User login

Autoimmune bullous dermatoses (ABDs) develop due to antibodies directed against antigens within the epidermis or at the dermoepidermal junction. They are categorized histologically by the location of acantholysis (separation of keratinocytes), clinical presentation, and presence of autoantibodies. The most common ABDs include pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid (BP). These conditions present on a spectrum of symptoms and severity.1

Although multiple studies have evaluated the impact of bullous dermatoses on mental health, most were designed with a small sample size, thus limiting the generalizability of each study. Sebaratnam et al2 summarized several studies in 2012. In this review, we will analyze additional relevant literature and systematically combine the data to determine the psychological burden of disease of ABDs. We also will discuss the existing questionnaires frequently used in the dermatology setting to assess adverse psychosocial symptoms.

Methods

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar for articles published within the last 15 years using the terms bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus, quality of life, anxiety, and depression. We reviewed the citations in each article to further our search.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion—Studies that utilized validated questionnaires to evaluate the effects of pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and/or BP on mental health were included. All research participants were 18 years and older. For the questionnaires administered, each study must have included numerical scores in the results. The studies all reported statistically significant results (P<.05), but no studies were excluded on the basis of statistical significance.

Studies were excluded if they did not use a validated questionnaire to examine quality of life (QOL) or psychological status. We also excluded database, retrospective, qualitative, and observational studies. We did not include studies with a sample size less than 20. Studies that administered questionnaires that were uncommon in this realm of research such as the Attitude to Appearance Scale or The Anxiety Questionnaire also were excluded. We did not exclude articles based on their primary language.

Results

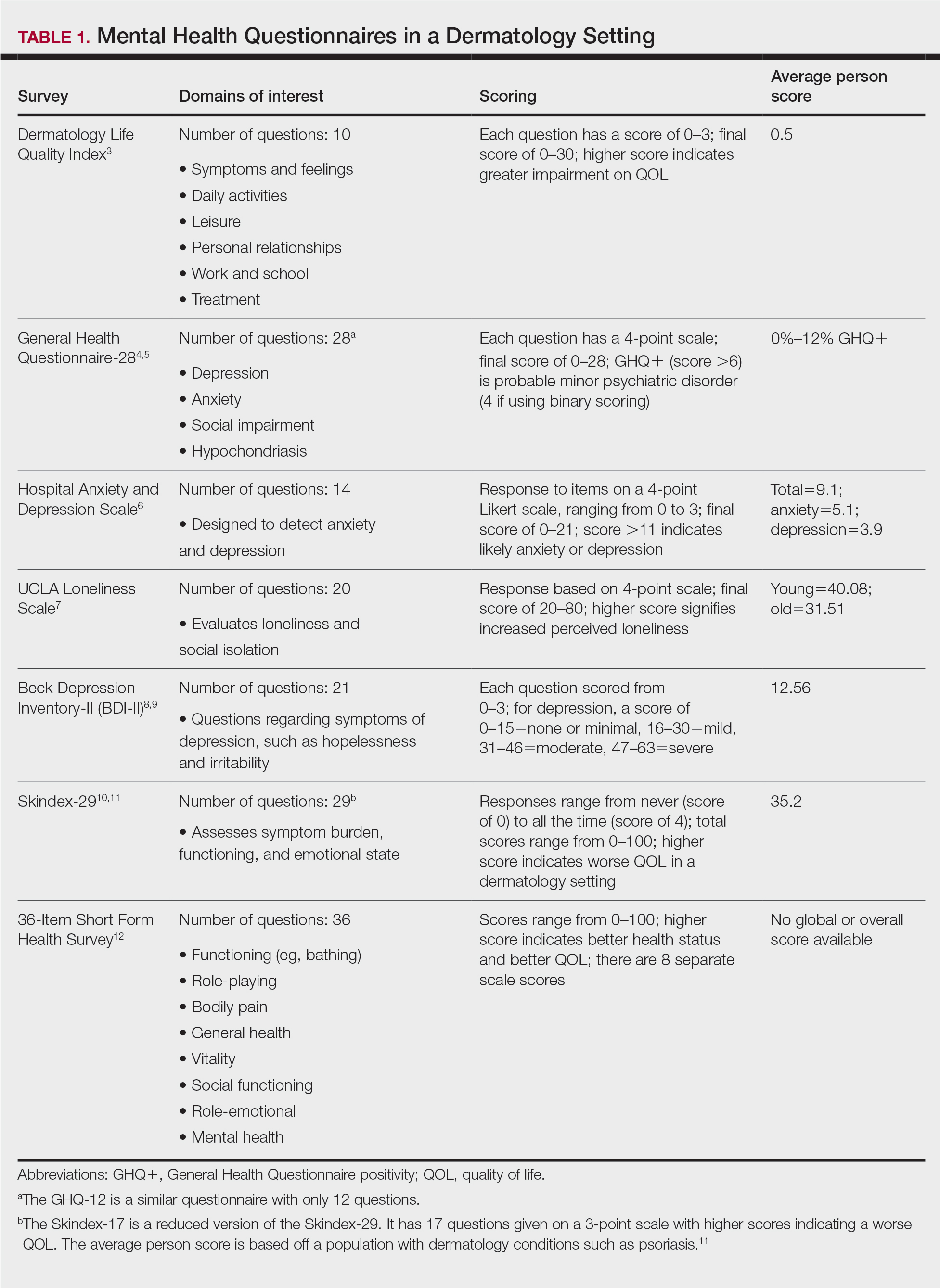

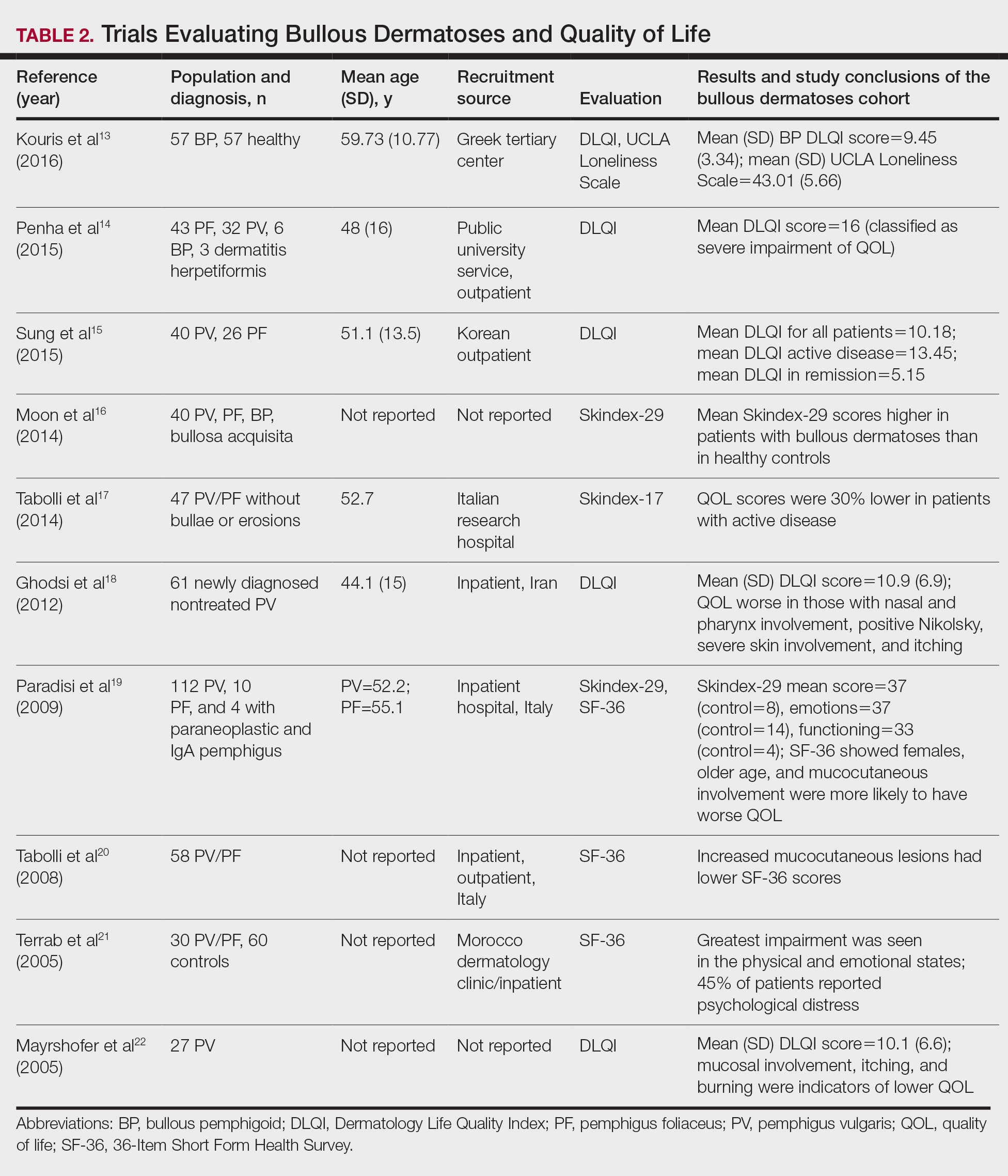

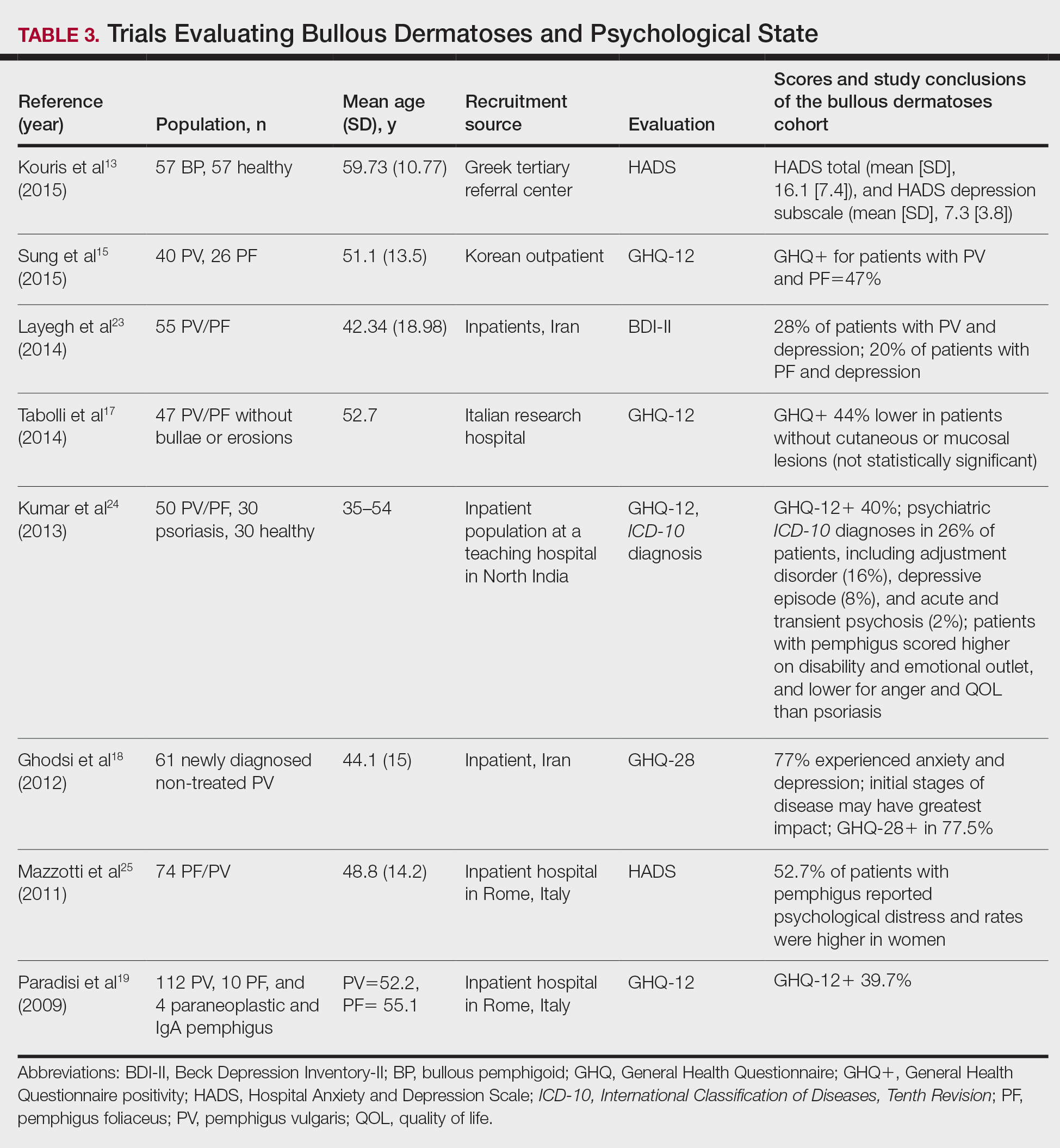

A total of 13 studies met the inclusion criteria with a total of 1716 participants enrolled in the trials. The questionnaires most commonly used are summarized in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate the studies that evaluate QOL and psychological state in patients with bullous dermatoses, respectively.

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was the most utilized method for analyzing QOL followed by the Skindex-17, Skindex-29, and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey. The DLQI is a skin-specific measurement tool with higher scores translating to greater impairment in QOL. Healthy patients have an average score of 0.5.3 The mean DLQI scores for ABD patients as seen in Table 2 were 9.45, 10.18, 16, 10.9, and 10.1.13-15,18,22 The most commonly reported concerns among patients included feelings about appearance and disturbances in daily activities.18 Symptoms of mucosal involvement, itching, and burning also were indicators of lower QOL.15,18,20,22 Furthermore, women consistently had lower scores than men.15,17,19,25 Multiple studies concluded that severity of the disease correlated with a lower QOL, though the subtype of pemphigus did not have an effect on QOL scores.15,19,20,21 Lastly, recent onset of symptoms was associated with a worse QOL score.15,18-20 Age, education level, and marital status did not have an effect on QOL.

To evaluate psychological state, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-28 and -12 primarily were used, in addition to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; and the Beck Depression Inventory-II. As seen in Table 3, GHQ-12 positivity, reflecting probable minor nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, was identified in 47%, 39.7%, and 40% of patients with pemphigus15,19,24; GHQ-28 positivity was seen in 77.5% of pemphigus patients.18 In the average population, GHQ positivity was found in up to 12% of patients.26,27 Similar to the QOL scores, no significant differences were seen based on subtype of pemphigus for symptoms of depression or anxiety.20,23

Comment

Mental Health of Patients With ABDs—Immunobullous diseases are painful, potentially lifelong conditions that have no definitive cure. These conditions are characterized by bullae and erosions of the skin and mucosae that physically are disabling and often create a stigma for patients. Across multiple different validated psychosocial assessments, the 13 studies included in this review consistently reported that ABDs have a negative effect on mental well-being of patients that is more pronounced in women and worse at the onset of symptoms.13-25

QOL Scores in Patients With ABDs—Quality of life is a broad term that encompasses a general sense of psychological and overall well-being. A score of approximately 10 on the DLQI most often was reported in patients with ABDs, which translates to a moderate impact on QOL. Incomparison, a large cohort study reported the mean (SD) DLQI scores for patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis as 7.31 (5.98) and 5.93 (5.66), respectively.28 In another study, Penha et al14 found that patients with psoriasis have a mean DLQI score of 10. Reasons for the similarly low QOL scores in patients with ABDs include long hospitalization periods, disease chronicity, social anxiety, inability to control symptoms, difficulty with activities of daily living, and the belief that the disease is incurable.17,19,23 Although there is a need for increased family and social support with performing necessary daily tasks, personal relationships often are negatively affected, resulting in social isolation, loneliness, and worsening of cutaneous symptoms.

Severity of cutaneous disease and recent onset of symptoms correlated with worse QOL scores. Tabolli et al20 proposed the reason for this relates to not having had enough time to find the best treatment regimen. We believe there also may be an element of habituation involved, whereby patients become accustomed to the appearance of the lesions over time and therefore they become less distressing. Interestingly, Tabolli et al17 determined that patients in the quiescent phase of the disease—without any mucosal or cutaneous lesions—still maintained lower QOL scores than the average population, particularly on the psychosocial section of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, which may be due to a concern of disease relapse or from adverse effects of treatment. Providers should monitor patients for mental health complications not only in the disease infancy but throughout the disease course.

Future Directions—Cause and effect of the relationship between the psychosocial variables and ABD disease state has yet to be determined. Most studies included in this review were cross-sectional in design. Although many studies concluded that bullous dermatoses were the cause of impaired QOL, Ren and colleagues29 proposed that medications used to treat neuropsychiatric disorders may trigger the autoimmune antigens of BP. Possible triggers for BP have been reported including hydrochlorothiazide, ciprofloxacin, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.27,30-32 A longitudinal study design would better evaluate the causal relationship.

The effects of the medications were included in 2 cases, one in which the steroid dose was not found to have a significant impact on rates of depression23 and another in which patients treated with a higher dose of corticosteroids (>10 mg) had worse QOL scores.17 Sung et al15 suggested this may be because patients who took higher doses of steroids had worse symptoms and therefore also had a worse QOL. It also is possible that those patients taking higher doses had increased side effects.17 Further studies that evaluate treatment modalities and timing in relation to the disease onset would be helpful.

Study Limitations—There are potential barriers to combining these data. Multiple different questionnaires were used, and it was difficult to ascertain if all the participants were experiencing active disease. Additionally, questionnaires are not always the best proxy for what is happening in everyday life. Lastly, the sample size of each individual study was small, and the studies only included adults.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by the 13 studies in this review, patients with ABDs have lower QOL scores and higher numbers of psychological symptoms. Clinicians should be mindful of this at-risk population and create opportunities in clinic to discuss personal hardship associated with the disease process and recommend psychiatric intervention if indicated. Additionally, family members often are overburdened with the chronicity of ABDs, and they should not be forgotten. Using one of the aforementioned questionnaires is a practical way to screen patients for lower QOL scores. We agree with Paradisi and colleagues19 that although these questionnaires may be helpful, clinicians still need to determine if the use of a dermatologic QOL evaluation tool in clinical practice improves patient satisfaction.

- Baum S, Sakka N, Artsi O, et al. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune blistering diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:482-489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.047

- Sebaratnam DF, McMillan JR, Werth VP, et al. Quality of life in patients with bullous dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:103-107. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.016

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Goldberg DP. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. Oxford University Press; 1972.

- Cano A, Sprafkin RP, Scaturo DJ, et al. Mental health screening in primary care: a comparison of 3 brief measures of psychological distress. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:206-210.

- Zigmond A, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370.

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20-40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

- Beck A, Alford B. Depression: Causes and Treatment. 2nd ed. Philadelphia University of Pennsylvania Press; 2009.

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, et al. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:185-192. doi:10.1002/da.20070

- Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, et al. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105-110.

- Nijsten TEC, Sampogna F, Chren M, et al. Testing and reducing Skindex-29 using Rasch analysis: Skindex-17. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1244-1250. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700212

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

- Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, et al. Quality of life, depression, anxiety and loneliness in patients with bullous pemphigoid: a case control study. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:601-603. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.2016493

- Penha MA, Farat JG, Miot HA, et al. Quality of life index in autoimmune bullous dermatosis patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:190-194. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153372

- Sung JY, Roh MR, Kim SC. Quality of life assessment in Korean patients with pemphigus. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:492-498.

- Moon SH, Kwon HI, Park HC, et al. Assessment of the quality of life in autoimmune blistering skin disease patients. Korean J Dermatol. 2014;52:402-409.

- Tabolli S, Pagliarello C, Paradisi A, et al. Burden of disease during quiescent periods in patients with pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1087-1091. doi:10.1111/bjd.12836

- Ghodsi SZ, Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and general health questionnaires. J Dermatol. 2012;39:141-144. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01382

- Paradisi A, Sampogna F, Di Pietro C, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:261-269. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.014

- Tabolli S, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. The health impact of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1029-1034. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08481.x

- Terrab Z, Benchikhi H, Maaroufi A, et al. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-328.

- Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris: results from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431-435. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05722.x

- Layegh P, Mokhber N, Javidi Z, et al. Depression in patients with pemphigus: is it a major concern? J Dermatol. 2014;40:434-437. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12067

- Kumar V, Mattoo SK, Handa S. Psychiatric morbidity in pemphigus and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:151-156. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2012.10.005

- Mazzotti E, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. Psychological distress and investment in one’s appearance in patients with pemphigus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:285-289. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03780.x

- Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five epidemiologic catchment area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1988;45:977-986. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002

- Cozzani E, Chinazzo C, Burlando M, et al. Ciprofloxacin as a trigger for bullous pemphigoid: the second case in the literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:E1202-E1204. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000283

- Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Silverdahl M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis measured with SF-36, DLQI and a subjective measure of disease activity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:430-434.

- Ren Z, Hsu DY, Brieva J, et al. Hospitalization, inpatient burden and comorbidities associated with bullous pemphigoid in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:87-99. doi:10.1111/bjd.14821

- Warner C, Kwak Y, Glover MH, et al. Bullous pemphigoid induced by hydrochlorothiazide therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:360-362.

- Mendonca FM, Martin-Gutierrez FJ, Rios-Martin JJ, et al. Three cases of bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors—one due to linagliptin. Dermatology. 2016;232:249-253. doi:10.1159/000443330

- Attaway A, Mersfelder TL, Vaishnav S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors: a case report and review of literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:24-28.

Autoimmune bullous dermatoses (ABDs) develop due to antibodies directed against antigens within the epidermis or at the dermoepidermal junction. They are categorized histologically by the location of acantholysis (separation of keratinocytes), clinical presentation, and presence of autoantibodies. The most common ABDs include pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid (BP). These conditions present on a spectrum of symptoms and severity.1

Although multiple studies have evaluated the impact of bullous dermatoses on mental health, most were designed with a small sample size, thus limiting the generalizability of each study. Sebaratnam et al2 summarized several studies in 2012. In this review, we will analyze additional relevant literature and systematically combine the data to determine the psychological burden of disease of ABDs. We also will discuss the existing questionnaires frequently used in the dermatology setting to assess adverse psychosocial symptoms.

Methods

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar for articles published within the last 15 years using the terms bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus, quality of life, anxiety, and depression. We reviewed the citations in each article to further our search.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion—Studies that utilized validated questionnaires to evaluate the effects of pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and/or BP on mental health were included. All research participants were 18 years and older. For the questionnaires administered, each study must have included numerical scores in the results. The studies all reported statistically significant results (P<.05), but no studies were excluded on the basis of statistical significance.

Studies were excluded if they did not use a validated questionnaire to examine quality of life (QOL) or psychological status. We also excluded database, retrospective, qualitative, and observational studies. We did not include studies with a sample size less than 20. Studies that administered questionnaires that were uncommon in this realm of research such as the Attitude to Appearance Scale or The Anxiety Questionnaire also were excluded. We did not exclude articles based on their primary language.

Results

A total of 13 studies met the inclusion criteria with a total of 1716 participants enrolled in the trials. The questionnaires most commonly used are summarized in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate the studies that evaluate QOL and psychological state in patients with bullous dermatoses, respectively.

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was the most utilized method for analyzing QOL followed by the Skindex-17, Skindex-29, and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey. The DLQI is a skin-specific measurement tool with higher scores translating to greater impairment in QOL. Healthy patients have an average score of 0.5.3 The mean DLQI scores for ABD patients as seen in Table 2 were 9.45, 10.18, 16, 10.9, and 10.1.13-15,18,22 The most commonly reported concerns among patients included feelings about appearance and disturbances in daily activities.18 Symptoms of mucosal involvement, itching, and burning also were indicators of lower QOL.15,18,20,22 Furthermore, women consistently had lower scores than men.15,17,19,25 Multiple studies concluded that severity of the disease correlated with a lower QOL, though the subtype of pemphigus did not have an effect on QOL scores.15,19,20,21 Lastly, recent onset of symptoms was associated with a worse QOL score.15,18-20 Age, education level, and marital status did not have an effect on QOL.

To evaluate psychological state, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-28 and -12 primarily were used, in addition to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; and the Beck Depression Inventory-II. As seen in Table 3, GHQ-12 positivity, reflecting probable minor nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, was identified in 47%, 39.7%, and 40% of patients with pemphigus15,19,24; GHQ-28 positivity was seen in 77.5% of pemphigus patients.18 In the average population, GHQ positivity was found in up to 12% of patients.26,27 Similar to the QOL scores, no significant differences were seen based on subtype of pemphigus for symptoms of depression or anxiety.20,23

Comment

Mental Health of Patients With ABDs—Immunobullous diseases are painful, potentially lifelong conditions that have no definitive cure. These conditions are characterized by bullae and erosions of the skin and mucosae that physically are disabling and often create a stigma for patients. Across multiple different validated psychosocial assessments, the 13 studies included in this review consistently reported that ABDs have a negative effect on mental well-being of patients that is more pronounced in women and worse at the onset of symptoms.13-25

QOL Scores in Patients With ABDs—Quality of life is a broad term that encompasses a general sense of psychological and overall well-being. A score of approximately 10 on the DLQI most often was reported in patients with ABDs, which translates to a moderate impact on QOL. Incomparison, a large cohort study reported the mean (SD) DLQI scores for patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis as 7.31 (5.98) and 5.93 (5.66), respectively.28 In another study, Penha et al14 found that patients with psoriasis have a mean DLQI score of 10. Reasons for the similarly low QOL scores in patients with ABDs include long hospitalization periods, disease chronicity, social anxiety, inability to control symptoms, difficulty with activities of daily living, and the belief that the disease is incurable.17,19,23 Although there is a need for increased family and social support with performing necessary daily tasks, personal relationships often are negatively affected, resulting in social isolation, loneliness, and worsening of cutaneous symptoms.

Severity of cutaneous disease and recent onset of symptoms correlated with worse QOL scores. Tabolli et al20 proposed the reason for this relates to not having had enough time to find the best treatment regimen. We believe there also may be an element of habituation involved, whereby patients become accustomed to the appearance of the lesions over time and therefore they become less distressing. Interestingly, Tabolli et al17 determined that patients in the quiescent phase of the disease—without any mucosal or cutaneous lesions—still maintained lower QOL scores than the average population, particularly on the psychosocial section of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, which may be due to a concern of disease relapse or from adverse effects of treatment. Providers should monitor patients for mental health complications not only in the disease infancy but throughout the disease course.

Future Directions—Cause and effect of the relationship between the psychosocial variables and ABD disease state has yet to be determined. Most studies included in this review were cross-sectional in design. Although many studies concluded that bullous dermatoses were the cause of impaired QOL, Ren and colleagues29 proposed that medications used to treat neuropsychiatric disorders may trigger the autoimmune antigens of BP. Possible triggers for BP have been reported including hydrochlorothiazide, ciprofloxacin, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.27,30-32 A longitudinal study design would better evaluate the causal relationship.

The effects of the medications were included in 2 cases, one in which the steroid dose was not found to have a significant impact on rates of depression23 and another in which patients treated with a higher dose of corticosteroids (>10 mg) had worse QOL scores.17 Sung et al15 suggested this may be because patients who took higher doses of steroids had worse symptoms and therefore also had a worse QOL. It also is possible that those patients taking higher doses had increased side effects.17 Further studies that evaluate treatment modalities and timing in relation to the disease onset would be helpful.

Study Limitations—There are potential barriers to combining these data. Multiple different questionnaires were used, and it was difficult to ascertain if all the participants were experiencing active disease. Additionally, questionnaires are not always the best proxy for what is happening in everyday life. Lastly, the sample size of each individual study was small, and the studies only included adults.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by the 13 studies in this review, patients with ABDs have lower QOL scores and higher numbers of psychological symptoms. Clinicians should be mindful of this at-risk population and create opportunities in clinic to discuss personal hardship associated with the disease process and recommend psychiatric intervention if indicated. Additionally, family members often are overburdened with the chronicity of ABDs, and they should not be forgotten. Using one of the aforementioned questionnaires is a practical way to screen patients for lower QOL scores. We agree with Paradisi and colleagues19 that although these questionnaires may be helpful, clinicians still need to determine if the use of a dermatologic QOL evaluation tool in clinical practice improves patient satisfaction.

Autoimmune bullous dermatoses (ABDs) develop due to antibodies directed against antigens within the epidermis or at the dermoepidermal junction. They are categorized histologically by the location of acantholysis (separation of keratinocytes), clinical presentation, and presence of autoantibodies. The most common ABDs include pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid (BP). These conditions present on a spectrum of symptoms and severity.1

Although multiple studies have evaluated the impact of bullous dermatoses on mental health, most were designed with a small sample size, thus limiting the generalizability of each study. Sebaratnam et al2 summarized several studies in 2012. In this review, we will analyze additional relevant literature and systematically combine the data to determine the psychological burden of disease of ABDs. We also will discuss the existing questionnaires frequently used in the dermatology setting to assess adverse psychosocial symptoms.

Methods

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar for articles published within the last 15 years using the terms bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus, quality of life, anxiety, and depression. We reviewed the citations in each article to further our search.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion—Studies that utilized validated questionnaires to evaluate the effects of pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and/or BP on mental health were included. All research participants were 18 years and older. For the questionnaires administered, each study must have included numerical scores in the results. The studies all reported statistically significant results (P<.05), but no studies were excluded on the basis of statistical significance.

Studies were excluded if they did not use a validated questionnaire to examine quality of life (QOL) or psychological status. We also excluded database, retrospective, qualitative, and observational studies. We did not include studies with a sample size less than 20. Studies that administered questionnaires that were uncommon in this realm of research such as the Attitude to Appearance Scale or The Anxiety Questionnaire also were excluded. We did not exclude articles based on their primary language.

Results

A total of 13 studies met the inclusion criteria with a total of 1716 participants enrolled in the trials. The questionnaires most commonly used are summarized in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate the studies that evaluate QOL and psychological state in patients with bullous dermatoses, respectively.

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was the most utilized method for analyzing QOL followed by the Skindex-17, Skindex-29, and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey. The DLQI is a skin-specific measurement tool with higher scores translating to greater impairment in QOL. Healthy patients have an average score of 0.5.3 The mean DLQI scores for ABD patients as seen in Table 2 were 9.45, 10.18, 16, 10.9, and 10.1.13-15,18,22 The most commonly reported concerns among patients included feelings about appearance and disturbances in daily activities.18 Symptoms of mucosal involvement, itching, and burning also were indicators of lower QOL.15,18,20,22 Furthermore, women consistently had lower scores than men.15,17,19,25 Multiple studies concluded that severity of the disease correlated with a lower QOL, though the subtype of pemphigus did not have an effect on QOL scores.15,19,20,21 Lastly, recent onset of symptoms was associated with a worse QOL score.15,18-20 Age, education level, and marital status did not have an effect on QOL.

To evaluate psychological state, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-28 and -12 primarily were used, in addition to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; and the Beck Depression Inventory-II. As seen in Table 3, GHQ-12 positivity, reflecting probable minor nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, was identified in 47%, 39.7%, and 40% of patients with pemphigus15,19,24; GHQ-28 positivity was seen in 77.5% of pemphigus patients.18 In the average population, GHQ positivity was found in up to 12% of patients.26,27 Similar to the QOL scores, no significant differences were seen based on subtype of pemphigus for symptoms of depression or anxiety.20,23

Comment

Mental Health of Patients With ABDs—Immunobullous diseases are painful, potentially lifelong conditions that have no definitive cure. These conditions are characterized by bullae and erosions of the skin and mucosae that physically are disabling and often create a stigma for patients. Across multiple different validated psychosocial assessments, the 13 studies included in this review consistently reported that ABDs have a negative effect on mental well-being of patients that is more pronounced in women and worse at the onset of symptoms.13-25

QOL Scores in Patients With ABDs—Quality of life is a broad term that encompasses a general sense of psychological and overall well-being. A score of approximately 10 on the DLQI most often was reported in patients with ABDs, which translates to a moderate impact on QOL. Incomparison, a large cohort study reported the mean (SD) DLQI scores for patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis as 7.31 (5.98) and 5.93 (5.66), respectively.28 In another study, Penha et al14 found that patients with psoriasis have a mean DLQI score of 10. Reasons for the similarly low QOL scores in patients with ABDs include long hospitalization periods, disease chronicity, social anxiety, inability to control symptoms, difficulty with activities of daily living, and the belief that the disease is incurable.17,19,23 Although there is a need for increased family and social support with performing necessary daily tasks, personal relationships often are negatively affected, resulting in social isolation, loneliness, and worsening of cutaneous symptoms.

Severity of cutaneous disease and recent onset of symptoms correlated with worse QOL scores. Tabolli et al20 proposed the reason for this relates to not having had enough time to find the best treatment regimen. We believe there also may be an element of habituation involved, whereby patients become accustomed to the appearance of the lesions over time and therefore they become less distressing. Interestingly, Tabolli et al17 determined that patients in the quiescent phase of the disease—without any mucosal or cutaneous lesions—still maintained lower QOL scores than the average population, particularly on the psychosocial section of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, which may be due to a concern of disease relapse or from adverse effects of treatment. Providers should monitor patients for mental health complications not only in the disease infancy but throughout the disease course.

Future Directions—Cause and effect of the relationship between the psychosocial variables and ABD disease state has yet to be determined. Most studies included in this review were cross-sectional in design. Although many studies concluded that bullous dermatoses were the cause of impaired QOL, Ren and colleagues29 proposed that medications used to treat neuropsychiatric disorders may trigger the autoimmune antigens of BP. Possible triggers for BP have been reported including hydrochlorothiazide, ciprofloxacin, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.27,30-32 A longitudinal study design would better evaluate the causal relationship.

The effects of the medications were included in 2 cases, one in which the steroid dose was not found to have a significant impact on rates of depression23 and another in which patients treated with a higher dose of corticosteroids (>10 mg) had worse QOL scores.17 Sung et al15 suggested this may be because patients who took higher doses of steroids had worse symptoms and therefore also had a worse QOL. It also is possible that those patients taking higher doses had increased side effects.17 Further studies that evaluate treatment modalities and timing in relation to the disease onset would be helpful.

Study Limitations—There are potential barriers to combining these data. Multiple different questionnaires were used, and it was difficult to ascertain if all the participants were experiencing active disease. Additionally, questionnaires are not always the best proxy for what is happening in everyday life. Lastly, the sample size of each individual study was small, and the studies only included adults.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by the 13 studies in this review, patients with ABDs have lower QOL scores and higher numbers of psychological symptoms. Clinicians should be mindful of this at-risk population and create opportunities in clinic to discuss personal hardship associated with the disease process and recommend psychiatric intervention if indicated. Additionally, family members often are overburdened with the chronicity of ABDs, and they should not be forgotten. Using one of the aforementioned questionnaires is a practical way to screen patients for lower QOL scores. We agree with Paradisi and colleagues19 that although these questionnaires may be helpful, clinicians still need to determine if the use of a dermatologic QOL evaluation tool in clinical practice improves patient satisfaction.

- Baum S, Sakka N, Artsi O, et al. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune blistering diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:482-489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.047

- Sebaratnam DF, McMillan JR, Werth VP, et al. Quality of life in patients with bullous dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:103-107. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.016

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Goldberg DP. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. Oxford University Press; 1972.

- Cano A, Sprafkin RP, Scaturo DJ, et al. Mental health screening in primary care: a comparison of 3 brief measures of psychological distress. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:206-210.

- Zigmond A, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370.

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20-40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

- Beck A, Alford B. Depression: Causes and Treatment. 2nd ed. Philadelphia University of Pennsylvania Press; 2009.

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, et al. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:185-192. doi:10.1002/da.20070

- Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, et al. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105-110.

- Nijsten TEC, Sampogna F, Chren M, et al. Testing and reducing Skindex-29 using Rasch analysis: Skindex-17. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1244-1250. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700212

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

- Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, et al. Quality of life, depression, anxiety and loneliness in patients with bullous pemphigoid: a case control study. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:601-603. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.2016493

- Penha MA, Farat JG, Miot HA, et al. Quality of life index in autoimmune bullous dermatosis patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:190-194. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153372

- Sung JY, Roh MR, Kim SC. Quality of life assessment in Korean patients with pemphigus. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:492-498.

- Moon SH, Kwon HI, Park HC, et al. Assessment of the quality of life in autoimmune blistering skin disease patients. Korean J Dermatol. 2014;52:402-409.

- Tabolli S, Pagliarello C, Paradisi A, et al. Burden of disease during quiescent periods in patients with pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1087-1091. doi:10.1111/bjd.12836

- Ghodsi SZ, Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and general health questionnaires. J Dermatol. 2012;39:141-144. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01382

- Paradisi A, Sampogna F, Di Pietro C, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:261-269. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.014

- Tabolli S, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. The health impact of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1029-1034. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08481.x

- Terrab Z, Benchikhi H, Maaroufi A, et al. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-328.

- Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris: results from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431-435. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05722.x

- Layegh P, Mokhber N, Javidi Z, et al. Depression in patients with pemphigus: is it a major concern? J Dermatol. 2014;40:434-437. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12067

- Kumar V, Mattoo SK, Handa S. Psychiatric morbidity in pemphigus and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:151-156. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2012.10.005

- Mazzotti E, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. Psychological distress and investment in one’s appearance in patients with pemphigus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:285-289. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03780.x

- Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five epidemiologic catchment area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1988;45:977-986. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002

- Cozzani E, Chinazzo C, Burlando M, et al. Ciprofloxacin as a trigger for bullous pemphigoid: the second case in the literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:E1202-E1204. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000283

- Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Silverdahl M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis measured with SF-36, DLQI and a subjective measure of disease activity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:430-434.

- Ren Z, Hsu DY, Brieva J, et al. Hospitalization, inpatient burden and comorbidities associated with bullous pemphigoid in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:87-99. doi:10.1111/bjd.14821

- Warner C, Kwak Y, Glover MH, et al. Bullous pemphigoid induced by hydrochlorothiazide therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:360-362.

- Mendonca FM, Martin-Gutierrez FJ, Rios-Martin JJ, et al. Three cases of bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors—one due to linagliptin. Dermatology. 2016;232:249-253. doi:10.1159/000443330

- Attaway A, Mersfelder TL, Vaishnav S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors: a case report and review of literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:24-28.

- Baum S, Sakka N, Artsi O, et al. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune blistering diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:482-489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.047

- Sebaratnam DF, McMillan JR, Werth VP, et al. Quality of life in patients with bullous dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:103-107. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.016

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Goldberg DP. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. Oxford University Press; 1972.

- Cano A, Sprafkin RP, Scaturo DJ, et al. Mental health screening in primary care: a comparison of 3 brief measures of psychological distress. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:206-210.

- Zigmond A, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370.

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20-40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

- Beck A, Alford B. Depression: Causes and Treatment. 2nd ed. Philadelphia University of Pennsylvania Press; 2009.

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, et al. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:185-192. doi:10.1002/da.20070

- Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, et al. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105-110.

- Nijsten TEC, Sampogna F, Chren M, et al. Testing and reducing Skindex-29 using Rasch analysis: Skindex-17. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1244-1250. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700212

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

- Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, et al. Quality of life, depression, anxiety and loneliness in patients with bullous pemphigoid: a case control study. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:601-603. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.2016493

- Penha MA, Farat JG, Miot HA, et al. Quality of life index in autoimmune bullous dermatosis patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:190-194. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153372

- Sung JY, Roh MR, Kim SC. Quality of life assessment in Korean patients with pemphigus. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:492-498.

- Moon SH, Kwon HI, Park HC, et al. Assessment of the quality of life in autoimmune blistering skin disease patients. Korean J Dermatol. 2014;52:402-409.

- Tabolli S, Pagliarello C, Paradisi A, et al. Burden of disease during quiescent periods in patients with pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1087-1091. doi:10.1111/bjd.12836

- Ghodsi SZ, Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and general health questionnaires. J Dermatol. 2012;39:141-144. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01382

- Paradisi A, Sampogna F, Di Pietro C, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:261-269. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.014

- Tabolli S, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. The health impact of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1029-1034. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08481.x

- Terrab Z, Benchikhi H, Maaroufi A, et al. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-328.

- Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris: results from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431-435. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05722.x

- Layegh P, Mokhber N, Javidi Z, et al. Depression in patients with pemphigus: is it a major concern? J Dermatol. 2014;40:434-437. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12067

- Kumar V, Mattoo SK, Handa S. Psychiatric morbidity in pemphigus and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:151-156. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2012.10.005

- Mazzotti E, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. Psychological distress and investment in one’s appearance in patients with pemphigus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:285-289. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03780.x

- Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five epidemiologic catchment area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1988;45:977-986. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002

- Cozzani E, Chinazzo C, Burlando M, et al. Ciprofloxacin as a trigger for bullous pemphigoid: the second case in the literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:E1202-E1204. doi:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000283

- Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Silverdahl M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis measured with SF-36, DLQI and a subjective measure of disease activity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:430-434.

- Ren Z, Hsu DY, Brieva J, et al. Hospitalization, inpatient burden and comorbidities associated with bullous pemphigoid in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:87-99. doi:10.1111/bjd.14821

- Warner C, Kwak Y, Glover MH, et al. Bullous pemphigoid induced by hydrochlorothiazide therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:360-362.

- Mendonca FM, Martin-Gutierrez FJ, Rios-Martin JJ, et al. Three cases of bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors—one due to linagliptin. Dermatology. 2016;232:249-253. doi:10.1159/000443330

- Attaway A, Mersfelder TL, Vaishnav S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors: a case report and review of literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:24-28.

Practice Points

- Autoimmune bullous dermatoses cause cutaneous lesions that are painful and disfiguring. These conditions affect a patient’s ability to perform everyday tasks, and individual lesions can take years to heal.

- Providers should take necessary steps to address patient well-being, especially at disease onset in patients with bullous dermatoses.