User login

Psychiatrists are suddenly viewed as experts in treating menopause-related mood problems because of our expertise with using psychotropics. Practically overnight, the Women’s Health Initiative studies1,2 have made women and their doctors think twice about using estrogen. Instead, many are turning to psychiatric medications that have been shown to improve both mood and hot flashes—without estrogen’s potential risks.

Chances are good that after an Ob/Gyn has tried one or two psychotropics without success or with too many side effects, he or she will ask a psychiatrist to consult for certain patients. How well-prepared are you to assume this role?

If your recall of female reproductive physiology from medical school is incomplete, read on about one approach to a perimenopausal patient with depressed mood. This review can help you:

- discuss menopause knowledgeably when other physicians refer their patients to you

- provide effective, up-to-date treatments for menopause-related mood and sexual problems, using psychotropics or hormones, alone or in combination.

Irritable, with no interest in sex

Anne, age 51, has been referred to you for complaints of depressed mood and low libido. She says she has become irritable and snaps easily at her two children and her husband. She has no interest in sex, no urge to masturbate, and has had no sexual intercourse for 6 months.

Table 1

Why mood problems may occur during menopause

| Hypothesis | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Psychodynamic | Onset of menopause is a critical life event and a readjustment of self-concept |

| Sociologic | Mood changes are caused by changing life circumstances at menopause (‘empty nest,’ aging parents, health changes) |

| Domino | Depressed mood is caused by hot flashes due to declining estrogen levels, which cause chronic sleep deprivation with subsequent irritability and memory and mood changes |

| Biochemical | Decreasing estrogen leads to neurochemical changes in the brain (serotonin, dopamine, cholinergic, GABA, norepinephrine) |

Anne also complains of fatigue, dry hair and skin, warm flushes, and painful joints. She has no personal or family history of depression. She is not suicidal but states that she really doesn’t want to live anymore if “this is it.”

HOT FLASHES: A SPARK FOR DEPRESSION

Women who experience their first depression after age 50 do not fit the usual DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for depression. The Massachusetts Women’s Health Study3 found that 52% of women who experience depressed mood in the perimenopause have never had a depression before. This study also found a correlation between a longer perimenopause (>27 months) and increased risk of depressed mood. At the same time, women who have had a prior depression are 4 to 9 times more likely to experience depressive symptoms during perimenopause than those who have never had a depression before.4

The increased mood symptoms may be related to psychodynamic, sociologic, or biochemical factors, or they may result from a domino effect triggered by declining estrogen levels (Table 1). Women who experience vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes are at 4.6 times greater risk for depression than those who are hot flash-free.5

Hot flashes begin on average at age 51, which is also the average age when natural menopause begins. During menopause, most women (82%) experience hot flashes (suddenly feeling hot and sweating during the day), warm flushes (a sensation of warmth or heat spreading over the skin), and night sweats (Table 2). All women who undergo surgical menopause experience hot flashes.

Hot flashes are moderate to severe for 40% of women who experience them and persist for 5 to 15 years. By definition, moderate to severe hot flashes occur 6 to 10 or more times daily, last 6 to 10 minutes each, and are often preceded by anxiety, palpitations, irritability, nervousness, or panic.

A marriage under stress

Anne says that her husband is angry about the lack of sexual intercourse, and she feels the stress in their marriage. She also is worrying about her children leaving for college and about her mother’s ill health.

She scores 20 on the Beck Depression Inventory, which indicates that she has mild to moderate depression. Her menstrual periods remain regular, but her cycle has shortened from 29 to 24 days. She reports experiencing some hot flashes that wake her at night and says she hasn’t had a good night’s sleep in months.

Laboratory tests show FSH of 25 mIU/mL and inhibin B <45 pg/mL. Her estradiol is 80 pg/mL, which is not yet in the menopausal range of 10 to 20 pg/mL. Her thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) is normal. Her endocrinologic and reproductive diagnosis is perimenopause.

Table 2

Symptoms of menopause related to decreased estrogen

| Brain | Irritability, mood swings, depressed mood, forgetfulness, low sex interest, sleep problems, decreased well-being |

| Body | Hot flashes, vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, fatigue, joint pain, pain with orgasm, bladder dysfunction |

TREATING HOT FLASHES IMPROVES MOOD

Until July 2002, estrogen was standard treatment for controlling hot flashes in patients such as Anne. Then the Women’s Health Initiative trial reported that estrogen’s health risks—heart attack, stroke, breast cancer, and blood clots—exceeded potential benefits during 5 years of therapy. As a result, fewer women want to take estrogen,6 and many Ob/Gyns are advising patients to get through menopause without hormones if they can.

For mild hot flashes—one to three per day—patients may only need vitamin E, 800 mg/d, and deep relaxation breathing to “rev down” the sympathetic nervous system when a hot flash occurs.

For moderate to severe hot flashes—four to 10 or more per day—estrogen replacement is the most effective therapy. Estradiol, 1 mg/d, reduces hot flashes by approximately 80 to 90%.7 Many small studies have shown that patients’ mood often improves as estrogen reduces their hot flashes.8 The recent Women’s Health Initiative Quality-of-Life study, however, reported that estrogen plus progestin did not improve mood in women ages 50 to 54 with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms, even though hot flashes were reduced and sleep may have improved.9

New drugs of choice. Because of estrogen’s effectiveness in controlling hot flashes, some women and their doctors may choose to use it briefly (18 to 24 months). For others, psychotropics are becoming the drugs of choice for mood disorders with moderate to severe hot flashes.

The serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, 75 or 150 mg/d, has been shown to reduce hot flashes by 60 to 70%.10 A new trial is investigating whether duloxetine—an SNRI awaiting FDA approval—also reduces hot flashes. Other useful agents that have been shown to reduce hot flashes by 50% or more include:

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) paroxetine CR, 12.5 mg/d to 25 mg/d,11 citalopram, 20 to 60 mg/d,12 and fluoxetine, 20 mg/d13

- gabapentin, 900 mg/d.14

For hot flashes and moderate to major depression, try an SNRI or SSRI first (see Algorithm), but consider the possible effects on sexual function. All SNRIs and SSRIs have sexual side effects, including anorgasmia and loss of libido in women and men. Among the psychotropics that improve hot flashes and mood, gabapentin is the only one that does not interfere with sexual function.

Mood improves, but still no libido

You and Ann decide on a trial of the SNRI venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, to treat her hot flashes and depressed mood. Four weeks later, her hot flashes are reduced by 50% in frequency and her mood has improved (Beck Depression Inventory score is now 10). She is feeling much better and wishes to continue taking the antidepressant.

She and her husband attempted intercourse once during the past month, although she wasn’t very interested. She did not achieve orgasm, despite adequate vaginal lubrication, and she did not enjoy the experience. “I still have no libido—zero, or even less,” she says.

TREATING LOW INTEREST IN SEX

Being angry with one’s partner is the number-one reason for decreased sexual desire in all studies. Therefore, consider couples therapy for any woman complaining of loss of interest in sex. In addition, eliminate—if possible—any medications she may be taking that have known sexual side effects, such as SSRIs or beta blockers.

If the patient complains of slow or no arousal, vaginal estrogen and/or sildenafil, 25 to 50 mg 1 hour before intercourse, may be beneficial.15 Other agents the FDA is reviewing for erectile dysfunction—such as tadalafil and vardenafil—may also help arousal problems in women.

Understanding how hormones affect female sexual desire also may help you decide what advice to give Anne and how you and her Ob/Gyn coordinate her care. For example, you might treat her sexual complaints and relationship problems while the Ob/Gyn manages symptoms of the vagina, uterus, and breast.

HOW TESTOSTERONE AFFECTS SEXUAL DESIRE

Testosterone is the hormone of sexual desire in men and women. Other female androgens include androstenedione, androstenediol, 5 α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT), dihydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and its sulfate (DHEA-S). Premenopausal women produce these androgens in the ovaries (25%), adrenal glands (25%), and peripheral tissues (50%).

Average daily serum testosterone concentrations decline in women between ages 20 and 50. Lower levels are also seen with estrogen replacement therapy or oral contraceptives, lactation, anorexia nervosa, and conditions that reduce ovarian function. Women who undergo total hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy experience a sudden 50% loss of testosterone and an 80% decline in estradiol.16

Regularly menstruating women in their 40s and early 50s can have very low testosterone levels—at least 50% lower in the first 5 to 7 days of their cycles—than they had when they were in their 30s.17 The percentage of women reporting low libido increases with age until menopause, from 30% at age 30 to about 50% at age 50. Then the rate declines to 27% in women age 50 to 59.18 After natural menopause, luteinizing hormone (LH) continues to stimulate the ovarian hilar cells and interstitial cells to produce androgens, which is why many women at age 50 have adequate testosterone levels to sustain sexual desire.

Oral estrogen replacement therapy reduces bioavailable testosterone by 42% on average, which can induce androgen deficiency in a menopausal woman.19 The increased estrogen inhibits pituitary LH and decreases stimulation of the androgen-producing cells in the ovary.20

Female androgen deficiency. A number of papers have been published on female androgen deficiency syndrome (FADS).21 Its diagnosis requires symptoms of thinning pubic and axillary hair, decreased body odor, lethargy, low mood, diminished well-being, and declining libido and orgasm, despite adequate estrogen but low levels of testosterone and DHEA.

TREATING TESTOSTERONE DEFICIENCY

Benefits of replacement therapy. Replacing testosterone in women with FADS can improve mood, well-being, motivation, cognition, sexual function related to libido, orgasm, sexual fantasies, desire to masturbate, and nipple and clitoral sensitivity.22 Muscle and bone stimulation and decreased hot flashes are also reported.23 Women with androgen deficiency symptoms and low testosterone at menopause should at least be considered for physiologic testosterone replacement.

Risks of replacement therapy. Androgen replacement therapy does carry some risks, which need to be discussed with the patient. Testosterone may lower levels of beneficial HDL cholesterol, so get the cardiologist’s clearance before you give testosterone to a woman with heart disease or an HDL cholesterol level <45 mg/dL.

Algorithm Managing mood and libido problems during perimenopause

A meta-analysis of eight clinical trials found no changes in liver function in menopausal women taking 1.25 to 2.5 mg/d of methyl testosterone. Liver toxicity has been reported in men using 10-fold higher testosterone dosages.24

At the normal level of testosterone, darkening and thickening of facial hair are rare in light-skinned, light-haired women but can occur in dark-skinned, dark-haired women. Increased irritability, excess energy, argumentativeness, and aggressive behavior have been noted if testosterone levels exceed the physiologic range.

Controlled, randomized studies are needed to assess the effects of long-term use (more than 24 months) of testosterone replacement in women.

Challenges in measuring testosterone levels. Serum free testosterone is the most reliable indicator of a woman’s androgen status, but accurately measuring testosterone levels is tricky:

- Only 2% of circulating testosterone is unbound and biologically active; the rest is bound to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) or albumin.

- In ovulating women, serum testosterone levels are higher in the morning than later in the day and vary greatly within the menstrual cycle.

- Levels of androgens and estrogen are highest during the middle one-third of the cycle—on days 10 to 16, counting the first day of menstrual bleeding as day 1.25

- Oral contraceptives also decrease androgen production by the ovary and can result in low libido in some women.26

Tests developed to measure testosterone levels in men are not sensitive enough to accurately measure women’s naturally lower serum concentrations, let alone the even lower levels characteristic of female androgen or testosterone deficiency. New measurements and standardization of normal reference ranges have been developed for women complaining of low libido.27

Tests for androgen deficiency include total testosterone, free testosterone, DHEA, and DHEAS. Measuring SHBG will help you determine the free, biologically active testosterone level and calculate the Free Androgen Index (FAI) for women (Table 3).28

Table 3

Free androgen index (FAI) values in women, by age

| Replacing a woman’s bioactive testosterone to the normal free androgen index range for her age may improve low libido. | |

| How to calculate FAI | |

| Total testosterone in nmol/L (total testosterone in ng/ml X 0.0347 X 100), divided by sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in nmol/L. | |

| Age | Normal range |

| 20 to 29 | 3.72 to 4.96 |

| 30 to 39 | 2.04 to 2.96 |

| 40 to 49 | 1.98 to 2.94 |

| 50 to 59+ | 1.78 to 2.86 |

| Source: Guay et al, reference 28. | |

A candidate for testosterone therapy?

Now that Anne’s mood, sleep, and hot flashes have improved with venlafaxine, she wants help with her lack of sexual interest. You measure her testosterone and SHBG levels and find that her free androgen index is very low at 0.51 (normal range, 1.78 to 2.86).

In collaboration with her Ob/Gyn, you and Anne decide to start her on testosterone replacement therapy. You prescribe Androgel, starting at 1/7th of a 2.5-mg foil packet (0.35 mg/d of testosterone), and instruct her to rate her sexual energy daily, using a Sexual Energy Scale.

TESTOSTERONE CHOICES FOR WOMEN

Replacing a woman’s bioactive testosterone level to the normal free androgen index range for her age group may improve low libido. Some low-dose testosterone replacement options include:

- methyl testosterone sublingual pills, 0.5 mg/d, made by a compounding pharmacy or reduced dosages of oral pills made for men. If you prescribe methyl testosterone, routine lab tests will not accurately measure serum testosterone levels—unless you order the very expensive test that is specific for methyl testosterone.

- 2% vaginal cream, applied topically to increase clitoral and genital sensitivity. It may increase blood levels moderately through absorption

- Androgel, a topical testosterone approved for men. As in Anne’s case, start with 0.35 mg/d or one-seventh of the 2.5 mg packet (ask the pharmacist to place this amount in a syringe). Instruct the patient to apply the gel to hairless skin, such as inside the forearm. Effects last about 24 hours, and you can measure serum levels accurately after 14 days. Vaginal throbbing—a normal response—may occur within 30 minutes of testosterone application.

The FDA is considering other testosterone preparations—including a testosterone patch for women and a gel in female-sized doses.

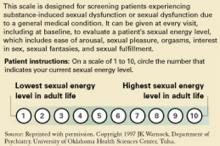

Using the Sexual Energy Scale. To monitor for a therapeutic response, ask the patient to use the Sexual Energy Scale (Figure 1).29,30 Instruct her to define her “10” as the time in life when she had the most fulfilling sexual life, was the most easily aroused, had the most sexual pleasure, and the best orgasms. Her “1” would be when she felt the worst sexually and had the least desire.

Giving supplemental estrogen. If you prescribe estrogen plus testosterone (Estratest), start with Estratest HS, which contains 0.625 mg esterified estrogens and 1.25 mg of methyl testosterone. Add a progestin if the patient is postmenopausal and has not had a hysterectomy, to protect the uterus from endometrial hyperplasia.

Women with vaginal dryness also need supplemental estrogen, which can be applied vaginally (such as Premarin cream or Estrace cream). A vaginal lubricant is not sufficient to avoid age-related vaginal atrophy, which may make intercourse difficult or impossible.

Figure 1 How to use the Sexual Energy Scale to monitor response to therapy

Libido improves modestly

Ann returns in 4 weeks with gradually improving sex drive (Sexual Energy Score is now 5). She had sexual intercourse twice in the past month and didn’t “dread” it, but also did not enjoy it or reach orgasm. You have told her that venlafaxine may slow or prevent orgasm, but she wants to keep taking it. She reports that her marital relationship is improving.

You order repeat testosterone and SHBG blood levels and find her free androgen index has improved to 1.10, which is still low. You increase the Androgel dosage to 1/5th of a 2.5 mg packet (0.5 mg/day) and continue to monitor Anne’s Sexual Energy Scale ratings at monthly follow-up visits. She has set a Sexual Energy Scale rating of 7 to 8 as her target. Anne says she appreciates your help with—as she puts it—“this embarrassing problem.”

Louann Brizendine, MD

Medicine’s understanding of menopause’s physiologic and psychological consequences is changing, just as the “baby-boom” generation is navigating this passage called the change of life. Many midlife women are unaware that the menopause transition does not begin around age 50 but spans 30 years—from ages 35 to 65. Natural menopause begins 15 years before and ends 15 years after menstruation ceases—as the brain and tissues adjust to first fluctuating then decreased estrogen levels. It occurs in three phases—early menopause, perimenopause, and late menopause—that reflect a progression of hormone changes.

EARLY MENOPAUSE: OVULATION ACCELERATES

At approximately age 35, the ovaries start producing lower levels of inhibin—a glycoprotein that inhibits pituitary production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (Figure 2). Less inhibin means less negative feedback to the pituitary and an increase in pituitary FSH production. More FSH means more activin—an ovarian glycoprotein that stimulates ripening of eggs—and so ovulation begins to accelerate at approximately age 36. Activin stimulates more and more eggs in the ovary to develop faster and faster.

By age 37, the ovarian egg reserve starts to decline, and—because FSH has increased—the follicle is driven to produce greater amounts of estrogen. Estrogen serum levels in fertile women average 100 pg/mL. During perimenopause, estrogen levels sometimes soar to 300, 400, or even 500 pg/mL, then may crash down to 50 to 80 pg/mL. These wild fluctuations are thought to trigger headaches, sleep disturbance, mood swings, and sexual complaints in some women.

Hysterectomy and mood symptoms. Women in their early 40s are exposed to high levels of estrogen in some menstrual cycles and low levels in others. Excess estrogen thickens the endometrium—causing heavier bleeding—and stimulates fibroid growth, which is the leading reason for hysterectomies.

One in four American women undergoes surgical menopause. The average age of the 700,000 U.S. women who undergo hysterectomy each year is 40 to 44. Women who have had a hysterectomy and have mood symptoms and sexual adjustment problems are likely to see psychiatrists earlier than women who undergo a more gradual natural menopause.

PERIMENOPAUSE: HOT FLASHES, DRY VAGINA

At ages 45 to 55, most women (90%) who have not had a hysterectomy start to cycle irregularly, tending at first toward shorter cycles and then skipping periods. Some periods are heavier and some lighter than usual. The remaining 10% of women continue to cycle regularly until their menstrual periods stop abruptly.

Many women notice temperature dysregulation during perimenopause. When they exercise, their cool-down times may double. Menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes occur when estrogen levels drop below the point that some researchers call a woman’s “estrogen set point.”

Screening for estrogen decline. When you see a patient in your office, you can often determine whether her affective symptoms—irritability, mood swings, depressed mood, and forgetfulness—might be related to estrogen decline by asking two screening questions:

- Are you having any warm flushes or hot flashes?

- Do you have vaginal dryness?

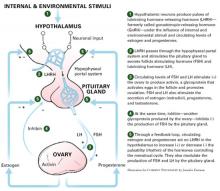

Figure 2 Normal female reproductive cycle: The rhythm of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis

LATE MENOPAUSE: ESTROGEN LOW, MOOD UP

During late menopause, approximately age 55 and older, women commonly complain of vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, sleep problems, and fatigue. Sexual interest may decrease, and a decline in sexual activity can become a problem for some couples. Asking “How is your sex life?” often will open a discussion of the couple’s sexual and emotional relationship.

Other physiologic changes caused by estrogen and androgen deficiency include thinning body hair—including pubic, auxiliary, and leg hair—decreased body odor, thinning skin, wrinkling skin, and decreasing bone density.

Table 4

Three phases of menopause: A 30-year process

| Early Ages 35 to 45 | Middle (perimenopause) Ages 46 to 55 | Late Ages 56 to 65+ |

|---|---|---|

| Physiologic changes | ||

| Ovary starts producing less inhibin 15 years before menses stop | Irregular menstrual cycles, with shorter cycles, skipping periods for 90% of women | Depletion of eggs and follicle |

| Decreased inhibin increases FSH and stimulates follicle to produce more estrogen | Some periods heavier, some lighter than usual | |

| Increased estrogen thickens endometrium and leads to heavier menstrual bleeding and increased risk of fibroids | ||

| Increased FSH produces more activin, which makes eggs develop faster and accelerates egg depletion | ||

| Lab values | ||

| Menses: Normal | Cycle shorter (24-26 days) | None for >12 months |

| FSH day 3: 10-25 mIU/mL | 20-30 mIU/mL | 50-90 mIU/mL |

| Estradiol day 3: 40-200 pg/mL | 40-200 pg/mL | 10-20 pg/mL |

| Inhibin B day 3: Varies | <45 pg/mL | 0 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Headaches, sleep disturbances, mood swings, urinary problems, sexual complaints | Warm flushes, hot flashes, night sweats in 82% of women (moderate to severe in 40%) | Vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, sleep problems, fatigue, sexual interest changes, thinning body hair (pubic, legs, axillary), decreased body odor, thinning skin, wrinkling skin, decreasing bone density, BUT mood starts to stabilize |

| FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone | ||

Urinary symptoms. Bladder problems and urinary symptoms are persistent symptoms of menopause for 75% of women. Although we psychiatrists don’t review the urinary system, it is important to remember that embarrassment because of urinary incontinence during sex may have a lot to do with a woman’s “loss of interest” in sexual intercourse.

Despite sometimes-difficult physiologic changes, the good news for many women is that mood symptoms start to stabilize after perimenopause (Table 4). Women whose moods are very responsive to hormonal fluctuations—such as those with severe premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder—sometimes get much better after menopause.

Related resources

- The Women’s Health Site. Duke Academic Program in Women’s Health. www.thewomenshealthsite.org

- Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health. www.womensmentalhealth.org

Drug brand names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sildenafil • Viagra

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Brizendine reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Burger H. Hormone replacement therapy in the post-Women’s Health Initiative era. Climacteric 2003;6(suppl 1):11-36.

2. Grodstein F, Clarkson TB, Manson JE. Understanding the divergent data on postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy. N Engl J Med 2003;348:645-50.

3. Joffe H, Hall JE, Soares CN, et al. Vasomotor symptoms are associated with depression in perimenopausal women seeking primary care. Menopause 2002;9(6):392-8.

4. Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, Cohen LS. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58(6):529-34.

5. Pearlstein T, Rosen K, Stone AB. Mood disorders and menopause. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1997;26(2):279-94.

6. Seppa N. Hormone therapy falls out of favor. Science News 2002;162:61.-

7. Nieman LK. Management of surgically hypogonadal patients unable to take sex hormone replacement therapy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2003;32(2):325-36.

8. Joffe H, Cohen LS. Estrogen, serotonin, and mood disturbance: where is the therapeutic bridge? Biol Psychiatry 1998;44(9):798-811.

9. Hays J, Ockene JK, Brunner RL, et al. Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on health-related quality of life. N Engl J Med 2003;348(19):1839-54.

10. Barton D, La VB, Loprinzi C, et al. Venlafaxine for the control of hot flashes: results of a longitudinal continuation study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2002;29(1):33-40.

11. Stearns V, Beebe KL, Iyengar M, Dube E. Paroxetine controlled release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;289(21):2827-34.

12. Soares CN, Poitras JR, Prouty J, et al. Efficacy of citalopram as a monotherapy or as an adjunctive treatment to estrogen therapy for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with depression and vasomotor symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(4):473-9.

13. Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, Perez EA, et al. Phase III evaluation of fluoxetine for treatment of hot flashes. J Clin Oncol 2002;20(6):1578-83.

14. Guttuso T, Jr, Kurlan R, McDermott MP, Kieburtz K. Gabapentin’s effects on hot flashes in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101(2):337-45.

15. Caruso S, Intelisano G, Lupo L, Agnello C. Premenopausal women affected by sexual arousal disorder treated with sildenafil: a double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled study. BJOG 2001;108(6):623-8.

16. Floter A, Nathorst-Boos J, Carlstrom K, et al. Addition of testosterone to estrogen replacement therapy in oophorectomized women: effects on sexuality and well-being. Climacteric 2002;5(4):357-65.

17. Davison SL, Davis SR. Androgens in women. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2003;85(2-5):363-6.

18. Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281:537-44.

19. Lobo RA, Rosen RC, Yang HM, et al. Comparative effects of oral esterified estrogens with and without methyltestosterone on endocrine profiles and dimensions of sexual function in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire. Fertil Steril 2003;79(6):1341-52.

20. Casson PR, Elkind-Hirsch KE, Buster JE, et al. Effect of postmenopausal estrogen replacement on circulating androgens. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90(6):995-8.

21. Bachmann G, Bancroft J, Braunstein G, et al. Female androgen insufficiency: the Princeton consensus statement on definition, classification, and assessment. Fertil Steril 2002;77(4):660-5.

22. Davis SR, Burger HG. The role of androgen therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;17(1):165-75.

23. Guay A, Davis SR. Testosterone insufficiency in women: fact or fiction? World J Urol 2002;20(2):106-10.

24. Gitlin N, Korner P, Yang HM. Liver function in postmenopausal women on estrogen-androgen hormone replacement therapy: a meta-analysis of eight clinical trials. Menopause 1999;6(3):216-24.

25. Warnock JK, Biggs CF. Reproductive life events and sexual functioning in women: case reports. CNS Spectrums 2003;8(March):3.-

26. Graham CA, Ramos R, Bancroft J, et al. The effects of steroidal contraceptives on the well-being and sexuality of women: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-centre study of combined and progestogen-only methods. Contraception 1995;52(6):363-9.

27. Guay AT. Screening for androgen deficiency in women: methodological and interpretive issues. Fertil Steril 2002;77(suppl 4):S83-8.

28. Guay AT, Jacobson J. Decreased free testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) levels in women with decreased libido. J Sex Marital Ther 2002;28(suppl 1):129-42.

29. Warnock JK, Bundren JC, Morris DW. Female hypoactive sexual desire disorder due to androgen deficiency: clinical and psychometric issues. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997;33(4):761-5.

30. Warnock JK, Clayton AH, Yates WR, Bundren JC. Sexual Energy Scale (SES): a simple valid screening tool for measuring of sexual dysfunction (poster presentation). Waikoloa, HI: North American Society for Psychosocial Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2001.

Psychiatrists are suddenly viewed as experts in treating menopause-related mood problems because of our expertise with using psychotropics. Practically overnight, the Women’s Health Initiative studies1,2 have made women and their doctors think twice about using estrogen. Instead, many are turning to psychiatric medications that have been shown to improve both mood and hot flashes—without estrogen’s potential risks.

Chances are good that after an Ob/Gyn has tried one or two psychotropics without success or with too many side effects, he or she will ask a psychiatrist to consult for certain patients. How well-prepared are you to assume this role?

If your recall of female reproductive physiology from medical school is incomplete, read on about one approach to a perimenopausal patient with depressed mood. This review can help you:

- discuss menopause knowledgeably when other physicians refer their patients to you

- provide effective, up-to-date treatments for menopause-related mood and sexual problems, using psychotropics or hormones, alone or in combination.

Irritable, with no interest in sex

Anne, age 51, has been referred to you for complaints of depressed mood and low libido. She says she has become irritable and snaps easily at her two children and her husband. She has no interest in sex, no urge to masturbate, and has had no sexual intercourse for 6 months.

Table 1

Why mood problems may occur during menopause

| Hypothesis | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Psychodynamic | Onset of menopause is a critical life event and a readjustment of self-concept |

| Sociologic | Mood changes are caused by changing life circumstances at menopause (‘empty nest,’ aging parents, health changes) |

| Domino | Depressed mood is caused by hot flashes due to declining estrogen levels, which cause chronic sleep deprivation with subsequent irritability and memory and mood changes |

| Biochemical | Decreasing estrogen leads to neurochemical changes in the brain (serotonin, dopamine, cholinergic, GABA, norepinephrine) |

Anne also complains of fatigue, dry hair and skin, warm flushes, and painful joints. She has no personal or family history of depression. She is not suicidal but states that she really doesn’t want to live anymore if “this is it.”

HOT FLASHES: A SPARK FOR DEPRESSION

Women who experience their first depression after age 50 do not fit the usual DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for depression. The Massachusetts Women’s Health Study3 found that 52% of women who experience depressed mood in the perimenopause have never had a depression before. This study also found a correlation between a longer perimenopause (>27 months) and increased risk of depressed mood. At the same time, women who have had a prior depression are 4 to 9 times more likely to experience depressive symptoms during perimenopause than those who have never had a depression before.4

The increased mood symptoms may be related to psychodynamic, sociologic, or biochemical factors, or they may result from a domino effect triggered by declining estrogen levels (Table 1). Women who experience vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes are at 4.6 times greater risk for depression than those who are hot flash-free.5

Hot flashes begin on average at age 51, which is also the average age when natural menopause begins. During menopause, most women (82%) experience hot flashes (suddenly feeling hot and sweating during the day), warm flushes (a sensation of warmth or heat spreading over the skin), and night sweats (Table 2). All women who undergo surgical menopause experience hot flashes.

Hot flashes are moderate to severe for 40% of women who experience them and persist for 5 to 15 years. By definition, moderate to severe hot flashes occur 6 to 10 or more times daily, last 6 to 10 minutes each, and are often preceded by anxiety, palpitations, irritability, nervousness, or panic.

A marriage under stress

Anne says that her husband is angry about the lack of sexual intercourse, and she feels the stress in their marriage. She also is worrying about her children leaving for college and about her mother’s ill health.

She scores 20 on the Beck Depression Inventory, which indicates that she has mild to moderate depression. Her menstrual periods remain regular, but her cycle has shortened from 29 to 24 days. She reports experiencing some hot flashes that wake her at night and says she hasn’t had a good night’s sleep in months.

Laboratory tests show FSH of 25 mIU/mL and inhibin B <45 pg/mL. Her estradiol is 80 pg/mL, which is not yet in the menopausal range of 10 to 20 pg/mL. Her thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) is normal. Her endocrinologic and reproductive diagnosis is perimenopause.

Table 2

Symptoms of menopause related to decreased estrogen

| Brain | Irritability, mood swings, depressed mood, forgetfulness, low sex interest, sleep problems, decreased well-being |

| Body | Hot flashes, vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, fatigue, joint pain, pain with orgasm, bladder dysfunction |

TREATING HOT FLASHES IMPROVES MOOD

Until July 2002, estrogen was standard treatment for controlling hot flashes in patients such as Anne. Then the Women’s Health Initiative trial reported that estrogen’s health risks—heart attack, stroke, breast cancer, and blood clots—exceeded potential benefits during 5 years of therapy. As a result, fewer women want to take estrogen,6 and many Ob/Gyns are advising patients to get through menopause without hormones if they can.

For mild hot flashes—one to three per day—patients may only need vitamin E, 800 mg/d, and deep relaxation breathing to “rev down” the sympathetic nervous system when a hot flash occurs.

For moderate to severe hot flashes—four to 10 or more per day—estrogen replacement is the most effective therapy. Estradiol, 1 mg/d, reduces hot flashes by approximately 80 to 90%.7 Many small studies have shown that patients’ mood often improves as estrogen reduces their hot flashes.8 The recent Women’s Health Initiative Quality-of-Life study, however, reported that estrogen plus progestin did not improve mood in women ages 50 to 54 with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms, even though hot flashes were reduced and sleep may have improved.9

New drugs of choice. Because of estrogen’s effectiveness in controlling hot flashes, some women and their doctors may choose to use it briefly (18 to 24 months). For others, psychotropics are becoming the drugs of choice for mood disorders with moderate to severe hot flashes.

The serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, 75 or 150 mg/d, has been shown to reduce hot flashes by 60 to 70%.10 A new trial is investigating whether duloxetine—an SNRI awaiting FDA approval—also reduces hot flashes. Other useful agents that have been shown to reduce hot flashes by 50% or more include:

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) paroxetine CR, 12.5 mg/d to 25 mg/d,11 citalopram, 20 to 60 mg/d,12 and fluoxetine, 20 mg/d13

- gabapentin, 900 mg/d.14

For hot flashes and moderate to major depression, try an SNRI or SSRI first (see Algorithm), but consider the possible effects on sexual function. All SNRIs and SSRIs have sexual side effects, including anorgasmia and loss of libido in women and men. Among the psychotropics that improve hot flashes and mood, gabapentin is the only one that does not interfere with sexual function.

Mood improves, but still no libido

You and Ann decide on a trial of the SNRI venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, to treat her hot flashes and depressed mood. Four weeks later, her hot flashes are reduced by 50% in frequency and her mood has improved (Beck Depression Inventory score is now 10). She is feeling much better and wishes to continue taking the antidepressant.

She and her husband attempted intercourse once during the past month, although she wasn’t very interested. She did not achieve orgasm, despite adequate vaginal lubrication, and she did not enjoy the experience. “I still have no libido—zero, or even less,” she says.

TREATING LOW INTEREST IN SEX

Being angry with one’s partner is the number-one reason for decreased sexual desire in all studies. Therefore, consider couples therapy for any woman complaining of loss of interest in sex. In addition, eliminate—if possible—any medications she may be taking that have known sexual side effects, such as SSRIs or beta blockers.

If the patient complains of slow or no arousal, vaginal estrogen and/or sildenafil, 25 to 50 mg 1 hour before intercourse, may be beneficial.15 Other agents the FDA is reviewing for erectile dysfunction—such as tadalafil and vardenafil—may also help arousal problems in women.

Understanding how hormones affect female sexual desire also may help you decide what advice to give Anne and how you and her Ob/Gyn coordinate her care. For example, you might treat her sexual complaints and relationship problems while the Ob/Gyn manages symptoms of the vagina, uterus, and breast.

HOW TESTOSTERONE AFFECTS SEXUAL DESIRE

Testosterone is the hormone of sexual desire in men and women. Other female androgens include androstenedione, androstenediol, 5 α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT), dihydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and its sulfate (DHEA-S). Premenopausal women produce these androgens in the ovaries (25%), adrenal glands (25%), and peripheral tissues (50%).

Average daily serum testosterone concentrations decline in women between ages 20 and 50. Lower levels are also seen with estrogen replacement therapy or oral contraceptives, lactation, anorexia nervosa, and conditions that reduce ovarian function. Women who undergo total hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy experience a sudden 50% loss of testosterone and an 80% decline in estradiol.16

Regularly menstruating women in their 40s and early 50s can have very low testosterone levels—at least 50% lower in the first 5 to 7 days of their cycles—than they had when they were in their 30s.17 The percentage of women reporting low libido increases with age until menopause, from 30% at age 30 to about 50% at age 50. Then the rate declines to 27% in women age 50 to 59.18 After natural menopause, luteinizing hormone (LH) continues to stimulate the ovarian hilar cells and interstitial cells to produce androgens, which is why many women at age 50 have adequate testosterone levels to sustain sexual desire.

Oral estrogen replacement therapy reduces bioavailable testosterone by 42% on average, which can induce androgen deficiency in a menopausal woman.19 The increased estrogen inhibits pituitary LH and decreases stimulation of the androgen-producing cells in the ovary.20

Female androgen deficiency. A number of papers have been published on female androgen deficiency syndrome (FADS).21 Its diagnosis requires symptoms of thinning pubic and axillary hair, decreased body odor, lethargy, low mood, diminished well-being, and declining libido and orgasm, despite adequate estrogen but low levels of testosterone and DHEA.

TREATING TESTOSTERONE DEFICIENCY

Benefits of replacement therapy. Replacing testosterone in women with FADS can improve mood, well-being, motivation, cognition, sexual function related to libido, orgasm, sexual fantasies, desire to masturbate, and nipple and clitoral sensitivity.22 Muscle and bone stimulation and decreased hot flashes are also reported.23 Women with androgen deficiency symptoms and low testosterone at menopause should at least be considered for physiologic testosterone replacement.

Risks of replacement therapy. Androgen replacement therapy does carry some risks, which need to be discussed with the patient. Testosterone may lower levels of beneficial HDL cholesterol, so get the cardiologist’s clearance before you give testosterone to a woman with heart disease or an HDL cholesterol level <45 mg/dL.

Algorithm Managing mood and libido problems during perimenopause

A meta-analysis of eight clinical trials found no changes in liver function in menopausal women taking 1.25 to 2.5 mg/d of methyl testosterone. Liver toxicity has been reported in men using 10-fold higher testosterone dosages.24

At the normal level of testosterone, darkening and thickening of facial hair are rare in light-skinned, light-haired women but can occur in dark-skinned, dark-haired women. Increased irritability, excess energy, argumentativeness, and aggressive behavior have been noted if testosterone levels exceed the physiologic range.

Controlled, randomized studies are needed to assess the effects of long-term use (more than 24 months) of testosterone replacement in women.

Challenges in measuring testosterone levels. Serum free testosterone is the most reliable indicator of a woman’s androgen status, but accurately measuring testosterone levels is tricky:

- Only 2% of circulating testosterone is unbound and biologically active; the rest is bound to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) or albumin.

- In ovulating women, serum testosterone levels are higher in the morning than later in the day and vary greatly within the menstrual cycle.

- Levels of androgens and estrogen are highest during the middle one-third of the cycle—on days 10 to 16, counting the first day of menstrual bleeding as day 1.25

- Oral contraceptives also decrease androgen production by the ovary and can result in low libido in some women.26

Tests developed to measure testosterone levels in men are not sensitive enough to accurately measure women’s naturally lower serum concentrations, let alone the even lower levels characteristic of female androgen or testosterone deficiency. New measurements and standardization of normal reference ranges have been developed for women complaining of low libido.27

Tests for androgen deficiency include total testosterone, free testosterone, DHEA, and DHEAS. Measuring SHBG will help you determine the free, biologically active testosterone level and calculate the Free Androgen Index (FAI) for women (Table 3).28

Table 3

Free androgen index (FAI) values in women, by age

| Replacing a woman’s bioactive testosterone to the normal free androgen index range for her age may improve low libido. | |

| How to calculate FAI | |

| Total testosterone in nmol/L (total testosterone in ng/ml X 0.0347 X 100), divided by sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in nmol/L. | |

| Age | Normal range |

| 20 to 29 | 3.72 to 4.96 |

| 30 to 39 | 2.04 to 2.96 |

| 40 to 49 | 1.98 to 2.94 |

| 50 to 59+ | 1.78 to 2.86 |

| Source: Guay et al, reference 28. | |

A candidate for testosterone therapy?

Now that Anne’s mood, sleep, and hot flashes have improved with venlafaxine, she wants help with her lack of sexual interest. You measure her testosterone and SHBG levels and find that her free androgen index is very low at 0.51 (normal range, 1.78 to 2.86).

In collaboration with her Ob/Gyn, you and Anne decide to start her on testosterone replacement therapy. You prescribe Androgel, starting at 1/7th of a 2.5-mg foil packet (0.35 mg/d of testosterone), and instruct her to rate her sexual energy daily, using a Sexual Energy Scale.

TESTOSTERONE CHOICES FOR WOMEN

Replacing a woman’s bioactive testosterone level to the normal free androgen index range for her age group may improve low libido. Some low-dose testosterone replacement options include:

- methyl testosterone sublingual pills, 0.5 mg/d, made by a compounding pharmacy or reduced dosages of oral pills made for men. If you prescribe methyl testosterone, routine lab tests will not accurately measure serum testosterone levels—unless you order the very expensive test that is specific for methyl testosterone.

- 2% vaginal cream, applied topically to increase clitoral and genital sensitivity. It may increase blood levels moderately through absorption

- Androgel, a topical testosterone approved for men. As in Anne’s case, start with 0.35 mg/d or one-seventh of the 2.5 mg packet (ask the pharmacist to place this amount in a syringe). Instruct the patient to apply the gel to hairless skin, such as inside the forearm. Effects last about 24 hours, and you can measure serum levels accurately after 14 days. Vaginal throbbing—a normal response—may occur within 30 minutes of testosterone application.

The FDA is considering other testosterone preparations—including a testosterone patch for women and a gel in female-sized doses.

Using the Sexual Energy Scale. To monitor for a therapeutic response, ask the patient to use the Sexual Energy Scale (Figure 1).29,30 Instruct her to define her “10” as the time in life when she had the most fulfilling sexual life, was the most easily aroused, had the most sexual pleasure, and the best orgasms. Her “1” would be when she felt the worst sexually and had the least desire.

Giving supplemental estrogen. If you prescribe estrogen plus testosterone (Estratest), start with Estratest HS, which contains 0.625 mg esterified estrogens and 1.25 mg of methyl testosterone. Add a progestin if the patient is postmenopausal and has not had a hysterectomy, to protect the uterus from endometrial hyperplasia.

Women with vaginal dryness also need supplemental estrogen, which can be applied vaginally (such as Premarin cream or Estrace cream). A vaginal lubricant is not sufficient to avoid age-related vaginal atrophy, which may make intercourse difficult or impossible.

Figure 1 How to use the Sexual Energy Scale to monitor response to therapy

Libido improves modestly

Ann returns in 4 weeks with gradually improving sex drive (Sexual Energy Score is now 5). She had sexual intercourse twice in the past month and didn’t “dread” it, but also did not enjoy it or reach orgasm. You have told her that venlafaxine may slow or prevent orgasm, but she wants to keep taking it. She reports that her marital relationship is improving.

You order repeat testosterone and SHBG blood levels and find her free androgen index has improved to 1.10, which is still low. You increase the Androgel dosage to 1/5th of a 2.5 mg packet (0.5 mg/day) and continue to monitor Anne’s Sexual Energy Scale ratings at monthly follow-up visits. She has set a Sexual Energy Scale rating of 7 to 8 as her target. Anne says she appreciates your help with—as she puts it—“this embarrassing problem.”

Louann Brizendine, MD

Medicine’s understanding of menopause’s physiologic and psychological consequences is changing, just as the “baby-boom” generation is navigating this passage called the change of life. Many midlife women are unaware that the menopause transition does not begin around age 50 but spans 30 years—from ages 35 to 65. Natural menopause begins 15 years before and ends 15 years after menstruation ceases—as the brain and tissues adjust to first fluctuating then decreased estrogen levels. It occurs in three phases—early menopause, perimenopause, and late menopause—that reflect a progression of hormone changes.

EARLY MENOPAUSE: OVULATION ACCELERATES

At approximately age 35, the ovaries start producing lower levels of inhibin—a glycoprotein that inhibits pituitary production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (Figure 2). Less inhibin means less negative feedback to the pituitary and an increase in pituitary FSH production. More FSH means more activin—an ovarian glycoprotein that stimulates ripening of eggs—and so ovulation begins to accelerate at approximately age 36. Activin stimulates more and more eggs in the ovary to develop faster and faster.

By age 37, the ovarian egg reserve starts to decline, and—because FSH has increased—the follicle is driven to produce greater amounts of estrogen. Estrogen serum levels in fertile women average 100 pg/mL. During perimenopause, estrogen levels sometimes soar to 300, 400, or even 500 pg/mL, then may crash down to 50 to 80 pg/mL. These wild fluctuations are thought to trigger headaches, sleep disturbance, mood swings, and sexual complaints in some women.

Hysterectomy and mood symptoms. Women in their early 40s are exposed to high levels of estrogen in some menstrual cycles and low levels in others. Excess estrogen thickens the endometrium—causing heavier bleeding—and stimulates fibroid growth, which is the leading reason for hysterectomies.

One in four American women undergoes surgical menopause. The average age of the 700,000 U.S. women who undergo hysterectomy each year is 40 to 44. Women who have had a hysterectomy and have mood symptoms and sexual adjustment problems are likely to see psychiatrists earlier than women who undergo a more gradual natural menopause.

PERIMENOPAUSE: HOT FLASHES, DRY VAGINA

At ages 45 to 55, most women (90%) who have not had a hysterectomy start to cycle irregularly, tending at first toward shorter cycles and then skipping periods. Some periods are heavier and some lighter than usual. The remaining 10% of women continue to cycle regularly until their menstrual periods stop abruptly.

Many women notice temperature dysregulation during perimenopause. When they exercise, their cool-down times may double. Menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes occur when estrogen levels drop below the point that some researchers call a woman’s “estrogen set point.”

Screening for estrogen decline. When you see a patient in your office, you can often determine whether her affective symptoms—irritability, mood swings, depressed mood, and forgetfulness—might be related to estrogen decline by asking two screening questions:

- Are you having any warm flushes or hot flashes?

- Do you have vaginal dryness?

Figure 2 Normal female reproductive cycle: The rhythm of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis

LATE MENOPAUSE: ESTROGEN LOW, MOOD UP

During late menopause, approximately age 55 and older, women commonly complain of vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, sleep problems, and fatigue. Sexual interest may decrease, and a decline in sexual activity can become a problem for some couples. Asking “How is your sex life?” often will open a discussion of the couple’s sexual and emotional relationship.

Other physiologic changes caused by estrogen and androgen deficiency include thinning body hair—including pubic, auxiliary, and leg hair—decreased body odor, thinning skin, wrinkling skin, and decreasing bone density.

Table 4

Three phases of menopause: A 30-year process

| Early Ages 35 to 45 | Middle (perimenopause) Ages 46 to 55 | Late Ages 56 to 65+ |

|---|---|---|

| Physiologic changes | ||

| Ovary starts producing less inhibin 15 years before menses stop | Irregular menstrual cycles, with shorter cycles, skipping periods for 90% of women | Depletion of eggs and follicle |

| Decreased inhibin increases FSH and stimulates follicle to produce more estrogen | Some periods heavier, some lighter than usual | |

| Increased estrogen thickens endometrium and leads to heavier menstrual bleeding and increased risk of fibroids | ||

| Increased FSH produces more activin, which makes eggs develop faster and accelerates egg depletion | ||

| Lab values | ||

| Menses: Normal | Cycle shorter (24-26 days) | None for >12 months |

| FSH day 3: 10-25 mIU/mL | 20-30 mIU/mL | 50-90 mIU/mL |

| Estradiol day 3: 40-200 pg/mL | 40-200 pg/mL | 10-20 pg/mL |

| Inhibin B day 3: Varies | <45 pg/mL | 0 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Headaches, sleep disturbances, mood swings, urinary problems, sexual complaints | Warm flushes, hot flashes, night sweats in 82% of women (moderate to severe in 40%) | Vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, sleep problems, fatigue, sexual interest changes, thinning body hair (pubic, legs, axillary), decreased body odor, thinning skin, wrinkling skin, decreasing bone density, BUT mood starts to stabilize |

| FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone | ||

Urinary symptoms. Bladder problems and urinary symptoms are persistent symptoms of menopause for 75% of women. Although we psychiatrists don’t review the urinary system, it is important to remember that embarrassment because of urinary incontinence during sex may have a lot to do with a woman’s “loss of interest” in sexual intercourse.

Despite sometimes-difficult physiologic changes, the good news for many women is that mood symptoms start to stabilize after perimenopause (Table 4). Women whose moods are very responsive to hormonal fluctuations—such as those with severe premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder—sometimes get much better after menopause.

Related resources

- The Women’s Health Site. Duke Academic Program in Women’s Health. www.thewomenshealthsite.org

- Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health. www.womensmentalhealth.org

Drug brand names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sildenafil • Viagra

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Brizendine reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Psychiatrists are suddenly viewed as experts in treating menopause-related mood problems because of our expertise with using psychotropics. Practically overnight, the Women’s Health Initiative studies1,2 have made women and their doctors think twice about using estrogen. Instead, many are turning to psychiatric medications that have been shown to improve both mood and hot flashes—without estrogen’s potential risks.

Chances are good that after an Ob/Gyn has tried one or two psychotropics without success or with too many side effects, he or she will ask a psychiatrist to consult for certain patients. How well-prepared are you to assume this role?

If your recall of female reproductive physiology from medical school is incomplete, read on about one approach to a perimenopausal patient with depressed mood. This review can help you:

- discuss menopause knowledgeably when other physicians refer their patients to you

- provide effective, up-to-date treatments for menopause-related mood and sexual problems, using psychotropics or hormones, alone or in combination.

Irritable, with no interest in sex

Anne, age 51, has been referred to you for complaints of depressed mood and low libido. She says she has become irritable and snaps easily at her two children and her husband. She has no interest in sex, no urge to masturbate, and has had no sexual intercourse for 6 months.

Table 1

Why mood problems may occur during menopause

| Hypothesis | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Psychodynamic | Onset of menopause is a critical life event and a readjustment of self-concept |

| Sociologic | Mood changes are caused by changing life circumstances at menopause (‘empty nest,’ aging parents, health changes) |

| Domino | Depressed mood is caused by hot flashes due to declining estrogen levels, which cause chronic sleep deprivation with subsequent irritability and memory and mood changes |

| Biochemical | Decreasing estrogen leads to neurochemical changes in the brain (serotonin, dopamine, cholinergic, GABA, norepinephrine) |

Anne also complains of fatigue, dry hair and skin, warm flushes, and painful joints. She has no personal or family history of depression. She is not suicidal but states that she really doesn’t want to live anymore if “this is it.”

HOT FLASHES: A SPARK FOR DEPRESSION

Women who experience their first depression after age 50 do not fit the usual DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for depression. The Massachusetts Women’s Health Study3 found that 52% of women who experience depressed mood in the perimenopause have never had a depression before. This study also found a correlation between a longer perimenopause (>27 months) and increased risk of depressed mood. At the same time, women who have had a prior depression are 4 to 9 times more likely to experience depressive symptoms during perimenopause than those who have never had a depression before.4

The increased mood symptoms may be related to psychodynamic, sociologic, or biochemical factors, or they may result from a domino effect triggered by declining estrogen levels (Table 1). Women who experience vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes are at 4.6 times greater risk for depression than those who are hot flash-free.5

Hot flashes begin on average at age 51, which is also the average age when natural menopause begins. During menopause, most women (82%) experience hot flashes (suddenly feeling hot and sweating during the day), warm flushes (a sensation of warmth or heat spreading over the skin), and night sweats (Table 2). All women who undergo surgical menopause experience hot flashes.

Hot flashes are moderate to severe for 40% of women who experience them and persist for 5 to 15 years. By definition, moderate to severe hot flashes occur 6 to 10 or more times daily, last 6 to 10 minutes each, and are often preceded by anxiety, palpitations, irritability, nervousness, or panic.

A marriage under stress

Anne says that her husband is angry about the lack of sexual intercourse, and she feels the stress in their marriage. She also is worrying about her children leaving for college and about her mother’s ill health.

She scores 20 on the Beck Depression Inventory, which indicates that she has mild to moderate depression. Her menstrual periods remain regular, but her cycle has shortened from 29 to 24 days. She reports experiencing some hot flashes that wake her at night and says she hasn’t had a good night’s sleep in months.

Laboratory tests show FSH of 25 mIU/mL and inhibin B <45 pg/mL. Her estradiol is 80 pg/mL, which is not yet in the menopausal range of 10 to 20 pg/mL. Her thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) is normal. Her endocrinologic and reproductive diagnosis is perimenopause.

Table 2

Symptoms of menopause related to decreased estrogen

| Brain | Irritability, mood swings, depressed mood, forgetfulness, low sex interest, sleep problems, decreased well-being |

| Body | Hot flashes, vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, fatigue, joint pain, pain with orgasm, bladder dysfunction |

TREATING HOT FLASHES IMPROVES MOOD

Until July 2002, estrogen was standard treatment for controlling hot flashes in patients such as Anne. Then the Women’s Health Initiative trial reported that estrogen’s health risks—heart attack, stroke, breast cancer, and blood clots—exceeded potential benefits during 5 years of therapy. As a result, fewer women want to take estrogen,6 and many Ob/Gyns are advising patients to get through menopause without hormones if they can.

For mild hot flashes—one to three per day—patients may only need vitamin E, 800 mg/d, and deep relaxation breathing to “rev down” the sympathetic nervous system when a hot flash occurs.

For moderate to severe hot flashes—four to 10 or more per day—estrogen replacement is the most effective therapy. Estradiol, 1 mg/d, reduces hot flashes by approximately 80 to 90%.7 Many small studies have shown that patients’ mood often improves as estrogen reduces their hot flashes.8 The recent Women’s Health Initiative Quality-of-Life study, however, reported that estrogen plus progestin did not improve mood in women ages 50 to 54 with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms, even though hot flashes were reduced and sleep may have improved.9

New drugs of choice. Because of estrogen’s effectiveness in controlling hot flashes, some women and their doctors may choose to use it briefly (18 to 24 months). For others, psychotropics are becoming the drugs of choice for mood disorders with moderate to severe hot flashes.

The serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, 75 or 150 mg/d, has been shown to reduce hot flashes by 60 to 70%.10 A new trial is investigating whether duloxetine—an SNRI awaiting FDA approval—also reduces hot flashes. Other useful agents that have been shown to reduce hot flashes by 50% or more include:

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) paroxetine CR, 12.5 mg/d to 25 mg/d,11 citalopram, 20 to 60 mg/d,12 and fluoxetine, 20 mg/d13

- gabapentin, 900 mg/d.14

For hot flashes and moderate to major depression, try an SNRI or SSRI first (see Algorithm), but consider the possible effects on sexual function. All SNRIs and SSRIs have sexual side effects, including anorgasmia and loss of libido in women and men. Among the psychotropics that improve hot flashes and mood, gabapentin is the only one that does not interfere with sexual function.

Mood improves, but still no libido

You and Ann decide on a trial of the SNRI venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, to treat her hot flashes and depressed mood. Four weeks later, her hot flashes are reduced by 50% in frequency and her mood has improved (Beck Depression Inventory score is now 10). She is feeling much better and wishes to continue taking the antidepressant.

She and her husband attempted intercourse once during the past month, although she wasn’t very interested. She did not achieve orgasm, despite adequate vaginal lubrication, and she did not enjoy the experience. “I still have no libido—zero, or even less,” she says.

TREATING LOW INTEREST IN SEX

Being angry with one’s partner is the number-one reason for decreased sexual desire in all studies. Therefore, consider couples therapy for any woman complaining of loss of interest in sex. In addition, eliminate—if possible—any medications she may be taking that have known sexual side effects, such as SSRIs or beta blockers.

If the patient complains of slow or no arousal, vaginal estrogen and/or sildenafil, 25 to 50 mg 1 hour before intercourse, may be beneficial.15 Other agents the FDA is reviewing for erectile dysfunction—such as tadalafil and vardenafil—may also help arousal problems in women.

Understanding how hormones affect female sexual desire also may help you decide what advice to give Anne and how you and her Ob/Gyn coordinate her care. For example, you might treat her sexual complaints and relationship problems while the Ob/Gyn manages symptoms of the vagina, uterus, and breast.

HOW TESTOSTERONE AFFECTS SEXUAL DESIRE

Testosterone is the hormone of sexual desire in men and women. Other female androgens include androstenedione, androstenediol, 5 α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT), dihydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and its sulfate (DHEA-S). Premenopausal women produce these androgens in the ovaries (25%), adrenal glands (25%), and peripheral tissues (50%).

Average daily serum testosterone concentrations decline in women between ages 20 and 50. Lower levels are also seen with estrogen replacement therapy or oral contraceptives, lactation, anorexia nervosa, and conditions that reduce ovarian function. Women who undergo total hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy experience a sudden 50% loss of testosterone and an 80% decline in estradiol.16

Regularly menstruating women in their 40s and early 50s can have very low testosterone levels—at least 50% lower in the first 5 to 7 days of their cycles—than they had when they were in their 30s.17 The percentage of women reporting low libido increases with age until menopause, from 30% at age 30 to about 50% at age 50. Then the rate declines to 27% in women age 50 to 59.18 After natural menopause, luteinizing hormone (LH) continues to stimulate the ovarian hilar cells and interstitial cells to produce androgens, which is why many women at age 50 have adequate testosterone levels to sustain sexual desire.

Oral estrogen replacement therapy reduces bioavailable testosterone by 42% on average, which can induce androgen deficiency in a menopausal woman.19 The increased estrogen inhibits pituitary LH and decreases stimulation of the androgen-producing cells in the ovary.20

Female androgen deficiency. A number of papers have been published on female androgen deficiency syndrome (FADS).21 Its diagnosis requires symptoms of thinning pubic and axillary hair, decreased body odor, lethargy, low mood, diminished well-being, and declining libido and orgasm, despite adequate estrogen but low levels of testosterone and DHEA.

TREATING TESTOSTERONE DEFICIENCY

Benefits of replacement therapy. Replacing testosterone in women with FADS can improve mood, well-being, motivation, cognition, sexual function related to libido, orgasm, sexual fantasies, desire to masturbate, and nipple and clitoral sensitivity.22 Muscle and bone stimulation and decreased hot flashes are also reported.23 Women with androgen deficiency symptoms and low testosterone at menopause should at least be considered for physiologic testosterone replacement.

Risks of replacement therapy. Androgen replacement therapy does carry some risks, which need to be discussed with the patient. Testosterone may lower levels of beneficial HDL cholesterol, so get the cardiologist’s clearance before you give testosterone to a woman with heart disease or an HDL cholesterol level <45 mg/dL.

Algorithm Managing mood and libido problems during perimenopause

A meta-analysis of eight clinical trials found no changes in liver function in menopausal women taking 1.25 to 2.5 mg/d of methyl testosterone. Liver toxicity has been reported in men using 10-fold higher testosterone dosages.24

At the normal level of testosterone, darkening and thickening of facial hair are rare in light-skinned, light-haired women but can occur in dark-skinned, dark-haired women. Increased irritability, excess energy, argumentativeness, and aggressive behavior have been noted if testosterone levels exceed the physiologic range.

Controlled, randomized studies are needed to assess the effects of long-term use (more than 24 months) of testosterone replacement in women.

Challenges in measuring testosterone levels. Serum free testosterone is the most reliable indicator of a woman’s androgen status, but accurately measuring testosterone levels is tricky:

- Only 2% of circulating testosterone is unbound and biologically active; the rest is bound to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) or albumin.

- In ovulating women, serum testosterone levels are higher in the morning than later in the day and vary greatly within the menstrual cycle.

- Levels of androgens and estrogen are highest during the middle one-third of the cycle—on days 10 to 16, counting the first day of menstrual bleeding as day 1.25

- Oral contraceptives also decrease androgen production by the ovary and can result in low libido in some women.26

Tests developed to measure testosterone levels in men are not sensitive enough to accurately measure women’s naturally lower serum concentrations, let alone the even lower levels characteristic of female androgen or testosterone deficiency. New measurements and standardization of normal reference ranges have been developed for women complaining of low libido.27

Tests for androgen deficiency include total testosterone, free testosterone, DHEA, and DHEAS. Measuring SHBG will help you determine the free, biologically active testosterone level and calculate the Free Androgen Index (FAI) for women (Table 3).28

Table 3

Free androgen index (FAI) values in women, by age

| Replacing a woman’s bioactive testosterone to the normal free androgen index range for her age may improve low libido. | |

| How to calculate FAI | |

| Total testosterone in nmol/L (total testosterone in ng/ml X 0.0347 X 100), divided by sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in nmol/L. | |

| Age | Normal range |

| 20 to 29 | 3.72 to 4.96 |

| 30 to 39 | 2.04 to 2.96 |

| 40 to 49 | 1.98 to 2.94 |

| 50 to 59+ | 1.78 to 2.86 |

| Source: Guay et al, reference 28. | |

A candidate for testosterone therapy?

Now that Anne’s mood, sleep, and hot flashes have improved with venlafaxine, she wants help with her lack of sexual interest. You measure her testosterone and SHBG levels and find that her free androgen index is very low at 0.51 (normal range, 1.78 to 2.86).

In collaboration with her Ob/Gyn, you and Anne decide to start her on testosterone replacement therapy. You prescribe Androgel, starting at 1/7th of a 2.5-mg foil packet (0.35 mg/d of testosterone), and instruct her to rate her sexual energy daily, using a Sexual Energy Scale.

TESTOSTERONE CHOICES FOR WOMEN

Replacing a woman’s bioactive testosterone level to the normal free androgen index range for her age group may improve low libido. Some low-dose testosterone replacement options include:

- methyl testosterone sublingual pills, 0.5 mg/d, made by a compounding pharmacy or reduced dosages of oral pills made for men. If you prescribe methyl testosterone, routine lab tests will not accurately measure serum testosterone levels—unless you order the very expensive test that is specific for methyl testosterone.

- 2% vaginal cream, applied topically to increase clitoral and genital sensitivity. It may increase blood levels moderately through absorption

- Androgel, a topical testosterone approved for men. As in Anne’s case, start with 0.35 mg/d or one-seventh of the 2.5 mg packet (ask the pharmacist to place this amount in a syringe). Instruct the patient to apply the gel to hairless skin, such as inside the forearm. Effects last about 24 hours, and you can measure serum levels accurately after 14 days. Vaginal throbbing—a normal response—may occur within 30 minutes of testosterone application.

The FDA is considering other testosterone preparations—including a testosterone patch for women and a gel in female-sized doses.

Using the Sexual Energy Scale. To monitor for a therapeutic response, ask the patient to use the Sexual Energy Scale (Figure 1).29,30 Instruct her to define her “10” as the time in life when she had the most fulfilling sexual life, was the most easily aroused, had the most sexual pleasure, and the best orgasms. Her “1” would be when she felt the worst sexually and had the least desire.

Giving supplemental estrogen. If you prescribe estrogen plus testosterone (Estratest), start with Estratest HS, which contains 0.625 mg esterified estrogens and 1.25 mg of methyl testosterone. Add a progestin if the patient is postmenopausal and has not had a hysterectomy, to protect the uterus from endometrial hyperplasia.

Women with vaginal dryness also need supplemental estrogen, which can be applied vaginally (such as Premarin cream or Estrace cream). A vaginal lubricant is not sufficient to avoid age-related vaginal atrophy, which may make intercourse difficult or impossible.

Figure 1 How to use the Sexual Energy Scale to monitor response to therapy

Libido improves modestly

Ann returns in 4 weeks with gradually improving sex drive (Sexual Energy Score is now 5). She had sexual intercourse twice in the past month and didn’t “dread” it, but also did not enjoy it or reach orgasm. You have told her that venlafaxine may slow or prevent orgasm, but she wants to keep taking it. She reports that her marital relationship is improving.

You order repeat testosterone and SHBG blood levels and find her free androgen index has improved to 1.10, which is still low. You increase the Androgel dosage to 1/5th of a 2.5 mg packet (0.5 mg/day) and continue to monitor Anne’s Sexual Energy Scale ratings at monthly follow-up visits. She has set a Sexual Energy Scale rating of 7 to 8 as her target. Anne says she appreciates your help with—as she puts it—“this embarrassing problem.”

Louann Brizendine, MD

Medicine’s understanding of menopause’s physiologic and psychological consequences is changing, just as the “baby-boom” generation is navigating this passage called the change of life. Many midlife women are unaware that the menopause transition does not begin around age 50 but spans 30 years—from ages 35 to 65. Natural menopause begins 15 years before and ends 15 years after menstruation ceases—as the brain and tissues adjust to first fluctuating then decreased estrogen levels. It occurs in three phases—early menopause, perimenopause, and late menopause—that reflect a progression of hormone changes.

EARLY MENOPAUSE: OVULATION ACCELERATES

At approximately age 35, the ovaries start producing lower levels of inhibin—a glycoprotein that inhibits pituitary production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (Figure 2). Less inhibin means less negative feedback to the pituitary and an increase in pituitary FSH production. More FSH means more activin—an ovarian glycoprotein that stimulates ripening of eggs—and so ovulation begins to accelerate at approximately age 36. Activin stimulates more and more eggs in the ovary to develop faster and faster.

By age 37, the ovarian egg reserve starts to decline, and—because FSH has increased—the follicle is driven to produce greater amounts of estrogen. Estrogen serum levels in fertile women average 100 pg/mL. During perimenopause, estrogen levels sometimes soar to 300, 400, or even 500 pg/mL, then may crash down to 50 to 80 pg/mL. These wild fluctuations are thought to trigger headaches, sleep disturbance, mood swings, and sexual complaints in some women.

Hysterectomy and mood symptoms. Women in their early 40s are exposed to high levels of estrogen in some menstrual cycles and low levels in others. Excess estrogen thickens the endometrium—causing heavier bleeding—and stimulates fibroid growth, which is the leading reason for hysterectomies.

One in four American women undergoes surgical menopause. The average age of the 700,000 U.S. women who undergo hysterectomy each year is 40 to 44. Women who have had a hysterectomy and have mood symptoms and sexual adjustment problems are likely to see psychiatrists earlier than women who undergo a more gradual natural menopause.

PERIMENOPAUSE: HOT FLASHES, DRY VAGINA

At ages 45 to 55, most women (90%) who have not had a hysterectomy start to cycle irregularly, tending at first toward shorter cycles and then skipping periods. Some periods are heavier and some lighter than usual. The remaining 10% of women continue to cycle regularly until their menstrual periods stop abruptly.

Many women notice temperature dysregulation during perimenopause. When they exercise, their cool-down times may double. Menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes occur when estrogen levels drop below the point that some researchers call a woman’s “estrogen set point.”

Screening for estrogen decline. When you see a patient in your office, you can often determine whether her affective symptoms—irritability, mood swings, depressed mood, and forgetfulness—might be related to estrogen decline by asking two screening questions:

- Are you having any warm flushes or hot flashes?

- Do you have vaginal dryness?

Figure 2 Normal female reproductive cycle: The rhythm of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis

LATE MENOPAUSE: ESTROGEN LOW, MOOD UP

During late menopause, approximately age 55 and older, women commonly complain of vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, sleep problems, and fatigue. Sexual interest may decrease, and a decline in sexual activity can become a problem for some couples. Asking “How is your sex life?” often will open a discussion of the couple’s sexual and emotional relationship.

Other physiologic changes caused by estrogen and androgen deficiency include thinning body hair—including pubic, auxiliary, and leg hair—decreased body odor, thinning skin, wrinkling skin, and decreasing bone density.

Table 4

Three phases of menopause: A 30-year process

| Early Ages 35 to 45 | Middle (perimenopause) Ages 46 to 55 | Late Ages 56 to 65+ |

|---|---|---|

| Physiologic changes | ||

| Ovary starts producing less inhibin 15 years before menses stop | Irregular menstrual cycles, with shorter cycles, skipping periods for 90% of women | Depletion of eggs and follicle |

| Decreased inhibin increases FSH and stimulates follicle to produce more estrogen | Some periods heavier, some lighter than usual | |

| Increased estrogen thickens endometrium and leads to heavier menstrual bleeding and increased risk of fibroids | ||

| Increased FSH produces more activin, which makes eggs develop faster and accelerates egg depletion | ||

| Lab values | ||

| Menses: Normal | Cycle shorter (24-26 days) | None for >12 months |

| FSH day 3: 10-25 mIU/mL | 20-30 mIU/mL | 50-90 mIU/mL |

| Estradiol day 3: 40-200 pg/mL | 40-200 pg/mL | 10-20 pg/mL |

| Inhibin B day 3: Varies | <45 pg/mL | 0 |

| Symptoms | ||