User login

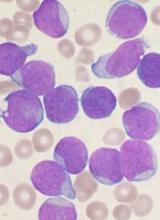

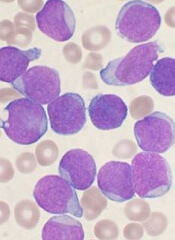

Researchers say they have developed a technique that can help them determine, at diagnosis, whether children with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) will relapse after treatment.

The method involves examining individual leukemia cells using mass cytometry.

In looking at the cells’ stage of development and signaling behavior, the researchers were able to identify a subset of malignant cells that predispose a patient to relapse.

The team described this method, which they termed “developmentally dependent predictor of relapse (DDPR),” in Nature Medicine.

Prior research suggested relapse may be driven by treatment-resistant cells that are present from the beginning of disease development.

“We wondered, can we identify those cells at the time the patient first presents to the clinic, and can we treat patients with a specific therapy to target them?” said study author Kara Davis, DO, of Stanford University in California.

Dr Davis and her colleagues used mass cytometry to analyze diagnostic bone marrow samples from 60 patients with BCP-ALL.

To pinpoint the problematic cells among the millions of cells in each patient’s sample, the researchers had to figure out how to organize the data.

“Every patient has vastly different features to their cancer,” Dr Davis said, “and we had to ask, ‘Is there any common thread between them?’”

The solution, the researchers found, was to match BCP-ALL cells and healthy B cells according to their developmental states, comparing the leukemic cells to the healthy cells.

The comparison revealed 6 features of leukemic cell populations that were associated with relapse.

Broadly, the features suggested that pro-BII cells with activated mTOR signaling were associated with relapse, as were pre-BI cells with activated and unresponsive pre-B-cell receptor signaling.

“We do not understand the mechanisms by which malignant cells from the pro-BII and pre-BI stages of development resist treatment,” Dr Davis noted.

However, she and her colleagues were able to show the leukemic cell features identified by DDPR could predict relapse in the BCP-ALL patients.

Of the 60 patients analyzed, there were 54 with at least 3 years of follow-up. The researchers divided these patients into a training cohort (n=44) and a validation cohort (n=10).

The team used an integrated cumulative/dynamic area under the curve (iAUC) and a C-statistic to assess DDPR performance in both cohorts.

In the training cohort, DDPR had an iAUC value of 0.92 and a C-statistic of 0.87. In the validation cohort, DDPR had an iAUC value of 0.85 and a C-statistic of 0.87.

The researchers also said DDPR “performed well” in predicting relapse-free survival in a retrospective analysis of both cohorts (P = 2.8 × 10−7).

Now, the researchers plan to validate DDPR in a larger number of patients and evaluate whether the same general approach could predict relapse in other cancers.

Researchers say they have developed a technique that can help them determine, at diagnosis, whether children with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) will relapse after treatment.

The method involves examining individual leukemia cells using mass cytometry.

In looking at the cells’ stage of development and signaling behavior, the researchers were able to identify a subset of malignant cells that predispose a patient to relapse.

The team described this method, which they termed “developmentally dependent predictor of relapse (DDPR),” in Nature Medicine.

Prior research suggested relapse may be driven by treatment-resistant cells that are present from the beginning of disease development.

“We wondered, can we identify those cells at the time the patient first presents to the clinic, and can we treat patients with a specific therapy to target them?” said study author Kara Davis, DO, of Stanford University in California.

Dr Davis and her colleagues used mass cytometry to analyze diagnostic bone marrow samples from 60 patients with BCP-ALL.

To pinpoint the problematic cells among the millions of cells in each patient’s sample, the researchers had to figure out how to organize the data.

“Every patient has vastly different features to their cancer,” Dr Davis said, “and we had to ask, ‘Is there any common thread between them?’”

The solution, the researchers found, was to match BCP-ALL cells and healthy B cells according to their developmental states, comparing the leukemic cells to the healthy cells.

The comparison revealed 6 features of leukemic cell populations that were associated with relapse.

Broadly, the features suggested that pro-BII cells with activated mTOR signaling were associated with relapse, as were pre-BI cells with activated and unresponsive pre-B-cell receptor signaling.

“We do not understand the mechanisms by which malignant cells from the pro-BII and pre-BI stages of development resist treatment,” Dr Davis noted.

However, she and her colleagues were able to show the leukemic cell features identified by DDPR could predict relapse in the BCP-ALL patients.

Of the 60 patients analyzed, there were 54 with at least 3 years of follow-up. The researchers divided these patients into a training cohort (n=44) and a validation cohort (n=10).

The team used an integrated cumulative/dynamic area under the curve (iAUC) and a C-statistic to assess DDPR performance in both cohorts.

In the training cohort, DDPR had an iAUC value of 0.92 and a C-statistic of 0.87. In the validation cohort, DDPR had an iAUC value of 0.85 and a C-statistic of 0.87.

The researchers also said DDPR “performed well” in predicting relapse-free survival in a retrospective analysis of both cohorts (P = 2.8 × 10−7).

Now, the researchers plan to validate DDPR in a larger number of patients and evaluate whether the same general approach could predict relapse in other cancers.

Researchers say they have developed a technique that can help them determine, at diagnosis, whether children with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) will relapse after treatment.

The method involves examining individual leukemia cells using mass cytometry.

In looking at the cells’ stage of development and signaling behavior, the researchers were able to identify a subset of malignant cells that predispose a patient to relapse.

The team described this method, which they termed “developmentally dependent predictor of relapse (DDPR),” in Nature Medicine.

Prior research suggested relapse may be driven by treatment-resistant cells that are present from the beginning of disease development.

“We wondered, can we identify those cells at the time the patient first presents to the clinic, and can we treat patients with a specific therapy to target them?” said study author Kara Davis, DO, of Stanford University in California.

Dr Davis and her colleagues used mass cytometry to analyze diagnostic bone marrow samples from 60 patients with BCP-ALL.

To pinpoint the problematic cells among the millions of cells in each patient’s sample, the researchers had to figure out how to organize the data.

“Every patient has vastly different features to their cancer,” Dr Davis said, “and we had to ask, ‘Is there any common thread between them?’”

The solution, the researchers found, was to match BCP-ALL cells and healthy B cells according to their developmental states, comparing the leukemic cells to the healthy cells.

The comparison revealed 6 features of leukemic cell populations that were associated with relapse.

Broadly, the features suggested that pro-BII cells with activated mTOR signaling were associated with relapse, as were pre-BI cells with activated and unresponsive pre-B-cell receptor signaling.

“We do not understand the mechanisms by which malignant cells from the pro-BII and pre-BI stages of development resist treatment,” Dr Davis noted.

However, she and her colleagues were able to show the leukemic cell features identified by DDPR could predict relapse in the BCP-ALL patients.

Of the 60 patients analyzed, there were 54 with at least 3 years of follow-up. The researchers divided these patients into a training cohort (n=44) and a validation cohort (n=10).

The team used an integrated cumulative/dynamic area under the curve (iAUC) and a C-statistic to assess DDPR performance in both cohorts.

In the training cohort, DDPR had an iAUC value of 0.92 and a C-statistic of 0.87. In the validation cohort, DDPR had an iAUC value of 0.85 and a C-statistic of 0.87.

The researchers also said DDPR “performed well” in predicting relapse-free survival in a retrospective analysis of both cohorts (P = 2.8 × 10−7).

Now, the researchers plan to validate DDPR in a larger number of patients and evaluate whether the same general approach could predict relapse in other cancers.