User login

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented with multiple anesthetic, annular, erythematous, scaly plaques with a raised border of 6 weeks’ duration that were unresponsive to topical steroid therapy. Four plaques were noted on the lower back ranging from 2 to 4 cm in diameter as well as a fifth plaque on the anterior portion of the right ankle that was approximately 6×6 cm. He denied fever, malaise, muscle weakness, changes in vision, or sensory deficits outside of the lesions themselves. The patient also denied any recent travel to endemic areas or exposure to armadillos.

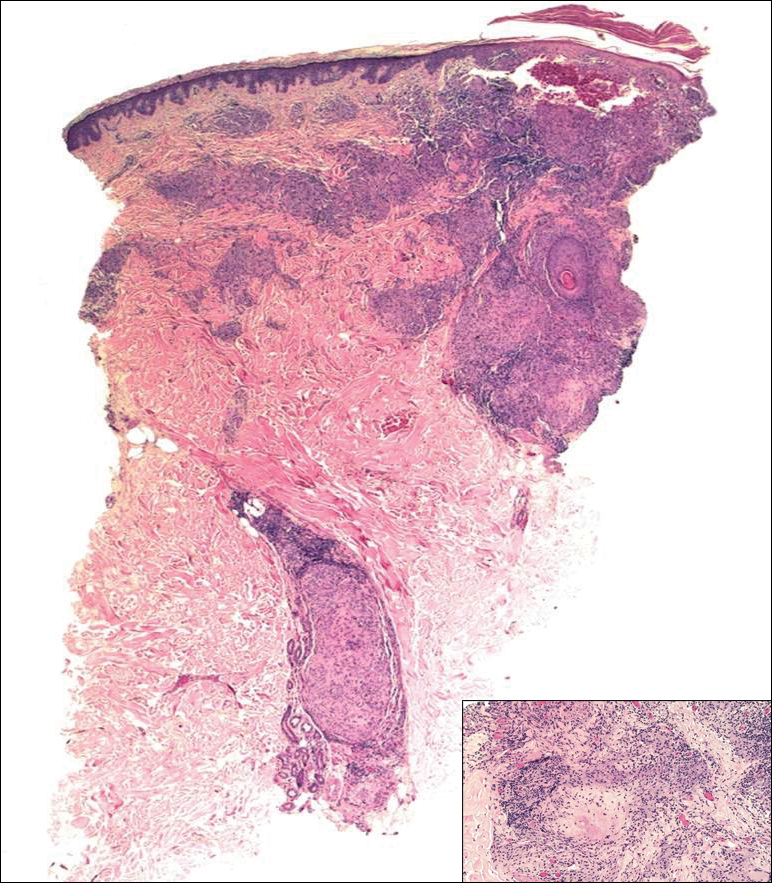

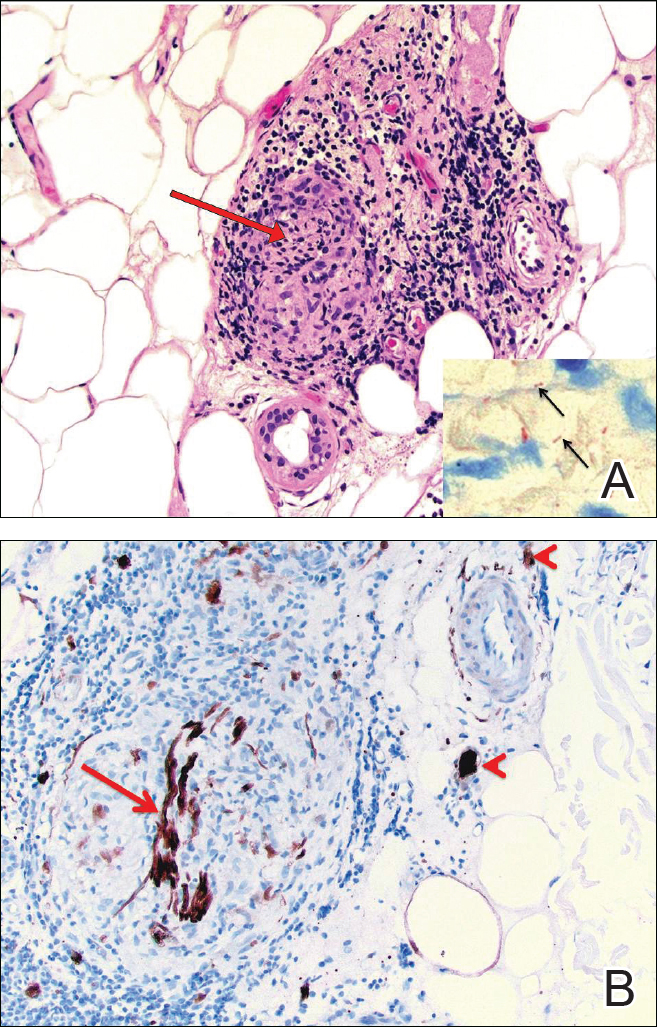

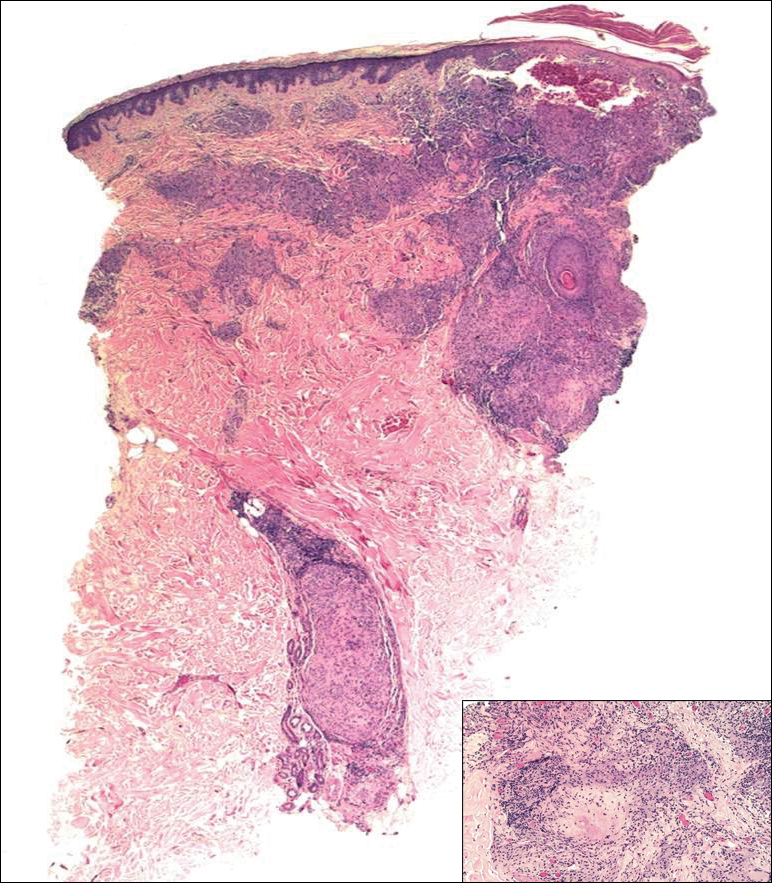

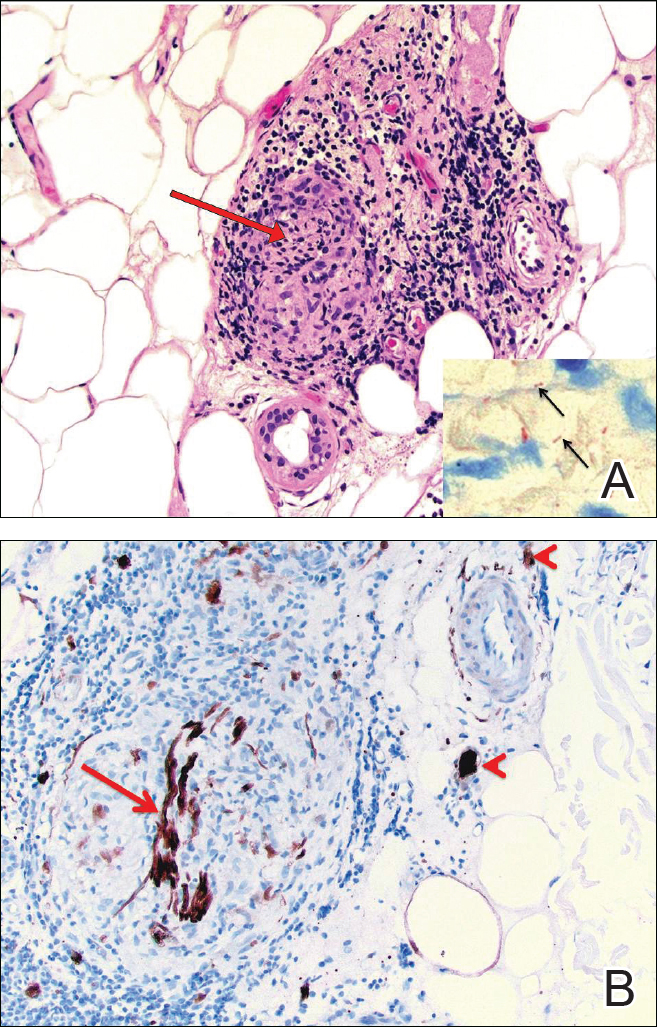

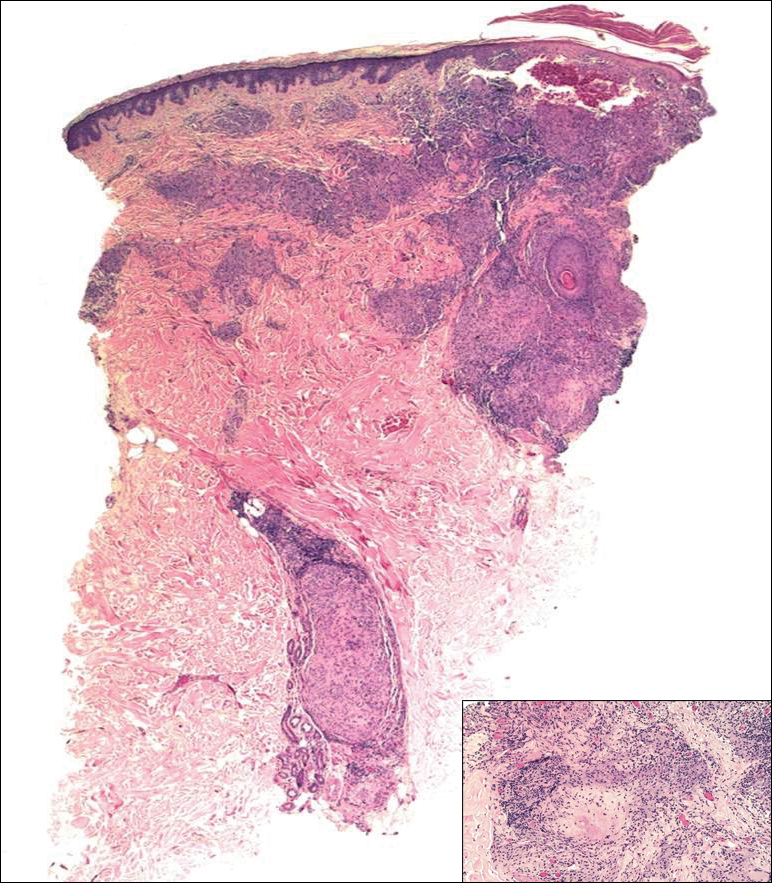

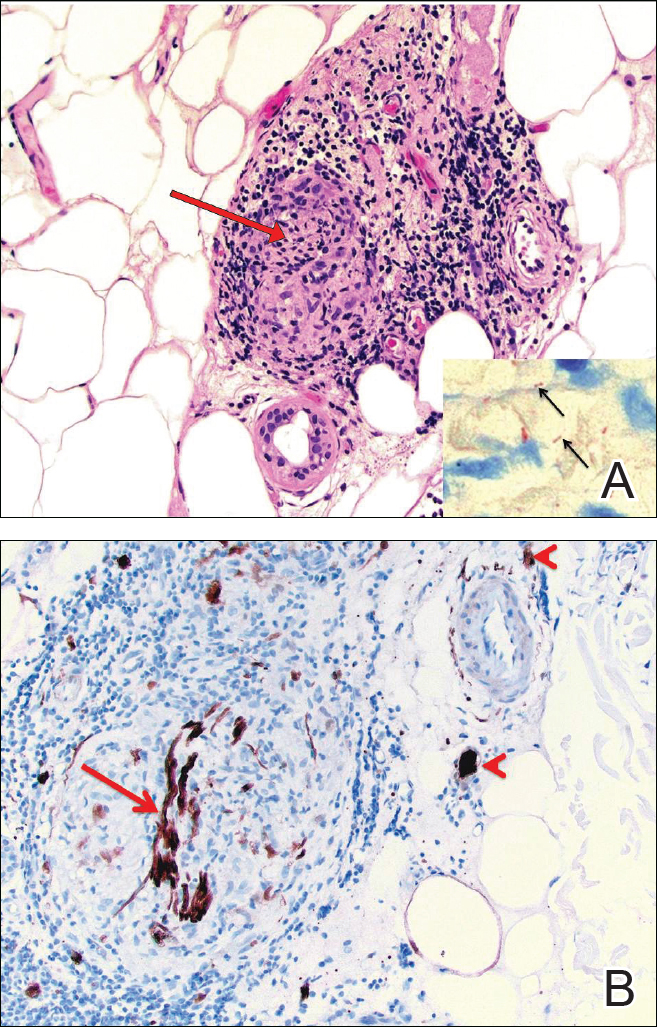

Biopsies were taken from lesions on the lumbar back and anterior aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a granulomatous infiltrate spreading along neurovascular structures (Figure 2). Granulomas also were identified in the dermal interstitium exhibiting partial necrosis (Figure 2 inset). Conspicuous distension of lymphovascular and perineural areas also was noted. Immunohistochemical studies with S-100 and neurofilament stains allowed insight into the pathomechanism of the clinically observed anesthesia, as nerve fibers were identified showing different stages of damage elicited by the granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Fite staining was positive for occasional bacilli within histiocytes (Figure 3A inset). Despite the clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical evidence, the patient had no known exposure to leprosy; consequently, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was ordered for confirmation of the diagnosis. Surprisingly, the PCR was positive for Mycobacterium leprae DNA. These findings were consistent with borderline tuberculoid leprosy.

The case was reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program (Baton Rouge, Louisiana). The patient was started on rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The lesions exhibited marked improvement after completion of therapy (Figure 1B).

Comment

Disease Transmission

Hansen disease, also known as leprosy, is a chronic granulomatous infectious disease that is caused by M leprae, an obligate intracellular bacillus aerobe.1 The mechanism of spread of M leprae is not clear. It is thought to be transmitted via respiratory droplets, though it may occur through injured skin.2 Studies have suggested that in addition to humans, nine-banded armadillos are a source of infection.2,3 Exposure to infected individuals, particularly multibacillary patients, increases the likelihood of contracting leprosy.2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 81 cases of Hansen disease were diagnosed in the United States in 2013,4 compared to 178 cases registered in 2015.5 Cases from Hawaii, Texas, California, Louisiana, New York, and Florida made up 72% (129/178) of the reported cases. There was an increase from 34 cases to 49 cases in Florida from 2014 to 2015.5 The spread of leprosy throughout Florida may be from the merge of 2 armadillo populations, an M leprae–infected population migrating east from Texas and one from south central Florida that historically had not been infected with M leprae until recently.3,6 Our patient did not have any known exposures to armadillos.

Classification and Presentation

The clinical presentation of Hansen disease is widely variable, as it can present at any point along a spectrum ranging from tuberculoid leprosy to lepromatous leprosy with borderline conditions in between, according to the Ridley-Jopling critera.7 The World Health Organization also classifies leprosy based on the number of acid-fast bacilli seen in a skin smear as either paucibacillary or multibacillary.2 The paucibacillary classification correlates with tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, and indeterminate leprosy, and multibacillary correlates with borderline lepromatous and lepromatous leprosy. Paucibacillary leprosy usually presents with a less dramatic clinical picture than multibacillary leprosy. The clinical presentation is dependent on the magnitude of immune response to M leprae.2

Paucibacillary infection occurs when the body generates a strong cell-mediated immune response against the bacteria,8 which causes the activation and proliferation of CD4 and CD8 T cells, limiting the spread of the mycobacterium. Subsequently, the patient typically presents with a mild clinical picture with few skin lesions and limited nerve involvement.8 The skin lesions are papules or plaques with raised borders that are usually hypopigmented on dark skin and erythematous on light skin. Nerve involvement in paucibacillary forms of leprosy include sensory impairment and anhidrosis within the lesions. Nerve enlargement usually affects superficial nerves, with the posterior tibial nerve being most commonly affected.

Multibacillary leprosy presents with systemic involvement due to a weak cell-mediated immune response. Patients generally present with diffuse, poorly defined nodules; greater nerve impairment; and other systemic symptoms such as blindness, swelling of the fingers and toes, and testicular atrophy (in men). Additionally, enlargement of the earlobes and widening of the nasal bridge may contribute to the appearance of leonine facies. Nerve impairment in multibacillary forms of leprosy may be more severe, including more diffuse sensory involvement (eg, stocking glove–pattern neuropathy, nerve-trunk palsies), which ultimately may lead to foot drop, claw toe, and lagophthalmos.8

In addition to the clinical presentation, the histology of the paucibacillary and multibacillary types differ. Multibacillary leprosy shows diffuse histiocytes without granulomas and multiple bacilli seen on Fite staining.8 In the paucibacillary form, there are well-formed granulomas with Langerhans giant cells and a perineural lymphocytic infiltrate seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining with rare acid-fast bacilli seen on Fite staining.

To diagnose leprosy, at least one of the following 3 clinical signs must be present: (1) a hypopigmented or erythematous lesion with loss of sensation, (2) thickened peripheral nerve, or (3) acid-fast bacilli on slit-skin smear.2

Management

The World Health Organization guidelines involve multidrug therapy over an extended period of time.2 For adults, the paucibacillary regimen includes rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The adult regimen for multibacillary leprosy includes clofazimine 300 mg once monthly and 50 mg once daily, in addition to rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 12 months. If classification cannot be determined, it is recommended the patient be treated for multibacillary disease.2

Reversal Reactions

During the course of the disease, patients may upgrade (to a less severe form) or downgrade (to a more severe form) between the tuberculoid, borderline, and lepromatous forms.8 The patient’s clinical picture also may change with complications of leprosy, which include type 1 and type 2 reactions. Type 1 reaction is a reversal reaction seen in 15% to 30% of patients at risk, usually those with borderline forms of leprosy.9 Reversal reactions usually manifest as erythema and edema of current skin lesions, formation of new tumid lesions, and tenderness of peripheral nerves with loss of nerve function.8 Treatment of reversal reactions involves systemic corticosteroids.10 Type 2 reaction is classified as erythema nodosum leprosum. It presents within the first 2 years of treatment in approximately 20% of lepromatous patients and approximately 10% of borderline lepromatous patients but is rare in paucibacillary infections.11 It presents with fever and crops of pink nodules and may include iritis, neuritis, lymphadenitis, orchitis, dactylitis, arthritis, and proteinuria.8 Treatment options for erythema nodosum leprosum include corticosteroids, clofazimine, and thalidomide.12,13

Conclusion

Hansen disease is a rare condition in the United States. This case is unique because, to our knowledge, it is the first known PCR-confirmed case of Hansen disease in Okeechobee County, Florida. Additionally, the patient had no known exposure to M leprae. Exposure is increasing due to the increased geographical range of infected armadillos. Infection rates also may rise due to travel to endemic countries. Initially lesions may appear as innocuous erythematous plaques. When they do not respond to standard therapy, infectious agents such as M leprae should be part of the differential diagnosis. Because hematoxylin and eosin staining does not always yield results, if clinical suspicion is present, PCR should be performed. If a patient meets the clinical and histological diagnosis, the case should be reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program.

After completion of treatment, our patient has shown excellent results. He has not yet demonstrated a reversal reaction; however, he may still be at risk, as it most commonly presents 2 months after starting treatment but can present years after treatment has been initiated.8 Cutaneous leprosy must be considered in the differential diagnosis for steroid-nonresponsive skin lesions, particularly in states such as Florida with a documented increase in incidence.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sharon Barrineau, ARNP (Okeechobee, Florida), for her acumen, contributions, and support on this case.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, 8th Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Truman RW, Singh P, Sharma R, et al. Probable zoonotic leprosy in the southern United States. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1626-1633.

- Adams DA, Fullerton K, Jajosky R, et al; Division of Notifiable Diseases and Healthcare Information, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC. Summary of notifiable diseases—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;62:1-122.

- A summary of Hansen’s disease in the United States—2015. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Hansen’s Disease Program. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hansensdisease/pdfs/hansens2015report.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- Loughry WJ, Truman RW, McDonough CM, et al. Is leprosy spreading among nine-banded armadillos in the southeastern United States? J Wildl Dis. 2009;45:144-152.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five group system. Int J Lepr. 1966;34:225-273.

- Lee DJ, Rea TH, Modlin RL. Leprosy. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, et al. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:338-381.

- Britton WJ. The management of leprosy reversal reactions. Lepr Rev. 1998;69:225-234.

- Manandhar R, LeMaster JW, Roche PW. Risk factors for erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1999;67:270-278.

- Lockwood DN. The management of erythema nodosum leprosum: current and future options. Lepr Rev. 1996;67:253-259.

- Jakeman P, Smith WC. Thalidomide in leprosy reaction. Lancet. 1994;343:432-433.

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented with multiple anesthetic, annular, erythematous, scaly plaques with a raised border of 6 weeks’ duration that were unresponsive to topical steroid therapy. Four plaques were noted on the lower back ranging from 2 to 4 cm in diameter as well as a fifth plaque on the anterior portion of the right ankle that was approximately 6×6 cm. He denied fever, malaise, muscle weakness, changes in vision, or sensory deficits outside of the lesions themselves. The patient also denied any recent travel to endemic areas or exposure to armadillos.

Biopsies were taken from lesions on the lumbar back and anterior aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a granulomatous infiltrate spreading along neurovascular structures (Figure 2). Granulomas also were identified in the dermal interstitium exhibiting partial necrosis (Figure 2 inset). Conspicuous distension of lymphovascular and perineural areas also was noted. Immunohistochemical studies with S-100 and neurofilament stains allowed insight into the pathomechanism of the clinically observed anesthesia, as nerve fibers were identified showing different stages of damage elicited by the granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Fite staining was positive for occasional bacilli within histiocytes (Figure 3A inset). Despite the clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical evidence, the patient had no known exposure to leprosy; consequently, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was ordered for confirmation of the diagnosis. Surprisingly, the PCR was positive for Mycobacterium leprae DNA. These findings were consistent with borderline tuberculoid leprosy.

The case was reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program (Baton Rouge, Louisiana). The patient was started on rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The lesions exhibited marked improvement after completion of therapy (Figure 1B).

Comment

Disease Transmission

Hansen disease, also known as leprosy, is a chronic granulomatous infectious disease that is caused by M leprae, an obligate intracellular bacillus aerobe.1 The mechanism of spread of M leprae is not clear. It is thought to be transmitted via respiratory droplets, though it may occur through injured skin.2 Studies have suggested that in addition to humans, nine-banded armadillos are a source of infection.2,3 Exposure to infected individuals, particularly multibacillary patients, increases the likelihood of contracting leprosy.2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 81 cases of Hansen disease were diagnosed in the United States in 2013,4 compared to 178 cases registered in 2015.5 Cases from Hawaii, Texas, California, Louisiana, New York, and Florida made up 72% (129/178) of the reported cases. There was an increase from 34 cases to 49 cases in Florida from 2014 to 2015.5 The spread of leprosy throughout Florida may be from the merge of 2 armadillo populations, an M leprae–infected population migrating east from Texas and one from south central Florida that historically had not been infected with M leprae until recently.3,6 Our patient did not have any known exposures to armadillos.

Classification and Presentation

The clinical presentation of Hansen disease is widely variable, as it can present at any point along a spectrum ranging from tuberculoid leprosy to lepromatous leprosy with borderline conditions in between, according to the Ridley-Jopling critera.7 The World Health Organization also classifies leprosy based on the number of acid-fast bacilli seen in a skin smear as either paucibacillary or multibacillary.2 The paucibacillary classification correlates with tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, and indeterminate leprosy, and multibacillary correlates with borderline lepromatous and lepromatous leprosy. Paucibacillary leprosy usually presents with a less dramatic clinical picture than multibacillary leprosy. The clinical presentation is dependent on the magnitude of immune response to M leprae.2

Paucibacillary infection occurs when the body generates a strong cell-mediated immune response against the bacteria,8 which causes the activation and proliferation of CD4 and CD8 T cells, limiting the spread of the mycobacterium. Subsequently, the patient typically presents with a mild clinical picture with few skin lesions and limited nerve involvement.8 The skin lesions are papules or plaques with raised borders that are usually hypopigmented on dark skin and erythematous on light skin. Nerve involvement in paucibacillary forms of leprosy include sensory impairment and anhidrosis within the lesions. Nerve enlargement usually affects superficial nerves, with the posterior tibial nerve being most commonly affected.

Multibacillary leprosy presents with systemic involvement due to a weak cell-mediated immune response. Patients generally present with diffuse, poorly defined nodules; greater nerve impairment; and other systemic symptoms such as blindness, swelling of the fingers and toes, and testicular atrophy (in men). Additionally, enlargement of the earlobes and widening of the nasal bridge may contribute to the appearance of leonine facies. Nerve impairment in multibacillary forms of leprosy may be more severe, including more diffuse sensory involvement (eg, stocking glove–pattern neuropathy, nerve-trunk palsies), which ultimately may lead to foot drop, claw toe, and lagophthalmos.8

In addition to the clinical presentation, the histology of the paucibacillary and multibacillary types differ. Multibacillary leprosy shows diffuse histiocytes without granulomas and multiple bacilli seen on Fite staining.8 In the paucibacillary form, there are well-formed granulomas with Langerhans giant cells and a perineural lymphocytic infiltrate seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining with rare acid-fast bacilli seen on Fite staining.

To diagnose leprosy, at least one of the following 3 clinical signs must be present: (1) a hypopigmented or erythematous lesion with loss of sensation, (2) thickened peripheral nerve, or (3) acid-fast bacilli on slit-skin smear.2

Management

The World Health Organization guidelines involve multidrug therapy over an extended period of time.2 For adults, the paucibacillary regimen includes rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The adult regimen for multibacillary leprosy includes clofazimine 300 mg once monthly and 50 mg once daily, in addition to rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 12 months. If classification cannot be determined, it is recommended the patient be treated for multibacillary disease.2

Reversal Reactions

During the course of the disease, patients may upgrade (to a less severe form) or downgrade (to a more severe form) between the tuberculoid, borderline, and lepromatous forms.8 The patient’s clinical picture also may change with complications of leprosy, which include type 1 and type 2 reactions. Type 1 reaction is a reversal reaction seen in 15% to 30% of patients at risk, usually those with borderline forms of leprosy.9 Reversal reactions usually manifest as erythema and edema of current skin lesions, formation of new tumid lesions, and tenderness of peripheral nerves with loss of nerve function.8 Treatment of reversal reactions involves systemic corticosteroids.10 Type 2 reaction is classified as erythema nodosum leprosum. It presents within the first 2 years of treatment in approximately 20% of lepromatous patients and approximately 10% of borderline lepromatous patients but is rare in paucibacillary infections.11 It presents with fever and crops of pink nodules and may include iritis, neuritis, lymphadenitis, orchitis, dactylitis, arthritis, and proteinuria.8 Treatment options for erythema nodosum leprosum include corticosteroids, clofazimine, and thalidomide.12,13

Conclusion

Hansen disease is a rare condition in the United States. This case is unique because, to our knowledge, it is the first known PCR-confirmed case of Hansen disease in Okeechobee County, Florida. Additionally, the patient had no known exposure to M leprae. Exposure is increasing due to the increased geographical range of infected armadillos. Infection rates also may rise due to travel to endemic countries. Initially lesions may appear as innocuous erythematous plaques. When they do not respond to standard therapy, infectious agents such as M leprae should be part of the differential diagnosis. Because hematoxylin and eosin staining does not always yield results, if clinical suspicion is present, PCR should be performed. If a patient meets the clinical and histological diagnosis, the case should be reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program.

After completion of treatment, our patient has shown excellent results. He has not yet demonstrated a reversal reaction; however, he may still be at risk, as it most commonly presents 2 months after starting treatment but can present years after treatment has been initiated.8 Cutaneous leprosy must be considered in the differential diagnosis for steroid-nonresponsive skin lesions, particularly in states such as Florida with a documented increase in incidence.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sharon Barrineau, ARNP (Okeechobee, Florida), for her acumen, contributions, and support on this case.

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented with multiple anesthetic, annular, erythematous, scaly plaques with a raised border of 6 weeks’ duration that were unresponsive to topical steroid therapy. Four plaques were noted on the lower back ranging from 2 to 4 cm in diameter as well as a fifth plaque on the anterior portion of the right ankle that was approximately 6×6 cm. He denied fever, malaise, muscle weakness, changes in vision, or sensory deficits outside of the lesions themselves. The patient also denied any recent travel to endemic areas or exposure to armadillos.

Biopsies were taken from lesions on the lumbar back and anterior aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a granulomatous infiltrate spreading along neurovascular structures (Figure 2). Granulomas also were identified in the dermal interstitium exhibiting partial necrosis (Figure 2 inset). Conspicuous distension of lymphovascular and perineural areas also was noted. Immunohistochemical studies with S-100 and neurofilament stains allowed insight into the pathomechanism of the clinically observed anesthesia, as nerve fibers were identified showing different stages of damage elicited by the granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Fite staining was positive for occasional bacilli within histiocytes (Figure 3A inset). Despite the clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical evidence, the patient had no known exposure to leprosy; consequently, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was ordered for confirmation of the diagnosis. Surprisingly, the PCR was positive for Mycobacterium leprae DNA. These findings were consistent with borderline tuberculoid leprosy.

The case was reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program (Baton Rouge, Louisiana). The patient was started on rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The lesions exhibited marked improvement after completion of therapy (Figure 1B).

Comment

Disease Transmission

Hansen disease, also known as leprosy, is a chronic granulomatous infectious disease that is caused by M leprae, an obligate intracellular bacillus aerobe.1 The mechanism of spread of M leprae is not clear. It is thought to be transmitted via respiratory droplets, though it may occur through injured skin.2 Studies have suggested that in addition to humans, nine-banded armadillos are a source of infection.2,3 Exposure to infected individuals, particularly multibacillary patients, increases the likelihood of contracting leprosy.2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 81 cases of Hansen disease were diagnosed in the United States in 2013,4 compared to 178 cases registered in 2015.5 Cases from Hawaii, Texas, California, Louisiana, New York, and Florida made up 72% (129/178) of the reported cases. There was an increase from 34 cases to 49 cases in Florida from 2014 to 2015.5 The spread of leprosy throughout Florida may be from the merge of 2 armadillo populations, an M leprae–infected population migrating east from Texas and one from south central Florida that historically had not been infected with M leprae until recently.3,6 Our patient did not have any known exposures to armadillos.

Classification and Presentation

The clinical presentation of Hansen disease is widely variable, as it can present at any point along a spectrum ranging from tuberculoid leprosy to lepromatous leprosy with borderline conditions in between, according to the Ridley-Jopling critera.7 The World Health Organization also classifies leprosy based on the number of acid-fast bacilli seen in a skin smear as either paucibacillary or multibacillary.2 The paucibacillary classification correlates with tuberculoid, borderline tuberculoid, and indeterminate leprosy, and multibacillary correlates with borderline lepromatous and lepromatous leprosy. Paucibacillary leprosy usually presents with a less dramatic clinical picture than multibacillary leprosy. The clinical presentation is dependent on the magnitude of immune response to M leprae.2

Paucibacillary infection occurs when the body generates a strong cell-mediated immune response against the bacteria,8 which causes the activation and proliferation of CD4 and CD8 T cells, limiting the spread of the mycobacterium. Subsequently, the patient typically presents with a mild clinical picture with few skin lesions and limited nerve involvement.8 The skin lesions are papules or plaques with raised borders that are usually hypopigmented on dark skin and erythematous on light skin. Nerve involvement in paucibacillary forms of leprosy include sensory impairment and anhidrosis within the lesions. Nerve enlargement usually affects superficial nerves, with the posterior tibial nerve being most commonly affected.

Multibacillary leprosy presents with systemic involvement due to a weak cell-mediated immune response. Patients generally present with diffuse, poorly defined nodules; greater nerve impairment; and other systemic symptoms such as blindness, swelling of the fingers and toes, and testicular atrophy (in men). Additionally, enlargement of the earlobes and widening of the nasal bridge may contribute to the appearance of leonine facies. Nerve impairment in multibacillary forms of leprosy may be more severe, including more diffuse sensory involvement (eg, stocking glove–pattern neuropathy, nerve-trunk palsies), which ultimately may lead to foot drop, claw toe, and lagophthalmos.8

In addition to the clinical presentation, the histology of the paucibacillary and multibacillary types differ. Multibacillary leprosy shows diffuse histiocytes without granulomas and multiple bacilli seen on Fite staining.8 In the paucibacillary form, there are well-formed granulomas with Langerhans giant cells and a perineural lymphocytic infiltrate seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining with rare acid-fast bacilli seen on Fite staining.

To diagnose leprosy, at least one of the following 3 clinical signs must be present: (1) a hypopigmented or erythematous lesion with loss of sensation, (2) thickened peripheral nerve, or (3) acid-fast bacilli on slit-skin smear.2

Management

The World Health Organization guidelines involve multidrug therapy over an extended period of time.2 For adults, the paucibacillary regimen includes rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 6 months. The adult regimen for multibacillary leprosy includes clofazimine 300 mg once monthly and 50 mg once daily, in addition to rifampicin 600 mg once monthly and dapsone 100 mg once daily for 12 months. If classification cannot be determined, it is recommended the patient be treated for multibacillary disease.2

Reversal Reactions

During the course of the disease, patients may upgrade (to a less severe form) or downgrade (to a more severe form) between the tuberculoid, borderline, and lepromatous forms.8 The patient’s clinical picture also may change with complications of leprosy, which include type 1 and type 2 reactions. Type 1 reaction is a reversal reaction seen in 15% to 30% of patients at risk, usually those with borderline forms of leprosy.9 Reversal reactions usually manifest as erythema and edema of current skin lesions, formation of new tumid lesions, and tenderness of peripheral nerves with loss of nerve function.8 Treatment of reversal reactions involves systemic corticosteroids.10 Type 2 reaction is classified as erythema nodosum leprosum. It presents within the first 2 years of treatment in approximately 20% of lepromatous patients and approximately 10% of borderline lepromatous patients but is rare in paucibacillary infections.11 It presents with fever and crops of pink nodules and may include iritis, neuritis, lymphadenitis, orchitis, dactylitis, arthritis, and proteinuria.8 Treatment options for erythema nodosum leprosum include corticosteroids, clofazimine, and thalidomide.12,13

Conclusion

Hansen disease is a rare condition in the United States. This case is unique because, to our knowledge, it is the first known PCR-confirmed case of Hansen disease in Okeechobee County, Florida. Additionally, the patient had no known exposure to M leprae. Exposure is increasing due to the increased geographical range of infected armadillos. Infection rates also may rise due to travel to endemic countries. Initially lesions may appear as innocuous erythematous plaques. When they do not respond to standard therapy, infectious agents such as M leprae should be part of the differential diagnosis. Because hematoxylin and eosin staining does not always yield results, if clinical suspicion is present, PCR should be performed. If a patient meets the clinical and histological diagnosis, the case should be reported to the National Hansen’s Disease Program.

After completion of treatment, our patient has shown excellent results. He has not yet demonstrated a reversal reaction; however, he may still be at risk, as it most commonly presents 2 months after starting treatment but can present years after treatment has been initiated.8 Cutaneous leprosy must be considered in the differential diagnosis for steroid-nonresponsive skin lesions, particularly in states such as Florida with a documented increase in incidence.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sharon Barrineau, ARNP (Okeechobee, Florida), for her acumen, contributions, and support on this case.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, 8th Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Truman RW, Singh P, Sharma R, et al. Probable zoonotic leprosy in the southern United States. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1626-1633.

- Adams DA, Fullerton K, Jajosky R, et al; Division of Notifiable Diseases and Healthcare Information, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC. Summary of notifiable diseases—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;62:1-122.

- A summary of Hansen’s disease in the United States—2015. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Hansen’s Disease Program. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hansensdisease/pdfs/hansens2015report.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- Loughry WJ, Truman RW, McDonough CM, et al. Is leprosy spreading among nine-banded armadillos in the southeastern United States? J Wildl Dis. 2009;45:144-152.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five group system. Int J Lepr. 1966;34:225-273.

- Lee DJ, Rea TH, Modlin RL. Leprosy. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, et al. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:338-381.

- Britton WJ. The management of leprosy reversal reactions. Lepr Rev. 1998;69:225-234.

- Manandhar R, LeMaster JW, Roche PW. Risk factors for erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1999;67:270-278.

- Lockwood DN. The management of erythema nodosum leprosum: current and future options. Lepr Rev. 1996;67:253-259.

- Jakeman P, Smith WC. Thalidomide in leprosy reaction. Lancet. 1994;343:432-433.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, 8th Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Truman RW, Singh P, Sharma R, et al. Probable zoonotic leprosy in the southern United States. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1626-1633.

- Adams DA, Fullerton K, Jajosky R, et al; Division of Notifiable Diseases and Healthcare Information, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC. Summary of notifiable diseases—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;62:1-122.

- A summary of Hansen’s disease in the United States—2015. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Hansen’s Disease Program. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hansensdisease/pdfs/hansens2015report.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- Loughry WJ, Truman RW, McDonough CM, et al. Is leprosy spreading among nine-banded armadillos in the southeastern United States? J Wildl Dis. 2009;45:144-152.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five group system. Int J Lepr. 1966;34:225-273.

- Lee DJ, Rea TH, Modlin RL. Leprosy. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, et al. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:338-381.

- Britton WJ. The management of leprosy reversal reactions. Lepr Rev. 1998;69:225-234.

- Manandhar R, LeMaster JW, Roche PW. Risk factors for erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1999;67:270-278.

- Lockwood DN. The management of erythema nodosum leprosum: current and future options. Lepr Rev. 1996;67:253-259.

- Jakeman P, Smith WC. Thalidomide in leprosy reaction. Lancet. 1994;343:432-433.

Practice Points

- A majority of leprosy cases in the United States have been reported in Florida, California, Texas, Louisiana, Hawaii, and New York.

- Leprosy should be included in the differential diagnosis for annular plaques, particularly those not responding to traditional treatment.