User login

“I would argue that the most important reason to care about climate change is because of our children,” Saul Hymes, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually this year.

“Being able to point out to people how climate change harms the health of their children and affects their children’s risk of infections is a particularly effective argument to make,” said Dr. Hymes, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University.

Rachel Boykan, MD, a pediatrician at the university, found Dr. Hymes’ presentation excellent and highly relevant to issues all health care workers treating children face, even beyond infectious disease.

“It was data focused but also understandable for a broad audience,” Dr. Boykan, who was not involved in the presentation, said in an interview. “He explained the science of climate change in a way that all physicians, but especially pediatricians, would find relevant. I suspect if people who were listening didn’t already prioritize the issues of climate change, they certainly did after hearing the talk.”

She also appreciated that Dr. Hymes addressed how climate change affects everyone in both their professional and personal lives.

“We need to be prepared to address the clinical issues that ensue after a natural disaster, and we need to be advocates for change so that we can slow down the climate changes we are all dealing with,” said Dr. Boykan, adding that the presentation was also inspiring. “He presented many different viewpoints and many ways to be involved and to be an advocate. I would think that a good number of people who were there would be energized to do something differently to combat climate change.”

The multitudinous impacts of climate change

The impact of climate change on human health is broad and far-reaching, Dr. Hymes said. It doesn’t require much imagination to recognize that rising global temperatures can lead to prolonged extreme heat waves that can cause heat-related deaths and illnesses. But other effects can be more gradual or subtle. Changes in outdoor air quality can affect weather patterns, pollen counts, and air pollution that can increase risk of asthma, allergies, as well as acute and chronic respiratory and cardiovascular disease.

Sea level rise, more frequent and severe hurricanes, storm surges, and extreme precipitation all can lead to contaminated water and destruction of essential infrastructure. In addition to drowning and injuries from the storms themselves, these changes have mental health consequences, and can lead to gastrointestinal and other illnesses, including water-borne infectious disease. The distribution and prevalence of vector-borne diseases also will shift with changes in temperature, precipitation, and other weather patterns.

Distribution, prevalence of vector-borne diseases shift with climate change

One of the most common bacteria transmitted by vectors in the United States is Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease. Transmitted by deer ticks, Lyme disease is listed by the Environmental Protection Agency as an indicator of climate change’s impact on human health and is becoming more common every year. Cases doubled from 1990 to 2014, from 4 to 8 cases per 100,000 people.

Increases were most dramatic in the Northeast, where Lyme disease is endemic. States such as Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire all saw increases of 80-100 more cases per 100,000 people. Evidence now shows that Lyme disease is moving north as the climate warms. Toronto, for example, has seen more than a 400% increase in cases in less than a decade, from 128 cases per 100,000 people in 2009 to 700 cases per 100,000 in 2015.

“It’s a known phenomenon that climate change affects more northerly latitudes disproportionately to more than southerly latitudes,” Dr. Hymes said. He shared a 2013 study providing evidence that climate change is expanding the range of Lyme disease. Even when controlling for other confounding factors, the research found that areas being warmed proportionately more by climate change also are experiencing greater Lyme incidence. While Lyme cases declined in several Western and Deep South states, it significantly increased in nearly every Northeast state as well as Idaho, Arizona, and states in the northern Midwest near the Great Lakes.

“We find that this impact of climate change on the movement of vectors like ticks affects more than just Lyme disease,” Dr. Hymes said. Amblyomma americanum, the Lone Star tick, has historically been restricted to the southern United States but is now found further north, even up to New England. It carries bacteria that can cause multiple illnesses, including ehrlichiosis, heartland virus, and tularemia.

An alpha-gal meat allergy associated with this tick can lead to anaphylaxis about 6 hours after a person eats red meat or pork. Prevalence of this allergy, first reported in Georgia in 1989-1991, has been increasing and moving further north, and the Lone Star tick is a particularly heat-tolerant and heat-loving tick.

Climate change also affects how long during the year people are at risk. Lyme disease, for example, typically lasted from April/May to October, when ticks then hibernated during the cold weather. But the warming climate has expanded Lyme season: Local Lyme cases have begun occurring into November through January on Long Island over the past 5 years.

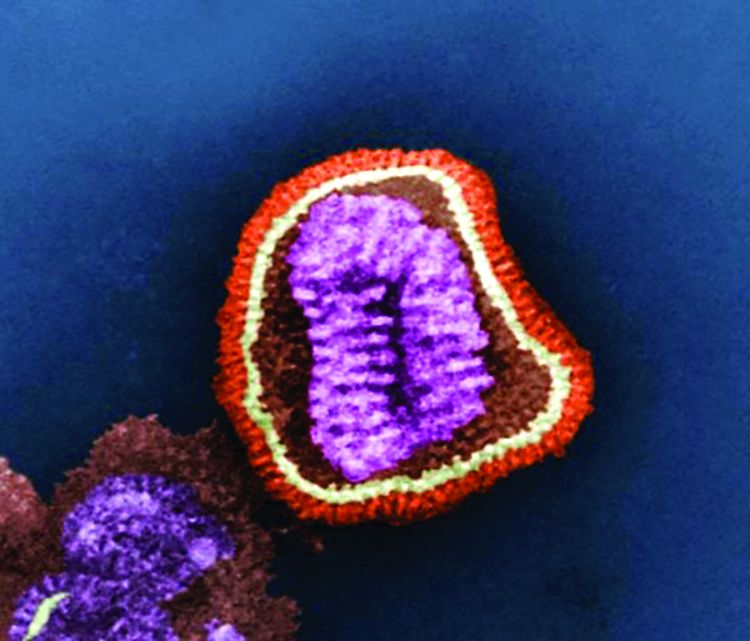

The impact of seasonal changes on infectious diseases overall is difficult to predict. The seasons for cold weather diseases such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, for example, may become shorter or milder while viruses more common in the summer, such as enteroviruses, may become a risk year-round.

Natural disasters pose multiple risks

Natural disasters can pose immediate dangers to families and have a significant impact on mental health, but that’s not their only potential impact.

“Severe weather events such as hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes are well established in the climate change literature as an effect of increased temperatures and more volatile weather systems, but they also have a significant effect on infectious diseases and on children in particular,” Dr. Hymes said. “Hurricanes and flash floods can cause increases in infectious disease outbreaks through a variety of different ways.”

They can bring saltwater, freshwater, and sometimes soil organisms into the food and water supplies, and lead to sewage contamination from overloaded sewers, overflowing storm drains, and loss of power or pumps. Displaced animal vectors, such as rats, can lead to spread of other diseases, such as plague, hantavirus, typhus, and rabies.

Examples of saltwater organisms include Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium marinum, all of which can cause infections in wounds and/or diarrheal illness or bacteremia. Similarly, organisms from freshwater and soil that can cause serious illness or death include Aeromonas, Pseudomonas, Amebiasis, Giardia, and Legionella. Without access to clean water, or with contamination from overflowing sewage, cryptosporidium, Escherichia coli, salmonella, typhoid, norovirus, hepatitis A and E, and even cholera can also become problems as well.

In Houston following Hurricane Harvey, for example, cellulitis cases doubled and included infections from organisms different from the usual suspects. Scrapes and cuts that occurred during the storm also festered sooner.

Cases of disease linked to Hurricane Katrina in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report included 6 cases of cholera, 17 cases of other vibrio – including five that resulted in death – and reported cases of norovirus, Escherichia coli, salmonella, and influenza and pneumonia from overcrowding of evacuees.

You can help in a variety of ways

You can play several key roles as the world’s climate changes, starting with preparing for the changes. You should familiarize themselves with new and emerging infections, or those that have been around a while but not seen in your areas, such as Lyme, Zika, and Dengue.

“If you haven’t seen them already, you likely will due to movements of vector-borne infections that can occur due to climate change,” Dr. Hymes said. “You also want to expect the usual common diseases, but maybe at unsuspected times,” he added. “If you have a pediatric patient who looks like they have Coxsackie virus but it’s February, if it’s been a warm February, it may very well be Coxsackie virus.”

Following natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes and tornadoes, consider who your patients are. If they’re evacuees, are they living in overcrowded conditions? Do they have access to clean water? If not, explain the need to boil water if they can, or to use iodine tablets or a portable pump filter. Consider that some infections may involve unexpected or odd organisms, such as legionella pneumonia or vibrio cellulitis, and contact your local infectious disease doctor as needed.

You also can make personal lifestyle changes that, while small, can add up in the aggregate in reducing carbon footprints, such as purchasing an electric or hybrid car and converting their homes to solar power.

“For very little money, you can purchase carbon offsets,” Dr. Hymes said, such as $10-$15 a month for wind power offsets with home electricity or $5-$10 a month for car or plane travel.

“But really, the most important thing we can do as pediatricians is educate,” Dr. Hymes said. “Taking opportunities every day in your office to educate your patients and educate your colleagues about the importance of climate change in our patients’ health and our own children’s health is super, super important.”

Dr. Hymes and Dr. Boykan had no relevant financial disclosures.

“I would argue that the most important reason to care about climate change is because of our children,” Saul Hymes, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually this year.

“Being able to point out to people how climate change harms the health of their children and affects their children’s risk of infections is a particularly effective argument to make,” said Dr. Hymes, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University.

Rachel Boykan, MD, a pediatrician at the university, found Dr. Hymes’ presentation excellent and highly relevant to issues all health care workers treating children face, even beyond infectious disease.

“It was data focused but also understandable for a broad audience,” Dr. Boykan, who was not involved in the presentation, said in an interview. “He explained the science of climate change in a way that all physicians, but especially pediatricians, would find relevant. I suspect if people who were listening didn’t already prioritize the issues of climate change, they certainly did after hearing the talk.”

She also appreciated that Dr. Hymes addressed how climate change affects everyone in both their professional and personal lives.

“We need to be prepared to address the clinical issues that ensue after a natural disaster, and we need to be advocates for change so that we can slow down the climate changes we are all dealing with,” said Dr. Boykan, adding that the presentation was also inspiring. “He presented many different viewpoints and many ways to be involved and to be an advocate. I would think that a good number of people who were there would be energized to do something differently to combat climate change.”

The multitudinous impacts of climate change

The impact of climate change on human health is broad and far-reaching, Dr. Hymes said. It doesn’t require much imagination to recognize that rising global temperatures can lead to prolonged extreme heat waves that can cause heat-related deaths and illnesses. But other effects can be more gradual or subtle. Changes in outdoor air quality can affect weather patterns, pollen counts, and air pollution that can increase risk of asthma, allergies, as well as acute and chronic respiratory and cardiovascular disease.

Sea level rise, more frequent and severe hurricanes, storm surges, and extreme precipitation all can lead to contaminated water and destruction of essential infrastructure. In addition to drowning and injuries from the storms themselves, these changes have mental health consequences, and can lead to gastrointestinal and other illnesses, including water-borne infectious disease. The distribution and prevalence of vector-borne diseases also will shift with changes in temperature, precipitation, and other weather patterns.

Distribution, prevalence of vector-borne diseases shift with climate change

One of the most common bacteria transmitted by vectors in the United States is Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease. Transmitted by deer ticks, Lyme disease is listed by the Environmental Protection Agency as an indicator of climate change’s impact on human health and is becoming more common every year. Cases doubled from 1990 to 2014, from 4 to 8 cases per 100,000 people.

Increases were most dramatic in the Northeast, where Lyme disease is endemic. States such as Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire all saw increases of 80-100 more cases per 100,000 people. Evidence now shows that Lyme disease is moving north as the climate warms. Toronto, for example, has seen more than a 400% increase in cases in less than a decade, from 128 cases per 100,000 people in 2009 to 700 cases per 100,000 in 2015.

“It’s a known phenomenon that climate change affects more northerly latitudes disproportionately to more than southerly latitudes,” Dr. Hymes said. He shared a 2013 study providing evidence that climate change is expanding the range of Lyme disease. Even when controlling for other confounding factors, the research found that areas being warmed proportionately more by climate change also are experiencing greater Lyme incidence. While Lyme cases declined in several Western and Deep South states, it significantly increased in nearly every Northeast state as well as Idaho, Arizona, and states in the northern Midwest near the Great Lakes.

“We find that this impact of climate change on the movement of vectors like ticks affects more than just Lyme disease,” Dr. Hymes said. Amblyomma americanum, the Lone Star tick, has historically been restricted to the southern United States but is now found further north, even up to New England. It carries bacteria that can cause multiple illnesses, including ehrlichiosis, heartland virus, and tularemia.

An alpha-gal meat allergy associated with this tick can lead to anaphylaxis about 6 hours after a person eats red meat or pork. Prevalence of this allergy, first reported in Georgia in 1989-1991, has been increasing and moving further north, and the Lone Star tick is a particularly heat-tolerant and heat-loving tick.

Climate change also affects how long during the year people are at risk. Lyme disease, for example, typically lasted from April/May to October, when ticks then hibernated during the cold weather. But the warming climate has expanded Lyme season: Local Lyme cases have begun occurring into November through January on Long Island over the past 5 years.

The impact of seasonal changes on infectious diseases overall is difficult to predict. The seasons for cold weather diseases such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, for example, may become shorter or milder while viruses more common in the summer, such as enteroviruses, may become a risk year-round.

Natural disasters pose multiple risks

Natural disasters can pose immediate dangers to families and have a significant impact on mental health, but that’s not their only potential impact.

“Severe weather events such as hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes are well established in the climate change literature as an effect of increased temperatures and more volatile weather systems, but they also have a significant effect on infectious diseases and on children in particular,” Dr. Hymes said. “Hurricanes and flash floods can cause increases in infectious disease outbreaks through a variety of different ways.”

They can bring saltwater, freshwater, and sometimes soil organisms into the food and water supplies, and lead to sewage contamination from overloaded sewers, overflowing storm drains, and loss of power or pumps. Displaced animal vectors, such as rats, can lead to spread of other diseases, such as plague, hantavirus, typhus, and rabies.

Examples of saltwater organisms include Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium marinum, all of which can cause infections in wounds and/or diarrheal illness or bacteremia. Similarly, organisms from freshwater and soil that can cause serious illness or death include Aeromonas, Pseudomonas, Amebiasis, Giardia, and Legionella. Without access to clean water, or with contamination from overflowing sewage, cryptosporidium, Escherichia coli, salmonella, typhoid, norovirus, hepatitis A and E, and even cholera can also become problems as well.

In Houston following Hurricane Harvey, for example, cellulitis cases doubled and included infections from organisms different from the usual suspects. Scrapes and cuts that occurred during the storm also festered sooner.

Cases of disease linked to Hurricane Katrina in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report included 6 cases of cholera, 17 cases of other vibrio – including five that resulted in death – and reported cases of norovirus, Escherichia coli, salmonella, and influenza and pneumonia from overcrowding of evacuees.

You can help in a variety of ways

You can play several key roles as the world’s climate changes, starting with preparing for the changes. You should familiarize themselves with new and emerging infections, or those that have been around a while but not seen in your areas, such as Lyme, Zika, and Dengue.

“If you haven’t seen them already, you likely will due to movements of vector-borne infections that can occur due to climate change,” Dr. Hymes said. “You also want to expect the usual common diseases, but maybe at unsuspected times,” he added. “If you have a pediatric patient who looks like they have Coxsackie virus but it’s February, if it’s been a warm February, it may very well be Coxsackie virus.”

Following natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes and tornadoes, consider who your patients are. If they’re evacuees, are they living in overcrowded conditions? Do they have access to clean water? If not, explain the need to boil water if they can, or to use iodine tablets or a portable pump filter. Consider that some infections may involve unexpected or odd organisms, such as legionella pneumonia or vibrio cellulitis, and contact your local infectious disease doctor as needed.

You also can make personal lifestyle changes that, while small, can add up in the aggregate in reducing carbon footprints, such as purchasing an electric or hybrid car and converting their homes to solar power.

“For very little money, you can purchase carbon offsets,” Dr. Hymes said, such as $10-$15 a month for wind power offsets with home electricity or $5-$10 a month for car or plane travel.

“But really, the most important thing we can do as pediatricians is educate,” Dr. Hymes said. “Taking opportunities every day in your office to educate your patients and educate your colleagues about the importance of climate change in our patients’ health and our own children’s health is super, super important.”

Dr. Hymes and Dr. Boykan had no relevant financial disclosures.

“I would argue that the most important reason to care about climate change is because of our children,” Saul Hymes, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually this year.

“Being able to point out to people how climate change harms the health of their children and affects their children’s risk of infections is a particularly effective argument to make,” said Dr. Hymes, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University.

Rachel Boykan, MD, a pediatrician at the university, found Dr. Hymes’ presentation excellent and highly relevant to issues all health care workers treating children face, even beyond infectious disease.

“It was data focused but also understandable for a broad audience,” Dr. Boykan, who was not involved in the presentation, said in an interview. “He explained the science of climate change in a way that all physicians, but especially pediatricians, would find relevant. I suspect if people who were listening didn’t already prioritize the issues of climate change, they certainly did after hearing the talk.”

She also appreciated that Dr. Hymes addressed how climate change affects everyone in both their professional and personal lives.

“We need to be prepared to address the clinical issues that ensue after a natural disaster, and we need to be advocates for change so that we can slow down the climate changes we are all dealing with,” said Dr. Boykan, adding that the presentation was also inspiring. “He presented many different viewpoints and many ways to be involved and to be an advocate. I would think that a good number of people who were there would be energized to do something differently to combat climate change.”

The multitudinous impacts of climate change

The impact of climate change on human health is broad and far-reaching, Dr. Hymes said. It doesn’t require much imagination to recognize that rising global temperatures can lead to prolonged extreme heat waves that can cause heat-related deaths and illnesses. But other effects can be more gradual or subtle. Changes in outdoor air quality can affect weather patterns, pollen counts, and air pollution that can increase risk of asthma, allergies, as well as acute and chronic respiratory and cardiovascular disease.

Sea level rise, more frequent and severe hurricanes, storm surges, and extreme precipitation all can lead to contaminated water and destruction of essential infrastructure. In addition to drowning and injuries from the storms themselves, these changes have mental health consequences, and can lead to gastrointestinal and other illnesses, including water-borne infectious disease. The distribution and prevalence of vector-borne diseases also will shift with changes in temperature, precipitation, and other weather patterns.

Distribution, prevalence of vector-borne diseases shift with climate change

One of the most common bacteria transmitted by vectors in the United States is Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease. Transmitted by deer ticks, Lyme disease is listed by the Environmental Protection Agency as an indicator of climate change’s impact on human health and is becoming more common every year. Cases doubled from 1990 to 2014, from 4 to 8 cases per 100,000 people.

Increases were most dramatic in the Northeast, where Lyme disease is endemic. States such as Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire all saw increases of 80-100 more cases per 100,000 people. Evidence now shows that Lyme disease is moving north as the climate warms. Toronto, for example, has seen more than a 400% increase in cases in less than a decade, from 128 cases per 100,000 people in 2009 to 700 cases per 100,000 in 2015.

“It’s a known phenomenon that climate change affects more northerly latitudes disproportionately to more than southerly latitudes,” Dr. Hymes said. He shared a 2013 study providing evidence that climate change is expanding the range of Lyme disease. Even when controlling for other confounding factors, the research found that areas being warmed proportionately more by climate change also are experiencing greater Lyme incidence. While Lyme cases declined in several Western and Deep South states, it significantly increased in nearly every Northeast state as well as Idaho, Arizona, and states in the northern Midwest near the Great Lakes.

“We find that this impact of climate change on the movement of vectors like ticks affects more than just Lyme disease,” Dr. Hymes said. Amblyomma americanum, the Lone Star tick, has historically been restricted to the southern United States but is now found further north, even up to New England. It carries bacteria that can cause multiple illnesses, including ehrlichiosis, heartland virus, and tularemia.

An alpha-gal meat allergy associated with this tick can lead to anaphylaxis about 6 hours after a person eats red meat or pork. Prevalence of this allergy, first reported in Georgia in 1989-1991, has been increasing and moving further north, and the Lone Star tick is a particularly heat-tolerant and heat-loving tick.

Climate change also affects how long during the year people are at risk. Lyme disease, for example, typically lasted from April/May to October, when ticks then hibernated during the cold weather. But the warming climate has expanded Lyme season: Local Lyme cases have begun occurring into November through January on Long Island over the past 5 years.

The impact of seasonal changes on infectious diseases overall is difficult to predict. The seasons for cold weather diseases such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, for example, may become shorter or milder while viruses more common in the summer, such as enteroviruses, may become a risk year-round.

Natural disasters pose multiple risks

Natural disasters can pose immediate dangers to families and have a significant impact on mental health, but that’s not their only potential impact.

“Severe weather events such as hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes are well established in the climate change literature as an effect of increased temperatures and more volatile weather systems, but they also have a significant effect on infectious diseases and on children in particular,” Dr. Hymes said. “Hurricanes and flash floods can cause increases in infectious disease outbreaks through a variety of different ways.”

They can bring saltwater, freshwater, and sometimes soil organisms into the food and water supplies, and lead to sewage contamination from overloaded sewers, overflowing storm drains, and loss of power or pumps. Displaced animal vectors, such as rats, can lead to spread of other diseases, such as plague, hantavirus, typhus, and rabies.

Examples of saltwater organisms include Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium marinum, all of which can cause infections in wounds and/or diarrheal illness or bacteremia. Similarly, organisms from freshwater and soil that can cause serious illness or death include Aeromonas, Pseudomonas, Amebiasis, Giardia, and Legionella. Without access to clean water, or with contamination from overflowing sewage, cryptosporidium, Escherichia coli, salmonella, typhoid, norovirus, hepatitis A and E, and even cholera can also become problems as well.

In Houston following Hurricane Harvey, for example, cellulitis cases doubled and included infections from organisms different from the usual suspects. Scrapes and cuts that occurred during the storm also festered sooner.

Cases of disease linked to Hurricane Katrina in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report included 6 cases of cholera, 17 cases of other vibrio – including five that resulted in death – and reported cases of norovirus, Escherichia coli, salmonella, and influenza and pneumonia from overcrowding of evacuees.

You can help in a variety of ways

You can play several key roles as the world’s climate changes, starting with preparing for the changes. You should familiarize themselves with new and emerging infections, or those that have been around a while but not seen in your areas, such as Lyme, Zika, and Dengue.

“If you haven’t seen them already, you likely will due to movements of vector-borne infections that can occur due to climate change,” Dr. Hymes said. “You also want to expect the usual common diseases, but maybe at unsuspected times,” he added. “If you have a pediatric patient who looks like they have Coxsackie virus but it’s February, if it’s been a warm February, it may very well be Coxsackie virus.”

Following natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes and tornadoes, consider who your patients are. If they’re evacuees, are they living in overcrowded conditions? Do they have access to clean water? If not, explain the need to boil water if they can, or to use iodine tablets or a portable pump filter. Consider that some infections may involve unexpected or odd organisms, such as legionella pneumonia or vibrio cellulitis, and contact your local infectious disease doctor as needed.

You also can make personal lifestyle changes that, while small, can add up in the aggregate in reducing carbon footprints, such as purchasing an electric or hybrid car and converting their homes to solar power.

“For very little money, you can purchase carbon offsets,” Dr. Hymes said, such as $10-$15 a month for wind power offsets with home electricity or $5-$10 a month for car or plane travel.

“But really, the most important thing we can do as pediatricians is educate,” Dr. Hymes said. “Taking opportunities every day in your office to educate your patients and educate your colleagues about the importance of climate change in our patients’ health and our own children’s health is super, super important.”

Dr. Hymes and Dr. Boykan had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAP 2020