User login

Despite 30+ years of antismoking public policies and dramatic overall decline in secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure, .

No risk-free SHS exposure

Surendranath S. Shastri, MD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues underscored the U.S. Surgeon General’s determination that there is no risk-free level of SHS exposure in a recent JAMA Internal Medicine Research Letter.

“With the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019, which affects lung function, improving smoke-free policies to enhance air quality should be a growing priority,”they wrote.

Dr. Shastri and colleagues looked at 2011-2018 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which detailed prevalence of SHS exposure in the U.S. population aged 3 years and older using interviews and biological specimens to test for cotinine levels. For the survey, nonsmokers having serum cotinine levels of 0.05 to 10 ng/mL were considered to have SHS exposure.

While the prevalence of SHS exposure among nonsmokers declined from 87.5% to 25.3% between 1988 and 2012, levels have stagnated since 2012 and racial and economic disparities are evident. Higher smoking rates, less knowledge about health risks, higher workplace exposure, greater likelihood of living in low-income, multi-unit housing, plus having their communities targeted by tobacco companies, may all help explain higher serum levels of cotinine in populations with lower socioeconomic status.

“Multivariable logistic regression identified younger age (odds ratio [OR], 1.88, for 12-19 years, and OR, 2.29, for 3-11 years), non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity (OR, 2.75), less than high school education (OR, 1.59), and living below the poverty level (OR, 2.61) as risk factors for SHSe in the 2017-2018 cycle, with little change across all data cycles,” the researchers wrote.

Disparities in SHS exposure

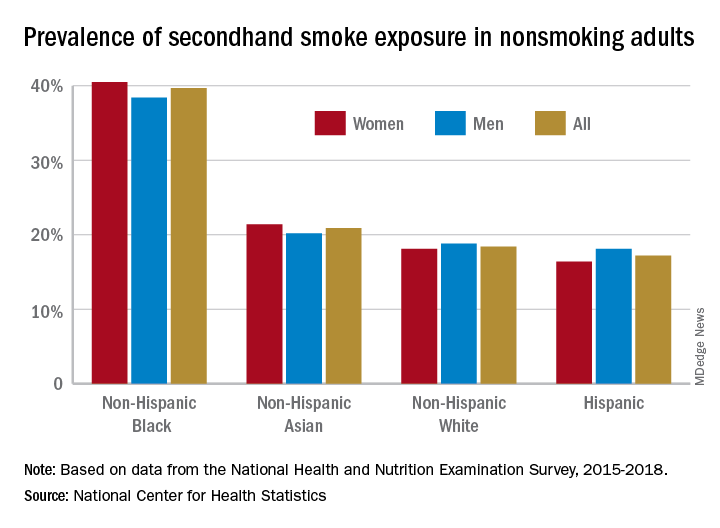

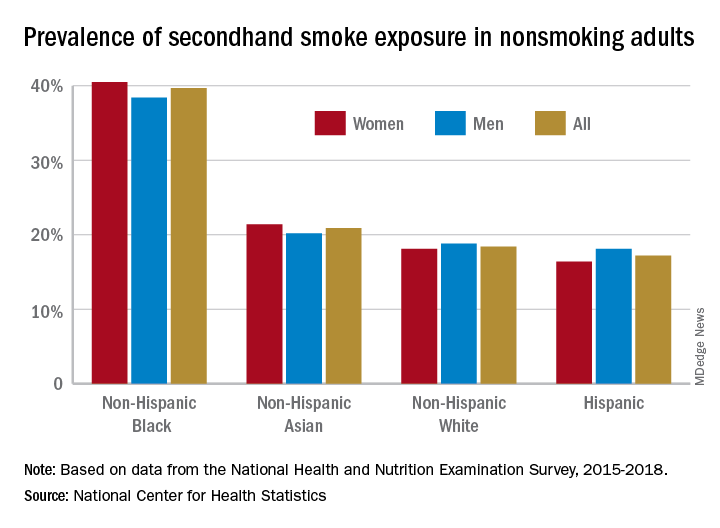

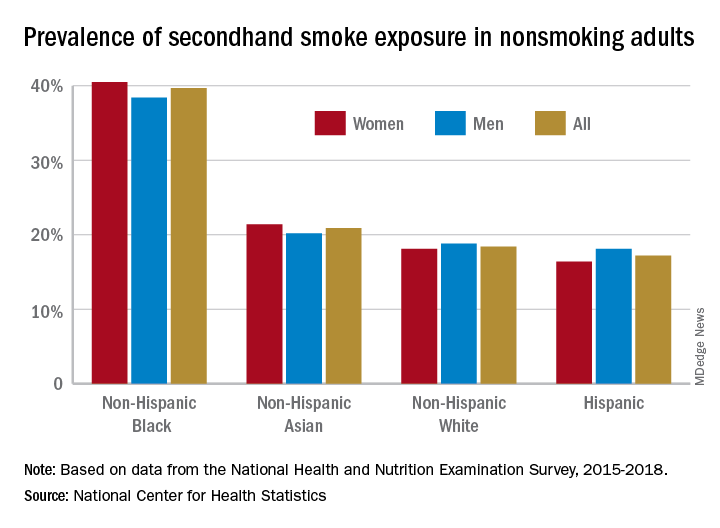

A second report from NHANES data for 2015-2018, published in a National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief (No. 396, February 2021) showed that 20.8% of nonsmoking U.S. adults had SHS exposure, again with greater prevalence among non-Hispanic Black adults (39.7%), than for non-Hispanic White (18.4%), non-Hispanic Asian (20.9%), and Hispanic (17.2%) adults. Exposure was also greater in the younger age groups, with SHS rates for adults aged 18-39 years, 40-59 years, and ≥60 years at 25.6%, 19.1%, and 17.6%, respectively. Lower education (high school or less vs. some college education) and lower income levels were also associated with higher levels of SHS exposure. The investigators noted that among households with smokers, non-Hispanic Black adults are less likely to have complete smoking bans in homes, and among Medicaid or uninsured parents of any race or ethnicity, bans on smoking in family vehicles are less likely.

Overall, the prevalence of SHS exposure declined from 27.7% to 20.7% from 2009 to 2018, but the decreases were mediated by race and income.

SHS exposure in private spaces

A research brief from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on SHS exposure in homes and vehicles in the U.S. among middle and high school students also found a general decline in SHS exposure over 2011-2018 in homes (26.8%-20.9%; P < .001) and vehicles (30.2%-19.8%; P < .001). The findings, derived from the National Youth Tobacco Survey for 2011-2019, showed that no reduction occurred in homes among non-Hispanic Black students. Overall, a significant difference in home SHS exposure was observed by race/ethnicity: non-Hispanic Black (28.4%) and non-Hispanic White (27.4%) students both had a higher prevalence compared with Hispanic (20.0%) and non-Hispanic other (20.2%) students (P < .001).

Progress in reducing SHS exposure in public spaces has been made over the last 2 decades, with 27 states and more than 1,000 municipalities implementing comprehensive smoke-free laws that prohibit smoking in indoor public places, including workplaces, restaurants, and bars. While the prevalence of voluntary smoke-free home (83.7%) and vehicle (78.1%) rules has increased over time, private settings remain major sources of SHS exposure for many people, including youths. “Although SHS exposures have declined,” the authors wrote, “more than 6 million young people remain exposed to SHS in these private settings.”

In reviewing the data, Mary Cataletto, MD, FCCP, clinical professor of pediatrics at NYU Long Island School of Medicine, stated that these studies “highlight the need for implementation of smoke-free policies to reduce exposure to secondhand smoke, especially in homes and cars and with focused advocacy efforts in highly affected communities.”

Panagis Galiatsatos, MD, MHS, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, emphasized implementation of smoke-free policies but also treatment for smokers. “I’m not at all surprised by these statistics,” he noted in an interview. “Public health policies have helped us to get to where we are now, but there’s a reason that we have plateaued over the last decade. It’s hard to mitigate secondhand smoke exposure because the ones who are smoking now are the most refractory, challenging cases. ... You need good clinical interventions with counseling supported by pharmacological agents to help them if you want to stop secondhand smoke exposure.” He added, “You have to look at current smokers no differently than you look at patients with stage IV cancer – a group that requires a lot of resources to help them get through. Remember, all of them want to quit, but the promise of well-designed, precision-medicine strategies to help them quit has not been kept. Public health policy isn’t going to do it. We need to manage these patients clinically.”

The investigators had no conflict disclosures.

Despite 30+ years of antismoking public policies and dramatic overall decline in secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure, .

No risk-free SHS exposure

Surendranath S. Shastri, MD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues underscored the U.S. Surgeon General’s determination that there is no risk-free level of SHS exposure in a recent JAMA Internal Medicine Research Letter.

“With the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019, which affects lung function, improving smoke-free policies to enhance air quality should be a growing priority,”they wrote.

Dr. Shastri and colleagues looked at 2011-2018 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which detailed prevalence of SHS exposure in the U.S. population aged 3 years and older using interviews and biological specimens to test for cotinine levels. For the survey, nonsmokers having serum cotinine levels of 0.05 to 10 ng/mL were considered to have SHS exposure.

While the prevalence of SHS exposure among nonsmokers declined from 87.5% to 25.3% between 1988 and 2012, levels have stagnated since 2012 and racial and economic disparities are evident. Higher smoking rates, less knowledge about health risks, higher workplace exposure, greater likelihood of living in low-income, multi-unit housing, plus having their communities targeted by tobacco companies, may all help explain higher serum levels of cotinine in populations with lower socioeconomic status.

“Multivariable logistic regression identified younger age (odds ratio [OR], 1.88, for 12-19 years, and OR, 2.29, for 3-11 years), non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity (OR, 2.75), less than high school education (OR, 1.59), and living below the poverty level (OR, 2.61) as risk factors for SHSe in the 2017-2018 cycle, with little change across all data cycles,” the researchers wrote.

Disparities in SHS exposure

A second report from NHANES data for 2015-2018, published in a National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief (No. 396, February 2021) showed that 20.8% of nonsmoking U.S. adults had SHS exposure, again with greater prevalence among non-Hispanic Black adults (39.7%), than for non-Hispanic White (18.4%), non-Hispanic Asian (20.9%), and Hispanic (17.2%) adults. Exposure was also greater in the younger age groups, with SHS rates for adults aged 18-39 years, 40-59 years, and ≥60 years at 25.6%, 19.1%, and 17.6%, respectively. Lower education (high school or less vs. some college education) and lower income levels were also associated with higher levels of SHS exposure. The investigators noted that among households with smokers, non-Hispanic Black adults are less likely to have complete smoking bans in homes, and among Medicaid or uninsured parents of any race or ethnicity, bans on smoking in family vehicles are less likely.

Overall, the prevalence of SHS exposure declined from 27.7% to 20.7% from 2009 to 2018, but the decreases were mediated by race and income.

SHS exposure in private spaces

A research brief from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on SHS exposure in homes and vehicles in the U.S. among middle and high school students also found a general decline in SHS exposure over 2011-2018 in homes (26.8%-20.9%; P < .001) and vehicles (30.2%-19.8%; P < .001). The findings, derived from the National Youth Tobacco Survey for 2011-2019, showed that no reduction occurred in homes among non-Hispanic Black students. Overall, a significant difference in home SHS exposure was observed by race/ethnicity: non-Hispanic Black (28.4%) and non-Hispanic White (27.4%) students both had a higher prevalence compared with Hispanic (20.0%) and non-Hispanic other (20.2%) students (P < .001).

Progress in reducing SHS exposure in public spaces has been made over the last 2 decades, with 27 states and more than 1,000 municipalities implementing comprehensive smoke-free laws that prohibit smoking in indoor public places, including workplaces, restaurants, and bars. While the prevalence of voluntary smoke-free home (83.7%) and vehicle (78.1%) rules has increased over time, private settings remain major sources of SHS exposure for many people, including youths. “Although SHS exposures have declined,” the authors wrote, “more than 6 million young people remain exposed to SHS in these private settings.”

In reviewing the data, Mary Cataletto, MD, FCCP, clinical professor of pediatrics at NYU Long Island School of Medicine, stated that these studies “highlight the need for implementation of smoke-free policies to reduce exposure to secondhand smoke, especially in homes and cars and with focused advocacy efforts in highly affected communities.”

Panagis Galiatsatos, MD, MHS, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, emphasized implementation of smoke-free policies but also treatment for smokers. “I’m not at all surprised by these statistics,” he noted in an interview. “Public health policies have helped us to get to where we are now, but there’s a reason that we have plateaued over the last decade. It’s hard to mitigate secondhand smoke exposure because the ones who are smoking now are the most refractory, challenging cases. ... You need good clinical interventions with counseling supported by pharmacological agents to help them if you want to stop secondhand smoke exposure.” He added, “You have to look at current smokers no differently than you look at patients with stage IV cancer – a group that requires a lot of resources to help them get through. Remember, all of them want to quit, but the promise of well-designed, precision-medicine strategies to help them quit has not been kept. Public health policy isn’t going to do it. We need to manage these patients clinically.”

The investigators had no conflict disclosures.

Despite 30+ years of antismoking public policies and dramatic overall decline in secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure, .

No risk-free SHS exposure

Surendranath S. Shastri, MD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues underscored the U.S. Surgeon General’s determination that there is no risk-free level of SHS exposure in a recent JAMA Internal Medicine Research Letter.

“With the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019, which affects lung function, improving smoke-free policies to enhance air quality should be a growing priority,”they wrote.

Dr. Shastri and colleagues looked at 2011-2018 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which detailed prevalence of SHS exposure in the U.S. population aged 3 years and older using interviews and biological specimens to test for cotinine levels. For the survey, nonsmokers having serum cotinine levels of 0.05 to 10 ng/mL were considered to have SHS exposure.

While the prevalence of SHS exposure among nonsmokers declined from 87.5% to 25.3% between 1988 and 2012, levels have stagnated since 2012 and racial and economic disparities are evident. Higher smoking rates, less knowledge about health risks, higher workplace exposure, greater likelihood of living in low-income, multi-unit housing, plus having their communities targeted by tobacco companies, may all help explain higher serum levels of cotinine in populations with lower socioeconomic status.

“Multivariable logistic regression identified younger age (odds ratio [OR], 1.88, for 12-19 years, and OR, 2.29, for 3-11 years), non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity (OR, 2.75), less than high school education (OR, 1.59), and living below the poverty level (OR, 2.61) as risk factors for SHSe in the 2017-2018 cycle, with little change across all data cycles,” the researchers wrote.

Disparities in SHS exposure

A second report from NHANES data for 2015-2018, published in a National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief (No. 396, February 2021) showed that 20.8% of nonsmoking U.S. adults had SHS exposure, again with greater prevalence among non-Hispanic Black adults (39.7%), than for non-Hispanic White (18.4%), non-Hispanic Asian (20.9%), and Hispanic (17.2%) adults. Exposure was also greater in the younger age groups, with SHS rates for adults aged 18-39 years, 40-59 years, and ≥60 years at 25.6%, 19.1%, and 17.6%, respectively. Lower education (high school or less vs. some college education) and lower income levels were also associated with higher levels of SHS exposure. The investigators noted that among households with smokers, non-Hispanic Black adults are less likely to have complete smoking bans in homes, and among Medicaid or uninsured parents of any race or ethnicity, bans on smoking in family vehicles are less likely.

Overall, the prevalence of SHS exposure declined from 27.7% to 20.7% from 2009 to 2018, but the decreases were mediated by race and income.

SHS exposure in private spaces

A research brief from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on SHS exposure in homes and vehicles in the U.S. among middle and high school students also found a general decline in SHS exposure over 2011-2018 in homes (26.8%-20.9%; P < .001) and vehicles (30.2%-19.8%; P < .001). The findings, derived from the National Youth Tobacco Survey for 2011-2019, showed that no reduction occurred in homes among non-Hispanic Black students. Overall, a significant difference in home SHS exposure was observed by race/ethnicity: non-Hispanic Black (28.4%) and non-Hispanic White (27.4%) students both had a higher prevalence compared with Hispanic (20.0%) and non-Hispanic other (20.2%) students (P < .001).

Progress in reducing SHS exposure in public spaces has been made over the last 2 decades, with 27 states and more than 1,000 municipalities implementing comprehensive smoke-free laws that prohibit smoking in indoor public places, including workplaces, restaurants, and bars. While the prevalence of voluntary smoke-free home (83.7%) and vehicle (78.1%) rules has increased over time, private settings remain major sources of SHS exposure for many people, including youths. “Although SHS exposures have declined,” the authors wrote, “more than 6 million young people remain exposed to SHS in these private settings.”

In reviewing the data, Mary Cataletto, MD, FCCP, clinical professor of pediatrics at NYU Long Island School of Medicine, stated that these studies “highlight the need for implementation of smoke-free policies to reduce exposure to secondhand smoke, especially in homes and cars and with focused advocacy efforts in highly affected communities.”

Panagis Galiatsatos, MD, MHS, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, emphasized implementation of smoke-free policies but also treatment for smokers. “I’m not at all surprised by these statistics,” he noted in an interview. “Public health policies have helped us to get to where we are now, but there’s a reason that we have plateaued over the last decade. It’s hard to mitigate secondhand smoke exposure because the ones who are smoking now are the most refractory, challenging cases. ... You need good clinical interventions with counseling supported by pharmacological agents to help them if you want to stop secondhand smoke exposure.” He added, “You have to look at current smokers no differently than you look at patients with stage IV cancer – a group that requires a lot of resources to help them get through. Remember, all of them want to quit, but the promise of well-designed, precision-medicine strategies to help them quit has not been kept. Public health policy isn’t going to do it. We need to manage these patients clinically.”

The investigators had no conflict disclosures.