User login

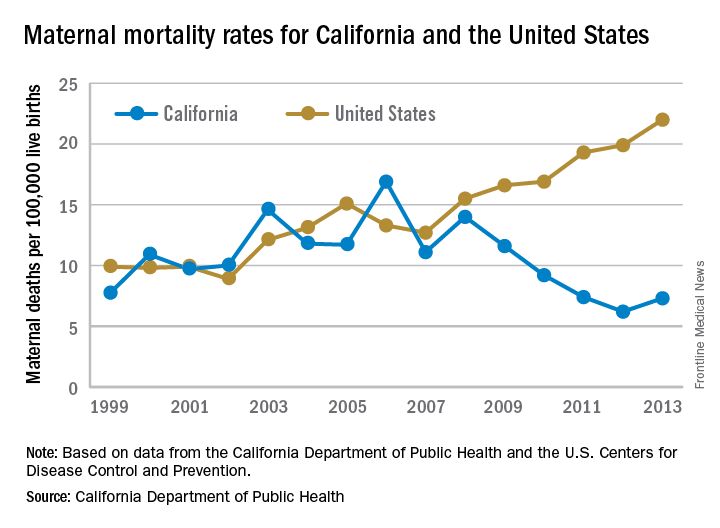

While the United States as a whole is seeing an unsettling rise in maternal mortality, California is on a divergent path.

Maternal mortality in the Golden State was tracking at a similar rate with national figures from 1999-2008 when the trend started to change. By 2013, the U.S. maternal mortality rate had grown to 22.0 deaths per 100,000 live births, while California’s rate had dropped to 7.3 per 100,000, according to data from the California Department of Public Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We reviewed every maternal death for almost 10 years and through that process, we learned a lot about practices of care and the opportunities to really have intervened,” Elliott Main, MD, medical director of the Collaborative, said in an interview. “There were certain causes of death that had a pretty high chance of preventability and those were hemorrhage and preeclampsia.”

Identifying risk factors

The Collaborative’s research identified a number of risk factors that were significant contributors to maternal morbidity.

Dr. Main noted that obesity and older maternal age are both associated with an increased likelihood of having a cesarean delivery, which is associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage.

“So there are pathways that can get you into more trouble, but again if you are on top of those, you can be proactive and not necessarily have this high rate of complications,” he added.

With data in hand about what was contributing to the risks of maternal mortality, the Collaborative set out to build a series of toolkits or “bundles” to help guide hospitals in limiting complications and responding to emergencies. These toolkits are based on the state’s own data, as well as best practices identified in the medical literature and national guidelines from organizations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

For example, the hypertension bundle includes information aimed at readiness, recognition and prevention, response, and reporting/system learning. Other bundles, which the Collaborative helped to develop and which are distributed through the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care, cover areas such as mental health, thromboembolism, hemorrhage, and safe reduction in primary cesarean births.

“It’s all about the implementation of those and that’s where we spent a lot of time in California with what are called quality collaboratives,” he said. “These are generally state-based [efforts], where you put together a consortium of providers, hospitals, and public health and patient advocates, and you work on improving the care for these certain conditions.”

The bundles are not meant to be cookbook medicine, Dr. Main noted, but rather are designed so that they can be customized based on the resources of an individual hospital, whether the facility handles 300 births a year or 5,000.

“There is no such thing as a national protocol for this,” Dr. Main said. “You have to have some flexibility and differences in the protocols but what we really are striving for is that for emergencies, people have standard protocols for the treatment of that emergency.”

Disparities remain

While California is a success story in terms of its overall drop in maternal mortality, racial disparities remain, particularly for African American women.

Maternal mortality among African Americans has dropped 50% in the state, mirroring the overall decline in the state during the 2008-2013 time period, but it is still three to four times higher than for other racial/ethnic groups.

“African American women do have more risk factors. There is more obesity. There is more hypertension and they have more social stresses and so forth, but none of those are reasons that they should die,” Dr. Main said. “They are reasons that they should have more intensive attention and care. If you have an older African American woman with hypertension, you’ve got to be on your toes when you are taking care of her and be a lot more responsive to warning signs than in a 25-year-old white woman that is perfectly healthy.”

“Minorities represent half of all U.S. persons, yet racial and ethnic minorities suffer higher rates of maternal mortality than whites in this country,” said Dr. Howell, who also chairs ACOG’s work group on reduction of peripartum racial disparities. “In fact, black and African Americans are three to four times more likely to die than whites. This is the largest disparity among population perinatal health measures.”

Native Americans, Asians, and some Latinas also have elevated rates of maternal mortality, compared with white women, she noted.

Depending on the city, those rates could be even higher, she said.

“In New York City, a recent publication by our Department of Health reviewed deaths from 2006 to 2010 and they found that black women were 10 times more likely to die than white women,” Dr. Howell said. “It’s also important to remember that for every maternal death, over 100 women experience severe obstetric morbidity or a life-threatening diagnosis or undergo a lifesaving procedure during their delivery hospitalization.”

But there are care tools available to help address this issue, too. The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health, which includes the California collaborative and ACOG, has developed a safety bundle that focuses on themes of shared decision making, implicit bias, continuity of care, provider and patient education, and care fragmentation. It also recommends implementation of a disparity dashboard, meaning that hospitals and health systems would stratify their quality results by race and ethnicity to identify and address gaps in care, Dr. Howell said.

gtwachtman@frontlinemedcom.com

While the United States as a whole is seeing an unsettling rise in maternal mortality, California is on a divergent path.

Maternal mortality in the Golden State was tracking at a similar rate with national figures from 1999-2008 when the trend started to change. By 2013, the U.S. maternal mortality rate had grown to 22.0 deaths per 100,000 live births, while California’s rate had dropped to 7.3 per 100,000, according to data from the California Department of Public Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We reviewed every maternal death for almost 10 years and through that process, we learned a lot about practices of care and the opportunities to really have intervened,” Elliott Main, MD, medical director of the Collaborative, said in an interview. “There were certain causes of death that had a pretty high chance of preventability and those were hemorrhage and preeclampsia.”

Identifying risk factors

The Collaborative’s research identified a number of risk factors that were significant contributors to maternal morbidity.

Dr. Main noted that obesity and older maternal age are both associated with an increased likelihood of having a cesarean delivery, which is associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage.

“So there are pathways that can get you into more trouble, but again if you are on top of those, you can be proactive and not necessarily have this high rate of complications,” he added.

With data in hand about what was contributing to the risks of maternal mortality, the Collaborative set out to build a series of toolkits or “bundles” to help guide hospitals in limiting complications and responding to emergencies. These toolkits are based on the state’s own data, as well as best practices identified in the medical literature and national guidelines from organizations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

For example, the hypertension bundle includes information aimed at readiness, recognition and prevention, response, and reporting/system learning. Other bundles, which the Collaborative helped to develop and which are distributed through the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care, cover areas such as mental health, thromboembolism, hemorrhage, and safe reduction in primary cesarean births.

“It’s all about the implementation of those and that’s where we spent a lot of time in California with what are called quality collaboratives,” he said. “These are generally state-based [efforts], where you put together a consortium of providers, hospitals, and public health and patient advocates, and you work on improving the care for these certain conditions.”

The bundles are not meant to be cookbook medicine, Dr. Main noted, but rather are designed so that they can be customized based on the resources of an individual hospital, whether the facility handles 300 births a year or 5,000.

“There is no such thing as a national protocol for this,” Dr. Main said. “You have to have some flexibility and differences in the protocols but what we really are striving for is that for emergencies, people have standard protocols for the treatment of that emergency.”

Disparities remain

While California is a success story in terms of its overall drop in maternal mortality, racial disparities remain, particularly for African American women.

Maternal mortality among African Americans has dropped 50% in the state, mirroring the overall decline in the state during the 2008-2013 time period, but it is still three to four times higher than for other racial/ethnic groups.

“African American women do have more risk factors. There is more obesity. There is more hypertension and they have more social stresses and so forth, but none of those are reasons that they should die,” Dr. Main said. “They are reasons that they should have more intensive attention and care. If you have an older African American woman with hypertension, you’ve got to be on your toes when you are taking care of her and be a lot more responsive to warning signs than in a 25-year-old white woman that is perfectly healthy.”

“Minorities represent half of all U.S. persons, yet racial and ethnic minorities suffer higher rates of maternal mortality than whites in this country,” said Dr. Howell, who also chairs ACOG’s work group on reduction of peripartum racial disparities. “In fact, black and African Americans are three to four times more likely to die than whites. This is the largest disparity among population perinatal health measures.”

Native Americans, Asians, and some Latinas also have elevated rates of maternal mortality, compared with white women, she noted.

Depending on the city, those rates could be even higher, she said.

“In New York City, a recent publication by our Department of Health reviewed deaths from 2006 to 2010 and they found that black women were 10 times more likely to die than white women,” Dr. Howell said. “It’s also important to remember that for every maternal death, over 100 women experience severe obstetric morbidity or a life-threatening diagnosis or undergo a lifesaving procedure during their delivery hospitalization.”

But there are care tools available to help address this issue, too. The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health, which includes the California collaborative and ACOG, has developed a safety bundle that focuses on themes of shared decision making, implicit bias, continuity of care, provider and patient education, and care fragmentation. It also recommends implementation of a disparity dashboard, meaning that hospitals and health systems would stratify their quality results by race and ethnicity to identify and address gaps in care, Dr. Howell said.

gtwachtman@frontlinemedcom.com

While the United States as a whole is seeing an unsettling rise in maternal mortality, California is on a divergent path.

Maternal mortality in the Golden State was tracking at a similar rate with national figures from 1999-2008 when the trend started to change. By 2013, the U.S. maternal mortality rate had grown to 22.0 deaths per 100,000 live births, while California’s rate had dropped to 7.3 per 100,000, according to data from the California Department of Public Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We reviewed every maternal death for almost 10 years and through that process, we learned a lot about practices of care and the opportunities to really have intervened,” Elliott Main, MD, medical director of the Collaborative, said in an interview. “There were certain causes of death that had a pretty high chance of preventability and those were hemorrhage and preeclampsia.”

Identifying risk factors

The Collaborative’s research identified a number of risk factors that were significant contributors to maternal morbidity.

Dr. Main noted that obesity and older maternal age are both associated with an increased likelihood of having a cesarean delivery, which is associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage.

“So there are pathways that can get you into more trouble, but again if you are on top of those, you can be proactive and not necessarily have this high rate of complications,” he added.

With data in hand about what was contributing to the risks of maternal mortality, the Collaborative set out to build a series of toolkits or “bundles” to help guide hospitals in limiting complications and responding to emergencies. These toolkits are based on the state’s own data, as well as best practices identified in the medical literature and national guidelines from organizations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

For example, the hypertension bundle includes information aimed at readiness, recognition and prevention, response, and reporting/system learning. Other bundles, which the Collaborative helped to develop and which are distributed through the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care, cover areas such as mental health, thromboembolism, hemorrhage, and safe reduction in primary cesarean births.

“It’s all about the implementation of those and that’s where we spent a lot of time in California with what are called quality collaboratives,” he said. “These are generally state-based [efforts], where you put together a consortium of providers, hospitals, and public health and patient advocates, and you work on improving the care for these certain conditions.”

The bundles are not meant to be cookbook medicine, Dr. Main noted, but rather are designed so that they can be customized based on the resources of an individual hospital, whether the facility handles 300 births a year or 5,000.

“There is no such thing as a national protocol for this,” Dr. Main said. “You have to have some flexibility and differences in the protocols but what we really are striving for is that for emergencies, people have standard protocols for the treatment of that emergency.”

Disparities remain

While California is a success story in terms of its overall drop in maternal mortality, racial disparities remain, particularly for African American women.

Maternal mortality among African Americans has dropped 50% in the state, mirroring the overall decline in the state during the 2008-2013 time period, but it is still three to four times higher than for other racial/ethnic groups.

“African American women do have more risk factors. There is more obesity. There is more hypertension and they have more social stresses and so forth, but none of those are reasons that they should die,” Dr. Main said. “They are reasons that they should have more intensive attention and care. If you have an older African American woman with hypertension, you’ve got to be on your toes when you are taking care of her and be a lot more responsive to warning signs than in a 25-year-old white woman that is perfectly healthy.”

“Minorities represent half of all U.S. persons, yet racial and ethnic minorities suffer higher rates of maternal mortality than whites in this country,” said Dr. Howell, who also chairs ACOG’s work group on reduction of peripartum racial disparities. “In fact, black and African Americans are three to four times more likely to die than whites. This is the largest disparity among population perinatal health measures.”

Native Americans, Asians, and some Latinas also have elevated rates of maternal mortality, compared with white women, she noted.

Depending on the city, those rates could be even higher, she said.

“In New York City, a recent publication by our Department of Health reviewed deaths from 2006 to 2010 and they found that black women were 10 times more likely to die than white women,” Dr. Howell said. “It’s also important to remember that for every maternal death, over 100 women experience severe obstetric morbidity or a life-threatening diagnosis or undergo a lifesaving procedure during their delivery hospitalization.”

But there are care tools available to help address this issue, too. The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health, which includes the California collaborative and ACOG, has developed a safety bundle that focuses on themes of shared decision making, implicit bias, continuity of care, provider and patient education, and care fragmentation. It also recommends implementation of a disparity dashboard, meaning that hospitals and health systems would stratify their quality results by race and ethnicity to identify and address gaps in care, Dr. Howell said.

gtwachtman@frontlinemedcom.com