morbidity and mortality in patients with pulmonary vascular disease (PVD).

Some studies have suggested that iron deficiency is a common comorbidity in patients with PVD, their estimates of its prevalence ranging widely due in part to the “absence of a uniform definition,” write the authors.

Dr. Martens said the current study was conducted partly in response to the increasingly common observation that the HF-associated definition of iron deficiency “has limitations.” Yet, “without validation in the field of pulmonary hypertension, the 2022 pulmonary hypertension guidelines endorse this definition.”

As iron deficiency is a causal risk factor for HF progression, Dr. Martens added, the HF field has “taught us the importance of using validated definitions for iron deficiency when selecting patients for iron treatment in randomized controlled trials.”

Moreover, some evidence suggests that iron deficiency by some definitions may be associated with diminished exercise capacity and QoL in patients with PVD, which are associations that have not been confirmed in large studies, the report notes.

Therefore, it continues, the study sought to “determine and validate” the optimal definition of iron deficiency in patients with PVD; document its prevalence; and explore associations between iron deficiency and exercise capacity, QoL, and cardiac and pulmonary vascular remodeling.

Evaluating definitions of iron deficiency

The prospective study, called PVDOMICS, entered 1,195 subjects with available iron levels. After exclusion of 38 patients with sarcoidosis, myeloproliferative disease, or hemoglobinopathy, there remained 693 patients with “overt” PH, 225 with a milder form of PH who served as PVD comparators, and 90 age-, sex-, race/ethnicity- matched “healthy” adults who served as controls.

According to the conventional HF definition of iron deficiency – that is, ferritin 100-299 ng/mL and TSAT less than 20% – the prevalences were 74% in patients with overt PH and 72% of those “across the PVD spectrum.”

But by that definition, iron deficient and non-iron deficient patients didn’t differ significantly in peakVO2, 6MWT distance, or SF-36 physical component scores.

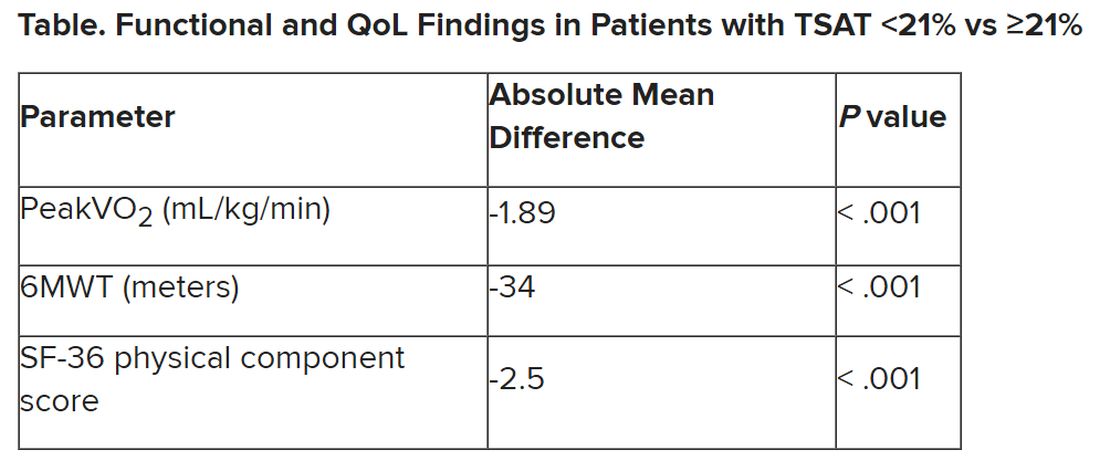

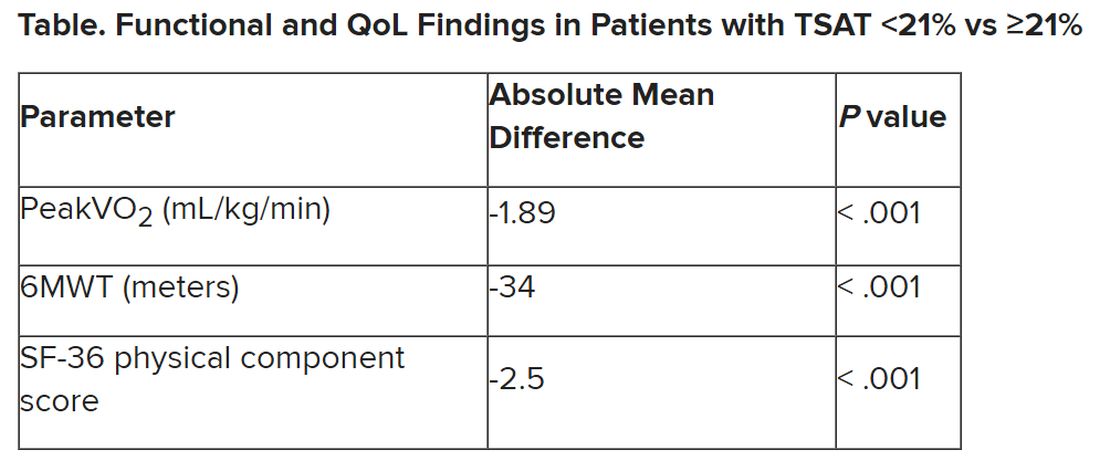

In contrast, patients meeting the alternative definition of iron deficiency of TSAT less than 21% showed significantly reduced functional and QoL measures, compared with those with TSAT greater than or equal to 21%.

The group with TSAT less than 21% also showed significantly more RV remodeling at cardiac MRI, compared with those who had TSAT greater than or equal to 21%, but their invasively measured pulmonary vascular resistance was comparable.

Of note, those with TSAT less than 21% also showed significantly increased all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-2.34; P = .009) after adjustment for age, sex, hemoglobin, and natriuretic peptide levels.

“Proper validation of the definition of iron deficiency is important for prognostication,” the published report states, “but also for providing a working definition that can be used to identify suitable patients for inclusion in randomized controlled trials” of drugs for iron deficiency.

Additionally, the finding that TSAT less than 21% points to patients with diminished functional and exercise capacity is “consistent with more recent studies in the field of heart failure” that suggest “functional abnormalities and adverse cardiac remodeling are worse in patients with a low TSAT.” Indeed, the report states, such treatment effects have been “the most convincing” in HF trials.

Broader implications

An accompanying editorial agrees that the study’s implications apply well beyond PH. It highlights that iron deficiency is common in PH, while such PH is “not substantially different from the problem in patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease in general,” lead editorialist John G.F. Cleland, MD, PhD, University of Glasgow, said in an interview. “It’s also common as people get older, even in those without these diseases.”

Dr. Cleland said the anemia definition currently used in cardiovascular research and practice is based on a hemoglobin concentration below the 5th percentile of age and sex in primarily young, healthy people, and not on its association with clinical outcomes.

“We recently analyzed data on a large population in the United Kingdom with a broad range of cardiovascular diseases and found that unless anemia is severe, [other] markers of iron deficiency are usually not measured,” he said. A low hemoglobin and TSAT, but not low ferritin levels, are associated with worse prognosis.

Dr. Cleland agreed that the HF-oriented definition is “poor,” with profound implications for the conduct of clinical trials. “If the definition of iron deficiency lacks specificity, then clinical trials will include many patients without iron deficiency who are unlikely to benefit from and might be harmed by IV iron.” Inclusion of such patients may also “dilute” any benefit that might emerge and render the outcome inaccurate.

But if the definition of iron deficiency lacks sensitivity, “then in clinical practice, many patients with iron deficiency may be denied a simple and effective treatment.”

Measuring serum iron could potentially be useful, but it’s usually not done in randomized trials “especially since taking an iron tablet can give a temporary ‘blip’ in serum iron,” Dr. Cleland said. “So TSAT is a reasonable compromise.” He said he “looks forward” to any further data on serum iron as a way of assessing iron deficiency and anemia.

Half full vs. half empty

Dr. Cleland likened the question of whom to treat with iron supplementation as a “glass half full versus half empty” clinical dilemma. “One approach is to give iron to everyone unless there’s evidence that they’re overloaded,” he said, “while the other is to withhold iron from everyone unless there’s evidence that they’re iron depleted.”

Recent evidence from the IRONMAN trial suggested that its patients with HF who received intravenous iron were less likely to be hospitalized for infections, particularly COVID-19, than a usual-care group. The treatment may also help reduce frailty.

“So should we be offering IV iron specifically to people considered iron deficient, or should we be ensuring that everyone over age 70 get iron supplements?” Dr. Cleland mused rhetorically. On a cautionary note, he added, perhaps iron supplementation will be harmful if it’s not necessary.

Dr. Cleland proposed “focusing for the moment on people who are iron deficient but investigating the possibility that we are being overly restrictive and should be giving iron to a much broader population.” That course, however, would require large population-based studies.

“We need more experience,” Dr. Cleland said, “to make sure that the benefits outweigh any risks before we can just give iron to everyone.”

Dr. Martens has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Abbott, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Vifor Pharma. Dr. Cleland declares grant support, support for travel, and personal honoraria from Pharmacosmos and Vifor. Disclosures for other authors are in the published report and editorial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

with implications that may extend to cardiovascular disease in general.

In the study involving more than 900 patients with PH, investigators at seven U.S. centers determined the prevalence of iron deficiency by two separate definitions and assessed its associations with functional measures and quality of life (QoL) scores.

An iron deficiency definition used conventionally in heart failure (HF) – ferritin less than 100 g/mL or 100-299 ng/mL with transferrin saturation (TSAT) less than 20% – failed to discriminate patients with reduced peak oxygen consumption (peakVO2), 6-minute walk test (6MWT) results, and QoL scores on the 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36).

But an alternative definition for iron deficiency, simply a TSAT less than 21%, did predict such patients with reduced peakVO2, 6MWT, and QoL. It was also associated with an increased mortality risk. The study was published in the European Heart Journal.

“A low TSAT, less than 21%, is key in the pathophysiology of iron deficiency in pulmonary hypertension” and is associated with those important clinical and functional characteristics, lead author Pieter Martens MD, PhD, said in an interview. The study “underscores the importance of these criteria in future intervention studies in the field of pulmonary hypertension testing iron therapies.”

A broader implication is that “we should revise how we define iron deficiency in heart failure and cardiovascular disease in general and how we select patients for iron therapies,” said Dr. Martens, of the Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic.

Iron’s role in pulmonary vascular disease

“Iron deficiency is associated with an energetic deficit, especially in high energy–demanding tissue, leading to early skeletal muscle acidification and diminished left and right ventricular (RV) contractile reserve during exercise,” the published report states. It can lead to “maladaptive RV remodeling,” which is a “hallmark feature” predictive of morbidity and mortality in patients with pulmonary vascular disease (PVD).

Some studies have suggested that iron deficiency is a common comorbidity in patients with PVD, their estimates of its prevalence ranging widely due in part to the “absence of a uniform definition,” write the authors.

Dr. Martens said the current study was conducted partly in response to the increasingly common observation that the HF-associated definition of iron deficiency “has limitations.” Yet, “without validation in the field of pulmonary hypertension, the 2022 pulmonary hypertension guidelines endorse this definition.”

As iron deficiency is a causal risk factor for HF progression, Dr. Martens added, the HF field has “taught us the importance of using validated definitions for iron deficiency when selecting patients for iron treatment in randomized controlled trials.”

Moreover, some evidence suggests that iron deficiency by some definitions may be associated with diminished exercise capacity and QoL in patients with PVD, which are associations that have not been confirmed in large studies, the report notes.

Therefore, it continues, the study sought to “determine and validate” the optimal definition of iron deficiency in patients with PVD; document its prevalence; and explore associations between iron deficiency and exercise capacity, QoL, and cardiac and pulmonary vascular remodeling.

Evaluating definitions of iron deficiency

The prospective study, called PVDOMICS, entered 1,195 subjects with available iron levels. After exclusion of 38 patients with sarcoidosis, myeloproliferative disease, or hemoglobinopathy, there remained 693 patients with “overt” PH, 225 with a milder form of PH who served as PVD comparators, and 90 age-, sex-, race/ethnicity- matched “healthy” adults who served as controls.

According to the conventional HF definition of iron deficiency – that is, ferritin 100-299 ng/mL and TSAT less than 20% – the prevalences were 74% in patients with overt PH and 72% of those “across the PVD spectrum.”

But by that definition, iron deficient and non-iron deficient patients didn’t differ significantly in peakVO2, 6MWT distance, or SF-36 physical component scores.

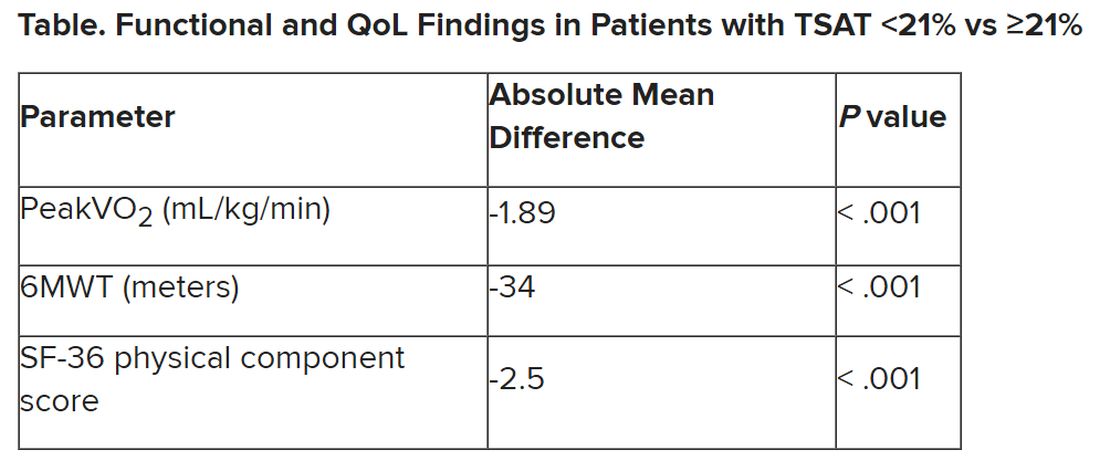

In contrast, patients meeting the alternative definition of iron deficiency of TSAT less than 21% showed significantly reduced functional and QoL measures, compared with those with TSAT greater than or equal to 21%.

The group with TSAT less than 21% also showed significantly more RV remodeling at cardiac MRI, compared with those who had TSAT greater than or equal to 21%, but their invasively measured pulmonary vascular resistance was comparable.

Of note, those with TSAT less than 21% also showed significantly increased all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-2.34; P = .009) after adjustment for age, sex, hemoglobin, and natriuretic peptide levels.

“Proper validation of the definition of iron deficiency is important for prognostication,” the published report states, “but also for providing a working definition that can be used to identify suitable patients for inclusion in randomized controlled trials” of drugs for iron deficiency.

Additionally, the finding that TSAT less than 21% points to patients with diminished functional and exercise capacity is “consistent with more recent studies in the field of heart failure” that suggest “functional abnormalities and adverse cardiac remodeling are worse in patients with a low TSAT.” Indeed, the report states, such treatment effects have been “the most convincing” in HF trials.

Broader implications

An accompanying editorial agrees that the study’s implications apply well beyond PH. It highlights that iron deficiency is common in PH, while such PH is “not substantially different from the problem in patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease in general,” lead editorialist John G.F. Cleland, MD, PhD, University of Glasgow, said in an interview. “It’s also common as people get older, even in those without these diseases.”

Dr. Cleland said the anemia definition currently used in cardiovascular research and practice is based on a hemoglobin concentration below the 5th percentile of age and sex in primarily young, healthy people, and not on its association with clinical outcomes.

“We recently analyzed data on a large population in the United Kingdom with a broad range of cardiovascular diseases and found that unless anemia is severe, [other] markers of iron deficiency are usually not measured,” he said. A low hemoglobin and TSAT, but not low ferritin levels, are associated with worse prognosis.

Dr. Cleland agreed that the HF-oriented definition is “poor,” with profound implications for the conduct of clinical trials. “If the definition of iron deficiency lacks specificity, then clinical trials will include many patients without iron deficiency who are unlikely to benefit from and might be harmed by IV iron.” Inclusion of such patients may also “dilute” any benefit that might emerge and render the outcome inaccurate.

But if the definition of iron deficiency lacks sensitivity, “then in clinical practice, many patients with iron deficiency may be denied a simple and effective treatment.”

Measuring serum iron could potentially be useful, but it’s usually not done in randomized trials “especially since taking an iron tablet can give a temporary ‘blip’ in serum iron,” Dr. Cleland said. “So TSAT is a reasonable compromise.” He said he “looks forward” to any further data on serum iron as a way of assessing iron deficiency and anemia.

Half full vs. half empty

Dr. Cleland likened the question of whom to treat with iron supplementation as a “glass half full versus half empty” clinical dilemma. “One approach is to give iron to everyone unless there’s evidence that they’re overloaded,” he said, “while the other is to withhold iron from everyone unless there’s evidence that they’re iron depleted.”

Recent evidence from the IRONMAN trial suggested that its patients with HF who received intravenous iron were less likely to be hospitalized for infections, particularly COVID-19, than a usual-care group. The treatment may also help reduce frailty.

“So should we be offering IV iron specifically to people considered iron deficient, or should we be ensuring that everyone over age 70 get iron supplements?” Dr. Cleland mused rhetorically. On a cautionary note, he added, perhaps iron supplementation will be harmful if it’s not necessary.

Dr. Cleland proposed “focusing for the moment on people who are iron deficient but investigating the possibility that we are being overly restrictive and should be giving iron to a much broader population.” That course, however, would require large population-based studies.

“We need more experience,” Dr. Cleland said, “to make sure that the benefits outweigh any risks before we can just give iron to everyone.”

Dr. Martens has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Abbott, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Vifor Pharma. Dr. Cleland declares grant support, support for travel, and personal honoraria from Pharmacosmos and Vifor. Disclosures for other authors are in the published report and editorial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

with implications that may extend to cardiovascular disease in general.

In the study involving more than 900 patients with PH, investigators at seven U.S. centers determined the prevalence of iron deficiency by two separate definitions and assessed its associations with functional measures and quality of life (QoL) scores.

An iron deficiency definition used conventionally in heart failure (HF) – ferritin less than 100 g/mL or 100-299 ng/mL with transferrin saturation (TSAT) less than 20% – failed to discriminate patients with reduced peak oxygen consumption (peakVO2), 6-minute walk test (6MWT) results, and QoL scores on the 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36).

But an alternative definition for iron deficiency, simply a TSAT less than 21%, did predict such patients with reduced peakVO2, 6MWT, and QoL. It was also associated with an increased mortality risk. The study was published in the European Heart Journal.

“A low TSAT, less than 21%, is key in the pathophysiology of iron deficiency in pulmonary hypertension” and is associated with those important clinical and functional characteristics, lead author Pieter Martens MD, PhD, said in an interview. The study “underscores the importance of these criteria in future intervention studies in the field of pulmonary hypertension testing iron therapies.”

A broader implication is that “we should revise how we define iron deficiency in heart failure and cardiovascular disease in general and how we select patients for iron therapies,” said Dr. Martens, of the Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic.

Iron’s role in pulmonary vascular disease

“Iron deficiency is associated with an energetic deficit, especially in high energy–demanding tissue, leading to early skeletal muscle acidification and diminished left and right ventricular (RV) contractile reserve during exercise,” the published report states. It can lead to “maladaptive RV remodeling,” which is a “hallmark feature” predictive of morbidity and mortality in patients with pulmonary vascular disease (PVD).

Some studies have suggested that iron deficiency is a common comorbidity in patients with PVD, their estimates of its prevalence ranging widely due in part to the “absence of a uniform definition,” write the authors.

Dr. Martens said the current study was conducted partly in response to the increasingly common observation that the HF-associated definition of iron deficiency “has limitations.” Yet, “without validation in the field of pulmonary hypertension, the 2022 pulmonary hypertension guidelines endorse this definition.”

As iron deficiency is a causal risk factor for HF progression, Dr. Martens added, the HF field has “taught us the importance of using validated definitions for iron deficiency when selecting patients for iron treatment in randomized controlled trials.”

Moreover, some evidence suggests that iron deficiency by some definitions may be associated with diminished exercise capacity and QoL in patients with PVD, which are associations that have not been confirmed in large studies, the report notes.

Therefore, it continues, the study sought to “determine and validate” the optimal definition of iron deficiency in patients with PVD; document its prevalence; and explore associations between iron deficiency and exercise capacity, QoL, and cardiac and pulmonary vascular remodeling.

Evaluating definitions of iron deficiency

The prospective study, called PVDOMICS, entered 1,195 subjects with available iron levels. After exclusion of 38 patients with sarcoidosis, myeloproliferative disease, or hemoglobinopathy, there remained 693 patients with “overt” PH, 225 with a milder form of PH who served as PVD comparators, and 90 age-, sex-, race/ethnicity- matched “healthy” adults who served as controls.

According to the conventional HF definition of iron deficiency – that is, ferritin 100-299 ng/mL and TSAT less than 20% – the prevalences were 74% in patients with overt PH and 72% of those “across the PVD spectrum.”

But by that definition, iron deficient and non-iron deficient patients didn’t differ significantly in peakVO2, 6MWT distance, or SF-36 physical component scores.

In contrast, patients meeting the alternative definition of iron deficiency of TSAT less than 21% showed significantly reduced functional and QoL measures, compared with those with TSAT greater than or equal to 21%.

The group with TSAT less than 21% also showed significantly more RV remodeling at cardiac MRI, compared with those who had TSAT greater than or equal to 21%, but their invasively measured pulmonary vascular resistance was comparable.

Of note, those with TSAT less than 21% also showed significantly increased all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-2.34; P = .009) after adjustment for age, sex, hemoglobin, and natriuretic peptide levels.

“Proper validation of the definition of iron deficiency is important for prognostication,” the published report states, “but also for providing a working definition that can be used to identify suitable patients for inclusion in randomized controlled trials” of drugs for iron deficiency.

Additionally, the finding that TSAT less than 21% points to patients with diminished functional and exercise capacity is “consistent with more recent studies in the field of heart failure” that suggest “functional abnormalities and adverse cardiac remodeling are worse in patients with a low TSAT.” Indeed, the report states, such treatment effects have been “the most convincing” in HF trials.

Broader implications

An accompanying editorial agrees that the study’s implications apply well beyond PH. It highlights that iron deficiency is common in PH, while such PH is “not substantially different from the problem in patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease in general,” lead editorialist John G.F. Cleland, MD, PhD, University of Glasgow, said in an interview. “It’s also common as people get older, even in those without these diseases.”

Dr. Cleland said the anemia definition currently used in cardiovascular research and practice is based on a hemoglobin concentration below the 5th percentile of age and sex in primarily young, healthy people, and not on its association with clinical outcomes.

“We recently analyzed data on a large population in the United Kingdom with a broad range of cardiovascular diseases and found that unless anemia is severe, [other] markers of iron deficiency are usually not measured,” he said. A low hemoglobin and TSAT, but not low ferritin levels, are associated with worse prognosis.

Dr. Cleland agreed that the HF-oriented definition is “poor,” with profound implications for the conduct of clinical trials. “If the definition of iron deficiency lacks specificity, then clinical trials will include many patients without iron deficiency who are unlikely to benefit from and might be harmed by IV iron.” Inclusion of such patients may also “dilute” any benefit that might emerge and render the outcome inaccurate.

But if the definition of iron deficiency lacks sensitivity, “then in clinical practice, many patients with iron deficiency may be denied a simple and effective treatment.”

Measuring serum iron could potentially be useful, but it’s usually not done in randomized trials “especially since taking an iron tablet can give a temporary ‘blip’ in serum iron,” Dr. Cleland said. “So TSAT is a reasonable compromise.” He said he “looks forward” to any further data on serum iron as a way of assessing iron deficiency and anemia.

Half full vs. half empty

Dr. Cleland likened the question of whom to treat with iron supplementation as a “glass half full versus half empty” clinical dilemma. “One approach is to give iron to everyone unless there’s evidence that they’re overloaded,” he said, “while the other is to withhold iron from everyone unless there’s evidence that they’re iron depleted.”

Recent evidence from the IRONMAN trial suggested that its patients with HF who received intravenous iron were less likely to be hospitalized for infections, particularly COVID-19, than a usual-care group. The treatment may also help reduce frailty.

“So should we be offering IV iron specifically to people considered iron deficient, or should we be ensuring that everyone over age 70 get iron supplements?” Dr. Cleland mused rhetorically. On a cautionary note, he added, perhaps iron supplementation will be harmful if it’s not necessary.

Dr. Cleland proposed “focusing for the moment on people who are iron deficient but investigating the possibility that we are being overly restrictive and should be giving iron to a much broader population.” That course, however, would require large population-based studies.

“We need more experience,” Dr. Cleland said, “to make sure that the benefits outweigh any risks before we can just give iron to everyone.”

Dr. Martens has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Abbott, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Vifor Pharma. Dr. Cleland declares grant support, support for travel, and personal honoraria from Pharmacosmos and Vifor. Disclosures for other authors are in the published report and editorial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL