User login

Background

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a life-threatening condition, with a high mortality rate in undiagnosed cases. Several studies have shown that emergency physicians (EPs) can accurately diagnose an AAA through bedside ultrasound. This examination, which takes approximately 1 to 2 minutes, is easy to learn, perform, and interpret. In cases of a ruptured aneurysm, where minutes matter, this modality can significantly decrease time to diagnosis and expedite surgical consultation and repair.

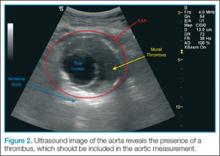

To perform the scan, the clinician should use a curvilinear (abdominal) probe with the marker pointed toward the patient’s right side. The probe should be placed just caudal to the xiphoid process in a transverse orientation. To locate the aorta, the “spine shadow” should first be identified for orientation. Vertebral bodies will have a bright rounded white cortex anterior to a dark shadow (Figure 1). The aorta is circular in shape, pulsatile, and lies just anterior to the spine. Care should be taken not to confuse the aorta with the inferior vena cava (IVC), which can also be seen in this view. The IVC is located to the right of the spine (in this orientation, it will be seen on the left side of the clinician’s image). The IVC has a thinner wall and is typically more oval in shape than the aorta.

Once the aorta is visualized, the clinician should slide the probe caudally while keeping the aorta in the center of the screen. The celiac trunk will be initially visualized as the probe is moved, and the superior mesenteric artery will be superior caudal to the celiac trunk. The clinician should then continue to move the probe down caudally until the bifurcation, which is typically found just above the level of the umbilicus, is visualized. It is especially important to visualize the distal (infrarenal) aorta just above the bifurcation since this is where most AAAs occur.

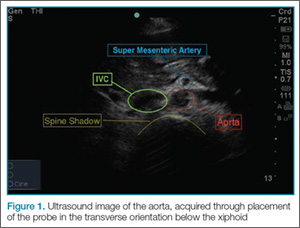

A normal aorta caliber will measure less than 3 cm in diameter, and the common iliac vessels should measure half of that diameter (1.5 cm in adult women, 1.85 cm in adult men). Since the entire diameter of aorta that predicts the risk of rupture, it is critical that measurements include any thrombus present (Figure 2).

Once the entire aorta and bifurcation is seen in cross-section, the probe should be rotated clockwise 90 degrees so that the indicator marker is pointed toward the patient’s head; this will allow a longitudinal view of the aorta (Figure 3). When scanning longitudinally, it is important to place the probe over the center of the aorta as any lateral movement will cause the aorta to appear smaller than its actual size.

Points and Tips to Remember

To ensure the scan is performed correctly, it is essential to begin at the xiphoid process and then proceed caudally—without lifting the transducer off the patient. This will ensure the entire aorta is visualized, which is necessary to rule out an AAA.

During evaluation, bowel gas can obscure the image. If this occurs, the clinician should first try increasing the transducer pressure gradually or moving the probe back and forth while applying pressure in an attempt to displace the bowel gas. If this technique is unsuccessful, scanning off the midline or angling the probe may capture the aorta. Alternatively, a coronal image can be obtained by placing the probe on the patient’s right side in the midaxillary line with the indicator marker pointing toward the head.

Limitations

Despite the high sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting AAAs, there are some limitations to its use. Since the majority of AAAs rupture into the retroperitoneum, a rupture or leak is difficult to visualize on ultrasound. The EP should therefore recognize that the presence of an aneurysm alone in the setting of a convincing clinical history is sufficient to make the diagnosis.

Conclusion

Prompt evaluation and management of patients presenting with a suspected AAA are essential to avoid rupture, a catastrophic event with an extremely high-mortality rate. When the proper techniques for visualization are employed, including proper measurement of the aorta, bedside ultrasound is highly sensitive and specific for detecting an AAA.

Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

Background

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a life-threatening condition, with a high mortality rate in undiagnosed cases. Several studies have shown that emergency physicians (EPs) can accurately diagnose an AAA through bedside ultrasound. This examination, which takes approximately 1 to 2 minutes, is easy to learn, perform, and interpret. In cases of a ruptured aneurysm, where minutes matter, this modality can significantly decrease time to diagnosis and expedite surgical consultation and repair.

To perform the scan, the clinician should use a curvilinear (abdominal) probe with the marker pointed toward the patient’s right side. The probe should be placed just caudal to the xiphoid process in a transverse orientation. To locate the aorta, the “spine shadow” should first be identified for orientation. Vertebral bodies will have a bright rounded white cortex anterior to a dark shadow (Figure 1). The aorta is circular in shape, pulsatile, and lies just anterior to the spine. Care should be taken not to confuse the aorta with the inferior vena cava (IVC), which can also be seen in this view. The IVC is located to the right of the spine (in this orientation, it will be seen on the left side of the clinician’s image). The IVC has a thinner wall and is typically more oval in shape than the aorta.

Once the aorta is visualized, the clinician should slide the probe caudally while keeping the aorta in the center of the screen. The celiac trunk will be initially visualized as the probe is moved, and the superior mesenteric artery will be superior caudal to the celiac trunk. The clinician should then continue to move the probe down caudally until the bifurcation, which is typically found just above the level of the umbilicus, is visualized. It is especially important to visualize the distal (infrarenal) aorta just above the bifurcation since this is where most AAAs occur.

A normal aorta caliber will measure less than 3 cm in diameter, and the common iliac vessels should measure half of that diameter (1.5 cm in adult women, 1.85 cm in adult men). Since the entire diameter of aorta that predicts the risk of rupture, it is critical that measurements include any thrombus present (Figure 2).

Once the entire aorta and bifurcation is seen in cross-section, the probe should be rotated clockwise 90 degrees so that the indicator marker is pointed toward the patient’s head; this will allow a longitudinal view of the aorta (Figure 3). When scanning longitudinally, it is important to place the probe over the center of the aorta as any lateral movement will cause the aorta to appear smaller than its actual size.

Points and Tips to Remember

To ensure the scan is performed correctly, it is essential to begin at the xiphoid process and then proceed caudally—without lifting the transducer off the patient. This will ensure the entire aorta is visualized, which is necessary to rule out an AAA.

During evaluation, bowel gas can obscure the image. If this occurs, the clinician should first try increasing the transducer pressure gradually or moving the probe back and forth while applying pressure in an attempt to displace the bowel gas. If this technique is unsuccessful, scanning off the midline or angling the probe may capture the aorta. Alternatively, a coronal image can be obtained by placing the probe on the patient’s right side in the midaxillary line with the indicator marker pointing toward the head.

Limitations

Despite the high sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting AAAs, there are some limitations to its use. Since the majority of AAAs rupture into the retroperitoneum, a rupture or leak is difficult to visualize on ultrasound. The EP should therefore recognize that the presence of an aneurysm alone in the setting of a convincing clinical history is sufficient to make the diagnosis.

Conclusion

Prompt evaluation and management of patients presenting with a suspected AAA are essential to avoid rupture, a catastrophic event with an extremely high-mortality rate. When the proper techniques for visualization are employed, including proper measurement of the aorta, bedside ultrasound is highly sensitive and specific for detecting an AAA.

Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

Background

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a life-threatening condition, with a high mortality rate in undiagnosed cases. Several studies have shown that emergency physicians (EPs) can accurately diagnose an AAA through bedside ultrasound. This examination, which takes approximately 1 to 2 minutes, is easy to learn, perform, and interpret. In cases of a ruptured aneurysm, where minutes matter, this modality can significantly decrease time to diagnosis and expedite surgical consultation and repair.

To perform the scan, the clinician should use a curvilinear (abdominal) probe with the marker pointed toward the patient’s right side. The probe should be placed just caudal to the xiphoid process in a transverse orientation. To locate the aorta, the “spine shadow” should first be identified for orientation. Vertebral bodies will have a bright rounded white cortex anterior to a dark shadow (Figure 1). The aorta is circular in shape, pulsatile, and lies just anterior to the spine. Care should be taken not to confuse the aorta with the inferior vena cava (IVC), which can also be seen in this view. The IVC is located to the right of the spine (in this orientation, it will be seen on the left side of the clinician’s image). The IVC has a thinner wall and is typically more oval in shape than the aorta.

Once the aorta is visualized, the clinician should slide the probe caudally while keeping the aorta in the center of the screen. The celiac trunk will be initially visualized as the probe is moved, and the superior mesenteric artery will be superior caudal to the celiac trunk. The clinician should then continue to move the probe down caudally until the bifurcation, which is typically found just above the level of the umbilicus, is visualized. It is especially important to visualize the distal (infrarenal) aorta just above the bifurcation since this is where most AAAs occur.

A normal aorta caliber will measure less than 3 cm in diameter, and the common iliac vessels should measure half of that diameter (1.5 cm in adult women, 1.85 cm in adult men). Since the entire diameter of aorta that predicts the risk of rupture, it is critical that measurements include any thrombus present (Figure 2).

Once the entire aorta and bifurcation is seen in cross-section, the probe should be rotated clockwise 90 degrees so that the indicator marker is pointed toward the patient’s head; this will allow a longitudinal view of the aorta (Figure 3). When scanning longitudinally, it is important to place the probe over the center of the aorta as any lateral movement will cause the aorta to appear smaller than its actual size.

Points and Tips to Remember

To ensure the scan is performed correctly, it is essential to begin at the xiphoid process and then proceed caudally—without lifting the transducer off the patient. This will ensure the entire aorta is visualized, which is necessary to rule out an AAA.

During evaluation, bowel gas can obscure the image. If this occurs, the clinician should first try increasing the transducer pressure gradually or moving the probe back and forth while applying pressure in an attempt to displace the bowel gas. If this technique is unsuccessful, scanning off the midline or angling the probe may capture the aorta. Alternatively, a coronal image can be obtained by placing the probe on the patient’s right side in the midaxillary line with the indicator marker pointing toward the head.

Limitations

Despite the high sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting AAAs, there are some limitations to its use. Since the majority of AAAs rupture into the retroperitoneum, a rupture or leak is difficult to visualize on ultrasound. The EP should therefore recognize that the presence of an aneurysm alone in the setting of a convincing clinical history is sufficient to make the diagnosis.

Conclusion

Prompt evaluation and management of patients presenting with a suspected AAA are essential to avoid rupture, a catastrophic event with an extremely high-mortality rate. When the proper techniques for visualization are employed, including proper measurement of the aorta, bedside ultrasound is highly sensitive and specific for detecting an AAA.

Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.