User login

The best way to deal with the recent resurgence in West Nile virus is to emphasize prevention.

West Nile virus (WNV) is back with a vengeance this year. As of Sept. 4, 2012, there were 1,993 reported cases of WNV disease in people, including 1,069 with neuroinvasive disease and 87 deaths. My state, Texas, is leading the pack with a total of 888 cases, 443 neuroinvasive disease cases, and 35 deaths. Texas’ West Nile problem is clearly the worst in the country. The next-highest number of total cases is only 119, in South Dakota.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the total of 1,993 cases is the highest number of WNV disease cases reported to the CDC through the first week in September since the virus was first detected in the United States in 1999. It’s not clear why this resurgence is happening now, or why Texas has been so hard hit. Some say that rising temperatures have resulted in an increased mosquito population, but here in Texas there is also a drought and mosquitos need moisture, so I’m not sure about that.

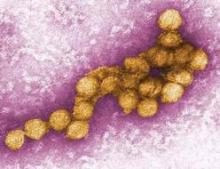

An arbovirus, WNV is usually transmitted to humans after a bite from an infected Culex mosquito. The transmission cycle is maintained between mosquito and vertebrate hosts, usually birds. Humans are actually an incidental and dead-end host. Though rare, person-to-person transmission has been documented through both blood transfusion and solid organ transplantation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2196-203).

When speaking with your patients, it’s worth reemphasizing the methods for prevention. Parents should be instructed to apply one of the Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents to their children before they go outside, using just enough to protect exposed skin. Products containing up to 30% DEET – but not higher – can be used in children older than 2 months of age. Products containing both DEET and a sunscreen should be avoided, since sunscreen needs to be applied more frequently.

Children should be covered up with clothing as much as possible when outside, and netting should be used over infant carriers. Outdoor exposure should be limited at dusk and dawn, when mosquitos are most active. Holes in screen doors should be repaired. Standing water, which attracts mosquitos, is a major hazard and should be avoided. Birdba ths and blow-up pools need to be emptied out often, and children should steer clear of puddles.

Here in Texas, the state health department has issued a statement preparing people for aerial spraying of chemicals to control the mosquitos. Each state most likely will develop its own recommendations, which should be available on the state health department website.

Routine screening of the U.S. blood supply was initiated in 2003, and no cases have been identified in donated blood since then. A single case of congenital infection also has been reported (MMWR 2002;51:1135-6). There are specific management guidelines for mother, fetus, and newborn if women are diagnosed with WNV during pregnancy (MMWR 2004;53:154-7).

Most people who become infected with WNV will be asymptomatic. About 1 in 5 who are infected will develop symptoms such as fever, headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash after a 2-14 day incubation period. Less than 1% will develop neuroinvasive disease, but of those who do, about 10% are fatal.

It’s important to include WNV in your differential diagnosis for children who present with a febrile illness, meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis, particularly if they’ve had exposure to mosquitos during the summer and early fall in endemic areas. The clinical presentation of neuroinvasive WNV is indistinguishable from those of other causes of viral meningitis and/or encephalitis. While the epidemiological characteristics of WNV disease in children are similar to those in adults, neuroinvasive disease due to WNV is more likely to manifest as meningitis in children than in older adults, who are more likely to develop encephalitis (Pediatrics 2009;123:e1084-9).

Because there is no specific treatment for WNV, and the majority of patients have a self-limited course, the diagnosis need not be made in every febrile patient. A definitive diagnosis should be sought in individuals with fever and acute neurologic symptoms who have recently been exposed to mosquitos, are solid organ transplant recipients, or are pregnant.

The presence of WNV-reactive IgM antibody in serum or cerebrospinal fluid supports a recent infection. However, anti-WNV IgM can persist up to a year in some people, so its presence may represent a prior infection. Moreover, if serum is tested within the first 10 days of illness, IgM antibody may not always be detected. Convalescent titers should be obtained 2-3 weeks following the onset of illness.

Treatment is supportive care. Standard precautions are recommended for hospitalized patients in the American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book on pages 792-5 (Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. L.K. Pickering, Ed. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics). Most people will recover from even the neuroinvasive manifestations of WNV, although symptoms may last for several weeks and those with severe cases may require hospitalization for supportive treatment. Serious sequelae can occur among those with underlying immune deficiencies.

For the most up-to-date information on WNV statistics from the CDC, click here.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at pdnews@elsevier.com.

The best way to deal with the recent resurgence in West Nile virus is to emphasize prevention.

West Nile virus (WNV) is back with a vengeance this year. As of Sept. 4, 2012, there were 1,993 reported cases of WNV disease in people, including 1,069 with neuroinvasive disease and 87 deaths. My state, Texas, is leading the pack with a total of 888 cases, 443 neuroinvasive disease cases, and 35 deaths. Texas’ West Nile problem is clearly the worst in the country. The next-highest number of total cases is only 119, in South Dakota.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the total of 1,993 cases is the highest number of WNV disease cases reported to the CDC through the first week in September since the virus was first detected in the United States in 1999. It’s not clear why this resurgence is happening now, or why Texas has been so hard hit. Some say that rising temperatures have resulted in an increased mosquito population, but here in Texas there is also a drought and mosquitos need moisture, so I’m not sure about that.

An arbovirus, WNV is usually transmitted to humans after a bite from an infected Culex mosquito. The transmission cycle is maintained between mosquito and vertebrate hosts, usually birds. Humans are actually an incidental and dead-end host. Though rare, person-to-person transmission has been documented through both blood transfusion and solid organ transplantation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2196-203).

When speaking with your patients, it’s worth reemphasizing the methods for prevention. Parents should be instructed to apply one of the Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents to their children before they go outside, using just enough to protect exposed skin. Products containing up to 30% DEET – but not higher – can be used in children older than 2 months of age. Products containing both DEET and a sunscreen should be avoided, since sunscreen needs to be applied more frequently.

Children should be covered up with clothing as much as possible when outside, and netting should be used over infant carriers. Outdoor exposure should be limited at dusk and dawn, when mosquitos are most active. Holes in screen doors should be repaired. Standing water, which attracts mosquitos, is a major hazard and should be avoided. Birdba ths and blow-up pools need to be emptied out often, and children should steer clear of puddles.

Here in Texas, the state health department has issued a statement preparing people for aerial spraying of chemicals to control the mosquitos. Each state most likely will develop its own recommendations, which should be available on the state health department website.

Routine screening of the U.S. blood supply was initiated in 2003, and no cases have been identified in donated blood since then. A single case of congenital infection also has been reported (MMWR 2002;51:1135-6). There are specific management guidelines for mother, fetus, and newborn if women are diagnosed with WNV during pregnancy (MMWR 2004;53:154-7).

Most people who become infected with WNV will be asymptomatic. About 1 in 5 who are infected will develop symptoms such as fever, headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash after a 2-14 day incubation period. Less than 1% will develop neuroinvasive disease, but of those who do, about 10% are fatal.

It’s important to include WNV in your differential diagnosis for children who present with a febrile illness, meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis, particularly if they’ve had exposure to mosquitos during the summer and early fall in endemic areas. The clinical presentation of neuroinvasive WNV is indistinguishable from those of other causes of viral meningitis and/or encephalitis. While the epidemiological characteristics of WNV disease in children are similar to those in adults, neuroinvasive disease due to WNV is more likely to manifest as meningitis in children than in older adults, who are more likely to develop encephalitis (Pediatrics 2009;123:e1084-9).

Because there is no specific treatment for WNV, and the majority of patients have a self-limited course, the diagnosis need not be made in every febrile patient. A definitive diagnosis should be sought in individuals with fever and acute neurologic symptoms who have recently been exposed to mosquitos, are solid organ transplant recipients, or are pregnant.

The presence of WNV-reactive IgM antibody in serum or cerebrospinal fluid supports a recent infection. However, anti-WNV IgM can persist up to a year in some people, so its presence may represent a prior infection. Moreover, if serum is tested within the first 10 days of illness, IgM antibody may not always be detected. Convalescent titers should be obtained 2-3 weeks following the onset of illness.

Treatment is supportive care. Standard precautions are recommended for hospitalized patients in the American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book on pages 792-5 (Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. L.K. Pickering, Ed. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics). Most people will recover from even the neuroinvasive manifestations of WNV, although symptoms may last for several weeks and those with severe cases may require hospitalization for supportive treatment. Serious sequelae can occur among those with underlying immune deficiencies.

For the most up-to-date information on WNV statistics from the CDC, click here.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at pdnews@elsevier.com.

The best way to deal with the recent resurgence in West Nile virus is to emphasize prevention.

West Nile virus (WNV) is back with a vengeance this year. As of Sept. 4, 2012, there were 1,993 reported cases of WNV disease in people, including 1,069 with neuroinvasive disease and 87 deaths. My state, Texas, is leading the pack with a total of 888 cases, 443 neuroinvasive disease cases, and 35 deaths. Texas’ West Nile problem is clearly the worst in the country. The next-highest number of total cases is only 119, in South Dakota.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the total of 1,993 cases is the highest number of WNV disease cases reported to the CDC through the first week in September since the virus was first detected in the United States in 1999. It’s not clear why this resurgence is happening now, or why Texas has been so hard hit. Some say that rising temperatures have resulted in an increased mosquito population, but here in Texas there is also a drought and mosquitos need moisture, so I’m not sure about that.

An arbovirus, WNV is usually transmitted to humans after a bite from an infected Culex mosquito. The transmission cycle is maintained between mosquito and vertebrate hosts, usually birds. Humans are actually an incidental and dead-end host. Though rare, person-to-person transmission has been documented through both blood transfusion and solid organ transplantation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2196-203).

When speaking with your patients, it’s worth reemphasizing the methods for prevention. Parents should be instructed to apply one of the Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents to their children before they go outside, using just enough to protect exposed skin. Products containing up to 30% DEET – but not higher – can be used in children older than 2 months of age. Products containing both DEET and a sunscreen should be avoided, since sunscreen needs to be applied more frequently.

Children should be covered up with clothing as much as possible when outside, and netting should be used over infant carriers. Outdoor exposure should be limited at dusk and dawn, when mosquitos are most active. Holes in screen doors should be repaired. Standing water, which attracts mosquitos, is a major hazard and should be avoided. Birdba ths and blow-up pools need to be emptied out often, and children should steer clear of puddles.

Here in Texas, the state health department has issued a statement preparing people for aerial spraying of chemicals to control the mosquitos. Each state most likely will develop its own recommendations, which should be available on the state health department website.

Routine screening of the U.S. blood supply was initiated in 2003, and no cases have been identified in donated blood since then. A single case of congenital infection also has been reported (MMWR 2002;51:1135-6). There are specific management guidelines for mother, fetus, and newborn if women are diagnosed with WNV during pregnancy (MMWR 2004;53:154-7).

Most people who become infected with WNV will be asymptomatic. About 1 in 5 who are infected will develop symptoms such as fever, headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash after a 2-14 day incubation period. Less than 1% will develop neuroinvasive disease, but of those who do, about 10% are fatal.

It’s important to include WNV in your differential diagnosis for children who present with a febrile illness, meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis, particularly if they’ve had exposure to mosquitos during the summer and early fall in endemic areas. The clinical presentation of neuroinvasive WNV is indistinguishable from those of other causes of viral meningitis and/or encephalitis. While the epidemiological characteristics of WNV disease in children are similar to those in adults, neuroinvasive disease due to WNV is more likely to manifest as meningitis in children than in older adults, who are more likely to develop encephalitis (Pediatrics 2009;123:e1084-9).

Because there is no specific treatment for WNV, and the majority of patients have a self-limited course, the diagnosis need not be made in every febrile patient. A definitive diagnosis should be sought in individuals with fever and acute neurologic symptoms who have recently been exposed to mosquitos, are solid organ transplant recipients, or are pregnant.

The presence of WNV-reactive IgM antibody in serum or cerebrospinal fluid supports a recent infection. However, anti-WNV IgM can persist up to a year in some people, so its presence may represent a prior infection. Moreover, if serum is tested within the first 10 days of illness, IgM antibody may not always be detected. Convalescent titers should be obtained 2-3 weeks following the onset of illness.

Treatment is supportive care. Standard precautions are recommended for hospitalized patients in the American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book on pages 792-5 (Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. L.K. Pickering, Ed. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics). Most people will recover from even the neuroinvasive manifestations of WNV, although symptoms may last for several weeks and those with severe cases may require hospitalization for supportive treatment. Serious sequelae can occur among those with underlying immune deficiencies.

For the most up-to-date information on WNV statistics from the CDC, click here.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at pdnews@elsevier.com.