User login

; the risk of stroke was moderate to high.

The trial was stopped earlier this year because of an “overwhelming” reduction in bleeding with abelacimab in comparison to rivaroxaban. Abelacimab is a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month.

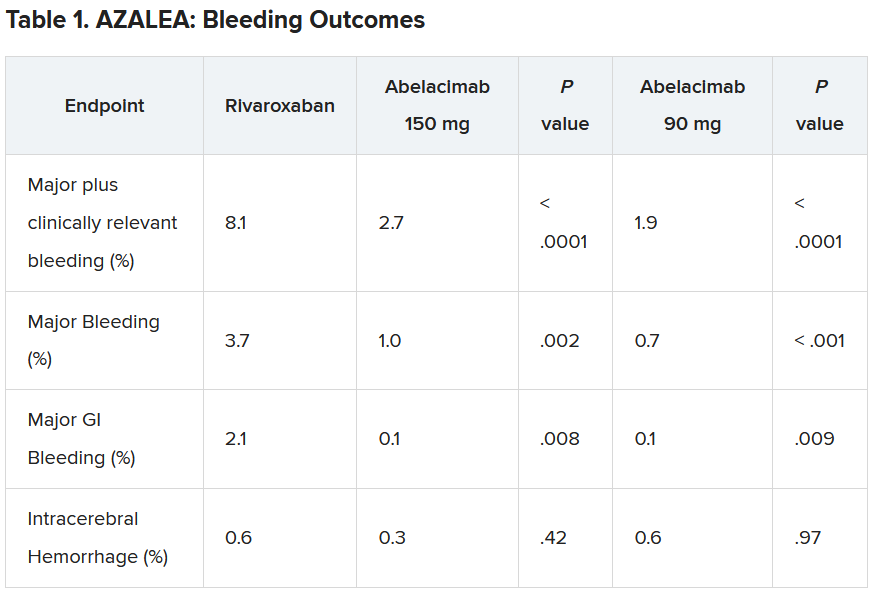

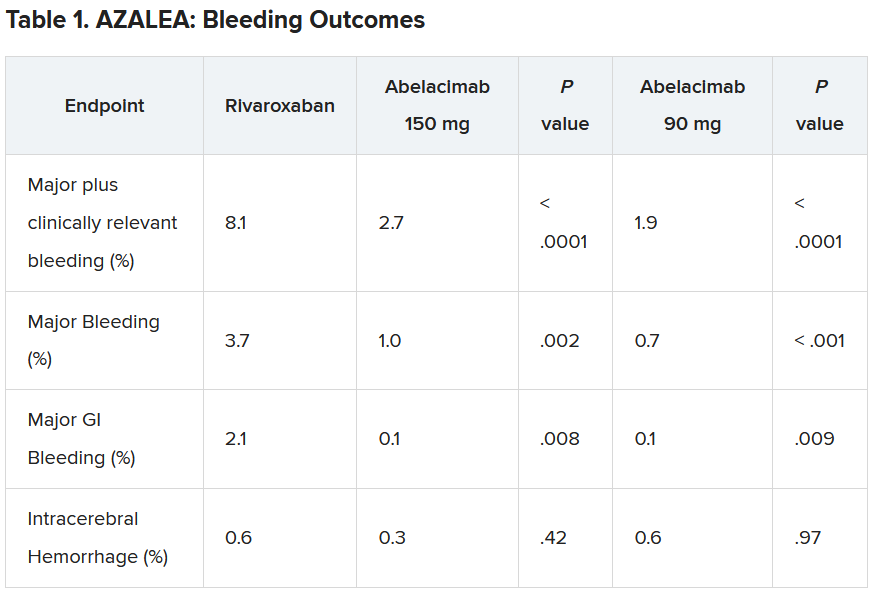

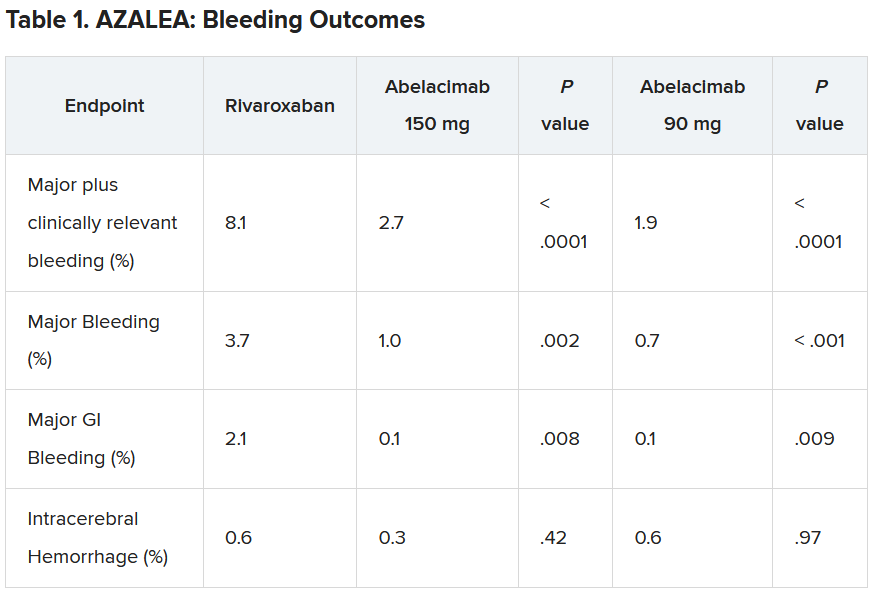

“Details of the bleeding results have now shown that the 150-mg dose of abelacimab, which is the dose being carried forward to phase 3 trials, was associated with a 67% reduction in major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, the primary endpoint of the study.”

In addition, major bleeding was reduced by 74%, and major gastrointestinal bleeding was reduced by 93%.

“We are seeing really profound reductions in bleeding with this agent vs. a NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant],” lead AZALEA investigator Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“Major bleeding – effectively the type of bleeding that results in hospitalization – is reduced by more than two-thirds, and major GI bleeding – which is the most common type of bleeding experienced by AF patients on anticoagulants – is almost eliminated. This gives us real hope that we have finally found an anticoagulant that is remarkably safe and will allow us to use anticoagulation in our most vulnerable patients,” he said.

Dr. Ruff presented the full results from the AZALEA trial at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He noted that AFib is one of the most common medical conditions in the world and that it confers an increased risk of stroke. Anticoagulants reduce this risk very effectively, and while the NOACS, such as apixaban and rivaroxaban, are safer than warfarin, significant bleeding still occurs, and “shockingly,” he said, between 30% and 60% of patients are not prescribed an anticoagulant or discontinue treatment because of bleeding concerns.

“Clearly, we need safer anticoagulants to protect these patients. Factor XI inhibitors, of which abelacimab is one, have emerged as the most promising agents, as they are thought to provide precision anticoagulation,” Dr. Ruff said.

He explained that factor XI appears to be involved in the formation of thrombus, which blocks arteries and causes strokes and myocardial infarction (thrombosis), but not in the healing process of blood vessels after injury (hemostasis). So, it is believed that inhibiting factor XI should reduce thrombotic events without causing excess bleeding.

AZALEA, which is the largest and longest trial of a factor XI inhibitor to date, enrolled 1,287 adults with AF who were at moderate to high risk of stroke.

They were randomly assigned to receive one of three treatments: oral rivaroxaban 20 mg daily; abelacimab 90 mg; or abelacimab 150 mg. Abelacimab was given monthly by injection.

Both doses of abelacimab inhibited factor XI almost completely; 97% inhibition was achieved with the 90-mg dose, and 99% inhibition was achieved with the 150-mg dose.

Results showed that after a median follow-up of 1.8 years, there was a clear reduction in all bleeding endpoints with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban.

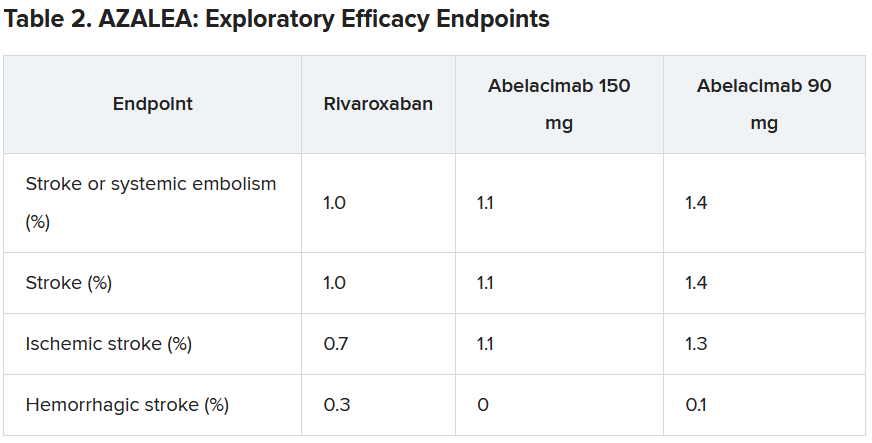

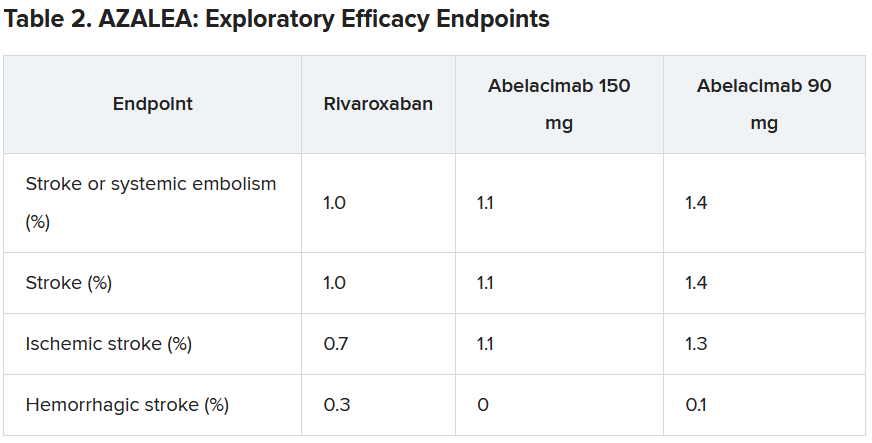

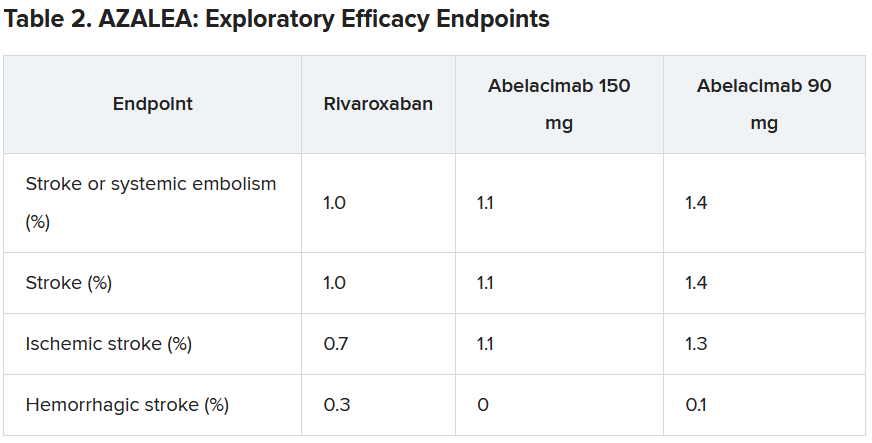

Dr. Ruff explained that the trial was powered to detect differences in bleeding, not stroke, but the investigators approached this in an exploratory way.

“As expected, the numbers were low, with just 25 strokes (23 ischemic strokes) across all three groups in the trial. So, because of this very low rate, we are really not able to compare how abelacimab compares with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke,” he commented.

He did, however, suggest that the low stroke rate in the study was encouraging.

“If we look at the same population without anticoagulation, the stroke rate would be about 7% per year. And we see here in this trial that in all three arms, the stroke rate was just above 1% per year. I think this shows that all the patients in the trial were getting highly effective anticoagulation,” he said.

“But what this trial doesn’t answer – because the numbers are so low – is exactly how effective factor XI inhibition with abelacimab is, compared to NOACs in reducing stroke rates. That requires dedicated phase 3 trials.”

Dr. Ruff pointed out that there are some reassuring data from phase 2 trials in venous thromboembolism (VTE), in which the 150-mg dose of abelacimab was associated with an 80% reduction in VTE, compared with enoxaparin. “Historically in the development of anticoagulants, efficacy in VTE has translated into efficacy in stroke prevention, so that is very encouraging,” he commented.

“So, I think our results along with the VTE results are encouraging, but the precision regarding the relative efficacy compared to NOACs is still an open question that needs to be clarified in phase 3 trials,” he concluded.

Several phase 3 trials are now underway with abelacimab and two other small-molecule orally available factor XI inhibitors, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer).

The designated discussant of the AZALEA study at the AHA meeting, Manesh Patel. MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C., described the results as “an important step forward.”

“This trial, with the prior data in this field, show that factor XI inhibition as a target is biologically possible (studies showing > 95% inhibition), significantly less bleeding than NOACS. We await the phase 3 studies, but having significantly less bleeding and similar or less stroke would be a substantial step forward for the field,” he said.

John Alexander, MD, also from Duke University, said: “There were clinically important reductions in bleeding with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban. This is consistent to what we’ve seen with comparisons between other factor XI inhibitors and other factor Xa inhibitors.”

On the exploratory efficacy results, Dr. Alexander agreed with Dr. Ruff that it was not possible to get any idea of how abelacimab compared with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke. “The hazard ratio and confidence intervals comparing abelacimab and rivaroxaban include substantial lower rates, no difference, and substantially higher rates,” he noted.

“We need to wait for the results of phase 3 trials, with abelacimab and other factor XI inhibitors, to understand how well factor XI inhibition prevents stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation,” Dr. Alexander added. “These trials are ongoing.”

Dr. Ruff concluded: “Assuming the data from ongoing phase 3 trials confirm the benefit of factor XI inhibitors for stroke prevention in people with AF, it will really be transformative for the field of cardiology.

“Our first mission in treating people with AF is to prevent stroke, and our ability to do this with a remarkably safe anticoagulant such as abelacimab would be an incredible advance,” he concluded.

Dr. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AF executive committee for BMS/Janssen (milvexian), and has been on an advisory board for Bayer (asundexian). Dr. Patel has received grants from and acts as an advisor to Bayer and Janssen. Dr. Alexander receives research funding from Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

; the risk of stroke was moderate to high.

The trial was stopped earlier this year because of an “overwhelming” reduction in bleeding with abelacimab in comparison to rivaroxaban. Abelacimab is a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month.

“Details of the bleeding results have now shown that the 150-mg dose of abelacimab, which is the dose being carried forward to phase 3 trials, was associated with a 67% reduction in major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, the primary endpoint of the study.”

In addition, major bleeding was reduced by 74%, and major gastrointestinal bleeding was reduced by 93%.

“We are seeing really profound reductions in bleeding with this agent vs. a NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant],” lead AZALEA investigator Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“Major bleeding – effectively the type of bleeding that results in hospitalization – is reduced by more than two-thirds, and major GI bleeding – which is the most common type of bleeding experienced by AF patients on anticoagulants – is almost eliminated. This gives us real hope that we have finally found an anticoagulant that is remarkably safe and will allow us to use anticoagulation in our most vulnerable patients,” he said.

Dr. Ruff presented the full results from the AZALEA trial at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He noted that AFib is one of the most common medical conditions in the world and that it confers an increased risk of stroke. Anticoagulants reduce this risk very effectively, and while the NOACS, such as apixaban and rivaroxaban, are safer than warfarin, significant bleeding still occurs, and “shockingly,” he said, between 30% and 60% of patients are not prescribed an anticoagulant or discontinue treatment because of bleeding concerns.

“Clearly, we need safer anticoagulants to protect these patients. Factor XI inhibitors, of which abelacimab is one, have emerged as the most promising agents, as they are thought to provide precision anticoagulation,” Dr. Ruff said.

He explained that factor XI appears to be involved in the formation of thrombus, which blocks arteries and causes strokes and myocardial infarction (thrombosis), but not in the healing process of blood vessels after injury (hemostasis). So, it is believed that inhibiting factor XI should reduce thrombotic events without causing excess bleeding.

AZALEA, which is the largest and longest trial of a factor XI inhibitor to date, enrolled 1,287 adults with AF who were at moderate to high risk of stroke.

They were randomly assigned to receive one of three treatments: oral rivaroxaban 20 mg daily; abelacimab 90 mg; or abelacimab 150 mg. Abelacimab was given monthly by injection.

Both doses of abelacimab inhibited factor XI almost completely; 97% inhibition was achieved with the 90-mg dose, and 99% inhibition was achieved with the 150-mg dose.

Results showed that after a median follow-up of 1.8 years, there was a clear reduction in all bleeding endpoints with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban.

Dr. Ruff explained that the trial was powered to detect differences in bleeding, not stroke, but the investigators approached this in an exploratory way.

“As expected, the numbers were low, with just 25 strokes (23 ischemic strokes) across all three groups in the trial. So, because of this very low rate, we are really not able to compare how abelacimab compares with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke,” he commented.

He did, however, suggest that the low stroke rate in the study was encouraging.

“If we look at the same population without anticoagulation, the stroke rate would be about 7% per year. And we see here in this trial that in all three arms, the stroke rate was just above 1% per year. I think this shows that all the patients in the trial were getting highly effective anticoagulation,” he said.

“But what this trial doesn’t answer – because the numbers are so low – is exactly how effective factor XI inhibition with abelacimab is, compared to NOACs in reducing stroke rates. That requires dedicated phase 3 trials.”

Dr. Ruff pointed out that there are some reassuring data from phase 2 trials in venous thromboembolism (VTE), in which the 150-mg dose of abelacimab was associated with an 80% reduction in VTE, compared with enoxaparin. “Historically in the development of anticoagulants, efficacy in VTE has translated into efficacy in stroke prevention, so that is very encouraging,” he commented.

“So, I think our results along with the VTE results are encouraging, but the precision regarding the relative efficacy compared to NOACs is still an open question that needs to be clarified in phase 3 trials,” he concluded.

Several phase 3 trials are now underway with abelacimab and two other small-molecule orally available factor XI inhibitors, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer).

The designated discussant of the AZALEA study at the AHA meeting, Manesh Patel. MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C., described the results as “an important step forward.”

“This trial, with the prior data in this field, show that factor XI inhibition as a target is biologically possible (studies showing > 95% inhibition), significantly less bleeding than NOACS. We await the phase 3 studies, but having significantly less bleeding and similar or less stroke would be a substantial step forward for the field,” he said.

John Alexander, MD, also from Duke University, said: “There were clinically important reductions in bleeding with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban. This is consistent to what we’ve seen with comparisons between other factor XI inhibitors and other factor Xa inhibitors.”

On the exploratory efficacy results, Dr. Alexander agreed with Dr. Ruff that it was not possible to get any idea of how abelacimab compared with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke. “The hazard ratio and confidence intervals comparing abelacimab and rivaroxaban include substantial lower rates, no difference, and substantially higher rates,” he noted.

“We need to wait for the results of phase 3 trials, with abelacimab and other factor XI inhibitors, to understand how well factor XI inhibition prevents stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation,” Dr. Alexander added. “These trials are ongoing.”

Dr. Ruff concluded: “Assuming the data from ongoing phase 3 trials confirm the benefit of factor XI inhibitors for stroke prevention in people with AF, it will really be transformative for the field of cardiology.

“Our first mission in treating people with AF is to prevent stroke, and our ability to do this with a remarkably safe anticoagulant such as abelacimab would be an incredible advance,” he concluded.

Dr. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AF executive committee for BMS/Janssen (milvexian), and has been on an advisory board for Bayer (asundexian). Dr. Patel has received grants from and acts as an advisor to Bayer and Janssen. Dr. Alexander receives research funding from Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

; the risk of stroke was moderate to high.

The trial was stopped earlier this year because of an “overwhelming” reduction in bleeding with abelacimab in comparison to rivaroxaban. Abelacimab is a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month.

“Details of the bleeding results have now shown that the 150-mg dose of abelacimab, which is the dose being carried forward to phase 3 trials, was associated with a 67% reduction in major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, the primary endpoint of the study.”

In addition, major bleeding was reduced by 74%, and major gastrointestinal bleeding was reduced by 93%.

“We are seeing really profound reductions in bleeding with this agent vs. a NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant],” lead AZALEA investigator Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“Major bleeding – effectively the type of bleeding that results in hospitalization – is reduced by more than two-thirds, and major GI bleeding – which is the most common type of bleeding experienced by AF patients on anticoagulants – is almost eliminated. This gives us real hope that we have finally found an anticoagulant that is remarkably safe and will allow us to use anticoagulation in our most vulnerable patients,” he said.

Dr. Ruff presented the full results from the AZALEA trial at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He noted that AFib is one of the most common medical conditions in the world and that it confers an increased risk of stroke. Anticoagulants reduce this risk very effectively, and while the NOACS, such as apixaban and rivaroxaban, are safer than warfarin, significant bleeding still occurs, and “shockingly,” he said, between 30% and 60% of patients are not prescribed an anticoagulant or discontinue treatment because of bleeding concerns.

“Clearly, we need safer anticoagulants to protect these patients. Factor XI inhibitors, of which abelacimab is one, have emerged as the most promising agents, as they are thought to provide precision anticoagulation,” Dr. Ruff said.

He explained that factor XI appears to be involved in the formation of thrombus, which blocks arteries and causes strokes and myocardial infarction (thrombosis), but not in the healing process of blood vessels after injury (hemostasis). So, it is believed that inhibiting factor XI should reduce thrombotic events without causing excess bleeding.

AZALEA, which is the largest and longest trial of a factor XI inhibitor to date, enrolled 1,287 adults with AF who were at moderate to high risk of stroke.

They were randomly assigned to receive one of three treatments: oral rivaroxaban 20 mg daily; abelacimab 90 mg; or abelacimab 150 mg. Abelacimab was given monthly by injection.

Both doses of abelacimab inhibited factor XI almost completely; 97% inhibition was achieved with the 90-mg dose, and 99% inhibition was achieved with the 150-mg dose.

Results showed that after a median follow-up of 1.8 years, there was a clear reduction in all bleeding endpoints with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban.

Dr. Ruff explained that the trial was powered to detect differences in bleeding, not stroke, but the investigators approached this in an exploratory way.

“As expected, the numbers were low, with just 25 strokes (23 ischemic strokes) across all three groups in the trial. So, because of this very low rate, we are really not able to compare how abelacimab compares with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke,” he commented.

He did, however, suggest that the low stroke rate in the study was encouraging.

“If we look at the same population without anticoagulation, the stroke rate would be about 7% per year. And we see here in this trial that in all three arms, the stroke rate was just above 1% per year. I think this shows that all the patients in the trial were getting highly effective anticoagulation,” he said.

“But what this trial doesn’t answer – because the numbers are so low – is exactly how effective factor XI inhibition with abelacimab is, compared to NOACs in reducing stroke rates. That requires dedicated phase 3 trials.”

Dr. Ruff pointed out that there are some reassuring data from phase 2 trials in venous thromboembolism (VTE), in which the 150-mg dose of abelacimab was associated with an 80% reduction in VTE, compared with enoxaparin. “Historically in the development of anticoagulants, efficacy in VTE has translated into efficacy in stroke prevention, so that is very encouraging,” he commented.

“So, I think our results along with the VTE results are encouraging, but the precision regarding the relative efficacy compared to NOACs is still an open question that needs to be clarified in phase 3 trials,” he concluded.

Several phase 3 trials are now underway with abelacimab and two other small-molecule orally available factor XI inhibitors, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer).

The designated discussant of the AZALEA study at the AHA meeting, Manesh Patel. MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C., described the results as “an important step forward.”

“This trial, with the prior data in this field, show that factor XI inhibition as a target is biologically possible (studies showing > 95% inhibition), significantly less bleeding than NOACS. We await the phase 3 studies, but having significantly less bleeding and similar or less stroke would be a substantial step forward for the field,” he said.

John Alexander, MD, also from Duke University, said: “There were clinically important reductions in bleeding with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban. This is consistent to what we’ve seen with comparisons between other factor XI inhibitors and other factor Xa inhibitors.”

On the exploratory efficacy results, Dr. Alexander agreed with Dr. Ruff that it was not possible to get any idea of how abelacimab compared with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke. “The hazard ratio and confidence intervals comparing abelacimab and rivaroxaban include substantial lower rates, no difference, and substantially higher rates,” he noted.

“We need to wait for the results of phase 3 trials, with abelacimab and other factor XI inhibitors, to understand how well factor XI inhibition prevents stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation,” Dr. Alexander added. “These trials are ongoing.”

Dr. Ruff concluded: “Assuming the data from ongoing phase 3 trials confirm the benefit of factor XI inhibitors for stroke prevention in people with AF, it will really be transformative for the field of cardiology.

“Our first mission in treating people with AF is to prevent stroke, and our ability to do this with a remarkably safe anticoagulant such as abelacimab would be an incredible advance,” he concluded.

Dr. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AF executive committee for BMS/Janssen (milvexian), and has been on an advisory board for Bayer (asundexian). Dr. Patel has received grants from and acts as an advisor to Bayer and Janssen. Dr. Alexander receives research funding from Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHA 2023