User login

The choice of entry point for gynecologic laparoscopy is critical, considering that most laparoscopic injuries occur during initial entry into the abdomen. In addition, different abdominal access points may have differing utility and efficacy depending on the patient. (The overall rate of injuries to abdominal viscera and blood vessels at the time of entry is an estimated 1 per 1,000 cases.1)

The most conventional entry point for gynecologic laparoscopic surgeries has been the umbilicus, but there are contraindications to this choice and situations in which it may not be the best access site. It is important to have knowledge of alternate entry points and techniques that consider the patient’s current pathology, anatomy, and most importantly, surgical history to better facilitate a safe initial entry.

The left upper quadrant (LUQ) has been described as a preferred alternate site to the umbilicus, and some gynecologic surgeons even consider it as a routine mode of entry.2 In our practice, LUQ entry is a safe and commonly used technique that is chosen primarily based on a patient’s history of a midline vertical incision, the presence of abdominal mesh from a prior umbilical hernia repair, or repeated cesarean sections.

Our technique for LUQ entry is a modification of the traditional approach that employs Palmer’s point – the entry point described by Raoul Palmer, MD, in 1974 as 3-4 cm below the left subcostal margin at the midclavicular line.3 We choose to enter at the midclavicular level and directly under the last rib.

When the umbilicus is problematic

The umbilicus is a favored entry point not only for its operative access to pelvic structures but also because – in the absence of obesity – it has no or little subcutaneous fat and, therefore, provides the shortest distance from skin to peritoneum.

However, adhesive disease from a prior laparotomy involving the umbilicus is a risk factor for bowel injury during umbilical entry (direct trocar, Veress needle, or open technique). In a 1995 review of 360 women undergoing operative laparoscopy after a previous laparotomy, Brill et al. reported umbilical adhesions in 27% of those with prior horizontal suprapubic (Pfannenstiel) incisions, in 55% of those with prior incisions in the midline below the umbilicus, and 67% of those with prior midline incisions above the umbilicus.4

Of the 259 patients whose prior laparotomy was for gynecologic surgery (as opposed to obstetric or general surgery) adhesions were present in 70% of those who had midline incisions. (Direct injury to adherent omentum and bowel occurred during laparoscopic procedures in 21% of all women.)

Since the Brill paper, other studies have similarly reported significant adhesion rate, especially after midline incisions. For instance, one French study of patients undergoing laparoscopy reported umbilical adhesions in 51.7% of 89 patients who had previous laparotomy with a midline incision.5

Prior umbilical laparoscopy is not a risk factor for umbilical entry unless a hernia repair with mesh was performed at the umbilicus. Umbilical adhesions have been reported to occur in up to 15% of women who have had prior laparoscopic surgery, with more adhesions associated with larger trocar use (specifically 12-mm trocars).1 Still, the rate of those adhesions was very low.

Obesity is not necessarily a contraindication to umbilical entry; however, it can make successful entry more difficult, particularly in those with central obesity and a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat. It can be difficult in such cases to know when peritoneal access is achieved. Extra-long Veress needles or trocars may be needed, and it is important to enter the abdomen at a 90° angle to minimize risk to the great vessel vasculature.

LUQ entry is often a reliable alternative when central obesity is significant or when umbilical access proves to be difficult. Certainly, the subcutaneous fat layer is thinner at the LUQ than at the umbilicus, and in patients whose umbilicus is pulled very caudal because of a large pannus, the LUQ will also provide a better location for visualization of pelvic anatomy and for easier entry.

We still use umbilical entry in most patients with obesity, but if we are unsuccessful after two to three attempts, we proceed to the LUQ (barring any contraindications to this site).

LUQ entry: Our approach, contraindications

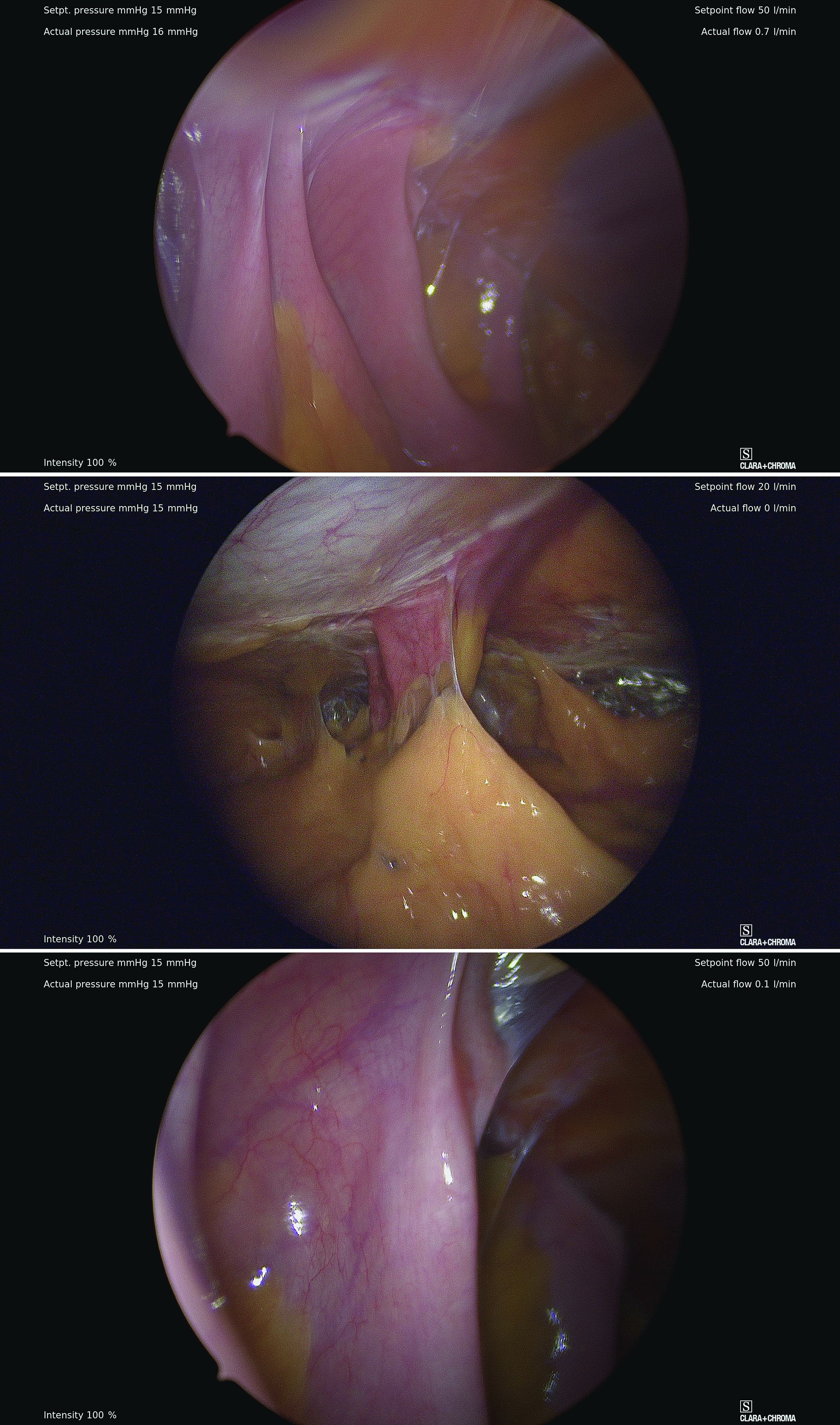

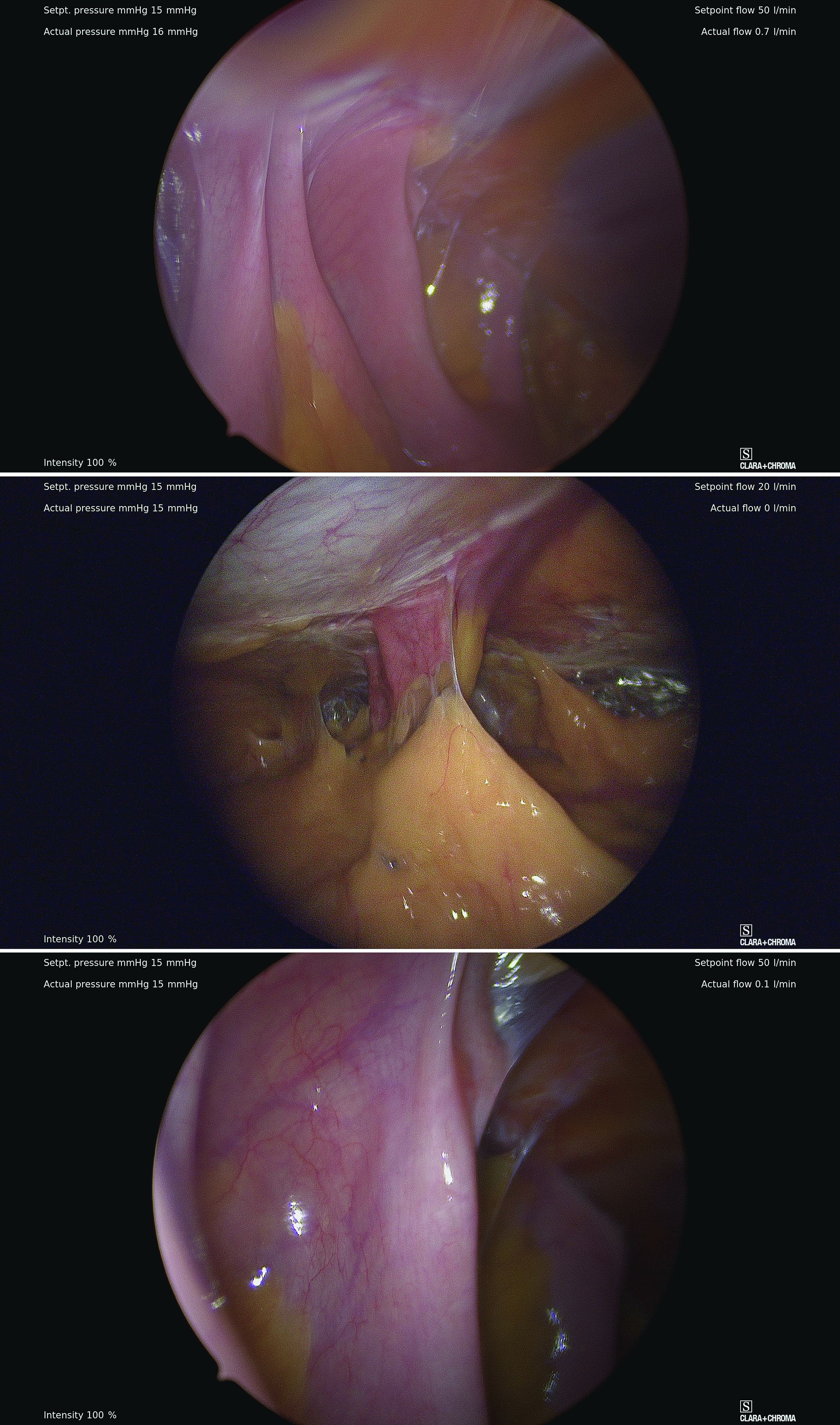

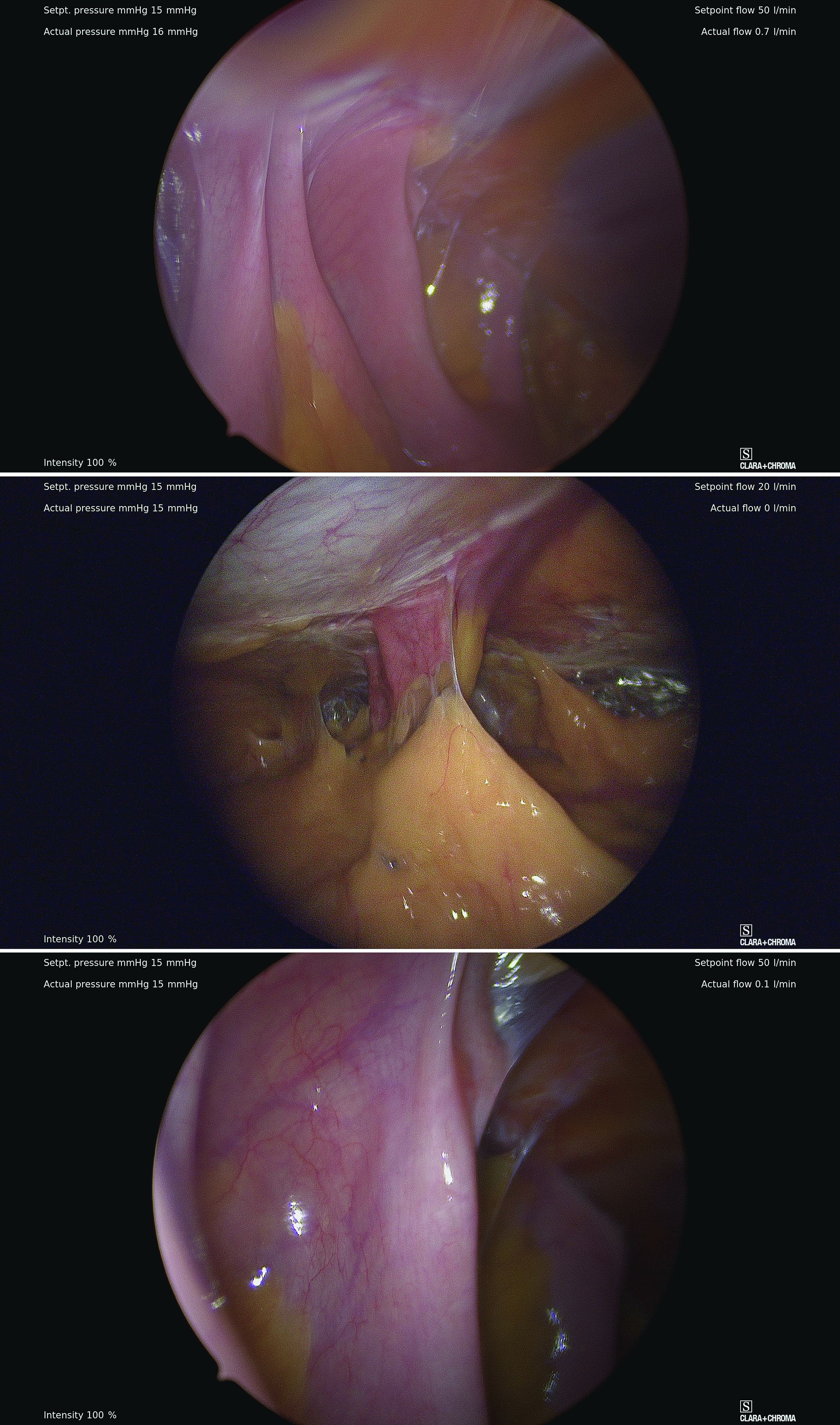

By entering at the midclavicular level and directly under the bottom of the rib cage, rather than 2-3 cm below the last rib as in traditional Palmer’s point LUQ entry, we benefit from the tenting up of the peritoneum by the last rib. Having space between the peritoneum and underlying omentum and stomach can facilitate an easier entry, as shown in the video.

We primarily utilize the Veress needle for entry. The needle is inserted directly perpendicular to the fascia, or at a slight angle toward the umbilicus. After the abdomen is insufflated to 15 mm Hg, we proceed with a visual peritoneal entry using a 5-mm trocar with a clear tip, which allows us to visualize both layers of fascia, and subsequently the peritoneum, as the trocar is advanced.

The fascia is not fused, so we can expect to feel three “pops” as the needle (or trocar) passes through the aponeuroses of the internal and external obliques, the aponeuroses of the internal oblique and transversus, and the peritoneum.

While successful peritoneal entry with umbilical access is generally confirmed with an intraperitoneal pressure measuring less than 7 mm Hg (which varies depending on abdominal wall thickness and adiposity), we have found that the opening pressure with LUQ entry is slightly higher. A recently published Canadian guideline for gynecologic laparoscopic entry recommends that an initial Veress intraperitoneal pressure of 10 mm Hg or below be considered an indicator of successful entry, regardless of the patient’s body habitus.1

LUQ entry can be helpful for surgeries involving large pelvic masses, for which there is little or no space to enter at the umbilicus or to optimally view the pathology. Utilizing the LUQ not only allows for an unobstructed entry and optimal viewing but also may become an extra operative port that can be used for the camera, allowing both surgeons to operate with two hands – a four-port technique. It also allows the surgeon to use a larger diameter port at the umbilicus without concern for cosmetics.

Additionally, there is a school of thought that LUQ entry is overall more successful, requiring less conversion to alternative sites and fewer attempts. This success may result from the presence of less adhesive disease in the LUQ, as well as clearer visualization of the anatomy while entering and confidence in entering the intraperitoneal space.

A prerequisite for LUQ entry is that the stomach be decompressed through placement of an oral gastric or nasogastric tube and suctioning of all gastric contents. An inability to decompress the stomach is a contraindication to LUQ entry, as is a history of splenectomy, an enlarged liver, gastric bypass surgery, or upper abdominal surgery.

Entry techniques, alternate sites

No single entry site or technique has been proven to be universally safer than another. A 2019 Cochrane review of laparoscopic entry techniques noted an advantage of direct trocar entry over Veress-needle entry for failed entry but concluded that, overall, evidence was insufficient to support the use of one entry technique over another to decrease complication rates.6

A more recently published review of randomized controlled trials, Cochrane reviews, and older descriptive accounts similarly concluded that, between the Veress needle (the oldest described technique), direct trocar insertion, and open entry (Hasson), there is no good evidence to suggest that any of these methods is universally superior.2 Surgeon comfort is, therefore, an important factor.

Regarding entry sites, we advocate use of the LUQ as an advantageous alternative site for access, but there are several other approaches described in the literature. These include right upper quadrant entry; the Lee Huang point, which is about 10 cm below the xiphoid; and uncommonly, vaginal, either posterior to the uterus into the pouch of Douglas or through the uterine fundus.2

The right upper quadrant approach is included in a recent video review in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology of safe entry techniques, along with umbilicus, LUQ, and supraumbilical entry.7

Another described entry site is the “Jain point,” located at the intersection of a vertical line drawn 2.5 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, up to the level of the umbilicus, and a horizontal line at the upper margin of the umbilicus. In a retrospective study of 7,802 cases involving this method, the authors reported only one significant entry complication. Patients in the study had a wide range of BMIs and previous surgeries.8

With respect to entry techniques, we facilitate the Veress entry technique described by Frank E. Loeffler, MD, in the mid-1970s, unless there are contraindications such as second-trimester pregnancy. For umbilical entry, we first use a Kocher clamp to grasp the base of the umbilicus and then evert it. Using two towel clips, the surgeon and assistant apply countertraction by grasping the skin and fat on either side of the umbilicus. A horizontal incision is then made directly on the base of the umbilicus. The towel clips are used to elevate the anterior abdominal wall, and the Veress needle is attached to insufflation tubing, then inserted into the abdomen.

Alternatively, direct entry involves incising the skin, placing a laparoscope in a visual entry trocar, and directly visualizing each layer as the abdomen is entered. Once the trocar is intraperitoneal, insufflation is started.

In open laparoscopic/Hasson entry, the umbilical skin is incised, and the subcutaneous fat is dissected down until the rectal fascia is visualized. The fascia is then incised, the peritoneum is entered bluntly, and the Hasson trocar is placed. Insufflation is attached, and the laparoscope is inserted.

Dr. Sasaki is a partner, and Dr. McKenna is an AAGL MIGS fellow, in the private practice of Charles E. Miller, MD, & Associates in Chicago. They reported that they have no disclosures.

References

1. Vilos GA et al. J Obstet Gyneacol Can. 2021;43(3):376-89.

2. Recknagel JD and Goodman LR. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):467-74.

3. Palmer R. J Reprod Med. 1974;13:1-5.

4. Brill AI et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(2):269-72.

5. Audebert AJ and Gomel V. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(3):631-5.

6. Ahmad G et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;1:CD006583.

7. Patzkowsky KE et al. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):386.

8. Nutan J et al. Updates in Surgery. 2021;73(6):2321-9.

The choice of entry point for gynecologic laparoscopy is critical, considering that most laparoscopic injuries occur during initial entry into the abdomen. In addition, different abdominal access points may have differing utility and efficacy depending on the patient. (The overall rate of injuries to abdominal viscera and blood vessels at the time of entry is an estimated 1 per 1,000 cases.1)

The most conventional entry point for gynecologic laparoscopic surgeries has been the umbilicus, but there are contraindications to this choice and situations in which it may not be the best access site. It is important to have knowledge of alternate entry points and techniques that consider the patient’s current pathology, anatomy, and most importantly, surgical history to better facilitate a safe initial entry.

The left upper quadrant (LUQ) has been described as a preferred alternate site to the umbilicus, and some gynecologic surgeons even consider it as a routine mode of entry.2 In our practice, LUQ entry is a safe and commonly used technique that is chosen primarily based on a patient’s history of a midline vertical incision, the presence of abdominal mesh from a prior umbilical hernia repair, or repeated cesarean sections.

Our technique for LUQ entry is a modification of the traditional approach that employs Palmer’s point – the entry point described by Raoul Palmer, MD, in 1974 as 3-4 cm below the left subcostal margin at the midclavicular line.3 We choose to enter at the midclavicular level and directly under the last rib.

When the umbilicus is problematic

The umbilicus is a favored entry point not only for its operative access to pelvic structures but also because – in the absence of obesity – it has no or little subcutaneous fat and, therefore, provides the shortest distance from skin to peritoneum.

However, adhesive disease from a prior laparotomy involving the umbilicus is a risk factor for bowel injury during umbilical entry (direct trocar, Veress needle, or open technique). In a 1995 review of 360 women undergoing operative laparoscopy after a previous laparotomy, Brill et al. reported umbilical adhesions in 27% of those with prior horizontal suprapubic (Pfannenstiel) incisions, in 55% of those with prior incisions in the midline below the umbilicus, and 67% of those with prior midline incisions above the umbilicus.4

Of the 259 patients whose prior laparotomy was for gynecologic surgery (as opposed to obstetric or general surgery) adhesions were present in 70% of those who had midline incisions. (Direct injury to adherent omentum and bowel occurred during laparoscopic procedures in 21% of all women.)

Since the Brill paper, other studies have similarly reported significant adhesion rate, especially after midline incisions. For instance, one French study of patients undergoing laparoscopy reported umbilical adhesions in 51.7% of 89 patients who had previous laparotomy with a midline incision.5

Prior umbilical laparoscopy is not a risk factor for umbilical entry unless a hernia repair with mesh was performed at the umbilicus. Umbilical adhesions have been reported to occur in up to 15% of women who have had prior laparoscopic surgery, with more adhesions associated with larger trocar use (specifically 12-mm trocars).1 Still, the rate of those adhesions was very low.

Obesity is not necessarily a contraindication to umbilical entry; however, it can make successful entry more difficult, particularly in those with central obesity and a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat. It can be difficult in such cases to know when peritoneal access is achieved. Extra-long Veress needles or trocars may be needed, and it is important to enter the abdomen at a 90° angle to minimize risk to the great vessel vasculature.

LUQ entry is often a reliable alternative when central obesity is significant or when umbilical access proves to be difficult. Certainly, the subcutaneous fat layer is thinner at the LUQ than at the umbilicus, and in patients whose umbilicus is pulled very caudal because of a large pannus, the LUQ will also provide a better location for visualization of pelvic anatomy and for easier entry.

We still use umbilical entry in most patients with obesity, but if we are unsuccessful after two to three attempts, we proceed to the LUQ (barring any contraindications to this site).

LUQ entry: Our approach, contraindications

By entering at the midclavicular level and directly under the bottom of the rib cage, rather than 2-3 cm below the last rib as in traditional Palmer’s point LUQ entry, we benefit from the tenting up of the peritoneum by the last rib. Having space between the peritoneum and underlying omentum and stomach can facilitate an easier entry, as shown in the video.

We primarily utilize the Veress needle for entry. The needle is inserted directly perpendicular to the fascia, or at a slight angle toward the umbilicus. After the abdomen is insufflated to 15 mm Hg, we proceed with a visual peritoneal entry using a 5-mm trocar with a clear tip, which allows us to visualize both layers of fascia, and subsequently the peritoneum, as the trocar is advanced.

The fascia is not fused, so we can expect to feel three “pops” as the needle (or trocar) passes through the aponeuroses of the internal and external obliques, the aponeuroses of the internal oblique and transversus, and the peritoneum.

While successful peritoneal entry with umbilical access is generally confirmed with an intraperitoneal pressure measuring less than 7 mm Hg (which varies depending on abdominal wall thickness and adiposity), we have found that the opening pressure with LUQ entry is slightly higher. A recently published Canadian guideline for gynecologic laparoscopic entry recommends that an initial Veress intraperitoneal pressure of 10 mm Hg or below be considered an indicator of successful entry, regardless of the patient’s body habitus.1

LUQ entry can be helpful for surgeries involving large pelvic masses, for which there is little or no space to enter at the umbilicus or to optimally view the pathology. Utilizing the LUQ not only allows for an unobstructed entry and optimal viewing but also may become an extra operative port that can be used for the camera, allowing both surgeons to operate with two hands – a four-port technique. It also allows the surgeon to use a larger diameter port at the umbilicus without concern for cosmetics.

Additionally, there is a school of thought that LUQ entry is overall more successful, requiring less conversion to alternative sites and fewer attempts. This success may result from the presence of less adhesive disease in the LUQ, as well as clearer visualization of the anatomy while entering and confidence in entering the intraperitoneal space.

A prerequisite for LUQ entry is that the stomach be decompressed through placement of an oral gastric or nasogastric tube and suctioning of all gastric contents. An inability to decompress the stomach is a contraindication to LUQ entry, as is a history of splenectomy, an enlarged liver, gastric bypass surgery, or upper abdominal surgery.

Entry techniques, alternate sites

No single entry site or technique has been proven to be universally safer than another. A 2019 Cochrane review of laparoscopic entry techniques noted an advantage of direct trocar entry over Veress-needle entry for failed entry but concluded that, overall, evidence was insufficient to support the use of one entry technique over another to decrease complication rates.6

A more recently published review of randomized controlled trials, Cochrane reviews, and older descriptive accounts similarly concluded that, between the Veress needle (the oldest described technique), direct trocar insertion, and open entry (Hasson), there is no good evidence to suggest that any of these methods is universally superior.2 Surgeon comfort is, therefore, an important factor.

Regarding entry sites, we advocate use of the LUQ as an advantageous alternative site for access, but there are several other approaches described in the literature. These include right upper quadrant entry; the Lee Huang point, which is about 10 cm below the xiphoid; and uncommonly, vaginal, either posterior to the uterus into the pouch of Douglas or through the uterine fundus.2

The right upper quadrant approach is included in a recent video review in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology of safe entry techniques, along with umbilicus, LUQ, and supraumbilical entry.7

Another described entry site is the “Jain point,” located at the intersection of a vertical line drawn 2.5 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, up to the level of the umbilicus, and a horizontal line at the upper margin of the umbilicus. In a retrospective study of 7,802 cases involving this method, the authors reported only one significant entry complication. Patients in the study had a wide range of BMIs and previous surgeries.8

With respect to entry techniques, we facilitate the Veress entry technique described by Frank E. Loeffler, MD, in the mid-1970s, unless there are contraindications such as second-trimester pregnancy. For umbilical entry, we first use a Kocher clamp to grasp the base of the umbilicus and then evert it. Using two towel clips, the surgeon and assistant apply countertraction by grasping the skin and fat on either side of the umbilicus. A horizontal incision is then made directly on the base of the umbilicus. The towel clips are used to elevate the anterior abdominal wall, and the Veress needle is attached to insufflation tubing, then inserted into the abdomen.

Alternatively, direct entry involves incising the skin, placing a laparoscope in a visual entry trocar, and directly visualizing each layer as the abdomen is entered. Once the trocar is intraperitoneal, insufflation is started.

In open laparoscopic/Hasson entry, the umbilical skin is incised, and the subcutaneous fat is dissected down until the rectal fascia is visualized. The fascia is then incised, the peritoneum is entered bluntly, and the Hasson trocar is placed. Insufflation is attached, and the laparoscope is inserted.

Dr. Sasaki is a partner, and Dr. McKenna is an AAGL MIGS fellow, in the private practice of Charles E. Miller, MD, & Associates in Chicago. They reported that they have no disclosures.

References

1. Vilos GA et al. J Obstet Gyneacol Can. 2021;43(3):376-89.

2. Recknagel JD and Goodman LR. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):467-74.

3. Palmer R. J Reprod Med. 1974;13:1-5.

4. Brill AI et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(2):269-72.

5. Audebert AJ and Gomel V. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(3):631-5.

6. Ahmad G et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;1:CD006583.

7. Patzkowsky KE et al. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):386.

8. Nutan J et al. Updates in Surgery. 2021;73(6):2321-9.

The choice of entry point for gynecologic laparoscopy is critical, considering that most laparoscopic injuries occur during initial entry into the abdomen. In addition, different abdominal access points may have differing utility and efficacy depending on the patient. (The overall rate of injuries to abdominal viscera and blood vessels at the time of entry is an estimated 1 per 1,000 cases.1)

The most conventional entry point for gynecologic laparoscopic surgeries has been the umbilicus, but there are contraindications to this choice and situations in which it may not be the best access site. It is important to have knowledge of alternate entry points and techniques that consider the patient’s current pathology, anatomy, and most importantly, surgical history to better facilitate a safe initial entry.

The left upper quadrant (LUQ) has been described as a preferred alternate site to the umbilicus, and some gynecologic surgeons even consider it as a routine mode of entry.2 In our practice, LUQ entry is a safe and commonly used technique that is chosen primarily based on a patient’s history of a midline vertical incision, the presence of abdominal mesh from a prior umbilical hernia repair, or repeated cesarean sections.

Our technique for LUQ entry is a modification of the traditional approach that employs Palmer’s point – the entry point described by Raoul Palmer, MD, in 1974 as 3-4 cm below the left subcostal margin at the midclavicular line.3 We choose to enter at the midclavicular level and directly under the last rib.

When the umbilicus is problematic

The umbilicus is a favored entry point not only for its operative access to pelvic structures but also because – in the absence of obesity – it has no or little subcutaneous fat and, therefore, provides the shortest distance from skin to peritoneum.

However, adhesive disease from a prior laparotomy involving the umbilicus is a risk factor for bowel injury during umbilical entry (direct trocar, Veress needle, or open technique). In a 1995 review of 360 women undergoing operative laparoscopy after a previous laparotomy, Brill et al. reported umbilical adhesions in 27% of those with prior horizontal suprapubic (Pfannenstiel) incisions, in 55% of those with prior incisions in the midline below the umbilicus, and 67% of those with prior midline incisions above the umbilicus.4

Of the 259 patients whose prior laparotomy was for gynecologic surgery (as opposed to obstetric or general surgery) adhesions were present in 70% of those who had midline incisions. (Direct injury to adherent omentum and bowel occurred during laparoscopic procedures in 21% of all women.)

Since the Brill paper, other studies have similarly reported significant adhesion rate, especially after midline incisions. For instance, one French study of patients undergoing laparoscopy reported umbilical adhesions in 51.7% of 89 patients who had previous laparotomy with a midline incision.5

Prior umbilical laparoscopy is not a risk factor for umbilical entry unless a hernia repair with mesh was performed at the umbilicus. Umbilical adhesions have been reported to occur in up to 15% of women who have had prior laparoscopic surgery, with more adhesions associated with larger trocar use (specifically 12-mm trocars).1 Still, the rate of those adhesions was very low.

Obesity is not necessarily a contraindication to umbilical entry; however, it can make successful entry more difficult, particularly in those with central obesity and a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat. It can be difficult in such cases to know when peritoneal access is achieved. Extra-long Veress needles or trocars may be needed, and it is important to enter the abdomen at a 90° angle to minimize risk to the great vessel vasculature.

LUQ entry is often a reliable alternative when central obesity is significant or when umbilical access proves to be difficult. Certainly, the subcutaneous fat layer is thinner at the LUQ than at the umbilicus, and in patients whose umbilicus is pulled very caudal because of a large pannus, the LUQ will also provide a better location for visualization of pelvic anatomy and for easier entry.

We still use umbilical entry in most patients with obesity, but if we are unsuccessful after two to three attempts, we proceed to the LUQ (barring any contraindications to this site).

LUQ entry: Our approach, contraindications

By entering at the midclavicular level and directly under the bottom of the rib cage, rather than 2-3 cm below the last rib as in traditional Palmer’s point LUQ entry, we benefit from the tenting up of the peritoneum by the last rib. Having space between the peritoneum and underlying omentum and stomach can facilitate an easier entry, as shown in the video.

We primarily utilize the Veress needle for entry. The needle is inserted directly perpendicular to the fascia, or at a slight angle toward the umbilicus. After the abdomen is insufflated to 15 mm Hg, we proceed with a visual peritoneal entry using a 5-mm trocar with a clear tip, which allows us to visualize both layers of fascia, and subsequently the peritoneum, as the trocar is advanced.

The fascia is not fused, so we can expect to feel three “pops” as the needle (or trocar) passes through the aponeuroses of the internal and external obliques, the aponeuroses of the internal oblique and transversus, and the peritoneum.

While successful peritoneal entry with umbilical access is generally confirmed with an intraperitoneal pressure measuring less than 7 mm Hg (which varies depending on abdominal wall thickness and adiposity), we have found that the opening pressure with LUQ entry is slightly higher. A recently published Canadian guideline for gynecologic laparoscopic entry recommends that an initial Veress intraperitoneal pressure of 10 mm Hg or below be considered an indicator of successful entry, regardless of the patient’s body habitus.1

LUQ entry can be helpful for surgeries involving large pelvic masses, for which there is little or no space to enter at the umbilicus or to optimally view the pathology. Utilizing the LUQ not only allows for an unobstructed entry and optimal viewing but also may become an extra operative port that can be used for the camera, allowing both surgeons to operate with two hands – a four-port technique. It also allows the surgeon to use a larger diameter port at the umbilicus without concern for cosmetics.

Additionally, there is a school of thought that LUQ entry is overall more successful, requiring less conversion to alternative sites and fewer attempts. This success may result from the presence of less adhesive disease in the LUQ, as well as clearer visualization of the anatomy while entering and confidence in entering the intraperitoneal space.

A prerequisite for LUQ entry is that the stomach be decompressed through placement of an oral gastric or nasogastric tube and suctioning of all gastric contents. An inability to decompress the stomach is a contraindication to LUQ entry, as is a history of splenectomy, an enlarged liver, gastric bypass surgery, or upper abdominal surgery.

Entry techniques, alternate sites

No single entry site or technique has been proven to be universally safer than another. A 2019 Cochrane review of laparoscopic entry techniques noted an advantage of direct trocar entry over Veress-needle entry for failed entry but concluded that, overall, evidence was insufficient to support the use of one entry technique over another to decrease complication rates.6

A more recently published review of randomized controlled trials, Cochrane reviews, and older descriptive accounts similarly concluded that, between the Veress needle (the oldest described technique), direct trocar insertion, and open entry (Hasson), there is no good evidence to suggest that any of these methods is universally superior.2 Surgeon comfort is, therefore, an important factor.

Regarding entry sites, we advocate use of the LUQ as an advantageous alternative site for access, but there are several other approaches described in the literature. These include right upper quadrant entry; the Lee Huang point, which is about 10 cm below the xiphoid; and uncommonly, vaginal, either posterior to the uterus into the pouch of Douglas or through the uterine fundus.2

The right upper quadrant approach is included in a recent video review in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology of safe entry techniques, along with umbilicus, LUQ, and supraumbilical entry.7

Another described entry site is the “Jain point,” located at the intersection of a vertical line drawn 2.5 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, up to the level of the umbilicus, and a horizontal line at the upper margin of the umbilicus. In a retrospective study of 7,802 cases involving this method, the authors reported only one significant entry complication. Patients in the study had a wide range of BMIs and previous surgeries.8

With respect to entry techniques, we facilitate the Veress entry technique described by Frank E. Loeffler, MD, in the mid-1970s, unless there are contraindications such as second-trimester pregnancy. For umbilical entry, we first use a Kocher clamp to grasp the base of the umbilicus and then evert it. Using two towel clips, the surgeon and assistant apply countertraction by grasping the skin and fat on either side of the umbilicus. A horizontal incision is then made directly on the base of the umbilicus. The towel clips are used to elevate the anterior abdominal wall, and the Veress needle is attached to insufflation tubing, then inserted into the abdomen.

Alternatively, direct entry involves incising the skin, placing a laparoscope in a visual entry trocar, and directly visualizing each layer as the abdomen is entered. Once the trocar is intraperitoneal, insufflation is started.

In open laparoscopic/Hasson entry, the umbilical skin is incised, and the subcutaneous fat is dissected down until the rectal fascia is visualized. The fascia is then incised, the peritoneum is entered bluntly, and the Hasson trocar is placed. Insufflation is attached, and the laparoscope is inserted.

Dr. Sasaki is a partner, and Dr. McKenna is an AAGL MIGS fellow, in the private practice of Charles E. Miller, MD, & Associates in Chicago. They reported that they have no disclosures.

References

1. Vilos GA et al. J Obstet Gyneacol Can. 2021;43(3):376-89.

2. Recknagel JD and Goodman LR. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):467-74.

3. Palmer R. J Reprod Med. 1974;13:1-5.

4. Brill AI et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(2):269-72.

5. Audebert AJ and Gomel V. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(3):631-5.

6. Ahmad G et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;1:CD006583.

7. Patzkowsky KE et al. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):386.

8. Nutan J et al. Updates in Surgery. 2021;73(6):2321-9.