User login

Case Report

A 45-year-old man presented with persistent swelling and “black-and-blue” lesions on the legs, feet, and toes of 6 months’ duration. The painless lesions first appeared on the left lower leg and then began to appear on the right leg in recent months. Three weeks prior to presentation, he developed swelling of the left lower leg during hospitalization for a lumbar laminectomy. A venous ultrasound was negative for a deep vein thrombosis. He denied trauma or history of bleeding diathesis. He did not report symptoms of dyspnea, angina, or claudication, and a review of systems was unremarkable.

The patient’s medical history included spinal stenosis, chronic back pain, osteoarthritis, and anxiety. His medications included oxycodone, zolpidem, and alprazolam. In addition to a recent lumbar laminectomy, he had undergone extensive dental work in the last 6 months. The patient denied the use of cigarettes, alcohol, or intravenous drugs.

Physical examination revealed scattered, purple, segmented patches on the dorsal and plantar aspects of the feet, both calves, both heels, and toes (Figure 1). Mild nonpitting edema was present below the left knee along with edema on the dorsum of the left foot. The distribution of the lesions was initially suggestive of cholesterol embolization syndrome; however, both the femoral and posterior tibial pulses were symmetric and palpable (+2). Well-demarcated violaceous plaques with central clearing and a rustlike discoloration were noted on the hard and soft palates. Cervical lymphadenopathy was not present.

|

Laboratory tests including a repeat venous ultrasound of the left lower leg revealed no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. Ankle brachial index revealed no abnormalities and blood flow to the lower legs was adequate. Computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable except for mild splenomegaly and moderate cardiomegaly. Lastly, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 1 and HIV-2 enzyme immunoassay was reactive.

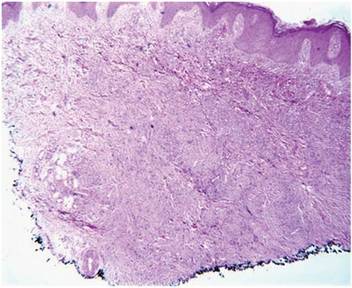

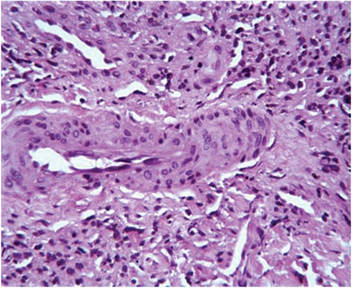

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy from the right fourth toe was representative of the plaque stage of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) with a diffuse collection of extravasated erythrocytes and neoplastic vascular proliferation among a background of numerous plasma cells and hemosiderophages (Figure 2). Higher magnification illustrated the promontory sign, whereby native vessels encroach on neoplastic slitlike vascular spaces (Figure 3). A final diagnosis of AIDS-related KS was made. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist for evaluation of his CD4 levels and HIV management.

Comment

Kaposi sarcoma is a neoplastic proliferation of the blood vessels in the skin characterized by the formation of violaceous macules and papules that often appear on a single distal extremity, such as the foot. Over time the lesions can develop on the opposite extremity and coalesce into poorly demarcated plaques and nodules with accompanying stasis and lymphedema of the involved extremities.1 Evolution of the lesions depends on the KS subtype. The most common clinical variant of KS is the classic form, which primarily is seen in those of Mediterranean, Eastern European, or Ashkenazi Jewish descent, with a predilection for men and older adults.1,2 The endemic form of KS, or African KS, is more aggressive with rapid visceral involvement and rare skin lesions; it is common among prepubertal children in sub-Saharan Africa with no predilection for either sex.2 In the setting of severe immune suppression, organ transplantation, or chemotherapy, a third KS subtype known as iatrogenic KS can occur. The clinical course of iatrogenic KS may range from scattered cutaneous lesions to diffuse involvement secondary to increased dosages and long-term use of immunosuppressive agents.2

Our patient had AIDS-related or epidemic KS. AIDS-related KS is largely predominant among homosexual men, but due to the awareness of safe sexual practices and the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), KS incidence in the United States has declined.1,2 However, despite recent advances in HIV therapy, AIDS-related KS is still the most common neoplasm seen in AIDS patients and is the presenting manifestation of AIDS in up to 30% of cases.3 Up to 22% of cases first appear on the gingiva, hard palate, and tongue, with concomitant dysphagia and airway obstruction in severe cases.4,5 More advanced cases of AIDS-related KS can present with initial symptoms such as abdominal pain, melena, dyspnea, lymphadenopathy, and weight loss, which suggests involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and other organ systems.

Regardless of the subtype, the etiology of KS currently is thought to be secondary to infection with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), also known as Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV).1 Human immunodeficiency virus infection can enhance KSHV expression through the HIV transactivator protein, which activates KSHV oncogenes and angiogenic growth factors to promote the development of KS lesions.2,6Likewise, KSHV enhances HIV upregulation through latency-associated nuclear antigen, a protein that interacts with HIV Tat protein to further activate long terminal repeats of HIV-1.2

The differential diagnosis of KS is broad. The slightly elevated, pinkish reddish discolorations of KS may resemble verruca plana and/or squamous cell carcinoma on visual observation, whereas nodular KS may resemble giant cell granuloma, pyogenic granuloma, or hemangiopericytoma.4,7 Cases of KS with lymph node involvement may include a differential diagnosis of lymphoma, angiosarcoma, and bacillary angiomatosis.7 Other vascular pathologies that may be considered in the differential diagnosis include vascular tumors (eg, spindle cell hemangioma), fibrohistiocytic tumors (eg, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans), and a collection of spindle cell mesenchymal tumors.8

Kaposi sarcoma progresses through several histologic stages beginning with the patch stage, then progressing to the plaque stage, and finally culminating in the nodular stage. The patch stage is the first stage in KS progression and a crowded dermis can be seen with the formation of slitlike vascular spaces lined by endothelial cells with red blood cell extravasation into the lumens of newly formed vascular channels, hence demonstrating the promontory sign.8 In the plaque stage, the promontory sign still is present and there is a greater presence of slitlike spaces, giving the micrograph an overall sievelike appearance. Erythrocytes can be found residing within the clear cytoplasm of spindled endothelial cells, leading to the development of autolumination. Finally, the nodular stage is characterized by a neoplastic proliferation of monomorphic spindle cells that form fasciclelike nests in the dermis.8 To distinguish KS from other angioproliferative tumors, one can stain for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, which is found in the nuclei of infected endothelial cells.1,8,9

Kaposi sarcoma is treated through a variety of mechanisms depending on the subtype. Classic KS lesions often can be observed as they a follow a benign and nonaggressive course.1 Highly active antiretroviral therapy is the mainstay of care in AIDS-related KS and has led to regression of lesions and a remarkable decline in the incidence of KS.3 The HAART regimen consists of a protease inhibitor or nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor with the addition of 2 nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors. More advanced or refractory cases of KS often require dual treatment with HAART and a chemotherapy agent such as pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Combination therapy has been shown to result in stronger therapeutic responses and lower relapse rates in contrast to HAART alone.7 Patients also may consider other treatment modalities to manage KS lesions such as surgical removal of lesions, laser therapy, paclitaxel, interferon alfa, oral etoposide, thalidomide, and topical therapies such as imiquimod cream 5% and alitretinoin.1,7

Conclusion

Kaposi sarcoma is a rare but concerning dermatologic condition that signals the need for further diagnostic evaluation. Coexpression of viruses such as HIV and HHV-8 can result in a more virulent and rapid progression of KS to encompass both mucous membrane and systemic involvement. Our patient’s lesions were the first presenting sign of HIV infection despite being asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, which is alarming in the sense that more than 21% of HIV-infected individuals in the United States have not been clinically diagnosed.10 Inquiry of HIV risk factors and routine screening for HIV should be performed in refractory cases of skin disease as an underlying clue to further investigate the immune system. We present our unique case of mucocutaneous development of KS in an asymptomatic HIV-positive man to stress the importance of KS recognition and management.

1. Jan MM, Laskas JW, Griffin TD. Eruptive Kaposi sarcoma: an unusual presentation in an HIV-negative patient. Cutis. 2011;87:34-38.

2. Geraminejad P, Memar O, Aronson I, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and other manifestations of human herpesvirus 8. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:641-655.

3. Kharkar V, Gutte RM, Khopkar U, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma: a presenting manifestation of HIV infection in an Indian. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:391-393.

4. Naidu A, Havard DB, Ray JM, et al. Oral and maxillofacial pathology case of the month. Kaposi’s sarcoma. Tex Dent J. 2011;128:376-377, 382-383.

5. Lawson G, Matar N, Kesch S, et al. Laryngeal Kaposi sarcoma: case report and literature review. B-ENT. 2010;6:285-288.

6. Sullivan RJ, Pantanowitz L, Casper C, et al. HIV/AIDS: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus disease: Kaposi sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1209-1215.

7. Uldrick TS, Whitby D. Update on KSHV epidemiology, Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma [published online ahead of print March 4, 2011]. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:150-162.

8. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

9. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

10. Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Hall HI, et al. Proportions of Kaposi sarcoma, selected non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and cervical cancer in the United States occurring in persons with AIDS, 1980-2007 [published correction appears in JAMA. 2011;306:1548]. JAMA. 2011;305:1450-1459.

Case Report

A 45-year-old man presented with persistent swelling and “black-and-blue” lesions on the legs, feet, and toes of 6 months’ duration. The painless lesions first appeared on the left lower leg and then began to appear on the right leg in recent months. Three weeks prior to presentation, he developed swelling of the left lower leg during hospitalization for a lumbar laminectomy. A venous ultrasound was negative for a deep vein thrombosis. He denied trauma or history of bleeding diathesis. He did not report symptoms of dyspnea, angina, or claudication, and a review of systems was unremarkable.

The patient’s medical history included spinal stenosis, chronic back pain, osteoarthritis, and anxiety. His medications included oxycodone, zolpidem, and alprazolam. In addition to a recent lumbar laminectomy, he had undergone extensive dental work in the last 6 months. The patient denied the use of cigarettes, alcohol, or intravenous drugs.

Physical examination revealed scattered, purple, segmented patches on the dorsal and plantar aspects of the feet, both calves, both heels, and toes (Figure 1). Mild nonpitting edema was present below the left knee along with edema on the dorsum of the left foot. The distribution of the lesions was initially suggestive of cholesterol embolization syndrome; however, both the femoral and posterior tibial pulses were symmetric and palpable (+2). Well-demarcated violaceous plaques with central clearing and a rustlike discoloration were noted on the hard and soft palates. Cervical lymphadenopathy was not present.

|

Laboratory tests including a repeat venous ultrasound of the left lower leg revealed no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. Ankle brachial index revealed no abnormalities and blood flow to the lower legs was adequate. Computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable except for mild splenomegaly and moderate cardiomegaly. Lastly, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 1 and HIV-2 enzyme immunoassay was reactive.

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy from the right fourth toe was representative of the plaque stage of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) with a diffuse collection of extravasated erythrocytes and neoplastic vascular proliferation among a background of numerous plasma cells and hemosiderophages (Figure 2). Higher magnification illustrated the promontory sign, whereby native vessels encroach on neoplastic slitlike vascular spaces (Figure 3). A final diagnosis of AIDS-related KS was made. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist for evaluation of his CD4 levels and HIV management.

Comment

Kaposi sarcoma is a neoplastic proliferation of the blood vessels in the skin characterized by the formation of violaceous macules and papules that often appear on a single distal extremity, such as the foot. Over time the lesions can develop on the opposite extremity and coalesce into poorly demarcated plaques and nodules with accompanying stasis and lymphedema of the involved extremities.1 Evolution of the lesions depends on the KS subtype. The most common clinical variant of KS is the classic form, which primarily is seen in those of Mediterranean, Eastern European, or Ashkenazi Jewish descent, with a predilection for men and older adults.1,2 The endemic form of KS, or African KS, is more aggressive with rapid visceral involvement and rare skin lesions; it is common among prepubertal children in sub-Saharan Africa with no predilection for either sex.2 In the setting of severe immune suppression, organ transplantation, or chemotherapy, a third KS subtype known as iatrogenic KS can occur. The clinical course of iatrogenic KS may range from scattered cutaneous lesions to diffuse involvement secondary to increased dosages and long-term use of immunosuppressive agents.2

Our patient had AIDS-related or epidemic KS. AIDS-related KS is largely predominant among homosexual men, but due to the awareness of safe sexual practices and the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), KS incidence in the United States has declined.1,2 However, despite recent advances in HIV therapy, AIDS-related KS is still the most common neoplasm seen in AIDS patients and is the presenting manifestation of AIDS in up to 30% of cases.3 Up to 22% of cases first appear on the gingiva, hard palate, and tongue, with concomitant dysphagia and airway obstruction in severe cases.4,5 More advanced cases of AIDS-related KS can present with initial symptoms such as abdominal pain, melena, dyspnea, lymphadenopathy, and weight loss, which suggests involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and other organ systems.

Regardless of the subtype, the etiology of KS currently is thought to be secondary to infection with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), also known as Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV).1 Human immunodeficiency virus infection can enhance KSHV expression through the HIV transactivator protein, which activates KSHV oncogenes and angiogenic growth factors to promote the development of KS lesions.2,6Likewise, KSHV enhances HIV upregulation through latency-associated nuclear antigen, a protein that interacts with HIV Tat protein to further activate long terminal repeats of HIV-1.2

The differential diagnosis of KS is broad. The slightly elevated, pinkish reddish discolorations of KS may resemble verruca plana and/or squamous cell carcinoma on visual observation, whereas nodular KS may resemble giant cell granuloma, pyogenic granuloma, or hemangiopericytoma.4,7 Cases of KS with lymph node involvement may include a differential diagnosis of lymphoma, angiosarcoma, and bacillary angiomatosis.7 Other vascular pathologies that may be considered in the differential diagnosis include vascular tumors (eg, spindle cell hemangioma), fibrohistiocytic tumors (eg, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans), and a collection of spindle cell mesenchymal tumors.8

Kaposi sarcoma progresses through several histologic stages beginning with the patch stage, then progressing to the plaque stage, and finally culminating in the nodular stage. The patch stage is the first stage in KS progression and a crowded dermis can be seen with the formation of slitlike vascular spaces lined by endothelial cells with red blood cell extravasation into the lumens of newly formed vascular channels, hence demonstrating the promontory sign.8 In the plaque stage, the promontory sign still is present and there is a greater presence of slitlike spaces, giving the micrograph an overall sievelike appearance. Erythrocytes can be found residing within the clear cytoplasm of spindled endothelial cells, leading to the development of autolumination. Finally, the nodular stage is characterized by a neoplastic proliferation of monomorphic spindle cells that form fasciclelike nests in the dermis.8 To distinguish KS from other angioproliferative tumors, one can stain for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, which is found in the nuclei of infected endothelial cells.1,8,9

Kaposi sarcoma is treated through a variety of mechanisms depending on the subtype. Classic KS lesions often can be observed as they a follow a benign and nonaggressive course.1 Highly active antiretroviral therapy is the mainstay of care in AIDS-related KS and has led to regression of lesions and a remarkable decline in the incidence of KS.3 The HAART regimen consists of a protease inhibitor or nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor with the addition of 2 nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors. More advanced or refractory cases of KS often require dual treatment with HAART and a chemotherapy agent such as pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Combination therapy has been shown to result in stronger therapeutic responses and lower relapse rates in contrast to HAART alone.7 Patients also may consider other treatment modalities to manage KS lesions such as surgical removal of lesions, laser therapy, paclitaxel, interferon alfa, oral etoposide, thalidomide, and topical therapies such as imiquimod cream 5% and alitretinoin.1,7

Conclusion

Kaposi sarcoma is a rare but concerning dermatologic condition that signals the need for further diagnostic evaluation. Coexpression of viruses such as HIV and HHV-8 can result in a more virulent and rapid progression of KS to encompass both mucous membrane and systemic involvement. Our patient’s lesions were the first presenting sign of HIV infection despite being asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, which is alarming in the sense that more than 21% of HIV-infected individuals in the United States have not been clinically diagnosed.10 Inquiry of HIV risk factors and routine screening for HIV should be performed in refractory cases of skin disease as an underlying clue to further investigate the immune system. We present our unique case of mucocutaneous development of KS in an asymptomatic HIV-positive man to stress the importance of KS recognition and management.

Case Report

A 45-year-old man presented with persistent swelling and “black-and-blue” lesions on the legs, feet, and toes of 6 months’ duration. The painless lesions first appeared on the left lower leg and then began to appear on the right leg in recent months. Three weeks prior to presentation, he developed swelling of the left lower leg during hospitalization for a lumbar laminectomy. A venous ultrasound was negative for a deep vein thrombosis. He denied trauma or history of bleeding diathesis. He did not report symptoms of dyspnea, angina, or claudication, and a review of systems was unremarkable.

The patient’s medical history included spinal stenosis, chronic back pain, osteoarthritis, and anxiety. His medications included oxycodone, zolpidem, and alprazolam. In addition to a recent lumbar laminectomy, he had undergone extensive dental work in the last 6 months. The patient denied the use of cigarettes, alcohol, or intravenous drugs.

Physical examination revealed scattered, purple, segmented patches on the dorsal and plantar aspects of the feet, both calves, both heels, and toes (Figure 1). Mild nonpitting edema was present below the left knee along with edema on the dorsum of the left foot. The distribution of the lesions was initially suggestive of cholesterol embolization syndrome; however, both the femoral and posterior tibial pulses were symmetric and palpable (+2). Well-demarcated violaceous plaques with central clearing and a rustlike discoloration were noted on the hard and soft palates. Cervical lymphadenopathy was not present.

|

Laboratory tests including a repeat venous ultrasound of the left lower leg revealed no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. Ankle brachial index revealed no abnormalities and blood flow to the lower legs was adequate. Computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable except for mild splenomegaly and moderate cardiomegaly. Lastly, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 1 and HIV-2 enzyme immunoassay was reactive.

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy from the right fourth toe was representative of the plaque stage of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) with a diffuse collection of extravasated erythrocytes and neoplastic vascular proliferation among a background of numerous plasma cells and hemosiderophages (Figure 2). Higher magnification illustrated the promontory sign, whereby native vessels encroach on neoplastic slitlike vascular spaces (Figure 3). A final diagnosis of AIDS-related KS was made. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist for evaluation of his CD4 levels and HIV management.

Comment

Kaposi sarcoma is a neoplastic proliferation of the blood vessels in the skin characterized by the formation of violaceous macules and papules that often appear on a single distal extremity, such as the foot. Over time the lesions can develop on the opposite extremity and coalesce into poorly demarcated plaques and nodules with accompanying stasis and lymphedema of the involved extremities.1 Evolution of the lesions depends on the KS subtype. The most common clinical variant of KS is the classic form, which primarily is seen in those of Mediterranean, Eastern European, or Ashkenazi Jewish descent, with a predilection for men and older adults.1,2 The endemic form of KS, or African KS, is more aggressive with rapid visceral involvement and rare skin lesions; it is common among prepubertal children in sub-Saharan Africa with no predilection for either sex.2 In the setting of severe immune suppression, organ transplantation, or chemotherapy, a third KS subtype known as iatrogenic KS can occur. The clinical course of iatrogenic KS may range from scattered cutaneous lesions to diffuse involvement secondary to increased dosages and long-term use of immunosuppressive agents.2

Our patient had AIDS-related or epidemic KS. AIDS-related KS is largely predominant among homosexual men, but due to the awareness of safe sexual practices and the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), KS incidence in the United States has declined.1,2 However, despite recent advances in HIV therapy, AIDS-related KS is still the most common neoplasm seen in AIDS patients and is the presenting manifestation of AIDS in up to 30% of cases.3 Up to 22% of cases first appear on the gingiva, hard palate, and tongue, with concomitant dysphagia and airway obstruction in severe cases.4,5 More advanced cases of AIDS-related KS can present with initial symptoms such as abdominal pain, melena, dyspnea, lymphadenopathy, and weight loss, which suggests involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and other organ systems.

Regardless of the subtype, the etiology of KS currently is thought to be secondary to infection with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), also known as Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV).1 Human immunodeficiency virus infection can enhance KSHV expression through the HIV transactivator protein, which activates KSHV oncogenes and angiogenic growth factors to promote the development of KS lesions.2,6Likewise, KSHV enhances HIV upregulation through latency-associated nuclear antigen, a protein that interacts with HIV Tat protein to further activate long terminal repeats of HIV-1.2

The differential diagnosis of KS is broad. The slightly elevated, pinkish reddish discolorations of KS may resemble verruca plana and/or squamous cell carcinoma on visual observation, whereas nodular KS may resemble giant cell granuloma, pyogenic granuloma, or hemangiopericytoma.4,7 Cases of KS with lymph node involvement may include a differential diagnosis of lymphoma, angiosarcoma, and bacillary angiomatosis.7 Other vascular pathologies that may be considered in the differential diagnosis include vascular tumors (eg, spindle cell hemangioma), fibrohistiocytic tumors (eg, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans), and a collection of spindle cell mesenchymal tumors.8

Kaposi sarcoma progresses through several histologic stages beginning with the patch stage, then progressing to the plaque stage, and finally culminating in the nodular stage. The patch stage is the first stage in KS progression and a crowded dermis can be seen with the formation of slitlike vascular spaces lined by endothelial cells with red blood cell extravasation into the lumens of newly formed vascular channels, hence demonstrating the promontory sign.8 In the plaque stage, the promontory sign still is present and there is a greater presence of slitlike spaces, giving the micrograph an overall sievelike appearance. Erythrocytes can be found residing within the clear cytoplasm of spindled endothelial cells, leading to the development of autolumination. Finally, the nodular stage is characterized by a neoplastic proliferation of monomorphic spindle cells that form fasciclelike nests in the dermis.8 To distinguish KS from other angioproliferative tumors, one can stain for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, which is found in the nuclei of infected endothelial cells.1,8,9

Kaposi sarcoma is treated through a variety of mechanisms depending on the subtype. Classic KS lesions often can be observed as they a follow a benign and nonaggressive course.1 Highly active antiretroviral therapy is the mainstay of care in AIDS-related KS and has led to regression of lesions and a remarkable decline in the incidence of KS.3 The HAART regimen consists of a protease inhibitor or nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor with the addition of 2 nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors. More advanced or refractory cases of KS often require dual treatment with HAART and a chemotherapy agent such as pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Combination therapy has been shown to result in stronger therapeutic responses and lower relapse rates in contrast to HAART alone.7 Patients also may consider other treatment modalities to manage KS lesions such as surgical removal of lesions, laser therapy, paclitaxel, interferon alfa, oral etoposide, thalidomide, and topical therapies such as imiquimod cream 5% and alitretinoin.1,7

Conclusion

Kaposi sarcoma is a rare but concerning dermatologic condition that signals the need for further diagnostic evaluation. Coexpression of viruses such as HIV and HHV-8 can result in a more virulent and rapid progression of KS to encompass both mucous membrane and systemic involvement. Our patient’s lesions were the first presenting sign of HIV infection despite being asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, which is alarming in the sense that more than 21% of HIV-infected individuals in the United States have not been clinically diagnosed.10 Inquiry of HIV risk factors and routine screening for HIV should be performed in refractory cases of skin disease as an underlying clue to further investigate the immune system. We present our unique case of mucocutaneous development of KS in an asymptomatic HIV-positive man to stress the importance of KS recognition and management.

1. Jan MM, Laskas JW, Griffin TD. Eruptive Kaposi sarcoma: an unusual presentation in an HIV-negative patient. Cutis. 2011;87:34-38.

2. Geraminejad P, Memar O, Aronson I, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and other manifestations of human herpesvirus 8. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:641-655.

3. Kharkar V, Gutte RM, Khopkar U, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma: a presenting manifestation of HIV infection in an Indian. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:391-393.

4. Naidu A, Havard DB, Ray JM, et al. Oral and maxillofacial pathology case of the month. Kaposi’s sarcoma. Tex Dent J. 2011;128:376-377, 382-383.

5. Lawson G, Matar N, Kesch S, et al. Laryngeal Kaposi sarcoma: case report and literature review. B-ENT. 2010;6:285-288.

6. Sullivan RJ, Pantanowitz L, Casper C, et al. HIV/AIDS: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus disease: Kaposi sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1209-1215.

7. Uldrick TS, Whitby D. Update on KSHV epidemiology, Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma [published online ahead of print March 4, 2011]. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:150-162.

8. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

9. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

10. Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Hall HI, et al. Proportions of Kaposi sarcoma, selected non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and cervical cancer in the United States occurring in persons with AIDS, 1980-2007 [published correction appears in JAMA. 2011;306:1548]. JAMA. 2011;305:1450-1459.

1. Jan MM, Laskas JW, Griffin TD. Eruptive Kaposi sarcoma: an unusual presentation in an HIV-negative patient. Cutis. 2011;87:34-38.

2. Geraminejad P, Memar O, Aronson I, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and other manifestations of human herpesvirus 8. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:641-655.

3. Kharkar V, Gutte RM, Khopkar U, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma: a presenting manifestation of HIV infection in an Indian. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:391-393.

4. Naidu A, Havard DB, Ray JM, et al. Oral and maxillofacial pathology case of the month. Kaposi’s sarcoma. Tex Dent J. 2011;128:376-377, 382-383.

5. Lawson G, Matar N, Kesch S, et al. Laryngeal Kaposi sarcoma: case report and literature review. B-ENT. 2010;6:285-288.

6. Sullivan RJ, Pantanowitz L, Casper C, et al. HIV/AIDS: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus disease: Kaposi sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1209-1215.

7. Uldrick TS, Whitby D. Update on KSHV epidemiology, Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma [published online ahead of print March 4, 2011]. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:150-162.

8. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

9. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

10. Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Hall HI, et al. Proportions of Kaposi sarcoma, selected non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and cervical cancer in the United States occurring in persons with AIDS, 1980-2007 [published correction appears in JAMA. 2011;306:1548]. JAMA. 2011;305:1450-1459.

Practice Points

- Kaposi sarcoma is a rare malignant proliferation of endothelial cells with many subtypes.

- Kaposi sarcoma in patients with coexpression of human immunodeficiency virus and human herpesvirus 8 often have a more virulent and rapid progression of disease.