User login

A protocol of immediate angiography provided no mortality benefit over a strategy or delayed or more selective angiography among patients resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and without ST-segment elevation, new randomized results show.

“Among patients with resuscitated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of possible cardiac origin, with shockable and nonshockable arrest rhythm and no ST-elevation, a strategy of immediate, unselected coronary angiography was not found to be beneficial over a delayed and selective approach with regard to the 30-day risk of all-cause death,” concluded principal investigator Steffen Desch, MD, University of Leipzig (Germany) Heart Center.

The results support previous results of the Coronary Angiography after Cardiac Arrest (COACT) trial, in patients with shockable rhythms, which also showed no differences in clinical outcomes between immediate and delayed coronary angiography at both 90 days and 1 year, he noted.

“What the clinicians wanted to know is, is it really necessary to get up at 3 a.m. in the morning to perform a coronary angiography on these patients, and that’s certainly out,” Dr. Desch said in an interview. “So, there’s really no room for this strategy anymore. You can take your time and wait a day or 2.”

These findings, from the TOMAHAWK trial, were presented Aug. 29 at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Larger group without ST-segment elevation

Prognosis after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is extremely poor, with an overall survival rate of less than 10%, Dr. Desch noted. “Actually, only 20% make it to the hospital; the vast majority of these patients die out in the field, so there’s really a great need in improving treatment.”

Acute coronary syndrome accounts for up to 60% of out-of-hospital arrests in which a cardiac cause has been identified, the authors wrote in their report. ST-segment elevation on postresuscitation electrocardiography “has good positive predictive value” for acute coronary lesions triggering the arrest, but in the far larger subgroup of patients without ST-segment elevation, “the spectrum of underlying causes is considerably broader and includes both cardiac and noncardiac causes.”

In patients with myocardial infarction, early revascularization would prevent negative consequences of myocardial injury, but unselected early coronary angiography would put patients not having an MI at unnecessary risk for procedural complications or delay in the diagnosis of the actual cause of their arrest, they noted.

In this trial, the researchers randomly assigned 554 patients from 31 sites in Germany and Denmark who were successfully resuscitated after cardiac arrest of possible cardiac origin to immediate transfer for coronary angiography or to initial intensive care assessment with delayed or selective angiography after a minimum delay of at least 1 day.

In the end, the average delay in this arm was 2 days, Dr. Desch noted. If the clinical course indicated that a coronary cause was unlikely, angiography might not be performed at all in this group.

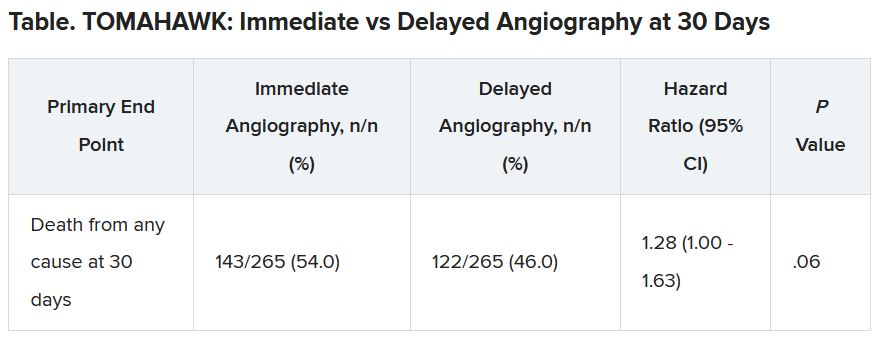

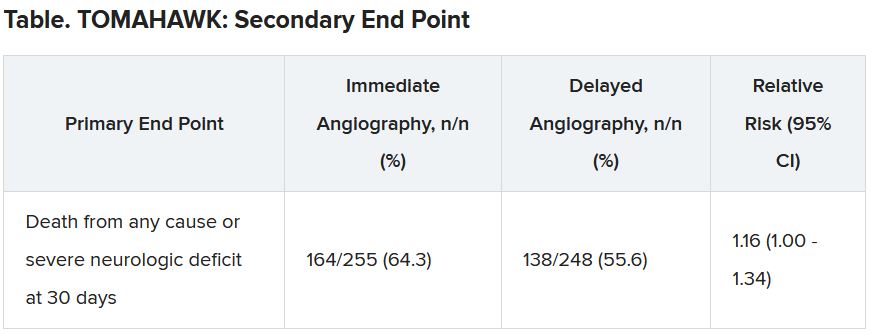

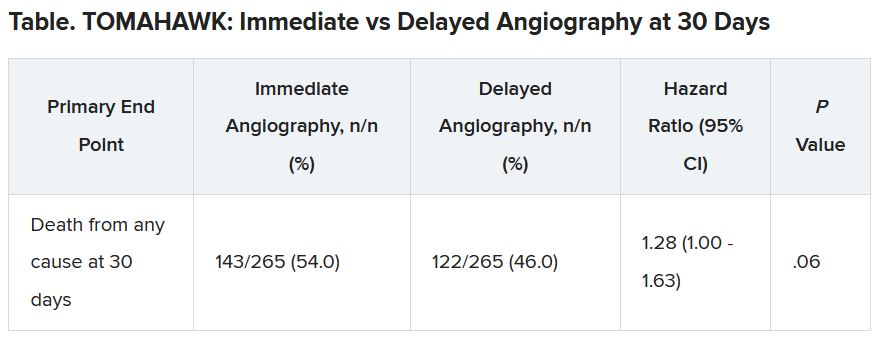

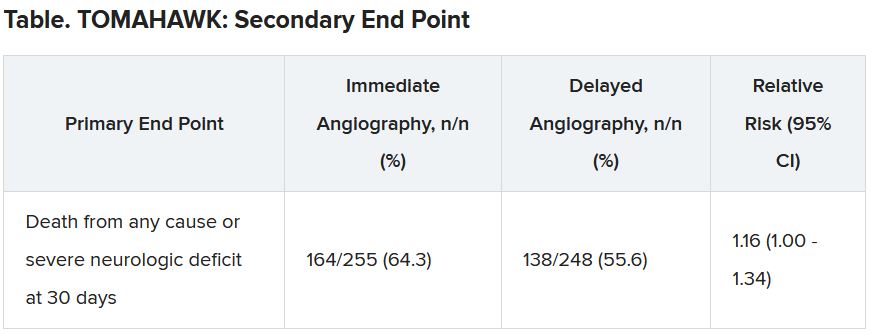

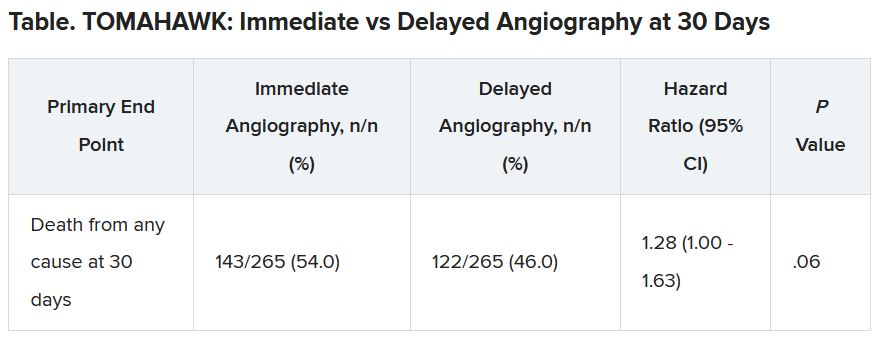

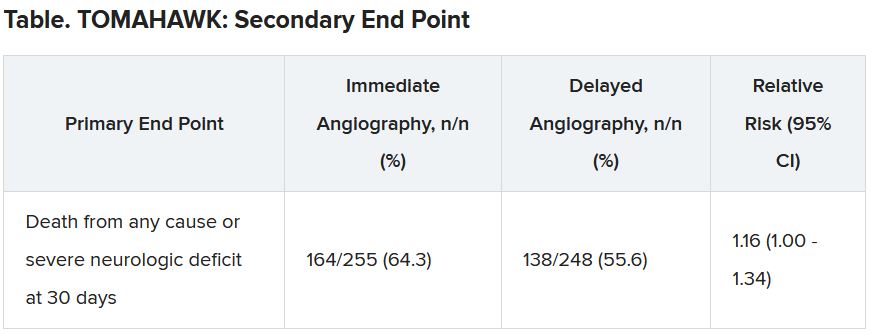

No patient had ST-segment elevation on postresuscitation electrocardiography. The primary endpoint was death from any cause at 30 days; secondary end points were death from any cause or severe neurologic deficit at 30 days.

Results showed that 95% of patients in the immediate angiography group actually underwent the procedure, compared with 62% of those in the delayed group, a finding that was “logical” given the study design, he said.

At 30 days, 54% of patients in the immediate angiography group and 46% in the delayed group had died, a nonsignificant difference (P = .06). Because the researchers had performed an interim analysis, Dr. Desch explained, the final P value for significance in this trial was not .05, but rather .034, to account for multiple comparisons.

The secondary end point of death from any cause or severe neurologic deficit at 30 days “was actually nominally significant in favor of the delayed group,” he said. “So, this is not corrected for multiple testing, it’s just a hypothesis that’s in the room, but it’s certainly worthy of discussion that the immediate strategy might actually cause harm.”

There was no difference between the groups in peak release of myocardial enzymes, or any other safety end points, including bleeding, stroke, or renal failure, Dr. Desch said.

Further analyses showed no large differences between subgroups, including age, diabetes, first monitored rhythm, confirmed MI as the trigger of the arrest, sex, and the time from cardiac arrest to the return of spontaneous circulation, he noted.

Opportunity to minimize harm

Discussant for the results during the presentation was Susanna Price, MBBS, PhD, Royal Brompton Hospital, London.

Dr. Price concluded: “What this means for me, is it gives me information that’s useful regarding the opportunity to minimize harm, which is a lot of what critical care is about, so we don’t necessarily now have to move these patients very acutely when they’ve just come in through the ED [emergency department]. It has implications for resource utilization, but also implications for mobilizing patients around the hospital during COVID-19.”

It’s also important to note that coronary angiography was still carried out in certain patients, “so we still have to have that dialogue with our interventional cardiologists for certain patients who may need to go to the cath lab, and what it should now allow us to do is give appropriate focus to how to manage these patients when they come in to the ED or to our ICUs [intensive care units],” she said.

Dr. Price added, though, that perhaps “the most important slide” in the presentation was that showing 90% of these patients had a witnessed cardiac arrest, “and yet a third of these patients, 168 of them, had no bystander CPR at all.”

She pointed to the “chain of survival” after cardiac arrest, of which Charles D. Deakin, MD, University Hospital Southampton (England), wrote that “not all links are equal.”

“Early recognition and calling for help, early CPR, early defibrillation where appropriate are very, very important, and we need to be addressing all of these, as well as what happens in the cath lab and after admission,” Dr. Price said.

This research was funded by the German Center for Cardiovascular Research. Dr. Desch and Dr. Price reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A protocol of immediate angiography provided no mortality benefit over a strategy or delayed or more selective angiography among patients resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and without ST-segment elevation, new randomized results show.

“Among patients with resuscitated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of possible cardiac origin, with shockable and nonshockable arrest rhythm and no ST-elevation, a strategy of immediate, unselected coronary angiography was not found to be beneficial over a delayed and selective approach with regard to the 30-day risk of all-cause death,” concluded principal investigator Steffen Desch, MD, University of Leipzig (Germany) Heart Center.

The results support previous results of the Coronary Angiography after Cardiac Arrest (COACT) trial, in patients with shockable rhythms, which also showed no differences in clinical outcomes between immediate and delayed coronary angiography at both 90 days and 1 year, he noted.

“What the clinicians wanted to know is, is it really necessary to get up at 3 a.m. in the morning to perform a coronary angiography on these patients, and that’s certainly out,” Dr. Desch said in an interview. “So, there’s really no room for this strategy anymore. You can take your time and wait a day or 2.”

These findings, from the TOMAHAWK trial, were presented Aug. 29 at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Larger group without ST-segment elevation

Prognosis after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is extremely poor, with an overall survival rate of less than 10%, Dr. Desch noted. “Actually, only 20% make it to the hospital; the vast majority of these patients die out in the field, so there’s really a great need in improving treatment.”

Acute coronary syndrome accounts for up to 60% of out-of-hospital arrests in which a cardiac cause has been identified, the authors wrote in their report. ST-segment elevation on postresuscitation electrocardiography “has good positive predictive value” for acute coronary lesions triggering the arrest, but in the far larger subgroup of patients without ST-segment elevation, “the spectrum of underlying causes is considerably broader and includes both cardiac and noncardiac causes.”

In patients with myocardial infarction, early revascularization would prevent negative consequences of myocardial injury, but unselected early coronary angiography would put patients not having an MI at unnecessary risk for procedural complications or delay in the diagnosis of the actual cause of their arrest, they noted.

In this trial, the researchers randomly assigned 554 patients from 31 sites in Germany and Denmark who were successfully resuscitated after cardiac arrest of possible cardiac origin to immediate transfer for coronary angiography or to initial intensive care assessment with delayed or selective angiography after a minimum delay of at least 1 day.

In the end, the average delay in this arm was 2 days, Dr. Desch noted. If the clinical course indicated that a coronary cause was unlikely, angiography might not be performed at all in this group.

No patient had ST-segment elevation on postresuscitation electrocardiography. The primary endpoint was death from any cause at 30 days; secondary end points were death from any cause or severe neurologic deficit at 30 days.

Results showed that 95% of patients in the immediate angiography group actually underwent the procedure, compared with 62% of those in the delayed group, a finding that was “logical” given the study design, he said.

At 30 days, 54% of patients in the immediate angiography group and 46% in the delayed group had died, a nonsignificant difference (P = .06). Because the researchers had performed an interim analysis, Dr. Desch explained, the final P value for significance in this trial was not .05, but rather .034, to account for multiple comparisons.

The secondary end point of death from any cause or severe neurologic deficit at 30 days “was actually nominally significant in favor of the delayed group,” he said. “So, this is not corrected for multiple testing, it’s just a hypothesis that’s in the room, but it’s certainly worthy of discussion that the immediate strategy might actually cause harm.”

There was no difference between the groups in peak release of myocardial enzymes, or any other safety end points, including bleeding, stroke, or renal failure, Dr. Desch said.

Further analyses showed no large differences between subgroups, including age, diabetes, first monitored rhythm, confirmed MI as the trigger of the arrest, sex, and the time from cardiac arrest to the return of spontaneous circulation, he noted.

Opportunity to minimize harm

Discussant for the results during the presentation was Susanna Price, MBBS, PhD, Royal Brompton Hospital, London.

Dr. Price concluded: “What this means for me, is it gives me information that’s useful regarding the opportunity to minimize harm, which is a lot of what critical care is about, so we don’t necessarily now have to move these patients very acutely when they’ve just come in through the ED [emergency department]. It has implications for resource utilization, but also implications for mobilizing patients around the hospital during COVID-19.”

It’s also important to note that coronary angiography was still carried out in certain patients, “so we still have to have that dialogue with our interventional cardiologists for certain patients who may need to go to the cath lab, and what it should now allow us to do is give appropriate focus to how to manage these patients when they come in to the ED or to our ICUs [intensive care units],” she said.

Dr. Price added, though, that perhaps “the most important slide” in the presentation was that showing 90% of these patients had a witnessed cardiac arrest, “and yet a third of these patients, 168 of them, had no bystander CPR at all.”

She pointed to the “chain of survival” after cardiac arrest, of which Charles D. Deakin, MD, University Hospital Southampton (England), wrote that “not all links are equal.”

“Early recognition and calling for help, early CPR, early defibrillation where appropriate are very, very important, and we need to be addressing all of these, as well as what happens in the cath lab and after admission,” Dr. Price said.

This research was funded by the German Center for Cardiovascular Research. Dr. Desch and Dr. Price reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A protocol of immediate angiography provided no mortality benefit over a strategy or delayed or more selective angiography among patients resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and without ST-segment elevation, new randomized results show.

“Among patients with resuscitated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of possible cardiac origin, with shockable and nonshockable arrest rhythm and no ST-elevation, a strategy of immediate, unselected coronary angiography was not found to be beneficial over a delayed and selective approach with regard to the 30-day risk of all-cause death,” concluded principal investigator Steffen Desch, MD, University of Leipzig (Germany) Heart Center.

The results support previous results of the Coronary Angiography after Cardiac Arrest (COACT) trial, in patients with shockable rhythms, which also showed no differences in clinical outcomes between immediate and delayed coronary angiography at both 90 days and 1 year, he noted.

“What the clinicians wanted to know is, is it really necessary to get up at 3 a.m. in the morning to perform a coronary angiography on these patients, and that’s certainly out,” Dr. Desch said in an interview. “So, there’s really no room for this strategy anymore. You can take your time and wait a day or 2.”

These findings, from the TOMAHAWK trial, were presented Aug. 29 at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Larger group without ST-segment elevation

Prognosis after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is extremely poor, with an overall survival rate of less than 10%, Dr. Desch noted. “Actually, only 20% make it to the hospital; the vast majority of these patients die out in the field, so there’s really a great need in improving treatment.”

Acute coronary syndrome accounts for up to 60% of out-of-hospital arrests in which a cardiac cause has been identified, the authors wrote in their report. ST-segment elevation on postresuscitation electrocardiography “has good positive predictive value” for acute coronary lesions triggering the arrest, but in the far larger subgroup of patients without ST-segment elevation, “the spectrum of underlying causes is considerably broader and includes both cardiac and noncardiac causes.”

In patients with myocardial infarction, early revascularization would prevent negative consequences of myocardial injury, but unselected early coronary angiography would put patients not having an MI at unnecessary risk for procedural complications or delay in the diagnosis of the actual cause of their arrest, they noted.

In this trial, the researchers randomly assigned 554 patients from 31 sites in Germany and Denmark who were successfully resuscitated after cardiac arrest of possible cardiac origin to immediate transfer for coronary angiography or to initial intensive care assessment with delayed or selective angiography after a minimum delay of at least 1 day.

In the end, the average delay in this arm was 2 days, Dr. Desch noted. If the clinical course indicated that a coronary cause was unlikely, angiography might not be performed at all in this group.

No patient had ST-segment elevation on postresuscitation electrocardiography. The primary endpoint was death from any cause at 30 days; secondary end points were death from any cause or severe neurologic deficit at 30 days.

Results showed that 95% of patients in the immediate angiography group actually underwent the procedure, compared with 62% of those in the delayed group, a finding that was “logical” given the study design, he said.

At 30 days, 54% of patients in the immediate angiography group and 46% in the delayed group had died, a nonsignificant difference (P = .06). Because the researchers had performed an interim analysis, Dr. Desch explained, the final P value for significance in this trial was not .05, but rather .034, to account for multiple comparisons.

The secondary end point of death from any cause or severe neurologic deficit at 30 days “was actually nominally significant in favor of the delayed group,” he said. “So, this is not corrected for multiple testing, it’s just a hypothesis that’s in the room, but it’s certainly worthy of discussion that the immediate strategy might actually cause harm.”

There was no difference between the groups in peak release of myocardial enzymes, or any other safety end points, including bleeding, stroke, or renal failure, Dr. Desch said.

Further analyses showed no large differences between subgroups, including age, diabetes, first monitored rhythm, confirmed MI as the trigger of the arrest, sex, and the time from cardiac arrest to the return of spontaneous circulation, he noted.

Opportunity to minimize harm

Discussant for the results during the presentation was Susanna Price, MBBS, PhD, Royal Brompton Hospital, London.

Dr. Price concluded: “What this means for me, is it gives me information that’s useful regarding the opportunity to minimize harm, which is a lot of what critical care is about, so we don’t necessarily now have to move these patients very acutely when they’ve just come in through the ED [emergency department]. It has implications for resource utilization, but also implications for mobilizing patients around the hospital during COVID-19.”

It’s also important to note that coronary angiography was still carried out in certain patients, “so we still have to have that dialogue with our interventional cardiologists for certain patients who may need to go to the cath lab, and what it should now allow us to do is give appropriate focus to how to manage these patients when they come in to the ED or to our ICUs [intensive care units],” she said.

Dr. Price added, though, that perhaps “the most important slide” in the presentation was that showing 90% of these patients had a witnessed cardiac arrest, “and yet a third of these patients, 168 of them, had no bystander CPR at all.”

She pointed to the “chain of survival” after cardiac arrest, of which Charles D. Deakin, MD, University Hospital Southampton (England), wrote that “not all links are equal.”

“Early recognition and calling for help, early CPR, early defibrillation where appropriate are very, very important, and we need to be addressing all of these, as well as what happens in the cath lab and after admission,” Dr. Price said.

This research was funded by the German Center for Cardiovascular Research. Dr. Desch and Dr. Price reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.