User login

SAN DIEGO – It’s not getting any easier to make the histological distinction between carcinoma in situ and simple dysplasia in a sun-damaged epidermis, but it may be getting less critical to get it right, noted Dr. John B. Campbell.

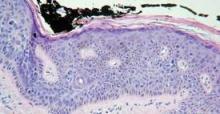

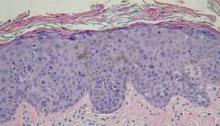

During his presentation at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery, Dr. Campbell, a Mohs pathologist in private practice in San Diego, showed slides depicting disorderly cells that typify dysplasia extending high up into the epidermis along the edges of specimens containing in situ carcinoma. "There are a lot of things that go along with dysplastic changes," he said. "The nuclei become larger; they stain darker; they have less cytoplasm so that the N/C [nuclear to cytoplasmic] ratio increases."

"At some place along the edges of the specimen you’re going to have to draw a line between in situ carcinoma and simple dysplasia. There are gradations that are somewhat subjective."

Pathologists commonly envision a line midway through the epidermis. If the dark and disorganized cells reach that point, they call it "moderate dysplasia." If they’re clumped in the lower third of the epidermis, it merits a call of "mild dysplasia," and if they extend to near the surface, it’s "severe."

"Dysplastic changes that are wall-to-wall, top-to-bottom are carcinoma in situ," he said. "You’ll need to develop criteria on your own."

In the meantime, the pressure to make the right call may be easing.

"What I’ve seen happening in the last few years is that we’re becoming less and less sensitive about dysplasia at the edges of in situ carcinomas because we can treat them so easily topically," said Dr. Campbell. Beyond watchful waiting or freezing, such regions can now be well managed with topical therapies such as Aldara (imiquimod) or Efudex (fluorouracil).

"Once we’ve cleared the unequivocal carcinoma in situ, people are letting a significant amount of dysplasia remain and then treating it in follow-up.

"There’s really no downside to [conservative or topical management] as long as the patient is reliable," he said.

Taking a careful look at the site during follow-up visits will easily reveal any cell changes that might prompt a fresh biopsy. One finding of note in such cases is the proclivity of dysplastic cells to take a downward course along appendage structures such as eccrine ducts and follicles in the epithelium. "They can go down quite deep ... maybe 2 mm deep to the surface," he said.

In his practice, Dr. Campbell and his colleagues characterize such findings as "advanced actinic keratoses," and note the presence of dysplastic cells along appendage structures.

Dr. Campbell reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – It’s not getting any easier to make the histological distinction between carcinoma in situ and simple dysplasia in a sun-damaged epidermis, but it may be getting less critical to get it right, noted Dr. John B. Campbell.

During his presentation at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery, Dr. Campbell, a Mohs pathologist in private practice in San Diego, showed slides depicting disorderly cells that typify dysplasia extending high up into the epidermis along the edges of specimens containing in situ carcinoma. "There are a lot of things that go along with dysplastic changes," he said. "The nuclei become larger; they stain darker; they have less cytoplasm so that the N/C [nuclear to cytoplasmic] ratio increases."

"At some place along the edges of the specimen you’re going to have to draw a line between in situ carcinoma and simple dysplasia. There are gradations that are somewhat subjective."

Pathologists commonly envision a line midway through the epidermis. If the dark and disorganized cells reach that point, they call it "moderate dysplasia." If they’re clumped in the lower third of the epidermis, it merits a call of "mild dysplasia," and if they extend to near the surface, it’s "severe."

"Dysplastic changes that are wall-to-wall, top-to-bottom are carcinoma in situ," he said. "You’ll need to develop criteria on your own."

In the meantime, the pressure to make the right call may be easing.

"What I’ve seen happening in the last few years is that we’re becoming less and less sensitive about dysplasia at the edges of in situ carcinomas because we can treat them so easily topically," said Dr. Campbell. Beyond watchful waiting or freezing, such regions can now be well managed with topical therapies such as Aldara (imiquimod) or Efudex (fluorouracil).

"Once we’ve cleared the unequivocal carcinoma in situ, people are letting a significant amount of dysplasia remain and then treating it in follow-up.

"There’s really no downside to [conservative or topical management] as long as the patient is reliable," he said.

Taking a careful look at the site during follow-up visits will easily reveal any cell changes that might prompt a fresh biopsy. One finding of note in such cases is the proclivity of dysplastic cells to take a downward course along appendage structures such as eccrine ducts and follicles in the epithelium. "They can go down quite deep ... maybe 2 mm deep to the surface," he said.

In his practice, Dr. Campbell and his colleagues characterize such findings as "advanced actinic keratoses," and note the presence of dysplastic cells along appendage structures.

Dr. Campbell reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – It’s not getting any easier to make the histological distinction between carcinoma in situ and simple dysplasia in a sun-damaged epidermis, but it may be getting less critical to get it right, noted Dr. John B. Campbell.

During his presentation at a meeting sponsored by the American Society for Mohs Surgery, Dr. Campbell, a Mohs pathologist in private practice in San Diego, showed slides depicting disorderly cells that typify dysplasia extending high up into the epidermis along the edges of specimens containing in situ carcinoma. "There are a lot of things that go along with dysplastic changes," he said. "The nuclei become larger; they stain darker; they have less cytoplasm so that the N/C [nuclear to cytoplasmic] ratio increases."

"At some place along the edges of the specimen you’re going to have to draw a line between in situ carcinoma and simple dysplasia. There are gradations that are somewhat subjective."

Pathologists commonly envision a line midway through the epidermis. If the dark and disorganized cells reach that point, they call it "moderate dysplasia." If they’re clumped in the lower third of the epidermis, it merits a call of "mild dysplasia," and if they extend to near the surface, it’s "severe."

"Dysplastic changes that are wall-to-wall, top-to-bottom are carcinoma in situ," he said. "You’ll need to develop criteria on your own."

In the meantime, the pressure to make the right call may be easing.

"What I’ve seen happening in the last few years is that we’re becoming less and less sensitive about dysplasia at the edges of in situ carcinomas because we can treat them so easily topically," said Dr. Campbell. Beyond watchful waiting or freezing, such regions can now be well managed with topical therapies such as Aldara (imiquimod) or Efudex (fluorouracil).

"Once we’ve cleared the unequivocal carcinoma in situ, people are letting a significant amount of dysplasia remain and then treating it in follow-up.

"There’s really no downside to [conservative or topical management] as long as the patient is reliable," he said.

Taking a careful look at the site during follow-up visits will easily reveal any cell changes that might prompt a fresh biopsy. One finding of note in such cases is the proclivity of dysplastic cells to take a downward course along appendage structures such as eccrine ducts and follicles in the epithelium. "They can go down quite deep ... maybe 2 mm deep to the surface," he said.

In his practice, Dr. Campbell and his colleagues characterize such findings as "advanced actinic keratoses," and note the presence of dysplastic cells along appendage structures.

Dr. Campbell reported no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR MOHS SURGERY