User login

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re an epidemiologist trying to explore whether some exposure is a risk factor for a disease, you can run into a tough problem when your exposure of interest is highly correlated with another risk factor for the disease. For decades, this stymied investigations into the link, if any, between marijuana use and cardiovascular disease because, for decades, most people who used marijuana in some way also smoked cigarettes — which is a very clear risk factor for heart disease.

But the times they are a-changing.

Thanks to the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in many states, and even broader social trends, there is now a large population of people who use marijuana but do not use cigarettes. That means we can start to determine whether marijuana use is an independent risk factor for heart disease.

And this week, we have the largest study yet to attempt to answer that question, though, as I’ll explain momentarily, the smoke hasn’t entirely cleared yet.

The centerpiece of the study we are discussing this week, “Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults,” which appeared in the Journal of the American Heart Association, is the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1984 that gathers data on all sorts of stuff that we do to ourselves: our drinking habits, our smoking habits, and, more recently, our marijuana habits.

The paper combines annual data from 2016 to 2020 representing 27 states and two US territories for a total sample size of more than 430,000 individuals. The key exposure? Marijuana use, which was coded as the number of days of marijuana use in the past 30 days. The key outcome? Coronary heart disease, collected through questions such as “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had a heart attack?”

Right away you might detect a couple of problems here. But let me show you the results before we worry about what they mean.

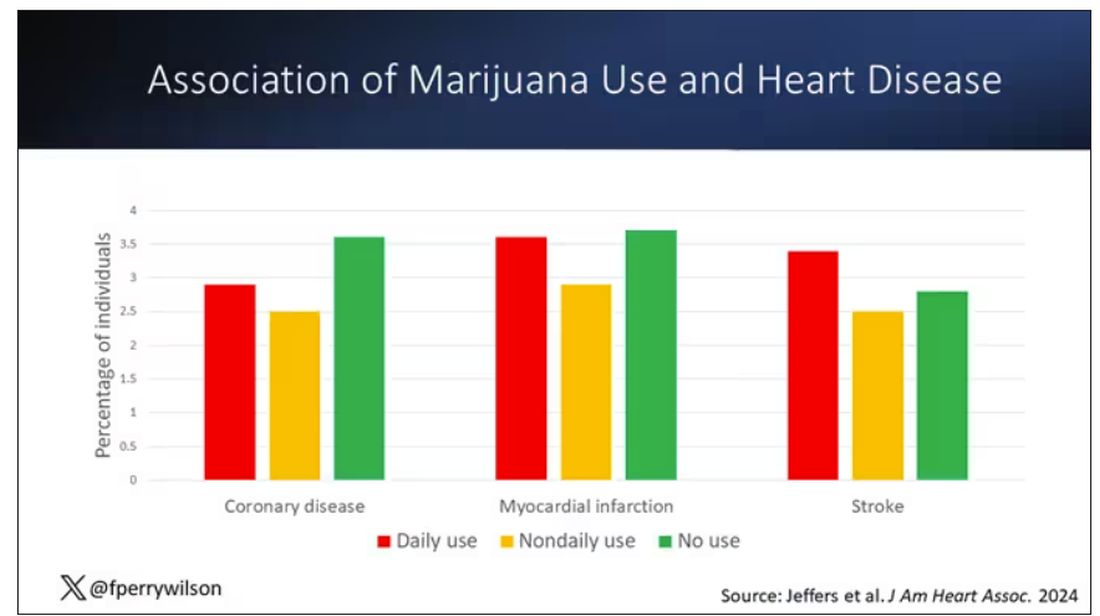

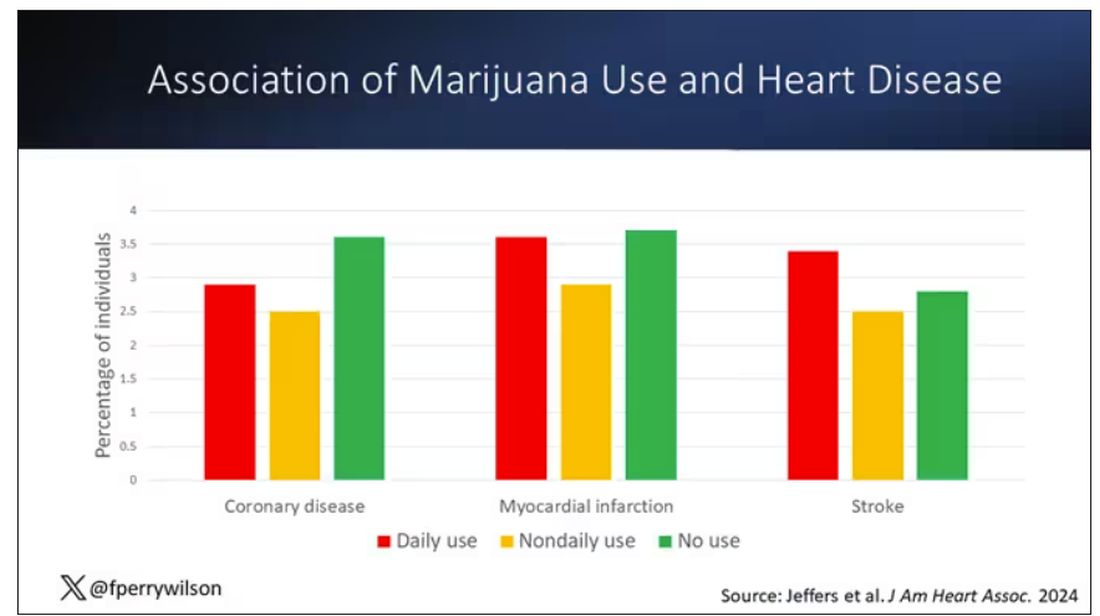

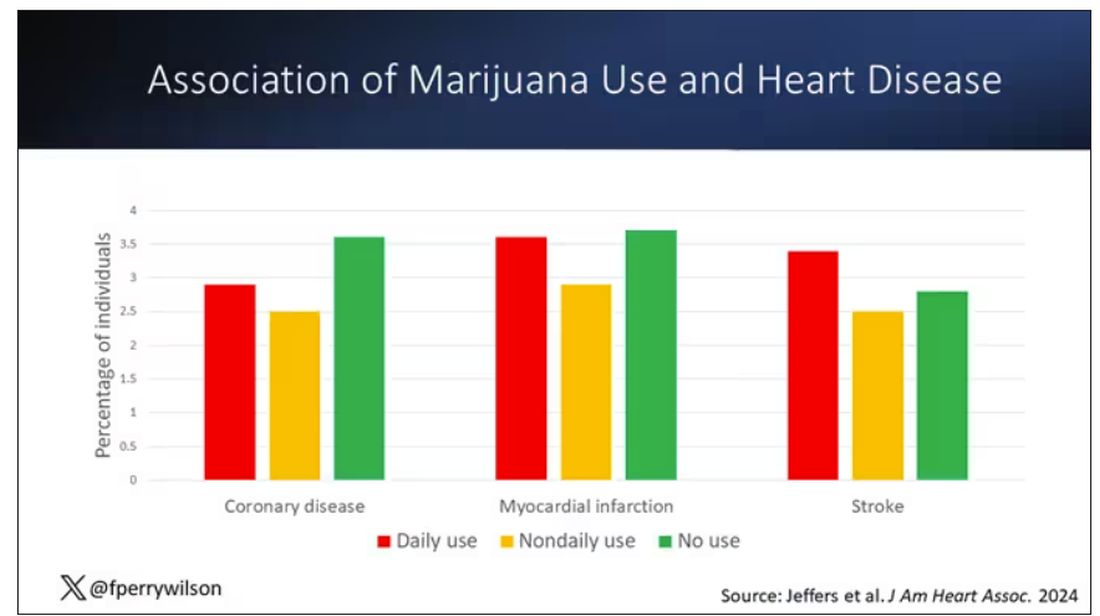

You can see the rates of the major cardiovascular outcomes here, stratified by daily use of marijuana, nondaily use, and no use. Broadly speaking, the risk was highest for daily users, lowest for occasional users, and in the middle for non-users.

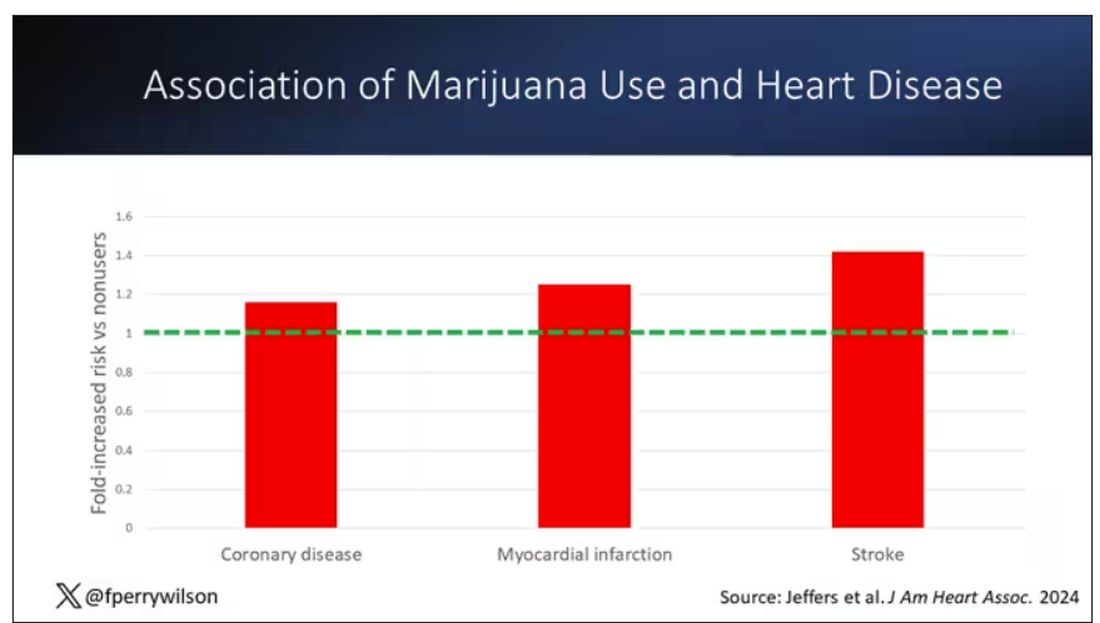

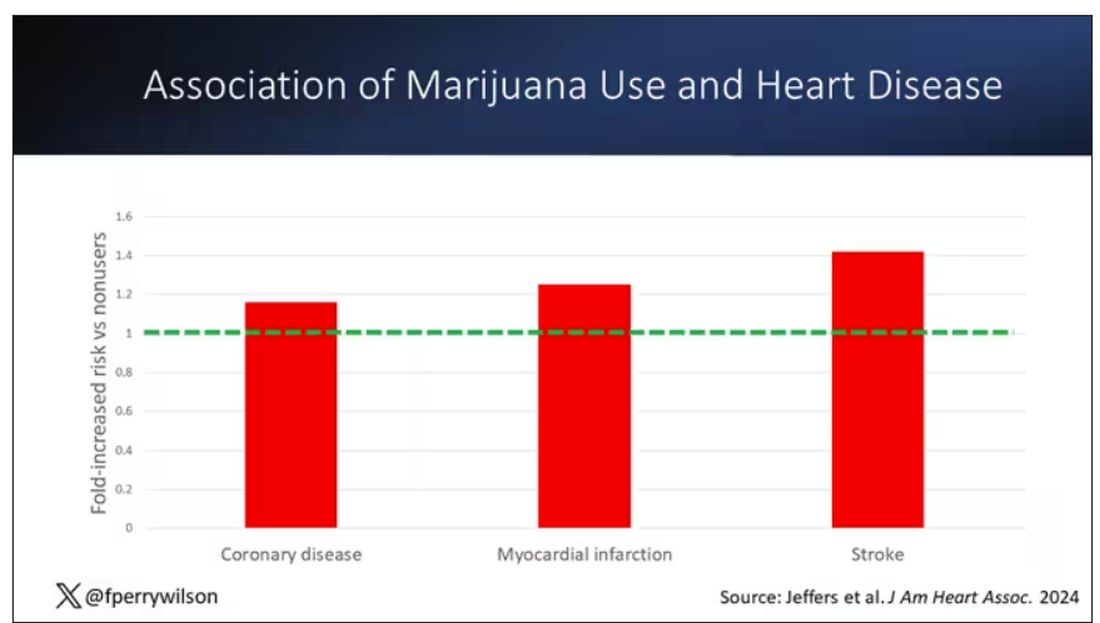

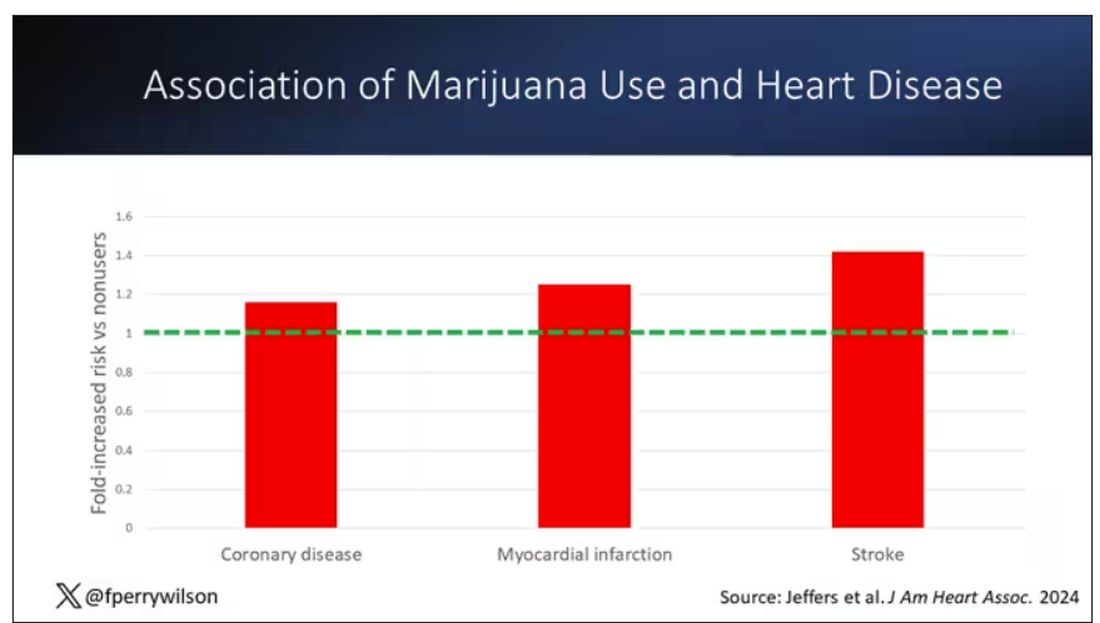

Of course, non-users and users are different in lots of other ways; non-users were quite a bit older, for example. Adjusting for all those factors showed that, independent of age, smoking status, the presence of diabetes, and so on, there was an independently increased risk for cardiovascular outcomes in people who used marijuana.

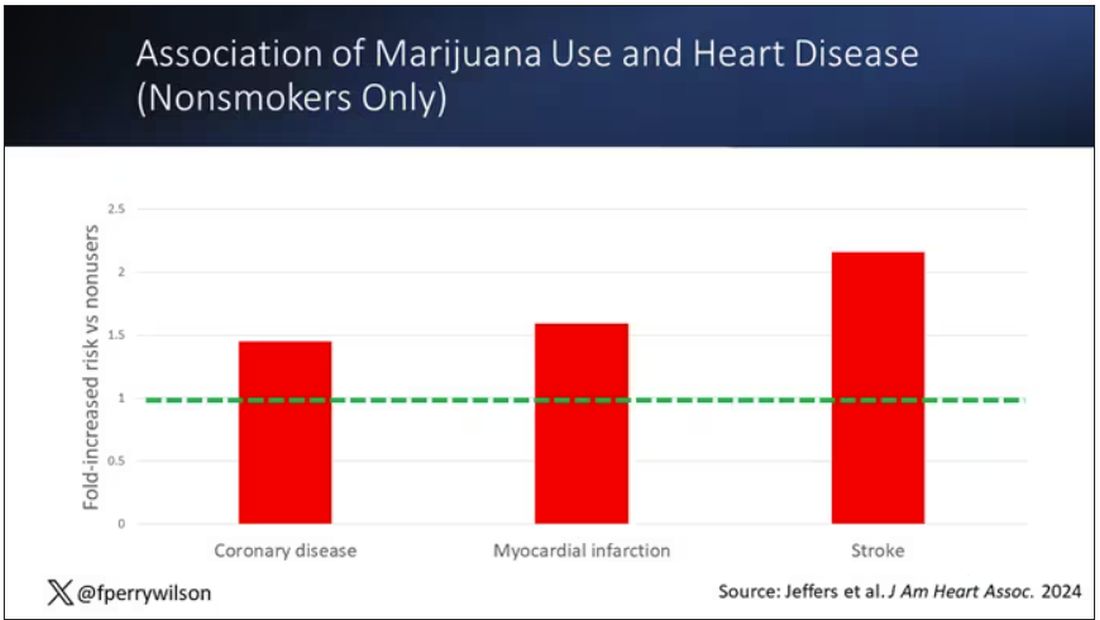

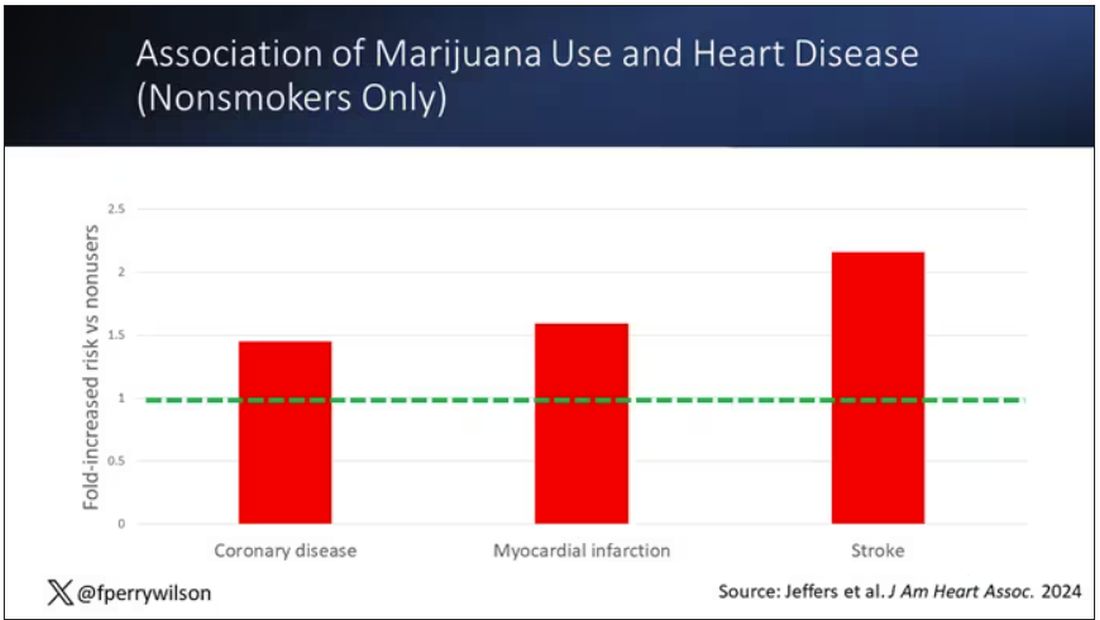

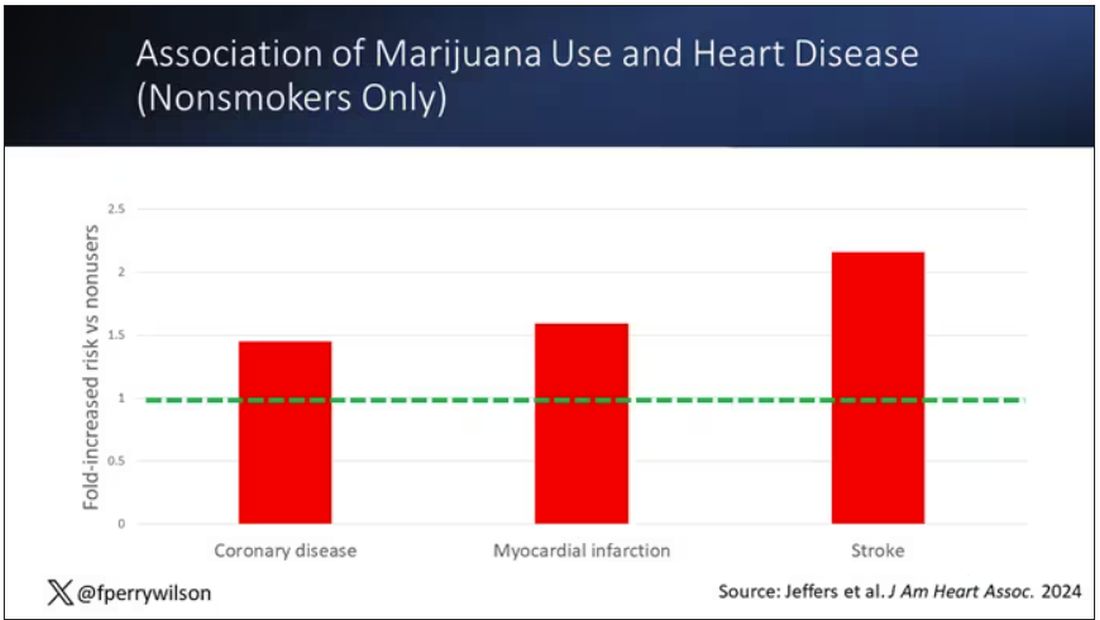

Importantly, 60% of people in this study were never smokers, and the results in that group looked pretty similar to the results overall.

But I said there were a couple of problems, so let’s dig into those a bit.

First, like most survey studies, this one requires honest and accurate reporting from its subjects. There was no verification of heart disease using electronic health records or of marijuana usage based on biosamples. Broadly, miscategorization of exposure and outcomes in surveys tends to bias the results toward the null hypothesis, toward concluding that there is no link between exposure and outcome, so perhaps this is okay.

The bigger problem is the fact that this is a cross-sectional design. If you really wanted to know whether marijuana led to heart disease, you’d do a longitudinal study following users and non-users for some number of decades and see who developed heart disease and who didn’t. (For the pedants out there, I suppose you’d actually want to randomize people to use marijuana or not and then see who had a heart attack, but the IRB keeps rejecting my protocol when I submit it.)

Here, though, we literally can’t tell whether people who use marijuana have more heart attacks or whether people who have heart attacks use more marijuana. The authors argue that there are no data that show that people are more likely to use marijuana after a heart attack or stroke, but at the time the survey was conducted, they had already had their heart attack or stroke.

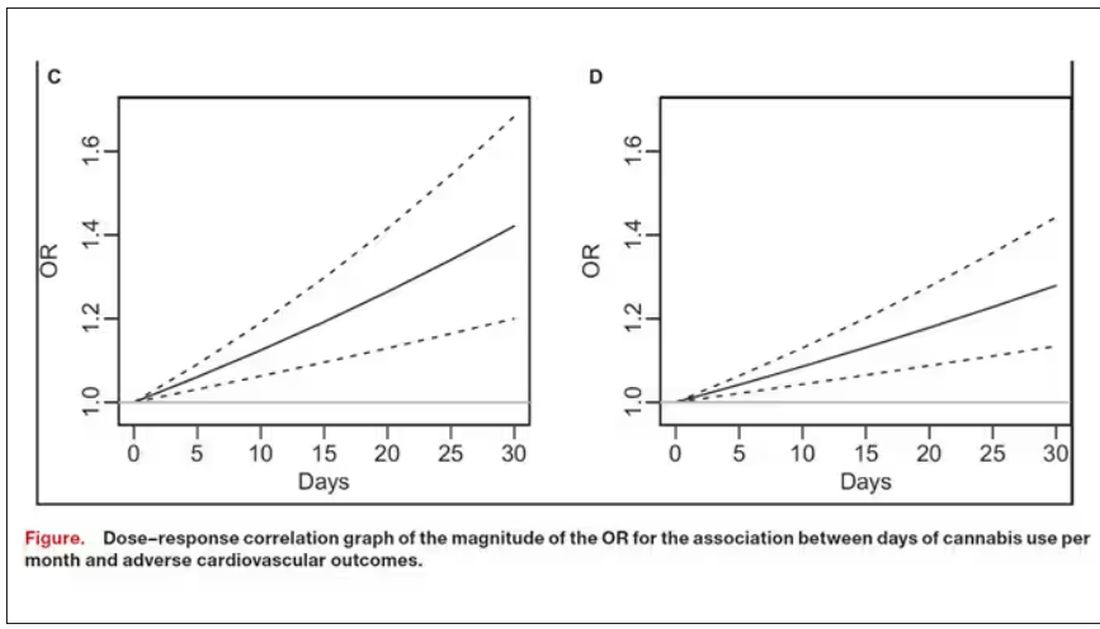

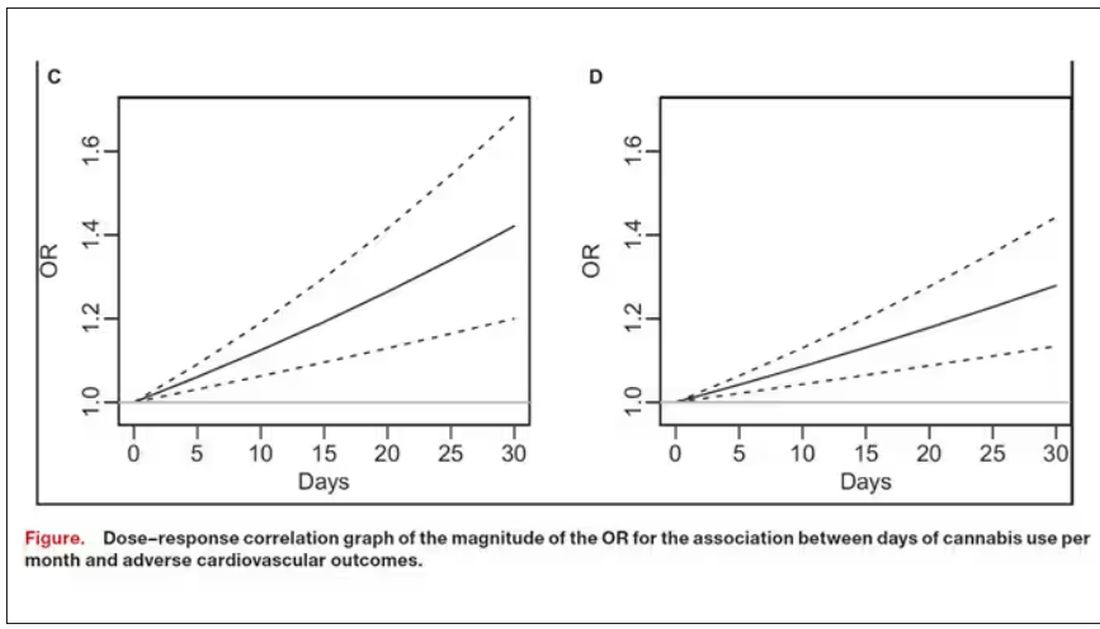

The authors also imply that they found a dose-response relationship between marijuana use and these cardiovascular outcomes. This is an important statement because dose response is one factor that we use to determine whether a risk factor may actually be causative as opposed to just correlative.

But I take issue with the dose-response language here. The model used to make these graphs classifies marijuana use as a single continuous variable ranging from 0 (no days of use in the past 30 days) to 1 (30 days of use in the past 30 days). The model is thus constrained to monotonically increase or decrease with respect to the outcome. To prove a dose response, you have to give the model the option to find something that isn’t a dose response — for example, by classifying marijuana use into discrete, independent categories rather than a single continuous number.

Am I arguing here that marijuana use is good for you? Of course not. Nor am I even arguing that it has no effect on the cardiovascular system. There are endocannabinoid receptors all over your vasculature. But a cross-sectional survey study, while a good start, is not quite the right way to answer the question. So, while the jury is still out, it’s high time for more research.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re an epidemiologist trying to explore whether some exposure is a risk factor for a disease, you can run into a tough problem when your exposure of interest is highly correlated with another risk factor for the disease. For decades, this stymied investigations into the link, if any, between marijuana use and cardiovascular disease because, for decades, most people who used marijuana in some way also smoked cigarettes — which is a very clear risk factor for heart disease.

But the times they are a-changing.

Thanks to the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in many states, and even broader social trends, there is now a large population of people who use marijuana but do not use cigarettes. That means we can start to determine whether marijuana use is an independent risk factor for heart disease.

And this week, we have the largest study yet to attempt to answer that question, though, as I’ll explain momentarily, the smoke hasn’t entirely cleared yet.

The centerpiece of the study we are discussing this week, “Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults,” which appeared in the Journal of the American Heart Association, is the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1984 that gathers data on all sorts of stuff that we do to ourselves: our drinking habits, our smoking habits, and, more recently, our marijuana habits.

The paper combines annual data from 2016 to 2020 representing 27 states and two US territories for a total sample size of more than 430,000 individuals. The key exposure? Marijuana use, which was coded as the number of days of marijuana use in the past 30 days. The key outcome? Coronary heart disease, collected through questions such as “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had a heart attack?”

Right away you might detect a couple of problems here. But let me show you the results before we worry about what they mean.

You can see the rates of the major cardiovascular outcomes here, stratified by daily use of marijuana, nondaily use, and no use. Broadly speaking, the risk was highest for daily users, lowest for occasional users, and in the middle for non-users.

Of course, non-users and users are different in lots of other ways; non-users were quite a bit older, for example. Adjusting for all those factors showed that, independent of age, smoking status, the presence of diabetes, and so on, there was an independently increased risk for cardiovascular outcomes in people who used marijuana.

Importantly, 60% of people in this study were never smokers, and the results in that group looked pretty similar to the results overall.

But I said there were a couple of problems, so let’s dig into those a bit.

First, like most survey studies, this one requires honest and accurate reporting from its subjects. There was no verification of heart disease using electronic health records or of marijuana usage based on biosamples. Broadly, miscategorization of exposure and outcomes in surveys tends to bias the results toward the null hypothesis, toward concluding that there is no link between exposure and outcome, so perhaps this is okay.

The bigger problem is the fact that this is a cross-sectional design. If you really wanted to know whether marijuana led to heart disease, you’d do a longitudinal study following users and non-users for some number of decades and see who developed heart disease and who didn’t. (For the pedants out there, I suppose you’d actually want to randomize people to use marijuana or not and then see who had a heart attack, but the IRB keeps rejecting my protocol when I submit it.)

Here, though, we literally can’t tell whether people who use marijuana have more heart attacks or whether people who have heart attacks use more marijuana. The authors argue that there are no data that show that people are more likely to use marijuana after a heart attack or stroke, but at the time the survey was conducted, they had already had their heart attack or stroke.

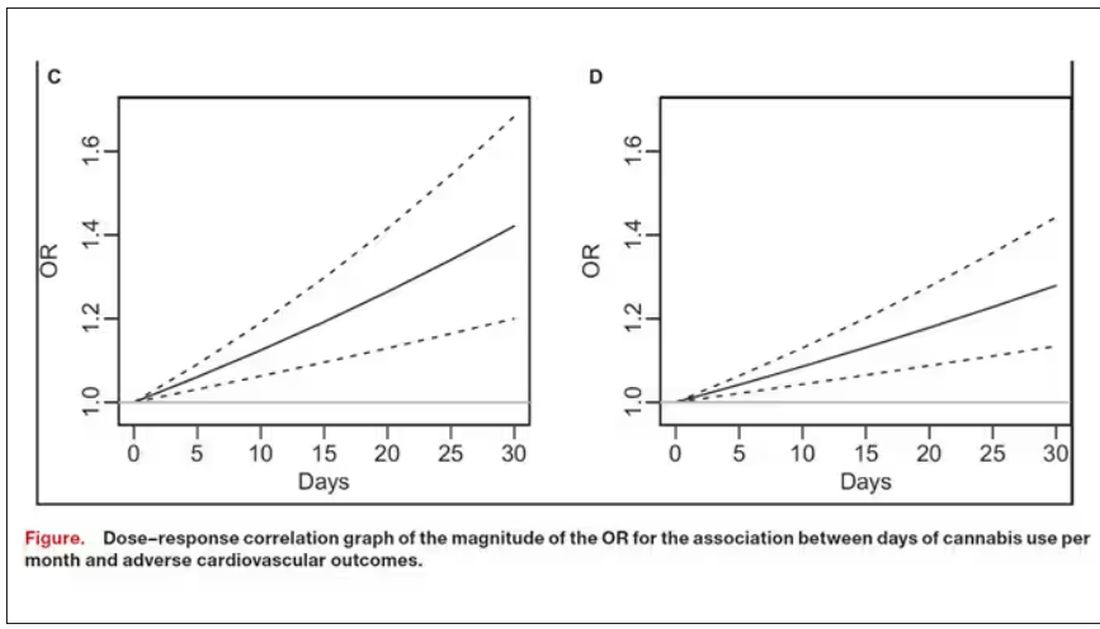

The authors also imply that they found a dose-response relationship between marijuana use and these cardiovascular outcomes. This is an important statement because dose response is one factor that we use to determine whether a risk factor may actually be causative as opposed to just correlative.

But I take issue with the dose-response language here. The model used to make these graphs classifies marijuana use as a single continuous variable ranging from 0 (no days of use in the past 30 days) to 1 (30 days of use in the past 30 days). The model is thus constrained to monotonically increase or decrease with respect to the outcome. To prove a dose response, you have to give the model the option to find something that isn’t a dose response — for example, by classifying marijuana use into discrete, independent categories rather than a single continuous number.

Am I arguing here that marijuana use is good for you? Of course not. Nor am I even arguing that it has no effect on the cardiovascular system. There are endocannabinoid receptors all over your vasculature. But a cross-sectional survey study, while a good start, is not quite the right way to answer the question. So, while the jury is still out, it’s high time for more research.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re an epidemiologist trying to explore whether some exposure is a risk factor for a disease, you can run into a tough problem when your exposure of interest is highly correlated with another risk factor for the disease. For decades, this stymied investigations into the link, if any, between marijuana use and cardiovascular disease because, for decades, most people who used marijuana in some way also smoked cigarettes — which is a very clear risk factor for heart disease.

But the times they are a-changing.

Thanks to the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in many states, and even broader social trends, there is now a large population of people who use marijuana but do not use cigarettes. That means we can start to determine whether marijuana use is an independent risk factor for heart disease.

And this week, we have the largest study yet to attempt to answer that question, though, as I’ll explain momentarily, the smoke hasn’t entirely cleared yet.

The centerpiece of the study we are discussing this week, “Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults,” which appeared in the Journal of the American Heart Association, is the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1984 that gathers data on all sorts of stuff that we do to ourselves: our drinking habits, our smoking habits, and, more recently, our marijuana habits.

The paper combines annual data from 2016 to 2020 representing 27 states and two US territories for a total sample size of more than 430,000 individuals. The key exposure? Marijuana use, which was coded as the number of days of marijuana use in the past 30 days. The key outcome? Coronary heart disease, collected through questions such as “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had a heart attack?”

Right away you might detect a couple of problems here. But let me show you the results before we worry about what they mean.

You can see the rates of the major cardiovascular outcomes here, stratified by daily use of marijuana, nondaily use, and no use. Broadly speaking, the risk was highest for daily users, lowest for occasional users, and in the middle for non-users.

Of course, non-users and users are different in lots of other ways; non-users were quite a bit older, for example. Adjusting for all those factors showed that, independent of age, smoking status, the presence of diabetes, and so on, there was an independently increased risk for cardiovascular outcomes in people who used marijuana.

Importantly, 60% of people in this study were never smokers, and the results in that group looked pretty similar to the results overall.

But I said there were a couple of problems, so let’s dig into those a bit.

First, like most survey studies, this one requires honest and accurate reporting from its subjects. There was no verification of heart disease using electronic health records or of marijuana usage based on biosamples. Broadly, miscategorization of exposure and outcomes in surveys tends to bias the results toward the null hypothesis, toward concluding that there is no link between exposure and outcome, so perhaps this is okay.

The bigger problem is the fact that this is a cross-sectional design. If you really wanted to know whether marijuana led to heart disease, you’d do a longitudinal study following users and non-users for some number of decades and see who developed heart disease and who didn’t. (For the pedants out there, I suppose you’d actually want to randomize people to use marijuana or not and then see who had a heart attack, but the IRB keeps rejecting my protocol when I submit it.)

Here, though, we literally can’t tell whether people who use marijuana have more heart attacks or whether people who have heart attacks use more marijuana. The authors argue that there are no data that show that people are more likely to use marijuana after a heart attack or stroke, but at the time the survey was conducted, they had already had their heart attack or stroke.

The authors also imply that they found a dose-response relationship between marijuana use and these cardiovascular outcomes. This is an important statement because dose response is one factor that we use to determine whether a risk factor may actually be causative as opposed to just correlative.

But I take issue with the dose-response language here. The model used to make these graphs classifies marijuana use as a single continuous variable ranging from 0 (no days of use in the past 30 days) to 1 (30 days of use in the past 30 days). The model is thus constrained to monotonically increase or decrease with respect to the outcome. To prove a dose response, you have to give the model the option to find something that isn’t a dose response — for example, by classifying marijuana use into discrete, independent categories rather than a single continuous number.

Am I arguing here that marijuana use is good for you? Of course not. Nor am I even arguing that it has no effect on the cardiovascular system. There are endocannabinoid receptors all over your vasculature. But a cross-sectional survey study, while a good start, is not quite the right way to answer the question. So, while the jury is still out, it’s high time for more research.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.