User login

The aging of the U.S. population has led to an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with cancer each year. Fortunately, advances in screening, detection, and treatments have contributed to an improvement in cancer survival rates during the past few decades. More than 1.6 million new cases of cancer are expected to be diagnosed in 2014. It is estimated that there are currently 14 million cancer survivors, and the number of survivors by 2022 is expected to be 18 million.1,2

The growing number of cancer survivors is exceeding the ability of the cancer care system to meet the demand.3 Many primary care providers (PCPs) lack the confidence to provide cancer surveillance for survivors, but at the same time, patients and physicians continue to expect that PCPs will play a substantial role in general preventive health and in treating other medical problems.4 These conditions make it critical that at a minimum, survivorship care is integrated between oncology and primary care teams through a systematic, coordinated plan.5 This integration is especially important for the vulnerable population of veterans who are cancer survivors, as they have additional survivorship needs.

The purpose of this article is to assist other VA health care providers in establishing a cancer survivorship program to address the unique needs of veterans not only during active treatment, but after their initial treatment is completed. Described are the unique needs of veterans who are cancer survivors and the development and implementation of a cancer survivorship program at a large metropolitan VAMC, which is grounded in VA and national guidelines and evidence-based cancer care. Lessons learned and recommendations for other VA programs seeking to improve coordination of care for veteran cancer survivors are presented.

Cancer Survivorship

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, identified the importance of providing quality survivorship care to those “living with, through, and beyond a diagnosis of cancer.”6,7 The period of survivorship extends from the time of diagnosis, through treatment, long-term survival, and end-of-life.8,9 Although there are several definitions of cancer survivor, the most widely accepted definition is one who has been diagnosed with cancer, regardless of their position on the disease trajectory.8

The complex needs of cancer survivors encompass physical, psychological, social, and spiritual concerns across the disease trajectory.3 Cancer survivors who are also veterans have additional needs and risk factors related to their service that can make survivorship care more challenging.10 Veterans tend to be older compared with the age of the general population, have more comorbid conditions, and many have combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), all of which can complicate the survivorship experience.11

The first challenge for veteran cancer survivors is in the term cancer survivor, which may take on a different meaning for a veteran when compared with a civilian. For some civilians and veterans, survivor is a constant reminder of having had cancer. There are some veterans who prefer not to be called survivors, because they do not feel worthy of this terminology. They believe they have not struggled enough to self-identify as a survivor and that survivorship is “something to be earned, following a physically grueling experience.”12

The meaning of the word survivor may even be culturally linked to the population of veterans who have survived a life-threatening combat experience. More research is needed to understand the veteran cancer survivorship experience. The meaning of survivorship must be explored with each veteran, as it may influence his or her adherence to a survivorship plan of care.

Veterans make up a unique subset of cancer survivors, in part because of risk factors associated with their service. Many veterans developed cancer as a result of their military exposure to toxic chemicals and radiation. To date, VA recognizes that chronic B-cell leukemias, Hodgkin disease, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, prostate cancer, respiratory cancers, and soft tissue sarcomas are all presumptive diseases related to Agent Orange exposure.13 There are other substances also presumed to increase the risk of certain cancers in veterans who have had ionizing radiation exposure.14 There is still much to learn regarding veterans who served during the Gulf War, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation Iraqi Freedom.15,16

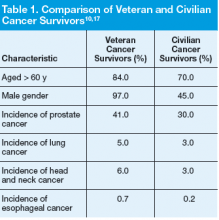

In a comparison of VA data files with U.S. SEER data files from 2007, researchers identified differences in characteristics between veteran cancer survivors and civilian cancer survivors.17 In addition to increased exposure risks, the veteran cancer survivor population is older than the general cancer survivorship population and is mostly male.17 Veterans’ comorbid conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, Parkinson disease, and peripheral neuropathy, which may be service related, complicate survivorship.17 These characteristics (age, gender, exposure risks, and comorbid conditions) influence the type of cancer diagnosed and treatment options, and they may ultimately impact survivorship needs

(Table 1).

The prevalence of mental health issues in the veteran population is significant.18 Posttraumatic stress disorder affects 7% to 8% of the general population at some point during their lifetime and as many as 16% of those returning from military deployment.19 In a predominantly

male veteran study correlating combat PTSD with cancerrelated PTSD, about half the participants (n = 170) met PTSD Criterion A, viewing their cancer as a traumatic experience.20 Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, and addictive disease all must be addressed in the survivorship plan of care.

Poor mental health has been linked to increased morbidity and mortality and can limit the veteran’s ability to participate in health promotion and medical care.21 Distress related to cancer is well recognized in the civilian population.22,23 Veterans are at risk for moderate-tosevere disabling distress, especially when the cancer is associated with their military service. Vietnam veterans who have a diagnosis of cancer report that they have already served their time and are now serving it again, having to wage a battle on cancer and undergo difficult treatments and associated adverse effects (AEs).24 It is important to note, however, that some veterans have developed strong coping skills, which gives them strength and resilience for the survivorship experience.25

Other factors also contribute to veterans’ unique survivorship needs. Many veterans have limited social and/or economic resources, making it difficult to receive cancer treatment and follow recommendations for a healthful lifestyle as a cancer survivor. Demographics from the VA have illustrated that many veterans have a limited support system (65% do not have a spouse), and many have low incomes.26 Although veterans comprise about 11% of the general population, they make up 26% of the homeless population.26 It is estimated that 260,000 veterans are homeless at some time during the course of a year, and of these, 45% have mental health issues and 70% have substance abuse problems.27 Basic needs such as housing, running water, heat and electricity, and nutrition must be met in order to prevent infection during treatment, maximize the benefit, and reduce the risks associated with treatment. Transportation issues can make it challenging to travel to medical centers for cancer surveillance following treatment.

Models of Care

As defined in the aforementioned IOM report, multiple models of survivorship care have surfaced over the years.6 Much that was originally seen and implemented in adult cancer survivorship was known from pediatric cancer care. Early models that surfaced included shared care models, nurse-led models, and tertiary survivorship clinics. Each model has its strengths and disadvantages.

The shared care model of survivorship involves a sharing of the responsibility for the survivor among different specialties, potentially at different facilities, and the primary care team. Typically, the PCP refers the patient to the oncologist when cancer is suspected or diagnosed. The primary care team continues to provide routine health maintenance and manages other health problems while the oncology team provides cancer care. The patient is transitioned back to the primary care team with a survivorship care plan (SCP) at 1 to 2 years after completion of cancer therapy or at the discretion of the oncology team.28 For

this model to work, the PCP must be willing to take on this responsibility, and there must be a coordinated effort for seamless communication between teams, which can be potentially challenging.

Nurse-led programs emerged in the pediatric populations. Pediatric nurse-led clinics assume care of the patient after active treatment to manage long-term AEs of cancer treatments, symptom management, care planning, and education. A comprehensive review of the literature identified that “nurse-led follow-up services are acceptable, appropriate, and effective.”6 Barriers to this model of care include a shortage of trained oncology nurses and a preference for physician follow-up by some cancer survivors who want the security of their oncologist for ongoing, long-term care.6

Survivorship follow-up clinics, a tertiary model of care, have been implemented at some larger academic centers. These clinics focus on cancer survivorship and are often separate from other routine health care visits. Typically, these clinics include multiple specialties and are often disease-specific. These types of clinics pose a different set of challenges regarding duplication of services and reimbursement issues.

As of yet, no model has been proven more effective than the others. Each institution and patient population may not lend themselves to a one-size-fits-all model. There may be different models of care needed, based on patient population. Regardless of the model selected, individualized survivorship care plans are an essential component of quality cancer survivorship care.

Addessing Survivorship Care

In 2009, 5 interdisciplinary leaders in VA cancer care (Ellen Ballard, RN; David Haggstrom, MD, MAS; Veronica Reis, PhD; Mark Detzer, PhD; and Tina Gill, MA) attended a breakout session on psychosocial oncology at the Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and most members of this team participated in the 2009-2012 VHA Cancer Care Collaboratives to improve the timeliness and quality of care for veterans who were cancer patients. Dr. Haggstrom and Ms. Ballard developed a SharePoint site for the Survivorship Special Interest Group (SIG) members through the Loma Linda VAMC in California. The SIG workgroup then built the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit, composed of

5 critical tools (Figure).

In July 2012, the VA Cancer Survivorship Toolkit content was disseminated at AVAHO and launched behind the VA firewall. It subsequently received accolades from the national program director for VHA Oncology and was listed on the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) Best Practices website. The toolkit is accessible to all VA programs, and suggestions for new content can be submitted directly on the site (Figure).

The development of a SCP began in late 2011 when SIG members collected examples of SCPs from leading organizations. The members compared this content with the IOM recommendations for SCPs and developed a template. The template was programmed for the VHA computerized patient record system (CPRS) and placed on the internal VA toolkit website. The template included the treatment summary and care plan. The treatment summary portion included the diagnosis and tumor characteristics, diagnostic tests used, dates and types of treatment, chemoprevention or maintenance treatments, supportive services required, the surveillance plan, and signs of recurrence. The care plan portion provided information on the likely course of recovery and a checklist for common long-term AEs in the areas of psychological distress, financial and practical effects, and physical effects. Also included was information about referral, health behaviors, late effects that may develop, contact information, and general resource information.

The computer applications coordinator at any VA can download the template from the toolkit onto their CPRS, and the template can then be brought into any progress note. Individual sites may also edit the template to suit specific needs. The SCP can be completed by any clinician with the appropriate clinical competencies. To date, > 50 sites have downloaded the SCP template for use.

Cancer Survivorship Clinic

At the Louis Stokes Cleveland (LSC) VAMC, a nurse-led model of a cancer survivorship clinic was established with an expert nurse practitioner (NP). A major catalyst for the development of this clinic was the receipt of a Specialty Care Education Center of Excellence, funded by the Offices of Specialty Care and Academic Affiliations. A priority of this project was the implementation of survivorship care for every veteran with a cancer diagnosis. A system redesign was implemented to deliver quality, cost-effective, patient-centered cancer care within an interprofessional, team-based practice. This clinic is imbedded within an interdisciplinary clinic setting where the NP works in close collaboration with the medical and surgical oncologists as well as providers from mental health, social work, nutrition, physical therapy, and others.

The first patients to receive survivorship care in this new model from the time of their diagnosis were veterans with breast cancer, sarcoma, melanoma, and lymphomas. Veterans are followed jointly by the NP and the medical and surgical oncologists during active treatment. The NP provides physical symptom assessment and management for patients both during and after treatment.

At the end of active treatment, patient visits are alternated between oncology physicians and the survivorship NP for 5 years. The timeline for follow-up visits is based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for each cancer type but then individualized based on patient need.29 During this 5-year time period, patients under active surveillance whose conditions have been stable are seen by the NP. Any concerning symptoms are immediately relayed to the primary oncologist or surgical oncologist, often the same day, and patients can be seen the same day if necessary, to improve coordination and access to services.

A unique focus of the clinic is the integration of health promotion and risk reduction that coincides with the active surveillance plan. This transition of active surveillance patients to the NP-led survivorship clinic not only opens access to newly diagnosed cancer patients to be seen by the oncologist, but also allows for seamless transition and coordination to active surveillance. Within the clinic structure, patients receive patient navigation beginning with a cancer concern; patients also receive screening for psychosocial distress at the time of diagnosis and at every visit. Patient navigation and distress screening are both considered essential elements to survivorship care in the most recent CoC guidelines.30 The survivorship NP keeps the primary care team up-to-date regarding patient care across the disease trajectory by alerting them to updates electronically in the CPRS in real time.

Survivorship Care Plan

A focus of the clinic has also been on the implementation of a formal SCP to be completed 3 months after the conclusion of active treatment. The formal SCP was downloaded from the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit and is composed of a 3-part summary. The 3 parts consist of the treatment summary, the plan for rehabilitation, and the plan for the future. The first section of the SCP is completed by the medical oncologist as a summary of treatment received by the veteran. The summary of treatment section is reviewed and discussed with the veteran survivor at the visit, and the second and third sections are completed during the 3-month follow-up visit with the veteran.

Success and Areas for Improvement

The survivorship clinic has been well received by veterans. Patient satisfaction scores have been overwhelmingly positive. Veterans appreciate and feel comfortable knowing their providers from the beginning of diagnosis along the entire disease trajectory. They know that if problems arise, the survivorship NP has direct access to the medical or surgical oncologist for immediate review.

The difficult challenge for the cancer care providers is to know when is the right time to transition care back to the PCP. Transitions of care often come with high anxiety and a sense of loss for the veteran. The 5-year survival mark is not always the appropriate transition time for some veterans. Those with extensive physical and mental health issues may need continuity of care and continued support from the oncology team.

The SCP has presented challenges in terms of when to complete and who should complete the form. There has also been concern over the length of the summary, how long it will take to complete the document, and which summary template to use. Areas for improvement with the template could potentially be to automate population of the chemotherapy and radiation summaries. Some software packages are available, but they are costly. Another issue with external software is getting it accepted by VHA and incorporated into the CPRS.

Recommendations

Many cancer programs are struggling to provide highquality survivorship care. The CoC, recognizing the challenges programs are having implementing survivorship care, has extended the accreditation requirement for full implementation from 2015 to 2019.31

The following recommendations should be considered for the successful implementation of a new survivorship program:

- Collect information from multiple resources to guide the establishment of the survivorship clinic;

- Become familiar with the IOM From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition;6

- Understand local issues and barriers specific to your care delivery system;

- Collaborate with key stakeholders from multiple specialties to gain momentum and buy-in;

- Hold regular meetings with stakeholders as well as leadership to identify and remove barriers to the clinic success;

- Join the VA Survivorship SIG to collaborate with other sites who have already started to pilot survivorship programs and discuss barriers to and successes of programs so as to not reinvent the wheel;

- Utilize the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit;

- Download the SCP;

- Establish a close partnership with your local cancer committee; and

- Collect and report data to show effectiveness and need.

All these strategies were vital to the success of the LSCVAMC survivorship program.

Summary

The VA is uniquely positioned to be a leader in highquality, comprehensive, and veteran-centered cancer survivorship care in the years ahead. The close relationship between specialty and primary care allows for smooth continuity of care and easy transitions between oncology and primary care. The comprehensive CPRS allows easy accessibility to information for the entire health care team. The Cancer Survivorship Toolkit provides a template of the survivorship care plan for the veteran and his or her health care providers.

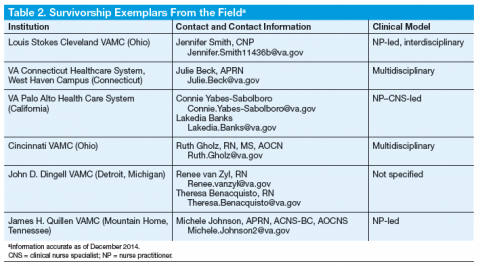

The LSCVAMC is one of many VA institutions implementing quality care for cancer survivors and can serve as a role model for other VA programs initiating the survivorship care process (Table 2).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2014.

2. Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Levit LA, Balough EP, Nass SJ, Ganz PA, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

3. Stricker CT, O’Brien M. Implementing the commission on cancer standards for survivorship care plans. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;(suppl 18):15-22.

4. Cowens-Alvarado R, Sharpe K, Pratt-Chapman M, et al. Advancing survivorship care through the National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center: Developing American Cancer Society guidelines for primary care providers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(3):147-150.

5. Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2489-2495.

6. Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006.

7. Clark EJ, Stovall EL, Leigh S, Siu AL, Austin DK, Rowland JH, eds. Imperatives for Quality Cancer Care: Access, Advocacy, Action, and Accountability. Silver Spring, MD: National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship; 1996.

8. National Cancer Institute. Survivorship. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms Website. http://www.cancer.gov/dictionary?CdrID=445089. Accessed December 3, 2014.

9. Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220-241.

10. Moye J, Schuster JL, Latini DM, Naik AD. The future of cancer survivorship care for veterans. Fed Pract. 2010;27(3):36-43.

11. Naik AD, Martin LA, Karel M, et al. Cancer survivor rehabilitation and recovery: Protocol for the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vet-CaRes). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:93.

12. Beehler GP, Rodriques AE, Kay MA, Kiviniemi MT, Steinbrenner L. Lasting impact: Understanding the psychosocial implications of cancer among military veterans. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013:31(4):430-450.

13. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ diseases associated with Agent Orange. Public Health Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/agentorange/conditions/index.asp. Updated December 30, 2013. Accessed December3, 2014.

14. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Radiation. Public Health Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/radiation/index.asp. Updated December 31, 2013. Accessed December 3, 2014.

15. Cohen BE, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Kim S, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA non-mental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

16. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Gulf War veterans’ illnesses. Public Health Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/gulfwar/index.asp. Updated November 7, 2014. Accessed December 3, 2014.

17. National Cancer Institute. Cancer query systems. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Website. http://seer.cancer.gov/canques/index.html. Accessed December 3, 2014.

18. Suicide in the military: Army-NIH funded study points to risk and protective factors [news release]. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; March 3, 2014. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2014/suicide-in-the-military-army-nih-funded-study-points-to-risk-and-protective-factors.shtml. Accessed December 3, 2014.

19. Gates MA, Holowka DW, Vasterling JJ, Keane TM, Marx BP, Rosen RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans and military personnel: Epidemiology, screening, and case recognition. Psychol Serv. 2012;9(4):361-382.

20. Mulligan EA, Schuster Wachen J, Naik AD, Gosian J, Moye J. Cancer as a criterion a traumatic stressor for veterans: Prevalence and correlates. Psychol Trauma. 2014;6(suppl 1):S73-S81.

21. Musuuza JS, Sherman ME, Knudsen KJ, Sweeney HA, Tyler CV, Koroukian SM. Analyzing excess mortality from cancer among individuals with mental illness. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2469-2476.

22. Zabora J, Macmurray L. The history of psychosocial screening among cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013:30(6):625-635.

23. Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. Distress management: Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010:8(4):448-485.

24. Grassman DL. The Hero Within. St. Petersburg, FL: Vandamere Press; 2012.

25. Jahn AL, Herman L, Schuster J, Naik A, Moye J. Distress and resilience after cancer

in veterans. Res Hum Dev. 2012;9(3):229-247.

26. National Association of Social Workers. Social workers speak on veterans issues June 2009. National Association of Social Workers Website. http://www.naswdc.org/pressroom/2009/Social%20Work%20Veterans%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2014.

27. Homeless. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.va.gov/homeless. Accessed December 3, 2014.

28. Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117-5124.

29. NCCN Guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Website. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#site. Accessed December 3, 2014.

30. American College of Surgeons, Commission on Cancer. Cancer program standards 2012, version 1.2.1: Ensuring patient-centered care. https://www.facs.org/~/media/file/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx. Published January 21, 2014. Accessed December 3, 2014.

31. Accreditation committee clarifications for standard 3.3 survivorship care plan. American College of Surgeons Website. https://www.facs.org/publications/newsletters/coc-source/special-source/standard33. Published September 9, 2014. Accessed December 3, 2014.

The aging of the U.S. population has led to an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with cancer each year. Fortunately, advances in screening, detection, and treatments have contributed to an improvement in cancer survival rates during the past few decades. More than 1.6 million new cases of cancer are expected to be diagnosed in 2014. It is estimated that there are currently 14 million cancer survivors, and the number of survivors by 2022 is expected to be 18 million.1,2

The growing number of cancer survivors is exceeding the ability of the cancer care system to meet the demand.3 Many primary care providers (PCPs) lack the confidence to provide cancer surveillance for survivors, but at the same time, patients and physicians continue to expect that PCPs will play a substantial role in general preventive health and in treating other medical problems.4 These conditions make it critical that at a minimum, survivorship care is integrated between oncology and primary care teams through a systematic, coordinated plan.5 This integration is especially important for the vulnerable population of veterans who are cancer survivors, as they have additional survivorship needs.

The purpose of this article is to assist other VA health care providers in establishing a cancer survivorship program to address the unique needs of veterans not only during active treatment, but after their initial treatment is completed. Described are the unique needs of veterans who are cancer survivors and the development and implementation of a cancer survivorship program at a large metropolitan VAMC, which is grounded in VA and national guidelines and evidence-based cancer care. Lessons learned and recommendations for other VA programs seeking to improve coordination of care for veteran cancer survivors are presented.

Cancer Survivorship

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, identified the importance of providing quality survivorship care to those “living with, through, and beyond a diagnosis of cancer.”6,7 The period of survivorship extends from the time of diagnosis, through treatment, long-term survival, and end-of-life.8,9 Although there are several definitions of cancer survivor, the most widely accepted definition is one who has been diagnosed with cancer, regardless of their position on the disease trajectory.8

The complex needs of cancer survivors encompass physical, psychological, social, and spiritual concerns across the disease trajectory.3 Cancer survivors who are also veterans have additional needs and risk factors related to their service that can make survivorship care more challenging.10 Veterans tend to be older compared with the age of the general population, have more comorbid conditions, and many have combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), all of which can complicate the survivorship experience.11

The first challenge for veteran cancer survivors is in the term cancer survivor, which may take on a different meaning for a veteran when compared with a civilian. For some civilians and veterans, survivor is a constant reminder of having had cancer. There are some veterans who prefer not to be called survivors, because they do not feel worthy of this terminology. They believe they have not struggled enough to self-identify as a survivor and that survivorship is “something to be earned, following a physically grueling experience.”12

The meaning of the word survivor may even be culturally linked to the population of veterans who have survived a life-threatening combat experience. More research is needed to understand the veteran cancer survivorship experience. The meaning of survivorship must be explored with each veteran, as it may influence his or her adherence to a survivorship plan of care.

Veterans make up a unique subset of cancer survivors, in part because of risk factors associated with their service. Many veterans developed cancer as a result of their military exposure to toxic chemicals and radiation. To date, VA recognizes that chronic B-cell leukemias, Hodgkin disease, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, prostate cancer, respiratory cancers, and soft tissue sarcomas are all presumptive diseases related to Agent Orange exposure.13 There are other substances also presumed to increase the risk of certain cancers in veterans who have had ionizing radiation exposure.14 There is still much to learn regarding veterans who served during the Gulf War, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation Iraqi Freedom.15,16

In a comparison of VA data files with U.S. SEER data files from 2007, researchers identified differences in characteristics between veteran cancer survivors and civilian cancer survivors.17 In addition to increased exposure risks, the veteran cancer survivor population is older than the general cancer survivorship population and is mostly male.17 Veterans’ comorbid conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, Parkinson disease, and peripheral neuropathy, which may be service related, complicate survivorship.17 These characteristics (age, gender, exposure risks, and comorbid conditions) influence the type of cancer diagnosed and treatment options, and they may ultimately impact survivorship needs

(Table 1).

The prevalence of mental health issues in the veteran population is significant.18 Posttraumatic stress disorder affects 7% to 8% of the general population at some point during their lifetime and as many as 16% of those returning from military deployment.19 In a predominantly

male veteran study correlating combat PTSD with cancerrelated PTSD, about half the participants (n = 170) met PTSD Criterion A, viewing their cancer as a traumatic experience.20 Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, and addictive disease all must be addressed in the survivorship plan of care.

Poor mental health has been linked to increased morbidity and mortality and can limit the veteran’s ability to participate in health promotion and medical care.21 Distress related to cancer is well recognized in the civilian population.22,23 Veterans are at risk for moderate-tosevere disabling distress, especially when the cancer is associated with their military service. Vietnam veterans who have a diagnosis of cancer report that they have already served their time and are now serving it again, having to wage a battle on cancer and undergo difficult treatments and associated adverse effects (AEs).24 It is important to note, however, that some veterans have developed strong coping skills, which gives them strength and resilience for the survivorship experience.25

Other factors also contribute to veterans’ unique survivorship needs. Many veterans have limited social and/or economic resources, making it difficult to receive cancer treatment and follow recommendations for a healthful lifestyle as a cancer survivor. Demographics from the VA have illustrated that many veterans have a limited support system (65% do not have a spouse), and many have low incomes.26 Although veterans comprise about 11% of the general population, they make up 26% of the homeless population.26 It is estimated that 260,000 veterans are homeless at some time during the course of a year, and of these, 45% have mental health issues and 70% have substance abuse problems.27 Basic needs such as housing, running water, heat and electricity, and nutrition must be met in order to prevent infection during treatment, maximize the benefit, and reduce the risks associated with treatment. Transportation issues can make it challenging to travel to medical centers for cancer surveillance following treatment.

Models of Care

As defined in the aforementioned IOM report, multiple models of survivorship care have surfaced over the years.6 Much that was originally seen and implemented in adult cancer survivorship was known from pediatric cancer care. Early models that surfaced included shared care models, nurse-led models, and tertiary survivorship clinics. Each model has its strengths and disadvantages.

The shared care model of survivorship involves a sharing of the responsibility for the survivor among different specialties, potentially at different facilities, and the primary care team. Typically, the PCP refers the patient to the oncologist when cancer is suspected or diagnosed. The primary care team continues to provide routine health maintenance and manages other health problems while the oncology team provides cancer care. The patient is transitioned back to the primary care team with a survivorship care plan (SCP) at 1 to 2 years after completion of cancer therapy or at the discretion of the oncology team.28 For

this model to work, the PCP must be willing to take on this responsibility, and there must be a coordinated effort for seamless communication between teams, which can be potentially challenging.

Nurse-led programs emerged in the pediatric populations. Pediatric nurse-led clinics assume care of the patient after active treatment to manage long-term AEs of cancer treatments, symptom management, care planning, and education. A comprehensive review of the literature identified that “nurse-led follow-up services are acceptable, appropriate, and effective.”6 Barriers to this model of care include a shortage of trained oncology nurses and a preference for physician follow-up by some cancer survivors who want the security of their oncologist for ongoing, long-term care.6

Survivorship follow-up clinics, a tertiary model of care, have been implemented at some larger academic centers. These clinics focus on cancer survivorship and are often separate from other routine health care visits. Typically, these clinics include multiple specialties and are often disease-specific. These types of clinics pose a different set of challenges regarding duplication of services and reimbursement issues.

As of yet, no model has been proven more effective than the others. Each institution and patient population may not lend themselves to a one-size-fits-all model. There may be different models of care needed, based on patient population. Regardless of the model selected, individualized survivorship care plans are an essential component of quality cancer survivorship care.

Addessing Survivorship Care

In 2009, 5 interdisciplinary leaders in VA cancer care (Ellen Ballard, RN; David Haggstrom, MD, MAS; Veronica Reis, PhD; Mark Detzer, PhD; and Tina Gill, MA) attended a breakout session on psychosocial oncology at the Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and most members of this team participated in the 2009-2012 VHA Cancer Care Collaboratives to improve the timeliness and quality of care for veterans who were cancer patients. Dr. Haggstrom and Ms. Ballard developed a SharePoint site for the Survivorship Special Interest Group (SIG) members through the Loma Linda VAMC in California. The SIG workgroup then built the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit, composed of

5 critical tools (Figure).

In July 2012, the VA Cancer Survivorship Toolkit content was disseminated at AVAHO and launched behind the VA firewall. It subsequently received accolades from the national program director for VHA Oncology and was listed on the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) Best Practices website. The toolkit is accessible to all VA programs, and suggestions for new content can be submitted directly on the site (Figure).

The development of a SCP began in late 2011 when SIG members collected examples of SCPs from leading organizations. The members compared this content with the IOM recommendations for SCPs and developed a template. The template was programmed for the VHA computerized patient record system (CPRS) and placed on the internal VA toolkit website. The template included the treatment summary and care plan. The treatment summary portion included the diagnosis and tumor characteristics, diagnostic tests used, dates and types of treatment, chemoprevention or maintenance treatments, supportive services required, the surveillance plan, and signs of recurrence. The care plan portion provided information on the likely course of recovery and a checklist for common long-term AEs in the areas of psychological distress, financial and practical effects, and physical effects. Also included was information about referral, health behaviors, late effects that may develop, contact information, and general resource information.

The computer applications coordinator at any VA can download the template from the toolkit onto their CPRS, and the template can then be brought into any progress note. Individual sites may also edit the template to suit specific needs. The SCP can be completed by any clinician with the appropriate clinical competencies. To date, > 50 sites have downloaded the SCP template for use.

Cancer Survivorship Clinic

At the Louis Stokes Cleveland (LSC) VAMC, a nurse-led model of a cancer survivorship clinic was established with an expert nurse practitioner (NP). A major catalyst for the development of this clinic was the receipt of a Specialty Care Education Center of Excellence, funded by the Offices of Specialty Care and Academic Affiliations. A priority of this project was the implementation of survivorship care for every veteran with a cancer diagnosis. A system redesign was implemented to deliver quality, cost-effective, patient-centered cancer care within an interprofessional, team-based practice. This clinic is imbedded within an interdisciplinary clinic setting where the NP works in close collaboration with the medical and surgical oncologists as well as providers from mental health, social work, nutrition, physical therapy, and others.

The first patients to receive survivorship care in this new model from the time of their diagnosis were veterans with breast cancer, sarcoma, melanoma, and lymphomas. Veterans are followed jointly by the NP and the medical and surgical oncologists during active treatment. The NP provides physical symptom assessment and management for patients both during and after treatment.

At the end of active treatment, patient visits are alternated between oncology physicians and the survivorship NP for 5 years. The timeline for follow-up visits is based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for each cancer type but then individualized based on patient need.29 During this 5-year time period, patients under active surveillance whose conditions have been stable are seen by the NP. Any concerning symptoms are immediately relayed to the primary oncologist or surgical oncologist, often the same day, and patients can be seen the same day if necessary, to improve coordination and access to services.

A unique focus of the clinic is the integration of health promotion and risk reduction that coincides with the active surveillance plan. This transition of active surveillance patients to the NP-led survivorship clinic not only opens access to newly diagnosed cancer patients to be seen by the oncologist, but also allows for seamless transition and coordination to active surveillance. Within the clinic structure, patients receive patient navigation beginning with a cancer concern; patients also receive screening for psychosocial distress at the time of diagnosis and at every visit. Patient navigation and distress screening are both considered essential elements to survivorship care in the most recent CoC guidelines.30 The survivorship NP keeps the primary care team up-to-date regarding patient care across the disease trajectory by alerting them to updates electronically in the CPRS in real time.

Survivorship Care Plan

A focus of the clinic has also been on the implementation of a formal SCP to be completed 3 months after the conclusion of active treatment. The formal SCP was downloaded from the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit and is composed of a 3-part summary. The 3 parts consist of the treatment summary, the plan for rehabilitation, and the plan for the future. The first section of the SCP is completed by the medical oncologist as a summary of treatment received by the veteran. The summary of treatment section is reviewed and discussed with the veteran survivor at the visit, and the second and third sections are completed during the 3-month follow-up visit with the veteran.

Success and Areas for Improvement

The survivorship clinic has been well received by veterans. Patient satisfaction scores have been overwhelmingly positive. Veterans appreciate and feel comfortable knowing their providers from the beginning of diagnosis along the entire disease trajectory. They know that if problems arise, the survivorship NP has direct access to the medical or surgical oncologist for immediate review.

The difficult challenge for the cancer care providers is to know when is the right time to transition care back to the PCP. Transitions of care often come with high anxiety and a sense of loss for the veteran. The 5-year survival mark is not always the appropriate transition time for some veterans. Those with extensive physical and mental health issues may need continuity of care and continued support from the oncology team.

The SCP has presented challenges in terms of when to complete and who should complete the form. There has also been concern over the length of the summary, how long it will take to complete the document, and which summary template to use. Areas for improvement with the template could potentially be to automate population of the chemotherapy and radiation summaries. Some software packages are available, but they are costly. Another issue with external software is getting it accepted by VHA and incorporated into the CPRS.

Recommendations

Many cancer programs are struggling to provide highquality survivorship care. The CoC, recognizing the challenges programs are having implementing survivorship care, has extended the accreditation requirement for full implementation from 2015 to 2019.31

The following recommendations should be considered for the successful implementation of a new survivorship program:

- Collect information from multiple resources to guide the establishment of the survivorship clinic;

- Become familiar with the IOM From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition;6

- Understand local issues and barriers specific to your care delivery system;

- Collaborate with key stakeholders from multiple specialties to gain momentum and buy-in;

- Hold regular meetings with stakeholders as well as leadership to identify and remove barriers to the clinic success;

- Join the VA Survivorship SIG to collaborate with other sites who have already started to pilot survivorship programs and discuss barriers to and successes of programs so as to not reinvent the wheel;

- Utilize the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit;

- Download the SCP;

- Establish a close partnership with your local cancer committee; and

- Collect and report data to show effectiveness and need.

All these strategies were vital to the success of the LSCVAMC survivorship program.

Summary

The VA is uniquely positioned to be a leader in highquality, comprehensive, and veteran-centered cancer survivorship care in the years ahead. The close relationship between specialty and primary care allows for smooth continuity of care and easy transitions between oncology and primary care. The comprehensive CPRS allows easy accessibility to information for the entire health care team. The Cancer Survivorship Toolkit provides a template of the survivorship care plan for the veteran and his or her health care providers.

The LSCVAMC is one of many VA institutions implementing quality care for cancer survivors and can serve as a role model for other VA programs initiating the survivorship care process (Table 2).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The aging of the U.S. population has led to an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with cancer each year. Fortunately, advances in screening, detection, and treatments have contributed to an improvement in cancer survival rates during the past few decades. More than 1.6 million new cases of cancer are expected to be diagnosed in 2014. It is estimated that there are currently 14 million cancer survivors, and the number of survivors by 2022 is expected to be 18 million.1,2

The growing number of cancer survivors is exceeding the ability of the cancer care system to meet the demand.3 Many primary care providers (PCPs) lack the confidence to provide cancer surveillance for survivors, but at the same time, patients and physicians continue to expect that PCPs will play a substantial role in general preventive health and in treating other medical problems.4 These conditions make it critical that at a minimum, survivorship care is integrated between oncology and primary care teams through a systematic, coordinated plan.5 This integration is especially important for the vulnerable population of veterans who are cancer survivors, as they have additional survivorship needs.

The purpose of this article is to assist other VA health care providers in establishing a cancer survivorship program to address the unique needs of veterans not only during active treatment, but after their initial treatment is completed. Described are the unique needs of veterans who are cancer survivors and the development and implementation of a cancer survivorship program at a large metropolitan VAMC, which is grounded in VA and national guidelines and evidence-based cancer care. Lessons learned and recommendations for other VA programs seeking to improve coordination of care for veteran cancer survivors are presented.

Cancer Survivorship

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, identified the importance of providing quality survivorship care to those “living with, through, and beyond a diagnosis of cancer.”6,7 The period of survivorship extends from the time of diagnosis, through treatment, long-term survival, and end-of-life.8,9 Although there are several definitions of cancer survivor, the most widely accepted definition is one who has been diagnosed with cancer, regardless of their position on the disease trajectory.8

The complex needs of cancer survivors encompass physical, psychological, social, and spiritual concerns across the disease trajectory.3 Cancer survivors who are also veterans have additional needs and risk factors related to their service that can make survivorship care more challenging.10 Veterans tend to be older compared with the age of the general population, have more comorbid conditions, and many have combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), all of which can complicate the survivorship experience.11

The first challenge for veteran cancer survivors is in the term cancer survivor, which may take on a different meaning for a veteran when compared with a civilian. For some civilians and veterans, survivor is a constant reminder of having had cancer. There are some veterans who prefer not to be called survivors, because they do not feel worthy of this terminology. They believe they have not struggled enough to self-identify as a survivor and that survivorship is “something to be earned, following a physically grueling experience.”12

The meaning of the word survivor may even be culturally linked to the population of veterans who have survived a life-threatening combat experience. More research is needed to understand the veteran cancer survivorship experience. The meaning of survivorship must be explored with each veteran, as it may influence his or her adherence to a survivorship plan of care.

Veterans make up a unique subset of cancer survivors, in part because of risk factors associated with their service. Many veterans developed cancer as a result of their military exposure to toxic chemicals and radiation. To date, VA recognizes that chronic B-cell leukemias, Hodgkin disease, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, prostate cancer, respiratory cancers, and soft tissue sarcomas are all presumptive diseases related to Agent Orange exposure.13 There are other substances also presumed to increase the risk of certain cancers in veterans who have had ionizing radiation exposure.14 There is still much to learn regarding veterans who served during the Gulf War, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation Iraqi Freedom.15,16

In a comparison of VA data files with U.S. SEER data files from 2007, researchers identified differences in characteristics between veteran cancer survivors and civilian cancer survivors.17 In addition to increased exposure risks, the veteran cancer survivor population is older than the general cancer survivorship population and is mostly male.17 Veterans’ comorbid conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, Parkinson disease, and peripheral neuropathy, which may be service related, complicate survivorship.17 These characteristics (age, gender, exposure risks, and comorbid conditions) influence the type of cancer diagnosed and treatment options, and they may ultimately impact survivorship needs

(Table 1).

The prevalence of mental health issues in the veteran population is significant.18 Posttraumatic stress disorder affects 7% to 8% of the general population at some point during their lifetime and as many as 16% of those returning from military deployment.19 In a predominantly

male veteran study correlating combat PTSD with cancerrelated PTSD, about half the participants (n = 170) met PTSD Criterion A, viewing their cancer as a traumatic experience.20 Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, and addictive disease all must be addressed in the survivorship plan of care.

Poor mental health has been linked to increased morbidity and mortality and can limit the veteran’s ability to participate in health promotion and medical care.21 Distress related to cancer is well recognized in the civilian population.22,23 Veterans are at risk for moderate-tosevere disabling distress, especially when the cancer is associated with their military service. Vietnam veterans who have a diagnosis of cancer report that they have already served their time and are now serving it again, having to wage a battle on cancer and undergo difficult treatments and associated adverse effects (AEs).24 It is important to note, however, that some veterans have developed strong coping skills, which gives them strength and resilience for the survivorship experience.25

Other factors also contribute to veterans’ unique survivorship needs. Many veterans have limited social and/or economic resources, making it difficult to receive cancer treatment and follow recommendations for a healthful lifestyle as a cancer survivor. Demographics from the VA have illustrated that many veterans have a limited support system (65% do not have a spouse), and many have low incomes.26 Although veterans comprise about 11% of the general population, they make up 26% of the homeless population.26 It is estimated that 260,000 veterans are homeless at some time during the course of a year, and of these, 45% have mental health issues and 70% have substance abuse problems.27 Basic needs such as housing, running water, heat and electricity, and nutrition must be met in order to prevent infection during treatment, maximize the benefit, and reduce the risks associated with treatment. Transportation issues can make it challenging to travel to medical centers for cancer surveillance following treatment.

Models of Care

As defined in the aforementioned IOM report, multiple models of survivorship care have surfaced over the years.6 Much that was originally seen and implemented in adult cancer survivorship was known from pediatric cancer care. Early models that surfaced included shared care models, nurse-led models, and tertiary survivorship clinics. Each model has its strengths and disadvantages.

The shared care model of survivorship involves a sharing of the responsibility for the survivor among different specialties, potentially at different facilities, and the primary care team. Typically, the PCP refers the patient to the oncologist when cancer is suspected or diagnosed. The primary care team continues to provide routine health maintenance and manages other health problems while the oncology team provides cancer care. The patient is transitioned back to the primary care team with a survivorship care plan (SCP) at 1 to 2 years after completion of cancer therapy or at the discretion of the oncology team.28 For

this model to work, the PCP must be willing to take on this responsibility, and there must be a coordinated effort for seamless communication between teams, which can be potentially challenging.

Nurse-led programs emerged in the pediatric populations. Pediatric nurse-led clinics assume care of the patient after active treatment to manage long-term AEs of cancer treatments, symptom management, care planning, and education. A comprehensive review of the literature identified that “nurse-led follow-up services are acceptable, appropriate, and effective.”6 Barriers to this model of care include a shortage of trained oncology nurses and a preference for physician follow-up by some cancer survivors who want the security of their oncologist for ongoing, long-term care.6

Survivorship follow-up clinics, a tertiary model of care, have been implemented at some larger academic centers. These clinics focus on cancer survivorship and are often separate from other routine health care visits. Typically, these clinics include multiple specialties and are often disease-specific. These types of clinics pose a different set of challenges regarding duplication of services and reimbursement issues.

As of yet, no model has been proven more effective than the others. Each institution and patient population may not lend themselves to a one-size-fits-all model. There may be different models of care needed, based on patient population. Regardless of the model selected, individualized survivorship care plans are an essential component of quality cancer survivorship care.

Addessing Survivorship Care

In 2009, 5 interdisciplinary leaders in VA cancer care (Ellen Ballard, RN; David Haggstrom, MD, MAS; Veronica Reis, PhD; Mark Detzer, PhD; and Tina Gill, MA) attended a breakout session on psychosocial oncology at the Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and most members of this team participated in the 2009-2012 VHA Cancer Care Collaboratives to improve the timeliness and quality of care for veterans who were cancer patients. Dr. Haggstrom and Ms. Ballard developed a SharePoint site for the Survivorship Special Interest Group (SIG) members through the Loma Linda VAMC in California. The SIG workgroup then built the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit, composed of

5 critical tools (Figure).

In July 2012, the VA Cancer Survivorship Toolkit content was disseminated at AVAHO and launched behind the VA firewall. It subsequently received accolades from the national program director for VHA Oncology and was listed on the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) Best Practices website. The toolkit is accessible to all VA programs, and suggestions for new content can be submitted directly on the site (Figure).

The development of a SCP began in late 2011 when SIG members collected examples of SCPs from leading organizations. The members compared this content with the IOM recommendations for SCPs and developed a template. The template was programmed for the VHA computerized patient record system (CPRS) and placed on the internal VA toolkit website. The template included the treatment summary and care plan. The treatment summary portion included the diagnosis and tumor characteristics, diagnostic tests used, dates and types of treatment, chemoprevention or maintenance treatments, supportive services required, the surveillance plan, and signs of recurrence. The care plan portion provided information on the likely course of recovery and a checklist for common long-term AEs in the areas of psychological distress, financial and practical effects, and physical effects. Also included was information about referral, health behaviors, late effects that may develop, contact information, and general resource information.

The computer applications coordinator at any VA can download the template from the toolkit onto their CPRS, and the template can then be brought into any progress note. Individual sites may also edit the template to suit specific needs. The SCP can be completed by any clinician with the appropriate clinical competencies. To date, > 50 sites have downloaded the SCP template for use.

Cancer Survivorship Clinic

At the Louis Stokes Cleveland (LSC) VAMC, a nurse-led model of a cancer survivorship clinic was established with an expert nurse practitioner (NP). A major catalyst for the development of this clinic was the receipt of a Specialty Care Education Center of Excellence, funded by the Offices of Specialty Care and Academic Affiliations. A priority of this project was the implementation of survivorship care for every veteran with a cancer diagnosis. A system redesign was implemented to deliver quality, cost-effective, patient-centered cancer care within an interprofessional, team-based practice. This clinic is imbedded within an interdisciplinary clinic setting where the NP works in close collaboration with the medical and surgical oncologists as well as providers from mental health, social work, nutrition, physical therapy, and others.

The first patients to receive survivorship care in this new model from the time of their diagnosis were veterans with breast cancer, sarcoma, melanoma, and lymphomas. Veterans are followed jointly by the NP and the medical and surgical oncologists during active treatment. The NP provides physical symptom assessment and management for patients both during and after treatment.

At the end of active treatment, patient visits are alternated between oncology physicians and the survivorship NP for 5 years. The timeline for follow-up visits is based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for each cancer type but then individualized based on patient need.29 During this 5-year time period, patients under active surveillance whose conditions have been stable are seen by the NP. Any concerning symptoms are immediately relayed to the primary oncologist or surgical oncologist, often the same day, and patients can be seen the same day if necessary, to improve coordination and access to services.

A unique focus of the clinic is the integration of health promotion and risk reduction that coincides with the active surveillance plan. This transition of active surveillance patients to the NP-led survivorship clinic not only opens access to newly diagnosed cancer patients to be seen by the oncologist, but also allows for seamless transition and coordination to active surveillance. Within the clinic structure, patients receive patient navigation beginning with a cancer concern; patients also receive screening for psychosocial distress at the time of diagnosis and at every visit. Patient navigation and distress screening are both considered essential elements to survivorship care in the most recent CoC guidelines.30 The survivorship NP keeps the primary care team up-to-date regarding patient care across the disease trajectory by alerting them to updates electronically in the CPRS in real time.

Survivorship Care Plan

A focus of the clinic has also been on the implementation of a formal SCP to be completed 3 months after the conclusion of active treatment. The formal SCP was downloaded from the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit and is composed of a 3-part summary. The 3 parts consist of the treatment summary, the plan for rehabilitation, and the plan for the future. The first section of the SCP is completed by the medical oncologist as a summary of treatment received by the veteran. The summary of treatment section is reviewed and discussed with the veteran survivor at the visit, and the second and third sections are completed during the 3-month follow-up visit with the veteran.

Success and Areas for Improvement

The survivorship clinic has been well received by veterans. Patient satisfaction scores have been overwhelmingly positive. Veterans appreciate and feel comfortable knowing their providers from the beginning of diagnosis along the entire disease trajectory. They know that if problems arise, the survivorship NP has direct access to the medical or surgical oncologist for immediate review.

The difficult challenge for the cancer care providers is to know when is the right time to transition care back to the PCP. Transitions of care often come with high anxiety and a sense of loss for the veteran. The 5-year survival mark is not always the appropriate transition time for some veterans. Those with extensive physical and mental health issues may need continuity of care and continued support from the oncology team.

The SCP has presented challenges in terms of when to complete and who should complete the form. There has also been concern over the length of the summary, how long it will take to complete the document, and which summary template to use. Areas for improvement with the template could potentially be to automate population of the chemotherapy and radiation summaries. Some software packages are available, but they are costly. Another issue with external software is getting it accepted by VHA and incorporated into the CPRS.

Recommendations

Many cancer programs are struggling to provide highquality survivorship care. The CoC, recognizing the challenges programs are having implementing survivorship care, has extended the accreditation requirement for full implementation from 2015 to 2019.31

The following recommendations should be considered for the successful implementation of a new survivorship program:

- Collect information from multiple resources to guide the establishment of the survivorship clinic;

- Become familiar with the IOM From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition;6

- Understand local issues and barriers specific to your care delivery system;

- Collaborate with key stakeholders from multiple specialties to gain momentum and buy-in;

- Hold regular meetings with stakeholders as well as leadership to identify and remove barriers to the clinic success;

- Join the VA Survivorship SIG to collaborate with other sites who have already started to pilot survivorship programs and discuss barriers to and successes of programs so as to not reinvent the wheel;

- Utilize the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit;

- Download the SCP;

- Establish a close partnership with your local cancer committee; and

- Collect and report data to show effectiveness and need.

All these strategies were vital to the success of the LSCVAMC survivorship program.

Summary

The VA is uniquely positioned to be a leader in highquality, comprehensive, and veteran-centered cancer survivorship care in the years ahead. The close relationship between specialty and primary care allows for smooth continuity of care and easy transitions between oncology and primary care. The comprehensive CPRS allows easy accessibility to information for the entire health care team. The Cancer Survivorship Toolkit provides a template of the survivorship care plan for the veteran and his or her health care providers.

The LSCVAMC is one of many VA institutions implementing quality care for cancer survivors and can serve as a role model for other VA programs initiating the survivorship care process (Table 2).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2014.

2. Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Levit LA, Balough EP, Nass SJ, Ganz PA, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

3. Stricker CT, O’Brien M. Implementing the commission on cancer standards for survivorship care plans. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;(suppl 18):15-22.

4. Cowens-Alvarado R, Sharpe K, Pratt-Chapman M, et al. Advancing survivorship care through the National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center: Developing American Cancer Society guidelines for primary care providers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(3):147-150.

5. Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2489-2495.

6. Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006.

7. Clark EJ, Stovall EL, Leigh S, Siu AL, Austin DK, Rowland JH, eds. Imperatives for Quality Cancer Care: Access, Advocacy, Action, and Accountability. Silver Spring, MD: National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship; 1996.

8. National Cancer Institute. Survivorship. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms Website. http://www.cancer.gov/dictionary?CdrID=445089. Accessed December 3, 2014.

9. Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220-241.

10. Moye J, Schuster JL, Latini DM, Naik AD. The future of cancer survivorship care for veterans. Fed Pract. 2010;27(3):36-43.

11. Naik AD, Martin LA, Karel M, et al. Cancer survivor rehabilitation and recovery: Protocol for the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vet-CaRes). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:93.

12. Beehler GP, Rodriques AE, Kay MA, Kiviniemi MT, Steinbrenner L. Lasting impact: Understanding the psychosocial implications of cancer among military veterans. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013:31(4):430-450.

13. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ diseases associated with Agent Orange. Public Health Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/agentorange/conditions/index.asp. Updated December 30, 2013. Accessed December3, 2014.

14. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Radiation. Public Health Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/radiation/index.asp. Updated December 31, 2013. Accessed December 3, 2014.

15. Cohen BE, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Kim S, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA non-mental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

16. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Gulf War veterans’ illnesses. Public Health Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/gulfwar/index.asp. Updated November 7, 2014. Accessed December 3, 2014.

17. National Cancer Institute. Cancer query systems. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Website. http://seer.cancer.gov/canques/index.html. Accessed December 3, 2014.

18. Suicide in the military: Army-NIH funded study points to risk and protective factors [news release]. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; March 3, 2014. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2014/suicide-in-the-military-army-nih-funded-study-points-to-risk-and-protective-factors.shtml. Accessed December 3, 2014.

19. Gates MA, Holowka DW, Vasterling JJ, Keane TM, Marx BP, Rosen RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans and military personnel: Epidemiology, screening, and case recognition. Psychol Serv. 2012;9(4):361-382.

20. Mulligan EA, Schuster Wachen J, Naik AD, Gosian J, Moye J. Cancer as a criterion a traumatic stressor for veterans: Prevalence and correlates. Psychol Trauma. 2014;6(suppl 1):S73-S81.

21. Musuuza JS, Sherman ME, Knudsen KJ, Sweeney HA, Tyler CV, Koroukian SM. Analyzing excess mortality from cancer among individuals with mental illness. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2469-2476.

22. Zabora J, Macmurray L. The history of psychosocial screening among cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013:30(6):625-635.

23. Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. Distress management: Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010:8(4):448-485.

24. Grassman DL. The Hero Within. St. Petersburg, FL: Vandamere Press; 2012.

25. Jahn AL, Herman L, Schuster J, Naik A, Moye J. Distress and resilience after cancer

in veterans. Res Hum Dev. 2012;9(3):229-247.

26. National Association of Social Workers. Social workers speak on veterans issues June 2009. National Association of Social Workers Website. http://www.naswdc.org/pressroom/2009/Social%20Work%20Veterans%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2014.

27. Homeless. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.va.gov/homeless. Accessed December 3, 2014.

28. Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117-5124.

29. NCCN Guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Website. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#site. Accessed December 3, 2014.

30. American College of Surgeons, Commission on Cancer. Cancer program standards 2012, version 1.2.1: Ensuring patient-centered care. https://www.facs.org/~/media/file/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx. Published January 21, 2014. Accessed December 3, 2014.

31. Accreditation committee clarifications for standard 3.3 survivorship care plan. American College of Surgeons Website. https://www.facs.org/publications/newsletters/coc-source/special-source/standard33. Published September 9, 2014. Accessed December 3, 2014.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2014.

2. Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Levit LA, Balough EP, Nass SJ, Ganz PA, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

3. Stricker CT, O’Brien M. Implementing the commission on cancer standards for survivorship care plans. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;(suppl 18):15-22.

4. Cowens-Alvarado R, Sharpe K, Pratt-Chapman M, et al. Advancing survivorship care through the National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center: Developing American Cancer Society guidelines for primary care providers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(3):147-150.

5. Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2489-2495.

6. Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006.

7. Clark EJ, Stovall EL, Leigh S, Siu AL, Austin DK, Rowland JH, eds. Imperatives for Quality Cancer Care: Access, Advocacy, Action, and Accountability. Silver Spring, MD: National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship; 1996.

8. National Cancer Institute. Survivorship. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms Website. http://www.cancer.gov/dictionary?CdrID=445089. Accessed December 3, 2014.

9. Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220-241.

10. Moye J, Schuster JL, Latini DM, Naik AD. The future of cancer survivorship care for veterans. Fed Pract. 2010;27(3):36-43.

11. Naik AD, Martin LA, Karel M, et al. Cancer survivor rehabilitation and recovery: Protocol for the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vet-CaRes). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:93.

12. Beehler GP, Rodriques AE, Kay MA, Kiviniemi MT, Steinbrenner L. Lasting impact: Understanding the psychosocial implications of cancer among military veterans. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013:31(4):430-450.

13. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ diseases associated with Agent Orange. Public Health Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/agentorange/conditions/index.asp. Updated December 30, 2013. Accessed December3, 2014.

14. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Radiation. Public Health Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/radiation/index.asp. Updated December 31, 2013. Accessed December 3, 2014.

15. Cohen BE, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Kim S, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA non-mental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24.

16. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Gulf War veterans’ illnesses. Public Health Website. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/gulfwar/index.asp. Updated November 7, 2014. Accessed December 3, 2014.

17. National Cancer Institute. Cancer query systems. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Website. http://seer.cancer.gov/canques/index.html. Accessed December 3, 2014.

18. Suicide in the military: Army-NIH funded study points to risk and protective factors [news release]. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; March 3, 2014. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2014/suicide-in-the-military-army-nih-funded-study-points-to-risk-and-protective-factors.shtml. Accessed December 3, 2014.

19. Gates MA, Holowka DW, Vasterling JJ, Keane TM, Marx BP, Rosen RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans and military personnel: Epidemiology, screening, and case recognition. Psychol Serv. 2012;9(4):361-382.

20. Mulligan EA, Schuster Wachen J, Naik AD, Gosian J, Moye J. Cancer as a criterion a traumatic stressor for veterans: Prevalence and correlates. Psychol Trauma. 2014;6(suppl 1):S73-S81.

21. Musuuza JS, Sherman ME, Knudsen KJ, Sweeney HA, Tyler CV, Koroukian SM. Analyzing excess mortality from cancer among individuals with mental illness. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2469-2476.

22. Zabora J, Macmurray L. The history of psychosocial screening among cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013:30(6):625-635.

23. Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. Distress management: Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010:8(4):448-485.

24. Grassman DL. The Hero Within. St. Petersburg, FL: Vandamere Press; 2012.

25. Jahn AL, Herman L, Schuster J, Naik A, Moye J. Distress and resilience after cancer

in veterans. Res Hum Dev. 2012;9(3):229-247.

26. National Association of Social Workers. Social workers speak on veterans issues June 2009. National Association of Social Workers Website. http://www.naswdc.org/pressroom/2009/Social%20Work%20Veterans%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2014.

27. Homeless. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.va.gov/homeless. Accessed December 3, 2014.

28. Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117-5124.

29. NCCN Guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Website. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#site. Accessed December 3, 2014.

30. American College of Surgeons, Commission on Cancer. Cancer program standards 2012, version 1.2.1: Ensuring patient-centered care. https://www.facs.org/~/media/file/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx. Published January 21, 2014. Accessed December 3, 2014.