User login

A 40-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, who was recently started on a diuretic, presents to the emergency department after a witnessed syncopal event. She reports a prodrome of lightheadedness, nausea, and darkening of her vision that occurred a few seconds after standing, followed by loss of consciousness. She had a complete, spontaneous recovery after 10 seconds, but upon arousal she noticed she had lost bladder control.

Her blood pressure is 120/80 mm Hg supine, 110/70 mm Hg sitting, and 90/60 mm Hg standing. She has no focal neurologic deficits. The cardiac examination is normal, without murmurs, and electrocardiography shows sinus tachycardia (heart rate 110 bpm) without other abnormalities. Results of laboratory testing are unremarkable.

Should you order neuroimaging to evaluate for syncope?

DEFINITIONS, CLASSIFICATIONS

Syncope is an abrupt loss of consciousness due to transient global cerebral hypoperfusion, with a concomitant loss of postural tone and rapid, spontaneous recovery.1 Recovery from syncope is characterized by immediate restoration of orientation and normal behavior, although the period after recovery may be accompanied by fatigue.2

The European Society of Cardiology2 has classified syncope into 3 main categories: reflex (neurally mediated) syncope, syncope due to orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac syncope. Determining the cause is critical, as this determines the prognosis.

KEYS TO THE EVALUATION

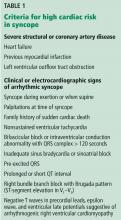

According to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the 2009 European Society of Cardiology guidelines, the evaluation of syncope should include a thorough history, taken from the patient and witnesses, and a complete physical examination. This can identify the cause of syncope in up to 50% of cases and differentiate between cardiac and noncardiac causes. Features that point to cardiac syncope include age older than 60, male sex, known heart disease, brief prodrome, syncope during exertion or when supine, first syncopal event, family history of sudden cardiac death, and abnormal physical examination.1

Features that suggest noncardiac syncope are young age; syncope only when standing; recurrent syncope; a prodrome of nausea, vomiting, and a warm sensation; and triggers such as dehydration, pain, distressful stimulus, cough, laugh micturition, defecation, and swallowing.1

Electrocardiography should follow the history and physical examination. When done at presentation, electrocardiography is diagnostic in only about 5% of cases. However, given the importance of the diagnosis, it remains an essential part of the initial evaluation of syncope.3

If a clear cause of syncope is identified at this point, no further workup is needed, and the cause of syncope should be addressed.1 If the cause is still unclear, the ACC/AHA guidelines recommend further evaluation based on the clinical presentation and risk stratification.

WHEN TO PURSUE ADDITIONAL TESTING

Routine use of additional testing is costly; tests should be ordered on the basis of their potential diagnostic and prognostic value. Additional evaluation should follow a stepwise approach and can include targeted blood work, autonomic nerve evaluation, tilt-table testing, transthoracic echocardiography, stress testing, electrocardiographic monitoring, and electrophysiologic testing.1

Syncope is rarely a manifestation of neurologic disease, yet 11% to 58% of patients with a first episode of uncomplicated syncope undergo extensive neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, electroencephalography (EEG), and carotid ultrasonography.4 Evidence suggests that routine neurologic testing is of limited value given its low diagnostic yield and high cost.

Epilepsy is the most common neurologic cause of loss of consciousness but is estimated to account for less than 5% of patients with syncope.5 A thorough and thoughtful neurologic history and examination is often enough to distinguish between syncope, convulsive syncope, epileptic convulsions, and pseudosyncope.

In syncope, the loss of consciousness usually occurs 30 seconds to several minutes after standing. It presents with or without a prodrome (warmth, palpitations, and diaphoresis) and can be relieved with supine positioning. True loss of consciousness usually lasts less than a minute and is accompanied by loss of postural tone, with little or no fatigue in the recovery period.6

Conversely, in convulsive syncope, the prodrome can include pallor and diaphoresis. Loss of consciousness lasts about 30 seconds but is accompanied by fixed gaze, upward eye deviation, nuchal rigidity, tonic spasms, myoclonic jerks, tonic-clonic convulsions, and oral automatisms.6

Pseudosyncope is characterized by a prodrome of lightheadedness, shortness of breath, chest pain, and tingling sensations, followed by episodes of apparent loss of consciousness that last longer than several minutes and occur multiple times a day. During these episodes, patients purposefully try to avoid trauma when they lose consciousness, and almost always keep their eyes closed, in contrast to syncopal episodes, when the eyes are open and glassy.7

ROLE OF ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

If the diagnosis remains unclear after the history and neurologic examination, EEG is recommended (class IIa, ie, reasonable, can be useful) during tilt-table testing, as it can help differentiate syncope, pseudosyncope, and epilepsy.1

In an epileptic convulsion, EEG shows epileptiform discharges, whereas in syncope, it shows diffuse brainwave slowing with delta waves and a flatline pattern. In pseudosyncope and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, EEG shows normal activity.8

Routine EEG is not recommended if there are no specific neurologic signs of epilepsy or if the history and neurologic examination indicate syncope or pseudosyncope.1

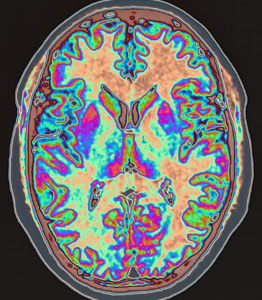

Structural brain disease does not typically present with transient global cerebral hypoperfusion resulting in syncope, so magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have a low diagnostic yield. Studies have revealed that for the 11% to 58% of patients who undergo neuroimaging, it establishes a diagnosis in only 0.2% to 1%.9 For this reason and in view of their high cost, these imaging tests should not be routinely ordered in the evaluation of syncope.4,10 Similarly, carotid artery imaging should not be routinely ordered if there is no focal neurologic finding suggesting unilateral ischemia.10

CASE CONTINUED

In our 40-year-old patient, the history suggests dehydration, as she recently started taking a diuretic. Thus, laboratory testing is reasonable.

Loss of bladder control is often interpreted as a red flag for neurologic disease, but syncope can often present with urinary incontinence. Urinary incontinence may also occur in epileptic seizure and in nonepileptic events such as syncope. A pooled analysis by Brigo et al11 determined that urinary incontinence had no value in distinguishing between epilepsy and syncope. Therefore, this physical finding should not incline the clinician to one diagnosis or the other.

Given our patient’s presentation, findings on physical examination, and absence of focal neurologic deficits, she should not undergo neuroimaging for syncope evaluation. The more likely cause of her syncope is orthostatic intolerance (orthostatic hypotension or vasovagal syncope) in the setting of intravascular volume depletion, likely secondary to diuretic use. Obtaining orthostatic vital signs is mandatory, and this confirms the diagnosis.

- Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70(5):e39–e110. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.003

- Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope; European Society of Cardiology (ESC); European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA); Heart Failure Association (HFA); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J 2009; 30(21):2631–2671. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

- Mehlsen J, Kaijer MN, Mehlsen AB. Autonomic and electrocardiographic changes in cardioinhibitory syncope. Europace 2008; 10(1):91–95. doi:10.1093/europace/eum237

- Goyal N, Donnino MW, Vachhani R, Bajwa R, Ahmad T, Otero R. The utility of head computed tomography in the emergency department evaluation of syncope. Intern Emerg Med 2006; 1(2):148–150. pmid:17111790

- Kapoor WN, Karpf M, Wieand S, Peterson JR, Levey GS. A prospective evaluation and follow-up of patients with syncope. N Engl J Med 1983; 309(4):197–204. doi:10.1056/NEJM198307283090401

- Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin 2015; 33(3):377–385. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2015.04.006

- Raj V, Rowe AA, Fleisch SB, Paranjape SY, Arain AM, Nicolson SE. Psychogenic pseudosyncope: diagnosis and management. Auton Neurosci 2014; 184:66–72. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2014.05.003

- Mecarelli O, Pulitano P, Vicenzini E, Vanacore N, Accornero N, De Marinis M. Observations on EEG patterns in neurally-mediated syncope: an inspective and quantitative study. Neurophysiol Clin 2004; 34(5):203–207. doi:10.1016/j.neucli.2004.09.004

- Johnson PC, Ammar H, Zohdy W, Fouda R, Govindu R. Yield of diagnostic tests and its impact on cost in adult patients with syncope presenting to a community hospital. South Med J 2014; 107(11):707–714. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000184

- Sclafani JJ, My J, Zacher LL, Eckart RE. Intensive education on evidence-based evaluation of syncope increases sudden death risk stratification but fails to reduce use of neuroimaging. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(13):1150–1154. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.205

- Brigo F, Nardone R Ausserer H, et al. The diagnostic value of urinary incontinence in the differential diagnosis of seizures. Seizure 2013; 22(2):85–90. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2012.10.011

A 40-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, who was recently started on a diuretic, presents to the emergency department after a witnessed syncopal event. She reports a prodrome of lightheadedness, nausea, and darkening of her vision that occurred a few seconds after standing, followed by loss of consciousness. She had a complete, spontaneous recovery after 10 seconds, but upon arousal she noticed she had lost bladder control.

Her blood pressure is 120/80 mm Hg supine, 110/70 mm Hg sitting, and 90/60 mm Hg standing. She has no focal neurologic deficits. The cardiac examination is normal, without murmurs, and electrocardiography shows sinus tachycardia (heart rate 110 bpm) without other abnormalities. Results of laboratory testing are unremarkable.

Should you order neuroimaging to evaluate for syncope?

DEFINITIONS, CLASSIFICATIONS

Syncope is an abrupt loss of consciousness due to transient global cerebral hypoperfusion, with a concomitant loss of postural tone and rapid, spontaneous recovery.1 Recovery from syncope is characterized by immediate restoration of orientation and normal behavior, although the period after recovery may be accompanied by fatigue.2

The European Society of Cardiology2 has classified syncope into 3 main categories: reflex (neurally mediated) syncope, syncope due to orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac syncope. Determining the cause is critical, as this determines the prognosis.

KEYS TO THE EVALUATION

According to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the 2009 European Society of Cardiology guidelines, the evaluation of syncope should include a thorough history, taken from the patient and witnesses, and a complete physical examination. This can identify the cause of syncope in up to 50% of cases and differentiate between cardiac and noncardiac causes. Features that point to cardiac syncope include age older than 60, male sex, known heart disease, brief prodrome, syncope during exertion or when supine, first syncopal event, family history of sudden cardiac death, and abnormal physical examination.1

Features that suggest noncardiac syncope are young age; syncope only when standing; recurrent syncope; a prodrome of nausea, vomiting, and a warm sensation; and triggers such as dehydration, pain, distressful stimulus, cough, laugh micturition, defecation, and swallowing.1

Electrocardiography should follow the history and physical examination. When done at presentation, electrocardiography is diagnostic in only about 5% of cases. However, given the importance of the diagnosis, it remains an essential part of the initial evaluation of syncope.3

If a clear cause of syncope is identified at this point, no further workup is needed, and the cause of syncope should be addressed.1 If the cause is still unclear, the ACC/AHA guidelines recommend further evaluation based on the clinical presentation and risk stratification.

WHEN TO PURSUE ADDITIONAL TESTING

Routine use of additional testing is costly; tests should be ordered on the basis of their potential diagnostic and prognostic value. Additional evaluation should follow a stepwise approach and can include targeted blood work, autonomic nerve evaluation, tilt-table testing, transthoracic echocardiography, stress testing, electrocardiographic monitoring, and electrophysiologic testing.1

Syncope is rarely a manifestation of neurologic disease, yet 11% to 58% of patients with a first episode of uncomplicated syncope undergo extensive neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, electroencephalography (EEG), and carotid ultrasonography.4 Evidence suggests that routine neurologic testing is of limited value given its low diagnostic yield and high cost.

Epilepsy is the most common neurologic cause of loss of consciousness but is estimated to account for less than 5% of patients with syncope.5 A thorough and thoughtful neurologic history and examination is often enough to distinguish between syncope, convulsive syncope, epileptic convulsions, and pseudosyncope.

In syncope, the loss of consciousness usually occurs 30 seconds to several minutes after standing. It presents with or without a prodrome (warmth, palpitations, and diaphoresis) and can be relieved with supine positioning. True loss of consciousness usually lasts less than a minute and is accompanied by loss of postural tone, with little or no fatigue in the recovery period.6

Conversely, in convulsive syncope, the prodrome can include pallor and diaphoresis. Loss of consciousness lasts about 30 seconds but is accompanied by fixed gaze, upward eye deviation, nuchal rigidity, tonic spasms, myoclonic jerks, tonic-clonic convulsions, and oral automatisms.6

Pseudosyncope is characterized by a prodrome of lightheadedness, shortness of breath, chest pain, and tingling sensations, followed by episodes of apparent loss of consciousness that last longer than several minutes and occur multiple times a day. During these episodes, patients purposefully try to avoid trauma when they lose consciousness, and almost always keep their eyes closed, in contrast to syncopal episodes, when the eyes are open and glassy.7

ROLE OF ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

If the diagnosis remains unclear after the history and neurologic examination, EEG is recommended (class IIa, ie, reasonable, can be useful) during tilt-table testing, as it can help differentiate syncope, pseudosyncope, and epilepsy.1

In an epileptic convulsion, EEG shows epileptiform discharges, whereas in syncope, it shows diffuse brainwave slowing with delta waves and a flatline pattern. In pseudosyncope and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, EEG shows normal activity.8

Routine EEG is not recommended if there are no specific neurologic signs of epilepsy or if the history and neurologic examination indicate syncope or pseudosyncope.1

Structural brain disease does not typically present with transient global cerebral hypoperfusion resulting in syncope, so magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have a low diagnostic yield. Studies have revealed that for the 11% to 58% of patients who undergo neuroimaging, it establishes a diagnosis in only 0.2% to 1%.9 For this reason and in view of their high cost, these imaging tests should not be routinely ordered in the evaluation of syncope.4,10 Similarly, carotid artery imaging should not be routinely ordered if there is no focal neurologic finding suggesting unilateral ischemia.10

CASE CONTINUED

In our 40-year-old patient, the history suggests dehydration, as she recently started taking a diuretic. Thus, laboratory testing is reasonable.

Loss of bladder control is often interpreted as a red flag for neurologic disease, but syncope can often present with urinary incontinence. Urinary incontinence may also occur in epileptic seizure and in nonepileptic events such as syncope. A pooled analysis by Brigo et al11 determined that urinary incontinence had no value in distinguishing between epilepsy and syncope. Therefore, this physical finding should not incline the clinician to one diagnosis or the other.

Given our patient’s presentation, findings on physical examination, and absence of focal neurologic deficits, she should not undergo neuroimaging for syncope evaluation. The more likely cause of her syncope is orthostatic intolerance (orthostatic hypotension or vasovagal syncope) in the setting of intravascular volume depletion, likely secondary to diuretic use. Obtaining orthostatic vital signs is mandatory, and this confirms the diagnosis.

A 40-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, who was recently started on a diuretic, presents to the emergency department after a witnessed syncopal event. She reports a prodrome of lightheadedness, nausea, and darkening of her vision that occurred a few seconds after standing, followed by loss of consciousness. She had a complete, spontaneous recovery after 10 seconds, but upon arousal she noticed she had lost bladder control.

Her blood pressure is 120/80 mm Hg supine, 110/70 mm Hg sitting, and 90/60 mm Hg standing. She has no focal neurologic deficits. The cardiac examination is normal, without murmurs, and electrocardiography shows sinus tachycardia (heart rate 110 bpm) without other abnormalities. Results of laboratory testing are unremarkable.

Should you order neuroimaging to evaluate for syncope?

DEFINITIONS, CLASSIFICATIONS

Syncope is an abrupt loss of consciousness due to transient global cerebral hypoperfusion, with a concomitant loss of postural tone and rapid, spontaneous recovery.1 Recovery from syncope is characterized by immediate restoration of orientation and normal behavior, although the period after recovery may be accompanied by fatigue.2

The European Society of Cardiology2 has classified syncope into 3 main categories: reflex (neurally mediated) syncope, syncope due to orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac syncope. Determining the cause is critical, as this determines the prognosis.

KEYS TO THE EVALUATION

According to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the 2009 European Society of Cardiology guidelines, the evaluation of syncope should include a thorough history, taken from the patient and witnesses, and a complete physical examination. This can identify the cause of syncope in up to 50% of cases and differentiate between cardiac and noncardiac causes. Features that point to cardiac syncope include age older than 60, male sex, known heart disease, brief prodrome, syncope during exertion or when supine, first syncopal event, family history of sudden cardiac death, and abnormal physical examination.1

Features that suggest noncardiac syncope are young age; syncope only when standing; recurrent syncope; a prodrome of nausea, vomiting, and a warm sensation; and triggers such as dehydration, pain, distressful stimulus, cough, laugh micturition, defecation, and swallowing.1

Electrocardiography should follow the history and physical examination. When done at presentation, electrocardiography is diagnostic in only about 5% of cases. However, given the importance of the diagnosis, it remains an essential part of the initial evaluation of syncope.3

If a clear cause of syncope is identified at this point, no further workup is needed, and the cause of syncope should be addressed.1 If the cause is still unclear, the ACC/AHA guidelines recommend further evaluation based on the clinical presentation and risk stratification.

WHEN TO PURSUE ADDITIONAL TESTING

Routine use of additional testing is costly; tests should be ordered on the basis of their potential diagnostic and prognostic value. Additional evaluation should follow a stepwise approach and can include targeted blood work, autonomic nerve evaluation, tilt-table testing, transthoracic echocardiography, stress testing, electrocardiographic monitoring, and electrophysiologic testing.1

Syncope is rarely a manifestation of neurologic disease, yet 11% to 58% of patients with a first episode of uncomplicated syncope undergo extensive neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, electroencephalography (EEG), and carotid ultrasonography.4 Evidence suggests that routine neurologic testing is of limited value given its low diagnostic yield and high cost.

Epilepsy is the most common neurologic cause of loss of consciousness but is estimated to account for less than 5% of patients with syncope.5 A thorough and thoughtful neurologic history and examination is often enough to distinguish between syncope, convulsive syncope, epileptic convulsions, and pseudosyncope.

In syncope, the loss of consciousness usually occurs 30 seconds to several minutes after standing. It presents with or without a prodrome (warmth, palpitations, and diaphoresis) and can be relieved with supine positioning. True loss of consciousness usually lasts less than a minute and is accompanied by loss of postural tone, with little or no fatigue in the recovery period.6

Conversely, in convulsive syncope, the prodrome can include pallor and diaphoresis. Loss of consciousness lasts about 30 seconds but is accompanied by fixed gaze, upward eye deviation, nuchal rigidity, tonic spasms, myoclonic jerks, tonic-clonic convulsions, and oral automatisms.6

Pseudosyncope is characterized by a prodrome of lightheadedness, shortness of breath, chest pain, and tingling sensations, followed by episodes of apparent loss of consciousness that last longer than several minutes and occur multiple times a day. During these episodes, patients purposefully try to avoid trauma when they lose consciousness, and almost always keep their eyes closed, in contrast to syncopal episodes, when the eyes are open and glassy.7

ROLE OF ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

If the diagnosis remains unclear after the history and neurologic examination, EEG is recommended (class IIa, ie, reasonable, can be useful) during tilt-table testing, as it can help differentiate syncope, pseudosyncope, and epilepsy.1

In an epileptic convulsion, EEG shows epileptiform discharges, whereas in syncope, it shows diffuse brainwave slowing with delta waves and a flatline pattern. In pseudosyncope and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, EEG shows normal activity.8

Routine EEG is not recommended if there are no specific neurologic signs of epilepsy or if the history and neurologic examination indicate syncope or pseudosyncope.1

Structural brain disease does not typically present with transient global cerebral hypoperfusion resulting in syncope, so magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have a low diagnostic yield. Studies have revealed that for the 11% to 58% of patients who undergo neuroimaging, it establishes a diagnosis in only 0.2% to 1%.9 For this reason and in view of their high cost, these imaging tests should not be routinely ordered in the evaluation of syncope.4,10 Similarly, carotid artery imaging should not be routinely ordered if there is no focal neurologic finding suggesting unilateral ischemia.10

CASE CONTINUED

In our 40-year-old patient, the history suggests dehydration, as she recently started taking a diuretic. Thus, laboratory testing is reasonable.

Loss of bladder control is often interpreted as a red flag for neurologic disease, but syncope can often present with urinary incontinence. Urinary incontinence may also occur in epileptic seizure and in nonepileptic events such as syncope. A pooled analysis by Brigo et al11 determined that urinary incontinence had no value in distinguishing between epilepsy and syncope. Therefore, this physical finding should not incline the clinician to one diagnosis or the other.

Given our patient’s presentation, findings on physical examination, and absence of focal neurologic deficits, she should not undergo neuroimaging for syncope evaluation. The more likely cause of her syncope is orthostatic intolerance (orthostatic hypotension or vasovagal syncope) in the setting of intravascular volume depletion, likely secondary to diuretic use. Obtaining orthostatic vital signs is mandatory, and this confirms the diagnosis.

- Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70(5):e39–e110. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.003

- Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope; European Society of Cardiology (ESC); European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA); Heart Failure Association (HFA); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J 2009; 30(21):2631–2671. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

- Mehlsen J, Kaijer MN, Mehlsen AB. Autonomic and electrocardiographic changes in cardioinhibitory syncope. Europace 2008; 10(1):91–95. doi:10.1093/europace/eum237

- Goyal N, Donnino MW, Vachhani R, Bajwa R, Ahmad T, Otero R. The utility of head computed tomography in the emergency department evaluation of syncope. Intern Emerg Med 2006; 1(2):148–150. pmid:17111790

- Kapoor WN, Karpf M, Wieand S, Peterson JR, Levey GS. A prospective evaluation and follow-up of patients with syncope. N Engl J Med 1983; 309(4):197–204. doi:10.1056/NEJM198307283090401

- Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin 2015; 33(3):377–385. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2015.04.006

- Raj V, Rowe AA, Fleisch SB, Paranjape SY, Arain AM, Nicolson SE. Psychogenic pseudosyncope: diagnosis and management. Auton Neurosci 2014; 184:66–72. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2014.05.003

- Mecarelli O, Pulitano P, Vicenzini E, Vanacore N, Accornero N, De Marinis M. Observations on EEG patterns in neurally-mediated syncope: an inspective and quantitative study. Neurophysiol Clin 2004; 34(5):203–207. doi:10.1016/j.neucli.2004.09.004

- Johnson PC, Ammar H, Zohdy W, Fouda R, Govindu R. Yield of diagnostic tests and its impact on cost in adult patients with syncope presenting to a community hospital. South Med J 2014; 107(11):707–714. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000184

- Sclafani JJ, My J, Zacher LL, Eckart RE. Intensive education on evidence-based evaluation of syncope increases sudden death risk stratification but fails to reduce use of neuroimaging. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(13):1150–1154. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.205

- Brigo F, Nardone R Ausserer H, et al. The diagnostic value of urinary incontinence in the differential diagnosis of seizures. Seizure 2013; 22(2):85–90. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2012.10.011

- Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70(5):e39–e110. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.003

- Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope; European Society of Cardiology (ESC); European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA); Heart Failure Association (HFA); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J 2009; 30(21):2631–2671. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

- Mehlsen J, Kaijer MN, Mehlsen AB. Autonomic and electrocardiographic changes in cardioinhibitory syncope. Europace 2008; 10(1):91–95. doi:10.1093/europace/eum237

- Goyal N, Donnino MW, Vachhani R, Bajwa R, Ahmad T, Otero R. The utility of head computed tomography in the emergency department evaluation of syncope. Intern Emerg Med 2006; 1(2):148–150. pmid:17111790

- Kapoor WN, Karpf M, Wieand S, Peterson JR, Levey GS. A prospective evaluation and follow-up of patients with syncope. N Engl J Med 1983; 309(4):197–204. doi:10.1056/NEJM198307283090401

- Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin 2015; 33(3):377–385. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2015.04.006

- Raj V, Rowe AA, Fleisch SB, Paranjape SY, Arain AM, Nicolson SE. Psychogenic pseudosyncope: diagnosis and management. Auton Neurosci 2014; 184:66–72. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2014.05.003

- Mecarelli O, Pulitano P, Vicenzini E, Vanacore N, Accornero N, De Marinis M. Observations on EEG patterns in neurally-mediated syncope: an inspective and quantitative study. Neurophysiol Clin 2004; 34(5):203–207. doi:10.1016/j.neucli.2004.09.004

- Johnson PC, Ammar H, Zohdy W, Fouda R, Govindu R. Yield of diagnostic tests and its impact on cost in adult patients with syncope presenting to a community hospital. South Med J 2014; 107(11):707–714. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000184

- Sclafani JJ, My J, Zacher LL, Eckart RE. Intensive education on evidence-based evaluation of syncope increases sudden death risk stratification but fails to reduce use of neuroimaging. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170(13):1150–1154. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.205

- Brigo F, Nardone R Ausserer H, et al. The diagnostic value of urinary incontinence in the differential diagnosis of seizures. Seizure 2013; 22(2):85–90. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2012.10.011