User login

COVID-19 continues to be a diminishing issue for U.S. children, as the number of new cases declined for the ninth consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The most recently infected children brought the total number of COVID-19 cases to just over 12.8 million since the pandemic began.

Other measures of COVID occurrence in children, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, also followed recent downward trends, although the sizes of the declines are beginning to decrease. Admissions dropped by 13.3% during the week ending March 26, but that followed declines of 25%, 20%, 26.5% and 24.4% for the 4 previous weeks, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The slowdown in ED visits started a couple of weeks earlier, but the decline is still ongoing. As of March 25, ED visits with a confirmed COVID diagnosis represented just 0.4% of all visits for children aged 0-11 years, down from 1.1% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 15. For children aged 12-15, the latest figure is just 0.2%, compared with 0.5% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 9, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Although he was speaking of the nation as a whole and not specifically of children, Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently told the Washington Post that, “unless something changes dramatically,” another major surge isn’t on the horizon.

That sentiment, however, was not entirely shared by Moderna’s chief medical officer, Paul Burton, MD, PhD. In an interview with WebMD, he said that another COVID wave is inevitable and that it’s too soon to dismantle the vaccine infrastructure: “We’ve come so far. We’ve put so much into this to now take our foot off the gas. I think it would be a mistake for public health worldwide.”

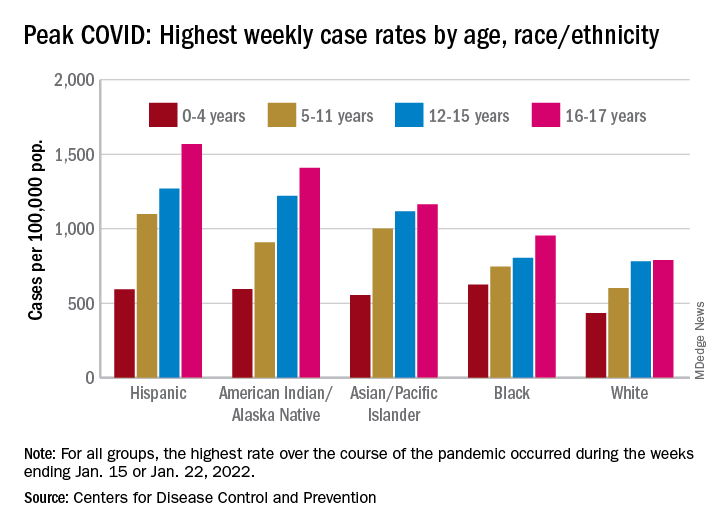

Disparities during the Omicron surge

As the country puts Omicron in its rear view mirror, a quick look back at the CDC data shows some differences in how children were affected. At the surge’s peak in early to mid-January, Hispanic children were the most likely to get COVID-19, with incidence highest in the older groups. (See graph.)

At their peak week of Jan. 2-8, Hispanic children aged 16-17 years had a COVID rate of 1,568 cases per 100,000 population, versus 790 per 100,000 for White children, whose peak occurred a week later, from Jan. 9 to 15. Hispanic children aged 5-11 (1,098 per 100,000) and 12-15 (1,269 per 100,000) also had the highest recorded rates of the largest racial/ethnic groups, while Black children had the highest one-week rate, 625 per 100,000, among the 0- to 4-year-olds, according to the CDC.

COVID-19 continues to be a diminishing issue for U.S. children, as the number of new cases declined for the ninth consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The most recently infected children brought the total number of COVID-19 cases to just over 12.8 million since the pandemic began.

Other measures of COVID occurrence in children, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, also followed recent downward trends, although the sizes of the declines are beginning to decrease. Admissions dropped by 13.3% during the week ending March 26, but that followed declines of 25%, 20%, 26.5% and 24.4% for the 4 previous weeks, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The slowdown in ED visits started a couple of weeks earlier, but the decline is still ongoing. As of March 25, ED visits with a confirmed COVID diagnosis represented just 0.4% of all visits for children aged 0-11 years, down from 1.1% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 15. For children aged 12-15, the latest figure is just 0.2%, compared with 0.5% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 9, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Although he was speaking of the nation as a whole and not specifically of children, Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently told the Washington Post that, “unless something changes dramatically,” another major surge isn’t on the horizon.

That sentiment, however, was not entirely shared by Moderna’s chief medical officer, Paul Burton, MD, PhD. In an interview with WebMD, he said that another COVID wave is inevitable and that it’s too soon to dismantle the vaccine infrastructure: “We’ve come so far. We’ve put so much into this to now take our foot off the gas. I think it would be a mistake for public health worldwide.”

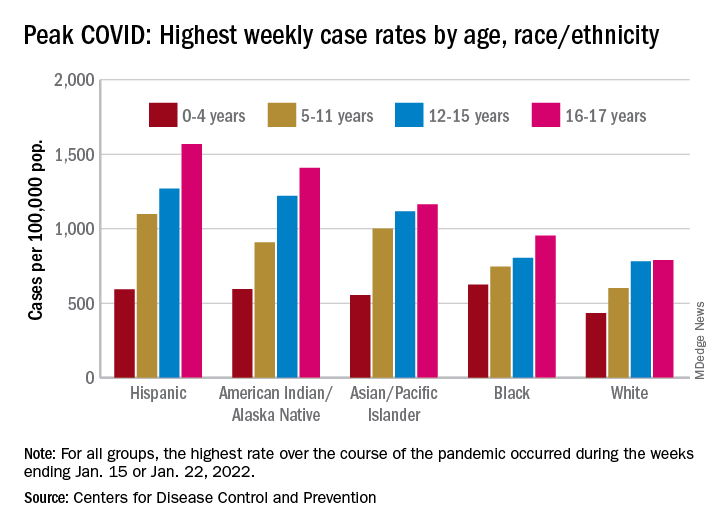

Disparities during the Omicron surge

As the country puts Omicron in its rear view mirror, a quick look back at the CDC data shows some differences in how children were affected. At the surge’s peak in early to mid-January, Hispanic children were the most likely to get COVID-19, with incidence highest in the older groups. (See graph.)

At their peak week of Jan. 2-8, Hispanic children aged 16-17 years had a COVID rate of 1,568 cases per 100,000 population, versus 790 per 100,000 for White children, whose peak occurred a week later, from Jan. 9 to 15. Hispanic children aged 5-11 (1,098 per 100,000) and 12-15 (1,269 per 100,000) also had the highest recorded rates of the largest racial/ethnic groups, while Black children had the highest one-week rate, 625 per 100,000, among the 0- to 4-year-olds, according to the CDC.

COVID-19 continues to be a diminishing issue for U.S. children, as the number of new cases declined for the ninth consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The most recently infected children brought the total number of COVID-19 cases to just over 12.8 million since the pandemic began.

Other measures of COVID occurrence in children, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, also followed recent downward trends, although the sizes of the declines are beginning to decrease. Admissions dropped by 13.3% during the week ending March 26, but that followed declines of 25%, 20%, 26.5% and 24.4% for the 4 previous weeks, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The slowdown in ED visits started a couple of weeks earlier, but the decline is still ongoing. As of March 25, ED visits with a confirmed COVID diagnosis represented just 0.4% of all visits for children aged 0-11 years, down from 1.1% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 15. For children aged 12-15, the latest figure is just 0.2%, compared with 0.5% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 9, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Although he was speaking of the nation as a whole and not specifically of children, Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently told the Washington Post that, “unless something changes dramatically,” another major surge isn’t on the horizon.

That sentiment, however, was not entirely shared by Moderna’s chief medical officer, Paul Burton, MD, PhD. In an interview with WebMD, he said that another COVID wave is inevitable and that it’s too soon to dismantle the vaccine infrastructure: “We’ve come so far. We’ve put so much into this to now take our foot off the gas. I think it would be a mistake for public health worldwide.”

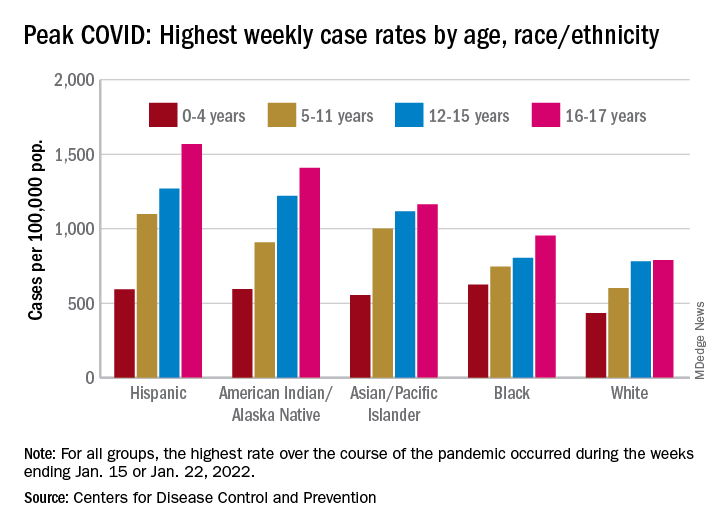

Disparities during the Omicron surge

As the country puts Omicron in its rear view mirror, a quick look back at the CDC data shows some differences in how children were affected. At the surge’s peak in early to mid-January, Hispanic children were the most likely to get COVID-19, with incidence highest in the older groups. (See graph.)

At their peak week of Jan. 2-8, Hispanic children aged 16-17 years had a COVID rate of 1,568 cases per 100,000 population, versus 790 per 100,000 for White children, whose peak occurred a week later, from Jan. 9 to 15. Hispanic children aged 5-11 (1,098 per 100,000) and 12-15 (1,269 per 100,000) also had the highest recorded rates of the largest racial/ethnic groups, while Black children had the highest one-week rate, 625 per 100,000, among the 0- to 4-year-olds, according to the CDC.