User login

Nearly one in every six women will experience chronic vulvar symptoms at some point, from ongoing itching to sensations of rawness, burning, or dyspareunia. Regrettably, clinicians generally are taught only a few possible causes for these symptoms, primarily infections such as yeast, bacterial vaginosis, herpes simplex virus, or anogenital warts. However, infections rarely produce chronic symptoms that do not respond, at least temporarily, to therapy.

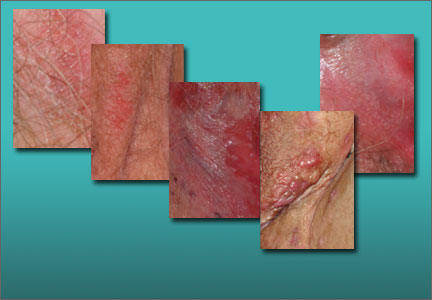

In this two-part series, we focus on a total of 10 cases of vulvar symptoms, zeroing in on diagnosis and treatment. In this first part, we describe five patient scenarios illustrating the diagnosis and treatment of:

- lichen sclerosus

- vulvodynia

- lichen simplex chronicus

- lichen planus

- hidradenitis suppurativa.

In many chronic cases, more than one entity is the cause

Specific skin diseases, sensations of rawness from various external and internal irritants, neuropathy, and psychological issues are all much more common causes of chronic vulvar symptoms than infection. Moreover, most women with chronic vulvar symptoms have more than one entity producing their discomfort.

Very often, the cause of a patient’s symptoms is not clear at the first visit, with nonspecific redness or even normal skin seen on examination. Pathognomonic skin findings can be obscured by irritant contact dermatitis caused by unnecessary medications or overwashing, atrophic vaginitis, and/or rubbing and scratching. In such cases, obvious abnormalities must be eliminated and the patient reevaluated to definitively discover and treat the cause of the symptoms.

CASE 1. ANOGENITAL ITCHING AND DYSPAREUNIA

A 62-year-old woman schedules a visit to address her anogenital itching. She reports pain with scratching and has developed introital dyspareunia. On physical examination, you find a well-demarcated white plaque of thickened, crinkled skin (FIGURE 1). A wet mount shows parabasal cells and no lactobacilli.

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus and atrophic vagina.

Treatment: Halobetasol ointment, an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid, once or twice daily; along with estradiol cream (0.5 g intravaginally) 3 times a week.

Lichen sclerosus is a skin disease found most often on the vulva of postmenopausal women, although it also can affect prepubertal children and reproductive-age women. Lichen sclerosus is multifactorial in pathogenesis, including prominent autoimmune factors, local environmental factors, and genetic predisposition.1

Although there is no cure for lichen sclerosus, the symptoms and clinical abnormalities usually can be well managed with ultra-potent topical corticosteroids. However, scarring and architectural changes are not reversible. Moreover, poorly controlled lichen sclerosus exhibits malignant transformation on anogenital skin in about 3% of affected patients.

The standard of care is application of an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid ointment once or twice daily until the skin texture normalizes again. The most common of such corticosteroids are clobetasol, halobetasol, and betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle (betamethasone dipropionate in the usual vehicle is only a medium-high medication in terms of potency.) One of us (L.E.) finds that some women experience irritation with generic clobetasol.

The ointment form of the selected corticosteroid is preferred, as creams are irritating to the vulva in most women because they contain more alcohols and preservatives than ointments do. The amount to be used is very small—far smaller than the pea-sized amount often suggested. By using this smaller amount, we avoid spread to the surrounding hair-bearing skin, which is at greater risk for steroid dermatitis and atrophy than the modified mucous membranes.

Related video: Lichen sclerosis: My approach to treatment Michael Baggish, MD

Even asymptomatic lichen sclerosus can progress

Most vulvologists agree that when the skin normalizes (not when symptoms subside), it is best to either decrease the frequency of application of the ultra-potent corticosteroid to two or three times a week, or to continue daily use with a lower-potency corticosteroid such as triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. Discontinuation of therapy usually results in recurrence.2

Treatment should not be based solely on symptoms, as asymptomatic lichen sclerosus can progress and cause permanent scarring and an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.

Although no studies have shown a decreased risk for squamous cell carcinoma with ongoing use of a corticosteroid, vulvologists have observed that malignant transformation occurs uniformly in the setting of poorly controlled lichen sclerosus. Immune dysregulation and inflammation may play an important role, so careful management to minimize inflammation may help prevent a malignancy.3

Secondary treatment choices

Secondary choices for lichen sclerosus include the topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel) but not testosterone, which has been shown to be ineffective. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are useful but often burn upon application, and they are “black-boxed” for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma. Therefore, although squamous cell carcinoma associated with their use is extraordinarily uncommon, patients should be advised of these risks, particularly because lichen sclerosus already exhibits this association.

Most postmenopausal women with lichen sclerosus also exhibit hypothyroidism, so they should be monitored for this. However, thyroid function testing in 18 children showed no evidence of hypothyroidism in that age group (L.E. unpublished data).

Estrogen replacement may be advised

Postmenopausal women who have prominent introital lichen sclerosus or dyspareunia should receive estrogen replacement of some type so that there is only one cause, rather than two, for their dyspareunia, thinning, fragility, and inelasticity.

Women with well-controlled lichen sclerosus should be followed twice a year to ensure that their disease remains suppressed with ongoing therapy, and to evaluate for active disease, adverse effects of therapy, and the appearance of dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma.

Women with lichen sclerosus occasionally experience discomfort after their clinical skin disease has cleared. These women now have developed vulvodynia triggered by their lichen sclerosus.

Related series: Vulvar Pain Syndromes—A 3-part roundtable

Part 1. Making the correct diagnosis (September 2011)

Part 2. A bounty of treatments—but not all of them proven (October 2011)

Part 3. Causes and treatment of vestibulodynia (November 2011)

CASE 2. IS IT REALLY CHRONIC YEAST INFECTION?

A 36-year-old woman consults you about her history of chronic yeast infection that manifests as introital burning, discharge, and dyspareunia. She is otherwise healthy, except for irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia.

Physical examination reveals a mild patchy redness of the vestibule and surrounding modified mucous membranes (FIGURE 2). Gentle probing with a cotton swab triggers exquisite pain in the vestibule, with slight extension to the labia minora. A wet mount shows no evidence of increased white blood cells, parabasal cells, clue cells, or yeast forms. Lactobacilli are abundant.

Diagnosis: Vulvodynia, with a nearly vestibulodynia pattern.

Treatment: Venlafaxine and pelvic floor physical therapy.

Vulvodynia is a genital pain syndrome defined as sensations of chronic burning, irritation, rawness, and soreness in the absence of objective disease and infection that could explain the discomfort. Vulvodynia occurs in approximately 7% to 8% of women.4

Vulvodynia generally is believed to be a multifactorial symptom, occurring as a result of pelvic floor dysfunction and neuropathic pain,5,6 with anxiety/depression issues exacerbating symptoms. Some recent studies have shown the presence of biochemical mediators of inflammation in the absence of clinical and histologic inflammation.7 Discomfort often is worsened by infections or the application of common irritants (creams, panty liners, soaps, some topical anesthetics). Estrogen deficiency is another common exacerbating factor.

Women tend to exhibit other pain syndromes such as chronic headaches, fibromyalgia, temperomandibular disorder, or premenstrual syndrome, as well as prominent anxiety, depression, sleep disorder, and so on.

Almost uniformly present are symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, such as constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis or urinary symptoms in the absence of a urinary tract infection. These women also are frequently unusually intolerant of medications.

Classifying vulvodynia

There are two primary patterns of vulvodynia. The first and most common is vestibulodynia, formerly called vulvar vestibulitis. The term vestibulitis was eliminated to reflect the absence of clinical and histologic inflammation. Vestibulodynia refers to pain that is always limited to the vestibule. Generalized vulvodynia, however, extends beyond the vestibule, is migratory, or does not include the vestibule.

Several vulvologists have found that many patients exhibit features of both types of vulvodynia, and these patterns probably exist on a spectrum. The difference is probably unimportant in clinical practice, except that vestibulodynia can be treated with vestibulectomy.

How we manage vulvodynia

We focus on pelvic floor physical therapy and on the provision of medication for neuropathic pain, which is initiated at very small doses and gradually increased to active doses.8 The medications used and the ultimate doses often required include:

- amitriptyline or desipramine 150 mg

- gabapentin 600 to 1,200 mg three times daily

- venlafaxine XR 150 mg daily

- pregabalin 150 mg twice a day

- duloxetine 60 mg a day.

Compounded amitriptyline 2% with baclofen 2% cream applied three times daily is beneficial for many patients, and topical lidocaine jelly 2% or ointment 5% (which often burns) can help provide immediate temporary relief.

Most patients require sex therapy and counseling for maximal improvement. Women with vestibulodynia in whom these therapies fail are good candidates for vestibulectomy if their pain is strictly limited to the vestibule. Fortunately, most women do not require this aggressive therapy.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; July 2013)

CASE 3. SEVERE ITCHING DISRUPTS SLEEP

A 34-year-old patient reports excruciating itching, with disruption of daily activities and sleep. She has been treated for candidiasis on multiple occasions, but in your office her wet mount and confirmatory culture are negative. Physical examination reveals a pink, lichenified plaque with excoriation (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Lichen simplex chronicus.

Treatment: Ultra-potent corticosteroid ointment applied very sparingly twice daily and covered with petroleum jelly. You also order nighttime sedation with amitriptyline to break the itch-scratch cycle. When the patient’s itching resolves and her skin clears, you taper her off the corticosteroid, warning her that recurrence is likely, and instruct her to restart the medication immediately should itching recur.

Lichen simplex chronicus (formerly called squamous hyperplasia or hyperplastic dystrophy, and also known as eczema, neurodermatitis, or localized atopic dermatitis) occurs when irritation from any cause produces itching in a predisposed person. The subsequent scratching and rubbing both produce the rash and exacerbate the irritation that drives the itching, even after the original cause is gone. The rubbing and scratching perpetuate the irritation and itching, producing the “itch-scratch” cycle.

The appearance of lichen simplex chronicus is produced by rubbing (where the skin thickens and lichenifies) or scratching (where the skin becomes red with linear erosions, called excoriations, caused by fingernails).

The initial trigger for lichen simplex chronicus often is an infection—often yeast—but overwashing, stress, sweat, heat, urine, irritating lubricants, and use of panty liners also may precipitate the itching. At the office visit, the original infection or other cause of irritation often is no longer present, and only lichen simplex chronicus can be identified.

How to treat lichen simplex chronicus

Management of lichen simplex chronicus requires very sparing application of an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid (clobetasol, halobetasol, or betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle ointment) twice daily, with the ointment covered with petroleum jelly. Care also must be taken to avoid irritants.

In addition, nighttime sedation helps to interrupt the itch-scratch cycle by preventing rubbing during sleep.

When the skin appears normal and itching has resolved, taper the medication down or off, warning the patient that recurrence is common with any future irritation.

Restart therapy immediately upon recurrence to prevent lichenification and chronic problems.

Second-line medications include calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus). Although these agents do not contribute to atrophy, they are less effective than topical corticosteroids,9 cost more, and can cause burning upon application.

Unlike lichen sclerosus, lichen simplex chronicus does not always recur upon cessation of treatment, and there is no need for concern about an increased risk of malignancy or significant scarring.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

CASE 4. ORAL AND VULVAR INVOLVEMENT

A 73-year-old patient seeks your help in alleviating longstanding introital itching and rawness, with dyspareunia. She has tried topical estradiol cream intravaginally three times weekly in combination with weekly fluconazole, to no avail.

Physical examination reveals deep red patches and erosions of the vestibule, with complete resorption of the labia minora (FIGURE 4). Patchy redness of the vagina is apparent as well, so you examine the patient’s mouth and find deep redness of the gingivae and erosions of the buccal mucosae, with surrounding white, lacy papules. A wet mount shows a marked increase in lymphocytes and parabasal cells, with a pH of more than 7.

Diagnosis: After correlating the vulvar and oral findings, you make a diagnosis of lichen planus.

Treatment: You initiate halobetasol ointment twice daily, to be applied to the vulva. You also continue vaginal estradiol cream but add hydrocortisone acetate 200 mg compounded vaginal suppositories nightly, as well as clobetasol gel to be applied to oral lesions three times a day. You follow the patient closely for secondary yeast of the mouth and vagina.

Erosive multimucosal lichen planus is a disease of cell-mediated immunity that overwhelmingly affects menopausal women. The most common surfaces involved are the mouth, vagina, rectal mucosa, and vulva; usually, at least two surfaces are affected. The esophagus, extra-auditory canals, nasal mucosa, and eyes also can be involved. Dry, extragenital skin usually is not affected in the setting of erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus.

Vulvar lichen planus most often is controlled with ultra-potent topical corticosteroids (again, clobetasol, halobetasol, or betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle), but other mucosal surfaces often are more difficult to manage. Although there is no definitive cure for this condition, careful local care, estrogen replacement, and suppression of oral and vulvovaginal candidiasis usually provide relief.

Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) sometimes are useful in patients who improve only partially after treatment with a topical corticosteroid, provided burning with application is tolerable.10 Systemic immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha blockers (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab), as well as oral retinoids, can be added for more recalcitrant disease.11

How to manage disease that affects the vagina

When the vagina is involved in lichen planus, treatment is important to prevent scarring, as well as rawness and pain from irritant contact dermatitis caused by purulent vaginal secretions. Occasionally, a 25-mg hydrocortisone acetate rectal suppository inserted into the vagina nightly improves vaginal lichen planus, but sometimes more potent suppositories, such as doses of 100 to 200 mg, may be compounded. Dilators should be inserted daily to prevent vaginal synechiae.

Oral involvement requires targeted treatment

The mouth is almost always involved in lichen planus. If a dermatologist is not involved in patient care, a prescription for dexamethasone/nystatin elixir (50:50) (5 mL swish, hold, and spit four times daily) can improve oral symptoms remarkably. Alternatively, clobetasol gel applied to affected areas of the mouth three or four times daily can be helpful. Secondary yeast of the vagina and mouth are common with the use of topical corticosteroids.

Careful clinical follow-up is advised

Like uncontrolled lichen sclerosus, erosive lichen planus of the vulva produces scarring and sometimes eventuates into squamous cell carcinoma. Therefore, careful clinical surveillance is warranted. And therapy must be continued to prevent recurrence of lichen planus (as it must be for lichen sclerosus), scarring, and to decrease the risk of squamous cell carcinoma. And like lichen sclerosus, lichen planus sometimes triggers vulvodynia.

CASE 5. MULTIPLE BOILS IN THE GROIN

A 31-year-old morbidly obese African American woman comes to your office with continually evolving boils in the groin. A culture shows Bacterioides spp, Escherichia coli, and Peptococcus spp. In the past, multiple courses of various antibiotics have provided only modest relief.

Physical examination reveals fluctuant nodules, scars, and draining sinus tracts of the hair-bearing vulva and crural crease (FIGURE 5). The axillae are clear.

Diagnosis: Hidradenitis suppurativa.

Treatment: The patient begins taking minocycline 100 mg twice daily. Because she is a smoker, you refer her to an aggressive primary care provider for smoking cessation and weight loss management.

Three months later, the patient is developing only about two nodules a month, managed by early intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is sometimes called inverse acne because the underlying pathogenesis is similar to cystic acne. Follicular plugging with keratin debris occurs, with additional keratin, sebaceous material, and normal skin bacteria trapped below the occlusion and distending the follicle. As the follicle wall stretches, thins, and allows for leakage of keratin debris into surrounding dermis, a brisk foreign-body response produces a noninfectious abscess.

Hidradenitis suppurativa affects more than 2% of the population.12 It appears only in areas of the body that contain apocrine glands and in individuals who have double- or triple-outlet follicles that predispose them to follicular occlusion. Therefore, this disease has a genetic component.

Other risk factors include male sex, African genetic background, obesity, and smoking. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome is significantly higher in individuals with hidradenitis suppurativa than in the general population.13

Recommended management

Treatments include:

- chronic antibiotics with nonspecific anti-inflammatory activity (tetracyclines, erythromycin, clindamycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole)

- intralesional injection of corticosteroids for early nodules (which often aborts their development)

- TNF alpha blockers (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab)14–16

- surgical removal of affected skin—the definitive therapy.

Note, however, that anogenital hidradenitis often is too extensive for surgery to be practical. In patients who have localized hidradenitis, primary excision is an excellent early therapy, provided the patient is advised that recurrence may occur in apocrine-containing nearby skin. Aggressive curettage of the roof of the cysts has been performed by some clinicians with good response.

Don’t overlook adjuvant approaches

Smoking cessation and weight loss often are useful.

Other therapies backed by anecdotal evidence include oral contraceptives or spironolactone for their anti-androgen effect, as well as metformin, a more recently studied agent.

Local care with antibacterial soaps and topical antibiotics may be useful for some women.

MORE CASES TO COME

In Part 2 of this series, which will appear in the June 2014 issue of OBG Management, we will discuss the following cases:

- atrophic vagina and atrophic vaginitis

- contact dermatitis

- vulvar aphthae

- desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

- psoriasis.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

- Doulaveri G, Armira K, Kouris A, et al. Genital vulvar lichen sclerosus in monozygotic twin women: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5(3):321–325.

- Virgili A, Minghetti S, Borghi A, Corazza M. Proactive maintenance therapy with a topical corticosteroid for vulvar lichen sclerosus: Preliminary results of a randomized study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(6):1316–1324.

- Brodrick B, Belkin ZR, Goldstein AT. Influence of treatments on prognosis for vulvar lichen sclerosus: Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(6):780–786.

- Harlow BL, Kunitz CG, Nguyen RH, Rydell SA, Turner RM, MacLehose RF. Prevalence of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of vulvodynia: Population-based estimates from two geographic regions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):40.e1–e8.

- Morin M, Bergeron S, Khalife S, Mayrand MH, Binik YM. Morphometry of the pelvic floor muscles in women with and without provoked vestibulodynia using 4D ultrasound. J Sex Med. 2014;11(3):776–785.

- Hampson JP, Reed BD, Clauw DJ, et al. Augmented central pain processing in vulvodynia. J Pain. 2013;14(6):579–589.

- Omoigui S. The biochemical origin of pain: the origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response. Part 2 of 3: Inflammatory profile of pain syndromes. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69(6):1169–1178.

- Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia guideline. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2005;9(1):40–51.

- Frankel HC, Qureshi AA. Comparative effectiveness of topical calcineurin inhibitors in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(2):113–123.

- Samycia M, Lin AN. Efficacy of topical calcineurin inhibitors in lichen planus. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16(4):221–229.

- Mirowski GW, Goddard A. Treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28(4):717–725.

- Vinding GR, Miller IM, Zarchi K, et al. The prevalence of inverse recurrent suppuration: A population-based study of possible hidradenitis suppurativa [published online ahead of print December 16, 2013]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.12787.

- Gold DA, Reeder VJ, Mahan MG, Hamzavi IH. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(4):699–703.

- Scheinfeld N. Hidradenitis suppurativa: A practical review of possible medical treatments based on over 350 hidradenitis patients. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(4):1.

- Kimball AB, Kerdel F, Adams D, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa:

A parallel randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(12):846–855. - Chinniah N, Cains GD. Moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa treated with biological therapies [published online ahead of print January 23, 2014]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.12136.

Nearly one in every six women will experience chronic vulvar symptoms at some point, from ongoing itching to sensations of rawness, burning, or dyspareunia. Regrettably, clinicians generally are taught only a few possible causes for these symptoms, primarily infections such as yeast, bacterial vaginosis, herpes simplex virus, or anogenital warts. However, infections rarely produce chronic symptoms that do not respond, at least temporarily, to therapy.

In this two-part series, we focus on a total of 10 cases of vulvar symptoms, zeroing in on diagnosis and treatment. In this first part, we describe five patient scenarios illustrating the diagnosis and treatment of:

- lichen sclerosus

- vulvodynia

- lichen simplex chronicus

- lichen planus

- hidradenitis suppurativa.

In many chronic cases, more than one entity is the cause

Specific skin diseases, sensations of rawness from various external and internal irritants, neuropathy, and psychological issues are all much more common causes of chronic vulvar symptoms than infection. Moreover, most women with chronic vulvar symptoms have more than one entity producing their discomfort.

Very often, the cause of a patient’s symptoms is not clear at the first visit, with nonspecific redness or even normal skin seen on examination. Pathognomonic skin findings can be obscured by irritant contact dermatitis caused by unnecessary medications or overwashing, atrophic vaginitis, and/or rubbing and scratching. In such cases, obvious abnormalities must be eliminated and the patient reevaluated to definitively discover and treat the cause of the symptoms.

CASE 1. ANOGENITAL ITCHING AND DYSPAREUNIA

A 62-year-old woman schedules a visit to address her anogenital itching. She reports pain with scratching and has developed introital dyspareunia. On physical examination, you find a well-demarcated white plaque of thickened, crinkled skin (FIGURE 1). A wet mount shows parabasal cells and no lactobacilli.

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus and atrophic vagina.

Treatment: Halobetasol ointment, an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid, once or twice daily; along with estradiol cream (0.5 g intravaginally) 3 times a week.

Lichen sclerosus is a skin disease found most often on the vulva of postmenopausal women, although it also can affect prepubertal children and reproductive-age women. Lichen sclerosus is multifactorial in pathogenesis, including prominent autoimmune factors, local environmental factors, and genetic predisposition.1

Although there is no cure for lichen sclerosus, the symptoms and clinical abnormalities usually can be well managed with ultra-potent topical corticosteroids. However, scarring and architectural changes are not reversible. Moreover, poorly controlled lichen sclerosus exhibits malignant transformation on anogenital skin in about 3% of affected patients.

The standard of care is application of an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid ointment once or twice daily until the skin texture normalizes again. The most common of such corticosteroids are clobetasol, halobetasol, and betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle (betamethasone dipropionate in the usual vehicle is only a medium-high medication in terms of potency.) One of us (L.E.) finds that some women experience irritation with generic clobetasol.

The ointment form of the selected corticosteroid is preferred, as creams are irritating to the vulva in most women because they contain more alcohols and preservatives than ointments do. The amount to be used is very small—far smaller than the pea-sized amount often suggested. By using this smaller amount, we avoid spread to the surrounding hair-bearing skin, which is at greater risk for steroid dermatitis and atrophy than the modified mucous membranes.

Related video: Lichen sclerosis: My approach to treatment Michael Baggish, MD

Even asymptomatic lichen sclerosus can progress

Most vulvologists agree that when the skin normalizes (not when symptoms subside), it is best to either decrease the frequency of application of the ultra-potent corticosteroid to two or three times a week, or to continue daily use with a lower-potency corticosteroid such as triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. Discontinuation of therapy usually results in recurrence.2

Treatment should not be based solely on symptoms, as asymptomatic lichen sclerosus can progress and cause permanent scarring and an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.

Although no studies have shown a decreased risk for squamous cell carcinoma with ongoing use of a corticosteroid, vulvologists have observed that malignant transformation occurs uniformly in the setting of poorly controlled lichen sclerosus. Immune dysregulation and inflammation may play an important role, so careful management to minimize inflammation may help prevent a malignancy.3

Secondary treatment choices

Secondary choices for lichen sclerosus include the topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel) but not testosterone, which has been shown to be ineffective. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are useful but often burn upon application, and they are “black-boxed” for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma. Therefore, although squamous cell carcinoma associated with their use is extraordinarily uncommon, patients should be advised of these risks, particularly because lichen sclerosus already exhibits this association.

Most postmenopausal women with lichen sclerosus also exhibit hypothyroidism, so they should be monitored for this. However, thyroid function testing in 18 children showed no evidence of hypothyroidism in that age group (L.E. unpublished data).

Estrogen replacement may be advised

Postmenopausal women who have prominent introital lichen sclerosus or dyspareunia should receive estrogen replacement of some type so that there is only one cause, rather than two, for their dyspareunia, thinning, fragility, and inelasticity.

Women with well-controlled lichen sclerosus should be followed twice a year to ensure that their disease remains suppressed with ongoing therapy, and to evaluate for active disease, adverse effects of therapy, and the appearance of dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma.

Women with lichen sclerosus occasionally experience discomfort after their clinical skin disease has cleared. These women now have developed vulvodynia triggered by their lichen sclerosus.

Related series: Vulvar Pain Syndromes—A 3-part roundtable

Part 1. Making the correct diagnosis (September 2011)

Part 2. A bounty of treatments—but not all of them proven (October 2011)

Part 3. Causes and treatment of vestibulodynia (November 2011)

CASE 2. IS IT REALLY CHRONIC YEAST INFECTION?

A 36-year-old woman consults you about her history of chronic yeast infection that manifests as introital burning, discharge, and dyspareunia. She is otherwise healthy, except for irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia.

Physical examination reveals a mild patchy redness of the vestibule and surrounding modified mucous membranes (FIGURE 2). Gentle probing with a cotton swab triggers exquisite pain in the vestibule, with slight extension to the labia minora. A wet mount shows no evidence of increased white blood cells, parabasal cells, clue cells, or yeast forms. Lactobacilli are abundant.

Diagnosis: Vulvodynia, with a nearly vestibulodynia pattern.

Treatment: Venlafaxine and pelvic floor physical therapy.

Vulvodynia is a genital pain syndrome defined as sensations of chronic burning, irritation, rawness, and soreness in the absence of objective disease and infection that could explain the discomfort. Vulvodynia occurs in approximately 7% to 8% of women.4

Vulvodynia generally is believed to be a multifactorial symptom, occurring as a result of pelvic floor dysfunction and neuropathic pain,5,6 with anxiety/depression issues exacerbating symptoms. Some recent studies have shown the presence of biochemical mediators of inflammation in the absence of clinical and histologic inflammation.7 Discomfort often is worsened by infections or the application of common irritants (creams, panty liners, soaps, some topical anesthetics). Estrogen deficiency is another common exacerbating factor.

Women tend to exhibit other pain syndromes such as chronic headaches, fibromyalgia, temperomandibular disorder, or premenstrual syndrome, as well as prominent anxiety, depression, sleep disorder, and so on.

Almost uniformly present are symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, such as constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis or urinary symptoms in the absence of a urinary tract infection. These women also are frequently unusually intolerant of medications.

Classifying vulvodynia

There are two primary patterns of vulvodynia. The first and most common is vestibulodynia, formerly called vulvar vestibulitis. The term vestibulitis was eliminated to reflect the absence of clinical and histologic inflammation. Vestibulodynia refers to pain that is always limited to the vestibule. Generalized vulvodynia, however, extends beyond the vestibule, is migratory, or does not include the vestibule.

Several vulvologists have found that many patients exhibit features of both types of vulvodynia, and these patterns probably exist on a spectrum. The difference is probably unimportant in clinical practice, except that vestibulodynia can be treated with vestibulectomy.

How we manage vulvodynia

We focus on pelvic floor physical therapy and on the provision of medication for neuropathic pain, which is initiated at very small doses and gradually increased to active doses.8 The medications used and the ultimate doses often required include:

- amitriptyline or desipramine 150 mg

- gabapentin 600 to 1,200 mg three times daily

- venlafaxine XR 150 mg daily

- pregabalin 150 mg twice a day

- duloxetine 60 mg a day.

Compounded amitriptyline 2% with baclofen 2% cream applied three times daily is beneficial for many patients, and topical lidocaine jelly 2% or ointment 5% (which often burns) can help provide immediate temporary relief.

Most patients require sex therapy and counseling for maximal improvement. Women with vestibulodynia in whom these therapies fail are good candidates for vestibulectomy if their pain is strictly limited to the vestibule. Fortunately, most women do not require this aggressive therapy.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; July 2013)

CASE 3. SEVERE ITCHING DISRUPTS SLEEP

A 34-year-old patient reports excruciating itching, with disruption of daily activities and sleep. She has been treated for candidiasis on multiple occasions, but in your office her wet mount and confirmatory culture are negative. Physical examination reveals a pink, lichenified plaque with excoriation (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Lichen simplex chronicus.

Treatment: Ultra-potent corticosteroid ointment applied very sparingly twice daily and covered with petroleum jelly. You also order nighttime sedation with amitriptyline to break the itch-scratch cycle. When the patient’s itching resolves and her skin clears, you taper her off the corticosteroid, warning her that recurrence is likely, and instruct her to restart the medication immediately should itching recur.

Lichen simplex chronicus (formerly called squamous hyperplasia or hyperplastic dystrophy, and also known as eczema, neurodermatitis, or localized atopic dermatitis) occurs when irritation from any cause produces itching in a predisposed person. The subsequent scratching and rubbing both produce the rash and exacerbate the irritation that drives the itching, even after the original cause is gone. The rubbing and scratching perpetuate the irritation and itching, producing the “itch-scratch” cycle.

The appearance of lichen simplex chronicus is produced by rubbing (where the skin thickens and lichenifies) or scratching (where the skin becomes red with linear erosions, called excoriations, caused by fingernails).

The initial trigger for lichen simplex chronicus often is an infection—often yeast—but overwashing, stress, sweat, heat, urine, irritating lubricants, and use of panty liners also may precipitate the itching. At the office visit, the original infection or other cause of irritation often is no longer present, and only lichen simplex chronicus can be identified.

How to treat lichen simplex chronicus

Management of lichen simplex chronicus requires very sparing application of an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid (clobetasol, halobetasol, or betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle ointment) twice daily, with the ointment covered with petroleum jelly. Care also must be taken to avoid irritants.

In addition, nighttime sedation helps to interrupt the itch-scratch cycle by preventing rubbing during sleep.

When the skin appears normal and itching has resolved, taper the medication down or off, warning the patient that recurrence is common with any future irritation.

Restart therapy immediately upon recurrence to prevent lichenification and chronic problems.

Second-line medications include calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus). Although these agents do not contribute to atrophy, they are less effective than topical corticosteroids,9 cost more, and can cause burning upon application.

Unlike lichen sclerosus, lichen simplex chronicus does not always recur upon cessation of treatment, and there is no need for concern about an increased risk of malignancy or significant scarring.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

CASE 4. ORAL AND VULVAR INVOLVEMENT

A 73-year-old patient seeks your help in alleviating longstanding introital itching and rawness, with dyspareunia. She has tried topical estradiol cream intravaginally three times weekly in combination with weekly fluconazole, to no avail.

Physical examination reveals deep red patches and erosions of the vestibule, with complete resorption of the labia minora (FIGURE 4). Patchy redness of the vagina is apparent as well, so you examine the patient’s mouth and find deep redness of the gingivae and erosions of the buccal mucosae, with surrounding white, lacy papules. A wet mount shows a marked increase in lymphocytes and parabasal cells, with a pH of more than 7.

Diagnosis: After correlating the vulvar and oral findings, you make a diagnosis of lichen planus.

Treatment: You initiate halobetasol ointment twice daily, to be applied to the vulva. You also continue vaginal estradiol cream but add hydrocortisone acetate 200 mg compounded vaginal suppositories nightly, as well as clobetasol gel to be applied to oral lesions three times a day. You follow the patient closely for secondary yeast of the mouth and vagina.

Erosive multimucosal lichen planus is a disease of cell-mediated immunity that overwhelmingly affects menopausal women. The most common surfaces involved are the mouth, vagina, rectal mucosa, and vulva; usually, at least two surfaces are affected. The esophagus, extra-auditory canals, nasal mucosa, and eyes also can be involved. Dry, extragenital skin usually is not affected in the setting of erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus.

Vulvar lichen planus most often is controlled with ultra-potent topical corticosteroids (again, clobetasol, halobetasol, or betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle), but other mucosal surfaces often are more difficult to manage. Although there is no definitive cure for this condition, careful local care, estrogen replacement, and suppression of oral and vulvovaginal candidiasis usually provide relief.

Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) sometimes are useful in patients who improve only partially after treatment with a topical corticosteroid, provided burning with application is tolerable.10 Systemic immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha blockers (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab), as well as oral retinoids, can be added for more recalcitrant disease.11

How to manage disease that affects the vagina

When the vagina is involved in lichen planus, treatment is important to prevent scarring, as well as rawness and pain from irritant contact dermatitis caused by purulent vaginal secretions. Occasionally, a 25-mg hydrocortisone acetate rectal suppository inserted into the vagina nightly improves vaginal lichen planus, but sometimes more potent suppositories, such as doses of 100 to 200 mg, may be compounded. Dilators should be inserted daily to prevent vaginal synechiae.

Oral involvement requires targeted treatment

The mouth is almost always involved in lichen planus. If a dermatologist is not involved in patient care, a prescription for dexamethasone/nystatin elixir (50:50) (5 mL swish, hold, and spit four times daily) can improve oral symptoms remarkably. Alternatively, clobetasol gel applied to affected areas of the mouth three or four times daily can be helpful. Secondary yeast of the vagina and mouth are common with the use of topical corticosteroids.

Careful clinical follow-up is advised

Like uncontrolled lichen sclerosus, erosive lichen planus of the vulva produces scarring and sometimes eventuates into squamous cell carcinoma. Therefore, careful clinical surveillance is warranted. And therapy must be continued to prevent recurrence of lichen planus (as it must be for lichen sclerosus), scarring, and to decrease the risk of squamous cell carcinoma. And like lichen sclerosus, lichen planus sometimes triggers vulvodynia.

CASE 5. MULTIPLE BOILS IN THE GROIN

A 31-year-old morbidly obese African American woman comes to your office with continually evolving boils in the groin. A culture shows Bacterioides spp, Escherichia coli, and Peptococcus spp. In the past, multiple courses of various antibiotics have provided only modest relief.

Physical examination reveals fluctuant nodules, scars, and draining sinus tracts of the hair-bearing vulva and crural crease (FIGURE 5). The axillae are clear.

Diagnosis: Hidradenitis suppurativa.

Treatment: The patient begins taking minocycline 100 mg twice daily. Because she is a smoker, you refer her to an aggressive primary care provider for smoking cessation and weight loss management.

Three months later, the patient is developing only about two nodules a month, managed by early intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is sometimes called inverse acne because the underlying pathogenesis is similar to cystic acne. Follicular plugging with keratin debris occurs, with additional keratin, sebaceous material, and normal skin bacteria trapped below the occlusion and distending the follicle. As the follicle wall stretches, thins, and allows for leakage of keratin debris into surrounding dermis, a brisk foreign-body response produces a noninfectious abscess.

Hidradenitis suppurativa affects more than 2% of the population.12 It appears only in areas of the body that contain apocrine glands and in individuals who have double- or triple-outlet follicles that predispose them to follicular occlusion. Therefore, this disease has a genetic component.

Other risk factors include male sex, African genetic background, obesity, and smoking. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome is significantly higher in individuals with hidradenitis suppurativa than in the general population.13

Recommended management

Treatments include:

- chronic antibiotics with nonspecific anti-inflammatory activity (tetracyclines, erythromycin, clindamycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole)

- intralesional injection of corticosteroids for early nodules (which often aborts their development)

- TNF alpha blockers (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab)14–16

- surgical removal of affected skin—the definitive therapy.

Note, however, that anogenital hidradenitis often is too extensive for surgery to be practical. In patients who have localized hidradenitis, primary excision is an excellent early therapy, provided the patient is advised that recurrence may occur in apocrine-containing nearby skin. Aggressive curettage of the roof of the cysts has been performed by some clinicians with good response.

Don’t overlook adjuvant approaches

Smoking cessation and weight loss often are useful.

Other therapies backed by anecdotal evidence include oral contraceptives or spironolactone for their anti-androgen effect, as well as metformin, a more recently studied agent.

Local care with antibacterial soaps and topical antibiotics may be useful for some women.

MORE CASES TO COME

In Part 2 of this series, which will appear in the June 2014 issue of OBG Management, we will discuss the following cases:

- atrophic vagina and atrophic vaginitis

- contact dermatitis

- vulvar aphthae

- desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

- psoriasis.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

Nearly one in every six women will experience chronic vulvar symptoms at some point, from ongoing itching to sensations of rawness, burning, or dyspareunia. Regrettably, clinicians generally are taught only a few possible causes for these symptoms, primarily infections such as yeast, bacterial vaginosis, herpes simplex virus, or anogenital warts. However, infections rarely produce chronic symptoms that do not respond, at least temporarily, to therapy.

In this two-part series, we focus on a total of 10 cases of vulvar symptoms, zeroing in on diagnosis and treatment. In this first part, we describe five patient scenarios illustrating the diagnosis and treatment of:

- lichen sclerosus

- vulvodynia

- lichen simplex chronicus

- lichen planus

- hidradenitis suppurativa.

In many chronic cases, more than one entity is the cause

Specific skin diseases, sensations of rawness from various external and internal irritants, neuropathy, and psychological issues are all much more common causes of chronic vulvar symptoms than infection. Moreover, most women with chronic vulvar symptoms have more than one entity producing their discomfort.

Very often, the cause of a patient’s symptoms is not clear at the first visit, with nonspecific redness or even normal skin seen on examination. Pathognomonic skin findings can be obscured by irritant contact dermatitis caused by unnecessary medications or overwashing, atrophic vaginitis, and/or rubbing and scratching. In such cases, obvious abnormalities must be eliminated and the patient reevaluated to definitively discover and treat the cause of the symptoms.

CASE 1. ANOGENITAL ITCHING AND DYSPAREUNIA

A 62-year-old woman schedules a visit to address her anogenital itching. She reports pain with scratching and has developed introital dyspareunia. On physical examination, you find a well-demarcated white plaque of thickened, crinkled skin (FIGURE 1). A wet mount shows parabasal cells and no lactobacilli.

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus and atrophic vagina.

Treatment: Halobetasol ointment, an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid, once or twice daily; along with estradiol cream (0.5 g intravaginally) 3 times a week.

Lichen sclerosus is a skin disease found most often on the vulva of postmenopausal women, although it also can affect prepubertal children and reproductive-age women. Lichen sclerosus is multifactorial in pathogenesis, including prominent autoimmune factors, local environmental factors, and genetic predisposition.1

Although there is no cure for lichen sclerosus, the symptoms and clinical abnormalities usually can be well managed with ultra-potent topical corticosteroids. However, scarring and architectural changes are not reversible. Moreover, poorly controlled lichen sclerosus exhibits malignant transformation on anogenital skin in about 3% of affected patients.

The standard of care is application of an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid ointment once or twice daily until the skin texture normalizes again. The most common of such corticosteroids are clobetasol, halobetasol, and betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle (betamethasone dipropionate in the usual vehicle is only a medium-high medication in terms of potency.) One of us (L.E.) finds that some women experience irritation with generic clobetasol.

The ointment form of the selected corticosteroid is preferred, as creams are irritating to the vulva in most women because they contain more alcohols and preservatives than ointments do. The amount to be used is very small—far smaller than the pea-sized amount often suggested. By using this smaller amount, we avoid spread to the surrounding hair-bearing skin, which is at greater risk for steroid dermatitis and atrophy than the modified mucous membranes.

Related video: Lichen sclerosis: My approach to treatment Michael Baggish, MD

Even asymptomatic lichen sclerosus can progress

Most vulvologists agree that when the skin normalizes (not when symptoms subside), it is best to either decrease the frequency of application of the ultra-potent corticosteroid to two or three times a week, or to continue daily use with a lower-potency corticosteroid such as triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. Discontinuation of therapy usually results in recurrence.2

Treatment should not be based solely on symptoms, as asymptomatic lichen sclerosus can progress and cause permanent scarring and an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.

Although no studies have shown a decreased risk for squamous cell carcinoma with ongoing use of a corticosteroid, vulvologists have observed that malignant transformation occurs uniformly in the setting of poorly controlled lichen sclerosus. Immune dysregulation and inflammation may play an important role, so careful management to minimize inflammation may help prevent a malignancy.3

Secondary treatment choices

Secondary choices for lichen sclerosus include the topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel) but not testosterone, which has been shown to be ineffective. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are useful but often burn upon application, and they are “black-boxed” for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma. Therefore, although squamous cell carcinoma associated with their use is extraordinarily uncommon, patients should be advised of these risks, particularly because lichen sclerosus already exhibits this association.

Most postmenopausal women with lichen sclerosus also exhibit hypothyroidism, so they should be monitored for this. However, thyroid function testing in 18 children showed no evidence of hypothyroidism in that age group (L.E. unpublished data).

Estrogen replacement may be advised

Postmenopausal women who have prominent introital lichen sclerosus or dyspareunia should receive estrogen replacement of some type so that there is only one cause, rather than two, for their dyspareunia, thinning, fragility, and inelasticity.

Women with well-controlled lichen sclerosus should be followed twice a year to ensure that their disease remains suppressed with ongoing therapy, and to evaluate for active disease, adverse effects of therapy, and the appearance of dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma.

Women with lichen sclerosus occasionally experience discomfort after their clinical skin disease has cleared. These women now have developed vulvodynia triggered by their lichen sclerosus.

Related series: Vulvar Pain Syndromes—A 3-part roundtable

Part 1. Making the correct diagnosis (September 2011)

Part 2. A bounty of treatments—but not all of them proven (October 2011)

Part 3. Causes and treatment of vestibulodynia (November 2011)

CASE 2. IS IT REALLY CHRONIC YEAST INFECTION?

A 36-year-old woman consults you about her history of chronic yeast infection that manifests as introital burning, discharge, and dyspareunia. She is otherwise healthy, except for irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia.

Physical examination reveals a mild patchy redness of the vestibule and surrounding modified mucous membranes (FIGURE 2). Gentle probing with a cotton swab triggers exquisite pain in the vestibule, with slight extension to the labia minora. A wet mount shows no evidence of increased white blood cells, parabasal cells, clue cells, or yeast forms. Lactobacilli are abundant.

Diagnosis: Vulvodynia, with a nearly vestibulodynia pattern.

Treatment: Venlafaxine and pelvic floor physical therapy.

Vulvodynia is a genital pain syndrome defined as sensations of chronic burning, irritation, rawness, and soreness in the absence of objective disease and infection that could explain the discomfort. Vulvodynia occurs in approximately 7% to 8% of women.4

Vulvodynia generally is believed to be a multifactorial symptom, occurring as a result of pelvic floor dysfunction and neuropathic pain,5,6 with anxiety/depression issues exacerbating symptoms. Some recent studies have shown the presence of biochemical mediators of inflammation in the absence of clinical and histologic inflammation.7 Discomfort often is worsened by infections or the application of common irritants (creams, panty liners, soaps, some topical anesthetics). Estrogen deficiency is another common exacerbating factor.

Women tend to exhibit other pain syndromes such as chronic headaches, fibromyalgia, temperomandibular disorder, or premenstrual syndrome, as well as prominent anxiety, depression, sleep disorder, and so on.

Almost uniformly present are symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, such as constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis or urinary symptoms in the absence of a urinary tract infection. These women also are frequently unusually intolerant of medications.

Classifying vulvodynia

There are two primary patterns of vulvodynia. The first and most common is vestibulodynia, formerly called vulvar vestibulitis. The term vestibulitis was eliminated to reflect the absence of clinical and histologic inflammation. Vestibulodynia refers to pain that is always limited to the vestibule. Generalized vulvodynia, however, extends beyond the vestibule, is migratory, or does not include the vestibule.

Several vulvologists have found that many patients exhibit features of both types of vulvodynia, and these patterns probably exist on a spectrum. The difference is probably unimportant in clinical practice, except that vestibulodynia can be treated with vestibulectomy.

How we manage vulvodynia

We focus on pelvic floor physical therapy and on the provision of medication for neuropathic pain, which is initiated at very small doses and gradually increased to active doses.8 The medications used and the ultimate doses often required include:

- amitriptyline or desipramine 150 mg

- gabapentin 600 to 1,200 mg three times daily

- venlafaxine XR 150 mg daily

- pregabalin 150 mg twice a day

- duloxetine 60 mg a day.

Compounded amitriptyline 2% with baclofen 2% cream applied three times daily is beneficial for many patients, and topical lidocaine jelly 2% or ointment 5% (which often burns) can help provide immediate temporary relief.

Most patients require sex therapy and counseling for maximal improvement. Women with vestibulodynia in whom these therapies fail are good candidates for vestibulectomy if their pain is strictly limited to the vestibule. Fortunately, most women do not require this aggressive therapy.

Related article: Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; July 2013)

CASE 3. SEVERE ITCHING DISRUPTS SLEEP

A 34-year-old patient reports excruciating itching, with disruption of daily activities and sleep. She has been treated for candidiasis on multiple occasions, but in your office her wet mount and confirmatory culture are negative. Physical examination reveals a pink, lichenified plaque with excoriation (FIGURE 3).

Diagnosis: Lichen simplex chronicus.

Treatment: Ultra-potent corticosteroid ointment applied very sparingly twice daily and covered with petroleum jelly. You also order nighttime sedation with amitriptyline to break the itch-scratch cycle. When the patient’s itching resolves and her skin clears, you taper her off the corticosteroid, warning her that recurrence is likely, and instruct her to restart the medication immediately should itching recur.

Lichen simplex chronicus (formerly called squamous hyperplasia or hyperplastic dystrophy, and also known as eczema, neurodermatitis, or localized atopic dermatitis) occurs when irritation from any cause produces itching in a predisposed person. The subsequent scratching and rubbing both produce the rash and exacerbate the irritation that drives the itching, even after the original cause is gone. The rubbing and scratching perpetuate the irritation and itching, producing the “itch-scratch” cycle.

The appearance of lichen simplex chronicus is produced by rubbing (where the skin thickens and lichenifies) or scratching (where the skin becomes red with linear erosions, called excoriations, caused by fingernails).

The initial trigger for lichen simplex chronicus often is an infection—often yeast—but overwashing, stress, sweat, heat, urine, irritating lubricants, and use of panty liners also may precipitate the itching. At the office visit, the original infection or other cause of irritation often is no longer present, and only lichen simplex chronicus can be identified.

How to treat lichen simplex chronicus

Management of lichen simplex chronicus requires very sparing application of an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid (clobetasol, halobetasol, or betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle ointment) twice daily, with the ointment covered with petroleum jelly. Care also must be taken to avoid irritants.

In addition, nighttime sedation helps to interrupt the itch-scratch cycle by preventing rubbing during sleep.

When the skin appears normal and itching has resolved, taper the medication down or off, warning the patient that recurrence is common with any future irritation.

Restart therapy immediately upon recurrence to prevent lichenification and chronic problems.

Second-line medications include calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus). Although these agents do not contribute to atrophy, they are less effective than topical corticosteroids,9 cost more, and can cause burning upon application.

Unlike lichen sclerosus, lichen simplex chronicus does not always recur upon cessation of treatment, and there is no need for concern about an increased risk of malignancy or significant scarring.

Related article: New treatment option for vulvar and vaginal atrophy Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (News for your Practice; May 2013)

CASE 4. ORAL AND VULVAR INVOLVEMENT

A 73-year-old patient seeks your help in alleviating longstanding introital itching and rawness, with dyspareunia. She has tried topical estradiol cream intravaginally three times weekly in combination with weekly fluconazole, to no avail.

Physical examination reveals deep red patches and erosions of the vestibule, with complete resorption of the labia minora (FIGURE 4). Patchy redness of the vagina is apparent as well, so you examine the patient’s mouth and find deep redness of the gingivae and erosions of the buccal mucosae, with surrounding white, lacy papules. A wet mount shows a marked increase in lymphocytes and parabasal cells, with a pH of more than 7.

Diagnosis: After correlating the vulvar and oral findings, you make a diagnosis of lichen planus.

Treatment: You initiate halobetasol ointment twice daily, to be applied to the vulva. You also continue vaginal estradiol cream but add hydrocortisone acetate 200 mg compounded vaginal suppositories nightly, as well as clobetasol gel to be applied to oral lesions three times a day. You follow the patient closely for secondary yeast of the mouth and vagina.

Erosive multimucosal lichen planus is a disease of cell-mediated immunity that overwhelmingly affects menopausal women. The most common surfaces involved are the mouth, vagina, rectal mucosa, and vulva; usually, at least two surfaces are affected. The esophagus, extra-auditory canals, nasal mucosa, and eyes also can be involved. Dry, extragenital skin usually is not affected in the setting of erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus.

Vulvar lichen planus most often is controlled with ultra-potent topical corticosteroids (again, clobetasol, halobetasol, or betamethasone dipropionate in an augmented vehicle), but other mucosal surfaces often are more difficult to manage. Although there is no definitive cure for this condition, careful local care, estrogen replacement, and suppression of oral and vulvovaginal candidiasis usually provide relief.

Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) sometimes are useful in patients who improve only partially after treatment with a topical corticosteroid, provided burning with application is tolerable.10 Systemic immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha blockers (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab), as well as oral retinoids, can be added for more recalcitrant disease.11

How to manage disease that affects the vagina

When the vagina is involved in lichen planus, treatment is important to prevent scarring, as well as rawness and pain from irritant contact dermatitis caused by purulent vaginal secretions. Occasionally, a 25-mg hydrocortisone acetate rectal suppository inserted into the vagina nightly improves vaginal lichen planus, but sometimes more potent suppositories, such as doses of 100 to 200 mg, may be compounded. Dilators should be inserted daily to prevent vaginal synechiae.

Oral involvement requires targeted treatment

The mouth is almost always involved in lichen planus. If a dermatologist is not involved in patient care, a prescription for dexamethasone/nystatin elixir (50:50) (5 mL swish, hold, and spit four times daily) can improve oral symptoms remarkably. Alternatively, clobetasol gel applied to affected areas of the mouth three or four times daily can be helpful. Secondary yeast of the vagina and mouth are common with the use of topical corticosteroids.

Careful clinical follow-up is advised

Like uncontrolled lichen sclerosus, erosive lichen planus of the vulva produces scarring and sometimes eventuates into squamous cell carcinoma. Therefore, careful clinical surveillance is warranted. And therapy must be continued to prevent recurrence of lichen planus (as it must be for lichen sclerosus), scarring, and to decrease the risk of squamous cell carcinoma. And like lichen sclerosus, lichen planus sometimes triggers vulvodynia.

CASE 5. MULTIPLE BOILS IN THE GROIN

A 31-year-old morbidly obese African American woman comes to your office with continually evolving boils in the groin. A culture shows Bacterioides spp, Escherichia coli, and Peptococcus spp. In the past, multiple courses of various antibiotics have provided only modest relief.

Physical examination reveals fluctuant nodules, scars, and draining sinus tracts of the hair-bearing vulva and crural crease (FIGURE 5). The axillae are clear.

Diagnosis: Hidradenitis suppurativa.

Treatment: The patient begins taking minocycline 100 mg twice daily. Because she is a smoker, you refer her to an aggressive primary care provider for smoking cessation and weight loss management.

Three months later, the patient is developing only about two nodules a month, managed by early intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is sometimes called inverse acne because the underlying pathogenesis is similar to cystic acne. Follicular plugging with keratin debris occurs, with additional keratin, sebaceous material, and normal skin bacteria trapped below the occlusion and distending the follicle. As the follicle wall stretches, thins, and allows for leakage of keratin debris into surrounding dermis, a brisk foreign-body response produces a noninfectious abscess.

Hidradenitis suppurativa affects more than 2% of the population.12 It appears only in areas of the body that contain apocrine glands and in individuals who have double- or triple-outlet follicles that predispose them to follicular occlusion. Therefore, this disease has a genetic component.

Other risk factors include male sex, African genetic background, obesity, and smoking. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome is significantly higher in individuals with hidradenitis suppurativa than in the general population.13

Recommended management

Treatments include:

- chronic antibiotics with nonspecific anti-inflammatory activity (tetracyclines, erythromycin, clindamycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole)

- intralesional injection of corticosteroids for early nodules (which often aborts their development)

- TNF alpha blockers (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab)14–16

- surgical removal of affected skin—the definitive therapy.

Note, however, that anogenital hidradenitis often is too extensive for surgery to be practical. In patients who have localized hidradenitis, primary excision is an excellent early therapy, provided the patient is advised that recurrence may occur in apocrine-containing nearby skin. Aggressive curettage of the roof of the cysts has been performed by some clinicians with good response.

Don’t overlook adjuvant approaches

Smoking cessation and weight loss often are useful.

Other therapies backed by anecdotal evidence include oral contraceptives or spironolactone for their anti-androgen effect, as well as metformin, a more recently studied agent.

Local care with antibacterial soaps and topical antibiotics may be useful for some women.

MORE CASES TO COME

In Part 2 of this series, which will appear in the June 2014 issue of OBG Management, we will discuss the following cases:

- atrophic vagina and atrophic vaginitis

- contact dermatitis

- vulvar aphthae

- desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

- psoriasis.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

- Doulaveri G, Armira K, Kouris A, et al. Genital vulvar lichen sclerosus in monozygotic twin women: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5(3):321–325.

- Virgili A, Minghetti S, Borghi A, Corazza M. Proactive maintenance therapy with a topical corticosteroid for vulvar lichen sclerosus: Preliminary results of a randomized study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(6):1316–1324.

- Brodrick B, Belkin ZR, Goldstein AT. Influence of treatments on prognosis for vulvar lichen sclerosus: Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(6):780–786.

- Harlow BL, Kunitz CG, Nguyen RH, Rydell SA, Turner RM, MacLehose RF. Prevalence of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of vulvodynia: Population-based estimates from two geographic regions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):40.e1–e8.

- Morin M, Bergeron S, Khalife S, Mayrand MH, Binik YM. Morphometry of the pelvic floor muscles in women with and without provoked vestibulodynia using 4D ultrasound. J Sex Med. 2014;11(3):776–785.

- Hampson JP, Reed BD, Clauw DJ, et al. Augmented central pain processing in vulvodynia. J Pain. 2013;14(6):579–589.

- Omoigui S. The biochemical origin of pain: the origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response. Part 2 of 3: Inflammatory profile of pain syndromes. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69(6):1169–1178.

- Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia guideline. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2005;9(1):40–51.

- Frankel HC, Qureshi AA. Comparative effectiveness of topical calcineurin inhibitors in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(2):113–123.

- Samycia M, Lin AN. Efficacy of topical calcineurin inhibitors in lichen planus. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16(4):221–229.

- Mirowski GW, Goddard A. Treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28(4):717–725.

- Vinding GR, Miller IM, Zarchi K, et al. The prevalence of inverse recurrent suppuration: A population-based study of possible hidradenitis suppurativa [published online ahead of print December 16, 2013]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.12787.

- Gold DA, Reeder VJ, Mahan MG, Hamzavi IH. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(4):699–703.

- Scheinfeld N. Hidradenitis suppurativa: A practical review of possible medical treatments based on over 350 hidradenitis patients. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(4):1.

- Kimball AB, Kerdel F, Adams D, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa:

A parallel randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(12):846–855. - Chinniah N, Cains GD. Moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa treated with biological therapies [published online ahead of print January 23, 2014]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.12136.

- Doulaveri G, Armira K, Kouris A, et al. Genital vulvar lichen sclerosus in monozygotic twin women: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5(3):321–325.

- Virgili A, Minghetti S, Borghi A, Corazza M. Proactive maintenance therapy with a topical corticosteroid for vulvar lichen sclerosus: Preliminary results of a randomized study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(6):1316–1324.

- Brodrick B, Belkin ZR, Goldstein AT. Influence of treatments on prognosis for vulvar lichen sclerosus: Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(6):780–786.

- Harlow BL, Kunitz CG, Nguyen RH, Rydell SA, Turner RM, MacLehose RF. Prevalence of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of vulvodynia: Population-based estimates from two geographic regions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):40.e1–e8.

- Morin M, Bergeron S, Khalife S, Mayrand MH, Binik YM. Morphometry of the pelvic floor muscles in women with and without provoked vestibulodynia using 4D ultrasound. J Sex Med. 2014;11(3):776–785.

- Hampson JP, Reed BD, Clauw DJ, et al. Augmented central pain processing in vulvodynia. J Pain. 2013;14(6):579–589.

- Omoigui S. The biochemical origin of pain: the origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response. Part 2 of 3: Inflammatory profile of pain syndromes. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69(6):1169–1178.

- Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia guideline. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2005;9(1):40–51.

- Frankel HC, Qureshi AA. Comparative effectiveness of topical calcineurin inhibitors in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(2):113–123.

- Samycia M, Lin AN. Efficacy of topical calcineurin inhibitors in lichen planus. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16(4):221–229.

- Mirowski GW, Goddard A. Treatment of vulvovaginal lichen planus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28(4):717–725.

- Vinding GR, Miller IM, Zarchi K, et al. The prevalence of inverse recurrent suppuration: A population-based study of possible hidradenitis suppurativa [published online ahead of print December 16, 2013]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.12787.

- Gold DA, Reeder VJ, Mahan MG, Hamzavi IH. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(4):699–703.

- Scheinfeld N. Hidradenitis suppurativa: A practical review of possible medical treatments based on over 350 hidradenitis patients. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(4):1.

- Kimball AB, Kerdel F, Adams D, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa:

A parallel randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(12):846–855. - Chinniah N, Cains GD. Moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa treated with biological therapies [published online ahead of print January 23, 2014]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.12136.

Read Part 2: Chronic vulvar irritation, itching, and pain. What is the diagnosis? (June 2014)