User login

DOACs may be a practical option for some CLD patients

Case

A 60-year-old man with cirrhosis is admitted to the hospital with concern for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. His body mass index is 35 kg/m2. He is severely deconditioned and largely bed bound. His admission labs show thrombocytopenia (platelets 65,000/mcL) and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6. Should this patient be placed on venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis on admission?

Brief overview

Patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) have previously been considered “auto-anticoagulated” because of markers of increased bleeding risk, including a decreased platelet count and elevated INR, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time. It is being increasingly recognized, however, that CLD often represents a hypercoagulable state despite these abnormalities.1

While cirrhotic patients produce less of several procoagulant substances (such as factors II, V, VII, X, XI, XII, XIII, and fibrinogen), they are also deficient in multiple anticoagulant factors (such as proteins C and S and antithrombin) and fibrinolytics (plasminogen). While the prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time are sensitive to levels of procoagulant proteins in plasma, they do not measure response to the natural anticoagulants and therefore do not reflect an accurate picture of a cirrhotic patient’s risk of developing thrombosis. In addition, cirrhotic patients have many other risk factors for thrombosis, including poor functional status, frequent hospitalization, and elevated estrogen levels.

Overview of the data

VTE incidence among patients with CLD has varied across studies, ranging from 0.5% to 6.3%.2 A systemic review of VTE risk in cirrhotic patients concluded that they “have a significant risk of VTE, if not higher than noncirrhotic patients and this risk cannot be trivialized or ignored.”2

In a nationwide Danish case-control study, patients with cirrhosis had a 1.7 times increased risk of VTE, compared with the general population.3 Hypoalbuminemia appears to be one of the strongest associated risk factors for VTE in these patients, likely as a reflection of the degree of liver synthetic dysfunction (and therefore decreased synthesis of anticoagulant factors). One study showed that patients with an albumin of less than 1.9 g/dL had a VTE risk five times higher than patients with an albumin of 2.8 g/dL or higher.4

Prophylaxis

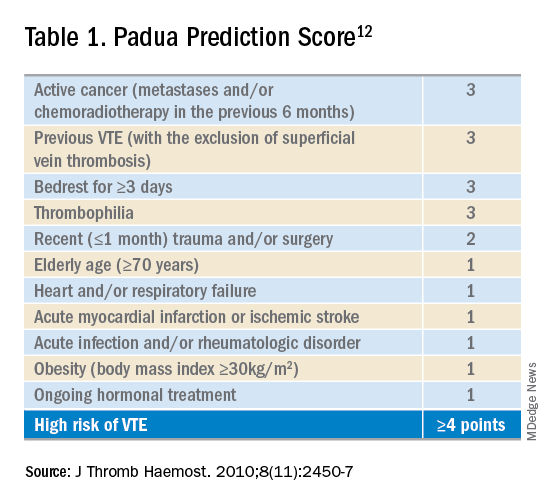

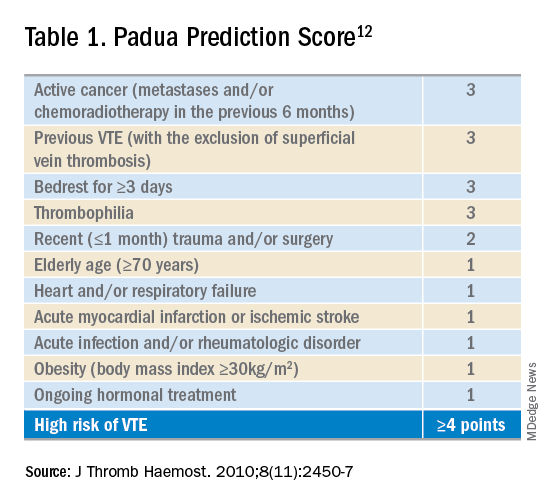

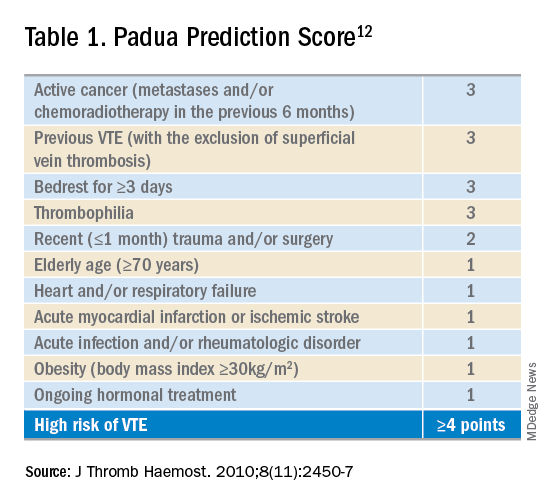

Given the increased risks of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis, how should VTE prophylaxis be managed in hospitalized patients? While current guidelines do not specifically address the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in cirrhotic patients, the Padua Predictor Score, which is used to assess VTE risk in the general hospital population, has also been shown to be helpful in the subpopulation of patients with CLD (Table 1).

In one study, cirrhotic patients who were “high risk” by Padua Predictor score were over 12 times more likely to develop VTE than those who were “low risk.”5 Bleeding risk appears to be fairly low, and similar to those patients not receiving prophylactic anticoagulation. One retrospective case series of hospitalized cirrhotic patients receiving thromboprophylaxis showed a rate of GI bleeding of 2.5% (9 of 355 patients); the rate of major bleeding was less than 1%.6

Selection of anticoagulant for VTE prophylaxis should be similar to non-CLD patients. The choice of agent (low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin) and dosing depends on factors including renal function and bodyweight. If anticoagulation is contraindicated (because of thrombocytopenia, for example), then mechanical prophylaxis should be considered.7

Treatment

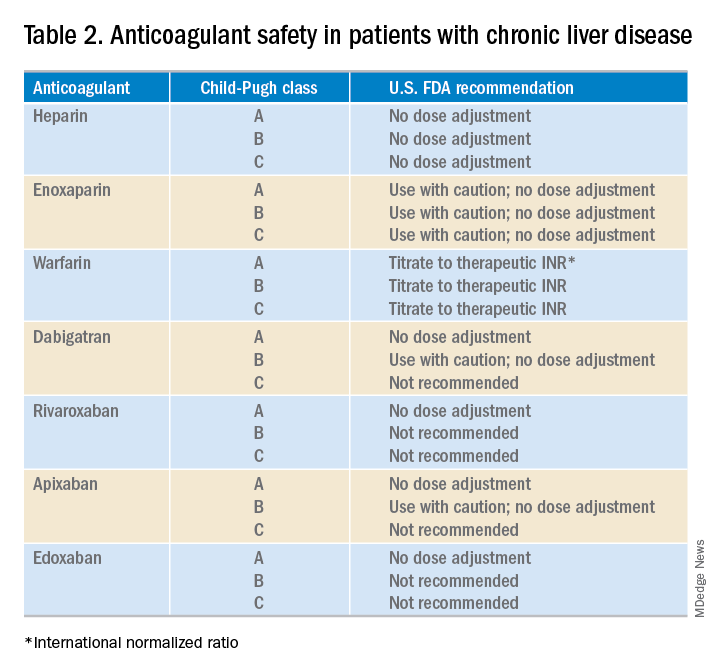

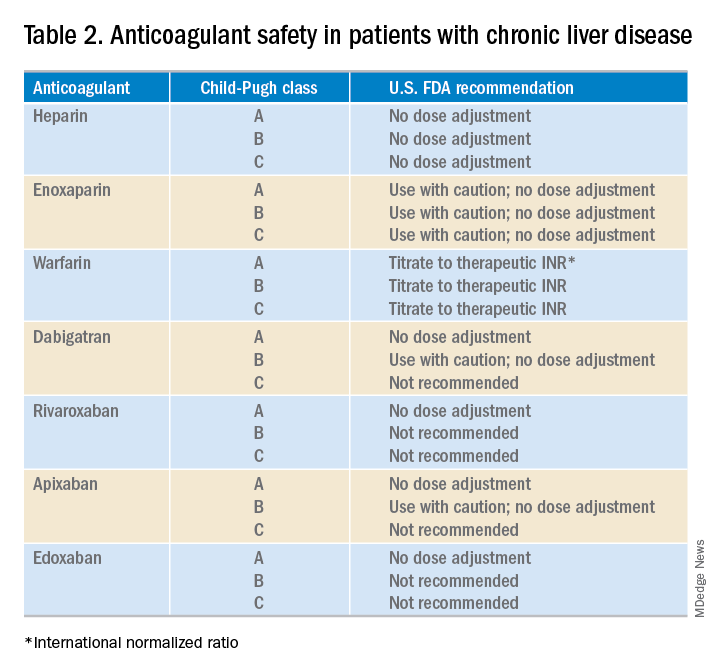

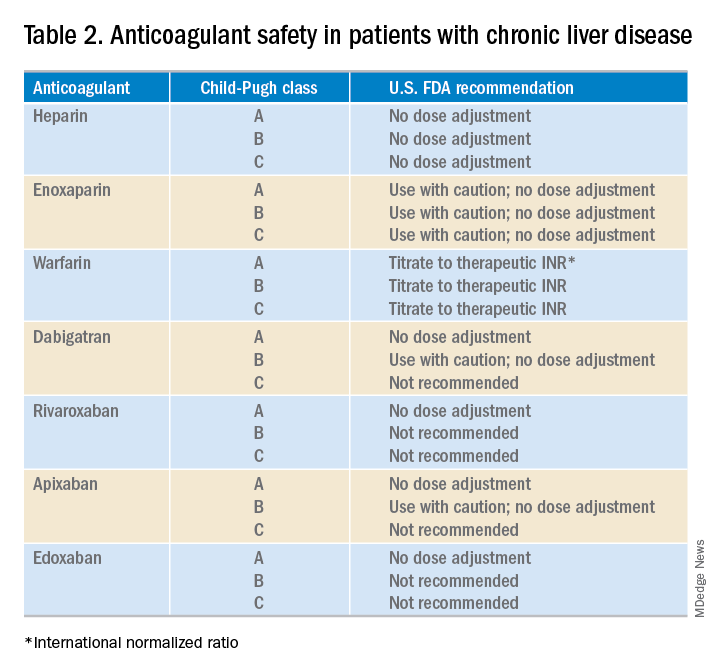

What about anticoagulation in patients with a known VTE? Food and Drug Administration safety recommendations are based on Child-Pugh class, although the current data on the safety and efficacy of full dose anticoagulation therapy for VTE in patients with cirrhosis are limited (Table 2). At this point, LMWH is often the preferred choice for anticoagulation in CLD patients. However, some limitations exist including the need for frequent subcutaneous injections and limited reliability of anti–factor Xa levels.

Cirrhotic patients often fail to achieve target anti–factor Xa levels on standard prophylactic and therapeutic doses of enoxaparin. This, however, is likely a lab anomaly as in vitro studies have shown that cirrhotic patients may show an increased response to LMWH despite reduced anti–factor Xa levels.8 Thus, LMWH remains the standard of care for many CLD patients.

The use of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) such as warfarin for VTE treatment can be difficult to manage. Traditionally CLD patients have been started on lower doses of warfarin but given their already elevated INR, this may lead to a subtherapeutic dose of VKAs. A recent study of 23 patients with cirrhosis demonstrated that a target INR of 2-3 can be reached with VKA doses similar to those in noncirrhotic patients.9 These data support the practice of using the same VKA dosing strategies for CLD patients, and selecting a starting dose based on patient parameters such as age and weight.

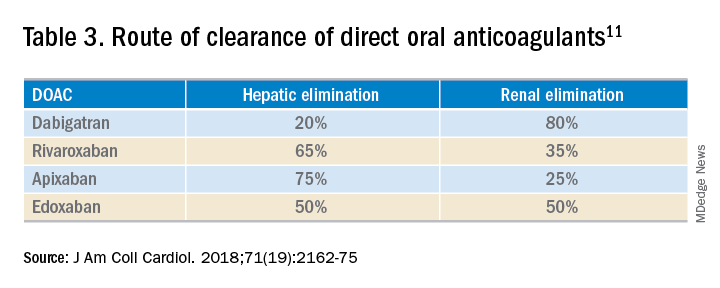

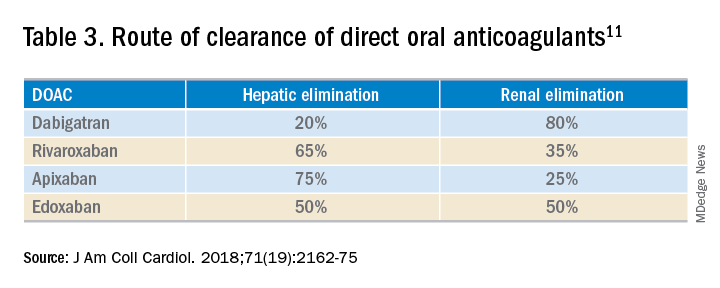

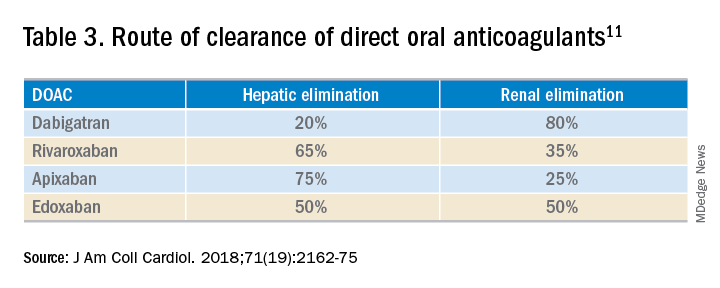

While the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for this patient population is still not a common practice, they may be a practical option for some CLD patients. A meta-analysis found that the currently used DOACs have no significant risk of drug-induced hepatic injury.10 Currently, only observational data are available to assess the benefits and risks of bleeding with DOACs in this patient population, as patients with significant liver disease were excluded from the major randomized trials.11 DOACs may also represent a complicated choice for some patients given the effect of liver injury on their metabolism (Table 3).

Application of data to the original case

This patient should be assessed for both risk of VTE and risk of bleeding during the hospital admission. CLD patients likely have a risk of VTE similar to (or even greater than) that of general medical patients. The Padua score for this patient is 4 (bed rest, body mass index) indicating that he is at high risk of VTE. While he is thrombocytopenic, he is not below the threshold for receiving anticoagulation. His INR is elevated but this does not confer any reduced risk of VTE.

Bottom line

This patient should receive VTE prophylaxis with either subcutaneous heparin or LMWH during his hospital admission.

References

1. Khoury T et al. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: An updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion. 2016 Mar;93(2):149-59.

2. Aggarwal A. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in cirrhotic patients: Systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 21;20(19):5737-45.

3. Søgaard KK et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver disease: A nationwide population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan;104(1):96-101.

4. Walsh KA et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(3):333-9.

5. Bogari H et al. Risk-assessment and pharmacological prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Thromb Res. 2014 Dec;134(6):1220-3.

6. Intagliata NM et al. Prophylactic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized cirrhosis patients is not associated with high rates of gastrointestinal bleeding. Liver Int. 2014 Jan;34(1):26-32.

7. Pincus KJ et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease and the utility of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 Jun;46(6):873-8.

8. Lishman T et al. Established and new-generation antithrombotic drugs in patients with cirrhosis – possibilities and caveats. J Hepatol. 2013 Aug;59(2):358-66.

9. Tripodi A et al. Coagulation parameters in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis treated sequentially with low molecular weight heparin and vitamin K antagonists. Dig Liver Dis. 2016 Oct;48(10):1208-13.

10. Caldeira D et al. Risk of drug-induced liver injury with the new oral anticoagulants: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2014 Apr;100(7):550-6.

11. Qamar A et al. Oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2162-75.

12. Barbar S et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: The Padua prediction score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010 Nov;8(11):2450-7.

DOACs may be a practical option for some CLD patients

DOACs may be a practical option for some CLD patients

Case

A 60-year-old man with cirrhosis is admitted to the hospital with concern for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. His body mass index is 35 kg/m2. He is severely deconditioned and largely bed bound. His admission labs show thrombocytopenia (platelets 65,000/mcL) and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6. Should this patient be placed on venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis on admission?

Brief overview

Patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) have previously been considered “auto-anticoagulated” because of markers of increased bleeding risk, including a decreased platelet count and elevated INR, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time. It is being increasingly recognized, however, that CLD often represents a hypercoagulable state despite these abnormalities.1

While cirrhotic patients produce less of several procoagulant substances (such as factors II, V, VII, X, XI, XII, XIII, and fibrinogen), they are also deficient in multiple anticoagulant factors (such as proteins C and S and antithrombin) and fibrinolytics (plasminogen). While the prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time are sensitive to levels of procoagulant proteins in plasma, they do not measure response to the natural anticoagulants and therefore do not reflect an accurate picture of a cirrhotic patient’s risk of developing thrombosis. In addition, cirrhotic patients have many other risk factors for thrombosis, including poor functional status, frequent hospitalization, and elevated estrogen levels.

Overview of the data

VTE incidence among patients with CLD has varied across studies, ranging from 0.5% to 6.3%.2 A systemic review of VTE risk in cirrhotic patients concluded that they “have a significant risk of VTE, if not higher than noncirrhotic patients and this risk cannot be trivialized or ignored.”2

In a nationwide Danish case-control study, patients with cirrhosis had a 1.7 times increased risk of VTE, compared with the general population.3 Hypoalbuminemia appears to be one of the strongest associated risk factors for VTE in these patients, likely as a reflection of the degree of liver synthetic dysfunction (and therefore decreased synthesis of anticoagulant factors). One study showed that patients with an albumin of less than 1.9 g/dL had a VTE risk five times higher than patients with an albumin of 2.8 g/dL or higher.4

Prophylaxis

Given the increased risks of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis, how should VTE prophylaxis be managed in hospitalized patients? While current guidelines do not specifically address the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in cirrhotic patients, the Padua Predictor Score, which is used to assess VTE risk in the general hospital population, has also been shown to be helpful in the subpopulation of patients with CLD (Table 1).

In one study, cirrhotic patients who were “high risk” by Padua Predictor score were over 12 times more likely to develop VTE than those who were “low risk.”5 Bleeding risk appears to be fairly low, and similar to those patients not receiving prophylactic anticoagulation. One retrospective case series of hospitalized cirrhotic patients receiving thromboprophylaxis showed a rate of GI bleeding of 2.5% (9 of 355 patients); the rate of major bleeding was less than 1%.6

Selection of anticoagulant for VTE prophylaxis should be similar to non-CLD patients. The choice of agent (low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin) and dosing depends on factors including renal function and bodyweight. If anticoagulation is contraindicated (because of thrombocytopenia, for example), then mechanical prophylaxis should be considered.7

Treatment

What about anticoagulation in patients with a known VTE? Food and Drug Administration safety recommendations are based on Child-Pugh class, although the current data on the safety and efficacy of full dose anticoagulation therapy for VTE in patients with cirrhosis are limited (Table 2). At this point, LMWH is often the preferred choice for anticoagulation in CLD patients. However, some limitations exist including the need for frequent subcutaneous injections and limited reliability of anti–factor Xa levels.

Cirrhotic patients often fail to achieve target anti–factor Xa levels on standard prophylactic and therapeutic doses of enoxaparin. This, however, is likely a lab anomaly as in vitro studies have shown that cirrhotic patients may show an increased response to LMWH despite reduced anti–factor Xa levels.8 Thus, LMWH remains the standard of care for many CLD patients.

The use of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) such as warfarin for VTE treatment can be difficult to manage. Traditionally CLD patients have been started on lower doses of warfarin but given their already elevated INR, this may lead to a subtherapeutic dose of VKAs. A recent study of 23 patients with cirrhosis demonstrated that a target INR of 2-3 can be reached with VKA doses similar to those in noncirrhotic patients.9 These data support the practice of using the same VKA dosing strategies for CLD patients, and selecting a starting dose based on patient parameters such as age and weight.

While the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for this patient population is still not a common practice, they may be a practical option for some CLD patients. A meta-analysis found that the currently used DOACs have no significant risk of drug-induced hepatic injury.10 Currently, only observational data are available to assess the benefits and risks of bleeding with DOACs in this patient population, as patients with significant liver disease were excluded from the major randomized trials.11 DOACs may also represent a complicated choice for some patients given the effect of liver injury on their metabolism (Table 3).

Application of data to the original case

This patient should be assessed for both risk of VTE and risk of bleeding during the hospital admission. CLD patients likely have a risk of VTE similar to (or even greater than) that of general medical patients. The Padua score for this patient is 4 (bed rest, body mass index) indicating that he is at high risk of VTE. While he is thrombocytopenic, he is not below the threshold for receiving anticoagulation. His INR is elevated but this does not confer any reduced risk of VTE.

Bottom line

This patient should receive VTE prophylaxis with either subcutaneous heparin or LMWH during his hospital admission.

References

1. Khoury T et al. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: An updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion. 2016 Mar;93(2):149-59.

2. Aggarwal A. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in cirrhotic patients: Systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 21;20(19):5737-45.

3. Søgaard KK et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver disease: A nationwide population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan;104(1):96-101.

4. Walsh KA et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(3):333-9.

5. Bogari H et al. Risk-assessment and pharmacological prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Thromb Res. 2014 Dec;134(6):1220-3.

6. Intagliata NM et al. Prophylactic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized cirrhosis patients is not associated with high rates of gastrointestinal bleeding. Liver Int. 2014 Jan;34(1):26-32.

7. Pincus KJ et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease and the utility of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 Jun;46(6):873-8.

8. Lishman T et al. Established and new-generation antithrombotic drugs in patients with cirrhosis – possibilities and caveats. J Hepatol. 2013 Aug;59(2):358-66.

9. Tripodi A et al. Coagulation parameters in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis treated sequentially with low molecular weight heparin and vitamin K antagonists. Dig Liver Dis. 2016 Oct;48(10):1208-13.

10. Caldeira D et al. Risk of drug-induced liver injury with the new oral anticoagulants: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2014 Apr;100(7):550-6.

11. Qamar A et al. Oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2162-75.

12. Barbar S et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: The Padua prediction score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010 Nov;8(11):2450-7.

Case

A 60-year-old man with cirrhosis is admitted to the hospital with concern for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. His body mass index is 35 kg/m2. He is severely deconditioned and largely bed bound. His admission labs show thrombocytopenia (platelets 65,000/mcL) and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6. Should this patient be placed on venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis on admission?

Brief overview

Patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) have previously been considered “auto-anticoagulated” because of markers of increased bleeding risk, including a decreased platelet count and elevated INR, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time. It is being increasingly recognized, however, that CLD often represents a hypercoagulable state despite these abnormalities.1

While cirrhotic patients produce less of several procoagulant substances (such as factors II, V, VII, X, XI, XII, XIII, and fibrinogen), they are also deficient in multiple anticoagulant factors (such as proteins C and S and antithrombin) and fibrinolytics (plasminogen). While the prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time are sensitive to levels of procoagulant proteins in plasma, they do not measure response to the natural anticoagulants and therefore do not reflect an accurate picture of a cirrhotic patient’s risk of developing thrombosis. In addition, cirrhotic patients have many other risk factors for thrombosis, including poor functional status, frequent hospitalization, and elevated estrogen levels.

Overview of the data

VTE incidence among patients with CLD has varied across studies, ranging from 0.5% to 6.3%.2 A systemic review of VTE risk in cirrhotic patients concluded that they “have a significant risk of VTE, if not higher than noncirrhotic patients and this risk cannot be trivialized or ignored.”2

In a nationwide Danish case-control study, patients with cirrhosis had a 1.7 times increased risk of VTE, compared with the general population.3 Hypoalbuminemia appears to be one of the strongest associated risk factors for VTE in these patients, likely as a reflection of the degree of liver synthetic dysfunction (and therefore decreased synthesis of anticoagulant factors). One study showed that patients with an albumin of less than 1.9 g/dL had a VTE risk five times higher than patients with an albumin of 2.8 g/dL or higher.4

Prophylaxis

Given the increased risks of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis, how should VTE prophylaxis be managed in hospitalized patients? While current guidelines do not specifically address the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in cirrhotic patients, the Padua Predictor Score, which is used to assess VTE risk in the general hospital population, has also been shown to be helpful in the subpopulation of patients with CLD (Table 1).

In one study, cirrhotic patients who were “high risk” by Padua Predictor score were over 12 times more likely to develop VTE than those who were “low risk.”5 Bleeding risk appears to be fairly low, and similar to those patients not receiving prophylactic anticoagulation. One retrospective case series of hospitalized cirrhotic patients receiving thromboprophylaxis showed a rate of GI bleeding of 2.5% (9 of 355 patients); the rate of major bleeding was less than 1%.6

Selection of anticoagulant for VTE prophylaxis should be similar to non-CLD patients. The choice of agent (low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin) and dosing depends on factors including renal function and bodyweight. If anticoagulation is contraindicated (because of thrombocytopenia, for example), then mechanical prophylaxis should be considered.7

Treatment

What about anticoagulation in patients with a known VTE? Food and Drug Administration safety recommendations are based on Child-Pugh class, although the current data on the safety and efficacy of full dose anticoagulation therapy for VTE in patients with cirrhosis are limited (Table 2). At this point, LMWH is often the preferred choice for anticoagulation in CLD patients. However, some limitations exist including the need for frequent subcutaneous injections and limited reliability of anti–factor Xa levels.

Cirrhotic patients often fail to achieve target anti–factor Xa levels on standard prophylactic and therapeutic doses of enoxaparin. This, however, is likely a lab anomaly as in vitro studies have shown that cirrhotic patients may show an increased response to LMWH despite reduced anti–factor Xa levels.8 Thus, LMWH remains the standard of care for many CLD patients.

The use of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) such as warfarin for VTE treatment can be difficult to manage. Traditionally CLD patients have been started on lower doses of warfarin but given their already elevated INR, this may lead to a subtherapeutic dose of VKAs. A recent study of 23 patients with cirrhosis demonstrated that a target INR of 2-3 can be reached with VKA doses similar to those in noncirrhotic patients.9 These data support the practice of using the same VKA dosing strategies for CLD patients, and selecting a starting dose based on patient parameters such as age and weight.

While the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for this patient population is still not a common practice, they may be a practical option for some CLD patients. A meta-analysis found that the currently used DOACs have no significant risk of drug-induced hepatic injury.10 Currently, only observational data are available to assess the benefits and risks of bleeding with DOACs in this patient population, as patients with significant liver disease were excluded from the major randomized trials.11 DOACs may also represent a complicated choice for some patients given the effect of liver injury on their metabolism (Table 3).

Application of data to the original case

This patient should be assessed for both risk of VTE and risk of bleeding during the hospital admission. CLD patients likely have a risk of VTE similar to (or even greater than) that of general medical patients. The Padua score for this patient is 4 (bed rest, body mass index) indicating that he is at high risk of VTE. While he is thrombocytopenic, he is not below the threshold for receiving anticoagulation. His INR is elevated but this does not confer any reduced risk of VTE.

Bottom line

This patient should receive VTE prophylaxis with either subcutaneous heparin or LMWH during his hospital admission.

References

1. Khoury T et al. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: An updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion. 2016 Mar;93(2):149-59.

2. Aggarwal A. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in cirrhotic patients: Systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 21;20(19):5737-45.

3. Søgaard KK et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver disease: A nationwide population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan;104(1):96-101.

4. Walsh KA et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(3):333-9.

5. Bogari H et al. Risk-assessment and pharmacological prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Thromb Res. 2014 Dec;134(6):1220-3.

6. Intagliata NM et al. Prophylactic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized cirrhosis patients is not associated with high rates of gastrointestinal bleeding. Liver Int. 2014 Jan;34(1):26-32.

7. Pincus KJ et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease and the utility of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 Jun;46(6):873-8.

8. Lishman T et al. Established and new-generation antithrombotic drugs in patients with cirrhosis – possibilities and caveats. J Hepatol. 2013 Aug;59(2):358-66.

9. Tripodi A et al. Coagulation parameters in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis treated sequentially with low molecular weight heparin and vitamin K antagonists. Dig Liver Dis. 2016 Oct;48(10):1208-13.

10. Caldeira D et al. Risk of drug-induced liver injury with the new oral anticoagulants: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2014 Apr;100(7):550-6.

11. Qamar A et al. Oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2162-75.

12. Barbar S et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: The Padua prediction score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010 Nov;8(11):2450-7.