User login

A 19-month-old boy comes to the office with a large firm erythematous swelling of his anterior left thigh that reaches from just below the inguinal crease to the patella. He got his routine immunizations 2 days prior to this visit including the fourth DTaP dose in his left thigh. Clinicians who care for children and who give routine immunizations occasionally see such an adverse effect following immunization (AEFI). These large local reactions have been described for many decades and occur after many vaccines.

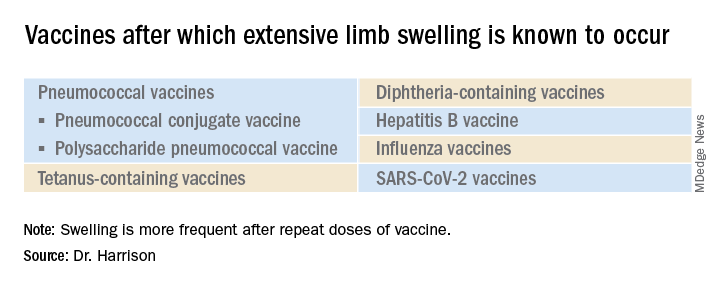

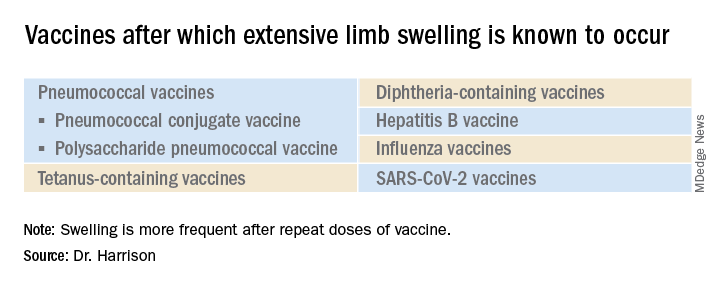

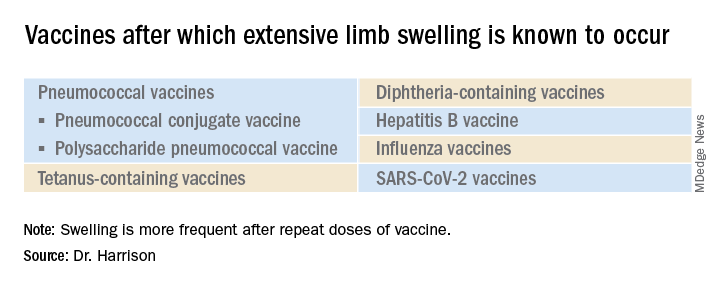

What is extensive limb swelling (ELS)? ELS is defined as erythema/swelling crossing a joint or extending mostly joint to joint. It is a subset of large local AEFIs. ELS is generally firm and often erythematous with varying degrees of pain. ELS is now most frequent after pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) and DTaP, with a 1%-4% rate after DTaP boosters.1-3 ELS and other large local swelling reactions occur at nearly any age.1 And yet there is still much that is not known about their true pathogenesis. Likewise, there are no accurate predictors of which vaccinees will develop large inflammatory processes at or near the site of immunization.

ELS after standard vaccines

The largest report to date on AEFI of all ages, including ELS, covered 1990-2003.1 Two upfront caveats are: This study evaluated ELS before PCVs were available, and in adults, repeat 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine was the most common cause of ELS in this study, comprising 45% of all adult ELS.

Considering all ages, ELS onset was nearly always greater than 1 hour and was less than 24 hours post vaccine in almost 75% of patients. However, for those aged under 2 years, onset in less than 24 hours was even more frequent (84%). Interestingly, concomitant fever occurred in less than 25% regardless of age. In adults, ELS after tetanus- and diphtheria-containing vaccines occurred mostly in women (75%); whereas for ELS under 8 years of age, males predominated (about 60%). Of note, tetanus- and diphtheria-containing vaccines were the most frequent ELS-inducing vaccines in children, that is, 75% aged under 8 years and 55% for those aged 8-17 years. Focusing on pediatric ELS after DTaP by dose, 33% were after the fourth, 31% after the fifth, 12% after the second, 10% after the first, and 3% after the third dose. In the case above, ELS was after the fourth dose.

Clinicians caring for children know how to manage ELS after DTaP or PCVs. They understand that ELS looks scary and is uncomfortable but is not dangerous and requires no specific treatment. Supportive management, that is, pain reliever, cool compresses, and TLC, are warranted. ELS is not a contraindication to subsequent immunization with the same vaccine. That said, large local reactions or ELS do occur with subsequent doses of that same vaccine at varying rates up to 66% of the time. Management is the same with repeat episodes, and no sequelae are expected. Supportive management only is standard unless one suspects a very rare Arthus reaction. If central necrosis occurs or swelling evolution/resolution is not per expectations, referral to a vaccine expert can sort out if it is an Arthus reaction, in which case, subsequent use of the same vaccine in not recommended.

ELS and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

With SARS-CoV-2 vaccines now authorized for adolescents and expected in a few months for younger children, large local AEFI reactions related to pediatric SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are expected, given that “COVID arm” is now well described in adults.4 Overall, ELS/large local reactions have been reported more frequently with the Moderna than Pfizer mRNA vaccine.4 In the almost 42% of adults having ELS post first dose, repeat ELS post second dose often appears sooner but also resolves more quickly, with no known sequelae.5

Some biopsies have shown delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (DTH) (superficial perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrates with rare eosinophils and scattered mast cells),6,7 while others show no DTH but these patients have findings of immediate hypersensitivity findings and negative skin testing to the vaccine.8 With regard to sex, Dutch ELS data in White adults reveal 90% occur in females – higher than the 75% female rate after standard vaccines.7 Onset of ELS data show that Pfizer mRNA vaccinees had onset on average at 38 hours (range, <1 hr to 12 days). Boston data mostly in White adults reveal later onset (median, 6 days; range, 2-12 days).4 In contrast, adults of color appear to have later onset (mean, 8 days; range, 4-14 days).9

In addition to the local swelling, patients had concurrent injection-site AEFIs of pain (65%), warmth (63%), and pruritus (26%), plus myalgia (51%), headache (48%), malaise (45%), fatigue (43%), chills (33%), arthralgia (30%), and fever (28%).7

What should we tell families about pediatric ELS before we give SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to children? Clinical pediatric SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trials are smaller “immunologic bridging” studies, not requiring proof of efficacy. So, the precise incidence of pediatric ELS (adult rate is estimated under 1/100,000) may not be known until months after general use. Nevertheless, part of our counseling of families will need to include ELS/large local reactions. Unless new data show otherwise, the spiel that clinicians have developed to counsel about the rare chance of ELS after routine vaccines should also be useful to inform families of the rare chance of ELS post SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

The bottom line is that the management of pediatric ELS after SARS-CoV-2 vaccines should be the same as after standard vaccines. And remember, whether the reactions are DTH or not, neither immediate local injection-site reactions nor DTH reactions are contraindications to subsequent vaccination unless anaphylaxis or Arthus reaction is suspected.10,11

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Woo EJ and the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System Working Group. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:351-8.

2. Rennels MB et al. Pediatrics 2000;105:e12.

3. Huber BM, Goetschel P. J Pediatr. 2011;158:1033.

4. Blumenthal KG et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1273-7.

5. McMahon DE et al. J Amer Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(1):46-55. 6. Johnston MS et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(6):716-20 .

7. ELS associated with the administration of Comirnaty®. WHO database Vigilyze (cited 2021 Feb 22). Available from https://vigilyze.who-umc.org/.

8. Baeck M et al. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2104751.

9. Samarakoon U et al. N Eng J Med. 2021 Jun 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2108620.

10. Kelso JM et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:25-43.

11. Zafack JG et al. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20163707.

A 19-month-old boy comes to the office with a large firm erythematous swelling of his anterior left thigh that reaches from just below the inguinal crease to the patella. He got his routine immunizations 2 days prior to this visit including the fourth DTaP dose in his left thigh. Clinicians who care for children and who give routine immunizations occasionally see such an adverse effect following immunization (AEFI). These large local reactions have been described for many decades and occur after many vaccines.

What is extensive limb swelling (ELS)? ELS is defined as erythema/swelling crossing a joint or extending mostly joint to joint. It is a subset of large local AEFIs. ELS is generally firm and often erythematous with varying degrees of pain. ELS is now most frequent after pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) and DTaP, with a 1%-4% rate after DTaP boosters.1-3 ELS and other large local swelling reactions occur at nearly any age.1 And yet there is still much that is not known about their true pathogenesis. Likewise, there are no accurate predictors of which vaccinees will develop large inflammatory processes at or near the site of immunization.

ELS after standard vaccines

The largest report to date on AEFI of all ages, including ELS, covered 1990-2003.1 Two upfront caveats are: This study evaluated ELS before PCVs were available, and in adults, repeat 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine was the most common cause of ELS in this study, comprising 45% of all adult ELS.

Considering all ages, ELS onset was nearly always greater than 1 hour and was less than 24 hours post vaccine in almost 75% of patients. However, for those aged under 2 years, onset in less than 24 hours was even more frequent (84%). Interestingly, concomitant fever occurred in less than 25% regardless of age. In adults, ELS after tetanus- and diphtheria-containing vaccines occurred mostly in women (75%); whereas for ELS under 8 years of age, males predominated (about 60%). Of note, tetanus- and diphtheria-containing vaccines were the most frequent ELS-inducing vaccines in children, that is, 75% aged under 8 years and 55% for those aged 8-17 years. Focusing on pediatric ELS after DTaP by dose, 33% were after the fourth, 31% after the fifth, 12% after the second, 10% after the first, and 3% after the third dose. In the case above, ELS was after the fourth dose.

Clinicians caring for children know how to manage ELS after DTaP or PCVs. They understand that ELS looks scary and is uncomfortable but is not dangerous and requires no specific treatment. Supportive management, that is, pain reliever, cool compresses, and TLC, are warranted. ELS is not a contraindication to subsequent immunization with the same vaccine. That said, large local reactions or ELS do occur with subsequent doses of that same vaccine at varying rates up to 66% of the time. Management is the same with repeat episodes, and no sequelae are expected. Supportive management only is standard unless one suspects a very rare Arthus reaction. If central necrosis occurs or swelling evolution/resolution is not per expectations, referral to a vaccine expert can sort out if it is an Arthus reaction, in which case, subsequent use of the same vaccine in not recommended.

ELS and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

With SARS-CoV-2 vaccines now authorized for adolescents and expected in a few months for younger children, large local AEFI reactions related to pediatric SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are expected, given that “COVID arm” is now well described in adults.4 Overall, ELS/large local reactions have been reported more frequently with the Moderna than Pfizer mRNA vaccine.4 In the almost 42% of adults having ELS post first dose, repeat ELS post second dose often appears sooner but also resolves more quickly, with no known sequelae.5

Some biopsies have shown delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (DTH) (superficial perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrates with rare eosinophils and scattered mast cells),6,7 while others show no DTH but these patients have findings of immediate hypersensitivity findings and negative skin testing to the vaccine.8 With regard to sex, Dutch ELS data in White adults reveal 90% occur in females – higher than the 75% female rate after standard vaccines.7 Onset of ELS data show that Pfizer mRNA vaccinees had onset on average at 38 hours (range, <1 hr to 12 days). Boston data mostly in White adults reveal later onset (median, 6 days; range, 2-12 days).4 In contrast, adults of color appear to have later onset (mean, 8 days; range, 4-14 days).9

In addition to the local swelling, patients had concurrent injection-site AEFIs of pain (65%), warmth (63%), and pruritus (26%), plus myalgia (51%), headache (48%), malaise (45%), fatigue (43%), chills (33%), arthralgia (30%), and fever (28%).7

What should we tell families about pediatric ELS before we give SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to children? Clinical pediatric SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trials are smaller “immunologic bridging” studies, not requiring proof of efficacy. So, the precise incidence of pediatric ELS (adult rate is estimated under 1/100,000) may not be known until months after general use. Nevertheless, part of our counseling of families will need to include ELS/large local reactions. Unless new data show otherwise, the spiel that clinicians have developed to counsel about the rare chance of ELS after routine vaccines should also be useful to inform families of the rare chance of ELS post SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

The bottom line is that the management of pediatric ELS after SARS-CoV-2 vaccines should be the same as after standard vaccines. And remember, whether the reactions are DTH or not, neither immediate local injection-site reactions nor DTH reactions are contraindications to subsequent vaccination unless anaphylaxis or Arthus reaction is suspected.10,11

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Woo EJ and the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System Working Group. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:351-8.

2. Rennels MB et al. Pediatrics 2000;105:e12.

3. Huber BM, Goetschel P. J Pediatr. 2011;158:1033.

4. Blumenthal KG et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1273-7.

5. McMahon DE et al. J Amer Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(1):46-55. 6. Johnston MS et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(6):716-20 .

7. ELS associated with the administration of Comirnaty®. WHO database Vigilyze (cited 2021 Feb 22). Available from https://vigilyze.who-umc.org/.

8. Baeck M et al. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2104751.

9. Samarakoon U et al. N Eng J Med. 2021 Jun 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2108620.

10. Kelso JM et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:25-43.

11. Zafack JG et al. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20163707.

A 19-month-old boy comes to the office with a large firm erythematous swelling of his anterior left thigh that reaches from just below the inguinal crease to the patella. He got his routine immunizations 2 days prior to this visit including the fourth DTaP dose in his left thigh. Clinicians who care for children and who give routine immunizations occasionally see such an adverse effect following immunization (AEFI). These large local reactions have been described for many decades and occur after many vaccines.

What is extensive limb swelling (ELS)? ELS is defined as erythema/swelling crossing a joint or extending mostly joint to joint. It is a subset of large local AEFIs. ELS is generally firm and often erythematous with varying degrees of pain. ELS is now most frequent after pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) and DTaP, with a 1%-4% rate after DTaP boosters.1-3 ELS and other large local swelling reactions occur at nearly any age.1 And yet there is still much that is not known about their true pathogenesis. Likewise, there are no accurate predictors of which vaccinees will develop large inflammatory processes at or near the site of immunization.

ELS after standard vaccines

The largest report to date on AEFI of all ages, including ELS, covered 1990-2003.1 Two upfront caveats are: This study evaluated ELS before PCVs were available, and in adults, repeat 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine was the most common cause of ELS in this study, comprising 45% of all adult ELS.

Considering all ages, ELS onset was nearly always greater than 1 hour and was less than 24 hours post vaccine in almost 75% of patients. However, for those aged under 2 years, onset in less than 24 hours was even more frequent (84%). Interestingly, concomitant fever occurred in less than 25% regardless of age. In adults, ELS after tetanus- and diphtheria-containing vaccines occurred mostly in women (75%); whereas for ELS under 8 years of age, males predominated (about 60%). Of note, tetanus- and diphtheria-containing vaccines were the most frequent ELS-inducing vaccines in children, that is, 75% aged under 8 years and 55% for those aged 8-17 years. Focusing on pediatric ELS after DTaP by dose, 33% were after the fourth, 31% after the fifth, 12% after the second, 10% after the first, and 3% after the third dose. In the case above, ELS was after the fourth dose.

Clinicians caring for children know how to manage ELS after DTaP or PCVs. They understand that ELS looks scary and is uncomfortable but is not dangerous and requires no specific treatment. Supportive management, that is, pain reliever, cool compresses, and TLC, are warranted. ELS is not a contraindication to subsequent immunization with the same vaccine. That said, large local reactions or ELS do occur with subsequent doses of that same vaccine at varying rates up to 66% of the time. Management is the same with repeat episodes, and no sequelae are expected. Supportive management only is standard unless one suspects a very rare Arthus reaction. If central necrosis occurs or swelling evolution/resolution is not per expectations, referral to a vaccine expert can sort out if it is an Arthus reaction, in which case, subsequent use of the same vaccine in not recommended.

ELS and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

With SARS-CoV-2 vaccines now authorized for adolescents and expected in a few months for younger children, large local AEFI reactions related to pediatric SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are expected, given that “COVID arm” is now well described in adults.4 Overall, ELS/large local reactions have been reported more frequently with the Moderna than Pfizer mRNA vaccine.4 In the almost 42% of adults having ELS post first dose, repeat ELS post second dose often appears sooner but also resolves more quickly, with no known sequelae.5

Some biopsies have shown delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (DTH) (superficial perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrates with rare eosinophils and scattered mast cells),6,7 while others show no DTH but these patients have findings of immediate hypersensitivity findings and negative skin testing to the vaccine.8 With regard to sex, Dutch ELS data in White adults reveal 90% occur in females – higher than the 75% female rate after standard vaccines.7 Onset of ELS data show that Pfizer mRNA vaccinees had onset on average at 38 hours (range, <1 hr to 12 days). Boston data mostly in White adults reveal later onset (median, 6 days; range, 2-12 days).4 In contrast, adults of color appear to have later onset (mean, 8 days; range, 4-14 days).9

In addition to the local swelling, patients had concurrent injection-site AEFIs of pain (65%), warmth (63%), and pruritus (26%), plus myalgia (51%), headache (48%), malaise (45%), fatigue (43%), chills (33%), arthralgia (30%), and fever (28%).7

What should we tell families about pediatric ELS before we give SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to children? Clinical pediatric SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trials are smaller “immunologic bridging” studies, not requiring proof of efficacy. So, the precise incidence of pediatric ELS (adult rate is estimated under 1/100,000) may not be known until months after general use. Nevertheless, part of our counseling of families will need to include ELS/large local reactions. Unless new data show otherwise, the spiel that clinicians have developed to counsel about the rare chance of ELS after routine vaccines should also be useful to inform families of the rare chance of ELS post SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

The bottom line is that the management of pediatric ELS after SARS-CoV-2 vaccines should be the same as after standard vaccines. And remember, whether the reactions are DTH or not, neither immediate local injection-site reactions nor DTH reactions are contraindications to subsequent vaccination unless anaphylaxis or Arthus reaction is suspected.10,11

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Woo EJ and the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System Working Group. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:351-8.

2. Rennels MB et al. Pediatrics 2000;105:e12.

3. Huber BM, Goetschel P. J Pediatr. 2011;158:1033.

4. Blumenthal KG et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1273-7.

5. McMahon DE et al. J Amer Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(1):46-55. 6. Johnston MS et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(6):716-20 .

7. ELS associated with the administration of Comirnaty®. WHO database Vigilyze (cited 2021 Feb 22). Available from https://vigilyze.who-umc.org/.

8. Baeck M et al. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2104751.

9. Samarakoon U et al. N Eng J Med. 2021 Jun 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2108620.

10. Kelso JM et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:25-43.

11. Zafack JG et al. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20163707.