User login

CASE Lauren C, age 35, presents with fatigue, which she says started at least eight months ago and has progressively worsened. The patient, a clerical worker, says she manages to do an adequate job but goes home feeling utterly exhausted each night.

Lauren says she sleeps well, getting more than eight hours of sleep per night on weekends but less than seven hours per night during the week. But no matter how long she sleeps, she never awakens feeling refreshed. Lauren reports that she doesn’t smoke, has no more than four alcoholic drinks per month, and adheres to an “average” diet. She is too tired to exercise.

Lauren is single, with no children. Although she says she has a strong network of family and friends, she increasingly finds she has no energy for socializing. If Lauren were your patient, what would you do?

Fatigue is a common presenting symptom in primary care, accounting for about 5% of adult visits.1 Defined as a generalized lack of energy, fatigue that persists despite adequate rest or is severe enough to disrupt an individual’s ability to participate in key social and/or occupational activities warrants a thorough investigation.

Because fatigue is a nonspecific symptom that may be linked to a number of medical and psychiatric illnesses or to medications used to treat them, determining the cause can be difficult. In about half of all cases, no specific etiology is found.2This review, which includes the elements of a work-up and management strategies for patients presenting with ongoing fatigue, will help you arrive at the appropriate diagnosis and provide optimal treatment.

CHRONIC FATIGUE: DEFINING THE TERMS

A definition of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) was initially published in 1988.3In subsequent years, the term myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) became popular. Although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, ME often refers to patients whose condition is thought to have an infectious cause and for whom postexertional malaise is a hallmark symptom.4

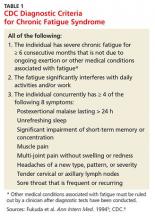

CDC criteria. While several sets of diagnostic criteria for CFS have been developed, the most widely used is that of the CDC, published in 1994 (see Table 1).5,6A diagnosis of CFS is made on the basis of exclusion, subjective clinical interpretation, and patient self-report.

When the first two criteria—fatigue not due to ongoing exertion or other medical conditions that has lasted ≥ 6 months and is severe enough to interfere with daily activities—but fewer than four of the CDC’s eight concurrent symptoms (eg, headache, unrefreshing sleep, and postexertion malaise lasting > 24 h) are present, idiopathic fatigue, rather than CFS, is diagnosed.6

International Consensus Criteria (ICC). In 2011, the ICC for ME were proposed in an effort to provide more specific diagnostic criteria (see Table 2).7The ICC emphasize fatigability, or what the authors identify as “post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion.”

The ICC have not yet been broadly researched. But an Australian study of patients with chronic fatigue found that those who met the ICC definition were sicker and more homogeneous, with significantly lower scores for physical and social functioning and bodily pain, compared with those who fulfilled the CDC criteria alone.8

Continue for common threads of chronic fatigue & neuropsychiatric conditions >>

CHRONIC FATIGUE & NEUROPSYCHIATRIC CONDITIONS: COMMON THREADS

Recent research has made it clear that depression, somatization, and CFS share some biological underpinnings. These include biomarkers for inflammation, cell-mediated immune activation—which may be related to the symptoms of fatigue—autonomic dysfunction, and hyperalgesia.9Evidence suggests that up to two-thirds of patients with CFS also meet the criteria for a psychiatric disorder.10The most common psychiatric conditions are major depressive disorder (MDD), affecting an estimated 22% to 32% of those with CFS; anxiety disorder, affecting about 20%; and somatization disorder, affecting about 10%—at least double the incidence of the general population.10

Others point out, however, that up to half of those with CFS do not have a psychiatric disorder.11A diagnosis of somatization disorder, in particular, depends largely on a subjective interpretation of whether the presenting symptoms have a physical cause.10

CFS and MDD comorbidity. The most widely studied association between CFS and psychiatric disorders involves MDD. Observational studies have found patients with CFS have a lifetime prevalence of MDD of 65%,12,13which is higher than that of patients with other chronic diseases. Overlapping symptoms include fatigue, sleep disturbance, poor concentration, and memory problems. However, those with CFS have fewer symptoms related to anhedonia, poor self-esteem, guilt, and suicidal ideation compared with individuals with MDD.12,13

There are several possible explanations for CFS and MDD comorbidity, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive.10One theory is that CFS is an atypical form of depression; another holds that the disability associated with CFS leads to depression, as is the case with many other chronic illnesses; and a third points to overlapping pathophysiology.10

An emerging body of evidence suggests that CFS and MDD have some common oxidative and nitrosative biochemical pathways. Activated by infection, psychologic stress, and immune disorders, they are believed to have damaging free radical and nitric oxide effects at the cellular level.14The cellular effects can result in fatigue, muscle pain, and flulike malaise.

Cortisol response differs

CFS and MDD might be distinguishable by another pathway—the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. MDD is classically associated with activation and raised cortisol levels, while CFS is consistently associated with impaired HPA axis functioning and reduced cortisol levels.10The majority of patients with CFS report symptoms of cognitive decline, with the acquisition of new verbal learning and information-processing speed particularly likely to be impaired.15

A meta-analysis of 50 studies of patients with CFS showed deficits in attention, memory, and reaction time, but not in fine motor speed, vocabulary, or reasoning.16Autonomic dysfunction has also been observed, including disordered sympathetic activity. The most frequently observed abnormalities on autonomic testing are postural hypotension, tachycardia syndrome, neurally mediated hypotension, and heart rate variability during tilt table testing.16

THE LINK BETWEEN INFECTION AND CFS

Several infectious agents have been associated with ME/CFS, including the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex virus 6, parvovirus, Q fever, and Lyme disease.8,17,18 Most agents that have been linked to ME/CFS are associated with persistent infection and thus incitement of the immune system.

Numerous observational studies17,18have documented postinfectious fatigue syndromes after acute viral and bacterial infections and symptoms suggestive of infection, such as fever, myalgias, and respiratory and gastrointestinal distress. In one prospective Australian study,19investigators identified 253 cases of acute EBV, Ross River virus, and Q fever. Of those 253 patients, 12% went on to develop CFS, with a higher likelihood among those with more severe acute symptoms. No correlation with preexisting psychiatric disorders was found.

Muscle mitochondria studies have demonstrated what appear to be acquired abnormalities in those with CFS.20,21Signs of increased oxidative stress have been found in both blood and muscle samples from patients with CFS, and longitudinal studies suggest that oxidative stress is greatest during periods of clinical exacerbation.22Increased lactate levels suggest increased anaerobic metabolism in the central nervous system consistent with mitochondrial dysfunction. Several studies have demonstrated that exercise can precipitate oxidative stress in patients with CFS, in contrast with healthy controls and controls with other chronic illnesses, suggesting a physiologic basis for their postexertional symptoms.17

Autoinflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants, a rare syndrome associated with vaccine administration, has been linked to postvaccination adverse events, exposure to silicone implants, Gulf War syndrome (related to multiple vaccinations), and macrophagic myofasciitis. All involve exposure to immune adjuvants and have similar clinical manifestations. The corresponding exposures appear to trigger an autoimmune response in susceptible individuals. The hepatitis B vaccine is most often associated with CFS, with symptoms occurring within 90 days of administration.23

Continue for the clinical work-up >>

THE CLINICAL WORK-UP: PUTTING KNOWLEDGE INTO PRACTICE

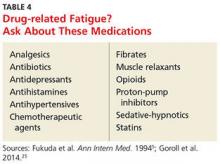

Familiarity with potential causes of and connections with ME/CFS will help you ensure that patients who say they’re always tired receive a thorough work-up. Start with a medical history, inquiring directly about medical and psychiatric disorders that may contribute to fatigue (see Table 3).5,24,25 Include a medication history as well, to help determine whether the fatigue is drug-related (see Table 4).5,25

What to ask. Determine the onset, course, duration, daily pattern, and impact of fatigue on the patient’s daily life. Inquire, too, about related symptoms of daytime sleepiness, dyspnea on exertion, generalized weakness, and depressed mood. The prominence of any of these rather than fatigue, per se, point to a diagnosis of a chronic illness other than ME/CFS.

Keep in mind, too, that patients with an organ-based medical illness tend to associate their fatigue with activities that they are unable to complete, such as shopping or light housework. In contrast, those with fatigue that is not organ-based typically say that they’re tired all the time. Their fatigue is not necessarily related to exertion, nor does it improve with rest.26

To address this distinction, take a sleep history, assessing both the quality and quantity of the patient’s sleep to determine how it affects symptoms.27 Consider using a questionnaire designed to help distinguish between sleepiness—and a primary sleep disorder—and fatigue,28 such as the Fatigue Severity Scale of Sleep Disorders (www.healthywomen.org/sites/default/files/FatigueSeverityScale.pdf).

What to rule out. In addition to a medical history, the physical examination should be oriented toward ruling out secondary causes of fatigue. In addition to a system-by-system approach to the differential diagnosis, carefully observe the patient’s general appearance, with attention to his or her level of alertness, grooming, and psychomotor agitation or retardation as possible signs of a psychiatric disorder. To rule out neurologic causes, evaluate muscle bulk, tone, and strength; deep tendon reflexes; and sensory and cranial nerves, as well.29

Lab tests to consider. In most cases of ME/CFS, basic studies—complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, blood chemistry, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels—are sufficient. When no medical or psychiatric cause has been found, additional tests may be ordered on a case-by-case basis, although laboratory analysis affects the management of fatigue in less than 5% of such patients.30 Tests to consider include:

• Creatine kinase (for patients who report pain or muscle weakness)

• Pregnancy test (for women of childbearing age)

• Ferritin testing (for young women who might benefit from iron supplementation for levels < 50 ng/mL even if anemia is not present)31

• Hepatitis C screening (recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force for those born between 1945 and 1965)32

• HIV screening and the purified protein derivative test for tuberculosis (based on patient history).

Forego routine testing for other infections

Routine testing for infectious diseases and conditions associated with fatigue, such as EBV or Lyme disease, immune deficiency (eg, immunoglobulins), inflammatory disease (eg, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor), celiac disease, vitamin D deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, or heavy metal toxicity, is unlikely to be helpful.29 Additional testing simply to reassure a worried patient usually does not accomplish that objective.33

Additional studies, referrals to consider. If you suspect that a patient has a sleep disorder, a referral to a sleep clinic to rule out idiopathic sleep disorders, obstructive sleep apnea, or movement disorders that interfere with sleep may be in order. Spirometry and echocardiography may be helpful for some patients. If you suspect peripheral muscle fatigue, a referral for neuromuscular testing is indicated.

Lauren’s medical history reveals that she also has irritable bowel syndrome, which she manages with diet and OTC medication, as needed for constipation or diarrhea. She denies having any other chronic conditions. Her only other symptoms, she reports, are mild upper back pain after spending long hours at the computer and arthralgias in her left knee and both hands. She admits to being “somewhat depressed” in the last few months but denies the presence of anhedonia.

The patient’s physical examination is normal, and her depression screen does not meet the criteria for MDD. Her metabolic chemistry panel, complete blood count, TSH, and sedimentation rate are all normal, as well.

Continue for symptom management and coping strategies >>

SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT AND COPING STRATEGIES

When no specific cause of chronic fatigue is found, the focus shifts from diagnosis to symptom management and coping strategies. This requires engagement with the patient. It is important to acknowledge the existence of his or her symptoms and to reassure the patient that further investigation may be warranted later, should new symptoms emerge. Advise the patient, too, that periods of remission and relapse are likely.

Strategies designed to motivate patient self-management, as well as the formulation of patient-centered treatment plans, have been shown to reduce symptom scores.34 Participation in a support group, as well as frequent follow-up visits with a primary care provider, a behavioral therapist, or both, may help to provide needed psychologic support.

Evidence of the effectiveness of specific therapies for ME/CFS is limited; however, the best-studied approaches are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy.35 Exercise should be low intensity, such as walking or cycling for 30 minutes three times a week, with a gradual increase in duration and frequency over a period of weeks to months. Patients with cancer-related fatigue may benefit from yoga, group therapy, and stress management.36

Associated mood and pain symptoms should be treated, as well. Bupropion, which is somewhat stimulating, may be considered as an initial treatment for patients with depression and clinically significant fatigue.

Other potentially beneficial approaches include a healthy diet, avoidance of more than nominal amounts of alcohol, relative avoidance of caffeine (no more than one cup of a caffeinated beverage in the morning), and stress reduction techniques.

Attention to good sleep hygiene may be especially beneficial, including a regular bedtime routine and sleep schedule, and elimination of bedroom light and noise. Pharmacologic treatments for insomnia should be used with caution, if at all.

Lauren receives a referral for CBT and is scheduled for a return visit in four weeks. At the advice of both her primary care provider and the behavioral therapist, she gradually makes several lifestyle changes. She begins going to bed earlier on weeknights to ensure that she sleeps for at least seven hours. She improves her diet, with increasing emphasis on vegetables, fruits, and whole grains. She also starts a walking program, increasing gradually to a total of three hours per week. After four months, she adds a weekly trip to a gym, where she practices resistance training for about 40 minutes.

Lauren also increases her social activities on weekends and recently accepted an invitation to join a book club. Six months from her initial visit, she notes that although she is still more easily fatigued than most people, she has made significant improvement

REFERENCES

1. Nijrolder I, van der Windt DA, van der Horst HE. Prognosis of fatigue and functioning in primary care: a 1-year follow-up study. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:519-527.

2. Griffith JP, Zarrouf FA. A systematic review of chronic fatigue syndrome: don’t assume it’s depression. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10:120-128.

3. Holmes GP, Kaplan JE, Gantz NM, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a working case definition. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:387-389.

4. Morris G, Maes M. Case definitions and diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome: from clinical consensus to evidence-based case definitions. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34:185-199.

5. Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:953-959.

6. CDC. Chronic fatigue syndrome. www.cdc.gov/cfs/diagnosis/index.html. Accessed December 17, 2015.

7. Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J Intern Med. 2011;270:327-338.

8. Johnston SC, Brenu EW, Hardcastle S, et al. A comparison of health status in patients meeting alternative definitions for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:64.

9. Anderson VR, Jason LA, Hlavaty LE, et al. A review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:147-155.

10. Christley Y, Duffy T, Everall IP, et al. The neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological features of chronic fatigue syndrome: revisiting the enigma. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:353.

11. Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel HH. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528-533.

12. Nater UM, Jones JF, Lin JM, et al. Personality features and personality disorders in chronic fatigue syndrome: a population-based study. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:312-318.

13. Taylor RR, Jason LA, Jahn SC. Chronic fatigue and sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of psychiatric disorders in a community-based sample. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:896-901.

14. Leonard B, Maes M. Mechanistic explanations of how cell-mediated immune activation, inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways and their sequels and concomitants play a role in the pathophysiology of unipolar depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:764-785.

15. DeLuca J, Christodoulou C, Diamond BJ, et al. Working memory deficits in chronic fatigue syndrome: differentiating between speed and accuracy of information processing. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:101-109.

16. Cockshell SJ, Mathias JL. Cognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1253-1267.

17. Komaroff AL, Cho TA. Role of infection and neurologic dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. Semin Neurol. 2011;31:325-337.

18. Naess H, Sundal E, Myhr KM, et al. Postinfectious and chronic fatigue syndromes: clinical experience from a tertiary-referral centre in Norway. In Vivo. 2010;24:185-188.

19. Hickie I, Davenport T, Wakefield D, et al; Dubbo Infection Outcomes Study Group. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2006;333:575.

20. Plioplys AV, Plioplys S. Electron-microscopic investigation of muscle mitochondria in chronic fatigue syndrome.Neuropsychobiology. 1995;32: 175-181.

21. Vernon SD, Whistler T, Cameron B, et al. Preliminary evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction associated with post-infective fatigue after acute infection with Epstein Barr virus. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:15.

22. Miwa K, Fujita M. Fluctuation of serum vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) concentrations during exacerbation and remission phases in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Heart Vessels. 2010;25:319-323.

23. Rosenblum H, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. The common immunogenic etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome: from infections to vaccines via adjuvants to the ASIA syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2011;25:851-863.

24. Vincent A, Brimmer DJ, Whipple MO, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and classification of chronic fatigue syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota as estimated using the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1145-1152.

25. Goroll AH, Mulley AG. Primary Care Medicine: Office Evaluation and Management of the Adult Patient. 7th ed. Morrisville, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

26. Brown RF, Schutte NS. Direct and indirect relationships between emotional intelligence and subjective fatigue in university students. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:585-593.

27. Pigeon WR, Sateia MJ, Ferguson RJ. Distinguishing between excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue: toward improved detection and treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:61-69.

28. Bailes S, Libman E, Baltzan M, et al. Brief and distinct empirical sleepiness and fatigue scales. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:605-613.

29. National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (UK). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy): Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy) in Adults and Children. London, UK: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2007.

30. Lane TJ, Matthews DA, Manu P. The low yield of physical examinations and laboratory investigations of patients with chronic fatigue. Am J Med Sci. 1990;299:313-318.

31. Vaucher P, Druisw PL, Waldvogel S, et al. Effect of iron supplementation on fatigue in nonanemic menstruating women with low ferritin: a randomized controlled trial.CMAJ. 2012;184:1247-1254.

32. US Preventive Services Task Force. Hepatitis C: Screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspshepc.htm. Accessed December 17, 2015.

33. Rolfe A, Burton C. Reassurance after diagnostic testing with a low pretest probability of serious disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:407-416.

34. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671-677.

35. White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, et al; PACE trial management group. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377:823-836.

36. van Weert E, Hoekstra-Weebers J, Otter R, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: predictors and effects of rehabilitation. Oncologist. 2006;11:184-196.

CASE Lauren C, age 35, presents with fatigue, which she says started at least eight months ago and has progressively worsened. The patient, a clerical worker, says she manages to do an adequate job but goes home feeling utterly exhausted each night.

Lauren says she sleeps well, getting more than eight hours of sleep per night on weekends but less than seven hours per night during the week. But no matter how long she sleeps, she never awakens feeling refreshed. Lauren reports that she doesn’t smoke, has no more than four alcoholic drinks per month, and adheres to an “average” diet. She is too tired to exercise.

Lauren is single, with no children. Although she says she has a strong network of family and friends, she increasingly finds she has no energy for socializing. If Lauren were your patient, what would you do?

Fatigue is a common presenting symptom in primary care, accounting for about 5% of adult visits.1 Defined as a generalized lack of energy, fatigue that persists despite adequate rest or is severe enough to disrupt an individual’s ability to participate in key social and/or occupational activities warrants a thorough investigation.

Because fatigue is a nonspecific symptom that may be linked to a number of medical and psychiatric illnesses or to medications used to treat them, determining the cause can be difficult. In about half of all cases, no specific etiology is found.2This review, which includes the elements of a work-up and management strategies for patients presenting with ongoing fatigue, will help you arrive at the appropriate diagnosis and provide optimal treatment.

CHRONIC FATIGUE: DEFINING THE TERMS

A definition of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) was initially published in 1988.3In subsequent years, the term myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) became popular. Although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, ME often refers to patients whose condition is thought to have an infectious cause and for whom postexertional malaise is a hallmark symptom.4

CDC criteria. While several sets of diagnostic criteria for CFS have been developed, the most widely used is that of the CDC, published in 1994 (see Table 1).5,6A diagnosis of CFS is made on the basis of exclusion, subjective clinical interpretation, and patient self-report.

When the first two criteria—fatigue not due to ongoing exertion or other medical conditions that has lasted ≥ 6 months and is severe enough to interfere with daily activities—but fewer than four of the CDC’s eight concurrent symptoms (eg, headache, unrefreshing sleep, and postexertion malaise lasting > 24 h) are present, idiopathic fatigue, rather than CFS, is diagnosed.6

International Consensus Criteria (ICC). In 2011, the ICC for ME were proposed in an effort to provide more specific diagnostic criteria (see Table 2).7The ICC emphasize fatigability, or what the authors identify as “post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion.”

The ICC have not yet been broadly researched. But an Australian study of patients with chronic fatigue found that those who met the ICC definition were sicker and more homogeneous, with significantly lower scores for physical and social functioning and bodily pain, compared with those who fulfilled the CDC criteria alone.8

Continue for common threads of chronic fatigue & neuropsychiatric conditions >>

CHRONIC FATIGUE & NEUROPSYCHIATRIC CONDITIONS: COMMON THREADS

Recent research has made it clear that depression, somatization, and CFS share some biological underpinnings. These include biomarkers for inflammation, cell-mediated immune activation—which may be related to the symptoms of fatigue—autonomic dysfunction, and hyperalgesia.9Evidence suggests that up to two-thirds of patients with CFS also meet the criteria for a psychiatric disorder.10The most common psychiatric conditions are major depressive disorder (MDD), affecting an estimated 22% to 32% of those with CFS; anxiety disorder, affecting about 20%; and somatization disorder, affecting about 10%—at least double the incidence of the general population.10

Others point out, however, that up to half of those with CFS do not have a psychiatric disorder.11A diagnosis of somatization disorder, in particular, depends largely on a subjective interpretation of whether the presenting symptoms have a physical cause.10

CFS and MDD comorbidity. The most widely studied association between CFS and psychiatric disorders involves MDD. Observational studies have found patients with CFS have a lifetime prevalence of MDD of 65%,12,13which is higher than that of patients with other chronic diseases. Overlapping symptoms include fatigue, sleep disturbance, poor concentration, and memory problems. However, those with CFS have fewer symptoms related to anhedonia, poor self-esteem, guilt, and suicidal ideation compared with individuals with MDD.12,13

There are several possible explanations for CFS and MDD comorbidity, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive.10One theory is that CFS is an atypical form of depression; another holds that the disability associated with CFS leads to depression, as is the case with many other chronic illnesses; and a third points to overlapping pathophysiology.10

An emerging body of evidence suggests that CFS and MDD have some common oxidative and nitrosative biochemical pathways. Activated by infection, psychologic stress, and immune disorders, they are believed to have damaging free radical and nitric oxide effects at the cellular level.14The cellular effects can result in fatigue, muscle pain, and flulike malaise.

Cortisol response differs

CFS and MDD might be distinguishable by another pathway—the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. MDD is classically associated with activation and raised cortisol levels, while CFS is consistently associated with impaired HPA axis functioning and reduced cortisol levels.10The majority of patients with CFS report symptoms of cognitive decline, with the acquisition of new verbal learning and information-processing speed particularly likely to be impaired.15

A meta-analysis of 50 studies of patients with CFS showed deficits in attention, memory, and reaction time, but not in fine motor speed, vocabulary, or reasoning.16Autonomic dysfunction has also been observed, including disordered sympathetic activity. The most frequently observed abnormalities on autonomic testing are postural hypotension, tachycardia syndrome, neurally mediated hypotension, and heart rate variability during tilt table testing.16

THE LINK BETWEEN INFECTION AND CFS

Several infectious agents have been associated with ME/CFS, including the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex virus 6, parvovirus, Q fever, and Lyme disease.8,17,18 Most agents that have been linked to ME/CFS are associated with persistent infection and thus incitement of the immune system.

Numerous observational studies17,18have documented postinfectious fatigue syndromes after acute viral and bacterial infections and symptoms suggestive of infection, such as fever, myalgias, and respiratory and gastrointestinal distress. In one prospective Australian study,19investigators identified 253 cases of acute EBV, Ross River virus, and Q fever. Of those 253 patients, 12% went on to develop CFS, with a higher likelihood among those with more severe acute symptoms. No correlation with preexisting psychiatric disorders was found.

Muscle mitochondria studies have demonstrated what appear to be acquired abnormalities in those with CFS.20,21Signs of increased oxidative stress have been found in both blood and muscle samples from patients with CFS, and longitudinal studies suggest that oxidative stress is greatest during periods of clinical exacerbation.22Increased lactate levels suggest increased anaerobic metabolism in the central nervous system consistent with mitochondrial dysfunction. Several studies have demonstrated that exercise can precipitate oxidative stress in patients with CFS, in contrast with healthy controls and controls with other chronic illnesses, suggesting a physiologic basis for their postexertional symptoms.17

Autoinflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants, a rare syndrome associated with vaccine administration, has been linked to postvaccination adverse events, exposure to silicone implants, Gulf War syndrome (related to multiple vaccinations), and macrophagic myofasciitis. All involve exposure to immune adjuvants and have similar clinical manifestations. The corresponding exposures appear to trigger an autoimmune response in susceptible individuals. The hepatitis B vaccine is most often associated with CFS, with symptoms occurring within 90 days of administration.23

Continue for the clinical work-up >>

THE CLINICAL WORK-UP: PUTTING KNOWLEDGE INTO PRACTICE

Familiarity with potential causes of and connections with ME/CFS will help you ensure that patients who say they’re always tired receive a thorough work-up. Start with a medical history, inquiring directly about medical and psychiatric disorders that may contribute to fatigue (see Table 3).5,24,25 Include a medication history as well, to help determine whether the fatigue is drug-related (see Table 4).5,25

What to ask. Determine the onset, course, duration, daily pattern, and impact of fatigue on the patient’s daily life. Inquire, too, about related symptoms of daytime sleepiness, dyspnea on exertion, generalized weakness, and depressed mood. The prominence of any of these rather than fatigue, per se, point to a diagnosis of a chronic illness other than ME/CFS.

Keep in mind, too, that patients with an organ-based medical illness tend to associate their fatigue with activities that they are unable to complete, such as shopping or light housework. In contrast, those with fatigue that is not organ-based typically say that they’re tired all the time. Their fatigue is not necessarily related to exertion, nor does it improve with rest.26

To address this distinction, take a sleep history, assessing both the quality and quantity of the patient’s sleep to determine how it affects symptoms.27 Consider using a questionnaire designed to help distinguish between sleepiness—and a primary sleep disorder—and fatigue,28 such as the Fatigue Severity Scale of Sleep Disorders (www.healthywomen.org/sites/default/files/FatigueSeverityScale.pdf).

What to rule out. In addition to a medical history, the physical examination should be oriented toward ruling out secondary causes of fatigue. In addition to a system-by-system approach to the differential diagnosis, carefully observe the patient’s general appearance, with attention to his or her level of alertness, grooming, and psychomotor agitation or retardation as possible signs of a psychiatric disorder. To rule out neurologic causes, evaluate muscle bulk, tone, and strength; deep tendon reflexes; and sensory and cranial nerves, as well.29

Lab tests to consider. In most cases of ME/CFS, basic studies—complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, blood chemistry, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels—are sufficient. When no medical or psychiatric cause has been found, additional tests may be ordered on a case-by-case basis, although laboratory analysis affects the management of fatigue in less than 5% of such patients.30 Tests to consider include:

• Creatine kinase (for patients who report pain or muscle weakness)

• Pregnancy test (for women of childbearing age)

• Ferritin testing (for young women who might benefit from iron supplementation for levels < 50 ng/mL even if anemia is not present)31

• Hepatitis C screening (recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force for those born between 1945 and 1965)32

• HIV screening and the purified protein derivative test for tuberculosis (based on patient history).

Forego routine testing for other infections

Routine testing for infectious diseases and conditions associated with fatigue, such as EBV or Lyme disease, immune deficiency (eg, immunoglobulins), inflammatory disease (eg, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor), celiac disease, vitamin D deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, or heavy metal toxicity, is unlikely to be helpful.29 Additional testing simply to reassure a worried patient usually does not accomplish that objective.33

Additional studies, referrals to consider. If you suspect that a patient has a sleep disorder, a referral to a sleep clinic to rule out idiopathic sleep disorders, obstructive sleep apnea, or movement disorders that interfere with sleep may be in order. Spirometry and echocardiography may be helpful for some patients. If you suspect peripheral muscle fatigue, a referral for neuromuscular testing is indicated.

Lauren’s medical history reveals that she also has irritable bowel syndrome, which she manages with diet and OTC medication, as needed for constipation or diarrhea. She denies having any other chronic conditions. Her only other symptoms, she reports, are mild upper back pain after spending long hours at the computer and arthralgias in her left knee and both hands. She admits to being “somewhat depressed” in the last few months but denies the presence of anhedonia.

The patient’s physical examination is normal, and her depression screen does not meet the criteria for MDD. Her metabolic chemistry panel, complete blood count, TSH, and sedimentation rate are all normal, as well.

Continue for symptom management and coping strategies >>

SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT AND COPING STRATEGIES

When no specific cause of chronic fatigue is found, the focus shifts from diagnosis to symptom management and coping strategies. This requires engagement with the patient. It is important to acknowledge the existence of his or her symptoms and to reassure the patient that further investigation may be warranted later, should new symptoms emerge. Advise the patient, too, that periods of remission and relapse are likely.

Strategies designed to motivate patient self-management, as well as the formulation of patient-centered treatment plans, have been shown to reduce symptom scores.34 Participation in a support group, as well as frequent follow-up visits with a primary care provider, a behavioral therapist, or both, may help to provide needed psychologic support.

Evidence of the effectiveness of specific therapies for ME/CFS is limited; however, the best-studied approaches are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy.35 Exercise should be low intensity, such as walking or cycling for 30 minutes three times a week, with a gradual increase in duration and frequency over a period of weeks to months. Patients with cancer-related fatigue may benefit from yoga, group therapy, and stress management.36

Associated mood and pain symptoms should be treated, as well. Bupropion, which is somewhat stimulating, may be considered as an initial treatment for patients with depression and clinically significant fatigue.

Other potentially beneficial approaches include a healthy diet, avoidance of more than nominal amounts of alcohol, relative avoidance of caffeine (no more than one cup of a caffeinated beverage in the morning), and stress reduction techniques.

Attention to good sleep hygiene may be especially beneficial, including a regular bedtime routine and sleep schedule, and elimination of bedroom light and noise. Pharmacologic treatments for insomnia should be used with caution, if at all.

Lauren receives a referral for CBT and is scheduled for a return visit in four weeks. At the advice of both her primary care provider and the behavioral therapist, she gradually makes several lifestyle changes. She begins going to bed earlier on weeknights to ensure that she sleeps for at least seven hours. She improves her diet, with increasing emphasis on vegetables, fruits, and whole grains. She also starts a walking program, increasing gradually to a total of three hours per week. After four months, she adds a weekly trip to a gym, where she practices resistance training for about 40 minutes.

Lauren also increases her social activities on weekends and recently accepted an invitation to join a book club. Six months from her initial visit, she notes that although she is still more easily fatigued than most people, she has made significant improvement

REFERENCES

1. Nijrolder I, van der Windt DA, van der Horst HE. Prognosis of fatigue and functioning in primary care: a 1-year follow-up study. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:519-527.

2. Griffith JP, Zarrouf FA. A systematic review of chronic fatigue syndrome: don’t assume it’s depression. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10:120-128.

3. Holmes GP, Kaplan JE, Gantz NM, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a working case definition. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:387-389.

4. Morris G, Maes M. Case definitions and diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome: from clinical consensus to evidence-based case definitions. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34:185-199.

5. Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:953-959.

6. CDC. Chronic fatigue syndrome. www.cdc.gov/cfs/diagnosis/index.html. Accessed December 17, 2015.

7. Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J Intern Med. 2011;270:327-338.

8. Johnston SC, Brenu EW, Hardcastle S, et al. A comparison of health status in patients meeting alternative definitions for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:64.

9. Anderson VR, Jason LA, Hlavaty LE, et al. A review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:147-155.

10. Christley Y, Duffy T, Everall IP, et al. The neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological features of chronic fatigue syndrome: revisiting the enigma. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:353.

11. Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel HH. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528-533.

12. Nater UM, Jones JF, Lin JM, et al. Personality features and personality disorders in chronic fatigue syndrome: a population-based study. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:312-318.

13. Taylor RR, Jason LA, Jahn SC. Chronic fatigue and sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of psychiatric disorders in a community-based sample. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:896-901.

14. Leonard B, Maes M. Mechanistic explanations of how cell-mediated immune activation, inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways and their sequels and concomitants play a role in the pathophysiology of unipolar depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:764-785.

15. DeLuca J, Christodoulou C, Diamond BJ, et al. Working memory deficits in chronic fatigue syndrome: differentiating between speed and accuracy of information processing. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:101-109.

16. Cockshell SJ, Mathias JL. Cognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1253-1267.

17. Komaroff AL, Cho TA. Role of infection and neurologic dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. Semin Neurol. 2011;31:325-337.

18. Naess H, Sundal E, Myhr KM, et al. Postinfectious and chronic fatigue syndromes: clinical experience from a tertiary-referral centre in Norway. In Vivo. 2010;24:185-188.

19. Hickie I, Davenport T, Wakefield D, et al; Dubbo Infection Outcomes Study Group. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2006;333:575.

20. Plioplys AV, Plioplys S. Electron-microscopic investigation of muscle mitochondria in chronic fatigue syndrome.Neuropsychobiology. 1995;32: 175-181.

21. Vernon SD, Whistler T, Cameron B, et al. Preliminary evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction associated with post-infective fatigue after acute infection with Epstein Barr virus. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:15.

22. Miwa K, Fujita M. Fluctuation of serum vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) concentrations during exacerbation and remission phases in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Heart Vessels. 2010;25:319-323.

23. Rosenblum H, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. The common immunogenic etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome: from infections to vaccines via adjuvants to the ASIA syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2011;25:851-863.

24. Vincent A, Brimmer DJ, Whipple MO, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and classification of chronic fatigue syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota as estimated using the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1145-1152.

25. Goroll AH, Mulley AG. Primary Care Medicine: Office Evaluation and Management of the Adult Patient. 7th ed. Morrisville, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

26. Brown RF, Schutte NS. Direct and indirect relationships between emotional intelligence and subjective fatigue in university students. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:585-593.

27. Pigeon WR, Sateia MJ, Ferguson RJ. Distinguishing between excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue: toward improved detection and treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:61-69.

28. Bailes S, Libman E, Baltzan M, et al. Brief and distinct empirical sleepiness and fatigue scales. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:605-613.

29. National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (UK). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy): Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy) in Adults and Children. London, UK: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2007.

30. Lane TJ, Matthews DA, Manu P. The low yield of physical examinations and laboratory investigations of patients with chronic fatigue. Am J Med Sci. 1990;299:313-318.

31. Vaucher P, Druisw PL, Waldvogel S, et al. Effect of iron supplementation on fatigue in nonanemic menstruating women with low ferritin: a randomized controlled trial.CMAJ. 2012;184:1247-1254.

32. US Preventive Services Task Force. Hepatitis C: Screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspshepc.htm. Accessed December 17, 2015.

33. Rolfe A, Burton C. Reassurance after diagnostic testing with a low pretest probability of serious disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:407-416.

34. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671-677.

35. White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, et al; PACE trial management group. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377:823-836.

36. van Weert E, Hoekstra-Weebers J, Otter R, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: predictors and effects of rehabilitation. Oncologist. 2006;11:184-196.

CASE Lauren C, age 35, presents with fatigue, which she says started at least eight months ago and has progressively worsened. The patient, a clerical worker, says she manages to do an adequate job but goes home feeling utterly exhausted each night.

Lauren says she sleeps well, getting more than eight hours of sleep per night on weekends but less than seven hours per night during the week. But no matter how long she sleeps, she never awakens feeling refreshed. Lauren reports that she doesn’t smoke, has no more than four alcoholic drinks per month, and adheres to an “average” diet. She is too tired to exercise.

Lauren is single, with no children. Although she says she has a strong network of family and friends, she increasingly finds she has no energy for socializing. If Lauren were your patient, what would you do?

Fatigue is a common presenting symptom in primary care, accounting for about 5% of adult visits.1 Defined as a generalized lack of energy, fatigue that persists despite adequate rest or is severe enough to disrupt an individual’s ability to participate in key social and/or occupational activities warrants a thorough investigation.

Because fatigue is a nonspecific symptom that may be linked to a number of medical and psychiatric illnesses or to medications used to treat them, determining the cause can be difficult. In about half of all cases, no specific etiology is found.2This review, which includes the elements of a work-up and management strategies for patients presenting with ongoing fatigue, will help you arrive at the appropriate diagnosis and provide optimal treatment.

CHRONIC FATIGUE: DEFINING THE TERMS

A definition of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) was initially published in 1988.3In subsequent years, the term myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) became popular. Although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, ME often refers to patients whose condition is thought to have an infectious cause and for whom postexertional malaise is a hallmark symptom.4

CDC criteria. While several sets of diagnostic criteria for CFS have been developed, the most widely used is that of the CDC, published in 1994 (see Table 1).5,6A diagnosis of CFS is made on the basis of exclusion, subjective clinical interpretation, and patient self-report.

When the first two criteria—fatigue not due to ongoing exertion or other medical conditions that has lasted ≥ 6 months and is severe enough to interfere with daily activities—but fewer than four of the CDC’s eight concurrent symptoms (eg, headache, unrefreshing sleep, and postexertion malaise lasting > 24 h) are present, idiopathic fatigue, rather than CFS, is diagnosed.6

International Consensus Criteria (ICC). In 2011, the ICC for ME were proposed in an effort to provide more specific diagnostic criteria (see Table 2).7The ICC emphasize fatigability, or what the authors identify as “post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion.”

The ICC have not yet been broadly researched. But an Australian study of patients with chronic fatigue found that those who met the ICC definition were sicker and more homogeneous, with significantly lower scores for physical and social functioning and bodily pain, compared with those who fulfilled the CDC criteria alone.8

Continue for common threads of chronic fatigue & neuropsychiatric conditions >>

CHRONIC FATIGUE & NEUROPSYCHIATRIC CONDITIONS: COMMON THREADS

Recent research has made it clear that depression, somatization, and CFS share some biological underpinnings. These include biomarkers for inflammation, cell-mediated immune activation—which may be related to the symptoms of fatigue—autonomic dysfunction, and hyperalgesia.9Evidence suggests that up to two-thirds of patients with CFS also meet the criteria for a psychiatric disorder.10The most common psychiatric conditions are major depressive disorder (MDD), affecting an estimated 22% to 32% of those with CFS; anxiety disorder, affecting about 20%; and somatization disorder, affecting about 10%—at least double the incidence of the general population.10

Others point out, however, that up to half of those with CFS do not have a psychiatric disorder.11A diagnosis of somatization disorder, in particular, depends largely on a subjective interpretation of whether the presenting symptoms have a physical cause.10

CFS and MDD comorbidity. The most widely studied association between CFS and psychiatric disorders involves MDD. Observational studies have found patients with CFS have a lifetime prevalence of MDD of 65%,12,13which is higher than that of patients with other chronic diseases. Overlapping symptoms include fatigue, sleep disturbance, poor concentration, and memory problems. However, those with CFS have fewer symptoms related to anhedonia, poor self-esteem, guilt, and suicidal ideation compared with individuals with MDD.12,13

There are several possible explanations for CFS and MDD comorbidity, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive.10One theory is that CFS is an atypical form of depression; another holds that the disability associated with CFS leads to depression, as is the case with many other chronic illnesses; and a third points to overlapping pathophysiology.10

An emerging body of evidence suggests that CFS and MDD have some common oxidative and nitrosative biochemical pathways. Activated by infection, psychologic stress, and immune disorders, they are believed to have damaging free radical and nitric oxide effects at the cellular level.14The cellular effects can result in fatigue, muscle pain, and flulike malaise.

Cortisol response differs

CFS and MDD might be distinguishable by another pathway—the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. MDD is classically associated with activation and raised cortisol levels, while CFS is consistently associated with impaired HPA axis functioning and reduced cortisol levels.10The majority of patients with CFS report symptoms of cognitive decline, with the acquisition of new verbal learning and information-processing speed particularly likely to be impaired.15

A meta-analysis of 50 studies of patients with CFS showed deficits in attention, memory, and reaction time, but not in fine motor speed, vocabulary, or reasoning.16Autonomic dysfunction has also been observed, including disordered sympathetic activity. The most frequently observed abnormalities on autonomic testing are postural hypotension, tachycardia syndrome, neurally mediated hypotension, and heart rate variability during tilt table testing.16

THE LINK BETWEEN INFECTION AND CFS

Several infectious agents have been associated with ME/CFS, including the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex virus 6, parvovirus, Q fever, and Lyme disease.8,17,18 Most agents that have been linked to ME/CFS are associated with persistent infection and thus incitement of the immune system.

Numerous observational studies17,18have documented postinfectious fatigue syndromes after acute viral and bacterial infections and symptoms suggestive of infection, such as fever, myalgias, and respiratory and gastrointestinal distress. In one prospective Australian study,19investigators identified 253 cases of acute EBV, Ross River virus, and Q fever. Of those 253 patients, 12% went on to develop CFS, with a higher likelihood among those with more severe acute symptoms. No correlation with preexisting psychiatric disorders was found.

Muscle mitochondria studies have demonstrated what appear to be acquired abnormalities in those with CFS.20,21Signs of increased oxidative stress have been found in both blood and muscle samples from patients with CFS, and longitudinal studies suggest that oxidative stress is greatest during periods of clinical exacerbation.22Increased lactate levels suggest increased anaerobic metabolism in the central nervous system consistent with mitochondrial dysfunction. Several studies have demonstrated that exercise can precipitate oxidative stress in patients with CFS, in contrast with healthy controls and controls with other chronic illnesses, suggesting a physiologic basis for their postexertional symptoms.17

Autoinflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants, a rare syndrome associated with vaccine administration, has been linked to postvaccination adverse events, exposure to silicone implants, Gulf War syndrome (related to multiple vaccinations), and macrophagic myofasciitis. All involve exposure to immune adjuvants and have similar clinical manifestations. The corresponding exposures appear to trigger an autoimmune response in susceptible individuals. The hepatitis B vaccine is most often associated with CFS, with symptoms occurring within 90 days of administration.23

Continue for the clinical work-up >>

THE CLINICAL WORK-UP: PUTTING KNOWLEDGE INTO PRACTICE

Familiarity with potential causes of and connections with ME/CFS will help you ensure that patients who say they’re always tired receive a thorough work-up. Start with a medical history, inquiring directly about medical and psychiatric disorders that may contribute to fatigue (see Table 3).5,24,25 Include a medication history as well, to help determine whether the fatigue is drug-related (see Table 4).5,25

What to ask. Determine the onset, course, duration, daily pattern, and impact of fatigue on the patient’s daily life. Inquire, too, about related symptoms of daytime sleepiness, dyspnea on exertion, generalized weakness, and depressed mood. The prominence of any of these rather than fatigue, per se, point to a diagnosis of a chronic illness other than ME/CFS.

Keep in mind, too, that patients with an organ-based medical illness tend to associate their fatigue with activities that they are unable to complete, such as shopping or light housework. In contrast, those with fatigue that is not organ-based typically say that they’re tired all the time. Their fatigue is not necessarily related to exertion, nor does it improve with rest.26

To address this distinction, take a sleep history, assessing both the quality and quantity of the patient’s sleep to determine how it affects symptoms.27 Consider using a questionnaire designed to help distinguish between sleepiness—and a primary sleep disorder—and fatigue,28 such as the Fatigue Severity Scale of Sleep Disorders (www.healthywomen.org/sites/default/files/FatigueSeverityScale.pdf).

What to rule out. In addition to a medical history, the physical examination should be oriented toward ruling out secondary causes of fatigue. In addition to a system-by-system approach to the differential diagnosis, carefully observe the patient’s general appearance, with attention to his or her level of alertness, grooming, and psychomotor agitation or retardation as possible signs of a psychiatric disorder. To rule out neurologic causes, evaluate muscle bulk, tone, and strength; deep tendon reflexes; and sensory and cranial nerves, as well.29

Lab tests to consider. In most cases of ME/CFS, basic studies—complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, blood chemistry, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels—are sufficient. When no medical or psychiatric cause has been found, additional tests may be ordered on a case-by-case basis, although laboratory analysis affects the management of fatigue in less than 5% of such patients.30 Tests to consider include:

• Creatine kinase (for patients who report pain or muscle weakness)

• Pregnancy test (for women of childbearing age)

• Ferritin testing (for young women who might benefit from iron supplementation for levels < 50 ng/mL even if anemia is not present)31

• Hepatitis C screening (recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force for those born between 1945 and 1965)32

• HIV screening and the purified protein derivative test for tuberculosis (based on patient history).

Forego routine testing for other infections

Routine testing for infectious diseases and conditions associated with fatigue, such as EBV or Lyme disease, immune deficiency (eg, immunoglobulins), inflammatory disease (eg, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor), celiac disease, vitamin D deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, or heavy metal toxicity, is unlikely to be helpful.29 Additional testing simply to reassure a worried patient usually does not accomplish that objective.33

Additional studies, referrals to consider. If you suspect that a patient has a sleep disorder, a referral to a sleep clinic to rule out idiopathic sleep disorders, obstructive sleep apnea, or movement disorders that interfere with sleep may be in order. Spirometry and echocardiography may be helpful for some patients. If you suspect peripheral muscle fatigue, a referral for neuromuscular testing is indicated.

Lauren’s medical history reveals that she also has irritable bowel syndrome, which she manages with diet and OTC medication, as needed for constipation or diarrhea. She denies having any other chronic conditions. Her only other symptoms, she reports, are mild upper back pain after spending long hours at the computer and arthralgias in her left knee and both hands. She admits to being “somewhat depressed” in the last few months but denies the presence of anhedonia.

The patient’s physical examination is normal, and her depression screen does not meet the criteria for MDD. Her metabolic chemistry panel, complete blood count, TSH, and sedimentation rate are all normal, as well.

Continue for symptom management and coping strategies >>

SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT AND COPING STRATEGIES

When no specific cause of chronic fatigue is found, the focus shifts from diagnosis to symptom management and coping strategies. This requires engagement with the patient. It is important to acknowledge the existence of his or her symptoms and to reassure the patient that further investigation may be warranted later, should new symptoms emerge. Advise the patient, too, that periods of remission and relapse are likely.

Strategies designed to motivate patient self-management, as well as the formulation of patient-centered treatment plans, have been shown to reduce symptom scores.34 Participation in a support group, as well as frequent follow-up visits with a primary care provider, a behavioral therapist, or both, may help to provide needed psychologic support.

Evidence of the effectiveness of specific therapies for ME/CFS is limited; however, the best-studied approaches are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy.35 Exercise should be low intensity, such as walking or cycling for 30 minutes three times a week, with a gradual increase in duration and frequency over a period of weeks to months. Patients with cancer-related fatigue may benefit from yoga, group therapy, and stress management.36

Associated mood and pain symptoms should be treated, as well. Bupropion, which is somewhat stimulating, may be considered as an initial treatment for patients with depression and clinically significant fatigue.

Other potentially beneficial approaches include a healthy diet, avoidance of more than nominal amounts of alcohol, relative avoidance of caffeine (no more than one cup of a caffeinated beverage in the morning), and stress reduction techniques.

Attention to good sleep hygiene may be especially beneficial, including a regular bedtime routine and sleep schedule, and elimination of bedroom light and noise. Pharmacologic treatments for insomnia should be used with caution, if at all.

Lauren receives a referral for CBT and is scheduled for a return visit in four weeks. At the advice of both her primary care provider and the behavioral therapist, she gradually makes several lifestyle changes. She begins going to bed earlier on weeknights to ensure that she sleeps for at least seven hours. She improves her diet, with increasing emphasis on vegetables, fruits, and whole grains. She also starts a walking program, increasing gradually to a total of three hours per week. After four months, she adds a weekly trip to a gym, where she practices resistance training for about 40 minutes.

Lauren also increases her social activities on weekends and recently accepted an invitation to join a book club. Six months from her initial visit, she notes that although she is still more easily fatigued than most people, she has made significant improvement

REFERENCES

1. Nijrolder I, van der Windt DA, van der Horst HE. Prognosis of fatigue and functioning in primary care: a 1-year follow-up study. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:519-527.

2. Griffith JP, Zarrouf FA. A systematic review of chronic fatigue syndrome: don’t assume it’s depression. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10:120-128.

3. Holmes GP, Kaplan JE, Gantz NM, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a working case definition. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:387-389.

4. Morris G, Maes M. Case definitions and diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome: from clinical consensus to evidence-based case definitions. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34:185-199.

5. Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:953-959.

6. CDC. Chronic fatigue syndrome. www.cdc.gov/cfs/diagnosis/index.html. Accessed December 17, 2015.

7. Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J Intern Med. 2011;270:327-338.

8. Johnston SC, Brenu EW, Hardcastle S, et al. A comparison of health status in patients meeting alternative definitions for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:64.

9. Anderson VR, Jason LA, Hlavaty LE, et al. A review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:147-155.

10. Christley Y, Duffy T, Everall IP, et al. The neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological features of chronic fatigue syndrome: revisiting the enigma. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:353.

11. Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel HH. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528-533.

12. Nater UM, Jones JF, Lin JM, et al. Personality features and personality disorders in chronic fatigue syndrome: a population-based study. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:312-318.

13. Taylor RR, Jason LA, Jahn SC. Chronic fatigue and sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of psychiatric disorders in a community-based sample. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:896-901.

14. Leonard B, Maes M. Mechanistic explanations of how cell-mediated immune activation, inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways and their sequels and concomitants play a role in the pathophysiology of unipolar depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:764-785.

15. DeLuca J, Christodoulou C, Diamond BJ, et al. Working memory deficits in chronic fatigue syndrome: differentiating between speed and accuracy of information processing. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:101-109.

16. Cockshell SJ, Mathias JL. Cognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1253-1267.

17. Komaroff AL, Cho TA. Role of infection and neurologic dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. Semin Neurol. 2011;31:325-337.

18. Naess H, Sundal E, Myhr KM, et al. Postinfectious and chronic fatigue syndromes: clinical experience from a tertiary-referral centre in Norway. In Vivo. 2010;24:185-188.

19. Hickie I, Davenport T, Wakefield D, et al; Dubbo Infection Outcomes Study Group. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2006;333:575.

20. Plioplys AV, Plioplys S. Electron-microscopic investigation of muscle mitochondria in chronic fatigue syndrome.Neuropsychobiology. 1995;32: 175-181.

21. Vernon SD, Whistler T, Cameron B, et al. Preliminary evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction associated with post-infective fatigue after acute infection with Epstein Barr virus. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:15.

22. Miwa K, Fujita M. Fluctuation of serum vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) concentrations during exacerbation and remission phases in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Heart Vessels. 2010;25:319-323.

23. Rosenblum H, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. The common immunogenic etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome: from infections to vaccines via adjuvants to the ASIA syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2011;25:851-863.

24. Vincent A, Brimmer DJ, Whipple MO, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and classification of chronic fatigue syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota as estimated using the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1145-1152.

25. Goroll AH, Mulley AG. Primary Care Medicine: Office Evaluation and Management of the Adult Patient. 7th ed. Morrisville, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

26. Brown RF, Schutte NS. Direct and indirect relationships between emotional intelligence and subjective fatigue in university students. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:585-593.

27. Pigeon WR, Sateia MJ, Ferguson RJ. Distinguishing between excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue: toward improved detection and treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:61-69.

28. Bailes S, Libman E, Baltzan M, et al. Brief and distinct empirical sleepiness and fatigue scales. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:605-613.

29. National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (UK). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy): Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy) in Adults and Children. London, UK: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2007.

30. Lane TJ, Matthews DA, Manu P. The low yield of physical examinations and laboratory investigations of patients with chronic fatigue. Am J Med Sci. 1990;299:313-318.

31. Vaucher P, Druisw PL, Waldvogel S, et al. Effect of iron supplementation on fatigue in nonanemic menstruating women with low ferritin: a randomized controlled trial.CMAJ. 2012;184:1247-1254.

32. US Preventive Services Task Force. Hepatitis C: Screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspshepc.htm. Accessed December 17, 2015.

33. Rolfe A, Burton C. Reassurance after diagnostic testing with a low pretest probability of serious disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:407-416.

34. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671-677.

35. White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, et al; PACE trial management group. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377:823-836.

36. van Weert E, Hoekstra-Weebers J, Otter R, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: predictors and effects of rehabilitation. Oncologist. 2006;11:184-196.