User login

Approximately a century ago, Francis Peabody taught that “the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.”1 His advice remains true today. Despite the advent of novel diagnostic tests, technologically sophisticated interventional procedures, and life-saving medications, perhaps the most important skill a bedside clinician can use is the ability to connect with patients.

The literature on patient-physician interaction is vast2-11 and generally indicates that exemplary bedside clinicians are able to interact well with patients by being competent, trustworthy, personable, empathetic, and effective communicators. “Etiquette-based medicine,” first proposed by Kahn,12 emphasizes the importance of certain behaviors from physicians, such as introducing yourself and

Yet, improving patient-physician interactions remains necessary. A recent systematic review reported that almost half of the reviewed studies on the patient-physician relationship published between 2000 and 2014 conveyed the idea that the patient-physician relationship is deteriorating.13

As part of a broader study to understand the behaviors and approaches of exemplary inpatient attending physicians,14-16 we examined how 12 carefully selected physicians interacted with their patients during inpatient teaching rounds.

METHODS

Overview

We conducted a multisite study using an exploratory, qualitative approach to inquiry, which has been described previously.14-16 Our primary purpose was to study the attributes and behaviors of outstanding general medicine attendings in the setting of inpatient rounds. The focus of this article is on the attendings’ interactions with patients.

We used a modified snowball sampling approach17 to identify 12 exemplary physicians. First, we contacted individuals throughout the United States who were known to the principal investigator (S.S.) and asked for suggestions of excellent clinician educators (also referred to as attendings) for potential inclusion in the study. In addition to these personal contacts, other individuals unknown to the investigative team were contacted and asked to provide suggestions for attendings to include in the study. Specifically, the US News & World Report 2015 Top Medical Schools: Research Rankings,18 which are widely used to represent the best U.S. hospitals, were reviewed in an effort to identify attendings from a broad range of medical schools. Using this list, we identified other medical schools that were in the top 25 and were not already represented. We contacted the division chiefs of general internal (or hospital) medicine, chairs and chiefs of departments of internal medicine, and internal medicine residency program directors from these medical schools and asked for recommendations of attendings from both within and outside their institutions whom they considered to be great inpatient teachers.

This sampling method resulted in 59 potential participants. An internet search was conducted on each potential participant to obtain further information about the individuals and their institutions. Both personal characteristics (medical education, training, and educational awards) and organizational characteristics (geographic location, hospital size and affiliation, and patient population) were considered so that a variety of organizations and backgrounds were represented. Through this process, the list was narrowed to 16 attendings who were contacted to participate in the study, of which 12 agreed. The number of attendings examined was appropriate because saturation of metathemes can occur in as little as 6 interviews, and data saturation occurs at 12 interviews.19 The participants were asked to provide a list of their current learners (ie, residents and medical students) and 6 to 10 former learners to contact for interviews and focus groups.

Data Collection

Observations

Two researchers conducted the one-day site visits. One was a physician (S.S.) and the other a medical anthropologist (M.H.), and both have extensive experience in qualitative methods. The only exception was the site visit at the principal investigator’s own institution, which was conducted by the medical anthropologist and a nonpracticing physician who was unknown to the participants. The team structure varied slightly among different institutions but in general was composed of 1 attending, 1 senior medical resident, 1 to 2 interns, and approximately 2 medical students. Each site visit began with observing the attendings (n = 12) and current learners (n = 57) on morning rounds, which included their interactions with patients. These observations lasted approximately 2 to 3 hours. The observers took handwritten field notes, paying particular attention to group interactions, teaching approaches, and patient interactions. The observers stood outside the medical team circle and remained silent during rounds so as to be unobtrusive to the teams’ discussions. The observers discussed and compared their notes after each site visit.

Interviews and Focus Groups

The research team also conducted individual, semistructured interviews with the attendings (n = 12), focus groups with their current teams (n = 46), and interviews or focus groups with their former learners (n = 26). Current learners were asked open-ended questions about their roles on the teams, their opinions of the attendings, and the care the attendings provide to their patients. Because they were observed during rounds, the researchers asked for clarification about specific interactions observed during the teaching rounds. Depending on availability and location, former learners either participated in in-person focus groups or interviews on the day of the site visit, or in a later telephone interview. All interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed.

This study was deemed to be exempt from regulation by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All participants were informed that their participation was completely voluntary and that they could refuse to answer any question.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach,20 which involves reading through the data to identify patterns (and create codes) that relate to behaviors, experiences, meanings, and activities. The patterns are then grouped into themes to help further explain the findings.21 The research team members (S.S. and M.H.) met after the first site visit and developed initial ideas about meanings and possible patterns. One team member (M.H.) read all the transcripts from the site visit and, based on the data, developed a codebook to be used for this study. This process was repeated after every site visit, and the coding definitions were refined as necessary. All transcripts were reviewed to apply any new codes when they developed. NVivo® 10 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) was used to assist with the qualitative data analysis.

To ensure consistency and identify relationships between codes, code reports listing all the data linked to a specific code were generated after all the field notes and transcripts were coded. Once verified, codes were grouped based on similarities and relationships into prominent themes related to physician-patient interactions by 2 team members (S.S. and M.H.), though all members reviewed them and concurred.

RESULTS

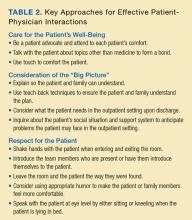

C are for the Patient’s Well-Being

The attendings we observed appeared to openly care for their patients’ well-being and were focused on the patients’ wants and needs. We noted that attendings were generally very attentive to the patients’ comfort. For example, we observed one attending sending the senior resident to find the patient’s nurse in order to obtain additional pain medications. The attending said to the patient several times, “I’m sorry you’re in so much pain.” When the team was leaving, she asked the intern to stay with the patient until the medications had been administered.

The attendings we observed could also be considered patient advocates, ensuring that patients received superb care. As one learner said about an attending who was attempting to have his patient listed for a liver transplant, “He is the biggest advocate for the patient that I have ever seen.” Regarding the balance between learning biomedical concepts and advocacy, another learner noted the following: “… there is always a teaching aspect, but he always makes sure that everything is taken care of for the patient…”

Building rapport creates and sustains bonds between people. Even though most of the attendings we observed primarily cared for hospitalized patients and had little long-term continuity with them, the attendings tended to take special care to talk with their patients about topics other than medicine to form a bond. This bonding between attending and patient was appreciated by learners. “Probably the most important thing I learned about patient care would be taking the time and really developing that relationship with patients,” said one of the former learners we interviewed. “There’s a question that he asks to a lot of our patients,” one learner told us, “especially our elderly patients, that [is], ‘What’s the most memorable moment in your life?’ So, he asks that question, and patient[s] open up and will share.”

The attendings often used touch to further solidify their relationships with their patients. We observed one attending who would touch her patients’ arms or knees when she was talking with them. Another attending would always shake the patient’s hand when leaving. Another attending would often lay his hand on the patient’s shoulder and help the patient sit up during the physical examination. Such humanistic behavior was noticed by learners. “She does a lot of comforting touch, particularly at the end of an exam,” said a current learner.

C onsideration of the “Big Picture”

Our exemplary attendings kept the “big picture” (that is, the patient’s overall medical and social needs) in clear focus. They behaved in a way to ensure that the patients understood the key points of their care and explained so the patients and families could understand. A current learner said, “[The attending] really makes sure that the patient understands what’s going on. And she always asks them, ‘What do you understand, what do you know, how can we fill in any blanks?’ And that makes the patient really involved in their own care, which I think is important.” This reflection was supported by direct observations. Attendings posed the following questions at the conclusion of patient interactions: “Tell me what you know.” “Tell me what our plan is.” “What did the lung doctors tell you yesterday?” These questions, which have been termed “teach-back” and are crucial for health literacy, were not meant to quiz the patient but rather to ensure the patient and family understood the plan.

We noticed that the attendings effectively explained clinical details and the plan of care to the patient while avoiding medical jargon. The following is an example of one interaction with a patient: “You threw up and created a tear in the food tube. Air got from that into the middle of the chest, not into the lungs. Air isn’t normally there. If it is just air, the body will reabsorb [it]... But we worry about bacteria getting in with the air. We need to figure out if it is an infection. We’re still trying to figure it out. Hang in there with us.” One learner commented, “… since we do bedside presentations, he has a great way of translating our gibberish, basically, to real language the patient understands.”

Finally, the attendings anticipated what patients would need in the outpatient setting. We observed that attendings stressed what the next steps would be during transitions of care. As one learner put it, “But he also thinks ahead; what do they need as an outpatient?” Another current learner commented on how another attending always asked about the social situations of his patients stating, “And then there is the social part of it. So, he is very much interested [in] where do they live? What is their support system? So, I think it has been a very holistic approach to patient care.”

R espect for the Patient

The attendings we observed were steadfastly respectful toward patients. As one attending told us, “The patient’s room is sacred space, and it’s a privilege for us to be there. And if we don’t earn that privilege, then we don’t get to go there.” We observed that the attendings generally referred to the patient as Mr. or Ms. (last name) rather than the patient’s first name unless the patient insisted. We also noticed that many of the attendings would introduce the team members to the patients or ask each member to introduce himself or herself. They also tended to leave the room and patient the way they were found, for example, by pushing the patient’s bedside table so that it was back within his or her reach or placing socks back onto the patient’s feet.

We noted that many of our attendings used appropriate humor with patients and families. As one learner explained, “I think Dr. [attending] makes most of our patients laugh during rounds. I don’t know if you noticed, but he really puts a smile on their face[s] whenever he walks in. … Maybe it would catch them off guard the first day, but after that, they are so happy to see him.”

Finally, we noticed that several of our attendings made sure to meet the patient at eye level during discussions by either kneeling or sitting on a chair. One of the attendings put it this way: “That’s a horrible power dynamic when you’re an inpatient and you’re sick and someone’s standing over you telling you things, and I like to be able to make eye contact with people, and often times that requires me to kneel down or to sit on a stool or to sit on the bed. … I feel like you’re able to connect with the people in a much better way…” Learners viewed this behavior favorably. As one told us, “[The attending] gets down to their level and makes sure that all of their questions are answered. So that is one thing that other attendings don’t necessarily do.”

DISCUSSION

In our national, qualitative study of 12 exemplary attending physicians, we found that these clinicians generally exhibited the following behaviors with patients. First, they were personable and caring and made significant attempts to connect with their patients. This occasionally took the form of using touch to comfort patients. Second, they tended to seek the “big picture” and tried to understand what patients would need upon hospital discharge. They communicated plans clearly to patients and families and inquired if those plans were understood. Finally, they showed respect toward their patients without fail. Such respect took many forms but included leaving the patient and room exactly as they were found and speaking with patients at eye level.

Our findings are largely consistent with other key studies in this field. Not surprisingly, the attendings we observed adhered to the major suggestions that Branch and colleagues2 put forth more than 15 years ago to improve the teaching of the humanistic dimension of the patient-physician relationship. Examples include greeting the patient, introducing team members and explaining each person’s role, asking open-ended questions, providing patient education, placing oneself at the same level as the patient, using appropriate touch, and being respectful. Weissmann et al.22 also found similar themes in their study of teaching physicians at 4 universities from 2003 to 2004. In that study, role-modeling was the primary method used by physician educators to teach the humanistic aspects of medical care, including nonverbal communication (eg, touch and eye contact), demonstration of respect, and building a personal connection with the patients.22In a focus group-based study performed at a teaching hospital in Boston, Ramani and Orlander23 concluded that both participating teachers and learners considered the patient’s bedside as a valuable venue to learn humanistic skills. Unfortunately, they also noted that there has been a decline in bedside teaching related to various factors, including documentation requirements and electronic medical records.23 Our attendings all demonstrated the value of teaching at a patient’s bedside. Not only could physical examination skills be demonstrated but role-modeling of interpersonal skills could be observed by learners.

Block and colleagues24 observed 29 interns in 732 patient encounters in 2 Baltimore training programs using Kahn’s “etiquette-based medicine” behaviors as a guide.12 They found that interns introduced themselves 40% of the time, explained their role 37% of the time, touched patients on 65% of visits (including as part of the physical examination), asked open-ended questions 75% of the time, and sat down with patients during only 9% of visits.24 Tackett et al.7 observed 24 hospitalists who collectively cared for 226 unique patients in 3 Baltimore-area hospitals. They found that each of the following behaviors was performed less than 30% of the time: explains role in care, shakes hand, and sits down.7 However, our attendings appeared to adhere to these behaviors to a much higher extent, though we did not quantify the interactions. This lends support to the notion that effective patient-physician interactions are the foundation of great teaching.

The attendings we observed (most of whom are inpatient based) tended to the contextual issues of the patients, such as their home environments and social support. Our exemplary physicians did what they could to ensure that patients received the appropriate follow-up care upon discharge.

Our study has important limitations. First, it was conducted in a limited number of US hospitals. The institutions represented were generally large, research-intensive, academic medical centers. Therefore, our findings may not apply to settings that are different from the hospitals studied. Second, our study included only 12 attendings and their learners, which may also limit the study’s generalizability. Third, we focused exclusively on teaching within general medicine rounds. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to other subspecialties. Fourth, attendings were selected through a nonexhaustive method, increasing the potential for selection bias. However, the multisite design, the modified snowball sampling, and the inclusion of several types of institutions in the final participant pool introduced diversity to the final list. Former-learner responses were subject to recall bias. Finally, the study design is susceptible to observer bias. Attempts to reduce this included the diversity of the observers (ie, both a clinician and a nonclinician, the latter of whom was unfamiliar with medical education) and review of the data and coding by multiple research team members to ensure validity. Although we cannot discount the potential role of a Hawthorne effect on our data collection, the research team attempted to mitigate this by standing apart from the care teams and remaining unobtrusive during observations.

Limitations notwithstanding, we believe that our multisite study is important given the longstanding imperative to improve patient-physician interactions. We found empirical support for behaviors proposed by Branch and colleagues2 and Kahn12 in order to enhance these relationships. While others have studied attendings and their current learners,22 we add to the literature by also examining former learners’ perspectives on how the attendings’ teaching and role-modeling have created and sustained a lasting impact. The key findings of our national, qualitative study (care for the patient’s well-being, consideration of the “big picture,” and respect for the patient) can be readily adopted and honed by physicians to improve their interactions with hospitalized patients.

A cknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

F unding

Dr. Saint provided funding for this study using a University of Michigan endowment.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88(12):877-882. PubMed

2. Branch WT, Jr., Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067-1074. PubMed

3. Frankel RM. Relationship-centered care and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1163-1165. PubMed

4. Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423-1433. PubMed

5. Osmun WE, Brown JB, Stewart M, Graham S. Patients’ attitudes to comforting touch in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:2411-2416. PubMed

6. Strasser F, Palmer JL, Willey J, et al. Impact of physician sitting versus standing during inpatient oncology consultations: patients’ preference and perception of compassion and duration. A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(5):489-497. PubMed

7. Tackett S, Tad-y D, Rios R, Kisuule F, Wright S. Appraising the practice of etiquette-based medicine in the inpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):908-913. PubMed

8. Gallagher TH, Levinson W. A prescription for protecting the doctor-patient relationship. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(2, pt 1):61-68. PubMed

9. Braddock CH, 3rd, Snyder L. The doctor will see you shortly. The ethical significance of time for the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1057-1062. PubMed

10. Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903-918. PubMed

11. Lee SJ, Back AL, Block SD, Stewart SK. Enhancing physician-patient communication. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2002:464-483. PubMed

12. Kahn MW. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. PubMed

13. Hoff T, Collinson GE. How Do We Talk About the Physician-Patient Relationship? What the Nonempirical Literature Tells Us. Med Care Res Rev. 2016. PubMed

14. Houchens N, Harrod M, Moody S, Fowler KE, Saint S. Techniques and behaviors associated with exemplary inpatient general medicine teaching: an exploratory qualitative study. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):503-509. PubMed

15. Houchens N, Harrod M, Fowler KE, Moody S., Saint S. Teaching “how” to think instead of “what” to think: how great inpatient physicians foster clinical reasoning. Am J Med. In Press.

16. Harrod M, Saint S, Stock RW. Teaching Inpatient Medicine: What Every Physician Needs to Know. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017.

17. Richards L, Morse J. README FIRST for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Methods. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 2013.

18. US News and World Report. Best Medical Schools: Research. 2014; http://grad-schools.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/research-rankings. Accessed on September 16, 2016.

19. Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59-82.

20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. PubMed

21. Aronson J. A pragmatic view of thematic analysis. Qual Rep. 1995;2(1):1-3.

22. Weissmann PF, Branch WT, Gracey CF, Haidet P, Frankel RM. Role modeling humanistic behavior: learning bedside manner from the experts. Acad Med. 2006;81(7):661-667. PubMed

23. Ramani S, Orlander JD. Human dimensions in bedside teaching: focus group discussions of teachers and learners. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):312-318. PubMed

24. Block L, Hutzler L, Habicht R, et al. Do internal medicine interns practice etiquette-based communication? A critical look at the inpatient encounter. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):631-634. PubMed

Approximately a century ago, Francis Peabody taught that “the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.”1 His advice remains true today. Despite the advent of novel diagnostic tests, technologically sophisticated interventional procedures, and life-saving medications, perhaps the most important skill a bedside clinician can use is the ability to connect with patients.

The literature on patient-physician interaction is vast2-11 and generally indicates that exemplary bedside clinicians are able to interact well with patients by being competent, trustworthy, personable, empathetic, and effective communicators. “Etiquette-based medicine,” first proposed by Kahn,12 emphasizes the importance of certain behaviors from physicians, such as introducing yourself and

Yet, improving patient-physician interactions remains necessary. A recent systematic review reported that almost half of the reviewed studies on the patient-physician relationship published between 2000 and 2014 conveyed the idea that the patient-physician relationship is deteriorating.13

As part of a broader study to understand the behaviors and approaches of exemplary inpatient attending physicians,14-16 we examined how 12 carefully selected physicians interacted with their patients during inpatient teaching rounds.

METHODS

Overview

We conducted a multisite study using an exploratory, qualitative approach to inquiry, which has been described previously.14-16 Our primary purpose was to study the attributes and behaviors of outstanding general medicine attendings in the setting of inpatient rounds. The focus of this article is on the attendings’ interactions with patients.

We used a modified snowball sampling approach17 to identify 12 exemplary physicians. First, we contacted individuals throughout the United States who were known to the principal investigator (S.S.) and asked for suggestions of excellent clinician educators (also referred to as attendings) for potential inclusion in the study. In addition to these personal contacts, other individuals unknown to the investigative team were contacted and asked to provide suggestions for attendings to include in the study. Specifically, the US News & World Report 2015 Top Medical Schools: Research Rankings,18 which are widely used to represent the best U.S. hospitals, were reviewed in an effort to identify attendings from a broad range of medical schools. Using this list, we identified other medical schools that were in the top 25 and were not already represented. We contacted the division chiefs of general internal (or hospital) medicine, chairs and chiefs of departments of internal medicine, and internal medicine residency program directors from these medical schools and asked for recommendations of attendings from both within and outside their institutions whom they considered to be great inpatient teachers.

This sampling method resulted in 59 potential participants. An internet search was conducted on each potential participant to obtain further information about the individuals and their institutions. Both personal characteristics (medical education, training, and educational awards) and organizational characteristics (geographic location, hospital size and affiliation, and patient population) were considered so that a variety of organizations and backgrounds were represented. Through this process, the list was narrowed to 16 attendings who were contacted to participate in the study, of which 12 agreed. The number of attendings examined was appropriate because saturation of metathemes can occur in as little as 6 interviews, and data saturation occurs at 12 interviews.19 The participants were asked to provide a list of their current learners (ie, residents and medical students) and 6 to 10 former learners to contact for interviews and focus groups.

Data Collection

Observations

Two researchers conducted the one-day site visits. One was a physician (S.S.) and the other a medical anthropologist (M.H.), and both have extensive experience in qualitative methods. The only exception was the site visit at the principal investigator’s own institution, which was conducted by the medical anthropologist and a nonpracticing physician who was unknown to the participants. The team structure varied slightly among different institutions but in general was composed of 1 attending, 1 senior medical resident, 1 to 2 interns, and approximately 2 medical students. Each site visit began with observing the attendings (n = 12) and current learners (n = 57) on morning rounds, which included their interactions with patients. These observations lasted approximately 2 to 3 hours. The observers took handwritten field notes, paying particular attention to group interactions, teaching approaches, and patient interactions. The observers stood outside the medical team circle and remained silent during rounds so as to be unobtrusive to the teams’ discussions. The observers discussed and compared their notes after each site visit.

Interviews and Focus Groups

The research team also conducted individual, semistructured interviews with the attendings (n = 12), focus groups with their current teams (n = 46), and interviews or focus groups with their former learners (n = 26). Current learners were asked open-ended questions about their roles on the teams, their opinions of the attendings, and the care the attendings provide to their patients. Because they were observed during rounds, the researchers asked for clarification about specific interactions observed during the teaching rounds. Depending on availability and location, former learners either participated in in-person focus groups or interviews on the day of the site visit, or in a later telephone interview. All interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed.

This study was deemed to be exempt from regulation by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All participants were informed that their participation was completely voluntary and that they could refuse to answer any question.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach,20 which involves reading through the data to identify patterns (and create codes) that relate to behaviors, experiences, meanings, and activities. The patterns are then grouped into themes to help further explain the findings.21 The research team members (S.S. and M.H.) met after the first site visit and developed initial ideas about meanings and possible patterns. One team member (M.H.) read all the transcripts from the site visit and, based on the data, developed a codebook to be used for this study. This process was repeated after every site visit, and the coding definitions were refined as necessary. All transcripts were reviewed to apply any new codes when they developed. NVivo® 10 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) was used to assist with the qualitative data analysis.

To ensure consistency and identify relationships between codes, code reports listing all the data linked to a specific code were generated after all the field notes and transcripts were coded. Once verified, codes were grouped based on similarities and relationships into prominent themes related to physician-patient interactions by 2 team members (S.S. and M.H.), though all members reviewed them and concurred.

RESULTS

C are for the Patient’s Well-Being

The attendings we observed appeared to openly care for their patients’ well-being and were focused on the patients’ wants and needs. We noted that attendings were generally very attentive to the patients’ comfort. For example, we observed one attending sending the senior resident to find the patient’s nurse in order to obtain additional pain medications. The attending said to the patient several times, “I’m sorry you’re in so much pain.” When the team was leaving, she asked the intern to stay with the patient until the medications had been administered.

The attendings we observed could also be considered patient advocates, ensuring that patients received superb care. As one learner said about an attending who was attempting to have his patient listed for a liver transplant, “He is the biggest advocate for the patient that I have ever seen.” Regarding the balance between learning biomedical concepts and advocacy, another learner noted the following: “… there is always a teaching aspect, but he always makes sure that everything is taken care of for the patient…”

Building rapport creates and sustains bonds between people. Even though most of the attendings we observed primarily cared for hospitalized patients and had little long-term continuity with them, the attendings tended to take special care to talk with their patients about topics other than medicine to form a bond. This bonding between attending and patient was appreciated by learners. “Probably the most important thing I learned about patient care would be taking the time and really developing that relationship with patients,” said one of the former learners we interviewed. “There’s a question that he asks to a lot of our patients,” one learner told us, “especially our elderly patients, that [is], ‘What’s the most memorable moment in your life?’ So, he asks that question, and patient[s] open up and will share.”

The attendings often used touch to further solidify their relationships with their patients. We observed one attending who would touch her patients’ arms or knees when she was talking with them. Another attending would always shake the patient’s hand when leaving. Another attending would often lay his hand on the patient’s shoulder and help the patient sit up during the physical examination. Such humanistic behavior was noticed by learners. “She does a lot of comforting touch, particularly at the end of an exam,” said a current learner.

C onsideration of the “Big Picture”

Our exemplary attendings kept the “big picture” (that is, the patient’s overall medical and social needs) in clear focus. They behaved in a way to ensure that the patients understood the key points of their care and explained so the patients and families could understand. A current learner said, “[The attending] really makes sure that the patient understands what’s going on. And she always asks them, ‘What do you understand, what do you know, how can we fill in any blanks?’ And that makes the patient really involved in their own care, which I think is important.” This reflection was supported by direct observations. Attendings posed the following questions at the conclusion of patient interactions: “Tell me what you know.” “Tell me what our plan is.” “What did the lung doctors tell you yesterday?” These questions, which have been termed “teach-back” and are crucial for health literacy, were not meant to quiz the patient but rather to ensure the patient and family understood the plan.

We noticed that the attendings effectively explained clinical details and the plan of care to the patient while avoiding medical jargon. The following is an example of one interaction with a patient: “You threw up and created a tear in the food tube. Air got from that into the middle of the chest, not into the lungs. Air isn’t normally there. If it is just air, the body will reabsorb [it]... But we worry about bacteria getting in with the air. We need to figure out if it is an infection. We’re still trying to figure it out. Hang in there with us.” One learner commented, “… since we do bedside presentations, he has a great way of translating our gibberish, basically, to real language the patient understands.”

Finally, the attendings anticipated what patients would need in the outpatient setting. We observed that attendings stressed what the next steps would be during transitions of care. As one learner put it, “But he also thinks ahead; what do they need as an outpatient?” Another current learner commented on how another attending always asked about the social situations of his patients stating, “And then there is the social part of it. So, he is very much interested [in] where do they live? What is their support system? So, I think it has been a very holistic approach to patient care.”

R espect for the Patient

The attendings we observed were steadfastly respectful toward patients. As one attending told us, “The patient’s room is sacred space, and it’s a privilege for us to be there. And if we don’t earn that privilege, then we don’t get to go there.” We observed that the attendings generally referred to the patient as Mr. or Ms. (last name) rather than the patient’s first name unless the patient insisted. We also noticed that many of the attendings would introduce the team members to the patients or ask each member to introduce himself or herself. They also tended to leave the room and patient the way they were found, for example, by pushing the patient’s bedside table so that it was back within his or her reach or placing socks back onto the patient’s feet.

We noted that many of our attendings used appropriate humor with patients and families. As one learner explained, “I think Dr. [attending] makes most of our patients laugh during rounds. I don’t know if you noticed, but he really puts a smile on their face[s] whenever he walks in. … Maybe it would catch them off guard the first day, but after that, they are so happy to see him.”

Finally, we noticed that several of our attendings made sure to meet the patient at eye level during discussions by either kneeling or sitting on a chair. One of the attendings put it this way: “That’s a horrible power dynamic when you’re an inpatient and you’re sick and someone’s standing over you telling you things, and I like to be able to make eye contact with people, and often times that requires me to kneel down or to sit on a stool or to sit on the bed. … I feel like you’re able to connect with the people in a much better way…” Learners viewed this behavior favorably. As one told us, “[The attending] gets down to their level and makes sure that all of their questions are answered. So that is one thing that other attendings don’t necessarily do.”

DISCUSSION

In our national, qualitative study of 12 exemplary attending physicians, we found that these clinicians generally exhibited the following behaviors with patients. First, they were personable and caring and made significant attempts to connect with their patients. This occasionally took the form of using touch to comfort patients. Second, they tended to seek the “big picture” and tried to understand what patients would need upon hospital discharge. They communicated plans clearly to patients and families and inquired if those plans were understood. Finally, they showed respect toward their patients without fail. Such respect took many forms but included leaving the patient and room exactly as they were found and speaking with patients at eye level.

Our findings are largely consistent with other key studies in this field. Not surprisingly, the attendings we observed adhered to the major suggestions that Branch and colleagues2 put forth more than 15 years ago to improve the teaching of the humanistic dimension of the patient-physician relationship. Examples include greeting the patient, introducing team members and explaining each person’s role, asking open-ended questions, providing patient education, placing oneself at the same level as the patient, using appropriate touch, and being respectful. Weissmann et al.22 also found similar themes in their study of teaching physicians at 4 universities from 2003 to 2004. In that study, role-modeling was the primary method used by physician educators to teach the humanistic aspects of medical care, including nonverbal communication (eg, touch and eye contact), demonstration of respect, and building a personal connection with the patients.22In a focus group-based study performed at a teaching hospital in Boston, Ramani and Orlander23 concluded that both participating teachers and learners considered the patient’s bedside as a valuable venue to learn humanistic skills. Unfortunately, they also noted that there has been a decline in bedside teaching related to various factors, including documentation requirements and electronic medical records.23 Our attendings all demonstrated the value of teaching at a patient’s bedside. Not only could physical examination skills be demonstrated but role-modeling of interpersonal skills could be observed by learners.

Block and colleagues24 observed 29 interns in 732 patient encounters in 2 Baltimore training programs using Kahn’s “etiquette-based medicine” behaviors as a guide.12 They found that interns introduced themselves 40% of the time, explained their role 37% of the time, touched patients on 65% of visits (including as part of the physical examination), asked open-ended questions 75% of the time, and sat down with patients during only 9% of visits.24 Tackett et al.7 observed 24 hospitalists who collectively cared for 226 unique patients in 3 Baltimore-area hospitals. They found that each of the following behaviors was performed less than 30% of the time: explains role in care, shakes hand, and sits down.7 However, our attendings appeared to adhere to these behaviors to a much higher extent, though we did not quantify the interactions. This lends support to the notion that effective patient-physician interactions are the foundation of great teaching.

The attendings we observed (most of whom are inpatient based) tended to the contextual issues of the patients, such as their home environments and social support. Our exemplary physicians did what they could to ensure that patients received the appropriate follow-up care upon discharge.

Our study has important limitations. First, it was conducted in a limited number of US hospitals. The institutions represented were generally large, research-intensive, academic medical centers. Therefore, our findings may not apply to settings that are different from the hospitals studied. Second, our study included only 12 attendings and their learners, which may also limit the study’s generalizability. Third, we focused exclusively on teaching within general medicine rounds. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to other subspecialties. Fourth, attendings were selected through a nonexhaustive method, increasing the potential for selection bias. However, the multisite design, the modified snowball sampling, and the inclusion of several types of institutions in the final participant pool introduced diversity to the final list. Former-learner responses were subject to recall bias. Finally, the study design is susceptible to observer bias. Attempts to reduce this included the diversity of the observers (ie, both a clinician and a nonclinician, the latter of whom was unfamiliar with medical education) and review of the data and coding by multiple research team members to ensure validity. Although we cannot discount the potential role of a Hawthorne effect on our data collection, the research team attempted to mitigate this by standing apart from the care teams and remaining unobtrusive during observations.

Limitations notwithstanding, we believe that our multisite study is important given the longstanding imperative to improve patient-physician interactions. We found empirical support for behaviors proposed by Branch and colleagues2 and Kahn12 in order to enhance these relationships. While others have studied attendings and their current learners,22 we add to the literature by also examining former learners’ perspectives on how the attendings’ teaching and role-modeling have created and sustained a lasting impact. The key findings of our national, qualitative study (care for the patient’s well-being, consideration of the “big picture,” and respect for the patient) can be readily adopted and honed by physicians to improve their interactions with hospitalized patients.

A cknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

F unding

Dr. Saint provided funding for this study using a University of Michigan endowment.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Approximately a century ago, Francis Peabody taught that “the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.”1 His advice remains true today. Despite the advent of novel diagnostic tests, technologically sophisticated interventional procedures, and life-saving medications, perhaps the most important skill a bedside clinician can use is the ability to connect with patients.

The literature on patient-physician interaction is vast2-11 and generally indicates that exemplary bedside clinicians are able to interact well with patients by being competent, trustworthy, personable, empathetic, and effective communicators. “Etiquette-based medicine,” first proposed by Kahn,12 emphasizes the importance of certain behaviors from physicians, such as introducing yourself and

Yet, improving patient-physician interactions remains necessary. A recent systematic review reported that almost half of the reviewed studies on the patient-physician relationship published between 2000 and 2014 conveyed the idea that the patient-physician relationship is deteriorating.13

As part of a broader study to understand the behaviors and approaches of exemplary inpatient attending physicians,14-16 we examined how 12 carefully selected physicians interacted with their patients during inpatient teaching rounds.

METHODS

Overview

We conducted a multisite study using an exploratory, qualitative approach to inquiry, which has been described previously.14-16 Our primary purpose was to study the attributes and behaviors of outstanding general medicine attendings in the setting of inpatient rounds. The focus of this article is on the attendings’ interactions with patients.

We used a modified snowball sampling approach17 to identify 12 exemplary physicians. First, we contacted individuals throughout the United States who were known to the principal investigator (S.S.) and asked for suggestions of excellent clinician educators (also referred to as attendings) for potential inclusion in the study. In addition to these personal contacts, other individuals unknown to the investigative team were contacted and asked to provide suggestions for attendings to include in the study. Specifically, the US News & World Report 2015 Top Medical Schools: Research Rankings,18 which are widely used to represent the best U.S. hospitals, were reviewed in an effort to identify attendings from a broad range of medical schools. Using this list, we identified other medical schools that were in the top 25 and were not already represented. We contacted the division chiefs of general internal (or hospital) medicine, chairs and chiefs of departments of internal medicine, and internal medicine residency program directors from these medical schools and asked for recommendations of attendings from both within and outside their institutions whom they considered to be great inpatient teachers.

This sampling method resulted in 59 potential participants. An internet search was conducted on each potential participant to obtain further information about the individuals and their institutions. Both personal characteristics (medical education, training, and educational awards) and organizational characteristics (geographic location, hospital size and affiliation, and patient population) were considered so that a variety of organizations and backgrounds were represented. Through this process, the list was narrowed to 16 attendings who were contacted to participate in the study, of which 12 agreed. The number of attendings examined was appropriate because saturation of metathemes can occur in as little as 6 interviews, and data saturation occurs at 12 interviews.19 The participants were asked to provide a list of their current learners (ie, residents and medical students) and 6 to 10 former learners to contact for interviews and focus groups.

Data Collection

Observations

Two researchers conducted the one-day site visits. One was a physician (S.S.) and the other a medical anthropologist (M.H.), and both have extensive experience in qualitative methods. The only exception was the site visit at the principal investigator’s own institution, which was conducted by the medical anthropologist and a nonpracticing physician who was unknown to the participants. The team structure varied slightly among different institutions but in general was composed of 1 attending, 1 senior medical resident, 1 to 2 interns, and approximately 2 medical students. Each site visit began with observing the attendings (n = 12) and current learners (n = 57) on morning rounds, which included their interactions with patients. These observations lasted approximately 2 to 3 hours. The observers took handwritten field notes, paying particular attention to group interactions, teaching approaches, and patient interactions. The observers stood outside the medical team circle and remained silent during rounds so as to be unobtrusive to the teams’ discussions. The observers discussed and compared their notes after each site visit.

Interviews and Focus Groups

The research team also conducted individual, semistructured interviews with the attendings (n = 12), focus groups with their current teams (n = 46), and interviews or focus groups with their former learners (n = 26). Current learners were asked open-ended questions about their roles on the teams, their opinions of the attendings, and the care the attendings provide to their patients. Because they were observed during rounds, the researchers asked for clarification about specific interactions observed during the teaching rounds. Depending on availability and location, former learners either participated in in-person focus groups or interviews on the day of the site visit, or in a later telephone interview. All interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed.

This study was deemed to be exempt from regulation by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All participants were informed that their participation was completely voluntary and that they could refuse to answer any question.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach,20 which involves reading through the data to identify patterns (and create codes) that relate to behaviors, experiences, meanings, and activities. The patterns are then grouped into themes to help further explain the findings.21 The research team members (S.S. and M.H.) met after the first site visit and developed initial ideas about meanings and possible patterns. One team member (M.H.) read all the transcripts from the site visit and, based on the data, developed a codebook to be used for this study. This process was repeated after every site visit, and the coding definitions were refined as necessary. All transcripts were reviewed to apply any new codes when they developed. NVivo® 10 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) was used to assist with the qualitative data analysis.

To ensure consistency and identify relationships between codes, code reports listing all the data linked to a specific code were generated after all the field notes and transcripts were coded. Once verified, codes were grouped based on similarities and relationships into prominent themes related to physician-patient interactions by 2 team members (S.S. and M.H.), though all members reviewed them and concurred.

RESULTS

C are for the Patient’s Well-Being

The attendings we observed appeared to openly care for their patients’ well-being and were focused on the patients’ wants and needs. We noted that attendings were generally very attentive to the patients’ comfort. For example, we observed one attending sending the senior resident to find the patient’s nurse in order to obtain additional pain medications. The attending said to the patient several times, “I’m sorry you’re in so much pain.” When the team was leaving, she asked the intern to stay with the patient until the medications had been administered.

The attendings we observed could also be considered patient advocates, ensuring that patients received superb care. As one learner said about an attending who was attempting to have his patient listed for a liver transplant, “He is the biggest advocate for the patient that I have ever seen.” Regarding the balance between learning biomedical concepts and advocacy, another learner noted the following: “… there is always a teaching aspect, but he always makes sure that everything is taken care of for the patient…”

Building rapport creates and sustains bonds between people. Even though most of the attendings we observed primarily cared for hospitalized patients and had little long-term continuity with them, the attendings tended to take special care to talk with their patients about topics other than medicine to form a bond. This bonding between attending and patient was appreciated by learners. “Probably the most important thing I learned about patient care would be taking the time and really developing that relationship with patients,” said one of the former learners we interviewed. “There’s a question that he asks to a lot of our patients,” one learner told us, “especially our elderly patients, that [is], ‘What’s the most memorable moment in your life?’ So, he asks that question, and patient[s] open up and will share.”

The attendings often used touch to further solidify their relationships with their patients. We observed one attending who would touch her patients’ arms or knees when she was talking with them. Another attending would always shake the patient’s hand when leaving. Another attending would often lay his hand on the patient’s shoulder and help the patient sit up during the physical examination. Such humanistic behavior was noticed by learners. “She does a lot of comforting touch, particularly at the end of an exam,” said a current learner.

C onsideration of the “Big Picture”

Our exemplary attendings kept the “big picture” (that is, the patient’s overall medical and social needs) in clear focus. They behaved in a way to ensure that the patients understood the key points of their care and explained so the patients and families could understand. A current learner said, “[The attending] really makes sure that the patient understands what’s going on. And she always asks them, ‘What do you understand, what do you know, how can we fill in any blanks?’ And that makes the patient really involved in their own care, which I think is important.” This reflection was supported by direct observations. Attendings posed the following questions at the conclusion of patient interactions: “Tell me what you know.” “Tell me what our plan is.” “What did the lung doctors tell you yesterday?” These questions, which have been termed “teach-back” and are crucial for health literacy, were not meant to quiz the patient but rather to ensure the patient and family understood the plan.

We noticed that the attendings effectively explained clinical details and the plan of care to the patient while avoiding medical jargon. The following is an example of one interaction with a patient: “You threw up and created a tear in the food tube. Air got from that into the middle of the chest, not into the lungs. Air isn’t normally there. If it is just air, the body will reabsorb [it]... But we worry about bacteria getting in with the air. We need to figure out if it is an infection. We’re still trying to figure it out. Hang in there with us.” One learner commented, “… since we do bedside presentations, he has a great way of translating our gibberish, basically, to real language the patient understands.”

Finally, the attendings anticipated what patients would need in the outpatient setting. We observed that attendings stressed what the next steps would be during transitions of care. As one learner put it, “But he also thinks ahead; what do they need as an outpatient?” Another current learner commented on how another attending always asked about the social situations of his patients stating, “And then there is the social part of it. So, he is very much interested [in] where do they live? What is their support system? So, I think it has been a very holistic approach to patient care.”

R espect for the Patient

The attendings we observed were steadfastly respectful toward patients. As one attending told us, “The patient’s room is sacred space, and it’s a privilege for us to be there. And if we don’t earn that privilege, then we don’t get to go there.” We observed that the attendings generally referred to the patient as Mr. or Ms. (last name) rather than the patient’s first name unless the patient insisted. We also noticed that many of the attendings would introduce the team members to the patients or ask each member to introduce himself or herself. They also tended to leave the room and patient the way they were found, for example, by pushing the patient’s bedside table so that it was back within his or her reach or placing socks back onto the patient’s feet.

We noted that many of our attendings used appropriate humor with patients and families. As one learner explained, “I think Dr. [attending] makes most of our patients laugh during rounds. I don’t know if you noticed, but he really puts a smile on their face[s] whenever he walks in. … Maybe it would catch them off guard the first day, but after that, they are so happy to see him.”

Finally, we noticed that several of our attendings made sure to meet the patient at eye level during discussions by either kneeling or sitting on a chair. One of the attendings put it this way: “That’s a horrible power dynamic when you’re an inpatient and you’re sick and someone’s standing over you telling you things, and I like to be able to make eye contact with people, and often times that requires me to kneel down or to sit on a stool or to sit on the bed. … I feel like you’re able to connect with the people in a much better way…” Learners viewed this behavior favorably. As one told us, “[The attending] gets down to their level and makes sure that all of their questions are answered. So that is one thing that other attendings don’t necessarily do.”

DISCUSSION

In our national, qualitative study of 12 exemplary attending physicians, we found that these clinicians generally exhibited the following behaviors with patients. First, they were personable and caring and made significant attempts to connect with their patients. This occasionally took the form of using touch to comfort patients. Second, they tended to seek the “big picture” and tried to understand what patients would need upon hospital discharge. They communicated plans clearly to patients and families and inquired if those plans were understood. Finally, they showed respect toward their patients without fail. Such respect took many forms but included leaving the patient and room exactly as they were found and speaking with patients at eye level.

Our findings are largely consistent with other key studies in this field. Not surprisingly, the attendings we observed adhered to the major suggestions that Branch and colleagues2 put forth more than 15 years ago to improve the teaching of the humanistic dimension of the patient-physician relationship. Examples include greeting the patient, introducing team members and explaining each person’s role, asking open-ended questions, providing patient education, placing oneself at the same level as the patient, using appropriate touch, and being respectful. Weissmann et al.22 also found similar themes in their study of teaching physicians at 4 universities from 2003 to 2004. In that study, role-modeling was the primary method used by physician educators to teach the humanistic aspects of medical care, including nonverbal communication (eg, touch and eye contact), demonstration of respect, and building a personal connection with the patients.22In a focus group-based study performed at a teaching hospital in Boston, Ramani and Orlander23 concluded that both participating teachers and learners considered the patient’s bedside as a valuable venue to learn humanistic skills. Unfortunately, they also noted that there has been a decline in bedside teaching related to various factors, including documentation requirements and electronic medical records.23 Our attendings all demonstrated the value of teaching at a patient’s bedside. Not only could physical examination skills be demonstrated but role-modeling of interpersonal skills could be observed by learners.

Block and colleagues24 observed 29 interns in 732 patient encounters in 2 Baltimore training programs using Kahn’s “etiquette-based medicine” behaviors as a guide.12 They found that interns introduced themselves 40% of the time, explained their role 37% of the time, touched patients on 65% of visits (including as part of the physical examination), asked open-ended questions 75% of the time, and sat down with patients during only 9% of visits.24 Tackett et al.7 observed 24 hospitalists who collectively cared for 226 unique patients in 3 Baltimore-area hospitals. They found that each of the following behaviors was performed less than 30% of the time: explains role in care, shakes hand, and sits down.7 However, our attendings appeared to adhere to these behaviors to a much higher extent, though we did not quantify the interactions. This lends support to the notion that effective patient-physician interactions are the foundation of great teaching.

The attendings we observed (most of whom are inpatient based) tended to the contextual issues of the patients, such as their home environments and social support. Our exemplary physicians did what they could to ensure that patients received the appropriate follow-up care upon discharge.

Our study has important limitations. First, it was conducted in a limited number of US hospitals. The institutions represented were generally large, research-intensive, academic medical centers. Therefore, our findings may not apply to settings that are different from the hospitals studied. Second, our study included only 12 attendings and their learners, which may also limit the study’s generalizability. Third, we focused exclusively on teaching within general medicine rounds. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to other subspecialties. Fourth, attendings were selected through a nonexhaustive method, increasing the potential for selection bias. However, the multisite design, the modified snowball sampling, and the inclusion of several types of institutions in the final participant pool introduced diversity to the final list. Former-learner responses were subject to recall bias. Finally, the study design is susceptible to observer bias. Attempts to reduce this included the diversity of the observers (ie, both a clinician and a nonclinician, the latter of whom was unfamiliar with medical education) and review of the data and coding by multiple research team members to ensure validity. Although we cannot discount the potential role of a Hawthorne effect on our data collection, the research team attempted to mitigate this by standing apart from the care teams and remaining unobtrusive during observations.

Limitations notwithstanding, we believe that our multisite study is important given the longstanding imperative to improve patient-physician interactions. We found empirical support for behaviors proposed by Branch and colleagues2 and Kahn12 in order to enhance these relationships. While others have studied attendings and their current learners,22 we add to the literature by also examining former learners’ perspectives on how the attendings’ teaching and role-modeling have created and sustained a lasting impact. The key findings of our national, qualitative study (care for the patient’s well-being, consideration of the “big picture,” and respect for the patient) can be readily adopted and honed by physicians to improve their interactions with hospitalized patients.

A cknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

F unding

Dr. Saint provided funding for this study using a University of Michigan endowment.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88(12):877-882. PubMed

2. Branch WT, Jr., Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067-1074. PubMed

3. Frankel RM. Relationship-centered care and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1163-1165. PubMed

4. Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423-1433. PubMed

5. Osmun WE, Brown JB, Stewart M, Graham S. Patients’ attitudes to comforting touch in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:2411-2416. PubMed

6. Strasser F, Palmer JL, Willey J, et al. Impact of physician sitting versus standing during inpatient oncology consultations: patients’ preference and perception of compassion and duration. A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(5):489-497. PubMed

7. Tackett S, Tad-y D, Rios R, Kisuule F, Wright S. Appraising the practice of etiquette-based medicine in the inpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):908-913. PubMed

8. Gallagher TH, Levinson W. A prescription for protecting the doctor-patient relationship. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(2, pt 1):61-68. PubMed

9. Braddock CH, 3rd, Snyder L. The doctor will see you shortly. The ethical significance of time for the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1057-1062. PubMed

10. Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903-918. PubMed

11. Lee SJ, Back AL, Block SD, Stewart SK. Enhancing physician-patient communication. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2002:464-483. PubMed

12. Kahn MW. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. PubMed

13. Hoff T, Collinson GE. How Do We Talk About the Physician-Patient Relationship? What the Nonempirical Literature Tells Us. Med Care Res Rev. 2016. PubMed

14. Houchens N, Harrod M, Moody S, Fowler KE, Saint S. Techniques and behaviors associated with exemplary inpatient general medicine teaching: an exploratory qualitative study. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):503-509. PubMed

15. Houchens N, Harrod M, Fowler KE, Moody S., Saint S. Teaching “how” to think instead of “what” to think: how great inpatient physicians foster clinical reasoning. Am J Med. In Press.

16. Harrod M, Saint S, Stock RW. Teaching Inpatient Medicine: What Every Physician Needs to Know. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017.

17. Richards L, Morse J. README FIRST for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Methods. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 2013.

18. US News and World Report. Best Medical Schools: Research. 2014; http://grad-schools.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/research-rankings. Accessed on September 16, 2016.

19. Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59-82.

20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. PubMed

21. Aronson J. A pragmatic view of thematic analysis. Qual Rep. 1995;2(1):1-3.

22. Weissmann PF, Branch WT, Gracey CF, Haidet P, Frankel RM. Role modeling humanistic behavior: learning bedside manner from the experts. Acad Med. 2006;81(7):661-667. PubMed

23. Ramani S, Orlander JD. Human dimensions in bedside teaching: focus group discussions of teachers and learners. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):312-318. PubMed

24. Block L, Hutzler L, Habicht R, et al. Do internal medicine interns practice etiquette-based communication? A critical look at the inpatient encounter. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):631-634. PubMed

1. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88(12):877-882. PubMed

2. Branch WT, Jr., Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067-1074. PubMed

3. Frankel RM. Relationship-centered care and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1163-1165. PubMed

4. Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423-1433. PubMed

5. Osmun WE, Brown JB, Stewart M, Graham S. Patients’ attitudes to comforting touch in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:2411-2416. PubMed

6. Strasser F, Palmer JL, Willey J, et al. Impact of physician sitting versus standing during inpatient oncology consultations: patients’ preference and perception of compassion and duration. A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(5):489-497. PubMed

7. Tackett S, Tad-y D, Rios R, Kisuule F, Wright S. Appraising the practice of etiquette-based medicine in the inpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):908-913. PubMed

8. Gallagher TH, Levinson W. A prescription for protecting the doctor-patient relationship. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(2, pt 1):61-68. PubMed

9. Braddock CH, 3rd, Snyder L. The doctor will see you shortly. The ethical significance of time for the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1057-1062. PubMed

10. Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903-918. PubMed

11. Lee SJ, Back AL, Block SD, Stewart SK. Enhancing physician-patient communication. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2002:464-483. PubMed

12. Kahn MW. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. PubMed

13. Hoff T, Collinson GE. How Do We Talk About the Physician-Patient Relationship? What the Nonempirical Literature Tells Us. Med Care Res Rev. 2016. PubMed

14. Houchens N, Harrod M, Moody S, Fowler KE, Saint S. Techniques and behaviors associated with exemplary inpatient general medicine teaching: an exploratory qualitative study. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):503-509. PubMed

15. Houchens N, Harrod M, Fowler KE, Moody S., Saint S. Teaching “how” to think instead of “what” to think: how great inpatient physicians foster clinical reasoning. Am J Med. In Press.

16. Harrod M, Saint S, Stock RW. Teaching Inpatient Medicine: What Every Physician Needs to Know. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017.

17. Richards L, Morse J. README FIRST for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Methods. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 2013.

18. US News and World Report. Best Medical Schools: Research. 2014; http://grad-schools.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/research-rankings. Accessed on September 16, 2016.

19. Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59-82.

20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. PubMed

21. Aronson J. A pragmatic view of thematic analysis. Qual Rep. 1995;2(1):1-3.

22. Weissmann PF, Branch WT, Gracey CF, Haidet P, Frankel RM. Role modeling humanistic behavior: learning bedside manner from the experts. Acad Med. 2006;81(7):661-667. PubMed

23. Ramani S, Orlander JD. Human dimensions in bedside teaching: focus group discussions of teachers and learners. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):312-318. PubMed

24. Block L, Hutzler L, Habicht R, et al. Do internal medicine interns practice etiquette-based communication? A critical look at the inpatient encounter. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):631-634. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine