User login

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

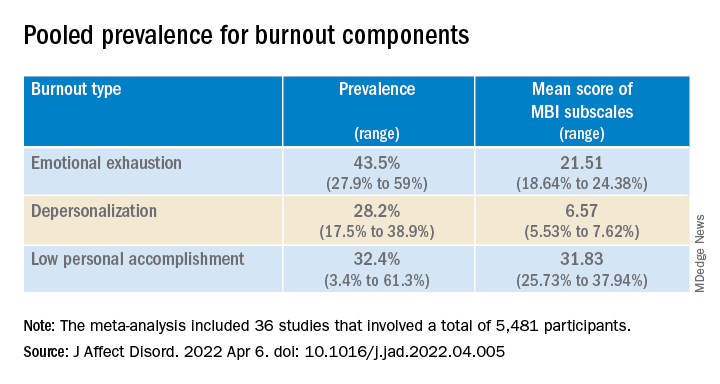

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

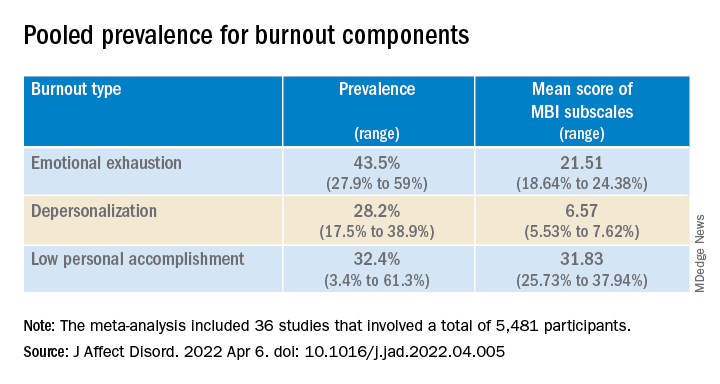

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

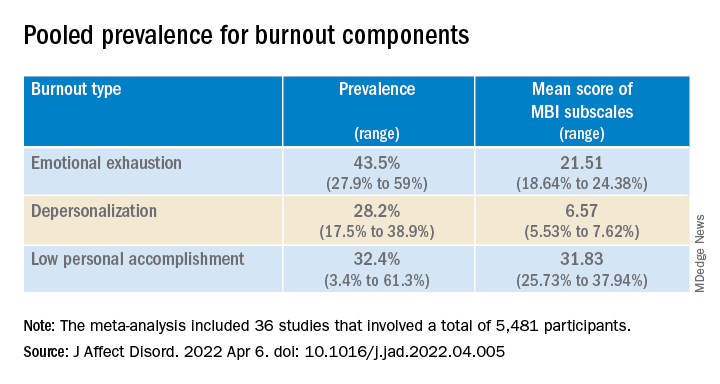

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS