User login

CASE

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital from home with acute onset, unrelenting, upper abdominal pain radiating to the back and nausea/vomiting. Her medical history includes bile duct obstruction secondary to gall stones, which was managed in another facility 6 days earlier with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and stenting. The patient has type 2 diabetes (managed with metformin and glargine insulin), hypertension (managed with lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide), and cholesterolemia (managed with atorvastatin).

On admission, the patient's white blood cell count is 14.7 x 103 cells/mm3, heart rate is 100 bpm, blood pressure is 90/68 mm Hg, and temperature is 101.5° F. Serum amylase and lipase are 3 and 2 times the upper limit of normal, respectively. A working diagnosis of acute pancreatitis with sepsis is made. Blood cultures are drawn. A computed tomography scan confirms acute pancreatitis. She receives one dose of meropenem, is started on intravenous fluids and morphine, and is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management.

Her ICU course is complicated by worsening sepsis despite aggressive fluid resuscitation, nutrition, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. On post-admission Day 2, blood culture results reveal Escherichia coli that is resistant to gentamicin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, ceftriaxone, piperacillin/tazobactam, imipenem, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline. Additional susceptibility testing is ordered.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conservatively estimates that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are responsible for 2 billion infections annually, resulting in approximately 23,000 deaths and $20 billion in excess health care expenditures annually.1 Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria typically require longer hospitalizations, more expensive drug therapies, and additional follow-up visits.1 They also result in greater morbidity and mortality compared with similar infections involving non-resistant bacteria.1 To compound the problem, antibiotic development has steadily declined over the last 3 decades, with few novel antimicrobials developed in recent years.2 The most recently approved antibiotics with new mechanisms of action were linezolid in 2000 and daptomycin in 2003, preceded by the carbapenems 15 years earlier. (See “New antimicrobials in the pipeline.”)

New antimicrobials in the pipeline

The Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act was signed into law in 2012, creating a new designation—qualified infectious diseases products (QIDPs)—for antibiotics in development for serious or life-threatening infections (https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ144/PLAW-112publ144.pdf). QIDPs are granted expedited FDA approval and an additional 5 years of patent exclusivity in order to encourage new antimicrobial development.

Five antibiotics have been approved with the QIDP designation: tedizolid, dalbavancin, oritavancin, ceftolozane/tazobactam, and ceftazidime/avibactam, and 20 more agents are in development including a new fluoroquinolone, delafloxacin, for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections including those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and a new tetracycline, eravacycline, for complicated intra-abdominal infections and complicated UTIs. Eravacycline has in vitro activity against penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, MRSA, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, and multidrug-resistant A. baumannii. Both drugs will be available in intravenous and oral formulations.

Greater efforts aimed at using antimicrobials sparingly and appropriately, as well as developing new antimicrobials with activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens, are ultimately needed to address the threat of antimicrobial resistance. This article describes the evidence-based management of inpatient infections caused by resistant bacteria and the role family physicians (FPs) can play in reducing further development of resistance through antimicrobial stewardship practices.

Health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

S. aureus is a common culprit of hospital-acquired infections, including central line-associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and nosocomial skin and soft tissue infections. In fact, nearly half of all isolates from these infections are reported to be methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).3

Patients at greatest risk for MRSA infections include those who have been recently hospitalized, those receiving recent antibiotic therapy or surgery, long-term care residents, intravenous drug abusers, immunocompromised patients, hemodialysis patients, military personnel, and athletes who play contact sports.4,5 Patients with these infections often require the use of an anti-MRSA agent (eg, vancomycin, linezolid) in empiric antibiotic regimens.6,7 The focus of this discussion is on MRSA in hospital and long-term care settings; a discussion of community-acquired MRSA is addressed elsewhere. (See “Antibiotic stewardship: The FP’s role,” J Fam Pract. 2016;65:876-885.8)

Efforts are working, but problems remain. MRSA accounts for almost 60% of S. aureus isolates in ICUs.9 Thankfully, rates of health care-associated MRSA are now either static or declining nationwide, as a result of major initiatives targeted toward preventing health care-associated infection in recent years.10

Methicillin resistance in S. aureus results from expression of PBP2a, an altered penicillin-binding protein with reduced binding affinity for beta-lactam antibiotics. As a result, MRSA isolates are resistant to most beta-lactams.9 Resistance to macrolides, azithromycin, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin is also common in health care-associated MRSA.9

The first case of true vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) in the United States was reported in 2002.11 Fortunately, both VRSA and vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) have remained rare throughout the United States and abroad.9,11 Heterogeneous VISA (hVISA), which is characterized by a few resistant subpopulations within a fully susceptible population of S. aureus, is more common than VRSA or VISA. Unfortunately, hVISA is difficult to detect using commercially available susceptibility tests. This can result in treatment failure with vancomycin, even though the MRSA isolate may appear fully susceptible and the patient has received clinically appropriate doses of the drug.12

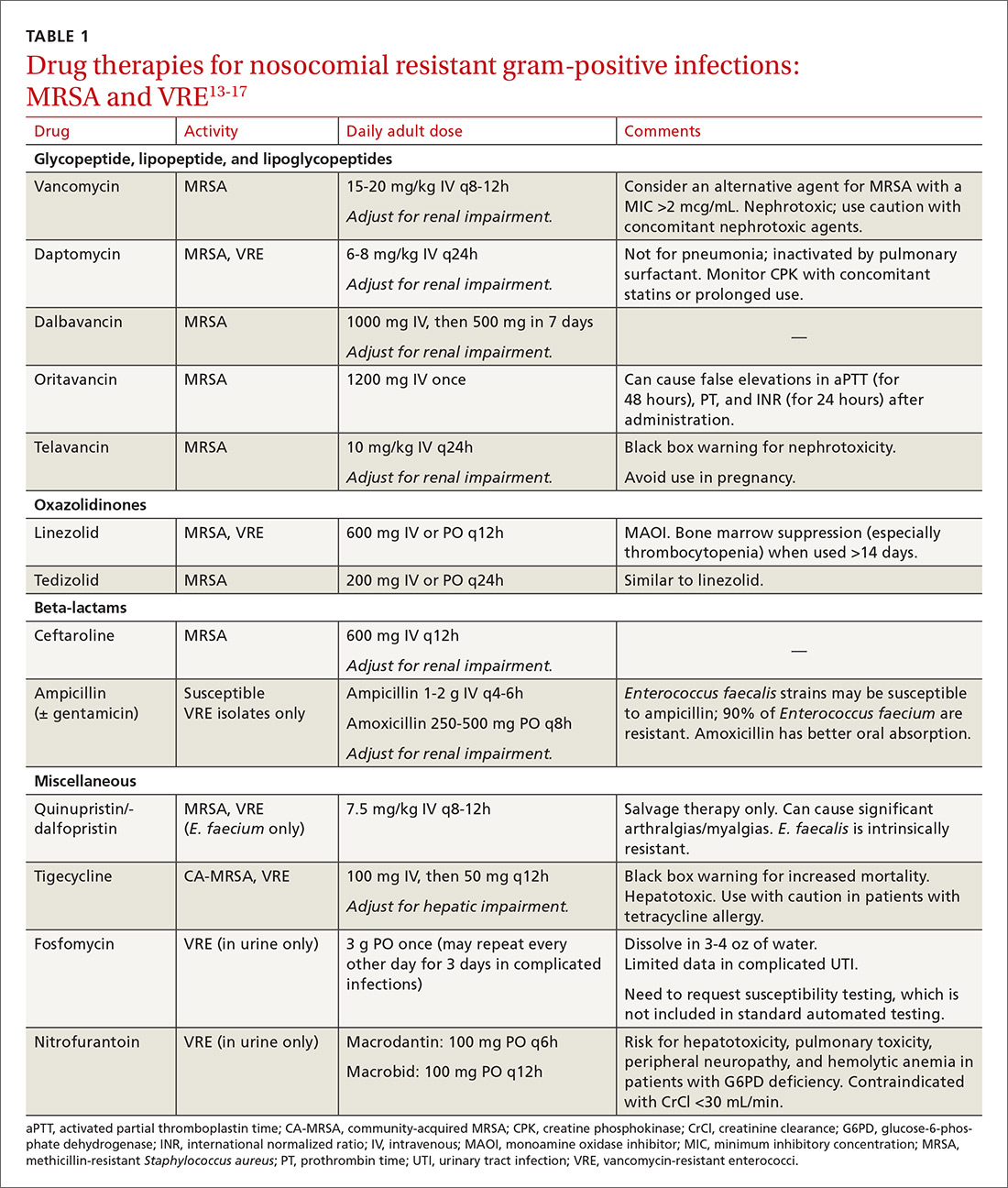

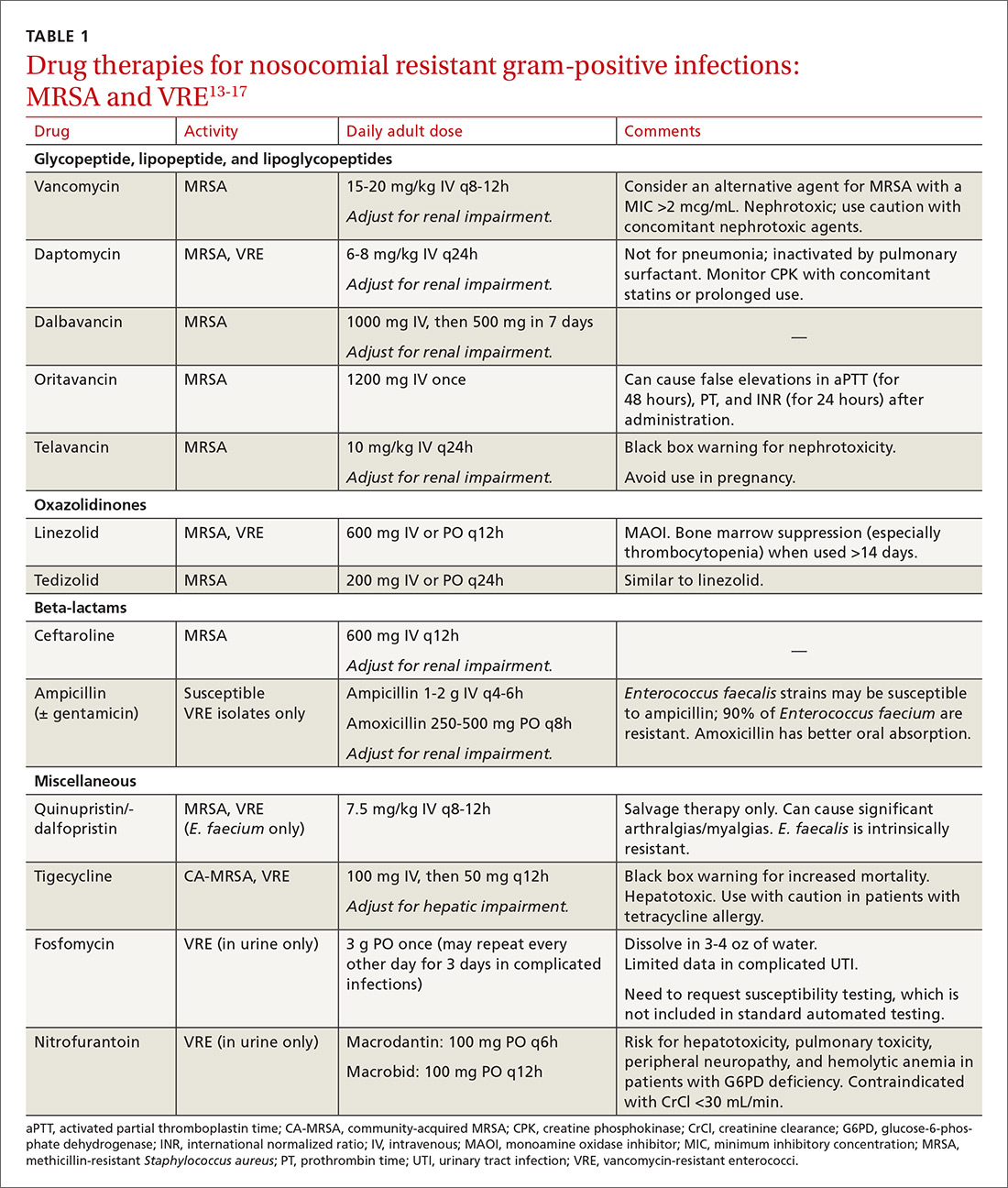

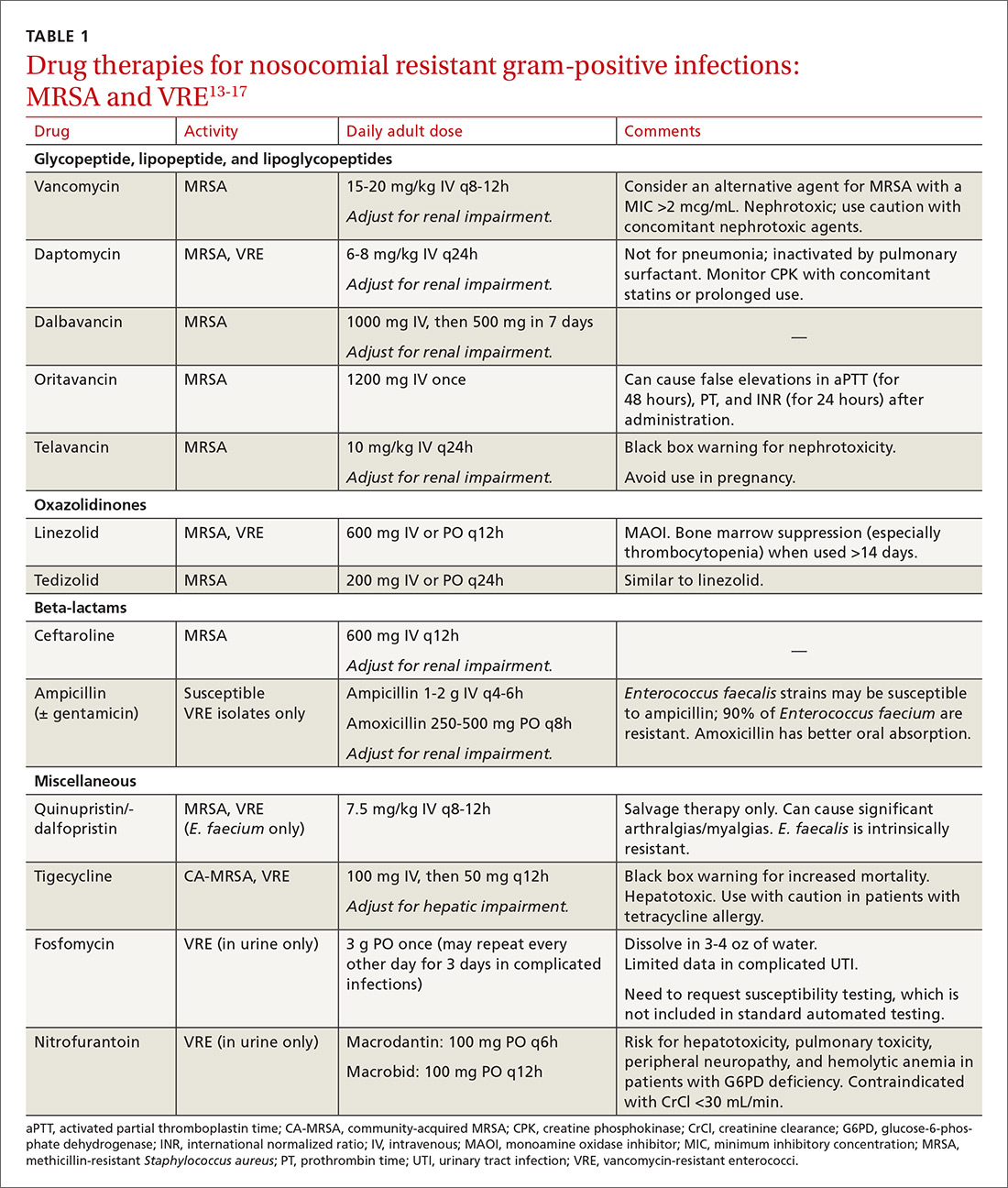

Treatment. Vancomycin is the mainstay of therapy for many systemic health care-associated MRSA infections. Alternative therapies (daptomycin or linezolid) should be considered for isolates with a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) >2 mcg/mL or in the setting of a poor clinical response.4 Combination therapy may be warranted in the setting of treatment failure. Because comparative efficacy data for alternative therapies is lacking, agent selection should be tailored to the site of infection and patient-specific factors such as allergies, drug interactions, and the risk for adverse events (TABLE 113-17).

Ceftaroline, the only beta-lactam with activity against MRSA, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSIs) and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia.18 Tedizolid, a new oxazolidinone similar to linezolid, as well as oritavancin and dalbavancin—2 long-acting glycopeptides—were also recently approved for use with ABSSIs.13,14,19

Oritavancin and dalbavancin both have dosing regimens that may allow for earlier hospital discharge or treatment in an outpatient setting.13,14 Telavancin, quinupristin/dalfopristin, and tigecycline are typically reserved for salvage therapy due to adverse event profiles and/or limited efficacy data.15

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE)

Enterococci are typically considered normal gastrointestinal tract flora. However, antibiotic exposure can alter gut flora allowing for VRE colonization, which in some instances, can progress to the development of a health care-associated infection.15 Therefore, it is important to distinguish whether a patient is colonized or infected with VRE because treatment of colonization is unnecessary and may lead to resistance and other adverse effects.15

Enterococci may be the culprit in nosocomially-acquired intra-abdominal infections, bacteremia, endocarditis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and skin and skin structure infections, and can exhibit resistance to ampicillin, aminoglycosides, and vancomycin.15 VRE is predominantly a health care-associated pathogen and may account for up to 77% of all health care-associated Enterococcus faecium infections and 9% of Enterococcus faecalis infections.1

Treatment. Antibiotic selection for VRE infections depends upon the site of infection, patient comorbidities, the potential for drug interactions, and treatment duration. Current treatment options include linezolid, daptomycin, quinupristin/dalfopristin (for E. faecium only), tigecycline, and ampicillin if the organism is susceptible (TABLE 113-17).15 For cystitis caused by VRE (not urinary colonization), fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin are additional options.16

Resistant Enterobacteriaceae

Resistant Enterobacteriaceae such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae have emerged as a result of increased broad-spectrum antibiotic utilization and have been implicated in health care-associated UTIs, intra-abdominal infections, bacteremia, and even pneumonia.1 Patients with prolonged hospital stays and invasive medical devices, such as urinary and vascular catheters, endotracheal tubes, and endoscopy scopes, have the highest risk for infection with these organisms.20

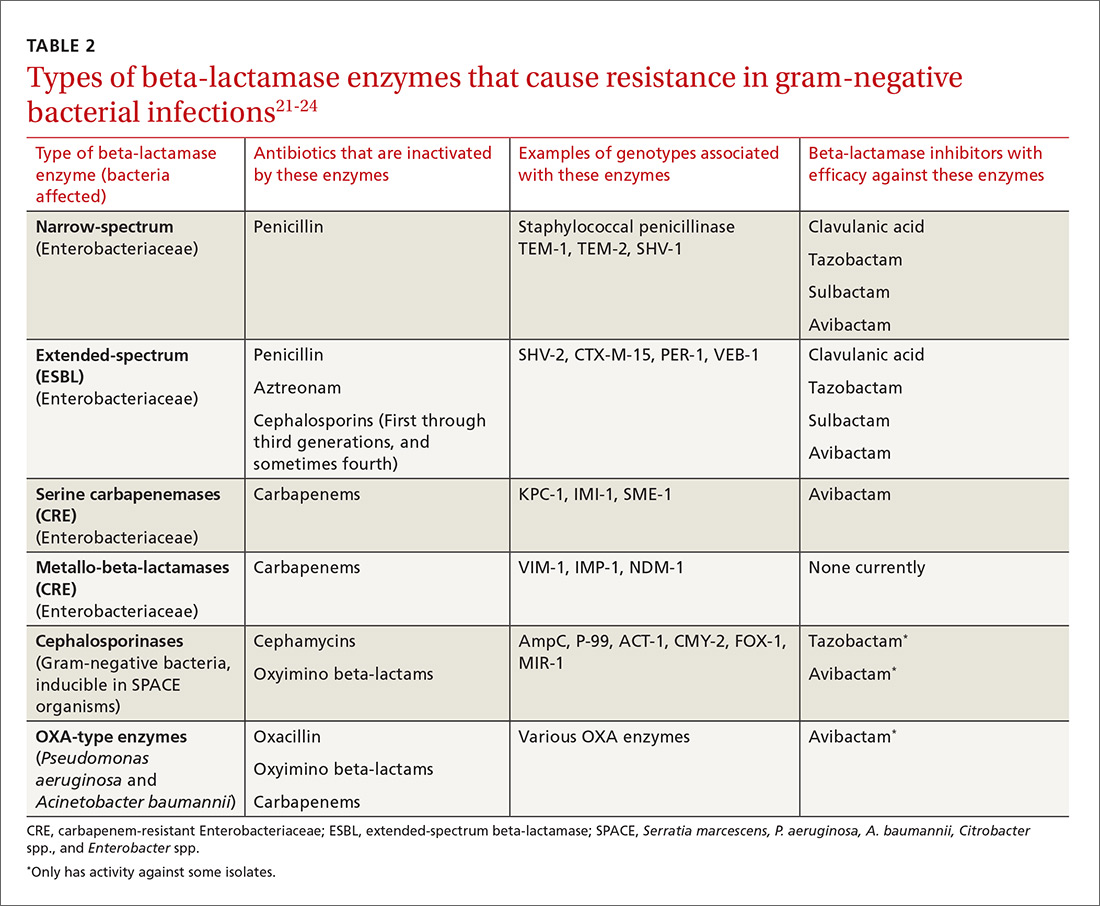

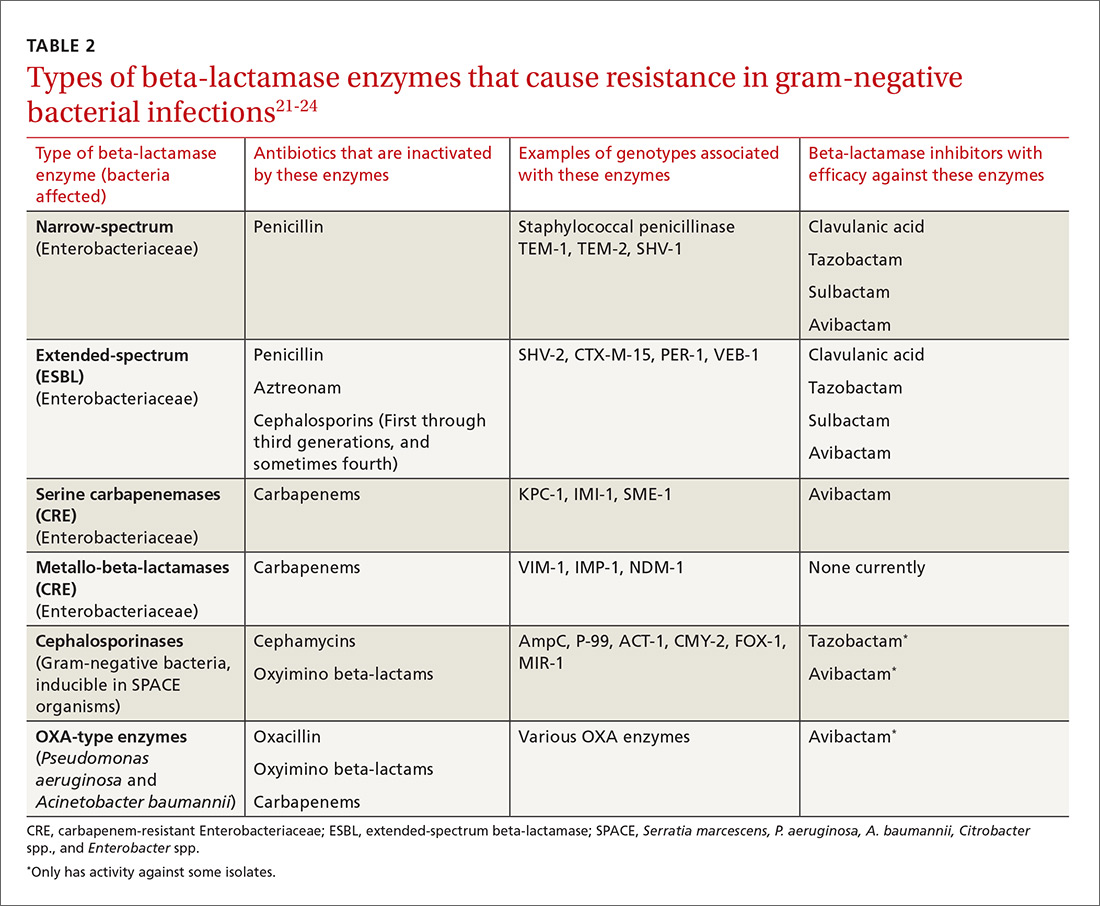

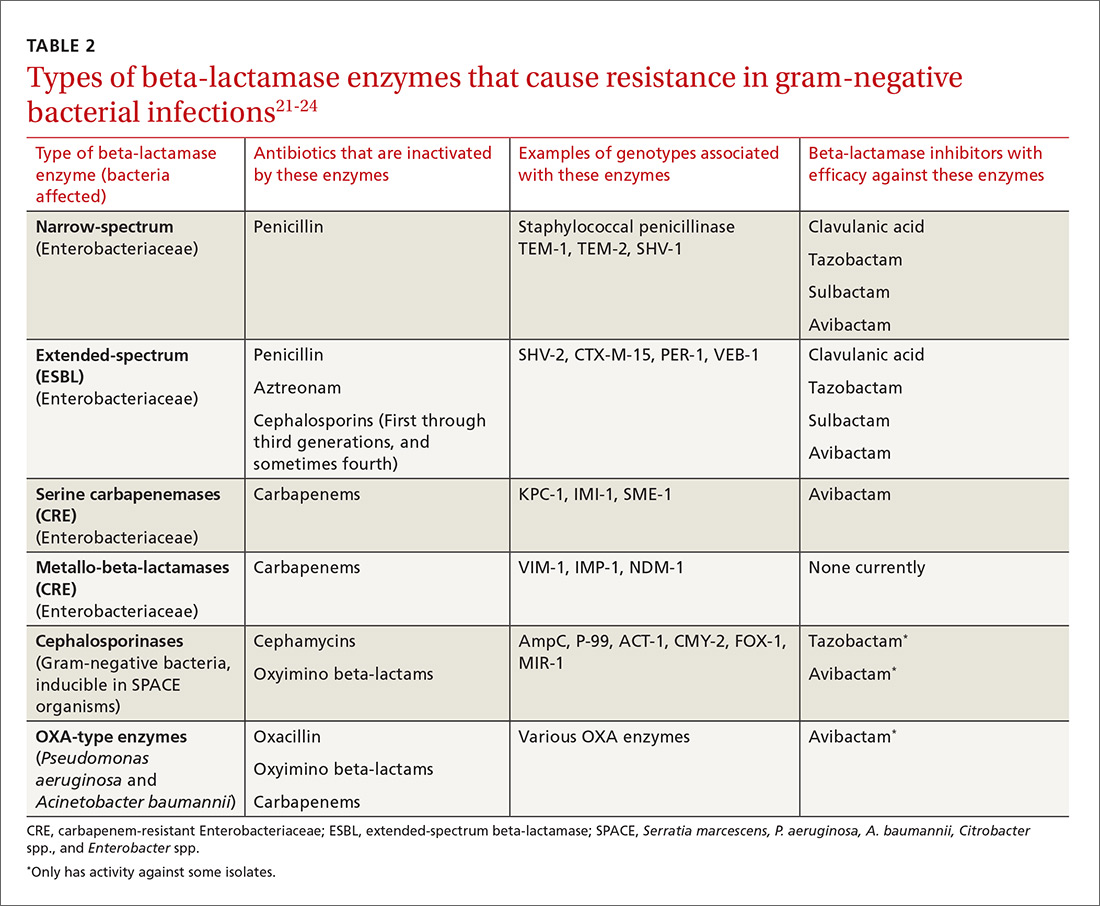

The genotypic profiles of resistance among the Enterobacteriaceae are diverse and complex, resulting in different levels of activity for the various beta-lactam agents (TABLE 221-24).25 Furthermore, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producers and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are often resistant to other classes of antibiotics, too, including aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones.20,25 The increasing diversity among beta-lactamase enzymes has made the selection of appropriate antibiotic therapy challenging, since the ability to identify specific beta-lactamase genes is not yet available in the clinical setting.

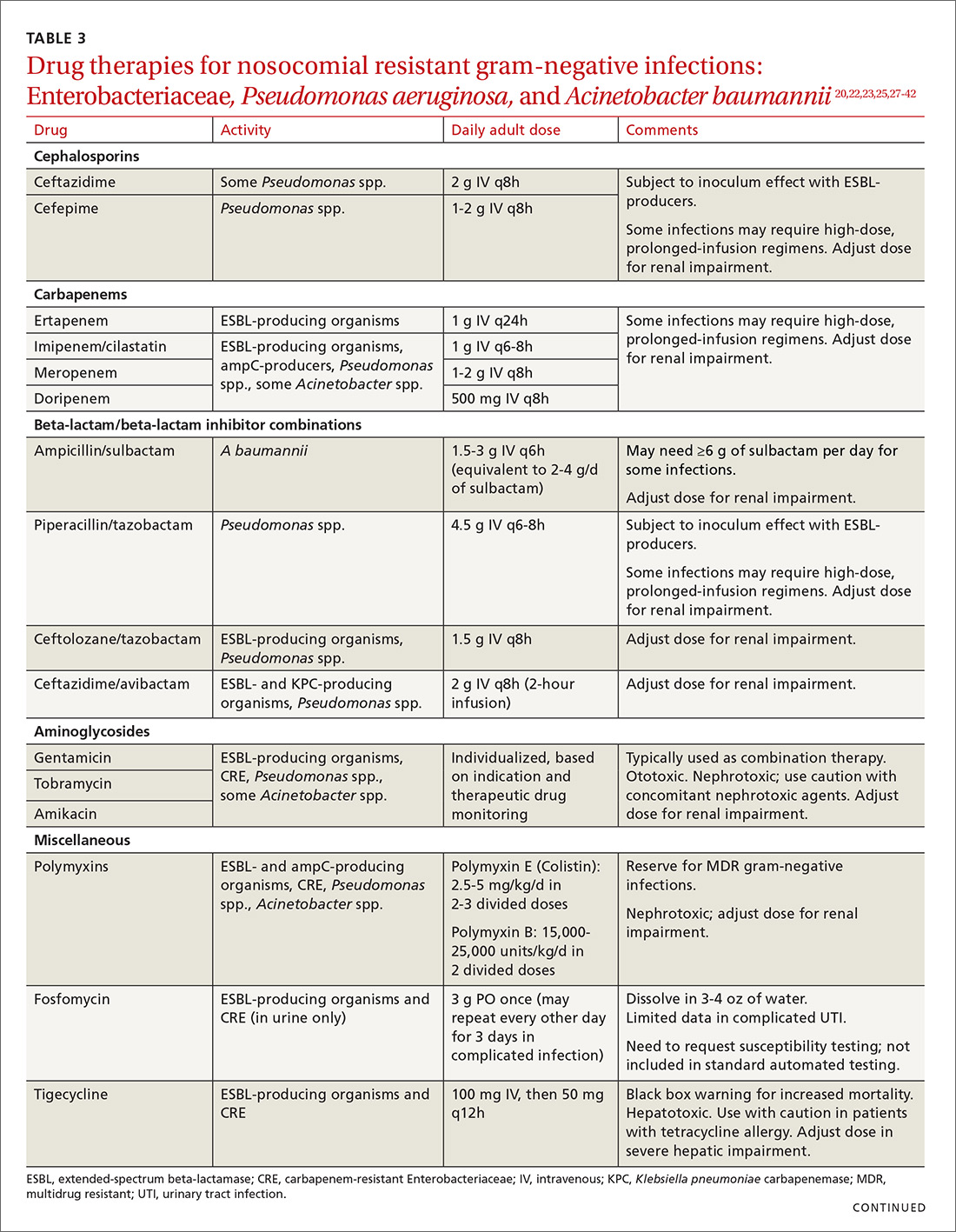

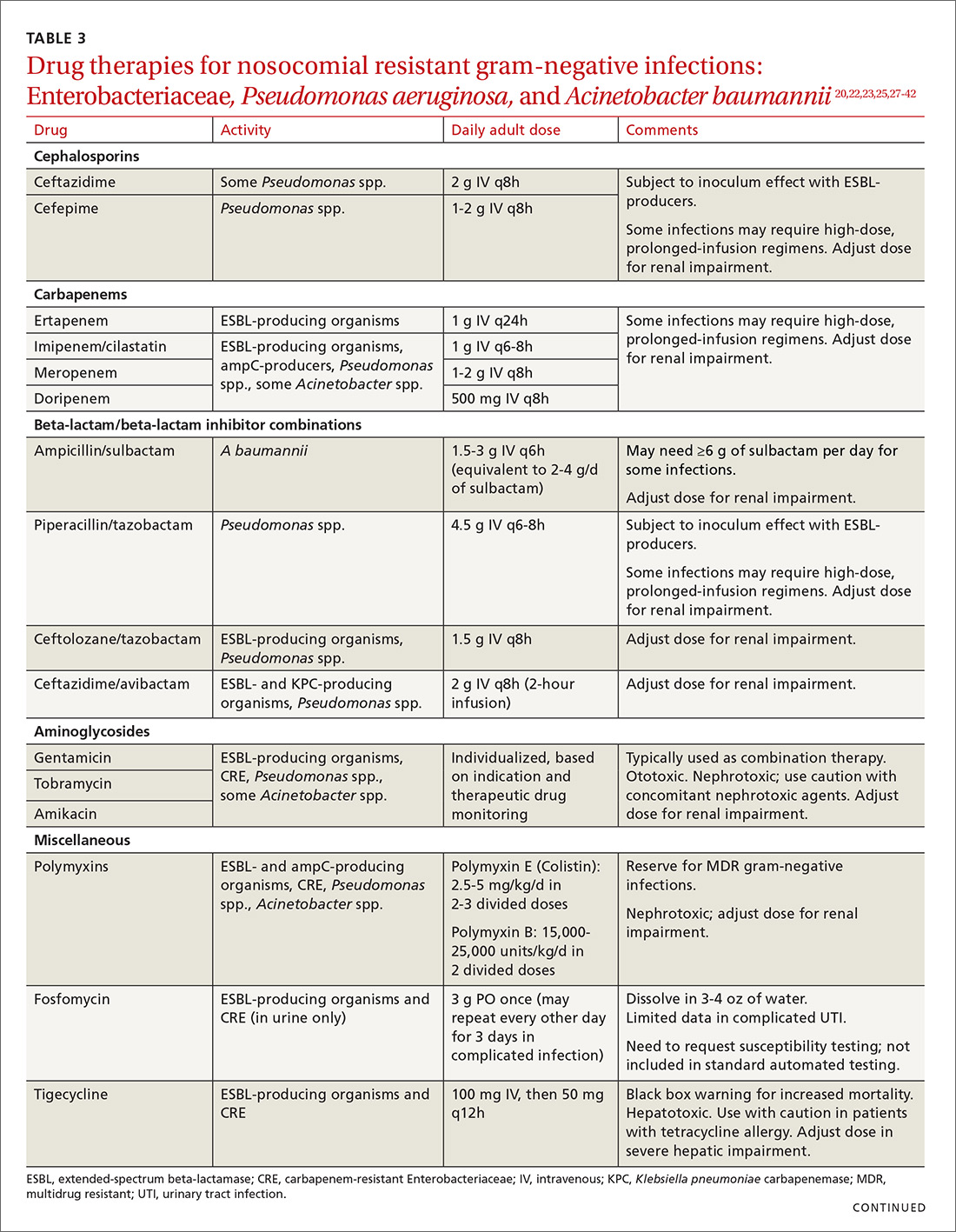

ESBLs emerged shortly after the widespread use of cephalosporins in practice and are resistant to a variety of beta-lactams (TABLE 221-24). Carbapenems are considered the mainstay of therapy for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.20,26 An alternative for urinary and biliary tract infections can be piperacillin-tazobactam,21,26 but the combination may be subject to the inoculum effect, in which MIC and risk for treatment failure increase in infections with a high bacterial burden (colony-forming units/mL) such as pneumonias (TABLE 320,22,,23,25,27-42).22

Cefepime may retain activity against some ESBL-producing isolates, but it is also susceptible to the inoculum effect and should only be used for non–life-threatening infections and at higher doses.23 Fosfomycin has activity against ESBL-producing bacteria, but is only approved for oral use in UTIs in the United States.20,27 Ceftolozane/tazobactam (Zerbaxa) and ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz) were approved in 2014 and 2015, respectively, by the FDA for the management of complicated urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections caused by susceptible ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. In order to preserve the antimicrobial efficacy of these 2 newer agents, however, they are typically reserved for definitive therapy when in vitro susceptibility is demonstrated and there are no other viable options.

AmpC beta-lactamases are resistant to similar agents as the ESBLs, in addition to cefoxitin and the beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations containing clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and in some cases, tazobactam. Resistance can be induced and emerges in certain pathogens while patients are on therapy.28 Fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides have a low risk of developing resistance while patients are on therapy, but are more likely to cause adverse effects and toxicity compared with the beta-lactams.28 Carbapenems have the lowest risk of emerging resistance and are the empiric treatment of choice for known AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in serious infections.20,28 Cefepime may also be an option in less severe infections, such as UTIs or those in which adequate source control has been achieved.28,29

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) have become a serious threat as a result of increased carbapenem use. While carbapenem resistance is less common in the United States than worldwide, rates have increased nearly 4-fold (1.2% to 4.2%) in the last decade, with some regions of the country experiencing substantially higher rates.24 The most commonly reported CRE genotypes identified in the United States include the serine carbapenemase (K. pneumoniae carbapenemase, or KPC), and the metallo-beta-lactamases (Verona integrin-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase, or VIM, and the New Dehli metallo-beta-lactamase, or NDM), with each class conferring slightly different resistance patterns (TABLE 221-24).20,30

Few treatment options exist for Enterobacteriaceae producing a serine carbapenemase, and, unfortunately, evidence to support these therapies is extremely limited. Some CRE isolates retain susceptibility to the polymyxins, the aminoglycosides, and tigecycline.30 Even fewer options exist for treating Enterobacteriaceae producing metallo-beta-lactamases, which are typically only susceptible to the polymyxins and tigecycline.43-45

Several studies have demonstrated lower mortality rates when combination therapy is utilized for CRE bloodstream infections.31,32 Furthermore, the combination of colistin, tigecycline, and meropenem was found to have a significant mortality advantage.32 Double carbapenem therapy has been effective in several cases of invasive KPC-producing K. pneumoniae infections.33,34 However, it is important to note that current clinical evidence comes from small, single-center, retrospective studies, and additional research is needed to determine optimal combinations and dosing strategies for these infections.

Lastly, ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz) was recently approved for the treatment of complicated urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections, and has activity against KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae, but not those producing metallo-beta-lactamases, like VIM or NDM. In the absence of strong evidence to support one therapy over another, it may be reasonable to select at least 2 active agents when treating serious CRE infections. Agent selection should be based on the site of the infection, susceptibility data, and patient-specific factors (TABLE 320,22,,23,25,27-42). The CDC also recommends contact precautions for patients who are colonized or infected with CRE.35

Multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative rod that can be isolated from nosocomial infections such as UTIs, bacteremias, pneumonias, skin and skin structure infections, and burn infections.20 Pseudomonal infections are associated with high morbidity and mortality and can cause recurrent infections in patients with cystic fibrosis.20 Multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa (MDR-P) infections account for approximately 13% of all health care-associated pseudomonal infections nationally.1 Both fluoroquinolone and aminoglycoside resistance has emerged, and multiple types of beta-lactamases (ESBL, AmpC, carbapenemases) have resulted in organisms that are resistant to nearly all anti-pseudomonal beta-lactams.20

Treatment. For patients at risk for MDR-P, some clinical practice guidelines have recommended using an empiric therapy regimen that contains antimicrobial agents from 2 different classes with activity against P. aeruginosa to increase the likelihood of susceptibility to at least one agent.6 De-escalation can occur once culture and susceptibility results are available.6 Dose optimization based on pharmacodynamic principles is critical for ensuring clinical efficacy and minimizing resistance.36 The use of high-dose, prolonged-infusion beta-lactams (piperacillin/tazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, and carbapenems) is becoming common practice at institutions with higher rates of resistance.36-38

A resurgence of polymyxin (colistin) use for MDR-P isolates has occurred, and may be warranted empirically in select patients, based on local resistance patterns and patient history. Newer pharmacokinetic data are available, resulting in improved dosing strategies that may enhance efficacy while alleviating some of the nephrotoxicity concerns associated with colistin therapy.39

Ceftolozane/tazobactam (Zerbaxa) and ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz) are options for complicated urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections caused by susceptible P. aeruginosa isolates. Given the lack of comparative efficacy data available for the management of MDR-P infections, agent selection should be based on site of infection, susceptibility data, and patient-specific factors.

Multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

A. baumannii is a lactose-fermenting, gram-negative rod sometimes implicated in nosocomial pneumonias, line-related bloodstream infections, UTIs, and surgical site infections.20 Resistance has been documented for nearly all classes of antibiotics, including carbapenems.1,20 Over half of all health care-associated A. baumannii isolates in the United States are multidrug resistant.1

Treatment. Therapy options for A. baumannii infections are often limited to polymyxins, tigecycline, carbapenems (except ertapenem), aminoglycosides, and high-dose ampicillin/sulbactam, depending on in vitro susceptibilities.40,41 When using ampicillin/sulbactam for A. baumannii infections, sulbactam is the active ingredient. Doses of 2 to 4 g/d of sulbactam have demonstrated efficacy in non-critically ill patients, while critically ill patients may require higher doses (up to 12 g/d).40 Colistin is considered the mainstay of therapy for carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii. It should be used in combination with either a carbapenem, rifampin, an aminoglycoside, or tigecycline.42

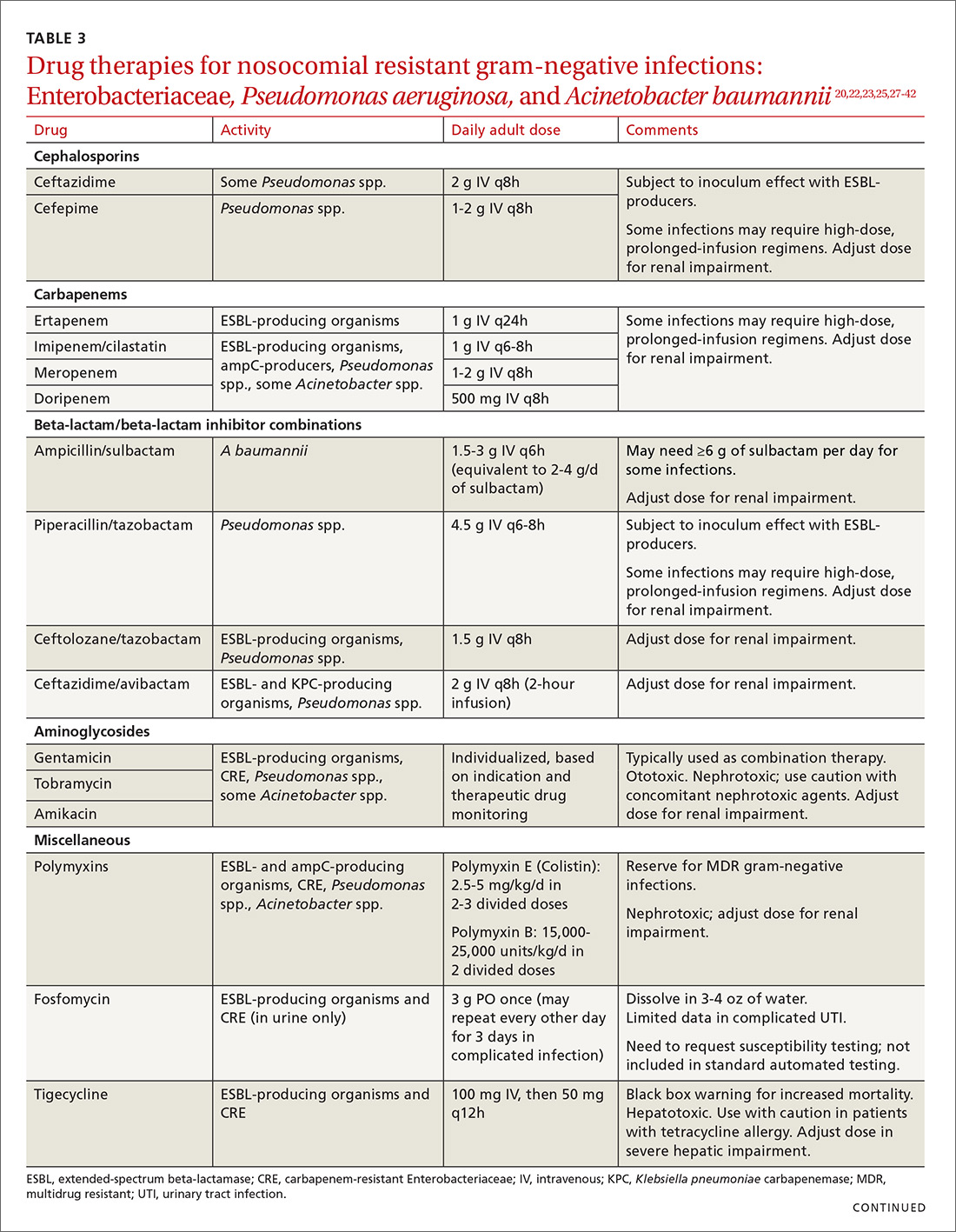

Drug therapies for nosocomial-resistant gram-negative infections, along with clinical pearls for use, are summarized in TABLE 3.20,22,23,25,27-42 Because efficacy data are limited for treating infections caused by these pathogens, appropriate antimicrobial selection is frequently guided by location of infection, susceptibility patterns, and patient-specific factors such as allergies and the risk for adverse effects.

Antimicrobial stewardship

Antibiotic misuse has been a significant driver of antibiotic resistance.46 Efforts to improve and measure the appropriate use of antibiotics have historically focused on acute care settings. Broad interventions to reduce antibiotic use include prospective audit with intervention and feedback, formulary restriction and preauthorization, and antibiotic time-outs.47,48

Pharmacy-driven interventions include intravenous-to-oral conversions, dose adjustments for organ dysfunction, pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interventions to optimize treatment for organisms with reduced susceptibility, therapeutic duplication alerts, and automatic-stop orders.47,48

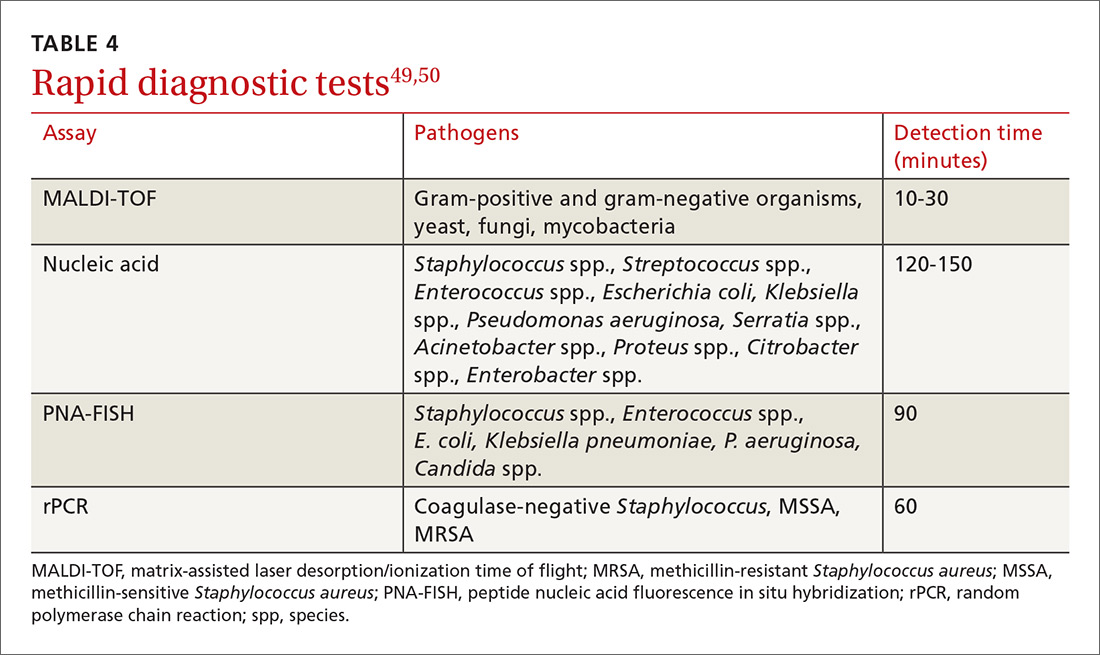

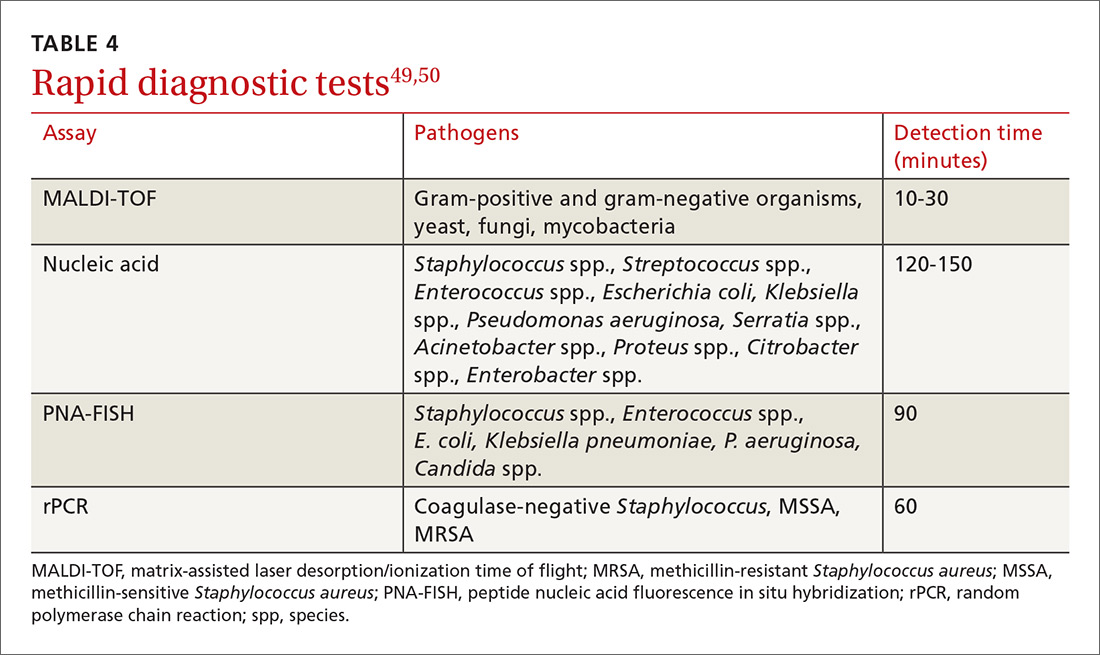

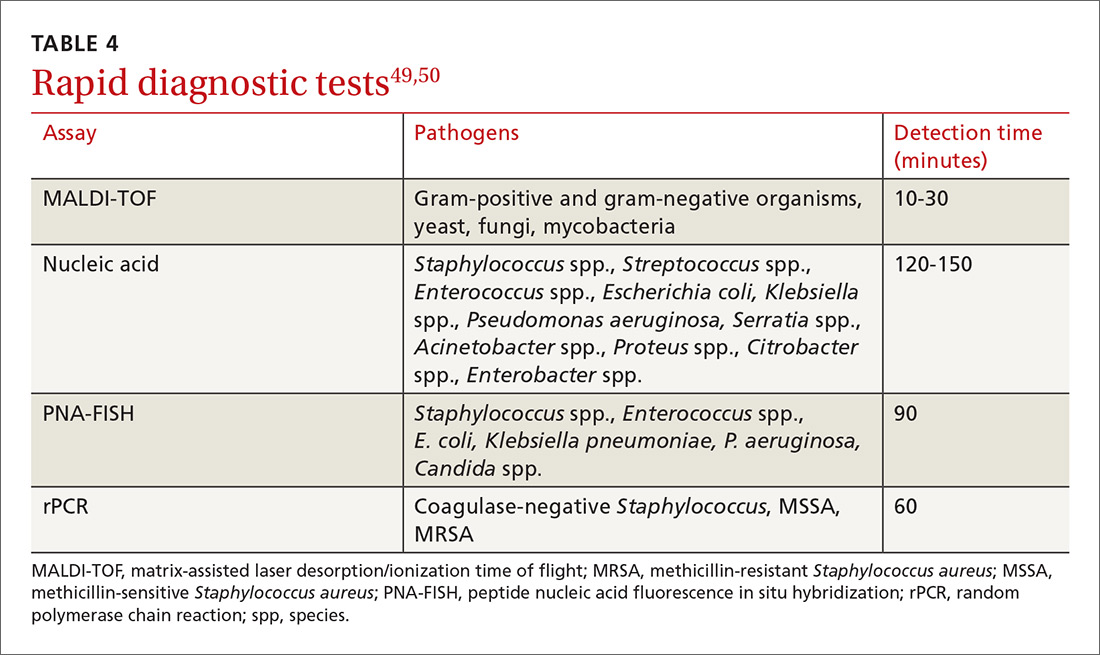

Diagnosis-specific interventions include order sets for common infections and the use of rapid diagnostic assays (TABLE 449,50). Rapid diagnostic testing is increasingly being considered an essential component of stewardship programs because it permits significantly shortened time to organism identification and susceptibility testing and allows for improved antibiotic utilization and patient outcomes when coupled with other effective stewardship strategies.49

Key players in acute care antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) often include physicians, pharmacists, infectious disease specialists, epidemiologists, microbiologists, nurses, and experts in quality improvement and information technology.

The core elements. The CDC has defined the core elements of successful inpatient ASPs.46 These include:

- commitment from hospital leadership

- a physician leader who is responsible for overall program outcomes

- a pharmacist leader who co-leads the program and is accountable for enterprise-wide improvements in antibiotic use

- implementation of at least one systemic intervention (broad, pharmacy-driven, or infection/syndrome-specific)

- monitoring of prescribing and resistance patterns

- reporting antibiotic use and resistance patterns to all involved in the medication use process

- Education directed at the health care team about optimal antibiotic use.

Above all, success with antibiotic stewardship is dependent on identified leadership and an enterprise-wide multidisciplinary approach.

The FP’s role in hospital ASPs can take a number of forms. FPs who practice inpatient medicine should work with all members of their department and be supportive of efforts to improve antibiotic use. Prescribers should help develop and implement hospital-specific treatment recommendations, as well as be responsive to measurements and audits aimed at determining the quantity and quality of antibiotic use. Hospital-specific updates on antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance should be shared widely through formal and informal settings. FPs should know if patients with resistant organisms are hospitalized at institutions where they practice, and should remain abreast of infection rates and resistance patterns.

When admitting a patient, the FP should ask if the patient has received medical care elsewhere, including in another country. When caring for patients known to be currently or previously colonized or infected with resistant organisms, the FP should follow the appropriate precautions and insist that all members of the health care team follow suit.

CASE

A diagnosis of carbapenem-resistant E.coli sepsis is eventually made. Additional susceptibility test results reported later the same day revealed sensitivity to tigecycline and colistin, with intermediate sensitivity to doripenem. An infectious disease expert recommended contact precautions and combination treatment with tigecycline and doripenem for at least 7 days. The addition of a polymyxin was also considered; however, the patient’s renal function was not favorable enough to support a course of that agent. Longer duration of therapy may be required if adequate source control is not achieved.

After a complicated ICU stay, including the need for surgical wound drainage, the patient responded satisfactorily and was transferred to a medical step-down unit for continued recovery and eventual discharge.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dora E. Wiskirchen, PharmD, BCPS, Department of Pharmacy, St. Francis Hospital and Medical Center, 114 Woodland St., Hartford, CT 06105; Email: Dora.Wiskirchen@stfranciscare.org.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2018.

2. Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Benjamin DK Jr, et al. 10 × ‘20 progress—development of new drugs active against gram-negative bacilli: an update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1685-1694.

3. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial use in US acute care hospitals, May-September 2011. JAMA. 2014;312:1438-1446.

4. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e18-e55.

5. Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520-532.

6. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e61-e111.

7. Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e132-e173

8. Wiskirchen DE, Summa M, Perrin A, et al. Antibiotic stewardship: The FP’s role. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:876-885.

9. Stryjewski ME, Corey GR. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an evolving pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58 Suppl 1:S10-S19.

10. Dantes R, Mu Y, Belflower R, et al. National burden of invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, United States, 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1970-1978.

11. Askari E, Tabatabai SM, Arianpoor A, et al. VanA-positive vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: systematic search and review of reported cases. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2013;21:91-93.

12. van Hal SJ, Paterson DL. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the significance of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:405-410.

13. Orbactiv [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: The Medicines Company; 2016. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/206334s000lbl.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2018.

14. Dalvance [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Allergan; 2016. Available at: https://www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/dalvance_pi. Accessed January 10, 2018.

15. Rivera AM, Boucher HW. Current concepts in antimicrobial therapy against select gram-positive organisms: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, penicillin-resistant pneumococci, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:1230-1243.

16. Heintz BH, Halilovic J, Christensen CL. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal urinary tract infections. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:1136-1149.

17. Arias CA, Murray BE. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:266-278.

18. Teflaro [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Allergan; 2016. Available at: http://www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/teflaro_pi. Accessed January 10, 2018.

19. Sivextro [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co; 2015. Available at: https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/s/sivextro/sivextro_pi.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2018.

20. Kanj SS, Kanafani ZA. Current concepts in antimicrobial therapy against resistant gram-negative organisms: extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:250-259.

21. Rodríguez-Baño J, Navarro MD, Retamar P, et al. β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations for the treatment of bacteremia due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli; a post hoc analysis of prospective cohorts. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:167-174.

22. Peterson LR. Antibiotic policy and prescribing strategies for therapy of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: the role of piperacillin-tazobactam. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14 Suppl 1:181-184.

23. Nguyen HM, Shier KL, Graber CJ. Determining a clinical framework for use of cefepime and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors in the treatment of infections caused by extended-spectrum-β-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:871-880.

24. Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the national healthcare safety network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:1-14.

25. Toussaint KA, Gallagher JC. β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations: from then to now. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49:86-98.

26. Curello J, MacDougall C. Beyond susceptible and resistant, part II: treatment of infections due to Gram-negative organisms producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19:156-164.

27. Reffert JL, Smith WJ. Fosfomycin for the treatment of resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:845-857.

28. MacDougall C. Beyond susceptible and resistant, part I: treatment of infections due to Gram-negative organisms with inducible β-lactamases. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16:23-30.

29. Tamma PD, Girdwood SC, Gopaul R, et al. The use of cefepime for treating AmpC β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:781-788.

30. Morrill HJ, Pogue JM, Kaye KS, et al. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:1-15.

31. Qureshi ZA, Paterson DL, Potoski BA, et al. Treatment of bacteremia due to KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumonia: superiority of combination antimicrobial regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2108-2113.

32. Tumbarello M, Viale P, Viscoli C, et al. Predictors of morality in bloodstream infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumonia: importance of combination therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:943-950.

33. Giamarellou H, Galani L, Baziaka F, et al. Effectiveness of a double-carbapenem regimen for infections in humans due to carbapenemase-producing pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2388-2390.

34. Ceccarelli G, Falcone M, Giordano A, et al. Successful ertapenem-doripenem combination treatment of bacteremic ventilator-associated pneumonia due to colistin-resistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2900-2901.

35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Facility guidance for control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/cre/CRE-guidance-508.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2018.

36. Crandon JL, Nicolau DP. Pharmacodynamic approaches to optimizing beta-lactam therapy. Crit Car Clin. 2011;27:77-93.

37. Zavascki AP, Carvalhaes CG, Picão RC, et al. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii: resistance mechanisms and implications for therapy. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:71-93.

38. Crandon JL, Ariano RE, Zelenitsky SA, et al. Optimization of meropenem dosage in the critically ill population based on renal function. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:632-638.

39. Ortwine JK, Kaye KS, Li J, et al. Colistin: understanding and applying recent pharmacokinetic advances. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:11-16.

40. Adnan S, Paterson DL, Lipman J, et al. Ampicillin/sulbactam: its potential use in treating infections in critically ill patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013:42:384-389.

41. Munoz-Price LS, Weinstein RA, et al. Acinetobacter infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1271-1281.

42. Pogue JM, Mann T, Barber KE, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: epidemiology, surveillance and management. Expert Rev of Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:383-393.

43. Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:597-602.

44. Moellering RC Jr. NDM-1—a cause for worldwide concern. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2377-2379.

45. Rasheed JK, Kitchel B, Zhu W, et al. New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:870-878.

46. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. The core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/healthcare/pdfs/core-elements.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2018.

47. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE Jr, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:159-177.

48. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antimicrobial stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of American and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016:62:e51-e77.

49. Bauer KA, Perez KK, Forrest GN, et al. Review of rapid diagnostic tests used by antimicrobial stewardship programs. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59 Suppl 3:S134-S145.

50. Wong Y. An introduction to antimicrobial rapid diagnostic testing. Pharmacy One Source 2015. Available at: http://blog.pharmacyonesource.com/an-introduction-to-antimicrobial-rapid-diagnostic-testing. Accessed July 20, 2015.

51. Pakyz AL, MacDougall C, Oinonen M, et al. Trends in antibacterial use in US academic health centers: 2002 to 2006. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2254-2260.

52. Polk RE, Fox C, Mahoney A, et al. Measurement of adult antibacterial drug use in 130 US hospitals: comparison of defined daily dose and days of therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:664-670.

53. Toth NR, Chambers RM, Davis SL. Implementation of a care bundle for antimicrobial stewardship. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:746-749.

CASE

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital from home with acute onset, unrelenting, upper abdominal pain radiating to the back and nausea/vomiting. Her medical history includes bile duct obstruction secondary to gall stones, which was managed in another facility 6 days earlier with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and stenting. The patient has type 2 diabetes (managed with metformin and glargine insulin), hypertension (managed with lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide), and cholesterolemia (managed with atorvastatin).

On admission, the patient's white blood cell count is 14.7 x 103 cells/mm3, heart rate is 100 bpm, blood pressure is 90/68 mm Hg, and temperature is 101.5° F. Serum amylase and lipase are 3 and 2 times the upper limit of normal, respectively. A working diagnosis of acute pancreatitis with sepsis is made. Blood cultures are drawn. A computed tomography scan confirms acute pancreatitis. She receives one dose of meropenem, is started on intravenous fluids and morphine, and is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management.

Her ICU course is complicated by worsening sepsis despite aggressive fluid resuscitation, nutrition, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. On post-admission Day 2, blood culture results reveal Escherichia coli that is resistant to gentamicin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, ceftriaxone, piperacillin/tazobactam, imipenem, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline. Additional susceptibility testing is ordered.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conservatively estimates that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are responsible for 2 billion infections annually, resulting in approximately 23,000 deaths and $20 billion in excess health care expenditures annually.1 Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria typically require longer hospitalizations, more expensive drug therapies, and additional follow-up visits.1 They also result in greater morbidity and mortality compared with similar infections involving non-resistant bacteria.1 To compound the problem, antibiotic development has steadily declined over the last 3 decades, with few novel antimicrobials developed in recent years.2 The most recently approved antibiotics with new mechanisms of action were linezolid in 2000 and daptomycin in 2003, preceded by the carbapenems 15 years earlier. (See “New antimicrobials in the pipeline.”)

New antimicrobials in the pipeline

The Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act was signed into law in 2012, creating a new designation—qualified infectious diseases products (QIDPs)—for antibiotics in development for serious or life-threatening infections (https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ144/PLAW-112publ144.pdf). QIDPs are granted expedited FDA approval and an additional 5 years of patent exclusivity in order to encourage new antimicrobial development.

Five antibiotics have been approved with the QIDP designation: tedizolid, dalbavancin, oritavancin, ceftolozane/tazobactam, and ceftazidime/avibactam, and 20 more agents are in development including a new fluoroquinolone, delafloxacin, for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections including those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and a new tetracycline, eravacycline, for complicated intra-abdominal infections and complicated UTIs. Eravacycline has in vitro activity against penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, MRSA, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, and multidrug-resistant A. baumannii. Both drugs will be available in intravenous and oral formulations.

Greater efforts aimed at using antimicrobials sparingly and appropriately, as well as developing new antimicrobials with activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens, are ultimately needed to address the threat of antimicrobial resistance. This article describes the evidence-based management of inpatient infections caused by resistant bacteria and the role family physicians (FPs) can play in reducing further development of resistance through antimicrobial stewardship practices.

Health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

S. aureus is a common culprit of hospital-acquired infections, including central line-associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and nosocomial skin and soft tissue infections. In fact, nearly half of all isolates from these infections are reported to be methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).3

Patients at greatest risk for MRSA infections include those who have been recently hospitalized, those receiving recent antibiotic therapy or surgery, long-term care residents, intravenous drug abusers, immunocompromised patients, hemodialysis patients, military personnel, and athletes who play contact sports.4,5 Patients with these infections often require the use of an anti-MRSA agent (eg, vancomycin, linezolid) in empiric antibiotic regimens.6,7 The focus of this discussion is on MRSA in hospital and long-term care settings; a discussion of community-acquired MRSA is addressed elsewhere. (See “Antibiotic stewardship: The FP’s role,” J Fam Pract. 2016;65:876-885.8)

Efforts are working, but problems remain. MRSA accounts for almost 60% of S. aureus isolates in ICUs.9 Thankfully, rates of health care-associated MRSA are now either static or declining nationwide, as a result of major initiatives targeted toward preventing health care-associated infection in recent years.10

Methicillin resistance in S. aureus results from expression of PBP2a, an altered penicillin-binding protein with reduced binding affinity for beta-lactam antibiotics. As a result, MRSA isolates are resistant to most beta-lactams.9 Resistance to macrolides, azithromycin, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin is also common in health care-associated MRSA.9

The first case of true vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) in the United States was reported in 2002.11 Fortunately, both VRSA and vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) have remained rare throughout the United States and abroad.9,11 Heterogeneous VISA (hVISA), which is characterized by a few resistant subpopulations within a fully susceptible population of S. aureus, is more common than VRSA or VISA. Unfortunately, hVISA is difficult to detect using commercially available susceptibility tests. This can result in treatment failure with vancomycin, even though the MRSA isolate may appear fully susceptible and the patient has received clinically appropriate doses of the drug.12

Treatment. Vancomycin is the mainstay of therapy for many systemic health care-associated MRSA infections. Alternative therapies (daptomycin or linezolid) should be considered for isolates with a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) >2 mcg/mL or in the setting of a poor clinical response.4 Combination therapy may be warranted in the setting of treatment failure. Because comparative efficacy data for alternative therapies is lacking, agent selection should be tailored to the site of infection and patient-specific factors such as allergies, drug interactions, and the risk for adverse events (TABLE 113-17).

Ceftaroline, the only beta-lactam with activity against MRSA, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSIs) and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia.18 Tedizolid, a new oxazolidinone similar to linezolid, as well as oritavancin and dalbavancin—2 long-acting glycopeptides—were also recently approved for use with ABSSIs.13,14,19

Oritavancin and dalbavancin both have dosing regimens that may allow for earlier hospital discharge or treatment in an outpatient setting.13,14 Telavancin, quinupristin/dalfopristin, and tigecycline are typically reserved for salvage therapy due to adverse event profiles and/or limited efficacy data.15

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE)

Enterococci are typically considered normal gastrointestinal tract flora. However, antibiotic exposure can alter gut flora allowing for VRE colonization, which in some instances, can progress to the development of a health care-associated infection.15 Therefore, it is important to distinguish whether a patient is colonized or infected with VRE because treatment of colonization is unnecessary and may lead to resistance and other adverse effects.15

Enterococci may be the culprit in nosocomially-acquired intra-abdominal infections, bacteremia, endocarditis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and skin and skin structure infections, and can exhibit resistance to ampicillin, aminoglycosides, and vancomycin.15 VRE is predominantly a health care-associated pathogen and may account for up to 77% of all health care-associated Enterococcus faecium infections and 9% of Enterococcus faecalis infections.1

Treatment. Antibiotic selection for VRE infections depends upon the site of infection, patient comorbidities, the potential for drug interactions, and treatment duration. Current treatment options include linezolid, daptomycin, quinupristin/dalfopristin (for E. faecium only), tigecycline, and ampicillin if the organism is susceptible (TABLE 113-17).15 For cystitis caused by VRE (not urinary colonization), fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin are additional options.16

Resistant Enterobacteriaceae

Resistant Enterobacteriaceae such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae have emerged as a result of increased broad-spectrum antibiotic utilization and have been implicated in health care-associated UTIs, intra-abdominal infections, bacteremia, and even pneumonia.1 Patients with prolonged hospital stays and invasive medical devices, such as urinary and vascular catheters, endotracheal tubes, and endoscopy scopes, have the highest risk for infection with these organisms.20

The genotypic profiles of resistance among the Enterobacteriaceae are diverse and complex, resulting in different levels of activity for the various beta-lactam agents (TABLE 221-24).25 Furthermore, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producers and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are often resistant to other classes of antibiotics, too, including aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones.20,25 The increasing diversity among beta-lactamase enzymes has made the selection of appropriate antibiotic therapy challenging, since the ability to identify specific beta-lactamase genes is not yet available in the clinical setting.

ESBLs emerged shortly after the widespread use of cephalosporins in practice and are resistant to a variety of beta-lactams (TABLE 221-24). Carbapenems are considered the mainstay of therapy for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.20,26 An alternative for urinary and biliary tract infections can be piperacillin-tazobactam,21,26 but the combination may be subject to the inoculum effect, in which MIC and risk for treatment failure increase in infections with a high bacterial burden (colony-forming units/mL) such as pneumonias (TABLE 320,22,,23,25,27-42).22

Cefepime may retain activity against some ESBL-producing isolates, but it is also susceptible to the inoculum effect and should only be used for non–life-threatening infections and at higher doses.23 Fosfomycin has activity against ESBL-producing bacteria, but is only approved for oral use in UTIs in the United States.20,27 Ceftolozane/tazobactam (Zerbaxa) and ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz) were approved in 2014 and 2015, respectively, by the FDA for the management of complicated urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections caused by susceptible ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. In order to preserve the antimicrobial efficacy of these 2 newer agents, however, they are typically reserved for definitive therapy when in vitro susceptibility is demonstrated and there are no other viable options.

AmpC beta-lactamases are resistant to similar agents as the ESBLs, in addition to cefoxitin and the beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations containing clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and in some cases, tazobactam. Resistance can be induced and emerges in certain pathogens while patients are on therapy.28 Fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides have a low risk of developing resistance while patients are on therapy, but are more likely to cause adverse effects and toxicity compared with the beta-lactams.28 Carbapenems have the lowest risk of emerging resistance and are the empiric treatment of choice for known AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in serious infections.20,28 Cefepime may also be an option in less severe infections, such as UTIs or those in which adequate source control has been achieved.28,29

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) have become a serious threat as a result of increased carbapenem use. While carbapenem resistance is less common in the United States than worldwide, rates have increased nearly 4-fold (1.2% to 4.2%) in the last decade, with some regions of the country experiencing substantially higher rates.24 The most commonly reported CRE genotypes identified in the United States include the serine carbapenemase (K. pneumoniae carbapenemase, or KPC), and the metallo-beta-lactamases (Verona integrin-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase, or VIM, and the New Dehli metallo-beta-lactamase, or NDM), with each class conferring slightly different resistance patterns (TABLE 221-24).20,30

Few treatment options exist for Enterobacteriaceae producing a serine carbapenemase, and, unfortunately, evidence to support these therapies is extremely limited. Some CRE isolates retain susceptibility to the polymyxins, the aminoglycosides, and tigecycline.30 Even fewer options exist for treating Enterobacteriaceae producing metallo-beta-lactamases, which are typically only susceptible to the polymyxins and tigecycline.43-45

Several studies have demonstrated lower mortality rates when combination therapy is utilized for CRE bloodstream infections.31,32 Furthermore, the combination of colistin, tigecycline, and meropenem was found to have a significant mortality advantage.32 Double carbapenem therapy has been effective in several cases of invasive KPC-producing K. pneumoniae infections.33,34 However, it is important to note that current clinical evidence comes from small, single-center, retrospective studies, and additional research is needed to determine optimal combinations and dosing strategies for these infections.

Lastly, ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz) was recently approved for the treatment of complicated urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections, and has activity against KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae, but not those producing metallo-beta-lactamases, like VIM or NDM. In the absence of strong evidence to support one therapy over another, it may be reasonable to select at least 2 active agents when treating serious CRE infections. Agent selection should be based on the site of the infection, susceptibility data, and patient-specific factors (TABLE 320,22,,23,25,27-42). The CDC also recommends contact precautions for patients who are colonized or infected with CRE.35

Multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative rod that can be isolated from nosocomial infections such as UTIs, bacteremias, pneumonias, skin and skin structure infections, and burn infections.20 Pseudomonal infections are associated with high morbidity and mortality and can cause recurrent infections in patients with cystic fibrosis.20 Multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa (MDR-P) infections account for approximately 13% of all health care-associated pseudomonal infections nationally.1 Both fluoroquinolone and aminoglycoside resistance has emerged, and multiple types of beta-lactamases (ESBL, AmpC, carbapenemases) have resulted in organisms that are resistant to nearly all anti-pseudomonal beta-lactams.20

Treatment. For patients at risk for MDR-P, some clinical practice guidelines have recommended using an empiric therapy regimen that contains antimicrobial agents from 2 different classes with activity against P. aeruginosa to increase the likelihood of susceptibility to at least one agent.6 De-escalation can occur once culture and susceptibility results are available.6 Dose optimization based on pharmacodynamic principles is critical for ensuring clinical efficacy and minimizing resistance.36 The use of high-dose, prolonged-infusion beta-lactams (piperacillin/tazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, and carbapenems) is becoming common practice at institutions with higher rates of resistance.36-38

A resurgence of polymyxin (colistin) use for MDR-P isolates has occurred, and may be warranted empirically in select patients, based on local resistance patterns and patient history. Newer pharmacokinetic data are available, resulting in improved dosing strategies that may enhance efficacy while alleviating some of the nephrotoxicity concerns associated with colistin therapy.39

Ceftolozane/tazobactam (Zerbaxa) and ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz) are options for complicated urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections caused by susceptible P. aeruginosa isolates. Given the lack of comparative efficacy data available for the management of MDR-P infections, agent selection should be based on site of infection, susceptibility data, and patient-specific factors.

Multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

A. baumannii is a lactose-fermenting, gram-negative rod sometimes implicated in nosocomial pneumonias, line-related bloodstream infections, UTIs, and surgical site infections.20 Resistance has been documented for nearly all classes of antibiotics, including carbapenems.1,20 Over half of all health care-associated A. baumannii isolates in the United States are multidrug resistant.1

Treatment. Therapy options for A. baumannii infections are often limited to polymyxins, tigecycline, carbapenems (except ertapenem), aminoglycosides, and high-dose ampicillin/sulbactam, depending on in vitro susceptibilities.40,41 When using ampicillin/sulbactam for A. baumannii infections, sulbactam is the active ingredient. Doses of 2 to 4 g/d of sulbactam have demonstrated efficacy in non-critically ill patients, while critically ill patients may require higher doses (up to 12 g/d).40 Colistin is considered the mainstay of therapy for carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii. It should be used in combination with either a carbapenem, rifampin, an aminoglycoside, or tigecycline.42

Drug therapies for nosocomial-resistant gram-negative infections, along with clinical pearls for use, are summarized in TABLE 3.20,22,23,25,27-42 Because efficacy data are limited for treating infections caused by these pathogens, appropriate antimicrobial selection is frequently guided by location of infection, susceptibility patterns, and patient-specific factors such as allergies and the risk for adverse effects.

Antimicrobial stewardship

Antibiotic misuse has been a significant driver of antibiotic resistance.46 Efforts to improve and measure the appropriate use of antibiotics have historically focused on acute care settings. Broad interventions to reduce antibiotic use include prospective audit with intervention and feedback, formulary restriction and preauthorization, and antibiotic time-outs.47,48

Pharmacy-driven interventions include intravenous-to-oral conversions, dose adjustments for organ dysfunction, pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interventions to optimize treatment for organisms with reduced susceptibility, therapeutic duplication alerts, and automatic-stop orders.47,48

Diagnosis-specific interventions include order sets for common infections and the use of rapid diagnostic assays (TABLE 449,50). Rapid diagnostic testing is increasingly being considered an essential component of stewardship programs because it permits significantly shortened time to organism identification and susceptibility testing and allows for improved antibiotic utilization and patient outcomes when coupled with other effective stewardship strategies.49

Key players in acute care antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) often include physicians, pharmacists, infectious disease specialists, epidemiologists, microbiologists, nurses, and experts in quality improvement and information technology.

The core elements. The CDC has defined the core elements of successful inpatient ASPs.46 These include:

- commitment from hospital leadership

- a physician leader who is responsible for overall program outcomes

- a pharmacist leader who co-leads the program and is accountable for enterprise-wide improvements in antibiotic use

- implementation of at least one systemic intervention (broad, pharmacy-driven, or infection/syndrome-specific)

- monitoring of prescribing and resistance patterns

- reporting antibiotic use and resistance patterns to all involved in the medication use process

- Education directed at the health care team about optimal antibiotic use.

Above all, success with antibiotic stewardship is dependent on identified leadership and an enterprise-wide multidisciplinary approach.

The FP’s role in hospital ASPs can take a number of forms. FPs who practice inpatient medicine should work with all members of their department and be supportive of efforts to improve antibiotic use. Prescribers should help develop and implement hospital-specific treatment recommendations, as well as be responsive to measurements and audits aimed at determining the quantity and quality of antibiotic use. Hospital-specific updates on antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance should be shared widely through formal and informal settings. FPs should know if patients with resistant organisms are hospitalized at institutions where they practice, and should remain abreast of infection rates and resistance patterns.

When admitting a patient, the FP should ask if the patient has received medical care elsewhere, including in another country. When caring for patients known to be currently or previously colonized or infected with resistant organisms, the FP should follow the appropriate precautions and insist that all members of the health care team follow suit.

CASE

A diagnosis of carbapenem-resistant E.coli sepsis is eventually made. Additional susceptibility test results reported later the same day revealed sensitivity to tigecycline and colistin, with intermediate sensitivity to doripenem. An infectious disease expert recommended contact precautions and combination treatment with tigecycline and doripenem for at least 7 days. The addition of a polymyxin was also considered; however, the patient’s renal function was not favorable enough to support a course of that agent. Longer duration of therapy may be required if adequate source control is not achieved.

After a complicated ICU stay, including the need for surgical wound drainage, the patient responded satisfactorily and was transferred to a medical step-down unit for continued recovery and eventual discharge.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dora E. Wiskirchen, PharmD, BCPS, Department of Pharmacy, St. Francis Hospital and Medical Center, 114 Woodland St., Hartford, CT 06105; Email: Dora.Wiskirchen@stfranciscare.org.

CASE

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital from home with acute onset, unrelenting, upper abdominal pain radiating to the back and nausea/vomiting. Her medical history includes bile duct obstruction secondary to gall stones, which was managed in another facility 6 days earlier with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and stenting. The patient has type 2 diabetes (managed with metformin and glargine insulin), hypertension (managed with lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide), and cholesterolemia (managed with atorvastatin).

On admission, the patient's white blood cell count is 14.7 x 103 cells/mm3, heart rate is 100 bpm, blood pressure is 90/68 mm Hg, and temperature is 101.5° F. Serum amylase and lipase are 3 and 2 times the upper limit of normal, respectively. A working diagnosis of acute pancreatitis with sepsis is made. Blood cultures are drawn. A computed tomography scan confirms acute pancreatitis. She receives one dose of meropenem, is started on intravenous fluids and morphine, and is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management.

Her ICU course is complicated by worsening sepsis despite aggressive fluid resuscitation, nutrition, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. On post-admission Day 2, blood culture results reveal Escherichia coli that is resistant to gentamicin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, ceftriaxone, piperacillin/tazobactam, imipenem, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline. Additional susceptibility testing is ordered.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conservatively estimates that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are responsible for 2 billion infections annually, resulting in approximately 23,000 deaths and $20 billion in excess health care expenditures annually.1 Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria typically require longer hospitalizations, more expensive drug therapies, and additional follow-up visits.1 They also result in greater morbidity and mortality compared with similar infections involving non-resistant bacteria.1 To compound the problem, antibiotic development has steadily declined over the last 3 decades, with few novel antimicrobials developed in recent years.2 The most recently approved antibiotics with new mechanisms of action were linezolid in 2000 and daptomycin in 2003, preceded by the carbapenems 15 years earlier. (See “New antimicrobials in the pipeline.”)

New antimicrobials in the pipeline

The Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act was signed into law in 2012, creating a new designation—qualified infectious diseases products (QIDPs)—for antibiotics in development for serious or life-threatening infections (https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ144/PLAW-112publ144.pdf). QIDPs are granted expedited FDA approval and an additional 5 years of patent exclusivity in order to encourage new antimicrobial development.

Five antibiotics have been approved with the QIDP designation: tedizolid, dalbavancin, oritavancin, ceftolozane/tazobactam, and ceftazidime/avibactam, and 20 more agents are in development including a new fluoroquinolone, delafloxacin, for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections including those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and a new tetracycline, eravacycline, for complicated intra-abdominal infections and complicated UTIs. Eravacycline has in vitro activity against penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, MRSA, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, and multidrug-resistant A. baumannii. Both drugs will be available in intravenous and oral formulations.

Greater efforts aimed at using antimicrobials sparingly and appropriately, as well as developing new antimicrobials with activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens, are ultimately needed to address the threat of antimicrobial resistance. This article describes the evidence-based management of inpatient infections caused by resistant bacteria and the role family physicians (FPs) can play in reducing further development of resistance through antimicrobial stewardship practices.

Health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

S. aureus is a common culprit of hospital-acquired infections, including central line-associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and nosocomial skin and soft tissue infections. In fact, nearly half of all isolates from these infections are reported to be methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).3

Patients at greatest risk for MRSA infections include those who have been recently hospitalized, those receiving recent antibiotic therapy or surgery, long-term care residents, intravenous drug abusers, immunocompromised patients, hemodialysis patients, military personnel, and athletes who play contact sports.4,5 Patients with these infections often require the use of an anti-MRSA agent (eg, vancomycin, linezolid) in empiric antibiotic regimens.6,7 The focus of this discussion is on MRSA in hospital and long-term care settings; a discussion of community-acquired MRSA is addressed elsewhere. (See “Antibiotic stewardship: The FP’s role,” J Fam Pract. 2016;65:876-885.8)

Efforts are working, but problems remain. MRSA accounts for almost 60% of S. aureus isolates in ICUs.9 Thankfully, rates of health care-associated MRSA are now either static or declining nationwide, as a result of major initiatives targeted toward preventing health care-associated infection in recent years.10

Methicillin resistance in S. aureus results from expression of PBP2a, an altered penicillin-binding protein with reduced binding affinity for beta-lactam antibiotics. As a result, MRSA isolates are resistant to most beta-lactams.9 Resistance to macrolides, azithromycin, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin is also common in health care-associated MRSA.9

The first case of true vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) in the United States was reported in 2002.11 Fortunately, both VRSA and vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) have remained rare throughout the United States and abroad.9,11 Heterogeneous VISA (hVISA), which is characterized by a few resistant subpopulations within a fully susceptible population of S. aureus, is more common than VRSA or VISA. Unfortunately, hVISA is difficult to detect using commercially available susceptibility tests. This can result in treatment failure with vancomycin, even though the MRSA isolate may appear fully susceptible and the patient has received clinically appropriate doses of the drug.12

Treatment. Vancomycin is the mainstay of therapy for many systemic health care-associated MRSA infections. Alternative therapies (daptomycin or linezolid) should be considered for isolates with a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) >2 mcg/mL or in the setting of a poor clinical response.4 Combination therapy may be warranted in the setting of treatment failure. Because comparative efficacy data for alternative therapies is lacking, agent selection should be tailored to the site of infection and patient-specific factors such as allergies, drug interactions, and the risk for adverse events (TABLE 113-17).

Ceftaroline, the only beta-lactam with activity against MRSA, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSIs) and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia.18 Tedizolid, a new oxazolidinone similar to linezolid, as well as oritavancin and dalbavancin—2 long-acting glycopeptides—were also recently approved for use with ABSSIs.13,14,19

Oritavancin and dalbavancin both have dosing regimens that may allow for earlier hospital discharge or treatment in an outpatient setting.13,14 Telavancin, quinupristin/dalfopristin, and tigecycline are typically reserved for salvage therapy due to adverse event profiles and/or limited efficacy data.15

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE)

Enterococci are typically considered normal gastrointestinal tract flora. However, antibiotic exposure can alter gut flora allowing for VRE colonization, which in some instances, can progress to the development of a health care-associated infection.15 Therefore, it is important to distinguish whether a patient is colonized or infected with VRE because treatment of colonization is unnecessary and may lead to resistance and other adverse effects.15

Enterococci may be the culprit in nosocomially-acquired intra-abdominal infections, bacteremia, endocarditis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and skin and skin structure infections, and can exhibit resistance to ampicillin, aminoglycosides, and vancomycin.15 VRE is predominantly a health care-associated pathogen and may account for up to 77% of all health care-associated Enterococcus faecium infections and 9% of Enterococcus faecalis infections.1

Treatment. Antibiotic selection for VRE infections depends upon the site of infection, patient comorbidities, the potential for drug interactions, and treatment duration. Current treatment options include linezolid, daptomycin, quinupristin/dalfopristin (for E. faecium only), tigecycline, and ampicillin if the organism is susceptible (TABLE 113-17).15 For cystitis caused by VRE (not urinary colonization), fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin are additional options.16

Resistant Enterobacteriaceae

Resistant Enterobacteriaceae such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae have emerged as a result of increased broad-spectrum antibiotic utilization and have been implicated in health care-associated UTIs, intra-abdominal infections, bacteremia, and even pneumonia.1 Patients with prolonged hospital stays and invasive medical devices, such as urinary and vascular catheters, endotracheal tubes, and endoscopy scopes, have the highest risk for infection with these organisms.20

The genotypic profiles of resistance among the Enterobacteriaceae are diverse and complex, resulting in different levels of activity for the various beta-lactam agents (TABLE 221-24).25 Furthermore, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producers and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are often resistant to other classes of antibiotics, too, including aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones.20,25 The increasing diversity among beta-lactamase enzymes has made the selection of appropriate antibiotic therapy challenging, since the ability to identify specific beta-lactamase genes is not yet available in the clinical setting.

ESBLs emerged shortly after the widespread use of cephalosporins in practice and are resistant to a variety of beta-lactams (TABLE 221-24). Carbapenems are considered the mainstay of therapy for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.20,26 An alternative for urinary and biliary tract infections can be piperacillin-tazobactam,21,26 but the combination may be subject to the inoculum effect, in which MIC and risk for treatment failure increase in infections with a high bacterial burden (colony-forming units/mL) such as pneumonias (TABLE 320,22,,23,25,27-42).22

Cefepime may retain activity against some ESBL-producing isolates, but it is also susceptible to the inoculum effect and should only be used for non–life-threatening infections and at higher doses.23 Fosfomycin has activity against ESBL-producing bacteria, but is only approved for oral use in UTIs in the United States.20,27 Ceftolozane/tazobactam (Zerbaxa) and ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz) were approved in 2014 and 2015, respectively, by the FDA for the management of complicated urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections caused by susceptible ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. In order to preserve the antimicrobial efficacy of these 2 newer agents, however, they are typically reserved for definitive therapy when in vitro susceptibility is demonstrated and there are no other viable options.

AmpC beta-lactamases are resistant to similar agents as the ESBLs, in addition to cefoxitin and the beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations containing clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and in some cases, tazobactam. Resistance can be induced and emerges in certain pathogens while patients are on therapy.28 Fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides have a low risk of developing resistance while patients are on therapy, but are more likely to cause adverse effects and toxicity compared with the beta-lactams.28 Carbapenems have the lowest risk of emerging resistance and are the empiric treatment of choice for known AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in serious infections.20,28 Cefepime may also be an option in less severe infections, such as UTIs or those in which adequate source control has been achieved.28,29

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) have become a serious threat as a result of increased carbapenem use. While carbapenem resistance is less common in the United States than worldwide, rates have increased nearly 4-fold (1.2% to 4.2%) in the last decade, with some regions of the country experiencing substantially higher rates.24 The most commonly reported CRE genotypes identified in the United States include the serine carbapenemase (K. pneumoniae carbapenemase, or KPC), and the metallo-beta-lactamases (Verona integrin-encoded metallo-beta-lactamase, or VIM, and the New Dehli metallo-beta-lactamase, or NDM), with each class conferring slightly different resistance patterns (TABLE 221-24).20,30

Few treatment options exist for Enterobacteriaceae producing a serine carbapenemase, and, unfortunately, evidence to support these therapies is extremely limited. Some CRE isolates retain susceptibility to the polymyxins, the aminoglycosides, and tigecycline.30 Even fewer options exist for treating Enterobacteriaceae producing metallo-beta-lactamases, which are typically only susceptible to the polymyxins and tigecycline.43-45

Several studies have demonstrated lower mortality rates when combination therapy is utilized for CRE bloodstream infections.31,32 Furthermore, the combination of colistin, tigecycline, and meropenem was found to have a significant mortality advantage.32 Double carbapenem therapy has been effective in several cases of invasive KPC-producing K. pneumoniae infections.33,34 However, it is important to note that current clinical evidence comes from small, single-center, retrospective studies, and additional research is needed to determine optimal combinations and dosing strategies for these infections.

Lastly, ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz) was recently approved for the treatment of complicated urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections, and has activity against KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae, but not those producing metallo-beta-lactamases, like VIM or NDM. In the absence of strong evidence to support one therapy over another, it may be reasonable to select at least 2 active agents when treating serious CRE infections. Agent selection should be based on the site of the infection, susceptibility data, and patient-specific factors (TABLE 320,22,,23,25,27-42). The CDC also recommends contact precautions for patients who are colonized or infected with CRE.35

Multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative rod that can be isolated from nosocomial infections such as UTIs, bacteremias, pneumonias, skin and skin structure infections, and burn infections.20 Pseudomonal infections are associated with high morbidity and mortality and can cause recurrent infections in patients with cystic fibrosis.20 Multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa (MDR-P) infections account for approximately 13% of all health care-associated pseudomonal infections nationally.1 Both fluoroquinolone and aminoglycoside resistance has emerged, and multiple types of beta-lactamases (ESBL, AmpC, carbapenemases) have resulted in organisms that are resistant to nearly all anti-pseudomonal beta-lactams.20

Treatment. For patients at risk for MDR-P, some clinical practice guidelines have recommended using an empiric therapy regimen that contains antimicrobial agents from 2 different classes with activity against P. aeruginosa to increase the likelihood of susceptibility to at least one agent.6 De-escalation can occur once culture and susceptibility results are available.6 Dose optimization based on pharmacodynamic principles is critical for ensuring clinical efficacy and minimizing resistance.36 The use of high-dose, prolonged-infusion beta-lactams (piperacillin/tazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, and carbapenems) is becoming common practice at institutions with higher rates of resistance.36-38

A resurgence of polymyxin (colistin) use for MDR-P isolates has occurred, and may be warranted empirically in select patients, based on local resistance patterns and patient history. Newer pharmacokinetic data are available, resulting in improved dosing strategies that may enhance efficacy while alleviating some of the nephrotoxicity concerns associated with colistin therapy.39

Ceftolozane/tazobactam (Zerbaxa) and ceftazidime/avibactam (Avycaz) are options for complicated urinary tract and intra-abdominal infections caused by susceptible P. aeruginosa isolates. Given the lack of comparative efficacy data available for the management of MDR-P infections, agent selection should be based on site of infection, susceptibility data, and patient-specific factors.

Multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

A. baumannii is a lactose-fermenting, gram-negative rod sometimes implicated in nosocomial pneumonias, line-related bloodstream infections, UTIs, and surgical site infections.20 Resistance has been documented for nearly all classes of antibiotics, including carbapenems.1,20 Over half of all health care-associated A. baumannii isolates in the United States are multidrug resistant.1

Treatment. Therapy options for A. baumannii infections are often limited to polymyxins, tigecycline, carbapenems (except ertapenem), aminoglycosides, and high-dose ampicillin/sulbactam, depending on in vitro susceptibilities.40,41 When using ampicillin/sulbactam for A. baumannii infections, sulbactam is the active ingredient. Doses of 2 to 4 g/d of sulbactam have demonstrated efficacy in non-critically ill patients, while critically ill patients may require higher doses (up to 12 g/d).40 Colistin is considered the mainstay of therapy for carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii. It should be used in combination with either a carbapenem, rifampin, an aminoglycoside, or tigecycline.42

Drug therapies for nosocomial-resistant gram-negative infections, along with clinical pearls for use, are summarized in TABLE 3.20,22,23,25,27-42 Because efficacy data are limited for treating infections caused by these pathogens, appropriate antimicrobial selection is frequently guided by location of infection, susceptibility patterns, and patient-specific factors such as allergies and the risk for adverse effects.

Antimicrobial stewardship

Antibiotic misuse has been a significant driver of antibiotic resistance.46 Efforts to improve and measure the appropriate use of antibiotics have historically focused on acute care settings. Broad interventions to reduce antibiotic use include prospective audit with intervention and feedback, formulary restriction and preauthorization, and antibiotic time-outs.47,48

Pharmacy-driven interventions include intravenous-to-oral conversions, dose adjustments for organ dysfunction, pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interventions to optimize treatment for organisms with reduced susceptibility, therapeutic duplication alerts, and automatic-stop orders.47,48

Diagnosis-specific interventions include order sets for common infections and the use of rapid diagnostic assays (TABLE 449,50). Rapid diagnostic testing is increasingly being considered an essential component of stewardship programs because it permits significantly shortened time to organism identification and susceptibility testing and allows for improved antibiotic utilization and patient outcomes when coupled with other effective stewardship strategies.49

Key players in acute care antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) often include physicians, pharmacists, infectious disease specialists, epidemiologists, microbiologists, nurses, and experts in quality improvement and information technology.

The core elements. The CDC has defined the core elements of successful inpatient ASPs.46 These include:

- commitment from hospital leadership

- a physician leader who is responsible for overall program outcomes

- a pharmacist leader who co-leads the program and is accountable for enterprise-wide improvements in antibiotic use

- implementation of at least one systemic intervention (broad, pharmacy-driven, or infection/syndrome-specific)

- monitoring of prescribing and resistance patterns

- reporting antibiotic use and resistance patterns to all involved in the medication use process

- Education directed at the health care team about optimal antibiotic use.

Above all, success with antibiotic stewardship is dependent on identified leadership and an enterprise-wide multidisciplinary approach.

The FP’s role in hospital ASPs can take a number of forms. FPs who practice inpatient medicine should work with all members of their department and be supportive of efforts to improve antibiotic use. Prescribers should help develop and implement hospital-specific treatment recommendations, as well as be responsive to measurements and audits aimed at determining the quantity and quality of antibiotic use. Hospital-specific updates on antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance should be shared widely through formal and informal settings. FPs should know if patients with resistant organisms are hospitalized at institutions where they practice, and should remain abreast of infection rates and resistance patterns.

When admitting a patient, the FP should ask if the patient has received medical care elsewhere, including in another country. When caring for patients known to be currently or previously colonized or infected with resistant organisms, the FP should follow the appropriate precautions and insist that all members of the health care team follow suit.

CASE