User login

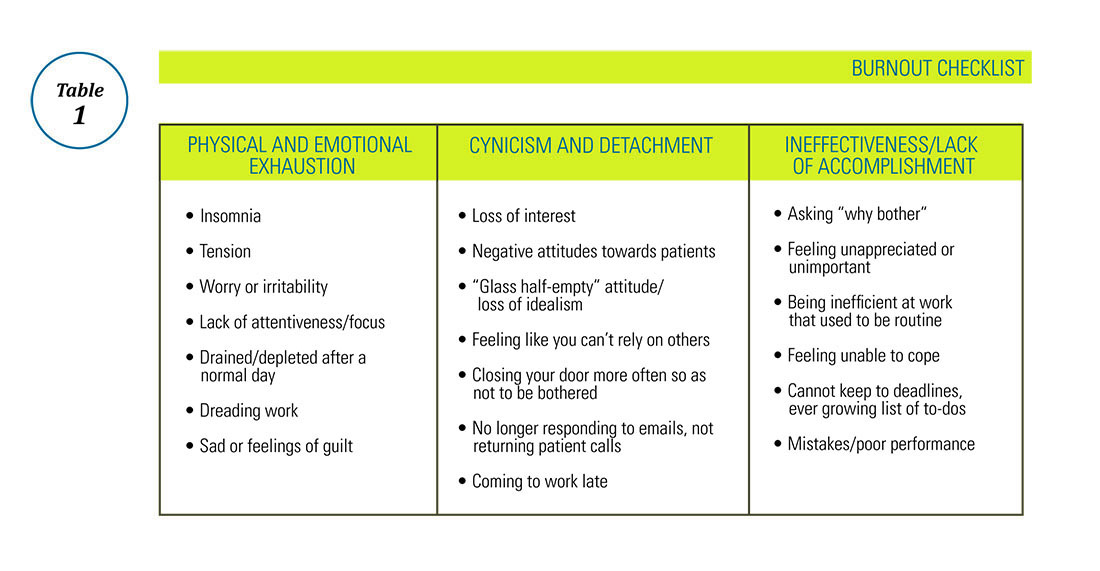

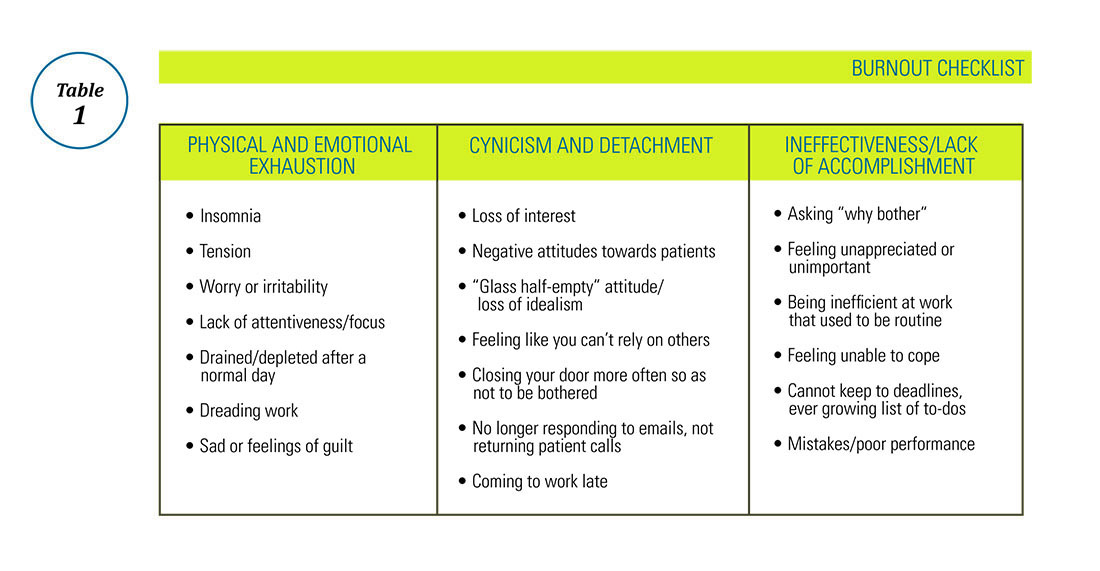

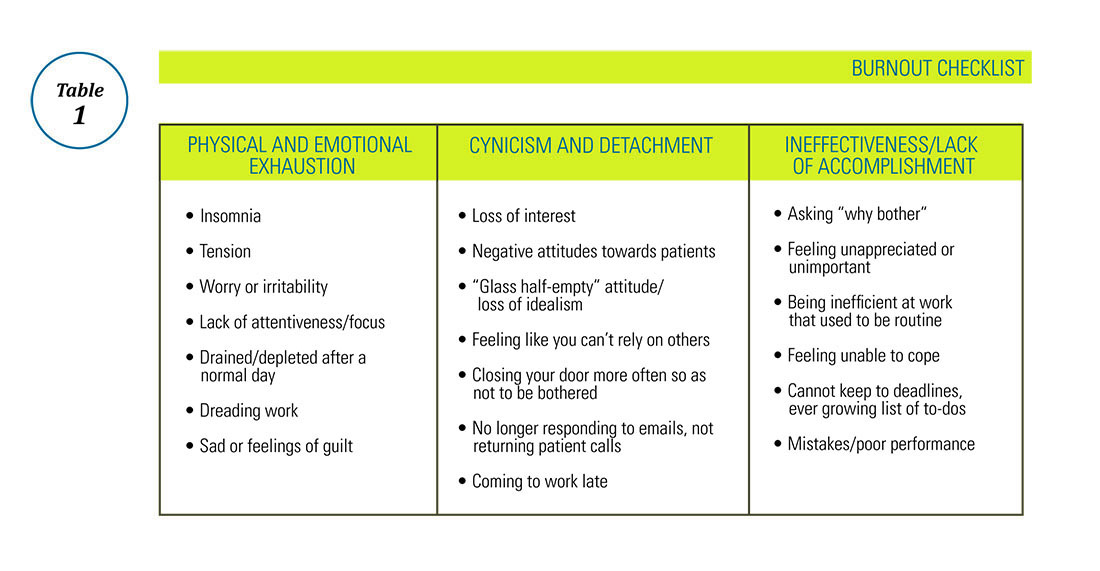

Physician burnout is a growing epidemic, particularly in the early careers of gastroenterologists. Up to 50% of new physicians and trainees experience burnout with the first 3 years of independent practice.1 The negative consequences of burnout are well known – medical errors, depression, substance abuse, and even suicide.2,3 To meet criteria for burnout syndrome (Table 1), one must have two of three core symptoms, often experienced as phases: 1) physical and emotional exhaustion; 2) cynicism and detachment; and 3) feelings of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.4

Emotional exhaustion, one of the earliest symptoms of burnout syndrome was reported to be as high as 63% among gastroenterologists in a survey study I conducted with colleagues a few years ago.5 Similar findings are noted amongst colorectal surgeons.6 We also noted in our study that burnout levels were highest in junior versus senior attendings, with junior attendings reporting more stress related to performing endoscopies and making split-second decisions. Interventional endoscopists may have been disproportionately affected by the latter, reporting that they were more likely to think about possible mistakes they made after work, have difficulty sleeping due to thinking about their day, and have difficulty separating work and personal life.5 Male and female physicians may progress through the phases of burnout differently, with men being more likely to experience cynicism and depersonalization first, followed by fatigue. Men may also not necessarily experience the third phase of feeling ineffective, which can be particularly dangerous because they will continue to push until there is a serious consequence. Women tend to go through all three phases of burnout beginning with emotional exhaustion, with a more rapid progression through the cynicism phase, and may end up spending the majority of their time feeling ineffective and limited in their accomplishments, a recipe for leaving medicine entirely.7

Prevention of burnout through self-compassion

Even though it may sometimes be easy to forget, most of us chose medicine as our profession because of our inherent compassion towards others and desire to care for those in need. But have we properly learned how to apply that same compassion to ourselves?

Self-compassion is one of the primary qualities of a happy, flourishing, resilient individual.8 Self-compassion is a psychological skill that can be applied to feelings of inadequacy, failure, or lack of control and includes: 1) self-kindness, 2) belief in a common humanity, and 3) mindfulness.8

Are you self-compassionate? Take a quiz!

Self-kindness requires us to treat ourselves as kindly as we would a friend or patient in the same situation. We must consciously choose not to use harsh, self-critical language when we make mistakes. We are taught not to berate our trainees for mistakes in the clinical setting – we can be taught not to berate ourselves for shortcomings as well. Self-kindness also requires that we provide ourselves with sympathy when we experience disappointments through no fault of our own (e.g. despite all my best efforts, this clinical initiative failed) and give ourselves the opportunity to nurture and soothe ourselves when we experience pain.6 Belief in a common humanity fosters engagement with others, recognizing that nobody is perfect and that others suffer as well. Isolating ourselves because we feel ashamed, embarrassed, or “crazy” in our experience of a situation only increases our suffering. As we engage with others, we are able to view things from a different perspective and also recognize that others around us have problems too. Indeed, social support may be one of the best buffers against burnout, particularly cynicism.12 A recent meta-analysis concluded that a combination of institutional engagement techniques including reduced hours and support groups as well as access to individual behavioral techniques such as mindfulness could reduce or prevent burnout.13

I have previously commented on the practice of mindfulness in the AGA Community forums and, as a potentially stand-alone component of self-compassion training,14 recommend it here as well. In addition to traditional mindfulness-based stress-reduction courses and mindfulness meditation practice found in many hospitals and community centers, individual meditation focused on loving kindness or gratitude as well as mindful exercises such as writing a self-compassionate letter or statements to yourself can be used to offset burnout in daily life.15 From the perspective of reducing burnout, mindfulness allows us to look at our feelings of cynicism, exhaustion, and inadequacy without judgment, to view them as symptoms rather than ugly truths about ourselves and that rather than avoid or suppress these feelings, to be mindful and compassionate toward them.

Finally, in the spirit of self-compassion, we must not judge ourselves for needing the help of others to navigate adversity – whether that support comes from our personal or professional life, or is provided by a mental health professional, we deserve to be taken care of as much as our patients do.

For more information, please visit the following, helpful resources: www.CenterForMSC.org, www.Self-Compassion.org, and www.MindfulSelfCompassion.org.

Dr. Keefer is director, psychobehavioral research, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, division of gastroenterology, New York, N.Y.

References

1. West C.P., Shanafelt T.D., Kolars J.C. JAMA. 2011;306[9]:952-60.

2. Maslach C., Leiter M.P. World Psychiatry. 2016;15[2]:103-11.

3. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Kivimaki M., et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48[10]:1023-30.

4. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Isometsa E., et al. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41[1]:11-7.

5. Farber B.A. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56[5]:589-94.

6. Keswani R.N., Taft T.H., Cote G.A., Keefer L. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106[10]:1734-40.

7. Sharma A., Sharp D.M., Walker L.G., Monson J.R. Psychooncology. 2008;17[6]:570-6.

8. Houkes I., Winants Y., Twellaar M., Verdonk P. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:240.

9. Neff K.D. Hum Dev. 2009;52[4]:211-4.

10. de Vente W., van Amsterdam J.G., Olff M., Kamphuis J.H., Emmelkamp P.M. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:431725.

11. Rockliff H., Karl A., McEwan K., Gilbert J., Matos M., Gilbert P. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on ‘compassion focused imagery’. Emotion. 2011;11[6]:1388-96.

12. Porges S.W. Biol Psychol. 2007;74[2]:301-7.

13. Breines J.G., Chen S. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38[9]:1133-43.

14. Heffernan M., Quinn G.M.T., Sister R.M., Fitzpatrick JJ. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16[4]:366-73.

15. Crocker J., Canevello A. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95[3]:555-75.

16. Thompson G., McBride R.B., Hosford C.C., Halaas G. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28[2]:174-82.

17. Nie Z., Jin Y., He L., et al. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8[10]:19144-9.

18. West C.P., Dyrbye L.N., Erwin P.J., Shanafelt T.D. Lancet. 2016. Nov 5;388(10057)2272-81.

19. Luchterhand C., Rakel D., Haq C., et al. WMJ. 2015;114[3]:105-9.

20. Montero-Marin J., Tops M., Manzanera R, Piva Demarzo MM, Alvarez de Mon M, Garcia-Campayo J. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1895.

Physician burnout is a growing epidemic, particularly in the early careers of gastroenterologists. Up to 50% of new physicians and trainees experience burnout with the first 3 years of independent practice.1 The negative consequences of burnout are well known – medical errors, depression, substance abuse, and even suicide.2,3 To meet criteria for burnout syndrome (Table 1), one must have two of three core symptoms, often experienced as phases: 1) physical and emotional exhaustion; 2) cynicism and detachment; and 3) feelings of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.4

Emotional exhaustion, one of the earliest symptoms of burnout syndrome was reported to be as high as 63% among gastroenterologists in a survey study I conducted with colleagues a few years ago.5 Similar findings are noted amongst colorectal surgeons.6 We also noted in our study that burnout levels were highest in junior versus senior attendings, with junior attendings reporting more stress related to performing endoscopies and making split-second decisions. Interventional endoscopists may have been disproportionately affected by the latter, reporting that they were more likely to think about possible mistakes they made after work, have difficulty sleeping due to thinking about their day, and have difficulty separating work and personal life.5 Male and female physicians may progress through the phases of burnout differently, with men being more likely to experience cynicism and depersonalization first, followed by fatigue. Men may also not necessarily experience the third phase of feeling ineffective, which can be particularly dangerous because they will continue to push until there is a serious consequence. Women tend to go through all three phases of burnout beginning with emotional exhaustion, with a more rapid progression through the cynicism phase, and may end up spending the majority of their time feeling ineffective and limited in their accomplishments, a recipe for leaving medicine entirely.7

Prevention of burnout through self-compassion

Even though it may sometimes be easy to forget, most of us chose medicine as our profession because of our inherent compassion towards others and desire to care for those in need. But have we properly learned how to apply that same compassion to ourselves?

Self-compassion is one of the primary qualities of a happy, flourishing, resilient individual.8 Self-compassion is a psychological skill that can be applied to feelings of inadequacy, failure, or lack of control and includes: 1) self-kindness, 2) belief in a common humanity, and 3) mindfulness.8

Are you self-compassionate? Take a quiz!

Self-kindness requires us to treat ourselves as kindly as we would a friend or patient in the same situation. We must consciously choose not to use harsh, self-critical language when we make mistakes. We are taught not to berate our trainees for mistakes in the clinical setting – we can be taught not to berate ourselves for shortcomings as well. Self-kindness also requires that we provide ourselves with sympathy when we experience disappointments through no fault of our own (e.g. despite all my best efforts, this clinical initiative failed) and give ourselves the opportunity to nurture and soothe ourselves when we experience pain.6 Belief in a common humanity fosters engagement with others, recognizing that nobody is perfect and that others suffer as well. Isolating ourselves because we feel ashamed, embarrassed, or “crazy” in our experience of a situation only increases our suffering. As we engage with others, we are able to view things from a different perspective and also recognize that others around us have problems too. Indeed, social support may be one of the best buffers against burnout, particularly cynicism.12 A recent meta-analysis concluded that a combination of institutional engagement techniques including reduced hours and support groups as well as access to individual behavioral techniques such as mindfulness could reduce or prevent burnout.13

I have previously commented on the practice of mindfulness in the AGA Community forums and, as a potentially stand-alone component of self-compassion training,14 recommend it here as well. In addition to traditional mindfulness-based stress-reduction courses and mindfulness meditation practice found in many hospitals and community centers, individual meditation focused on loving kindness or gratitude as well as mindful exercises such as writing a self-compassionate letter or statements to yourself can be used to offset burnout in daily life.15 From the perspective of reducing burnout, mindfulness allows us to look at our feelings of cynicism, exhaustion, and inadequacy without judgment, to view them as symptoms rather than ugly truths about ourselves and that rather than avoid or suppress these feelings, to be mindful and compassionate toward them.

Finally, in the spirit of self-compassion, we must not judge ourselves for needing the help of others to navigate adversity – whether that support comes from our personal or professional life, or is provided by a mental health professional, we deserve to be taken care of as much as our patients do.

For more information, please visit the following, helpful resources: www.CenterForMSC.org, www.Self-Compassion.org, and www.MindfulSelfCompassion.org.

Dr. Keefer is director, psychobehavioral research, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, division of gastroenterology, New York, N.Y.

References

1. West C.P., Shanafelt T.D., Kolars J.C. JAMA. 2011;306[9]:952-60.

2. Maslach C., Leiter M.P. World Psychiatry. 2016;15[2]:103-11.

3. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Kivimaki M., et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48[10]:1023-30.

4. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Isometsa E., et al. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41[1]:11-7.

5. Farber B.A. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56[5]:589-94.

6. Keswani R.N., Taft T.H., Cote G.A., Keefer L. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106[10]:1734-40.

7. Sharma A., Sharp D.M., Walker L.G., Monson J.R. Psychooncology. 2008;17[6]:570-6.

8. Houkes I., Winants Y., Twellaar M., Verdonk P. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:240.

9. Neff K.D. Hum Dev. 2009;52[4]:211-4.

10. de Vente W., van Amsterdam J.G., Olff M., Kamphuis J.H., Emmelkamp P.M. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:431725.

11. Rockliff H., Karl A., McEwan K., Gilbert J., Matos M., Gilbert P. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on ‘compassion focused imagery’. Emotion. 2011;11[6]:1388-96.

12. Porges S.W. Biol Psychol. 2007;74[2]:301-7.

13. Breines J.G., Chen S. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38[9]:1133-43.

14. Heffernan M., Quinn G.M.T., Sister R.M., Fitzpatrick JJ. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16[4]:366-73.

15. Crocker J., Canevello A. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95[3]:555-75.

16. Thompson G., McBride R.B., Hosford C.C., Halaas G. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28[2]:174-82.

17. Nie Z., Jin Y., He L., et al. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8[10]:19144-9.

18. West C.P., Dyrbye L.N., Erwin P.J., Shanafelt T.D. Lancet. 2016. Nov 5;388(10057)2272-81.

19. Luchterhand C., Rakel D., Haq C., et al. WMJ. 2015;114[3]:105-9.

20. Montero-Marin J., Tops M., Manzanera R, Piva Demarzo MM, Alvarez de Mon M, Garcia-Campayo J. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1895.

Physician burnout is a growing epidemic, particularly in the early careers of gastroenterologists. Up to 50% of new physicians and trainees experience burnout with the first 3 years of independent practice.1 The negative consequences of burnout are well known – medical errors, depression, substance abuse, and even suicide.2,3 To meet criteria for burnout syndrome (Table 1), one must have two of three core symptoms, often experienced as phases: 1) physical and emotional exhaustion; 2) cynicism and detachment; and 3) feelings of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.4

Emotional exhaustion, one of the earliest symptoms of burnout syndrome was reported to be as high as 63% among gastroenterologists in a survey study I conducted with colleagues a few years ago.5 Similar findings are noted amongst colorectal surgeons.6 We also noted in our study that burnout levels were highest in junior versus senior attendings, with junior attendings reporting more stress related to performing endoscopies and making split-second decisions. Interventional endoscopists may have been disproportionately affected by the latter, reporting that they were more likely to think about possible mistakes they made after work, have difficulty sleeping due to thinking about their day, and have difficulty separating work and personal life.5 Male and female physicians may progress through the phases of burnout differently, with men being more likely to experience cynicism and depersonalization first, followed by fatigue. Men may also not necessarily experience the third phase of feeling ineffective, which can be particularly dangerous because they will continue to push until there is a serious consequence. Women tend to go through all three phases of burnout beginning with emotional exhaustion, with a more rapid progression through the cynicism phase, and may end up spending the majority of their time feeling ineffective and limited in their accomplishments, a recipe for leaving medicine entirely.7

Prevention of burnout through self-compassion

Even though it may sometimes be easy to forget, most of us chose medicine as our profession because of our inherent compassion towards others and desire to care for those in need. But have we properly learned how to apply that same compassion to ourselves?

Self-compassion is one of the primary qualities of a happy, flourishing, resilient individual.8 Self-compassion is a psychological skill that can be applied to feelings of inadequacy, failure, or lack of control and includes: 1) self-kindness, 2) belief in a common humanity, and 3) mindfulness.8

Are you self-compassionate? Take a quiz!

Self-kindness requires us to treat ourselves as kindly as we would a friend or patient in the same situation. We must consciously choose not to use harsh, self-critical language when we make mistakes. We are taught not to berate our trainees for mistakes in the clinical setting – we can be taught not to berate ourselves for shortcomings as well. Self-kindness also requires that we provide ourselves with sympathy when we experience disappointments through no fault of our own (e.g. despite all my best efforts, this clinical initiative failed) and give ourselves the opportunity to nurture and soothe ourselves when we experience pain.6 Belief in a common humanity fosters engagement with others, recognizing that nobody is perfect and that others suffer as well. Isolating ourselves because we feel ashamed, embarrassed, or “crazy” in our experience of a situation only increases our suffering. As we engage with others, we are able to view things from a different perspective and also recognize that others around us have problems too. Indeed, social support may be one of the best buffers against burnout, particularly cynicism.12 A recent meta-analysis concluded that a combination of institutional engagement techniques including reduced hours and support groups as well as access to individual behavioral techniques such as mindfulness could reduce or prevent burnout.13

I have previously commented on the practice of mindfulness in the AGA Community forums and, as a potentially stand-alone component of self-compassion training,14 recommend it here as well. In addition to traditional mindfulness-based stress-reduction courses and mindfulness meditation practice found in many hospitals and community centers, individual meditation focused on loving kindness or gratitude as well as mindful exercises such as writing a self-compassionate letter or statements to yourself can be used to offset burnout in daily life.15 From the perspective of reducing burnout, mindfulness allows us to look at our feelings of cynicism, exhaustion, and inadequacy without judgment, to view them as symptoms rather than ugly truths about ourselves and that rather than avoid or suppress these feelings, to be mindful and compassionate toward them.

Finally, in the spirit of self-compassion, we must not judge ourselves for needing the help of others to navigate adversity – whether that support comes from our personal or professional life, or is provided by a mental health professional, we deserve to be taken care of as much as our patients do.

For more information, please visit the following, helpful resources: www.CenterForMSC.org, www.Self-Compassion.org, and www.MindfulSelfCompassion.org.

Dr. Keefer is director, psychobehavioral research, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, division of gastroenterology, New York, N.Y.

References

1. West C.P., Shanafelt T.D., Kolars J.C. JAMA. 2011;306[9]:952-60.

2. Maslach C., Leiter M.P. World Psychiatry. 2016;15[2]:103-11.

3. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Kivimaki M., et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48[10]:1023-30.

4. Ahola K., Honkonen T., Isometsa E., et al. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41[1]:11-7.

5. Farber B.A. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56[5]:589-94.

6. Keswani R.N., Taft T.H., Cote G.A., Keefer L. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106[10]:1734-40.

7. Sharma A., Sharp D.M., Walker L.G., Monson J.R. Psychooncology. 2008;17[6]:570-6.

8. Houkes I., Winants Y., Twellaar M., Verdonk P. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:240.

9. Neff K.D. Hum Dev. 2009;52[4]:211-4.

10. de Vente W., van Amsterdam J.G., Olff M., Kamphuis J.H., Emmelkamp P.M. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:431725.

11. Rockliff H., Karl A., McEwan K., Gilbert J., Matos M., Gilbert P. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on ‘compassion focused imagery’. Emotion. 2011;11[6]:1388-96.

12. Porges S.W. Biol Psychol. 2007;74[2]:301-7.

13. Breines J.G., Chen S. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38[9]:1133-43.

14. Heffernan M., Quinn G.M.T., Sister R.M., Fitzpatrick JJ. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16[4]:366-73.

15. Crocker J., Canevello A. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95[3]:555-75.

16. Thompson G., McBride R.B., Hosford C.C., Halaas G. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28[2]:174-82.

17. Nie Z., Jin Y., He L., et al. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8[10]:19144-9.

18. West C.P., Dyrbye L.N., Erwin P.J., Shanafelt T.D. Lancet. 2016. Nov 5;388(10057)2272-81.

19. Luchterhand C., Rakel D., Haq C., et al. WMJ. 2015;114[3]:105-9.

20. Montero-Marin J., Tops M., Manzanera R, Piva Demarzo MM, Alvarez de Mon M, Garcia-Campayo J. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1895.