User login

The chances are good that at least one patient you saw today could have been provided a better environment to foster your patient-physician relationship. A 2020 Gallup poll revealed that an estimated 5.6% of US adults identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT).1 Based on the estimated US population of 331.7 million individuals on December 3, 2020, this means that approximately 18.6 million identified as LGBT and could potentially require health care services.2 These numbers highlight the increasing need within the medical community to provide quality and accessible care to the LGBT community, and dermatologists have a role to play. They treat conditions that are apparent to the patient and others around them, attracting those that may not be motivated to see different physicians. They can not only help with skin diseases that affect all patients but also can train other physicians to screen for some dermatologic diseases that may have a higher prevalence within the LGBT community. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to help patients better reflect themselves through both surgical and nonsurgical modalities.

Demographics and Definitions

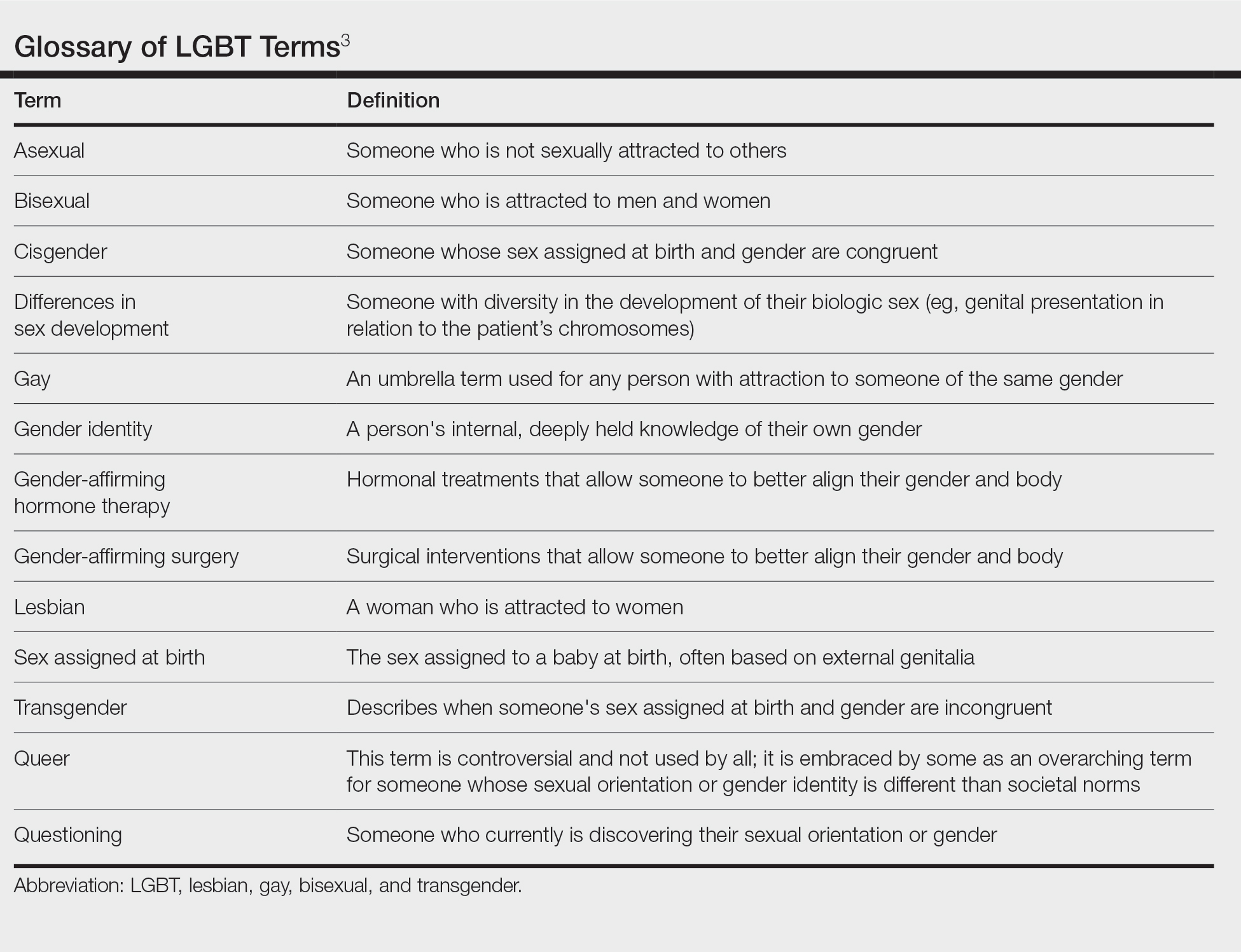

To discuss this topic effectively, it is important to define LGBT terms (Table).3 As a disclaimer, language is fluid. Despite a word or term currently being used and accepted, it quickly can become obsolete. A clinician can always do research, follow the lead of the patient, and respectfully ask questions if there is ever confusion surrounding terminology. Patients do not expect every physician they encounter to be an expert in this subject. What is most important is that patients are approached with an open mind and humility with the goal of providing optimal care.

Although the federal government now uses the term sexual and gender minorities (SGM), the more specific terms lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender usually are preferred.3,4 Other letters are at times added to the acronym LGBT, including Q for questioning or queer, I for intersex, and A for asexual; all of these letters are under the larger SGM umbrella. Because LGBT is the most commonly used acronym in the daily vernacular, it will be the default for this article.

A term describing sexual orientation does not necessarily describe sexual practices. A woman who identifies as straight may have sex with both men and women, and a gay man may not have sex at all. To be more descriptive regarding sexual practices, one may use the terms men who have sex with men or women who have sex with women.3 Because of this nuance, it is important to elicit a sexual history when speaking to all patients in a forward nonjudgmental manner.

The term transgender is used to describe people whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. Two examples of transgender individuals would be transgender women who were assigned male at birth and transgender men who were assigned female at birth. The term transgender is used in opposition to the term cisgender, which is applied to a person whose gender and sex assigned at birth align.3 When a transgender patient presents to a physician, they may want to discuss methods of gender affirmation or transitioning. These terms encompass any action a person may take to align their body or gender expression with that of the gender they identify with. This could be in the form of gender-affirming hormone therapy (ie, estrogen or testosterone treatment) or gender-affirming surgery (ie, “top” and “bottom” surgeries, in which someone surgically treats their chest or genitals, respectively).3

Creating a Safe Space

The physician is responsible for providing a safe space for patients to disclose medically pertinent information. It is then the job of the dermatologist to be cognizant of health concerns that directly affect the LGBT population and to be prepared if one of these concerns should arise. A safe space consists of both the physical location in which the patient encounter will occur and the people that will be conducting and assisting in the patient encounter. Safe spaces provide a patient with reassurance that they will receive care in a judgement-free location. To create a safe space, both the physical and interpersonal aspects must be addressed to provide an environment that strengthens the patient-physician alliance.

Dermatology residents often spend more time with patients than their attending physicians, providing them the opportunity to foster robust relationships with those served. Although they may not be able to change the physical environment, residents can advocate for patients in their departments and show solidarity in subtle ways. One way to show support for the LGBT community is to publicly display a symbol of solidarity, which could be done by wearing a symbol of support on a white coat lapel. Although there are many designs and styles to choose from, one example is the American Medical Student Association pins that combine the caduceus (a common symbol for medicine) with a rainbow design.5 Whichever symbol is chosen, this small gesture allows patients to immediately know that their physician is an ally. Residents also can encourage their department to add a rainbow flag, a pink triangle, or another symbol somewhere prominent in the check-in area that conveys a message of support.6 Many institutions require residents to perform quality improvement projects. The resident can make a substantial difference in their patients’ experiences by revising their office’s intake forms as a quality improvement project, which can be done by including a section on assigned sex at birth separate from gender.7 When inquiring about gender, in addition to “male” and “female,” a space can be left for people that do not identify with the traditional binary. When asking about sexual orientation, inclusive language options can be provided with additional space for self-identification. Finally, residents can incorporate pronouns below their name in their email signature to normalize this disclosure of information.8 These small changes can have a substantial impact on the health care experience of SGM patients.

Medical Problems Encountered

The previously described changes can be implemented by residents to provide better care to SGM patients, a group usually considered to be more burdened by physical and psychological diseases.9 Furthermore, dermatologists can provide care for these patients in ways that other physicians cannot. There are special considerations for LGBT patients, as some dermatologic conditions may be more common in this patient population.

Prior studies have shown that men who have sex with men have a higher rate of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections, and potentially nonmelanoma skin cancer.10-14 Transgender women also have been found to have higher rates of HIV, in addition to a higher incidence of anal human papillomavirus.15,16 Women who have sex with women have been shown to see physicians less frequently and to be less up to date on their pertinent cancer-related screenings.10,17 Although these associations should not dictate the patient encounter, awareness of them will lead to better patient care. Such awareness also can provide further motivation for dermatologists to discuss safe sexual practices, potential initiation of pre-exposure prophylactic antiretroviral therapy, sun-protective practices, and the importance of following up with a primary physician for examinations and age-specific cancer screening.

Transgender patients may present with unique dermatologic concerns. For transgender male patients, testosterone therapy can cause acne breakouts and androgenetic alopecia. Usually considered worse during the start of treatment, hormone-related acne can be managed with topical retinoids, topical and oral antibiotics, and isotretinoin (if severe).18,19 The iPLEDGE system necessary for prescribing isotretinoin to patients in the United States recently has changed its language to “patients who can get pregnant” and “patients who cannot get pregnant,” following urging by the medical community for inclusivity and progress.20,21 This change creates an inclusive space where registration is no longer centered around gender and instead focuses on the presence of anatomy. Although androgenetic alopecia is a side effect of hormone therapy, it may not be unwanted.18 Discussion about patient desires is important. If the alopecia is unwanted, the Endocrine Society recommends treating cisgender and transgender patients the same in terms of treatment modalities.22

Transgender female patients also can experience dermatologic manifestations of gender-affirming hormone therapy. Melasma may develop secondary to estrogen replacement and can be treated with topical bleaching creams, lasers, and phototherapy.23 Hair removal may be pursued for patients with refractory unwanted body hair, with laser hair removal being the most commonly pursued treatment. Patients also may desire cosmetic procedures, such as botulinum toxin or fillers, to augment their physical appearance.24 Providing these services to patients may allow them to better express themselves and live authentically.

Final Thoughts

There is no way to summarize the experience of everyone within a community. Each person has different thoughts, values, and goals. It also is impossible to encompass every topic that is important for SGM patients. The goal of this article is to empower clinicians to be comfortable discussing issues related to sexuality and gender while also offering resources to learn more, allowing optimal care to be provided to this population. Thus, this article is not comprehensive. There are articles to provide further resources and education, such as the continuing medical education series by Yeung et al10,25 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, as well as organizations within medicine, such as the GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality (https://www.glma.org/), and in dermatology, such as GALDA, the Gay and Lesbian Dermatology Association (https://www.glderm.org/). By providing a safe space for our patients and learning about specific health-related risk factors, dermatologists can provide the best possible care to the LGBT community.

Acknowledgments—I thank Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), and Howa Yeung, MD, MSc (Atlanta, Georgia), for their guidance and mentorship in the creation of this article.

- Jones JM. LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. Gallup website. Published February 24, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx

- U.S. and world population clock. US Census Bureau website. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/popclock/

- National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. LGBTQIA+ glossary of terms for health care teams. Published February 2, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Glossary-2022.02.22-1.pdf

- National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Coordinating Committee. NIH FY 2016-2020 strategic plan to advance research on the health and well-being of sexual and gender minorities. NIH website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.edi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/EDI_Public_files/sgm-strategic-plan.pdf

- Caduceus pin—rainbow. American Medical Student Association website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.amsa.org/member-center/store/Caduceus-Pin-Rainbow-p67375123

- 10 tips for caring for LGBTQIA+ patients. Nurse.org website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://nurse.org/articles/culturally-competent-healthcare-for-LGBTQ-patients/

- Cartron AM, Raiciulescu S, Trinidad JC. Culturally competent care for LGBT patients in dermatology clinics. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:786-787.

- Wareham J. Should you put pronouns in email signatures and social media bios? Forbes website. Published Dec 30, 2019. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiewareham/2020/12/30/should-you-put-pronouns-in-email-signatures-and-social-media-bios/?sh=5b74f1246320

- Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, et al. Healthcare disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1184.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. part II. epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC fact sheet: HIV among gay and bisexual men. CDC website. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-msm-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2016. CDC website. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/CDC_2016_STDS_Report-for508WebSep21_2017_1644.pdf

- Galindo GR, Casey AJ, Yeung A, et al. Community associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among New York City men who have sex with men: qualitative research findings and implications for public health practice. J Community Health. 2012;37:458-467.

- Blashill AJ. Indoor tanning and skin cancer risk among diverse US youth: results from a national sample. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:344-345.

- Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, et al. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:1-17.

- Uaamnuichai S, Panyakhamlerd K, Suwan A, et al. Neovaginal and anal high-risk human papillomavirus DNA among Thai transgender women in gender health clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:547-549.

- Valanis BG, Bowen DJ, Bassford T, et al. Sexual orientation and health: comparisons in the women’s health initiative sample. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:843-853.

- Wierckx K, Van de Peer F, Verhaeghe E, et al. Short- and long-term clinical skin effects of testosterone treatment in trans men. J Sex Med. 2014;11:222-229.

- Turrion-Merino L, Urech-Garcia-de-la-Vega M, Miguel-Gomez L, et al. Severe acne in female-to-male transgender patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1260-1261.

- Questions and answers on the iPLEDGE REMS. US Food and Drug Administration website. Published October 12, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/questions-and-answers-ipledge-rems#:~:text=The%20modification%20will%20become%20effective,verify%20authorization%20to%20dispense%20isotretinoin

- Gao JL, Thoreson N, Dommasch ED. Navigating iPLEDGE enrollment for transgender and gender diverse patients: a guide for providing culturally competent care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:790-791.

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869-3903.

- Garcia-Rodriguez L, Spiegel JH. Melasma in a transgender woman. Am J Otolaryngol. 2018;39:788-790.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian,gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. part I. terminology, demographics, health disparities, and approaches to care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:581-589.

The chances are good that at least one patient you saw today could have been provided a better environment to foster your patient-physician relationship. A 2020 Gallup poll revealed that an estimated 5.6% of US adults identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT).1 Based on the estimated US population of 331.7 million individuals on December 3, 2020, this means that approximately 18.6 million identified as LGBT and could potentially require health care services.2 These numbers highlight the increasing need within the medical community to provide quality and accessible care to the LGBT community, and dermatologists have a role to play. They treat conditions that are apparent to the patient and others around them, attracting those that may not be motivated to see different physicians. They can not only help with skin diseases that affect all patients but also can train other physicians to screen for some dermatologic diseases that may have a higher prevalence within the LGBT community. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to help patients better reflect themselves through both surgical and nonsurgical modalities.

Demographics and Definitions

To discuss this topic effectively, it is important to define LGBT terms (Table).3 As a disclaimer, language is fluid. Despite a word or term currently being used and accepted, it quickly can become obsolete. A clinician can always do research, follow the lead of the patient, and respectfully ask questions if there is ever confusion surrounding terminology. Patients do not expect every physician they encounter to be an expert in this subject. What is most important is that patients are approached with an open mind and humility with the goal of providing optimal care.

Although the federal government now uses the term sexual and gender minorities (SGM), the more specific terms lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender usually are preferred.3,4 Other letters are at times added to the acronym LGBT, including Q for questioning or queer, I for intersex, and A for asexual; all of these letters are under the larger SGM umbrella. Because LGBT is the most commonly used acronym in the daily vernacular, it will be the default for this article.

A term describing sexual orientation does not necessarily describe sexual practices. A woman who identifies as straight may have sex with both men and women, and a gay man may not have sex at all. To be more descriptive regarding sexual practices, one may use the terms men who have sex with men or women who have sex with women.3 Because of this nuance, it is important to elicit a sexual history when speaking to all patients in a forward nonjudgmental manner.

The term transgender is used to describe people whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. Two examples of transgender individuals would be transgender women who were assigned male at birth and transgender men who were assigned female at birth. The term transgender is used in opposition to the term cisgender, which is applied to a person whose gender and sex assigned at birth align.3 When a transgender patient presents to a physician, they may want to discuss methods of gender affirmation or transitioning. These terms encompass any action a person may take to align their body or gender expression with that of the gender they identify with. This could be in the form of gender-affirming hormone therapy (ie, estrogen or testosterone treatment) or gender-affirming surgery (ie, “top” and “bottom” surgeries, in which someone surgically treats their chest or genitals, respectively).3

Creating a Safe Space

The physician is responsible for providing a safe space for patients to disclose medically pertinent information. It is then the job of the dermatologist to be cognizant of health concerns that directly affect the LGBT population and to be prepared if one of these concerns should arise. A safe space consists of both the physical location in which the patient encounter will occur and the people that will be conducting and assisting in the patient encounter. Safe spaces provide a patient with reassurance that they will receive care in a judgement-free location. To create a safe space, both the physical and interpersonal aspects must be addressed to provide an environment that strengthens the patient-physician alliance.

Dermatology residents often spend more time with patients than their attending physicians, providing them the opportunity to foster robust relationships with those served. Although they may not be able to change the physical environment, residents can advocate for patients in their departments and show solidarity in subtle ways. One way to show support for the LGBT community is to publicly display a symbol of solidarity, which could be done by wearing a symbol of support on a white coat lapel. Although there are many designs and styles to choose from, one example is the American Medical Student Association pins that combine the caduceus (a common symbol for medicine) with a rainbow design.5 Whichever symbol is chosen, this small gesture allows patients to immediately know that their physician is an ally. Residents also can encourage their department to add a rainbow flag, a pink triangle, or another symbol somewhere prominent in the check-in area that conveys a message of support.6 Many institutions require residents to perform quality improvement projects. The resident can make a substantial difference in their patients’ experiences by revising their office’s intake forms as a quality improvement project, which can be done by including a section on assigned sex at birth separate from gender.7 When inquiring about gender, in addition to “male” and “female,” a space can be left for people that do not identify with the traditional binary. When asking about sexual orientation, inclusive language options can be provided with additional space for self-identification. Finally, residents can incorporate pronouns below their name in their email signature to normalize this disclosure of information.8 These small changes can have a substantial impact on the health care experience of SGM patients.

Medical Problems Encountered

The previously described changes can be implemented by residents to provide better care to SGM patients, a group usually considered to be more burdened by physical and psychological diseases.9 Furthermore, dermatologists can provide care for these patients in ways that other physicians cannot. There are special considerations for LGBT patients, as some dermatologic conditions may be more common in this patient population.

Prior studies have shown that men who have sex with men have a higher rate of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections, and potentially nonmelanoma skin cancer.10-14 Transgender women also have been found to have higher rates of HIV, in addition to a higher incidence of anal human papillomavirus.15,16 Women who have sex with women have been shown to see physicians less frequently and to be less up to date on their pertinent cancer-related screenings.10,17 Although these associations should not dictate the patient encounter, awareness of them will lead to better patient care. Such awareness also can provide further motivation for dermatologists to discuss safe sexual practices, potential initiation of pre-exposure prophylactic antiretroviral therapy, sun-protective practices, and the importance of following up with a primary physician for examinations and age-specific cancer screening.

Transgender patients may present with unique dermatologic concerns. For transgender male patients, testosterone therapy can cause acne breakouts and androgenetic alopecia. Usually considered worse during the start of treatment, hormone-related acne can be managed with topical retinoids, topical and oral antibiotics, and isotretinoin (if severe).18,19 The iPLEDGE system necessary for prescribing isotretinoin to patients in the United States recently has changed its language to “patients who can get pregnant” and “patients who cannot get pregnant,” following urging by the medical community for inclusivity and progress.20,21 This change creates an inclusive space where registration is no longer centered around gender and instead focuses on the presence of anatomy. Although androgenetic alopecia is a side effect of hormone therapy, it may not be unwanted.18 Discussion about patient desires is important. If the alopecia is unwanted, the Endocrine Society recommends treating cisgender and transgender patients the same in terms of treatment modalities.22

Transgender female patients also can experience dermatologic manifestations of gender-affirming hormone therapy. Melasma may develop secondary to estrogen replacement and can be treated with topical bleaching creams, lasers, and phototherapy.23 Hair removal may be pursued for patients with refractory unwanted body hair, with laser hair removal being the most commonly pursued treatment. Patients also may desire cosmetic procedures, such as botulinum toxin or fillers, to augment their physical appearance.24 Providing these services to patients may allow them to better express themselves and live authentically.

Final Thoughts

There is no way to summarize the experience of everyone within a community. Each person has different thoughts, values, and goals. It also is impossible to encompass every topic that is important for SGM patients. The goal of this article is to empower clinicians to be comfortable discussing issues related to sexuality and gender while also offering resources to learn more, allowing optimal care to be provided to this population. Thus, this article is not comprehensive. There are articles to provide further resources and education, such as the continuing medical education series by Yeung et al10,25 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, as well as organizations within medicine, such as the GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality (https://www.glma.org/), and in dermatology, such as GALDA, the Gay and Lesbian Dermatology Association (https://www.glderm.org/). By providing a safe space for our patients and learning about specific health-related risk factors, dermatologists can provide the best possible care to the LGBT community.

Acknowledgments—I thank Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), and Howa Yeung, MD, MSc (Atlanta, Georgia), for their guidance and mentorship in the creation of this article.

The chances are good that at least one patient you saw today could have been provided a better environment to foster your patient-physician relationship. A 2020 Gallup poll revealed that an estimated 5.6% of US adults identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT).1 Based on the estimated US population of 331.7 million individuals on December 3, 2020, this means that approximately 18.6 million identified as LGBT and could potentially require health care services.2 These numbers highlight the increasing need within the medical community to provide quality and accessible care to the LGBT community, and dermatologists have a role to play. They treat conditions that are apparent to the patient and others around them, attracting those that may not be motivated to see different physicians. They can not only help with skin diseases that affect all patients but also can train other physicians to screen for some dermatologic diseases that may have a higher prevalence within the LGBT community. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to help patients better reflect themselves through both surgical and nonsurgical modalities.

Demographics and Definitions

To discuss this topic effectively, it is important to define LGBT terms (Table).3 As a disclaimer, language is fluid. Despite a word or term currently being used and accepted, it quickly can become obsolete. A clinician can always do research, follow the lead of the patient, and respectfully ask questions if there is ever confusion surrounding terminology. Patients do not expect every physician they encounter to be an expert in this subject. What is most important is that patients are approached with an open mind and humility with the goal of providing optimal care.

Although the federal government now uses the term sexual and gender minorities (SGM), the more specific terms lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender usually are preferred.3,4 Other letters are at times added to the acronym LGBT, including Q for questioning or queer, I for intersex, and A for asexual; all of these letters are under the larger SGM umbrella. Because LGBT is the most commonly used acronym in the daily vernacular, it will be the default for this article.

A term describing sexual orientation does not necessarily describe sexual practices. A woman who identifies as straight may have sex with both men and women, and a gay man may not have sex at all. To be more descriptive regarding sexual practices, one may use the terms men who have sex with men or women who have sex with women.3 Because of this nuance, it is important to elicit a sexual history when speaking to all patients in a forward nonjudgmental manner.

The term transgender is used to describe people whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. Two examples of transgender individuals would be transgender women who were assigned male at birth and transgender men who were assigned female at birth. The term transgender is used in opposition to the term cisgender, which is applied to a person whose gender and sex assigned at birth align.3 When a transgender patient presents to a physician, they may want to discuss methods of gender affirmation or transitioning. These terms encompass any action a person may take to align their body or gender expression with that of the gender they identify with. This could be in the form of gender-affirming hormone therapy (ie, estrogen or testosterone treatment) or gender-affirming surgery (ie, “top” and “bottom” surgeries, in which someone surgically treats their chest or genitals, respectively).3

Creating a Safe Space

The physician is responsible for providing a safe space for patients to disclose medically pertinent information. It is then the job of the dermatologist to be cognizant of health concerns that directly affect the LGBT population and to be prepared if one of these concerns should arise. A safe space consists of both the physical location in which the patient encounter will occur and the people that will be conducting and assisting in the patient encounter. Safe spaces provide a patient with reassurance that they will receive care in a judgement-free location. To create a safe space, both the physical and interpersonal aspects must be addressed to provide an environment that strengthens the patient-physician alliance.

Dermatology residents often spend more time with patients than their attending physicians, providing them the opportunity to foster robust relationships with those served. Although they may not be able to change the physical environment, residents can advocate for patients in their departments and show solidarity in subtle ways. One way to show support for the LGBT community is to publicly display a symbol of solidarity, which could be done by wearing a symbol of support on a white coat lapel. Although there are many designs and styles to choose from, one example is the American Medical Student Association pins that combine the caduceus (a common symbol for medicine) with a rainbow design.5 Whichever symbol is chosen, this small gesture allows patients to immediately know that their physician is an ally. Residents also can encourage their department to add a rainbow flag, a pink triangle, or another symbol somewhere prominent in the check-in area that conveys a message of support.6 Many institutions require residents to perform quality improvement projects. The resident can make a substantial difference in their patients’ experiences by revising their office’s intake forms as a quality improvement project, which can be done by including a section on assigned sex at birth separate from gender.7 When inquiring about gender, in addition to “male” and “female,” a space can be left for people that do not identify with the traditional binary. When asking about sexual orientation, inclusive language options can be provided with additional space for self-identification. Finally, residents can incorporate pronouns below their name in their email signature to normalize this disclosure of information.8 These small changes can have a substantial impact on the health care experience of SGM patients.

Medical Problems Encountered

The previously described changes can be implemented by residents to provide better care to SGM patients, a group usually considered to be more burdened by physical and psychological diseases.9 Furthermore, dermatologists can provide care for these patients in ways that other physicians cannot. There are special considerations for LGBT patients, as some dermatologic conditions may be more common in this patient population.

Prior studies have shown that men who have sex with men have a higher rate of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections, and potentially nonmelanoma skin cancer.10-14 Transgender women also have been found to have higher rates of HIV, in addition to a higher incidence of anal human papillomavirus.15,16 Women who have sex with women have been shown to see physicians less frequently and to be less up to date on their pertinent cancer-related screenings.10,17 Although these associations should not dictate the patient encounter, awareness of them will lead to better patient care. Such awareness also can provide further motivation for dermatologists to discuss safe sexual practices, potential initiation of pre-exposure prophylactic antiretroviral therapy, sun-protective practices, and the importance of following up with a primary physician for examinations and age-specific cancer screening.

Transgender patients may present with unique dermatologic concerns. For transgender male patients, testosterone therapy can cause acne breakouts and androgenetic alopecia. Usually considered worse during the start of treatment, hormone-related acne can be managed with topical retinoids, topical and oral antibiotics, and isotretinoin (if severe).18,19 The iPLEDGE system necessary for prescribing isotretinoin to patients in the United States recently has changed its language to “patients who can get pregnant” and “patients who cannot get pregnant,” following urging by the medical community for inclusivity and progress.20,21 This change creates an inclusive space where registration is no longer centered around gender and instead focuses on the presence of anatomy. Although androgenetic alopecia is a side effect of hormone therapy, it may not be unwanted.18 Discussion about patient desires is important. If the alopecia is unwanted, the Endocrine Society recommends treating cisgender and transgender patients the same in terms of treatment modalities.22

Transgender female patients also can experience dermatologic manifestations of gender-affirming hormone therapy. Melasma may develop secondary to estrogen replacement and can be treated with topical bleaching creams, lasers, and phototherapy.23 Hair removal may be pursued for patients with refractory unwanted body hair, with laser hair removal being the most commonly pursued treatment. Patients also may desire cosmetic procedures, such as botulinum toxin or fillers, to augment their physical appearance.24 Providing these services to patients may allow them to better express themselves and live authentically.

Final Thoughts

There is no way to summarize the experience of everyone within a community. Each person has different thoughts, values, and goals. It also is impossible to encompass every topic that is important for SGM patients. The goal of this article is to empower clinicians to be comfortable discussing issues related to sexuality and gender while also offering resources to learn more, allowing optimal care to be provided to this population. Thus, this article is not comprehensive. There are articles to provide further resources and education, such as the continuing medical education series by Yeung et al10,25 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, as well as organizations within medicine, such as the GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality (https://www.glma.org/), and in dermatology, such as GALDA, the Gay and Lesbian Dermatology Association (https://www.glderm.org/). By providing a safe space for our patients and learning about specific health-related risk factors, dermatologists can provide the best possible care to the LGBT community.

Acknowledgments—I thank Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), and Howa Yeung, MD, MSc (Atlanta, Georgia), for their guidance and mentorship in the creation of this article.

- Jones JM. LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. Gallup website. Published February 24, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx

- U.S. and world population clock. US Census Bureau website. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/popclock/

- National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. LGBTQIA+ glossary of terms for health care teams. Published February 2, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Glossary-2022.02.22-1.pdf

- National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Coordinating Committee. NIH FY 2016-2020 strategic plan to advance research on the health and well-being of sexual and gender minorities. NIH website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.edi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/EDI_Public_files/sgm-strategic-plan.pdf

- Caduceus pin—rainbow. American Medical Student Association website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.amsa.org/member-center/store/Caduceus-Pin-Rainbow-p67375123

- 10 tips for caring for LGBTQIA+ patients. Nurse.org website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://nurse.org/articles/culturally-competent-healthcare-for-LGBTQ-patients/

- Cartron AM, Raiciulescu S, Trinidad JC. Culturally competent care for LGBT patients in dermatology clinics. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:786-787.

- Wareham J. Should you put pronouns in email signatures and social media bios? Forbes website. Published Dec 30, 2019. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiewareham/2020/12/30/should-you-put-pronouns-in-email-signatures-and-social-media-bios/?sh=5b74f1246320

- Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, et al. Healthcare disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1184.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. part II. epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC fact sheet: HIV among gay and bisexual men. CDC website. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-msm-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2016. CDC website. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/CDC_2016_STDS_Report-for508WebSep21_2017_1644.pdf

- Galindo GR, Casey AJ, Yeung A, et al. Community associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among New York City men who have sex with men: qualitative research findings and implications for public health practice. J Community Health. 2012;37:458-467.

- Blashill AJ. Indoor tanning and skin cancer risk among diverse US youth: results from a national sample. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:344-345.

- Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, et al. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:1-17.

- Uaamnuichai S, Panyakhamlerd K, Suwan A, et al. Neovaginal and anal high-risk human papillomavirus DNA among Thai transgender women in gender health clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:547-549.

- Valanis BG, Bowen DJ, Bassford T, et al. Sexual orientation and health: comparisons in the women’s health initiative sample. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:843-853.

- Wierckx K, Van de Peer F, Verhaeghe E, et al. Short- and long-term clinical skin effects of testosterone treatment in trans men. J Sex Med. 2014;11:222-229.

- Turrion-Merino L, Urech-Garcia-de-la-Vega M, Miguel-Gomez L, et al. Severe acne in female-to-male transgender patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1260-1261.

- Questions and answers on the iPLEDGE REMS. US Food and Drug Administration website. Published October 12, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/questions-and-answers-ipledge-rems#:~:text=The%20modification%20will%20become%20effective,verify%20authorization%20to%20dispense%20isotretinoin

- Gao JL, Thoreson N, Dommasch ED. Navigating iPLEDGE enrollment for transgender and gender diverse patients: a guide for providing culturally competent care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:790-791.

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869-3903.

- Garcia-Rodriguez L, Spiegel JH. Melasma in a transgender woman. Am J Otolaryngol. 2018;39:788-790.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian,gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. part I. terminology, demographics, health disparities, and approaches to care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:581-589.

- Jones JM. LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. Gallup website. Published February 24, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx

- U.S. and world population clock. US Census Bureau website. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/popclock/

- National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. LGBTQIA+ glossary of terms for health care teams. Published February 2, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Glossary-2022.02.22-1.pdf

- National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Coordinating Committee. NIH FY 2016-2020 strategic plan to advance research on the health and well-being of sexual and gender minorities. NIH website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.edi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/EDI_Public_files/sgm-strategic-plan.pdf

- Caduceus pin—rainbow. American Medical Student Association website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.amsa.org/member-center/store/Caduceus-Pin-Rainbow-p67375123

- 10 tips for caring for LGBTQIA+ patients. Nurse.org website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://nurse.org/articles/culturally-competent-healthcare-for-LGBTQ-patients/

- Cartron AM, Raiciulescu S, Trinidad JC. Culturally competent care for LGBT patients in dermatology clinics. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:786-787.

- Wareham J. Should you put pronouns in email signatures and social media bios? Forbes website. Published Dec 30, 2019. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiewareham/2020/12/30/should-you-put-pronouns-in-email-signatures-and-social-media-bios/?sh=5b74f1246320

- Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, et al. Healthcare disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1184.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. part II. epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC fact sheet: HIV among gay and bisexual men. CDC website. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-msm-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2016. CDC website. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/CDC_2016_STDS_Report-for508WebSep21_2017_1644.pdf

- Galindo GR, Casey AJ, Yeung A, et al. Community associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among New York City men who have sex with men: qualitative research findings and implications for public health practice. J Community Health. 2012;37:458-467.

- Blashill AJ. Indoor tanning and skin cancer risk among diverse US youth: results from a national sample. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:344-345.

- Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, et al. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:1-17.

- Uaamnuichai S, Panyakhamlerd K, Suwan A, et al. Neovaginal and anal high-risk human papillomavirus DNA among Thai transgender women in gender health clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:547-549.

- Valanis BG, Bowen DJ, Bassford T, et al. Sexual orientation and health: comparisons in the women’s health initiative sample. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:843-853.

- Wierckx K, Van de Peer F, Verhaeghe E, et al. Short- and long-term clinical skin effects of testosterone treatment in trans men. J Sex Med. 2014;11:222-229.

- Turrion-Merino L, Urech-Garcia-de-la-Vega M, Miguel-Gomez L, et al. Severe acne in female-to-male transgender patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1260-1261.

- Questions and answers on the iPLEDGE REMS. US Food and Drug Administration website. Published October 12, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/questions-and-answers-ipledge-rems#:~:text=The%20modification%20will%20become%20effective,verify%20authorization%20to%20dispense%20isotretinoin

- Gao JL, Thoreson N, Dommasch ED. Navigating iPLEDGE enrollment for transgender and gender diverse patients: a guide for providing culturally competent care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:790-791.

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869-3903.

- Garcia-Rodriguez L, Spiegel JH. Melasma in a transgender woman. Am J Otolaryngol. 2018;39:788-790.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian,gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. part I. terminology, demographics, health disparities, and approaches to care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:581-589.

Resident Pearl

- Because of the longitudinal relationships dermatology residents make with their patients, they have a unique opportunity to provide a safe space and life-changing care to patients within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community.