User login

It’s no secret that documenting and coding one’s work is not the average hospitalist’s favorite thing to do. It’s probably not even in the top 10 or 20. In fact, many consider the whole documentation process a “thorn in the side.”

“When I first started working, I couldn’t believe that I could get audited and fined just because I didn’t add ‘10-point’ or ‘12-point’ to my note of ‘review of systems: negative,’ ” says hospitalist Amaka Nweke, MD, assistant director with Hospitalists Management Group (HMG) at Kenosha Medical Center in Kenosha, Wis. “I had a lot of frustration, because I had to repackage and re-present my notes in a manner that makes sense to Medicare but makes no sense to physicians.”

Like it or not, healthcare providers live in a highly regulated world, says Richard D. Pinson, MD, FACP, CCS, who became a certified coding specialist and formed his own consulting company, Houston-based HCQ Consulting, to help hospitals and physicians achieve diagnostic accuracy for inpatient care. Documentation and coding have become a serious, high-stakes word game, he says. “Perfectly good clinical documentation, especially with some important diagnoses, may not correspond at all to what is required by the strict coding rules that govern code assignments,” he says.

A hospitalist’s documentation is at the heart of accurate coding, whether it’s for the hospital’s DRG reimbursement, quality and performance scores, or for assigning current procedural terminology (CPT) and evaluation and management (E/M) codes for billing for their own professional services. And if hospitalists don’t buy into the coding mindset, they risk decreased reimbursement for their services, monetary losses for the hospital, Medicare audits, compromised quality scores for both the hospital and themselves, and noncompliance.

“If your documentation is not up to par, then the hospital may get fined and lose money, and you can’t prove your worth as a hospitalist,” Dr. Nweke says.

What’s at Stake?

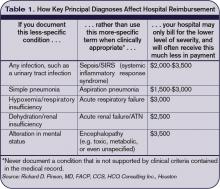

Inadequate documentation results in “undercoding” a patient’s condition and underpayment to your hospital (see Table 1, right). Undercoding also can result in inadequate representation of the severity of a patient’s illness, complexity, and cost of care. If a patient gets worse in the hospital, then that initial lower severity of illness might show up in poor performance scores on outcome measures. If a patient’s severity of illness is miscoded, Medicare might question the medical necessity for inpatient admission and deny payment.

On the other hand, if overcoding occurs because the clinical criteria for a specific diagnosis have not been met, Medicare will take action to recover the overpayment, leveling penalties and sanctions. (For more information on Medicare’s Recovery Audit Contractor program, dubbed “Medicare’s repo men” by Dr. Pinson, see “Take Proactive Approach to Recovery Audit Contractors,” p. 28.)

Lack of specificity also hampers reimbursement for professional fees, says Barb Pierce, CCS-P, ACS-EM, president of Barb Pierce Coding and Consulting Inc. of West Des Moines, Iowa. “Unfortunately,” she observes, “the code isn’t just based on decision-making, which is why physicians went to school for all those years. The guidelines [Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services] mandate that if you forget one little bullet in history or examination, even if you’ve got the riskiest, highest-level, decision-making patient in front of you, that could pull down the whole code selection.”1

How costly might such small mistakes be for an HM group? According to the State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data survey, internal-medicine hospitalists generate a median of 1.86 work relative value units (wRVUs) per encounter, and collect $45.57 per wRVU.2 If a hospitalist has 2,200 encounters per year and averages only 1.65 wRVUs per encounter, improving documentation and coding performance could add an additional 0.21 wRVUs, meeting the national average. Multiplying those 2,200 encounters by the national average of 1.86, the hospitalist could potentially add an additional 462 wRVUs for the year. Such documentation improvement—up to the national average—would equate to $21,053 in additional billed revenue without increasing the physician’s overall workload.

Dr. Pinson explains that physicians often perceive their time constraints as so severe that they’d be hard pressed to find the time to learn about documentation and coding. But he maintains that even short seminars yield “a huge amount of information that would astound [hospitalists], in terms of usefulness for their own clinical practices.”

Barriers to the Coding Mindset

Most hospitalists receive little or no training in documentation and coding during medical school or residency. The lack of education is further complicated because there are several coding sets healthcare providers must master, each with different rules governing assignment of diagnoses and levels of care (see “Coding Sets: Separate but Overlapping,” above).

Inexperience with coding guidelines can lead to mismatches. Nelly Leon-Chisen, RHIA, director of coding and classification for the American Hospital Association (AHA), gives one example: The ICD-9-CM Official Coding Guideline stipulates that coders cannot assign diagnosis codes based on lab results.3 So although it might appear intuitive to a physician that repeated blood sugars and monitoring of insulin levels indicate a patient has diabetes, the coder cannot assign the diagnosis unless it’s explicitly stated in the record.

Some physicians could simply be using outmoded terminology, such as “renal insufficiency” instead of “acute renal failure,” Dr. Pinson notes. If hospitalists learn to focus on evidence-based clinical criteria to support the codes, it leads to more effective care, he says.

The nature of hospitalist programs might not lend itself to efficient revenue-cycle processes for their own professional billing, says Jeri Leong, RN, CPC, CPC-H, president and CEO of Honolulu-based Healthcare Coding Consultants of Hawaii. If the HM group contracts with several hospitals, the hospitalists will be together rarely as a group, “so they don’t have the luxury of sitting down together with their billers to get important feedback and coding updates,” she says.

Leong’s company identifies missed charges, for instance, when charge tags from different shifts do not get married together (Hospitalist A might round on the patient in the morning and turn in a charge tag; Hospitalist B might do a procedure in the afternoon, but the two tags do not get combined). Examples such as these, she says, “can be an issue from a compliance perspective, and can leave money on the table.”

One of the problems Kathy DeVault, RHIA, CCS, CCS-P, manager of professional practice resources for the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA), sees is a lack of continuity between initial admitting diagnosis and discharge summaries. For example, a hospitalist might admit a patient for acute renal failure—the correct diagnosis—and be able to reverse the condition fairly quickly, especially if the failure is due to dehydration.

The patient, whose issue is resolved, could be discharged by an attending physician who does not note the acute diagnosis in the summary. “That acute condition disappears, and the RAC auditor may then challenge the claim for payment,” DeVault says.

The Remedies

While physicians might think that they don’t have the time to acquire coding education, there could be other incentives coming down the pike. Dr. Pinson has noticed that hospitals are beginning to incorporate documentation accuracy into their contractual reimbursement formulas.

Documentation fixes vary according to domain. A hospital’s clinical documentation specialists can query physicians for clarity and detail in their notes; for instance, a diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF) must be accompanied by additional documentation stating whether the CHF is acute or chronic, and whether it is systolic or diastolic.

Many hospitals have instituted clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs, sometimes called clinical documentation integrity programs, to address documentation discrepancies. CDI programs are essential to hospitals’ financial survival, Dr. Pinson says, and hospitalists are ideally positioned to join those efforts.

“[The hospitalists] are the most important people to the hospital in all of this,” he says. “They’re at the center of this whirlpool. If you have these skills, your value to the hospital and to your group is greatly enhanced.” (Visit the-hospitalist.org to listen to Dr. Pinson discuss HM’s role in documentation improvement.)

Leon-Chisen also says that the relationship between coders and physicians should be collaborative. “If it’s adversarial, nobody wins,” she points out, adding that CDI programs present an opportunity for mutual education.

Conducting audits of the practice’s documentation and coding can identify coding strengths and weaknesses, says Pierce, who is faculty for SHM’s billing and coding pre-course and regularly consults with hospitalist groups. Audits are helpful, she says, not just for increasing group revenue, but for compliance reasons as well. “You need to know what you’re doing well, and what you’re not doing quite so well, and get it fixed internally before an entity like Medicare discovers it,” she says.

It’s no doubt difficult for a busy HM group to stay on top of annual coding updates and changes to guidelines for reporting their services, Leong notes. Her company has worked with many hospitalist groups over the years, offering coding workshops, “back end” audits, and real-time feedback of E/M and CPT coding choices. If all of the hospitalists in a group cannot convene simultaneously, Leong provides the feedback (in the form of a scorecard) to the group’s physician champion, who becomes the lead contact to help those physicians who struggle more with their coding. (Leong talks more about real-time feedback and capturing CPT and E/M codes at the-hospitalist.org.)

In lieu of hiring professional coders, some HM groups use electronic coding devices. The software could be a standalone product, or it could interface with other products, such as electronic medical records (EMRs). These programs assist with a variety of coding-related activities, such as CPT or ICD-9 lookups, or calculation of E/M key components with assignment of an appropriate level of billing. Leong, however, cautions too much reliance on technology.

“While these devices can be accurate, compact, and convenient, it’s important to maintain a current [software] subscription to keep abreast of updates to the code sets, which occur sometimes as often as quarterly,” she says.

Pierce adds that coding tools should be double-checked against an audit tool. She has sometimes found discrepancies when auditing against an EMR product that assigns the E/M level.

Attitude Adjustment

Coding experts emphasize that physicians need not worry about mastering coding manuals, but they should forge relationships with both their hospital’s billers and the coders for their practice.

Dr. Nweke took advantage of coding and billing workshops offered by her group, HMG, and through the seminars began to understand what a DRG meant not just for her hospital but for her own evaluations and the expansion of her HM group, too. “Now, when I get questions from billers and coders, I try to answer them quickly,” she says. “I don’t look upon them as the enemy, but rather as people who are helping me document appropriately, so I don’t get audited by Medicare. I think the way you view the coders and billers definitely affects your willingness to learn.”

Dr. Nweke also takes a broader view of her role as a hospitalist. “You are there to take care of patients and assist with transitioning them in and out of the hospital, but you’re also there to ensure that the hospital remains afloat financially,” she says. “Your documentation plays a huge role in that. We have a huge contribution to make.”

The patient gains, too, says Leon-Chisen, who explains that documentation should be as accurate as possible “because someone else—the patient’s primary physician—will be taking over care of that patient and needs to understand what happened in the hospital.”

“The bottom line,” Dr. Pinson says, “is that we need accurate documentation that can be correctly coded to reflect the true complexity of care and severity of illness. If we do that, good things will follow.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2011.

- State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. Society of Hospital Medicine and Medical Group Management Association; Philadelphia and Englewood, Colo.; 2010.

- ICD-9-CM Official Coding Guidelines. CMS and National Center for Health Statistics; Washington, D.C.; 2008. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/cpt/icd9cm_coding_guidelines_08_09_full.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2011.

It’s no secret that documenting and coding one’s work is not the average hospitalist’s favorite thing to do. It’s probably not even in the top 10 or 20. In fact, many consider the whole documentation process a “thorn in the side.”

“When I first started working, I couldn’t believe that I could get audited and fined just because I didn’t add ‘10-point’ or ‘12-point’ to my note of ‘review of systems: negative,’ ” says hospitalist Amaka Nweke, MD, assistant director with Hospitalists Management Group (HMG) at Kenosha Medical Center in Kenosha, Wis. “I had a lot of frustration, because I had to repackage and re-present my notes in a manner that makes sense to Medicare but makes no sense to physicians.”

Like it or not, healthcare providers live in a highly regulated world, says Richard D. Pinson, MD, FACP, CCS, who became a certified coding specialist and formed his own consulting company, Houston-based HCQ Consulting, to help hospitals and physicians achieve diagnostic accuracy for inpatient care. Documentation and coding have become a serious, high-stakes word game, he says. “Perfectly good clinical documentation, especially with some important diagnoses, may not correspond at all to what is required by the strict coding rules that govern code assignments,” he says.

A hospitalist’s documentation is at the heart of accurate coding, whether it’s for the hospital’s DRG reimbursement, quality and performance scores, or for assigning current procedural terminology (CPT) and evaluation and management (E/M) codes for billing for their own professional services. And if hospitalists don’t buy into the coding mindset, they risk decreased reimbursement for their services, monetary losses for the hospital, Medicare audits, compromised quality scores for both the hospital and themselves, and noncompliance.

“If your documentation is not up to par, then the hospital may get fined and lose money, and you can’t prove your worth as a hospitalist,” Dr. Nweke says.

What’s at Stake?

Inadequate documentation results in “undercoding” a patient’s condition and underpayment to your hospital (see Table 1, right). Undercoding also can result in inadequate representation of the severity of a patient’s illness, complexity, and cost of care. If a patient gets worse in the hospital, then that initial lower severity of illness might show up in poor performance scores on outcome measures. If a patient’s severity of illness is miscoded, Medicare might question the medical necessity for inpatient admission and deny payment.

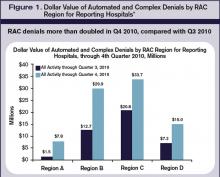

On the other hand, if overcoding occurs because the clinical criteria for a specific diagnosis have not been met, Medicare will take action to recover the overpayment, leveling penalties and sanctions. (For more information on Medicare’s Recovery Audit Contractor program, dubbed “Medicare’s repo men” by Dr. Pinson, see “Take Proactive Approach to Recovery Audit Contractors,” p. 28.)

Lack of specificity also hampers reimbursement for professional fees, says Barb Pierce, CCS-P, ACS-EM, president of Barb Pierce Coding and Consulting Inc. of West Des Moines, Iowa. “Unfortunately,” she observes, “the code isn’t just based on decision-making, which is why physicians went to school for all those years. The guidelines [Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services] mandate that if you forget one little bullet in history or examination, even if you’ve got the riskiest, highest-level, decision-making patient in front of you, that could pull down the whole code selection.”1

How costly might such small mistakes be for an HM group? According to the State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data survey, internal-medicine hospitalists generate a median of 1.86 work relative value units (wRVUs) per encounter, and collect $45.57 per wRVU.2 If a hospitalist has 2,200 encounters per year and averages only 1.65 wRVUs per encounter, improving documentation and coding performance could add an additional 0.21 wRVUs, meeting the national average. Multiplying those 2,200 encounters by the national average of 1.86, the hospitalist could potentially add an additional 462 wRVUs for the year. Such documentation improvement—up to the national average—would equate to $21,053 in additional billed revenue without increasing the physician’s overall workload.

Dr. Pinson explains that physicians often perceive their time constraints as so severe that they’d be hard pressed to find the time to learn about documentation and coding. But he maintains that even short seminars yield “a huge amount of information that would astound [hospitalists], in terms of usefulness for their own clinical practices.”

Barriers to the Coding Mindset

Most hospitalists receive little or no training in documentation and coding during medical school or residency. The lack of education is further complicated because there are several coding sets healthcare providers must master, each with different rules governing assignment of diagnoses and levels of care (see “Coding Sets: Separate but Overlapping,” above).

Inexperience with coding guidelines can lead to mismatches. Nelly Leon-Chisen, RHIA, director of coding and classification for the American Hospital Association (AHA), gives one example: The ICD-9-CM Official Coding Guideline stipulates that coders cannot assign diagnosis codes based on lab results.3 So although it might appear intuitive to a physician that repeated blood sugars and monitoring of insulin levels indicate a patient has diabetes, the coder cannot assign the diagnosis unless it’s explicitly stated in the record.

Some physicians could simply be using outmoded terminology, such as “renal insufficiency” instead of “acute renal failure,” Dr. Pinson notes. If hospitalists learn to focus on evidence-based clinical criteria to support the codes, it leads to more effective care, he says.

The nature of hospitalist programs might not lend itself to efficient revenue-cycle processes for their own professional billing, says Jeri Leong, RN, CPC, CPC-H, president and CEO of Honolulu-based Healthcare Coding Consultants of Hawaii. If the HM group contracts with several hospitals, the hospitalists will be together rarely as a group, “so they don’t have the luxury of sitting down together with their billers to get important feedback and coding updates,” she says.

Leong’s company identifies missed charges, for instance, when charge tags from different shifts do not get married together (Hospitalist A might round on the patient in the morning and turn in a charge tag; Hospitalist B might do a procedure in the afternoon, but the two tags do not get combined). Examples such as these, she says, “can be an issue from a compliance perspective, and can leave money on the table.”

One of the problems Kathy DeVault, RHIA, CCS, CCS-P, manager of professional practice resources for the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA), sees is a lack of continuity between initial admitting diagnosis and discharge summaries. For example, a hospitalist might admit a patient for acute renal failure—the correct diagnosis—and be able to reverse the condition fairly quickly, especially if the failure is due to dehydration.

The patient, whose issue is resolved, could be discharged by an attending physician who does not note the acute diagnosis in the summary. “That acute condition disappears, and the RAC auditor may then challenge the claim for payment,” DeVault says.

The Remedies

While physicians might think that they don’t have the time to acquire coding education, there could be other incentives coming down the pike. Dr. Pinson has noticed that hospitals are beginning to incorporate documentation accuracy into their contractual reimbursement formulas.

Documentation fixes vary according to domain. A hospital’s clinical documentation specialists can query physicians for clarity and detail in their notes; for instance, a diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF) must be accompanied by additional documentation stating whether the CHF is acute or chronic, and whether it is systolic or diastolic.

Many hospitals have instituted clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs, sometimes called clinical documentation integrity programs, to address documentation discrepancies. CDI programs are essential to hospitals’ financial survival, Dr. Pinson says, and hospitalists are ideally positioned to join those efforts.

“[The hospitalists] are the most important people to the hospital in all of this,” he says. “They’re at the center of this whirlpool. If you have these skills, your value to the hospital and to your group is greatly enhanced.” (Visit the-hospitalist.org to listen to Dr. Pinson discuss HM’s role in documentation improvement.)

Leon-Chisen also says that the relationship between coders and physicians should be collaborative. “If it’s adversarial, nobody wins,” she points out, adding that CDI programs present an opportunity for mutual education.

Conducting audits of the practice’s documentation and coding can identify coding strengths and weaknesses, says Pierce, who is faculty for SHM’s billing and coding pre-course and regularly consults with hospitalist groups. Audits are helpful, she says, not just for increasing group revenue, but for compliance reasons as well. “You need to know what you’re doing well, and what you’re not doing quite so well, and get it fixed internally before an entity like Medicare discovers it,” she says.

It’s no doubt difficult for a busy HM group to stay on top of annual coding updates and changes to guidelines for reporting their services, Leong notes. Her company has worked with many hospitalist groups over the years, offering coding workshops, “back end” audits, and real-time feedback of E/M and CPT coding choices. If all of the hospitalists in a group cannot convene simultaneously, Leong provides the feedback (in the form of a scorecard) to the group’s physician champion, who becomes the lead contact to help those physicians who struggle more with their coding. (Leong talks more about real-time feedback and capturing CPT and E/M codes at the-hospitalist.org.)

In lieu of hiring professional coders, some HM groups use electronic coding devices. The software could be a standalone product, or it could interface with other products, such as electronic medical records (EMRs). These programs assist with a variety of coding-related activities, such as CPT or ICD-9 lookups, or calculation of E/M key components with assignment of an appropriate level of billing. Leong, however, cautions too much reliance on technology.

“While these devices can be accurate, compact, and convenient, it’s important to maintain a current [software] subscription to keep abreast of updates to the code sets, which occur sometimes as often as quarterly,” she says.

Pierce adds that coding tools should be double-checked against an audit tool. She has sometimes found discrepancies when auditing against an EMR product that assigns the E/M level.

Attitude Adjustment

Coding experts emphasize that physicians need not worry about mastering coding manuals, but they should forge relationships with both their hospital’s billers and the coders for their practice.

Dr. Nweke took advantage of coding and billing workshops offered by her group, HMG, and through the seminars began to understand what a DRG meant not just for her hospital but for her own evaluations and the expansion of her HM group, too. “Now, when I get questions from billers and coders, I try to answer them quickly,” she says. “I don’t look upon them as the enemy, but rather as people who are helping me document appropriately, so I don’t get audited by Medicare. I think the way you view the coders and billers definitely affects your willingness to learn.”

Dr. Nweke also takes a broader view of her role as a hospitalist. “You are there to take care of patients and assist with transitioning them in and out of the hospital, but you’re also there to ensure that the hospital remains afloat financially,” she says. “Your documentation plays a huge role in that. We have a huge contribution to make.”

The patient gains, too, says Leon-Chisen, who explains that documentation should be as accurate as possible “because someone else—the patient’s primary physician—will be taking over care of that patient and needs to understand what happened in the hospital.”

“The bottom line,” Dr. Pinson says, “is that we need accurate documentation that can be correctly coded to reflect the true complexity of care and severity of illness. If we do that, good things will follow.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2011.

- State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. Society of Hospital Medicine and Medical Group Management Association; Philadelphia and Englewood, Colo.; 2010.

- ICD-9-CM Official Coding Guidelines. CMS and National Center for Health Statistics; Washington, D.C.; 2008. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/cpt/icd9cm_coding_guidelines_08_09_full.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2011.

It’s no secret that documenting and coding one’s work is not the average hospitalist’s favorite thing to do. It’s probably not even in the top 10 or 20. In fact, many consider the whole documentation process a “thorn in the side.”

“When I first started working, I couldn’t believe that I could get audited and fined just because I didn’t add ‘10-point’ or ‘12-point’ to my note of ‘review of systems: negative,’ ” says hospitalist Amaka Nweke, MD, assistant director with Hospitalists Management Group (HMG) at Kenosha Medical Center in Kenosha, Wis. “I had a lot of frustration, because I had to repackage and re-present my notes in a manner that makes sense to Medicare but makes no sense to physicians.”

Like it or not, healthcare providers live in a highly regulated world, says Richard D. Pinson, MD, FACP, CCS, who became a certified coding specialist and formed his own consulting company, Houston-based HCQ Consulting, to help hospitals and physicians achieve diagnostic accuracy for inpatient care. Documentation and coding have become a serious, high-stakes word game, he says. “Perfectly good clinical documentation, especially with some important diagnoses, may not correspond at all to what is required by the strict coding rules that govern code assignments,” he says.

A hospitalist’s documentation is at the heart of accurate coding, whether it’s for the hospital’s DRG reimbursement, quality and performance scores, or for assigning current procedural terminology (CPT) and evaluation and management (E/M) codes for billing for their own professional services. And if hospitalists don’t buy into the coding mindset, they risk decreased reimbursement for their services, monetary losses for the hospital, Medicare audits, compromised quality scores for both the hospital and themselves, and noncompliance.

“If your documentation is not up to par, then the hospital may get fined and lose money, and you can’t prove your worth as a hospitalist,” Dr. Nweke says.

What’s at Stake?

Inadequate documentation results in “undercoding” a patient’s condition and underpayment to your hospital (see Table 1, right). Undercoding also can result in inadequate representation of the severity of a patient’s illness, complexity, and cost of care. If a patient gets worse in the hospital, then that initial lower severity of illness might show up in poor performance scores on outcome measures. If a patient’s severity of illness is miscoded, Medicare might question the medical necessity for inpatient admission and deny payment.

On the other hand, if overcoding occurs because the clinical criteria for a specific diagnosis have not been met, Medicare will take action to recover the overpayment, leveling penalties and sanctions. (For more information on Medicare’s Recovery Audit Contractor program, dubbed “Medicare’s repo men” by Dr. Pinson, see “Take Proactive Approach to Recovery Audit Contractors,” p. 28.)

Lack of specificity also hampers reimbursement for professional fees, says Barb Pierce, CCS-P, ACS-EM, president of Barb Pierce Coding and Consulting Inc. of West Des Moines, Iowa. “Unfortunately,” she observes, “the code isn’t just based on decision-making, which is why physicians went to school for all those years. The guidelines [Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services] mandate that if you forget one little bullet in history or examination, even if you’ve got the riskiest, highest-level, decision-making patient in front of you, that could pull down the whole code selection.”1

How costly might such small mistakes be for an HM group? According to the State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data survey, internal-medicine hospitalists generate a median of 1.86 work relative value units (wRVUs) per encounter, and collect $45.57 per wRVU.2 If a hospitalist has 2,200 encounters per year and averages only 1.65 wRVUs per encounter, improving documentation and coding performance could add an additional 0.21 wRVUs, meeting the national average. Multiplying those 2,200 encounters by the national average of 1.86, the hospitalist could potentially add an additional 462 wRVUs for the year. Such documentation improvement—up to the national average—would equate to $21,053 in additional billed revenue without increasing the physician’s overall workload.

Dr. Pinson explains that physicians often perceive their time constraints as so severe that they’d be hard pressed to find the time to learn about documentation and coding. But he maintains that even short seminars yield “a huge amount of information that would astound [hospitalists], in terms of usefulness for their own clinical practices.”

Barriers to the Coding Mindset

Most hospitalists receive little or no training in documentation and coding during medical school or residency. The lack of education is further complicated because there are several coding sets healthcare providers must master, each with different rules governing assignment of diagnoses and levels of care (see “Coding Sets: Separate but Overlapping,” above).

Inexperience with coding guidelines can lead to mismatches. Nelly Leon-Chisen, RHIA, director of coding and classification for the American Hospital Association (AHA), gives one example: The ICD-9-CM Official Coding Guideline stipulates that coders cannot assign diagnosis codes based on lab results.3 So although it might appear intuitive to a physician that repeated blood sugars and monitoring of insulin levels indicate a patient has diabetes, the coder cannot assign the diagnosis unless it’s explicitly stated in the record.

Some physicians could simply be using outmoded terminology, such as “renal insufficiency” instead of “acute renal failure,” Dr. Pinson notes. If hospitalists learn to focus on evidence-based clinical criteria to support the codes, it leads to more effective care, he says.

The nature of hospitalist programs might not lend itself to efficient revenue-cycle processes for their own professional billing, says Jeri Leong, RN, CPC, CPC-H, president and CEO of Honolulu-based Healthcare Coding Consultants of Hawaii. If the HM group contracts with several hospitals, the hospitalists will be together rarely as a group, “so they don’t have the luxury of sitting down together with their billers to get important feedback and coding updates,” she says.

Leong’s company identifies missed charges, for instance, when charge tags from different shifts do not get married together (Hospitalist A might round on the patient in the morning and turn in a charge tag; Hospitalist B might do a procedure in the afternoon, but the two tags do not get combined). Examples such as these, she says, “can be an issue from a compliance perspective, and can leave money on the table.”

One of the problems Kathy DeVault, RHIA, CCS, CCS-P, manager of professional practice resources for the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA), sees is a lack of continuity between initial admitting diagnosis and discharge summaries. For example, a hospitalist might admit a patient for acute renal failure—the correct diagnosis—and be able to reverse the condition fairly quickly, especially if the failure is due to dehydration.

The patient, whose issue is resolved, could be discharged by an attending physician who does not note the acute diagnosis in the summary. “That acute condition disappears, and the RAC auditor may then challenge the claim for payment,” DeVault says.

The Remedies

While physicians might think that they don’t have the time to acquire coding education, there could be other incentives coming down the pike. Dr. Pinson has noticed that hospitals are beginning to incorporate documentation accuracy into their contractual reimbursement formulas.

Documentation fixes vary according to domain. A hospital’s clinical documentation specialists can query physicians for clarity and detail in their notes; for instance, a diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF) must be accompanied by additional documentation stating whether the CHF is acute or chronic, and whether it is systolic or diastolic.

Many hospitals have instituted clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs, sometimes called clinical documentation integrity programs, to address documentation discrepancies. CDI programs are essential to hospitals’ financial survival, Dr. Pinson says, and hospitalists are ideally positioned to join those efforts.

“[The hospitalists] are the most important people to the hospital in all of this,” he says. “They’re at the center of this whirlpool. If you have these skills, your value to the hospital and to your group is greatly enhanced.” (Visit the-hospitalist.org to listen to Dr. Pinson discuss HM’s role in documentation improvement.)

Leon-Chisen also says that the relationship between coders and physicians should be collaborative. “If it’s adversarial, nobody wins,” she points out, adding that CDI programs present an opportunity for mutual education.

Conducting audits of the practice’s documentation and coding can identify coding strengths and weaknesses, says Pierce, who is faculty for SHM’s billing and coding pre-course and regularly consults with hospitalist groups. Audits are helpful, she says, not just for increasing group revenue, but for compliance reasons as well. “You need to know what you’re doing well, and what you’re not doing quite so well, and get it fixed internally before an entity like Medicare discovers it,” she says.

It’s no doubt difficult for a busy HM group to stay on top of annual coding updates and changes to guidelines for reporting their services, Leong notes. Her company has worked with many hospitalist groups over the years, offering coding workshops, “back end” audits, and real-time feedback of E/M and CPT coding choices. If all of the hospitalists in a group cannot convene simultaneously, Leong provides the feedback (in the form of a scorecard) to the group’s physician champion, who becomes the lead contact to help those physicians who struggle more with their coding. (Leong talks more about real-time feedback and capturing CPT and E/M codes at the-hospitalist.org.)

In lieu of hiring professional coders, some HM groups use electronic coding devices. The software could be a standalone product, or it could interface with other products, such as electronic medical records (EMRs). These programs assist with a variety of coding-related activities, such as CPT or ICD-9 lookups, or calculation of E/M key components with assignment of an appropriate level of billing. Leong, however, cautions too much reliance on technology.

“While these devices can be accurate, compact, and convenient, it’s important to maintain a current [software] subscription to keep abreast of updates to the code sets, which occur sometimes as often as quarterly,” she says.

Pierce adds that coding tools should be double-checked against an audit tool. She has sometimes found discrepancies when auditing against an EMR product that assigns the E/M level.

Attitude Adjustment

Coding experts emphasize that physicians need not worry about mastering coding manuals, but they should forge relationships with both their hospital’s billers and the coders for their practice.

Dr. Nweke took advantage of coding and billing workshops offered by her group, HMG, and through the seminars began to understand what a DRG meant not just for her hospital but for her own evaluations and the expansion of her HM group, too. “Now, when I get questions from billers and coders, I try to answer them quickly,” she says. “I don’t look upon them as the enemy, but rather as people who are helping me document appropriately, so I don’t get audited by Medicare. I think the way you view the coders and billers definitely affects your willingness to learn.”

Dr. Nweke also takes a broader view of her role as a hospitalist. “You are there to take care of patients and assist with transitioning them in and out of the hospital, but you’re also there to ensure that the hospital remains afloat financially,” she says. “Your documentation plays a huge role in that. We have a huge contribution to make.”

The patient gains, too, says Leon-Chisen, who explains that documentation should be as accurate as possible “because someone else—the patient’s primary physician—will be taking over care of that patient and needs to understand what happened in the hospital.”

“The bottom line,” Dr. Pinson says, “is that we need accurate documentation that can be correctly coded to reflect the true complexity of care and severity of illness. If we do that, good things will follow.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/Downloads/MASTER1.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2011.

- State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. Society of Hospital Medicine and Medical Group Management Association; Philadelphia and Englewood, Colo.; 2010.

- ICD-9-CM Official Coding Guidelines. CMS and National Center for Health Statistics; Washington, D.C.; 2008. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/cpt/icd9cm_coding_guidelines_08_09_full.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2011.