User login

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare but lifethreatening soft-tissue infection. Its presentation is characterized by rapidly spreading inflammation and resultant death—both of the surrounding soft tissue and fascial planes. Prompt recognition and aggressive treatment are paramount to avoid fatality, and appropriate management in the ED is essential to a successful outcome. As the following case illustrates, a high index of suspicion and multidisciplinary approach, including applicable imaging studies, result in timely diagnosis and treatment.

Case

A 60-year-old woman with a medical history of childhood Lyme disease, asthma, high cholesterol, and seasonal allergies, presented to the ED with a 3-day history of left hip and thigh pain, general malaise, decreased appetite, nausea, myalgia, and increased lethargy. She reported difficulty with weight-bearing on her left leg but denied any recent leg trauma or falls. Patient also had a 3-year history of intermittent hip pain, which she treated with ibuprofen. Three weeks prior to presentation, she had undergone an invasive dental procedure in preparation for a root canal. She later developed a fever of 102° F and had taken ibuprofen two-and-a-half hours prior to arrival at our institution.

Initial vital signs on physical examination were: blood pressure (BP) 71/37 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 98 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; temperature, 98.5° F. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Patient was awake and alert but extremely pale and sluggish. Her head, ears, nose, and throat; pulmonary; cardiac; and abdominal examinations were normal. On physical examination, the skin overlying her left hip and thigh was grossly unremarkable, and no previous incision sites or areas of trauma were observed throughout the left lower extremity. No obvious signs of infection or erythema were noted; however, an area of warmth was felt on the lateral aspect of the left thigh but did not extend beyond the knee. Patient was able to flex her left hip approximately 30° and only complained of pain to the lateral aspect of the upper leg with passive internal and external rotation. Heel strike was negative, and knee examination was negative for pathology. The right lower extremity was unremarkable.

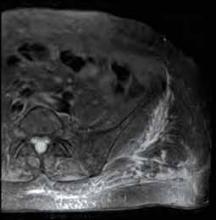

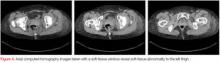

A plain radiograph of the pelvis and left hip showed soft-tissue swelling but no bony pathology or fracture (Figure 1). There was no visual evidence of subcutaneous gas, and chest radiograph was negative for any active disease. Based on the clinical picture of septic shock due to possible septic arthritis, emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left hip and thigh was performed without contrast (Figures 2 and 3). Extensive edema was noted diffusely throughout patient’s left gluteus medius muscle and vastus latera lis muscle; no loculated fluid collection was noted. The edema was concentrated around the proximal left thigh but extended to the level of the knee. The left hip was free of any fluid collection, ruling-out septic arthritis. Based on these MRI findings, a computed tomography scan was ordered, which showed no fluid collection in the pelvis and abdomen (Figure 4).

Patient was continued on an antibiotic regimen of IV vancomycin, clindamycin, and piperacillin-tazobactam. Vasopressor support was gradually reduced and respiratory support weaned until both were finally discontinued on postoperative day 2. Soon thereafter, she was transferred to the surgical floor. Negative pressure wound vacuum-assisted closure therapy was applied to the left thigh and was maintained for one week.

The operative cultures were positive for group A Streptococcus (GAS) pyogenes. Upon discharge, antibiotic regimen was adjusted and limited to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate for 14 days until completion. After a 2-week hospital stay, patient was transferred to an acute rehabilitation facility in stable condition and remained there for one week. Follow up was maintained for a total of 6 months, during which time she had no lasting effects from either illness or resultant interventions other than cosmetic concerns from the surgical wounds. In a follow-up phone discussion with patient 10 months after recovery, she reported that she had returned to work as a registered nurse and had been without any functional disability or discomfort.

Discussion

Originally described by Hippocrates in the 5th century as a complication of erysipelas, necrotizing fasciitis later became known as the “malignant ulcer.” It was subsequently described in the United States in 1871 as “hospital gangrene” by Confederate surgeon Joseph Jones.1-3 In 1952, the name was later modified to necrotizing fasciitis by Wilson.4

Today, necrotizing fasciitis is an uncommon disease process, yet one that must be recognized and treated immediately. If not dealt with promptly and aggressively, the virulent and toxin-producing bacteria— most commonly GAS pyogenes— will cause severe systemic toxicity and may lead to death.5

Incidences and Outcomes

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 9,000 to 11,500 cases of invasive GAS disease occur each year in the United States, resulting in approximately 1,000 to 1,800 deaths annually. Necrotizing fasciitis comprises an average of 6% to 7% (540- 805) of these invasive cases per year.6

The incidence of necrotizing fasciitis rose sharply in the mid-1980s to the early 1990s but has remained steady over the past 10 years, with 2012 CDC statistics reporting 72 cases per 32,777,740 persons through its voluntary surveillance program. This extrapolates to an estimated 686 cases of GAS-associated necrotizing fasciitis in the United States, with a reported mortality rate of 20% to 25%.7

The highest incidence of disease occurs in the elderly and in patients with diabetes, immunosuppression, and peripheral vascular disease. In children, varicella infection is a known risk factor.8

Other risk factors include obesity, alcohol use, malnutrition, and smoking, as well as corticosteroid use and chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Despite the large number of predisposing factors that have been identified, half of all cases of necrotizing fasciitis occur in healthy individuals.9-14

Etiology

Necrotizing fasciitis is thought to be caused by at least two distinct bacteriologic entities. Type I is considered polymicrobial, with Bacteriodes, Clostridium, and Peptostreptococcus, in combination with anaerobic Streptococcus (other than GAS) and Enterobacteriaceae (eg, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella), being the most common infecting species. Type II causative agents include GAS and other β-hemolytic streptococci— alone or with other species of Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin- resistant S aureus.8 In rare instances, the causative agent is fungal.

Treatment

In a review of patient medical records, Wong et al15 demonstrated that prompt recognition and surgical management of necrotizing fasciitis (ie, within 24 hours of presentation) resulted in improved outcomes. Since the particular causative agent of necrotizing fasciitis in each case is usually unknown, initial treatment should include broad-spectrum IV antibiotics— which are active against grampositive, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria—with special consideration for GAS and Clostridium (Table). It is not recommended that initial empiric therapy include antifungals. In this case, the patient was in the OR within 10 hours from presentation, was started immediately on antibiotic regimens for hospital-specific sepsis, and was given appropriate resuscitative measures.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is mentioned in the literature as an adjunct to surgery and antibiotics in the treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. Acting as a bactericidal/ bacteriostatic agent against anaerobic bacteria by increasing formation of free oxygen radicals, this therapy is thought to restore the bacterial killing capacity of leukocytes in a hypoxic wound by increasing oxygen tension. Treatment with hyperbaric oxygen may also better define necrotic tissue, facilitating more precise amputation and debridement. Although there are no randomized controlled studies in humans, several authors have shown a reduction in mortality and morbidity with the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, in conjunction with early antibiotic and surgical treatment, in animal models and in retrospective studies of patients. 19 When available, hyperbaric oxygen can be initiated once antibiotics have been started and debridement has been performed. The use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy should not delay definitive surgical debridement.

Our case demonstrates a true surgical emergency—one that was appropriately managed with a multidisciplinary team approach. A high index of suspicion by the examining ED staff and surgical consultants led to supportive measures to maintain the patient’s vital signs and ultimately her life. Despite having no clear etiology for the cause of necrotizing fasciitis, we believe it may have resulted from the patient’s prior dental work or chronic NSAID use. Although there is no causal relationship, reports suggest that NSAIDs may prevent prompt recognition and accelerate the infection by altering its initial presentation.20 The patient reported no recent use of anti-inflammatory medication in association with her pain—only for fever.

This report also underscores the importance of urgent MRI in the ED setting. In addition to helping exclude other diagnoses involving the hip joint, MRI provided a roadmap for debridement of active infection. Moreover, the test eliminated the need to explore the left hip joint as well as the risk of seeding a sterile space.21

Conclusion

- Descamps V, Aitken J, Lee MG. Hippocrates on necrotising fasciitis [letter]. Lancet. 1994; 344(8921):556.

- Jones J. Investigations upon the nature, causes, and treatments of hospital gangrene as it prevailed in the Confederate armies 1861-1865. In: Hastings HF, ed. US Sanitary Commission, Surgical memoirs of the War of Rebellion. New York, New York: Riverside; 1871:146-170.

- Loudon I. Necrotising fasciitis, hospital gangrene, and phagedena. Lancet. 1994;344(8934):1416-1419.

- Wilson B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Am Surg. 1952;18(4):416-431.

- Green RJ, Dafoe DC, Raffin TA. Necrotizing fasciitis. Chest. 1996;110(1):219-229.

- Necrotizing fasciitis: A Rare Disease, Especially for the Healthy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/Features/NecrotizingFasciitis/. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- ABCs report: group A Streptococcus, 2012-provisional. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs): Emerging Infections Program Network. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/gas12.html. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- Stevens, DL, Baddour, LM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. UpToDate Web site. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/necrotizing-soft-tissue-infections. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- Bellapianta J, Ljungquist K, Tobin E, Uhl R. Necrotizing Fasciitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(3):174-182.

- Childers BJ, Potyondy LD, Nachreiner R, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: A fourteen-year retrospective study of 163 consecutive patients. Am Surg. 2002;68(2):109-116.

- Dufel S, Martino M. Simple cellulitis or a more serious infection? J Fam Pract. 2006;55(5):396-400.

- Lamagni TL, Neal S, Keshishian C, et al. Severe Streptococcus pyogenes infections, United Kingdom, 2003-2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(2):202-209.

- Sharkawy A, Low D, Saginur R, et al. Severe group A streptococcal soft-tissue infections in Ontario: 1992-1996. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(4):454-460.

- Sudarsky LA, Laschinger JC, Coppa GF, Spencer FC. Improved results from a standardized approach in treating patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Ann Surg. 1987; 206(5):661-665.

- Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(8):1454-1460.

- Khan, AT, Tahmeedullah, Obajdullah. Treatment of necrotizing fasciitis with quinolones. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2003;13(11): 649-652.

- Schwartz, RA. Necrotizing fasciitis empiric therapy. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/

article/2012058-overview. Accessed January 2, 2014. - Stevens, DL, Bisno, AL, Chambers, HF, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1373-1406.

- Mechem, CC, Manaker, S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. UpToDate Web site. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hyperbaric-oxygen-therapy?source=search_result&search=Mechem%2C+C.+Crawford%2C++Manaker%2C+Scott.+Hyperbaric+Oxygen+Therapy.&selectedTitle=8%7E91. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- Aronoff DM, Bloch KC. Assessing the relationship between the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A streptococcus. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82(4):225-235.

- Tang WM, Wong JW, Wong LL, Leong JC. Streptococcal necrotizing myositis: the role of magnetic resonance imaging. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(11):1723-1726.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare but lifethreatening soft-tissue infection. Its presentation is characterized by rapidly spreading inflammation and resultant death—both of the surrounding soft tissue and fascial planes. Prompt recognition and aggressive treatment are paramount to avoid fatality, and appropriate management in the ED is essential to a successful outcome. As the following case illustrates, a high index of suspicion and multidisciplinary approach, including applicable imaging studies, result in timely diagnosis and treatment.

Case

A 60-year-old woman with a medical history of childhood Lyme disease, asthma, high cholesterol, and seasonal allergies, presented to the ED with a 3-day history of left hip and thigh pain, general malaise, decreased appetite, nausea, myalgia, and increased lethargy. She reported difficulty with weight-bearing on her left leg but denied any recent leg trauma or falls. Patient also had a 3-year history of intermittent hip pain, which she treated with ibuprofen. Three weeks prior to presentation, she had undergone an invasive dental procedure in preparation for a root canal. She later developed a fever of 102° F and had taken ibuprofen two-and-a-half hours prior to arrival at our institution.

Initial vital signs on physical examination were: blood pressure (BP) 71/37 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 98 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; temperature, 98.5° F. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Patient was awake and alert but extremely pale and sluggish. Her head, ears, nose, and throat; pulmonary; cardiac; and abdominal examinations were normal. On physical examination, the skin overlying her left hip and thigh was grossly unremarkable, and no previous incision sites or areas of trauma were observed throughout the left lower extremity. No obvious signs of infection or erythema were noted; however, an area of warmth was felt on the lateral aspect of the left thigh but did not extend beyond the knee. Patient was able to flex her left hip approximately 30° and only complained of pain to the lateral aspect of the upper leg with passive internal and external rotation. Heel strike was negative, and knee examination was negative for pathology. The right lower extremity was unremarkable.

A plain radiograph of the pelvis and left hip showed soft-tissue swelling but no bony pathology or fracture (Figure 1). There was no visual evidence of subcutaneous gas, and chest radiograph was negative for any active disease. Based on the clinical picture of septic shock due to possible septic arthritis, emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left hip and thigh was performed without contrast (Figures 2 and 3). Extensive edema was noted diffusely throughout patient’s left gluteus medius muscle and vastus latera lis muscle; no loculated fluid collection was noted. The edema was concentrated around the proximal left thigh but extended to the level of the knee. The left hip was free of any fluid collection, ruling-out septic arthritis. Based on these MRI findings, a computed tomography scan was ordered, which showed no fluid collection in the pelvis and abdomen (Figure 4).

Patient was continued on an antibiotic regimen of IV vancomycin, clindamycin, and piperacillin-tazobactam. Vasopressor support was gradually reduced and respiratory support weaned until both were finally discontinued on postoperative day 2. Soon thereafter, she was transferred to the surgical floor. Negative pressure wound vacuum-assisted closure therapy was applied to the left thigh and was maintained for one week.

The operative cultures were positive for group A Streptococcus (GAS) pyogenes. Upon discharge, antibiotic regimen was adjusted and limited to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate for 14 days until completion. After a 2-week hospital stay, patient was transferred to an acute rehabilitation facility in stable condition and remained there for one week. Follow up was maintained for a total of 6 months, during which time she had no lasting effects from either illness or resultant interventions other than cosmetic concerns from the surgical wounds. In a follow-up phone discussion with patient 10 months after recovery, she reported that she had returned to work as a registered nurse and had been without any functional disability or discomfort.

Discussion

Originally described by Hippocrates in the 5th century as a complication of erysipelas, necrotizing fasciitis later became known as the “malignant ulcer.” It was subsequently described in the United States in 1871 as “hospital gangrene” by Confederate surgeon Joseph Jones.1-3 In 1952, the name was later modified to necrotizing fasciitis by Wilson.4

Today, necrotizing fasciitis is an uncommon disease process, yet one that must be recognized and treated immediately. If not dealt with promptly and aggressively, the virulent and toxin-producing bacteria— most commonly GAS pyogenes— will cause severe systemic toxicity and may lead to death.5

Incidences and Outcomes

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 9,000 to 11,500 cases of invasive GAS disease occur each year in the United States, resulting in approximately 1,000 to 1,800 deaths annually. Necrotizing fasciitis comprises an average of 6% to 7% (540- 805) of these invasive cases per year.6

The incidence of necrotizing fasciitis rose sharply in the mid-1980s to the early 1990s but has remained steady over the past 10 years, with 2012 CDC statistics reporting 72 cases per 32,777,740 persons through its voluntary surveillance program. This extrapolates to an estimated 686 cases of GAS-associated necrotizing fasciitis in the United States, with a reported mortality rate of 20% to 25%.7

The highest incidence of disease occurs in the elderly and in patients with diabetes, immunosuppression, and peripheral vascular disease. In children, varicella infection is a known risk factor.8

Other risk factors include obesity, alcohol use, malnutrition, and smoking, as well as corticosteroid use and chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Despite the large number of predisposing factors that have been identified, half of all cases of necrotizing fasciitis occur in healthy individuals.9-14

Etiology

Necrotizing fasciitis is thought to be caused by at least two distinct bacteriologic entities. Type I is considered polymicrobial, with Bacteriodes, Clostridium, and Peptostreptococcus, in combination with anaerobic Streptococcus (other than GAS) and Enterobacteriaceae (eg, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella), being the most common infecting species. Type II causative agents include GAS and other β-hemolytic streptococci— alone or with other species of Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin- resistant S aureus.8 In rare instances, the causative agent is fungal.

Treatment

In a review of patient medical records, Wong et al15 demonstrated that prompt recognition and surgical management of necrotizing fasciitis (ie, within 24 hours of presentation) resulted in improved outcomes. Since the particular causative agent of necrotizing fasciitis in each case is usually unknown, initial treatment should include broad-spectrum IV antibiotics— which are active against grampositive, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria—with special consideration for GAS and Clostridium (Table). It is not recommended that initial empiric therapy include antifungals. In this case, the patient was in the OR within 10 hours from presentation, was started immediately on antibiotic regimens for hospital-specific sepsis, and was given appropriate resuscitative measures.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is mentioned in the literature as an adjunct to surgery and antibiotics in the treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. Acting as a bactericidal/ bacteriostatic agent against anaerobic bacteria by increasing formation of free oxygen radicals, this therapy is thought to restore the bacterial killing capacity of leukocytes in a hypoxic wound by increasing oxygen tension. Treatment with hyperbaric oxygen may also better define necrotic tissue, facilitating more precise amputation and debridement. Although there are no randomized controlled studies in humans, several authors have shown a reduction in mortality and morbidity with the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, in conjunction with early antibiotic and surgical treatment, in animal models and in retrospective studies of patients. 19 When available, hyperbaric oxygen can be initiated once antibiotics have been started and debridement has been performed. The use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy should not delay definitive surgical debridement.

Our case demonstrates a true surgical emergency—one that was appropriately managed with a multidisciplinary team approach. A high index of suspicion by the examining ED staff and surgical consultants led to supportive measures to maintain the patient’s vital signs and ultimately her life. Despite having no clear etiology for the cause of necrotizing fasciitis, we believe it may have resulted from the patient’s prior dental work or chronic NSAID use. Although there is no causal relationship, reports suggest that NSAIDs may prevent prompt recognition and accelerate the infection by altering its initial presentation.20 The patient reported no recent use of anti-inflammatory medication in association with her pain—only for fever.

This report also underscores the importance of urgent MRI in the ED setting. In addition to helping exclude other diagnoses involving the hip joint, MRI provided a roadmap for debridement of active infection. Moreover, the test eliminated the need to explore the left hip joint as well as the risk of seeding a sterile space.21

Conclusion

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare but lifethreatening soft-tissue infection. Its presentation is characterized by rapidly spreading inflammation and resultant death—both of the surrounding soft tissue and fascial planes. Prompt recognition and aggressive treatment are paramount to avoid fatality, and appropriate management in the ED is essential to a successful outcome. As the following case illustrates, a high index of suspicion and multidisciplinary approach, including applicable imaging studies, result in timely diagnosis and treatment.

Case

A 60-year-old woman with a medical history of childhood Lyme disease, asthma, high cholesterol, and seasonal allergies, presented to the ED with a 3-day history of left hip and thigh pain, general malaise, decreased appetite, nausea, myalgia, and increased lethargy. She reported difficulty with weight-bearing on her left leg but denied any recent leg trauma or falls. Patient also had a 3-year history of intermittent hip pain, which she treated with ibuprofen. Three weeks prior to presentation, she had undergone an invasive dental procedure in preparation for a root canal. She later developed a fever of 102° F and had taken ibuprofen two-and-a-half hours prior to arrival at our institution.

Initial vital signs on physical examination were: blood pressure (BP) 71/37 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 98 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; temperature, 98.5° F. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Patient was awake and alert but extremely pale and sluggish. Her head, ears, nose, and throat; pulmonary; cardiac; and abdominal examinations were normal. On physical examination, the skin overlying her left hip and thigh was grossly unremarkable, and no previous incision sites or areas of trauma were observed throughout the left lower extremity. No obvious signs of infection or erythema were noted; however, an area of warmth was felt on the lateral aspect of the left thigh but did not extend beyond the knee. Patient was able to flex her left hip approximately 30° and only complained of pain to the lateral aspect of the upper leg with passive internal and external rotation. Heel strike was negative, and knee examination was negative for pathology. The right lower extremity was unremarkable.

A plain radiograph of the pelvis and left hip showed soft-tissue swelling but no bony pathology or fracture (Figure 1). There was no visual evidence of subcutaneous gas, and chest radiograph was negative for any active disease. Based on the clinical picture of septic shock due to possible septic arthritis, emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left hip and thigh was performed without contrast (Figures 2 and 3). Extensive edema was noted diffusely throughout patient’s left gluteus medius muscle and vastus latera lis muscle; no loculated fluid collection was noted. The edema was concentrated around the proximal left thigh but extended to the level of the knee. The left hip was free of any fluid collection, ruling-out septic arthritis. Based on these MRI findings, a computed tomography scan was ordered, which showed no fluid collection in the pelvis and abdomen (Figure 4).

Patient was continued on an antibiotic regimen of IV vancomycin, clindamycin, and piperacillin-tazobactam. Vasopressor support was gradually reduced and respiratory support weaned until both were finally discontinued on postoperative day 2. Soon thereafter, she was transferred to the surgical floor. Negative pressure wound vacuum-assisted closure therapy was applied to the left thigh and was maintained for one week.

The operative cultures were positive for group A Streptococcus (GAS) pyogenes. Upon discharge, antibiotic regimen was adjusted and limited to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate for 14 days until completion. After a 2-week hospital stay, patient was transferred to an acute rehabilitation facility in stable condition and remained there for one week. Follow up was maintained for a total of 6 months, during which time she had no lasting effects from either illness or resultant interventions other than cosmetic concerns from the surgical wounds. In a follow-up phone discussion with patient 10 months after recovery, she reported that she had returned to work as a registered nurse and had been without any functional disability or discomfort.

Discussion

Originally described by Hippocrates in the 5th century as a complication of erysipelas, necrotizing fasciitis later became known as the “malignant ulcer.” It was subsequently described in the United States in 1871 as “hospital gangrene” by Confederate surgeon Joseph Jones.1-3 In 1952, the name was later modified to necrotizing fasciitis by Wilson.4

Today, necrotizing fasciitis is an uncommon disease process, yet one that must be recognized and treated immediately. If not dealt with promptly and aggressively, the virulent and toxin-producing bacteria— most commonly GAS pyogenes— will cause severe systemic toxicity and may lead to death.5

Incidences and Outcomes

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 9,000 to 11,500 cases of invasive GAS disease occur each year in the United States, resulting in approximately 1,000 to 1,800 deaths annually. Necrotizing fasciitis comprises an average of 6% to 7% (540- 805) of these invasive cases per year.6

The incidence of necrotizing fasciitis rose sharply in the mid-1980s to the early 1990s but has remained steady over the past 10 years, with 2012 CDC statistics reporting 72 cases per 32,777,740 persons through its voluntary surveillance program. This extrapolates to an estimated 686 cases of GAS-associated necrotizing fasciitis in the United States, with a reported mortality rate of 20% to 25%.7

The highest incidence of disease occurs in the elderly and in patients with diabetes, immunosuppression, and peripheral vascular disease. In children, varicella infection is a known risk factor.8

Other risk factors include obesity, alcohol use, malnutrition, and smoking, as well as corticosteroid use and chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Despite the large number of predisposing factors that have been identified, half of all cases of necrotizing fasciitis occur in healthy individuals.9-14

Etiology

Necrotizing fasciitis is thought to be caused by at least two distinct bacteriologic entities. Type I is considered polymicrobial, with Bacteriodes, Clostridium, and Peptostreptococcus, in combination with anaerobic Streptococcus (other than GAS) and Enterobacteriaceae (eg, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella), being the most common infecting species. Type II causative agents include GAS and other β-hemolytic streptococci— alone or with other species of Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin- resistant S aureus.8 In rare instances, the causative agent is fungal.

Treatment

In a review of patient medical records, Wong et al15 demonstrated that prompt recognition and surgical management of necrotizing fasciitis (ie, within 24 hours of presentation) resulted in improved outcomes. Since the particular causative agent of necrotizing fasciitis in each case is usually unknown, initial treatment should include broad-spectrum IV antibiotics— which are active against grampositive, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria—with special consideration for GAS and Clostridium (Table). It is not recommended that initial empiric therapy include antifungals. In this case, the patient was in the OR within 10 hours from presentation, was started immediately on antibiotic regimens for hospital-specific sepsis, and was given appropriate resuscitative measures.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is mentioned in the literature as an adjunct to surgery and antibiotics in the treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. Acting as a bactericidal/ bacteriostatic agent against anaerobic bacteria by increasing formation of free oxygen radicals, this therapy is thought to restore the bacterial killing capacity of leukocytes in a hypoxic wound by increasing oxygen tension. Treatment with hyperbaric oxygen may also better define necrotic tissue, facilitating more precise amputation and debridement. Although there are no randomized controlled studies in humans, several authors have shown a reduction in mortality and morbidity with the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, in conjunction with early antibiotic and surgical treatment, in animal models and in retrospective studies of patients. 19 When available, hyperbaric oxygen can be initiated once antibiotics have been started and debridement has been performed. The use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy should not delay definitive surgical debridement.

Our case demonstrates a true surgical emergency—one that was appropriately managed with a multidisciplinary team approach. A high index of suspicion by the examining ED staff and surgical consultants led to supportive measures to maintain the patient’s vital signs and ultimately her life. Despite having no clear etiology for the cause of necrotizing fasciitis, we believe it may have resulted from the patient’s prior dental work or chronic NSAID use. Although there is no causal relationship, reports suggest that NSAIDs may prevent prompt recognition and accelerate the infection by altering its initial presentation.20 The patient reported no recent use of anti-inflammatory medication in association with her pain—only for fever.

This report also underscores the importance of urgent MRI in the ED setting. In addition to helping exclude other diagnoses involving the hip joint, MRI provided a roadmap for debridement of active infection. Moreover, the test eliminated the need to explore the left hip joint as well as the risk of seeding a sterile space.21

Conclusion

- Descamps V, Aitken J, Lee MG. Hippocrates on necrotising fasciitis [letter]. Lancet. 1994; 344(8921):556.

- Jones J. Investigations upon the nature, causes, and treatments of hospital gangrene as it prevailed in the Confederate armies 1861-1865. In: Hastings HF, ed. US Sanitary Commission, Surgical memoirs of the War of Rebellion. New York, New York: Riverside; 1871:146-170.

- Loudon I. Necrotising fasciitis, hospital gangrene, and phagedena. Lancet. 1994;344(8934):1416-1419.

- Wilson B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Am Surg. 1952;18(4):416-431.

- Green RJ, Dafoe DC, Raffin TA. Necrotizing fasciitis. Chest. 1996;110(1):219-229.

- Necrotizing fasciitis: A Rare Disease, Especially for the Healthy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/Features/NecrotizingFasciitis/. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- ABCs report: group A Streptococcus, 2012-provisional. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs): Emerging Infections Program Network. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/gas12.html. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- Stevens, DL, Baddour, LM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. UpToDate Web site. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/necrotizing-soft-tissue-infections. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- Bellapianta J, Ljungquist K, Tobin E, Uhl R. Necrotizing Fasciitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(3):174-182.

- Childers BJ, Potyondy LD, Nachreiner R, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: A fourteen-year retrospective study of 163 consecutive patients. Am Surg. 2002;68(2):109-116.

- Dufel S, Martino M. Simple cellulitis or a more serious infection? J Fam Pract. 2006;55(5):396-400.

- Lamagni TL, Neal S, Keshishian C, et al. Severe Streptococcus pyogenes infections, United Kingdom, 2003-2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(2):202-209.

- Sharkawy A, Low D, Saginur R, et al. Severe group A streptococcal soft-tissue infections in Ontario: 1992-1996. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(4):454-460.

- Sudarsky LA, Laschinger JC, Coppa GF, Spencer FC. Improved results from a standardized approach in treating patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Ann Surg. 1987; 206(5):661-665.

- Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(8):1454-1460.

- Khan, AT, Tahmeedullah, Obajdullah. Treatment of necrotizing fasciitis with quinolones. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2003;13(11): 649-652.

- Schwartz, RA. Necrotizing fasciitis empiric therapy. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/

article/2012058-overview. Accessed January 2, 2014. - Stevens, DL, Bisno, AL, Chambers, HF, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1373-1406.

- Mechem, CC, Manaker, S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. UpToDate Web site. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hyperbaric-oxygen-therapy?source=search_result&search=Mechem%2C+C.+Crawford%2C++Manaker%2C+Scott.+Hyperbaric+Oxygen+Therapy.&selectedTitle=8%7E91. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- Aronoff DM, Bloch KC. Assessing the relationship between the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A streptococcus. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82(4):225-235.

- Tang WM, Wong JW, Wong LL, Leong JC. Streptococcal necrotizing myositis: the role of magnetic resonance imaging. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(11):1723-1726.

- Descamps V, Aitken J, Lee MG. Hippocrates on necrotising fasciitis [letter]. Lancet. 1994; 344(8921):556.

- Jones J. Investigations upon the nature, causes, and treatments of hospital gangrene as it prevailed in the Confederate armies 1861-1865. In: Hastings HF, ed. US Sanitary Commission, Surgical memoirs of the War of Rebellion. New York, New York: Riverside; 1871:146-170.

- Loudon I. Necrotising fasciitis, hospital gangrene, and phagedena. Lancet. 1994;344(8934):1416-1419.

- Wilson B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Am Surg. 1952;18(4):416-431.

- Green RJ, Dafoe DC, Raffin TA. Necrotizing fasciitis. Chest. 1996;110(1):219-229.

- Necrotizing fasciitis: A Rare Disease, Especially for the Healthy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/Features/NecrotizingFasciitis/. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- ABCs report: group A Streptococcus, 2012-provisional. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs): Emerging Infections Program Network. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/gas12.html. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- Stevens, DL, Baddour, LM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. UpToDate Web site. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/necrotizing-soft-tissue-infections. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- Bellapianta J, Ljungquist K, Tobin E, Uhl R. Necrotizing Fasciitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(3):174-182.

- Childers BJ, Potyondy LD, Nachreiner R, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: A fourteen-year retrospective study of 163 consecutive patients. Am Surg. 2002;68(2):109-116.

- Dufel S, Martino M. Simple cellulitis or a more serious infection? J Fam Pract. 2006;55(5):396-400.

- Lamagni TL, Neal S, Keshishian C, et al. Severe Streptococcus pyogenes infections, United Kingdom, 2003-2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(2):202-209.

- Sharkawy A, Low D, Saginur R, et al. Severe group A streptococcal soft-tissue infections in Ontario: 1992-1996. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(4):454-460.

- Sudarsky LA, Laschinger JC, Coppa GF, Spencer FC. Improved results from a standardized approach in treating patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Ann Surg. 1987; 206(5):661-665.

- Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(8):1454-1460.

- Khan, AT, Tahmeedullah, Obajdullah. Treatment of necrotizing fasciitis with quinolones. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2003;13(11): 649-652.

- Schwartz, RA. Necrotizing fasciitis empiric therapy. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/

article/2012058-overview. Accessed January 2, 2014. - Stevens, DL, Bisno, AL, Chambers, HF, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1373-1406.

- Mechem, CC, Manaker, S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. UpToDate Web site. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hyperbaric-oxygen-therapy?source=search_result&search=Mechem%2C+C.+Crawford%2C++Manaker%2C+Scott.+Hyperbaric+Oxygen+Therapy.&selectedTitle=8%7E91. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- Aronoff DM, Bloch KC. Assessing the relationship between the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A streptococcus. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82(4):225-235.

- Tang WM, Wong JW, Wong LL, Leong JC. Streptococcal necrotizing myositis: the role of magnetic resonance imaging. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(11):1723-1726.