User login

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

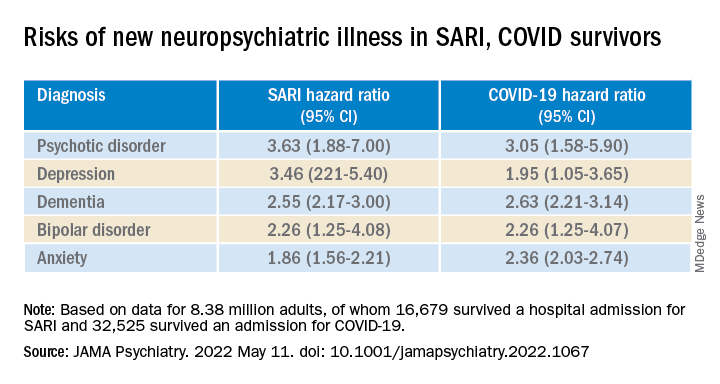

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

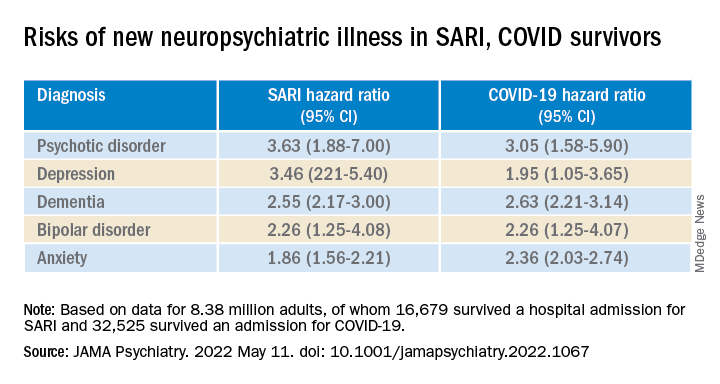

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

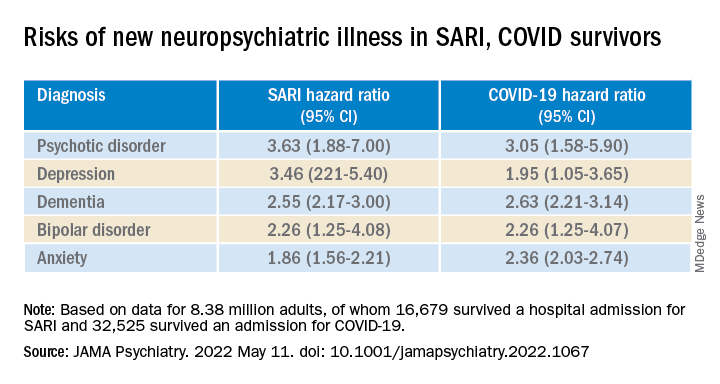

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.