User login

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

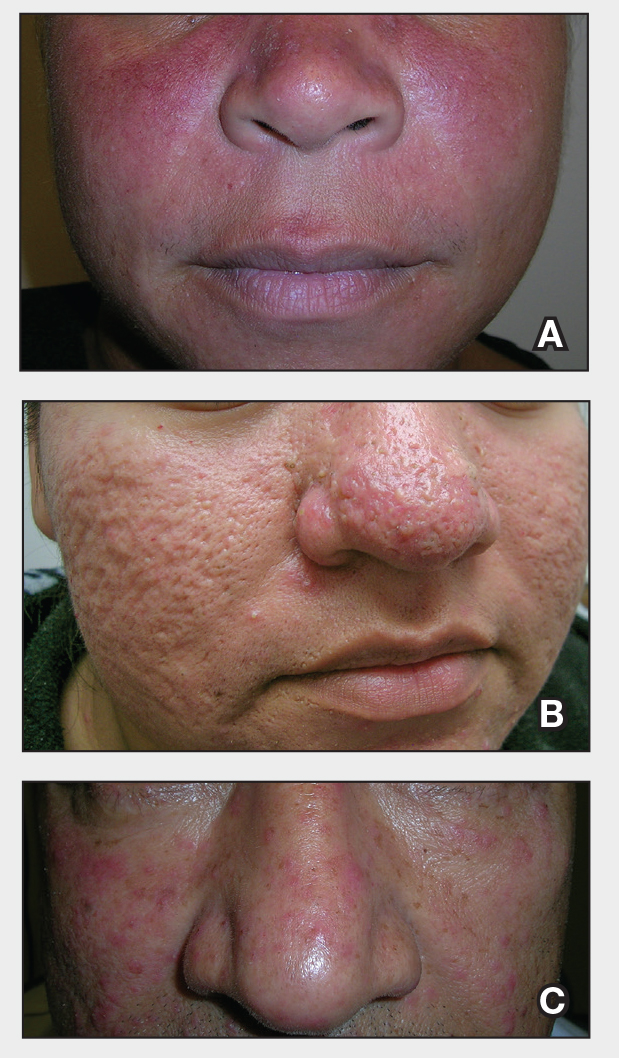

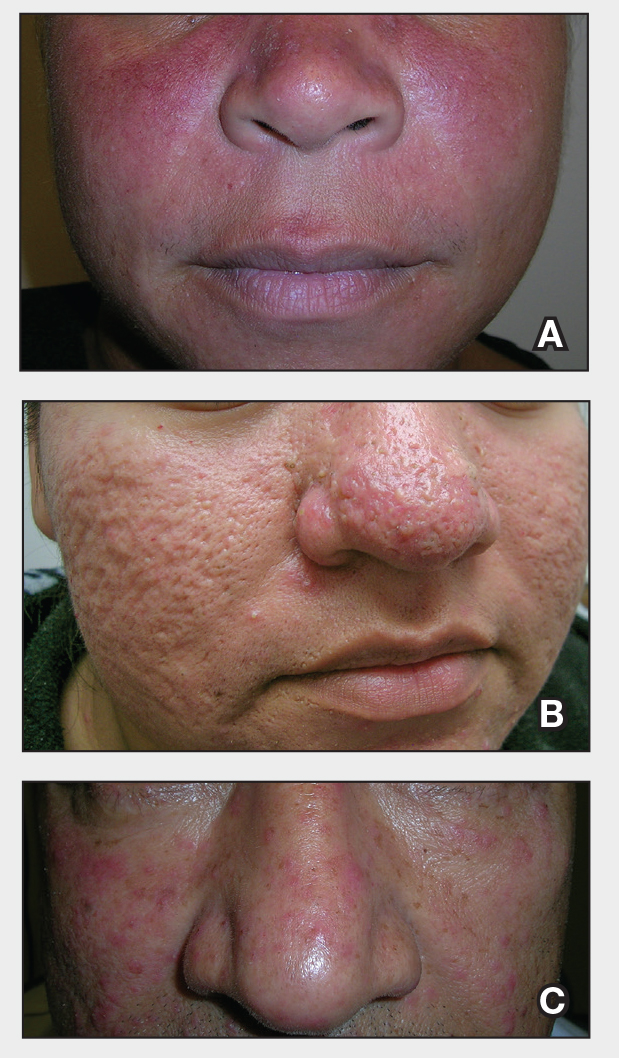

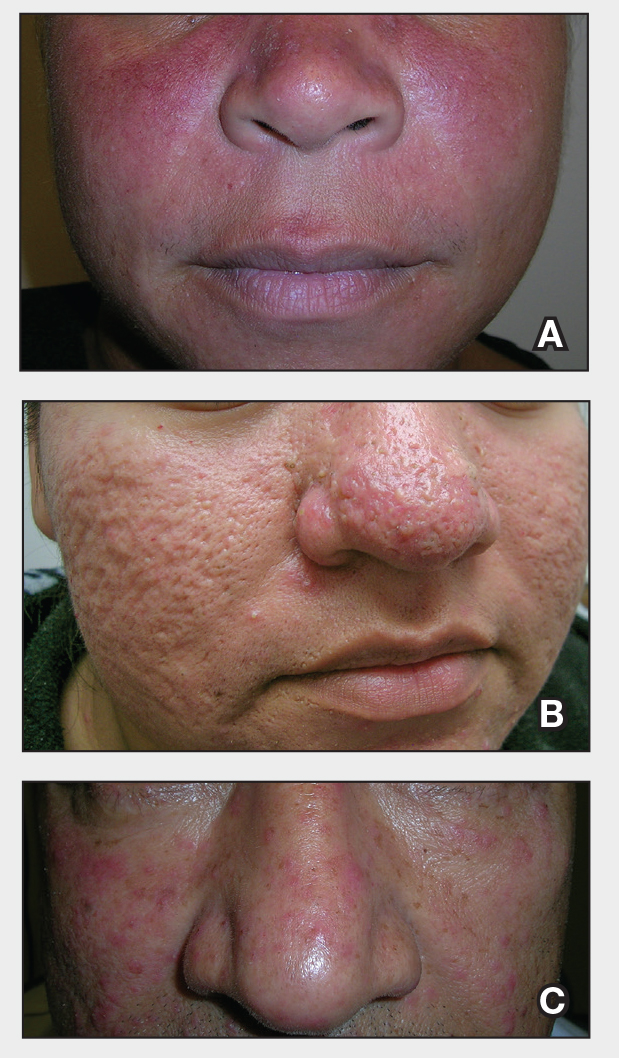

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types