User login

Elder abuse represents a mounting and alarming national health problem that is likely to continue to grow as the older adult population in the U.S. increases from 35 to 72 million by 2030.1 Elder abuse was first described in the 1970s with colloquialisms such as “granny battering” or “elder mistreatment.”2

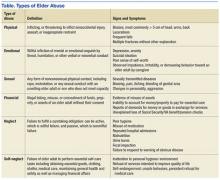

The National Research Council defines elder abuse as “intentional actions that cause harm or a serious risk of harm to an older adult by a caregiver or other person who stands in a trust relationship to the elder, or failure by a caregiver to satisfy the elders’ basic needs or to protect the elder from harm.”3 Elder abuse can further be differentiated into 6 types of abuse: physical, emotional, sexual, financial, neglect, and self-neglect (Table).

According to a National Research Council panel, an estimated 1 to 2 million Americans aged ≥ 65 years have been injured, exploited, or otherwise mistreated by someone on whom they depend on for care or protection.4 For each reported case of elder abuse, 5 more cases go unreported.5 Neglect is the most common type of abuse, followed closely by financial exploitation. Studies suggest that those aged > 80 years are 2 to 3 times more at risk for being abused compared with individuals aged between 65 and 80 years.5 Ninety percent of elder abuse occurs at the hands of perpetrators known to the victim, including 33% by adult children, 22% by other family members, and 11% by spouses or intimate partners.5 More than half, or 53%, of alleged perpetrators of elder abuse are female, and older women are 2 times more likely than men to be abused.6 Nevertheless, it should be noted that one-third of all cases of abuse occur to men, which contradicts myths that they are seldom at risk.

Recent data show that elder abuse also is detrimental to social, law, and health systems.7 Victims of elder abuse have decreased access to support systems and fewer physical, psychological, and economic reserves.7 As a result, the impact of a single incidence of elder abuse is magnified: Victims have a higher 10-year mortality and morbidity than that of older adults who have not been abused, they have significantly higher emergency department (ED) utilization and higher hospitalization rates, and they face an increased risk for institutionalization.7,8 Economic estimates suggest that cases of elder abuse contribute to more than $5.3 billion to the annual health care expenditure in the U.S.9

On the micro level, a busy clinician who sees between 20 to 40 patients daily could encounter at least 1 victim of elder abuse per day.10 Nevertheless, a national Adult Protective Services (APS) survey recently suggested that health care professionals (HCPs) were responsible for submitting 11.1% of all elder abuse reports—with physicians accounting for only 1% of reported cases.7 Several factors may help explain the reasons that so few physicians report elder abuse, including a lack of sufficient knowledge on elder abuse definitions, types, risk factors, signs and symptoms; a misunderstanding of the reporting process; or an unwillingness to get involved. A 2005 survey of almost 400 family and internal medicine physicians showed that 63% had never asked their patients about elder abuse, 98% said there should be more education on elder abuse, and 80% felt they had not been trained to diagnose elder abuse.11

Elder Abuse Legislation

The Elder Justice Act was enacted as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in March 2010 and marked the first piece of federal legislation passed to authorize federal funds to address elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation. An Elder Justice Coordinating Counsel and an advisory board were established as national leadership in the HHS. Under this leadership and support of HHS Assistant Secretary for Aging Kathy Greenlee, an Elder Justice Interagency Working Group (EJWG) was formed in 2012 to further explore the national problem of elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation. The EJWG developed an elder abuse roadmap to provide a detailed, practical guide for teams, communities, states, and national entities, fostering a coordinated approach to reduce elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation.12

The roadmap includes initiatives such as the development of an interactive, online curriculum for legal aid and civil attorneys to identify and respond to elder abuse, what lawyers need to know about elder abuse by the Department of Justice, and the development of a voluntary national APS data system to collect national data on elder abuse by the HHS. Also there has been private stakeholder action by the Archstone Foundation/Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, which is developing a national training initiative, and the Harry and Jeannette Weinberg Center for Elder Abuse Prevention at the Hebrew Home at Riverdale in New York, which is working on the development of emergency shelters for elder abuse victims.12 The 2015 White House Conference on Aging also has made elder justice one of its 4 tracks that aims to support the “dignity, independence, and quality of life of older Americans at a time when we’re seeing a huge surge in the number of older adults.”13

VHA Response to Elder Abuse

The VHA is the largest integrated, federally funded health care system in the U.S.14 The VA census estimates that about 13 million veterans and their single surviving spouses are aged ≥ 65 years, representing about one-third of the total senior population and 45.3% of the total veteran population.15 This number is expected to rise as the 7 million Vietnam-era veterans age.15

A 2000 comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use showed that the VA patient population had poorer health status, more medical conditions, and higher medical resource utilization, including more physician visits per year, more hospital admissions per year, and more days spent in the hospital per year compared with that of the general patient population.16 Another study determined that older veterans had higher rates of lifetime trauma exposure (85%) and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology secondary to combat and war zone-related exposure (53%).17Elderly veterans also may be eligible for a wide variety of VA benefits, such as disability compensation and pension, which might place them at a higher risk for financial exploitation.18 Additionally, VA programs such as Aid & Attendance or housebound benefits award additional monies to veterans who are eligible for or are receiving a VA pension.18 General knowledge of this may negatively impact older veterans. A 2010 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report revealed that guardians stole or otherwise improperly obtained $5.4 million in assets from 158 incapacitated victims, many of whom were older adults.19

From this composite, the veteran population is at particular risk for elder abuse due to high levels of physical and psychiatric vulnerability, frailty, substance use, and caregiver dependence.

VA Policy

Elder abuse in the VA health care system is governed by VA Directive 2012-022: Reporting Cases of Abuse and Neglect, which states that as a matter of policy, all VAMCs, VA outpatient clinics, vet centers, VA community living centers, home- based primary care, home- and community-based programs, state veterans homes, and community-based outpatient clinics must comply with their state laws for reporting abuse and neglect. Specifically, relevant state statutes must be followed for the “identification, evaluation, treatment, referral, and/or mandated reporting of possible victims of physical assault, rape or sexual molestation, abuse and/or neglect of elders, spouses, partners, and children.” Each VAMC director is required to ensure that policies and procedures addressing the identification, evaluation, treatment, referral and mandatory reporting of abuse and/or neglect are in compliance with the applicable state laws.

Under this policy, any VA HCP suspecting abuse, neglect, or exploitation of an individual is responsible for providing an examination and treatment to the veteran as well as making a report to the designated state agency and documenting confirmation of the report in the electronic health record of the veteran. VA HCPs are expected to make a referral for a comprehensive social work assessment conducted by a VA social worker that includes identification of problems and determination if the veteran needs to be removed from danger. Disposition planning is an integral part of this assessment and should include the possibility of provision of additional services for veterans and their caregivers and/or possible placement in an institutional setting. Likewise, care should be taken to avoid overdiagnosis or wrongful diagnosis.

In addition, the VA Social Work Program Office has implemented standardized national social work case management documentation requirements to be used by all VA social workers assigned within patient aligned care teams (PACTs) in Primary Care. Preliminary data captured by VA social workers who completed the national standardized electronic progress notes indicate there were about 3,700 veterans during fiscal year 2014 who were assessed by the social worker with a presenting issue of “Abuse and/or Neglect.” Further study is needed to better understand the demographics, psychosocial, and medical needs of this group.

VA Research and Elder Abuse

The prevalence of elder abuse among veterans is not currently known. The 2010 GAO report stated that although it could not be determined whether allegations of abuse were widespread, hundreds of allegations of physical abuse, neglect, and financial exploitation between 1990 and 2010 were noted.19 A 2006 study that examined the prevalence, types, and intervention outcomes of elder abuse cases among a sample of veterans noted that 5.4% of evaluated veterans had a case reported on their behalf.20 Recent unpublished findings from chart reviews of all cases of elder abuse reported by the Providence and Durham VAMCs to their state’s respective APS agencies between 2006 and 2012 showed 55 reported cases at the 2 institutions during the 7-year study period. Compared with national data on elder abuse prevalence, this finding suggests a significant underreporting of elder abuse within the VA health care system. These findings are likely concordant with the lack of reporting in the community. Nevertheless, VA research on elder abuse is scant and represents an important future research priority.

Conclusion

Elder abuse has long been a taboo topic. At present there is a sense of urgency to elevate elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation as a national concern and a priority for HCPs both within the VA health care system and community. Awareness of elder abuse and neglect needs to be highlighted in order for recognition and prompt intervention to follow. Interventions should include joint federal efforts to raise public awareness of the signs of elder abuse, steps to take, and how to intervene as concerned citizen. Bridges need to be connected between health care systems and community resources, utilizing social media and educational interventions. There also is a need for parallel campaigns geared to HCPs to ensure that veterans are being screened and elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation are being appropriately diagnosed and victims cared for.

Caregiver stress and burden also needs to be considered as elder abuse and neglect are not always intentional, and as we have seen with the research already done at the VA, most elder abuse cases can be resolved by swift recognition and timely addition of services in the home in lieu of institutionalization. Discussions on elder abuse should not be feared. Rather, these conversations between citizens as well as HCPs and their clients can be viewed as a point of advocacy for older adults. More specifically, identification of elder abuse can be improved with the implementation of elder abuse screening tools and development of a new tool to help identify at-risk veterans before abuse even occurs.

Prevention can be achieved with increased education to raise awareness of elder abuse. Treatment of elder abuse should include the development of a standard operating procedure on elder abuse, collaboration between state and local officials, such as department of elderly affairs or adult protective services, utilization of medical foster homes, increased accessibility to home-based primary care and respite services as well as the development of shelter beds in VA-associated nursing homes for victims of elder abuse.

Last, additional research is needed to better understand the prevalence of elder abuse among veterans, identify those who are most at risk within the veteran population, and inform the development of evidence-based interventions. As the number of older adults grows, the need for programs and services is critical to ensure protection and support of this vulnerable group within society.

1. Policastro C, Payne B. Assessing the level of elder abuse knowledge preprofessionals possess: implications for the further development of university curriculum. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2014;26(1):12-30.

2. Gorbien MJ, Eisenstein AR. Elder abuse and neglect: an overview. Clin Geriatr Med. 2005;21(2):279-292

3. National Research Council (US) Panel to Review Risk and Prevalence of Elder Abuse and Neglect; Bonnie R, Wallace R, eds. In: Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation in an Aging America. 1st ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003.

4. Wagenaar D, Rosenbaum R, Herman S, Page C. Elder abuse education in primary care residency programs: a cluster group analysis. Fam Med. 2009;41(7):481-486.

5. National Center on Elder Abuse. The national elder abuse incidence study: final report. Administration for Community Living website. http://aoa.gov/AoA_Programs/Elder_Rights/Elder_Abuse/docs/ABuseReport_Full.pdf. Published September 1998. Accessed July 11, 2016.

6. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Half of violent victimizations of the elderly in Michigan from 2005-2009 involved serious acts of violence. Bureau of Justice Statistics website. www.bjs.gov/content/pub/press/vcerlem0509pr.cfm. Accessed July 18, 2016.

7. Mosqueda L, Dong X. Elder abuse and neglect, “I don’t care anything about going to the doctor, to be honest…” JAMA. 2011;306(5):532-540.

8. Dong X, Simon MA. Elder abuse as a risk factor for hospitalization in older persons. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):911-917.

9. Choo WY, Hairi NN, Othman S, Francis DP, Baker PRA. Interventions for preventing abuse in the elderly (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CDO10321.

10. Halphen JM, Varas GM, Sadowsky JM. Recognizing and reporting elder abuse and neglect. Geriatrics. 2009;64(7):13-18.

11. Kennedy RD. Elder abuse and neglect: the experience, knowledge, and attitudes of primary care physicians. Fam Med. 2005;37(7):481-485.

12. National Center on Elder Abuse. The elder justice roadmap: a stakeholder initiative to respond to an emerging health, justice, financial and social crisis. National Center on Elder Abuse website. http://ncea.acl.gov/library/gov_report/docs/ejrp_roadmap.pdf. Accessed July 18 2016.

13. 2015 White House Conference on Aging. (WHCOA). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. http://www.whitehouseconferenceonaging.gov/2015-WHCOA-Final-Report.pdf. Accessed on July 15 2016.

14. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs website. http://www.va.gov/about_va/vahistory.asp. Updated August 20, 2015. Accessed July 18 2016.

15. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National center for veterans analysis and statistics, Veteran population. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp.Updated April 15, 2016. Accessed July 18 2016.

16. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at veterans affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257.

17. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Posttraumatic stress symptoms among older adults: a review. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treatment/older/ptsd_symptoms_older_adults.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed July 18, 2016.

18. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans: elderly veterans. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.benefits.va.gov/persona/veteran-elderly.asp. Updated October 22, 2013. Accessed July 18, 2016.

19. United States Government Accountability Office. Guardianships: Cases of Financial Exploitation, Neglect, and Abuse of Seniors. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. GAO-10-10460.

20. Moon A, Lawson K, Carpiac M, Spaziano E. Elder Abuse and neglect among veterans in Greater Los Angeles: prevalence, types, and interventional outcomes. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2006;46(3-4):187-204.

Elder abuse represents a mounting and alarming national health problem that is likely to continue to grow as the older adult population in the U.S. increases from 35 to 72 million by 2030.1 Elder abuse was first described in the 1970s with colloquialisms such as “granny battering” or “elder mistreatment.”2

The National Research Council defines elder abuse as “intentional actions that cause harm or a serious risk of harm to an older adult by a caregiver or other person who stands in a trust relationship to the elder, or failure by a caregiver to satisfy the elders’ basic needs or to protect the elder from harm.”3 Elder abuse can further be differentiated into 6 types of abuse: physical, emotional, sexual, financial, neglect, and self-neglect (Table).

According to a National Research Council panel, an estimated 1 to 2 million Americans aged ≥ 65 years have been injured, exploited, or otherwise mistreated by someone on whom they depend on for care or protection.4 For each reported case of elder abuse, 5 more cases go unreported.5 Neglect is the most common type of abuse, followed closely by financial exploitation. Studies suggest that those aged > 80 years are 2 to 3 times more at risk for being abused compared with individuals aged between 65 and 80 years.5 Ninety percent of elder abuse occurs at the hands of perpetrators known to the victim, including 33% by adult children, 22% by other family members, and 11% by spouses or intimate partners.5 More than half, or 53%, of alleged perpetrators of elder abuse are female, and older women are 2 times more likely than men to be abused.6 Nevertheless, it should be noted that one-third of all cases of abuse occur to men, which contradicts myths that they are seldom at risk.

Recent data show that elder abuse also is detrimental to social, law, and health systems.7 Victims of elder abuse have decreased access to support systems and fewer physical, psychological, and economic reserves.7 As a result, the impact of a single incidence of elder abuse is magnified: Victims have a higher 10-year mortality and morbidity than that of older adults who have not been abused, they have significantly higher emergency department (ED) utilization and higher hospitalization rates, and they face an increased risk for institutionalization.7,8 Economic estimates suggest that cases of elder abuse contribute to more than $5.3 billion to the annual health care expenditure in the U.S.9

On the micro level, a busy clinician who sees between 20 to 40 patients daily could encounter at least 1 victim of elder abuse per day.10 Nevertheless, a national Adult Protective Services (APS) survey recently suggested that health care professionals (HCPs) were responsible for submitting 11.1% of all elder abuse reports—with physicians accounting for only 1% of reported cases.7 Several factors may help explain the reasons that so few physicians report elder abuse, including a lack of sufficient knowledge on elder abuse definitions, types, risk factors, signs and symptoms; a misunderstanding of the reporting process; or an unwillingness to get involved. A 2005 survey of almost 400 family and internal medicine physicians showed that 63% had never asked their patients about elder abuse, 98% said there should be more education on elder abuse, and 80% felt they had not been trained to diagnose elder abuse.11

Elder Abuse Legislation

The Elder Justice Act was enacted as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in March 2010 and marked the first piece of federal legislation passed to authorize federal funds to address elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation. An Elder Justice Coordinating Counsel and an advisory board were established as national leadership in the HHS. Under this leadership and support of HHS Assistant Secretary for Aging Kathy Greenlee, an Elder Justice Interagency Working Group (EJWG) was formed in 2012 to further explore the national problem of elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation. The EJWG developed an elder abuse roadmap to provide a detailed, practical guide for teams, communities, states, and national entities, fostering a coordinated approach to reduce elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation.12

The roadmap includes initiatives such as the development of an interactive, online curriculum for legal aid and civil attorneys to identify and respond to elder abuse, what lawyers need to know about elder abuse by the Department of Justice, and the development of a voluntary national APS data system to collect national data on elder abuse by the HHS. Also there has been private stakeholder action by the Archstone Foundation/Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, which is developing a national training initiative, and the Harry and Jeannette Weinberg Center for Elder Abuse Prevention at the Hebrew Home at Riverdale in New York, which is working on the development of emergency shelters for elder abuse victims.12 The 2015 White House Conference on Aging also has made elder justice one of its 4 tracks that aims to support the “dignity, independence, and quality of life of older Americans at a time when we’re seeing a huge surge in the number of older adults.”13

VHA Response to Elder Abuse

The VHA is the largest integrated, federally funded health care system in the U.S.14 The VA census estimates that about 13 million veterans and their single surviving spouses are aged ≥ 65 years, representing about one-third of the total senior population and 45.3% of the total veteran population.15 This number is expected to rise as the 7 million Vietnam-era veterans age.15

A 2000 comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use showed that the VA patient population had poorer health status, more medical conditions, and higher medical resource utilization, including more physician visits per year, more hospital admissions per year, and more days spent in the hospital per year compared with that of the general patient population.16 Another study determined that older veterans had higher rates of lifetime trauma exposure (85%) and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology secondary to combat and war zone-related exposure (53%).17Elderly veterans also may be eligible for a wide variety of VA benefits, such as disability compensation and pension, which might place them at a higher risk for financial exploitation.18 Additionally, VA programs such as Aid & Attendance or housebound benefits award additional monies to veterans who are eligible for or are receiving a VA pension.18 General knowledge of this may negatively impact older veterans. A 2010 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report revealed that guardians stole or otherwise improperly obtained $5.4 million in assets from 158 incapacitated victims, many of whom were older adults.19

From this composite, the veteran population is at particular risk for elder abuse due to high levels of physical and psychiatric vulnerability, frailty, substance use, and caregiver dependence.

VA Policy

Elder abuse in the VA health care system is governed by VA Directive 2012-022: Reporting Cases of Abuse and Neglect, which states that as a matter of policy, all VAMCs, VA outpatient clinics, vet centers, VA community living centers, home- based primary care, home- and community-based programs, state veterans homes, and community-based outpatient clinics must comply with their state laws for reporting abuse and neglect. Specifically, relevant state statutes must be followed for the “identification, evaluation, treatment, referral, and/or mandated reporting of possible victims of physical assault, rape or sexual molestation, abuse and/or neglect of elders, spouses, partners, and children.” Each VAMC director is required to ensure that policies and procedures addressing the identification, evaluation, treatment, referral and mandatory reporting of abuse and/or neglect are in compliance with the applicable state laws.

Under this policy, any VA HCP suspecting abuse, neglect, or exploitation of an individual is responsible for providing an examination and treatment to the veteran as well as making a report to the designated state agency and documenting confirmation of the report in the electronic health record of the veteran. VA HCPs are expected to make a referral for a comprehensive social work assessment conducted by a VA social worker that includes identification of problems and determination if the veteran needs to be removed from danger. Disposition planning is an integral part of this assessment and should include the possibility of provision of additional services for veterans and their caregivers and/or possible placement in an institutional setting. Likewise, care should be taken to avoid overdiagnosis or wrongful diagnosis.

In addition, the VA Social Work Program Office has implemented standardized national social work case management documentation requirements to be used by all VA social workers assigned within patient aligned care teams (PACTs) in Primary Care. Preliminary data captured by VA social workers who completed the national standardized electronic progress notes indicate there were about 3,700 veterans during fiscal year 2014 who were assessed by the social worker with a presenting issue of “Abuse and/or Neglect.” Further study is needed to better understand the demographics, psychosocial, and medical needs of this group.

VA Research and Elder Abuse

The prevalence of elder abuse among veterans is not currently known. The 2010 GAO report stated that although it could not be determined whether allegations of abuse were widespread, hundreds of allegations of physical abuse, neglect, and financial exploitation between 1990 and 2010 were noted.19 A 2006 study that examined the prevalence, types, and intervention outcomes of elder abuse cases among a sample of veterans noted that 5.4% of evaluated veterans had a case reported on their behalf.20 Recent unpublished findings from chart reviews of all cases of elder abuse reported by the Providence and Durham VAMCs to their state’s respective APS agencies between 2006 and 2012 showed 55 reported cases at the 2 institutions during the 7-year study period. Compared with national data on elder abuse prevalence, this finding suggests a significant underreporting of elder abuse within the VA health care system. These findings are likely concordant with the lack of reporting in the community. Nevertheless, VA research on elder abuse is scant and represents an important future research priority.

Conclusion

Elder abuse has long been a taboo topic. At present there is a sense of urgency to elevate elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation as a national concern and a priority for HCPs both within the VA health care system and community. Awareness of elder abuse and neglect needs to be highlighted in order for recognition and prompt intervention to follow. Interventions should include joint federal efforts to raise public awareness of the signs of elder abuse, steps to take, and how to intervene as concerned citizen. Bridges need to be connected between health care systems and community resources, utilizing social media and educational interventions. There also is a need for parallel campaigns geared to HCPs to ensure that veterans are being screened and elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation are being appropriately diagnosed and victims cared for.

Caregiver stress and burden also needs to be considered as elder abuse and neglect are not always intentional, and as we have seen with the research already done at the VA, most elder abuse cases can be resolved by swift recognition and timely addition of services in the home in lieu of institutionalization. Discussions on elder abuse should not be feared. Rather, these conversations between citizens as well as HCPs and their clients can be viewed as a point of advocacy for older adults. More specifically, identification of elder abuse can be improved with the implementation of elder abuse screening tools and development of a new tool to help identify at-risk veterans before abuse even occurs.

Prevention can be achieved with increased education to raise awareness of elder abuse. Treatment of elder abuse should include the development of a standard operating procedure on elder abuse, collaboration between state and local officials, such as department of elderly affairs or adult protective services, utilization of medical foster homes, increased accessibility to home-based primary care and respite services as well as the development of shelter beds in VA-associated nursing homes for victims of elder abuse.

Last, additional research is needed to better understand the prevalence of elder abuse among veterans, identify those who are most at risk within the veteran population, and inform the development of evidence-based interventions. As the number of older adults grows, the need for programs and services is critical to ensure protection and support of this vulnerable group within society.

Elder abuse represents a mounting and alarming national health problem that is likely to continue to grow as the older adult population in the U.S. increases from 35 to 72 million by 2030.1 Elder abuse was first described in the 1970s with colloquialisms such as “granny battering” or “elder mistreatment.”2

The National Research Council defines elder abuse as “intentional actions that cause harm or a serious risk of harm to an older adult by a caregiver or other person who stands in a trust relationship to the elder, or failure by a caregiver to satisfy the elders’ basic needs or to protect the elder from harm.”3 Elder abuse can further be differentiated into 6 types of abuse: physical, emotional, sexual, financial, neglect, and self-neglect (Table).

According to a National Research Council panel, an estimated 1 to 2 million Americans aged ≥ 65 years have been injured, exploited, or otherwise mistreated by someone on whom they depend on for care or protection.4 For each reported case of elder abuse, 5 more cases go unreported.5 Neglect is the most common type of abuse, followed closely by financial exploitation. Studies suggest that those aged > 80 years are 2 to 3 times more at risk for being abused compared with individuals aged between 65 and 80 years.5 Ninety percent of elder abuse occurs at the hands of perpetrators known to the victim, including 33% by adult children, 22% by other family members, and 11% by spouses or intimate partners.5 More than half, or 53%, of alleged perpetrators of elder abuse are female, and older women are 2 times more likely than men to be abused.6 Nevertheless, it should be noted that one-third of all cases of abuse occur to men, which contradicts myths that they are seldom at risk.

Recent data show that elder abuse also is detrimental to social, law, and health systems.7 Victims of elder abuse have decreased access to support systems and fewer physical, psychological, and economic reserves.7 As a result, the impact of a single incidence of elder abuse is magnified: Victims have a higher 10-year mortality and morbidity than that of older adults who have not been abused, they have significantly higher emergency department (ED) utilization and higher hospitalization rates, and they face an increased risk for institutionalization.7,8 Economic estimates suggest that cases of elder abuse contribute to more than $5.3 billion to the annual health care expenditure in the U.S.9

On the micro level, a busy clinician who sees between 20 to 40 patients daily could encounter at least 1 victim of elder abuse per day.10 Nevertheless, a national Adult Protective Services (APS) survey recently suggested that health care professionals (HCPs) were responsible for submitting 11.1% of all elder abuse reports—with physicians accounting for only 1% of reported cases.7 Several factors may help explain the reasons that so few physicians report elder abuse, including a lack of sufficient knowledge on elder abuse definitions, types, risk factors, signs and symptoms; a misunderstanding of the reporting process; or an unwillingness to get involved. A 2005 survey of almost 400 family and internal medicine physicians showed that 63% had never asked their patients about elder abuse, 98% said there should be more education on elder abuse, and 80% felt they had not been trained to diagnose elder abuse.11

Elder Abuse Legislation

The Elder Justice Act was enacted as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in March 2010 and marked the first piece of federal legislation passed to authorize federal funds to address elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation. An Elder Justice Coordinating Counsel and an advisory board were established as national leadership in the HHS. Under this leadership and support of HHS Assistant Secretary for Aging Kathy Greenlee, an Elder Justice Interagency Working Group (EJWG) was formed in 2012 to further explore the national problem of elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation. The EJWG developed an elder abuse roadmap to provide a detailed, practical guide for teams, communities, states, and national entities, fostering a coordinated approach to reduce elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation.12

The roadmap includes initiatives such as the development of an interactive, online curriculum for legal aid and civil attorneys to identify and respond to elder abuse, what lawyers need to know about elder abuse by the Department of Justice, and the development of a voluntary national APS data system to collect national data on elder abuse by the HHS. Also there has been private stakeholder action by the Archstone Foundation/Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, which is developing a national training initiative, and the Harry and Jeannette Weinberg Center for Elder Abuse Prevention at the Hebrew Home at Riverdale in New York, which is working on the development of emergency shelters for elder abuse victims.12 The 2015 White House Conference on Aging also has made elder justice one of its 4 tracks that aims to support the “dignity, independence, and quality of life of older Americans at a time when we’re seeing a huge surge in the number of older adults.”13

VHA Response to Elder Abuse

The VHA is the largest integrated, federally funded health care system in the U.S.14 The VA census estimates that about 13 million veterans and their single surviving spouses are aged ≥ 65 years, representing about one-third of the total senior population and 45.3% of the total veteran population.15 This number is expected to rise as the 7 million Vietnam-era veterans age.15

A 2000 comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use showed that the VA patient population had poorer health status, more medical conditions, and higher medical resource utilization, including more physician visits per year, more hospital admissions per year, and more days spent in the hospital per year compared with that of the general patient population.16 Another study determined that older veterans had higher rates of lifetime trauma exposure (85%) and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology secondary to combat and war zone-related exposure (53%).17Elderly veterans also may be eligible for a wide variety of VA benefits, such as disability compensation and pension, which might place them at a higher risk for financial exploitation.18 Additionally, VA programs such as Aid & Attendance or housebound benefits award additional monies to veterans who are eligible for or are receiving a VA pension.18 General knowledge of this may negatively impact older veterans. A 2010 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report revealed that guardians stole or otherwise improperly obtained $5.4 million in assets from 158 incapacitated victims, many of whom were older adults.19

From this composite, the veteran population is at particular risk for elder abuse due to high levels of physical and psychiatric vulnerability, frailty, substance use, and caregiver dependence.

VA Policy

Elder abuse in the VA health care system is governed by VA Directive 2012-022: Reporting Cases of Abuse and Neglect, which states that as a matter of policy, all VAMCs, VA outpatient clinics, vet centers, VA community living centers, home- based primary care, home- and community-based programs, state veterans homes, and community-based outpatient clinics must comply with their state laws for reporting abuse and neglect. Specifically, relevant state statutes must be followed for the “identification, evaluation, treatment, referral, and/or mandated reporting of possible victims of physical assault, rape or sexual molestation, abuse and/or neglect of elders, spouses, partners, and children.” Each VAMC director is required to ensure that policies and procedures addressing the identification, evaluation, treatment, referral and mandatory reporting of abuse and/or neglect are in compliance with the applicable state laws.

Under this policy, any VA HCP suspecting abuse, neglect, or exploitation of an individual is responsible for providing an examination and treatment to the veteran as well as making a report to the designated state agency and documenting confirmation of the report in the electronic health record of the veteran. VA HCPs are expected to make a referral for a comprehensive social work assessment conducted by a VA social worker that includes identification of problems and determination if the veteran needs to be removed from danger. Disposition planning is an integral part of this assessment and should include the possibility of provision of additional services for veterans and their caregivers and/or possible placement in an institutional setting. Likewise, care should be taken to avoid overdiagnosis or wrongful diagnosis.

In addition, the VA Social Work Program Office has implemented standardized national social work case management documentation requirements to be used by all VA social workers assigned within patient aligned care teams (PACTs) in Primary Care. Preliminary data captured by VA social workers who completed the national standardized electronic progress notes indicate there were about 3,700 veterans during fiscal year 2014 who were assessed by the social worker with a presenting issue of “Abuse and/or Neglect.” Further study is needed to better understand the demographics, psychosocial, and medical needs of this group.

VA Research and Elder Abuse

The prevalence of elder abuse among veterans is not currently known. The 2010 GAO report stated that although it could not be determined whether allegations of abuse were widespread, hundreds of allegations of physical abuse, neglect, and financial exploitation between 1990 and 2010 were noted.19 A 2006 study that examined the prevalence, types, and intervention outcomes of elder abuse cases among a sample of veterans noted that 5.4% of evaluated veterans had a case reported on their behalf.20 Recent unpublished findings from chart reviews of all cases of elder abuse reported by the Providence and Durham VAMCs to their state’s respective APS agencies between 2006 and 2012 showed 55 reported cases at the 2 institutions during the 7-year study period. Compared with national data on elder abuse prevalence, this finding suggests a significant underreporting of elder abuse within the VA health care system. These findings are likely concordant with the lack of reporting in the community. Nevertheless, VA research on elder abuse is scant and represents an important future research priority.

Conclusion

Elder abuse has long been a taboo topic. At present there is a sense of urgency to elevate elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation as a national concern and a priority for HCPs both within the VA health care system and community. Awareness of elder abuse and neglect needs to be highlighted in order for recognition and prompt intervention to follow. Interventions should include joint federal efforts to raise public awareness of the signs of elder abuse, steps to take, and how to intervene as concerned citizen. Bridges need to be connected between health care systems and community resources, utilizing social media and educational interventions. There also is a need for parallel campaigns geared to HCPs to ensure that veterans are being screened and elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation are being appropriately diagnosed and victims cared for.

Caregiver stress and burden also needs to be considered as elder abuse and neglect are not always intentional, and as we have seen with the research already done at the VA, most elder abuse cases can be resolved by swift recognition and timely addition of services in the home in lieu of institutionalization. Discussions on elder abuse should not be feared. Rather, these conversations between citizens as well as HCPs and their clients can be viewed as a point of advocacy for older adults. More specifically, identification of elder abuse can be improved with the implementation of elder abuse screening tools and development of a new tool to help identify at-risk veterans before abuse even occurs.

Prevention can be achieved with increased education to raise awareness of elder abuse. Treatment of elder abuse should include the development of a standard operating procedure on elder abuse, collaboration between state and local officials, such as department of elderly affairs or adult protective services, utilization of medical foster homes, increased accessibility to home-based primary care and respite services as well as the development of shelter beds in VA-associated nursing homes for victims of elder abuse.

Last, additional research is needed to better understand the prevalence of elder abuse among veterans, identify those who are most at risk within the veteran population, and inform the development of evidence-based interventions. As the number of older adults grows, the need for programs and services is critical to ensure protection and support of this vulnerable group within society.

1. Policastro C, Payne B. Assessing the level of elder abuse knowledge preprofessionals possess: implications for the further development of university curriculum. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2014;26(1):12-30.

2. Gorbien MJ, Eisenstein AR. Elder abuse and neglect: an overview. Clin Geriatr Med. 2005;21(2):279-292

3. National Research Council (US) Panel to Review Risk and Prevalence of Elder Abuse and Neglect; Bonnie R, Wallace R, eds. In: Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation in an Aging America. 1st ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003.

4. Wagenaar D, Rosenbaum R, Herman S, Page C. Elder abuse education in primary care residency programs: a cluster group analysis. Fam Med. 2009;41(7):481-486.

5. National Center on Elder Abuse. The national elder abuse incidence study: final report. Administration for Community Living website. http://aoa.gov/AoA_Programs/Elder_Rights/Elder_Abuse/docs/ABuseReport_Full.pdf. Published September 1998. Accessed July 11, 2016.

6. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Half of violent victimizations of the elderly in Michigan from 2005-2009 involved serious acts of violence. Bureau of Justice Statistics website. www.bjs.gov/content/pub/press/vcerlem0509pr.cfm. Accessed July 18, 2016.

7. Mosqueda L, Dong X. Elder abuse and neglect, “I don’t care anything about going to the doctor, to be honest…” JAMA. 2011;306(5):532-540.

8. Dong X, Simon MA. Elder abuse as a risk factor for hospitalization in older persons. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):911-917.

9. Choo WY, Hairi NN, Othman S, Francis DP, Baker PRA. Interventions for preventing abuse in the elderly (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CDO10321.

10. Halphen JM, Varas GM, Sadowsky JM. Recognizing and reporting elder abuse and neglect. Geriatrics. 2009;64(7):13-18.

11. Kennedy RD. Elder abuse and neglect: the experience, knowledge, and attitudes of primary care physicians. Fam Med. 2005;37(7):481-485.

12. National Center on Elder Abuse. The elder justice roadmap: a stakeholder initiative to respond to an emerging health, justice, financial and social crisis. National Center on Elder Abuse website. http://ncea.acl.gov/library/gov_report/docs/ejrp_roadmap.pdf. Accessed July 18 2016.

13. 2015 White House Conference on Aging. (WHCOA). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. http://www.whitehouseconferenceonaging.gov/2015-WHCOA-Final-Report.pdf. Accessed on July 15 2016.

14. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs website. http://www.va.gov/about_va/vahistory.asp. Updated August 20, 2015. Accessed July 18 2016.

15. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National center for veterans analysis and statistics, Veteran population. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp.Updated April 15, 2016. Accessed July 18 2016.

16. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at veterans affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257.

17. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Posttraumatic stress symptoms among older adults: a review. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treatment/older/ptsd_symptoms_older_adults.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed July 18, 2016.

18. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans: elderly veterans. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.benefits.va.gov/persona/veteran-elderly.asp. Updated October 22, 2013. Accessed July 18, 2016.

19. United States Government Accountability Office. Guardianships: Cases of Financial Exploitation, Neglect, and Abuse of Seniors. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. GAO-10-10460.

20. Moon A, Lawson K, Carpiac M, Spaziano E. Elder Abuse and neglect among veterans in Greater Los Angeles: prevalence, types, and interventional outcomes. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2006;46(3-4):187-204.

1. Policastro C, Payne B. Assessing the level of elder abuse knowledge preprofessionals possess: implications for the further development of university curriculum. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2014;26(1):12-30.

2. Gorbien MJ, Eisenstein AR. Elder abuse and neglect: an overview. Clin Geriatr Med. 2005;21(2):279-292

3. National Research Council (US) Panel to Review Risk and Prevalence of Elder Abuse and Neglect; Bonnie R, Wallace R, eds. In: Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation in an Aging America. 1st ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003.

4. Wagenaar D, Rosenbaum R, Herman S, Page C. Elder abuse education in primary care residency programs: a cluster group analysis. Fam Med. 2009;41(7):481-486.

5. National Center on Elder Abuse. The national elder abuse incidence study: final report. Administration for Community Living website. http://aoa.gov/AoA_Programs/Elder_Rights/Elder_Abuse/docs/ABuseReport_Full.pdf. Published September 1998. Accessed July 11, 2016.

6. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Half of violent victimizations of the elderly in Michigan from 2005-2009 involved serious acts of violence. Bureau of Justice Statistics website. www.bjs.gov/content/pub/press/vcerlem0509pr.cfm. Accessed July 18, 2016.

7. Mosqueda L, Dong X. Elder abuse and neglect, “I don’t care anything about going to the doctor, to be honest…” JAMA. 2011;306(5):532-540.

8. Dong X, Simon MA. Elder abuse as a risk factor for hospitalization in older persons. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):911-917.

9. Choo WY, Hairi NN, Othman S, Francis DP, Baker PRA. Interventions for preventing abuse in the elderly (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CDO10321.

10. Halphen JM, Varas GM, Sadowsky JM. Recognizing and reporting elder abuse and neglect. Geriatrics. 2009;64(7):13-18.

11. Kennedy RD. Elder abuse and neglect: the experience, knowledge, and attitudes of primary care physicians. Fam Med. 2005;37(7):481-485.

12. National Center on Elder Abuse. The elder justice roadmap: a stakeholder initiative to respond to an emerging health, justice, financial and social crisis. National Center on Elder Abuse website. http://ncea.acl.gov/library/gov_report/docs/ejrp_roadmap.pdf. Accessed July 18 2016.

13. 2015 White House Conference on Aging. (WHCOA). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. http://www.whitehouseconferenceonaging.gov/2015-WHCOA-Final-Report.pdf. Accessed on July 15 2016.

14. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs website. http://www.va.gov/about_va/vahistory.asp. Updated August 20, 2015. Accessed July 18 2016.

15. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National center for veterans analysis and statistics, Veteran population. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp.Updated April 15, 2016. Accessed July 18 2016.

16. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at veterans affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257.

17. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Posttraumatic stress symptoms among older adults: a review. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treatment/older/ptsd_symptoms_older_adults.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed July 18, 2016.

18. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans: elderly veterans. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website. http://www.benefits.va.gov/persona/veteran-elderly.asp. Updated October 22, 2013. Accessed July 18, 2016.

19. United States Government Accountability Office. Guardianships: Cases of Financial Exploitation, Neglect, and Abuse of Seniors. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. GAO-10-10460.

20. Moon A, Lawson K, Carpiac M, Spaziano E. Elder Abuse and neglect among veterans in Greater Los Angeles: prevalence, types, and interventional outcomes. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2006;46(3-4):187-204.