User login

Case

An 84-year-old man, who was a resident at a local nursing home, presented for evaluation after the nursing staff noticed an increasingly swollen mass on the patient’s left groin. The patient’s medical history was significant for bilateral aortofemoral graft surgery, dementia, hypertension, and severe peripheral artery disease (PAD). He was not on any anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents. Due to the patient’s dementia, he was unable to provide a history regarding the onset of the swelling or any other signs or symptoms.

On examination, the patient did not appear in distress. His son, who was the patient’s durable power of attorney, was likewise unable to provide a clear timeframe regarding onset of the mass. The patient had no recent history of trauma and had not undergone any recent medical procedures. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 13 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

Clinical examination revealed a pulsatile, purple left groin mass and bruit. The mass was located around the left inguinal ligament and extended down the proximal, inner thigh (Figure 1). There was no drainage or lesions from the mass. Inspection of the patient’s hip demonstrated decreased adduction, limited by the mass; otherwise, there was normal range of motion. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were equal and intact, and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

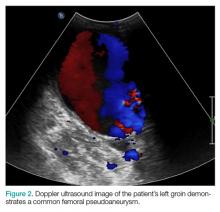

The patient tolerated the examination without focal signs of discomfort. A Doppler ultrasound revealed findings consistent with a common femoral pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (Figure 2). For better visualization and extension, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained, which demonstrated a PSA measuring 11.7 x 10.7 x 7.3 cm; there was no active extravasation (Figure 3).

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline while vascular surgery services was consulted for management and repair. After a discussion with the son regarding the patient’s wishes, surgical intervention was refused and the patient was conservatively managed and transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A true aneurysm differs from a PSA in that true aneurysms involve all three layers of the vessel wall. A PSA consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of encapsulating fibrous tissue or surrounding tissue.

Etiology

Femoral artery PSAs can be iatrogenic, for example, develop following cardiac catheterization or at the anastomotic site of previous surgery.1 The incidence of diagnostic postcatheterization PSA ranges from 0.05% to 2%, whereas interventional postcatheterization PSA ranges from 2% to 6%.2

With the increasing number of peripheral coronary diagnostics and interventions, emergency physicians should include PSA in the differential diagnosis of patients with a recent or remote history of catheterization or bypass grafts. Less commonly, femoral PSAs are caused by non-surgical trauma or infection (ie, mycotic PSA). Patient risk factors for development of PSA include obesity, hypertension, PAD, and anticoagulation.3 Patients with femoral artery PSAs may present with a painful or painless pulsatile mass. Mass effect of the PSA can compress nearby neurovascular structures, leading to femoral neuropathies or limb edema secondary to venous obstruction.4 Complications of embolization or thrombosis can cause limb ischemia, neuropathy, and claudication, while rupture may present with a rapidly expanding groin hematoma. Additionally, sizeable PSAs can cause overlying skin necrosis.5

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of a PSA can be made through Doppler ultrasound, which is the preferred imaging modality due to its accuracy, noninvasive nature, and low cost. Doppler ultrasound has been found to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 97% in detecting PSAs. Additional imaging with CTA can provide further definition of vasculopathy.6 Treatment should be considered for patients with a symptomatic femoral PSA, a PSA measuring more than 3 cm, or patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Studies have shown that observation-only and follow-up may be appropriate for patients with a PSA measuring less than 3 cm. A study by Toursarkissian et al7 found that the majority of PSAs smaller than 3 cm spontaneously resolved in a mean of 23 days without limb-threatening complications.

Treatment

Traditionally, open surgical repair techniques were the only treatment option for PSAs. However, in the early 1990s, the advent of new techniques such as stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, have developed as alternatives to open surgical repair; there has been variable success to these minimally invasive approaches.5,8

Ultrasound-Guided Compression. A conservative approach to treating PSAs, ultrasound-guided compression requires sustained compression by a skilled physician. This technique is associated with significant discomfort to the patient.5 Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. This technique is the treatment of choice for postcatheterization PSA. However, this intervention is contraindicated in patients who have concerning features such as an infected PSA, rapid expansion, skin necrosis, or signs of limb ischemia. Additionally, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is not appropriate for use in patients with a PSA occurring at anastomosis of a synthetic graft and native artery.5

Conclusion

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history of aortofemoral bypass surgery, we suspected a femoral PSA. While the PSA noted in our patient was sizeable, imaging studies and clinical examination showed no sign of limb ischemia or rupture.

Femoral PSAs are usually iatrogenic in nature, typically developing shortly after catheterization or a previous bypass surgery. The most serious complication of a PSA is rupture, but a thorough examination of the distal extremity is warranted to assess for limb ischemia as well. Ultrasound imaging is considered the modality of choice based on its high sensitivity and sensitivity for detecting PSAs.

Small PSAs (<3 cm) can be managed medically, but larger PSAs (>3 cm) require treatment. Newer techniques, including stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection are alternatives to open surgical repair of larger, uncomplicated PSAs. However, urgent open surgical repair is the only option when there is evidence of a ruptured PSA, ischemia, or skin necrosis.

1. Faggioli GL, Stella A, Gargiulo M, Tarantini S, D’Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Morphology of small aneurysms: definition and impact on risk of rupture. Am J Surg. 1994;168(2):131-135.

2. Hessel SJ, Adams DF, Abrams HL. Complications of angiography. Radiology. 1981;138(2):273-281. doi:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455105.

3. Petrou E, Malakos I, Kampanarou S, Doulas N, Voudris V. Life-threatening rupture of a femoral pseudoaneurysm after cardiac catheterization. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2016;10:201-204. doi:10.2174/1874192401610010201.

4. Mees B, Robinson D, Verhagen H, Chuen J. Non-aortic aneurysms—natural history and recommendations for referral and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):370-374.

5. Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973.

6. Coughlin BF, Paushter DM. Peripheral pseudoaneurysms: evaluation with duplex US. Radiology. 1988;168(2):339-342. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3293107.

7. Toursarkissian B, Allen BT, Petrinec D, et al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):803-809; discussion 808-809.

8. Corriere MA, Guzman RJ. True and false aneurysms of the femoral artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(4):216-223. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.09.008.

Case

An 84-year-old man, who was a resident at a local nursing home, presented for evaluation after the nursing staff noticed an increasingly swollen mass on the patient’s left groin. The patient’s medical history was significant for bilateral aortofemoral graft surgery, dementia, hypertension, and severe peripheral artery disease (PAD). He was not on any anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents. Due to the patient’s dementia, he was unable to provide a history regarding the onset of the swelling or any other signs or symptoms.

On examination, the patient did not appear in distress. His son, who was the patient’s durable power of attorney, was likewise unable to provide a clear timeframe regarding onset of the mass. The patient had no recent history of trauma and had not undergone any recent medical procedures. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 13 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

Clinical examination revealed a pulsatile, purple left groin mass and bruit. The mass was located around the left inguinal ligament and extended down the proximal, inner thigh (Figure 1). There was no drainage or lesions from the mass. Inspection of the patient’s hip demonstrated decreased adduction, limited by the mass; otherwise, there was normal range of motion. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were equal and intact, and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

The patient tolerated the examination without focal signs of discomfort. A Doppler ultrasound revealed findings consistent with a common femoral pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (Figure 2). For better visualization and extension, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained, which demonstrated a PSA measuring 11.7 x 10.7 x 7.3 cm; there was no active extravasation (Figure 3).

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline while vascular surgery services was consulted for management and repair. After a discussion with the son regarding the patient’s wishes, surgical intervention was refused and the patient was conservatively managed and transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A true aneurysm differs from a PSA in that true aneurysms involve all three layers of the vessel wall. A PSA consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of encapsulating fibrous tissue or surrounding tissue.

Etiology

Femoral artery PSAs can be iatrogenic, for example, develop following cardiac catheterization or at the anastomotic site of previous surgery.1 The incidence of diagnostic postcatheterization PSA ranges from 0.05% to 2%, whereas interventional postcatheterization PSA ranges from 2% to 6%.2

With the increasing number of peripheral coronary diagnostics and interventions, emergency physicians should include PSA in the differential diagnosis of patients with a recent or remote history of catheterization or bypass grafts. Less commonly, femoral PSAs are caused by non-surgical trauma or infection (ie, mycotic PSA). Patient risk factors for development of PSA include obesity, hypertension, PAD, and anticoagulation.3 Patients with femoral artery PSAs may present with a painful or painless pulsatile mass. Mass effect of the PSA can compress nearby neurovascular structures, leading to femoral neuropathies or limb edema secondary to venous obstruction.4 Complications of embolization or thrombosis can cause limb ischemia, neuropathy, and claudication, while rupture may present with a rapidly expanding groin hematoma. Additionally, sizeable PSAs can cause overlying skin necrosis.5

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of a PSA can be made through Doppler ultrasound, which is the preferred imaging modality due to its accuracy, noninvasive nature, and low cost. Doppler ultrasound has been found to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 97% in detecting PSAs. Additional imaging with CTA can provide further definition of vasculopathy.6 Treatment should be considered for patients with a symptomatic femoral PSA, a PSA measuring more than 3 cm, or patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Studies have shown that observation-only and follow-up may be appropriate for patients with a PSA measuring less than 3 cm. A study by Toursarkissian et al7 found that the majority of PSAs smaller than 3 cm spontaneously resolved in a mean of 23 days without limb-threatening complications.

Treatment

Traditionally, open surgical repair techniques were the only treatment option for PSAs. However, in the early 1990s, the advent of new techniques such as stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, have developed as alternatives to open surgical repair; there has been variable success to these minimally invasive approaches.5,8

Ultrasound-Guided Compression. A conservative approach to treating PSAs, ultrasound-guided compression requires sustained compression by a skilled physician. This technique is associated with significant discomfort to the patient.5 Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. This technique is the treatment of choice for postcatheterization PSA. However, this intervention is contraindicated in patients who have concerning features such as an infected PSA, rapid expansion, skin necrosis, or signs of limb ischemia. Additionally, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is not appropriate for use in patients with a PSA occurring at anastomosis of a synthetic graft and native artery.5

Conclusion

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history of aortofemoral bypass surgery, we suspected a femoral PSA. While the PSA noted in our patient was sizeable, imaging studies and clinical examination showed no sign of limb ischemia or rupture.

Femoral PSAs are usually iatrogenic in nature, typically developing shortly after catheterization or a previous bypass surgery. The most serious complication of a PSA is rupture, but a thorough examination of the distal extremity is warranted to assess for limb ischemia as well. Ultrasound imaging is considered the modality of choice based on its high sensitivity and sensitivity for detecting PSAs.

Small PSAs (<3 cm) can be managed medically, but larger PSAs (>3 cm) require treatment. Newer techniques, including stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection are alternatives to open surgical repair of larger, uncomplicated PSAs. However, urgent open surgical repair is the only option when there is evidence of a ruptured PSA, ischemia, or skin necrosis.

Case

An 84-year-old man, who was a resident at a local nursing home, presented for evaluation after the nursing staff noticed an increasingly swollen mass on the patient’s left groin. The patient’s medical history was significant for bilateral aortofemoral graft surgery, dementia, hypertension, and severe peripheral artery disease (PAD). He was not on any anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents. Due to the patient’s dementia, he was unable to provide a history regarding the onset of the swelling or any other signs or symptoms.

On examination, the patient did not appear in distress. His son, who was the patient’s durable power of attorney, was likewise unable to provide a clear timeframe regarding onset of the mass. The patient had no recent history of trauma and had not undergone any recent medical procedures. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 13 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

Clinical examination revealed a pulsatile, purple left groin mass and bruit. The mass was located around the left inguinal ligament and extended down the proximal, inner thigh (Figure 1). There was no drainage or lesions from the mass. Inspection of the patient’s hip demonstrated decreased adduction, limited by the mass; otherwise, there was normal range of motion. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were equal and intact, and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

The patient tolerated the examination without focal signs of discomfort. A Doppler ultrasound revealed findings consistent with a common femoral pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (Figure 2). For better visualization and extension, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained, which demonstrated a PSA measuring 11.7 x 10.7 x 7.3 cm; there was no active extravasation (Figure 3).

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline while vascular surgery services was consulted for management and repair. After a discussion with the son regarding the patient’s wishes, surgical intervention was refused and the patient was conservatively managed and transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A true aneurysm differs from a PSA in that true aneurysms involve all three layers of the vessel wall. A PSA consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of encapsulating fibrous tissue or surrounding tissue.

Etiology

Femoral artery PSAs can be iatrogenic, for example, develop following cardiac catheterization or at the anastomotic site of previous surgery.1 The incidence of diagnostic postcatheterization PSA ranges from 0.05% to 2%, whereas interventional postcatheterization PSA ranges from 2% to 6%.2

With the increasing number of peripheral coronary diagnostics and interventions, emergency physicians should include PSA in the differential diagnosis of patients with a recent or remote history of catheterization or bypass grafts. Less commonly, femoral PSAs are caused by non-surgical trauma or infection (ie, mycotic PSA). Patient risk factors for development of PSA include obesity, hypertension, PAD, and anticoagulation.3 Patients with femoral artery PSAs may present with a painful or painless pulsatile mass. Mass effect of the PSA can compress nearby neurovascular structures, leading to femoral neuropathies or limb edema secondary to venous obstruction.4 Complications of embolization or thrombosis can cause limb ischemia, neuropathy, and claudication, while rupture may present with a rapidly expanding groin hematoma. Additionally, sizeable PSAs can cause overlying skin necrosis.5

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of a PSA can be made through Doppler ultrasound, which is the preferred imaging modality due to its accuracy, noninvasive nature, and low cost. Doppler ultrasound has been found to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 97% in detecting PSAs. Additional imaging with CTA can provide further definition of vasculopathy.6 Treatment should be considered for patients with a symptomatic femoral PSA, a PSA measuring more than 3 cm, or patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Studies have shown that observation-only and follow-up may be appropriate for patients with a PSA measuring less than 3 cm. A study by Toursarkissian et al7 found that the majority of PSAs smaller than 3 cm spontaneously resolved in a mean of 23 days without limb-threatening complications.

Treatment

Traditionally, open surgical repair techniques were the only treatment option for PSAs. However, in the early 1990s, the advent of new techniques such as stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, have developed as alternatives to open surgical repair; there has been variable success to these minimally invasive approaches.5,8

Ultrasound-Guided Compression. A conservative approach to treating PSAs, ultrasound-guided compression requires sustained compression by a skilled physician. This technique is associated with significant discomfort to the patient.5 Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. This technique is the treatment of choice for postcatheterization PSA. However, this intervention is contraindicated in patients who have concerning features such as an infected PSA, rapid expansion, skin necrosis, or signs of limb ischemia. Additionally, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is not appropriate for use in patients with a PSA occurring at anastomosis of a synthetic graft and native artery.5

Conclusion

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history of aortofemoral bypass surgery, we suspected a femoral PSA. While the PSA noted in our patient was sizeable, imaging studies and clinical examination showed no sign of limb ischemia or rupture.

Femoral PSAs are usually iatrogenic in nature, typically developing shortly after catheterization or a previous bypass surgery. The most serious complication of a PSA is rupture, but a thorough examination of the distal extremity is warranted to assess for limb ischemia as well. Ultrasound imaging is considered the modality of choice based on its high sensitivity and sensitivity for detecting PSAs.

Small PSAs (<3 cm) can be managed medically, but larger PSAs (>3 cm) require treatment. Newer techniques, including stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection are alternatives to open surgical repair of larger, uncomplicated PSAs. However, urgent open surgical repair is the only option when there is evidence of a ruptured PSA, ischemia, or skin necrosis.

1. Faggioli GL, Stella A, Gargiulo M, Tarantini S, D’Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Morphology of small aneurysms: definition and impact on risk of rupture. Am J Surg. 1994;168(2):131-135.

2. Hessel SJ, Adams DF, Abrams HL. Complications of angiography. Radiology. 1981;138(2):273-281. doi:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455105.

3. Petrou E, Malakos I, Kampanarou S, Doulas N, Voudris V. Life-threatening rupture of a femoral pseudoaneurysm after cardiac catheterization. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2016;10:201-204. doi:10.2174/1874192401610010201.

4. Mees B, Robinson D, Verhagen H, Chuen J. Non-aortic aneurysms—natural history and recommendations for referral and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):370-374.

5. Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973.

6. Coughlin BF, Paushter DM. Peripheral pseudoaneurysms: evaluation with duplex US. Radiology. 1988;168(2):339-342. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3293107.

7. Toursarkissian B, Allen BT, Petrinec D, et al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):803-809; discussion 808-809.

8. Corriere MA, Guzman RJ. True and false aneurysms of the femoral artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(4):216-223. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.09.008.

1. Faggioli GL, Stella A, Gargiulo M, Tarantini S, D’Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Morphology of small aneurysms: definition and impact on risk of rupture. Am J Surg. 1994;168(2):131-135.

2. Hessel SJ, Adams DF, Abrams HL. Complications of angiography. Radiology. 1981;138(2):273-281. doi:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455105.

3. Petrou E, Malakos I, Kampanarou S, Doulas N, Voudris V. Life-threatening rupture of a femoral pseudoaneurysm after cardiac catheterization. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2016;10:201-204. doi:10.2174/1874192401610010201.

4. Mees B, Robinson D, Verhagen H, Chuen J. Non-aortic aneurysms—natural history and recommendations for referral and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):370-374.

5. Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973.

6. Coughlin BF, Paushter DM. Peripheral pseudoaneurysms: evaluation with duplex US. Radiology. 1988;168(2):339-342. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3293107.

7. Toursarkissian B, Allen BT, Petrinec D, et al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):803-809; discussion 808-809.

8. Corriere MA, Guzman RJ. True and false aneurysms of the femoral artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(4):216-223. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.09.008.