User login

Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, affects more than 5 million Americans.1 Estimates suggest that by 2050, the prevalence could triple, reaching 13 to 16 million.1 To effectively care for patients with AD and their families, primary care providers need to be familiar with the latest evidence on all facets of care, from initial detection to patient management and end-of-life care.

This evidence-based review will help you toward that end by answering common questions regarding Alzheimer care, including whether routine screening is advisable, what tests should be ordered, which interventions (including nonpharmacologic options) are worth considering, and how best to counsel patients and families about end-of-life care.

ROUTINE SCREENING? STILL SUBJECT TO DEBATE

The key question regarding routine dementia screening in primary care is whether it improves outcomes. Advocates note that individuals with dementia may appear unimpaired during office visits and may not report symptoms due to lack of insight; they point out, too, that waiting for an event that makes cognitive impairment obvious (eg, driving mishap) is risky.2 Those who advocate routine screening also note that only about half of those who have dementia are ever diagnosed.3

Others, including the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), disagree. In its 2014 evidence review, the USPSTF indicated that there is “insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for cognitive impairment in older adults.”4

Mixed messages

The dearth of evidence is also reflected in the conflicting recommendations of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The ACA requires clinicians to assess cognitive function during Medicare patients’ annual wellness visits. CMS, however, instructs providers to screen for dementia only if observation or concerns raised by the patient or family suggest the possibility of impairment and does not recommend any particular test.5

Cost-effectiveness analyses also raise questions about the value of routine screening. Evidence suggests that screening 300 older patients will yield 39 positive results. But only about half of those will agree to a diagnostic evaluation, and no more than nine will ultimately be diagnosed with dementia. The estimated cost of identifying nine cases is nearly $40,000—all in the absence of a treatment to cure or stop the progression of the disorder.6

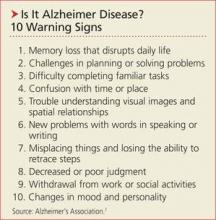

The bottom line: Evidence does not support routine dementia screening of older adults. When cognitive impairment is suspected, however, clinicians should conduct a diagnostic evaluation—and consider educating patients and families about the Alzheimer’s Association (AA)’s 10 Warning Signs of AD (see box, above).7 A longer version (www.alz.org/national/documents/checklist_10signs.pdf) outlines the cognitive changes that are characteristic of healthy aging and compares them to changes suggestive of early dementia.7

Next: How to proceed when you suspect AD >>

HOW TO PROCEED WHEN YOU SUSPECT AD

Step 1: Screening instrument. The first step in the diagnostic evaluation of a patient with suspected AD is to determine if, in fact, cognitive impairment is present. This can be assessed with in-office screening instruments, such as the Mini-Cog (http://bit.ly/1FwQAkG) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; http://bit.ly/18Djin5), among others.8

Step 2: Clinical evaluation. If observation and test results suggest cognitive impairment, the next step is to determine whether clinical findings are consistent with the diagnostic criteria for AD (see Table 1)9 developed by workgroups from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the AA in 2011. A work-up is necessary to identify conditions that can mimic dementia (eg, depression) and behaviors that suggest another type of dementia, such as frontotemporal or Lewy body dementia.10 Lab testing should be included to rule out potentially reversible causes of cognitive dysfunction (eg, hypothyroidism, vitamin D deficiency).

Step 3: Neuropsychologic evaluation. The NIA/AA recommends neuropsychologic testing when the brief cognitive tests, history, and clinical work-up are not sufficient for a definitive diagnosis of dementia.9 This generally involves a referral to a neuropsychologist, who conducts a battery of standardized tests to evaluate attention, memory, language, visual-spatial abilities, and executive functions, among others. Neuropsychologic testing can confirm the presence of cognitive impairment and aid in the differential diagnosis by comparing the patient’s performance in these domains with characteristic features of different dementia syndromes.

Step 4: Brain imaging with either CT or MRI can be included in the work-up for patients with suspected AD to rule out abnormalities (eg, metastatic cancer, hydrocephalus, or occult chronic subdural hematoma) that could be causing cognitive impairment.9,10 Clinical features that generally warrant brain imaging include onset of cognitive impairment before age 60; unexplained focal neurologic signs or symptoms; abrupt onset or rapid decline; and/or predisposing conditions (eg, cancer or anticoagulant treatment).10

The role of biomarkers and advanced brain imaging

Biomarkers that might provide confirmation of AD in patients who exhibit early symptoms of dementia have been studied extensively.11 The NIA/AA identified two categories of AD biomarkers

• Tests for β-amyloid deposition in the brain, including spinal fluid assays for β-amyloid (Aβ42) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans after IV injection of florbetapir or flutemetamol, which bind to amyloid in the brain; and

• Tests for neuronal degeneration, which would include spinal fluid assays for tau protein and PET scans after injection of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), which shows decreased uptake in patients with AD.9

Research reveals the promise of these biomarkers as diagnostic tools, particularly in patients with an atypical presentation of dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) that may be associated with early AD.12 (More on MCI in a moment.) However, the NIA/AA concluded that additional research is needed to validate these tests for routine diagnostic purposes. Medicare covers PET scans with FDG only for the differential diagnosis of AD versus frontotemporal dementia.13

Continue for mild cognitive impairment >>

MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: HOW LIKELY THAT IT WILL PROGRESS?

Along with diagnostic criteria for AD, the NIA/AA developed criteria for a symptomatic predementia phase of AD—often referred to as MCI.14 According to the workgroup, MCI is diagnosed when

1. The patient, an informant, or a clinician is concerned about the individual’s cognitive decline from previous levels of functioning

2. There is evidence of cognitive impairment, ideally through psychometric testing, revealing performance below expectation based on the patient’s age and education

3. The patient is able to maintain independent functioning in daily life, despite mild problems or the need for minimal assistance

4. There is no significant impairment in social or occupational functioning.14

Progression: Less likely than you might think

Patients with MCI are at risk for progression to overt dementia, with an overall annual conversion rate from MCI to dementia estimated at 10% to 15%.15,16 This estimate must be interpreted with caution, however, because most studies were conducted prior to the 2011 guidelines, when different diagnostic criteria were used. Observers have noted, too, that the numbers largely reflect data collected in specialty clinics and that community-based studies reveal substantially lower conversion rates (3% to 6% per year).16 In addition, evidence suggests that many patients with MCI demonstrate long-term stability or even reversal of deficits.17

While there is some consideration of the use of biomarkers and amyloid imaging tests to help determine which patients with MCI will progress to AD, practice guidelines do not currently recommend such testing and it is not covered by Medicare.

WHEN EVIDENCE INDICATES AN AD DIAGNOSIS

When faced with the need to communicate an AD diagnosis, follow the general recommendations for delivering any bad news or discouraging prognosis.

Prioritize and limit the information you provide, determining not only what the patient and family want to hear but also how much they are able to comprehend.

Confirm that the patient and family understand the information you’ve provided.

Offer emotional support and recommend additional resources (see Table 2).18

Given the progressive cognitive decline that characterizes AD, it is important to address the primary caregiver’s understanding of, and ability to cope with, the disease. It is also important to explore beliefs and attitudes regarding AD. Keep in mind that cultural groups tend to differ in their beliefs about the nature, cause, and appropriate management of AD, as well as the role of spirituality, help-seeking, and stigma.19,20

The progressive and ultimately fatal nature of AD also makes planning for the future a priority. Ideally, patients should be engaged in discussions regarding end-of-life care as early as possible, while they are still able to make informed decisions and express their preferences. Discussing end-of-life care can be overwhelming for newly diagnosed patients and their families, however, so it is important that you address issues—medical, financial, and legal planning, for example—that families should be considering.

Next: Medication for cognitive and behaviorial function >>

Drugs address cognitive and behavioral function

No currently available treatments can cure or significantly alter the progression of AD, but two classes of medications are used in an attempt to improve cognitive function. One is cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs), which potentiate acetylcholine synaptic transmission. The other is N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor blockers. Other classes of drugs are sometimes used to treat behavioral symptoms, such as agitation, aggression, mood disorders, and psychosis (eg, delusions, hallucinations).

Cognitive function. Results from studies of pharmacologic management of MCI vary widely, but recent reviews have found no convincing evidence that either ChEIs or NMDA receptor blockers have an effect on progression from MCI to dementia.21,22 Neither class is FDA-approved for treatment of MCI.

In patients with dementia, the effects of ChEIs and NMDA receptor blockers on cognition are statistically significant but modest and often of questionable clinical relevance.23 Nonetheless, among ChEIs, donepezil is approved by the FDA for mild, moderate, and severe dementia, and galantamine and rivastigmine are approved for mild and moderate dementia. There is no evidence that one ChEI is more effective than another,24 and the choice is often guided by cost, adverse effects, and health plan formularies. Memantine, the only FDA-approved NMDA receptor blocker, is approved for moderate to severe dementia and can be used alone or in combination with a ChEI.

If these drugs are used in an attempt to improve cognition in AD, guidelines recommend the following approach for initial therapy: Prescribe a ChEI for the mild stage, a ChEI plus memantine for the moderate stage, and memantine (with or without a ChEI) for the severe stage.25 The recommendations also include monitoring every six months.

There is no consensus about when to discontinue medication. Various published recommendations call for continuing treatment until the patient has “lost all cognitive and functional abilities;”22 until the patient’s MMSE score falls below 10 and there is no indication that the drug is having a “worthwhile effect;”21 or until he or she has reached stage 7 on the Reisberg Functional Assessment Staging scale, indicating nonambulatory status with speech limited to one to five words a day.10

Behavioral function. A variety of drugs are used to treat behavioral symptoms in AD. While not FDA-approved for this use, the most widely prescribed agents are second-generation antipsychotics (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone). The main effect of these drugs is often nothing more than sedation, and one large multisite clinical trial concluded that the adverse effects offset the benefits for patients with AD.26 Indeed, the FDA has issued an advisory on the use of second-generation antipsychotics in AD patients, stating that they are associated with increased mortality risk.27 The recently updated Beers Criteria strongly recommend avoiding these drugs for treatment of behavioral disturbances in AD unless nonpharmacologic options have failed and the patient is a threat to self or others.28

Because of the black-box warning that antipsychotics increase the risk for death, some clinicians have advocated obtaining informed consent prior to prescribing such medications.29 At the very least, when family or guardians are involved, a conversation about risks versus benefits should take place and be documented in the medical record.

Other drug classes are also sometimes used in an attempt to improve behavioral function, including antiseizure medications (valproic acid, carbamazepine), antidepressants (trazodone and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), and anxiolytics (benzodiazepines and buspirone). Other than their sedating effects, there is no strong evidence that these drugs are effective for treating dementia-related behavioral disorders. If used, caution is required due to potential adverse effects.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT IS "PROMISING"

A recent systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions for MCI evaluated exercise, training in compensatory strategies, and engagement in cognitively stimulating activities and found “promising but inconclusive” results. The researchers found that studies show mostly positive effects on cognition but have significant methodologic limitations.30 Importantly, there is no evidence of delayed or reduced conversion to dementia.

For patients who already have mild-to-moderate dementia, cognitive stimulation seems to help in the short term.31 There is also some evidence that exercise and occupational therapy may slow functional decline,32 but the effects are small to modest and their actual clinical significance (eg, the ability to delay institutionalization) is unclear. There is promising but preliminary evidence that cognitive rehabilitation (helping patients devise strategies to complete daily activities) may improve functioning in everyday life.33

While behavioral symptoms are often due to the dementia itself, it is important to identify and treat medical and environmental causes that may be contributing, such as infection, pain, and loud or unsafe environments. As noted before, nonpharmacologic treatments are generally preferred for behavioral problems and should be considered prior to drug therapy. Approaches that identify and modify both the antecedents and consequences of problem behaviors and increase pleasant events have empiric support for the management of behavioral symptoms.34 Interventions including massage therapy, aromatherapy, exercise, and music therapy may also be effective in the short term for agitated behavior.35

Caregivers should be encouraged to receive training in these strategies through organizations such as AA. Caregiver education and support can reduce caregivers’ distress and increase their self-efficacy and coping skills.36

Continue: Is it time for hospice? >>

END-OF-LIFE CARE MUST BE ADDRESSED

Perhaps the most important aspect of end-of-life care in AD is assuring that families (or health care proxies) understand that AD is a fatal illness, with most patients dying within four to eight years of diagnosis.1 Evidence indicates that patients whose proxies have a clear recognition of this are less likely to experience “burdensome” interventions such as parenteral therapy, emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and tube feedings in their last three months of life.37

Overall, decisions regarding discontinuing medical treatments in advanced AD should be made by balancing the likelihood of benefit with the potential for adverse effects.38 For example, the American Geriatrics Society recently recommended against feeding tubes because they often result in discomfort due to agitation, use of restraints, and worsening pressure ulcers.39

Unfortunately, only a minority of families receives straightforward information on the course and prognosis of AD, including the fact that patients eventually stop eating and that the natural cause of death is often an acute infection. Studies also show that patients with dementia are at risk for inadequate treatment of pain.40 Assuring adequate pain control is an essential component of end-of-life care.

Hospice. End-of-life care can often be improved with hospice care. This service is underused by patients with dementia, even though hospice care is available at no cost through Medicare. Hospice eligibility criteria for patients with AD are shown in Table 3.41,42

Next page: Prevention >>

FINALLY, A WORD ABOUT PREVENTION

Numerous risk factors have been associated with an increased risk for AD (see Table 4).2,3 Some, like age and genetics, are nonmodifiable, while others—particularly cardiovascular risk factors—can be modified.1 There are also factors associated with decreased risks—most notably, physical exercise and participation in cognitively stimulating activities.3 Identification of these factors has led to the hope that addressing them can prevent AD.

But association does not equal causation. In 2010, a report from the National Institutes of Health concluded that, although there are modifiable factors associated with AD, there is insufficient evidence that addressing any of them will actually prevent AD.43 In fact, there is good evidence that some of these factors (eg, statin therapy) are not effective in reducing the incidence of dementia and that others (eg, vitamin E and estrogen therapy) are potentially harmful.44

The absence of empirically supported preventive interventions does not mean, however, that we should disregard these risks and protective factors. Encouraging social engagement, for example, may improve both emotional health and quality of life. Addressing cardiovascular risk factors can reduce the rate of coronary and cerebrovascular disease, potentially including vascular dementia, even if it does not reduce the rate of AD.

Studies are evaluating the use of monoclonal antibodies with anti-amyloid properties for prevention of AD in individuals who have APOE ε4 genotypes or high amyloid loads on neuroimaging.45 It will be several years before results are available, however, and the outcome of these studies is uncertain, as the use of anti-amyloid agents for treating established dementia has not been effective.46,47

REFERENCES

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2013.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

2. Román GC, Nash DT, Fillit H. Translating current knowledge into dementia prevention. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:295-299.

3. Jak AJ. The impact of physical and mental activity on cognitive aging. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;10:273-291.

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening. Accessed March 21, 2015.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Guide to Medicare Preventive Services. 4th ed. 2011. www.curemd.com/fqhc/The%20Guide%20to%20Medicare%20Preventative%20Services%20for%20Physicans,%20Providers%20and%20Suppliers.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

6. Boustani M. Dementia screening in primary care: not too fast! J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1205-1207.

7. Alzheimer’s Association. Know the 10 signs: early detection matters. www.alz.org/national/documents/checklist_10signs.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

8. Cordell CB, Borson S, Boustani M, et al; Medicare Detection of Cognitive Impairment Workgroup. Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit in a primary care setting. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:141-150.

9. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263-269.

10. The American Geriatrics Society. A guide to dementia diagnosis and treatment. http://dementia.americangeriatrics.org/documents/AGS_PC_Dementia_Sheet_2010v2.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

11. Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207-216.

12. Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, et al; Alzheimer’s Association; Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging; Amyloid Imaging Taskforce. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: a report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:e1-e16.

13. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National coverage determination (NCD) for FDG PET for dementia and neurodegenerative diseases (220.6.13). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/ncd-details.aspx?NCDId=288&ncdver=3&bc=BAABAAAAAAAA&. Accessed March 21, 2015.

14. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Ruckson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270-179.

15. Mitchell AJ, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia—meta-analysis of 41 robust inception studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:252-265.

16. Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, et al. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic- vs community-based cohorts. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1151-1157.

17. Bensadon BA, Odenheimer GL. Current management decisions in mild cognitive impairment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29:847-871.

18. Ngo-Metzger Q, August KJ, Srinivasan M, et al. End-of-life care: guidelines for patient-centered communication. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77: 167-174.

19. Sayegh P, Knight BG. Cross-cultural differences in dementia: the Sociocultural Health Belief Model. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:517-530.

20. McDaniel SH, Campbell TL, Hepworth J, et al. Family-Oriented Primary Care. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2005.

21. Bensadon BA, Odenheimer GL. Current management decisions in mild cognitive impairment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013:29;847-871.

22. Russ TC, Morling JR. Cholinesterase inhibitors for mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD009132.

23. Sadowsky CH, Galvin JE. Guidelines for the management of cognitive and behavioral problems in dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25: 350-366.

24. Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005593.

25. Fillit HM, Doody RS, Binaso K, et al. Recommendations for best practices in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in managed care. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(suppl A):S9-S24;quiz S25-S28.

26. Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al; CATIE-AD Study Group. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525-1538.

27. FDA. Public health advisory: Deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm053171.htm. Updated August 16, 2013. Accessed March 21, 2015.

28. The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60: 616-631.

29. Brummel-Smith K. It’s time to require written informed consent when using antipsychotics in dementia. Br J Med Pract. 2008;1:4-6.

30. Huckans M, Hutson L, Twamley E, et al. Efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation therapies for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in older adults: working toward a theoretical model and evidence-based interventions. Neuropsychol Rev. 2013;23:63-80.

31. Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, et al. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD005562.

32. McLaren AN, Lamantia MA, Callahan CM. Systematic review of non-pharmacologic interventions to delay functional decline in community-dwelling patients with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17:655-666.

33. Bahar-Fuchs A, Clare L, Woods B. Cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD003260.

34. Logsdon RG, McCurry SM, Teri L. Evidence-based psychological treatments for disruptive behaviors in individuals with dementia. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:28-36.

35. Raetz J. A nondrug approach to dementia. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:548-557.

36. Gallagher-Thompson D, Coon DW. Evidence-based psychological treatments for distress in family caregivers of older adults. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:37-51.

37. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009:361:1529-1538.

38. Parsons C, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, et al. Withholding, discontinuing and withdrawing medications in dementia patients at the end of life: a neglected problem in the disadvantaged dying? Drugs Aging. 2010; 27:435-449.

39. The American Geriatrics Society. Feeding tubes in advanced dementia position statement. www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/feeding.tubes.advanced.dementia.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

40. Goodman C, Evans C, Wilcock J, et al. End of life care for community dwelling older people with dementia: an integrated review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:329-337.

41. Storey CP. A quick-reference guide to the hospice and palliative care training for physicians: UNIPAC self-study program. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Chicago; 2009.

42. Kaszniak AW, Kligman EW. Hospice care for patients with dementia. Elder Care. 2013. http://azalz.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Hospice-Care-for-Pts-with-Dementia.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

43. Daviglus ML, Bell CC, Berrettini W, et al. NIH state-of-the-science conference statement: Preventing Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2010;27:1-30.

44. Patterson C, Feightner JW, Garcia A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 1. Risk assessment and primary prevention of Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2008;178:548-556.

45. Carrillo MC, Brashear HR, Logovinsky V, et al. Can we prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Secondary “prevention” trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:123-131.e1.

46. Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, et al; Bapineuzumab 301 and 302 Clinical Trial Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:322-333.

47. Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, et al; Alheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Steering Committee; Solanezumab Study Group. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:311-321.

Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, affects more than 5 million Americans.1 Estimates suggest that by 2050, the prevalence could triple, reaching 13 to 16 million.1 To effectively care for patients with AD and their families, primary care providers need to be familiar with the latest evidence on all facets of care, from initial detection to patient management and end-of-life care.

This evidence-based review will help you toward that end by answering common questions regarding Alzheimer care, including whether routine screening is advisable, what tests should be ordered, which interventions (including nonpharmacologic options) are worth considering, and how best to counsel patients and families about end-of-life care.

ROUTINE SCREENING? STILL SUBJECT TO DEBATE

The key question regarding routine dementia screening in primary care is whether it improves outcomes. Advocates note that individuals with dementia may appear unimpaired during office visits and may not report symptoms due to lack of insight; they point out, too, that waiting for an event that makes cognitive impairment obvious (eg, driving mishap) is risky.2 Those who advocate routine screening also note that only about half of those who have dementia are ever diagnosed.3

Others, including the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), disagree. In its 2014 evidence review, the USPSTF indicated that there is “insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for cognitive impairment in older adults.”4

Mixed messages

The dearth of evidence is also reflected in the conflicting recommendations of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The ACA requires clinicians to assess cognitive function during Medicare patients’ annual wellness visits. CMS, however, instructs providers to screen for dementia only if observation or concerns raised by the patient or family suggest the possibility of impairment and does not recommend any particular test.5

Cost-effectiveness analyses also raise questions about the value of routine screening. Evidence suggests that screening 300 older patients will yield 39 positive results. But only about half of those will agree to a diagnostic evaluation, and no more than nine will ultimately be diagnosed with dementia. The estimated cost of identifying nine cases is nearly $40,000—all in the absence of a treatment to cure or stop the progression of the disorder.6

The bottom line: Evidence does not support routine dementia screening of older adults. When cognitive impairment is suspected, however, clinicians should conduct a diagnostic evaluation—and consider educating patients and families about the Alzheimer’s Association (AA)’s 10 Warning Signs of AD (see box, above).7 A longer version (www.alz.org/national/documents/checklist_10signs.pdf) outlines the cognitive changes that are characteristic of healthy aging and compares them to changes suggestive of early dementia.7

Next: How to proceed when you suspect AD >>

HOW TO PROCEED WHEN YOU SUSPECT AD

Step 1: Screening instrument. The first step in the diagnostic evaluation of a patient with suspected AD is to determine if, in fact, cognitive impairment is present. This can be assessed with in-office screening instruments, such as the Mini-Cog (http://bit.ly/1FwQAkG) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; http://bit.ly/18Djin5), among others.8

Step 2: Clinical evaluation. If observation and test results suggest cognitive impairment, the next step is to determine whether clinical findings are consistent with the diagnostic criteria for AD (see Table 1)9 developed by workgroups from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the AA in 2011. A work-up is necessary to identify conditions that can mimic dementia (eg, depression) and behaviors that suggest another type of dementia, such as frontotemporal or Lewy body dementia.10 Lab testing should be included to rule out potentially reversible causes of cognitive dysfunction (eg, hypothyroidism, vitamin D deficiency).

Step 3: Neuropsychologic evaluation. The NIA/AA recommends neuropsychologic testing when the brief cognitive tests, history, and clinical work-up are not sufficient for a definitive diagnosis of dementia.9 This generally involves a referral to a neuropsychologist, who conducts a battery of standardized tests to evaluate attention, memory, language, visual-spatial abilities, and executive functions, among others. Neuropsychologic testing can confirm the presence of cognitive impairment and aid in the differential diagnosis by comparing the patient’s performance in these domains with characteristic features of different dementia syndromes.

Step 4: Brain imaging with either CT or MRI can be included in the work-up for patients with suspected AD to rule out abnormalities (eg, metastatic cancer, hydrocephalus, or occult chronic subdural hematoma) that could be causing cognitive impairment.9,10 Clinical features that generally warrant brain imaging include onset of cognitive impairment before age 60; unexplained focal neurologic signs or symptoms; abrupt onset or rapid decline; and/or predisposing conditions (eg, cancer or anticoagulant treatment).10

The role of biomarkers and advanced brain imaging

Biomarkers that might provide confirmation of AD in patients who exhibit early symptoms of dementia have been studied extensively.11 The NIA/AA identified two categories of AD biomarkers

• Tests for β-amyloid deposition in the brain, including spinal fluid assays for β-amyloid (Aβ42) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans after IV injection of florbetapir or flutemetamol, which bind to amyloid in the brain; and

• Tests for neuronal degeneration, which would include spinal fluid assays for tau protein and PET scans after injection of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), which shows decreased uptake in patients with AD.9

Research reveals the promise of these biomarkers as diagnostic tools, particularly in patients with an atypical presentation of dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) that may be associated with early AD.12 (More on MCI in a moment.) However, the NIA/AA concluded that additional research is needed to validate these tests for routine diagnostic purposes. Medicare covers PET scans with FDG only for the differential diagnosis of AD versus frontotemporal dementia.13

Continue for mild cognitive impairment >>

MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: HOW LIKELY THAT IT WILL PROGRESS?

Along with diagnostic criteria for AD, the NIA/AA developed criteria for a symptomatic predementia phase of AD—often referred to as MCI.14 According to the workgroup, MCI is diagnosed when

1. The patient, an informant, or a clinician is concerned about the individual’s cognitive decline from previous levels of functioning

2. There is evidence of cognitive impairment, ideally through psychometric testing, revealing performance below expectation based on the patient’s age and education

3. The patient is able to maintain independent functioning in daily life, despite mild problems or the need for minimal assistance

4. There is no significant impairment in social or occupational functioning.14

Progression: Less likely than you might think

Patients with MCI are at risk for progression to overt dementia, with an overall annual conversion rate from MCI to dementia estimated at 10% to 15%.15,16 This estimate must be interpreted with caution, however, because most studies were conducted prior to the 2011 guidelines, when different diagnostic criteria were used. Observers have noted, too, that the numbers largely reflect data collected in specialty clinics and that community-based studies reveal substantially lower conversion rates (3% to 6% per year).16 In addition, evidence suggests that many patients with MCI demonstrate long-term stability or even reversal of deficits.17

While there is some consideration of the use of biomarkers and amyloid imaging tests to help determine which patients with MCI will progress to AD, practice guidelines do not currently recommend such testing and it is not covered by Medicare.

WHEN EVIDENCE INDICATES AN AD DIAGNOSIS

When faced with the need to communicate an AD diagnosis, follow the general recommendations for delivering any bad news or discouraging prognosis.

Prioritize and limit the information you provide, determining not only what the patient and family want to hear but also how much they are able to comprehend.

Confirm that the patient and family understand the information you’ve provided.

Offer emotional support and recommend additional resources (see Table 2).18

Given the progressive cognitive decline that characterizes AD, it is important to address the primary caregiver’s understanding of, and ability to cope with, the disease. It is also important to explore beliefs and attitudes regarding AD. Keep in mind that cultural groups tend to differ in their beliefs about the nature, cause, and appropriate management of AD, as well as the role of spirituality, help-seeking, and stigma.19,20

The progressive and ultimately fatal nature of AD also makes planning for the future a priority. Ideally, patients should be engaged in discussions regarding end-of-life care as early as possible, while they are still able to make informed decisions and express their preferences. Discussing end-of-life care can be overwhelming for newly diagnosed patients and their families, however, so it is important that you address issues—medical, financial, and legal planning, for example—that families should be considering.

Next: Medication for cognitive and behaviorial function >>

Drugs address cognitive and behavioral function

No currently available treatments can cure or significantly alter the progression of AD, but two classes of medications are used in an attempt to improve cognitive function. One is cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs), which potentiate acetylcholine synaptic transmission. The other is N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor blockers. Other classes of drugs are sometimes used to treat behavioral symptoms, such as agitation, aggression, mood disorders, and psychosis (eg, delusions, hallucinations).

Cognitive function. Results from studies of pharmacologic management of MCI vary widely, but recent reviews have found no convincing evidence that either ChEIs or NMDA receptor blockers have an effect on progression from MCI to dementia.21,22 Neither class is FDA-approved for treatment of MCI.

In patients with dementia, the effects of ChEIs and NMDA receptor blockers on cognition are statistically significant but modest and often of questionable clinical relevance.23 Nonetheless, among ChEIs, donepezil is approved by the FDA for mild, moderate, and severe dementia, and galantamine and rivastigmine are approved for mild and moderate dementia. There is no evidence that one ChEI is more effective than another,24 and the choice is often guided by cost, adverse effects, and health plan formularies. Memantine, the only FDA-approved NMDA receptor blocker, is approved for moderate to severe dementia and can be used alone or in combination with a ChEI.

If these drugs are used in an attempt to improve cognition in AD, guidelines recommend the following approach for initial therapy: Prescribe a ChEI for the mild stage, a ChEI plus memantine for the moderate stage, and memantine (with or without a ChEI) for the severe stage.25 The recommendations also include monitoring every six months.

There is no consensus about when to discontinue medication. Various published recommendations call for continuing treatment until the patient has “lost all cognitive and functional abilities;”22 until the patient’s MMSE score falls below 10 and there is no indication that the drug is having a “worthwhile effect;”21 or until he or she has reached stage 7 on the Reisberg Functional Assessment Staging scale, indicating nonambulatory status with speech limited to one to five words a day.10

Behavioral function. A variety of drugs are used to treat behavioral symptoms in AD. While not FDA-approved for this use, the most widely prescribed agents are second-generation antipsychotics (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone). The main effect of these drugs is often nothing more than sedation, and one large multisite clinical trial concluded that the adverse effects offset the benefits for patients with AD.26 Indeed, the FDA has issued an advisory on the use of second-generation antipsychotics in AD patients, stating that they are associated with increased mortality risk.27 The recently updated Beers Criteria strongly recommend avoiding these drugs for treatment of behavioral disturbances in AD unless nonpharmacologic options have failed and the patient is a threat to self or others.28

Because of the black-box warning that antipsychotics increase the risk for death, some clinicians have advocated obtaining informed consent prior to prescribing such medications.29 At the very least, when family or guardians are involved, a conversation about risks versus benefits should take place and be documented in the medical record.

Other drug classes are also sometimes used in an attempt to improve behavioral function, including antiseizure medications (valproic acid, carbamazepine), antidepressants (trazodone and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), and anxiolytics (benzodiazepines and buspirone). Other than their sedating effects, there is no strong evidence that these drugs are effective for treating dementia-related behavioral disorders. If used, caution is required due to potential adverse effects.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT IS "PROMISING"

A recent systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions for MCI evaluated exercise, training in compensatory strategies, and engagement in cognitively stimulating activities and found “promising but inconclusive” results. The researchers found that studies show mostly positive effects on cognition but have significant methodologic limitations.30 Importantly, there is no evidence of delayed or reduced conversion to dementia.

For patients who already have mild-to-moderate dementia, cognitive stimulation seems to help in the short term.31 There is also some evidence that exercise and occupational therapy may slow functional decline,32 but the effects are small to modest and their actual clinical significance (eg, the ability to delay institutionalization) is unclear. There is promising but preliminary evidence that cognitive rehabilitation (helping patients devise strategies to complete daily activities) may improve functioning in everyday life.33

While behavioral symptoms are often due to the dementia itself, it is important to identify and treat medical and environmental causes that may be contributing, such as infection, pain, and loud or unsafe environments. As noted before, nonpharmacologic treatments are generally preferred for behavioral problems and should be considered prior to drug therapy. Approaches that identify and modify both the antecedents and consequences of problem behaviors and increase pleasant events have empiric support for the management of behavioral symptoms.34 Interventions including massage therapy, aromatherapy, exercise, and music therapy may also be effective in the short term for agitated behavior.35

Caregivers should be encouraged to receive training in these strategies through organizations such as AA. Caregiver education and support can reduce caregivers’ distress and increase their self-efficacy and coping skills.36

Continue: Is it time for hospice? >>

END-OF-LIFE CARE MUST BE ADDRESSED

Perhaps the most important aspect of end-of-life care in AD is assuring that families (or health care proxies) understand that AD is a fatal illness, with most patients dying within four to eight years of diagnosis.1 Evidence indicates that patients whose proxies have a clear recognition of this are less likely to experience “burdensome” interventions such as parenteral therapy, emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and tube feedings in their last three months of life.37

Overall, decisions regarding discontinuing medical treatments in advanced AD should be made by balancing the likelihood of benefit with the potential for adverse effects.38 For example, the American Geriatrics Society recently recommended against feeding tubes because they often result in discomfort due to agitation, use of restraints, and worsening pressure ulcers.39

Unfortunately, only a minority of families receives straightforward information on the course and prognosis of AD, including the fact that patients eventually stop eating and that the natural cause of death is often an acute infection. Studies also show that patients with dementia are at risk for inadequate treatment of pain.40 Assuring adequate pain control is an essential component of end-of-life care.

Hospice. End-of-life care can often be improved with hospice care. This service is underused by patients with dementia, even though hospice care is available at no cost through Medicare. Hospice eligibility criteria for patients with AD are shown in Table 3.41,42

Next page: Prevention >>

FINALLY, A WORD ABOUT PREVENTION

Numerous risk factors have been associated with an increased risk for AD (see Table 4).2,3 Some, like age and genetics, are nonmodifiable, while others—particularly cardiovascular risk factors—can be modified.1 There are also factors associated with decreased risks—most notably, physical exercise and participation in cognitively stimulating activities.3 Identification of these factors has led to the hope that addressing them can prevent AD.

But association does not equal causation. In 2010, a report from the National Institutes of Health concluded that, although there are modifiable factors associated with AD, there is insufficient evidence that addressing any of them will actually prevent AD.43 In fact, there is good evidence that some of these factors (eg, statin therapy) are not effective in reducing the incidence of dementia and that others (eg, vitamin E and estrogen therapy) are potentially harmful.44

The absence of empirically supported preventive interventions does not mean, however, that we should disregard these risks and protective factors. Encouraging social engagement, for example, may improve both emotional health and quality of life. Addressing cardiovascular risk factors can reduce the rate of coronary and cerebrovascular disease, potentially including vascular dementia, even if it does not reduce the rate of AD.

Studies are evaluating the use of monoclonal antibodies with anti-amyloid properties for prevention of AD in individuals who have APOE ε4 genotypes or high amyloid loads on neuroimaging.45 It will be several years before results are available, however, and the outcome of these studies is uncertain, as the use of anti-amyloid agents for treating established dementia has not been effective.46,47

REFERENCES

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2013.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

2. Román GC, Nash DT, Fillit H. Translating current knowledge into dementia prevention. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:295-299.

3. Jak AJ. The impact of physical and mental activity on cognitive aging. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;10:273-291.

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening. Accessed March 21, 2015.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Guide to Medicare Preventive Services. 4th ed. 2011. www.curemd.com/fqhc/The%20Guide%20to%20Medicare%20Preventative%20Services%20for%20Physicans,%20Providers%20and%20Suppliers.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

6. Boustani M. Dementia screening in primary care: not too fast! J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1205-1207.

7. Alzheimer’s Association. Know the 10 signs: early detection matters. www.alz.org/national/documents/checklist_10signs.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

8. Cordell CB, Borson S, Boustani M, et al; Medicare Detection of Cognitive Impairment Workgroup. Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit in a primary care setting. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:141-150.

9. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263-269.

10. The American Geriatrics Society. A guide to dementia diagnosis and treatment. http://dementia.americangeriatrics.org/documents/AGS_PC_Dementia_Sheet_2010v2.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

11. Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207-216.

12. Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, et al; Alzheimer’s Association; Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging; Amyloid Imaging Taskforce. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: a report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:e1-e16.

13. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National coverage determination (NCD) for FDG PET for dementia and neurodegenerative diseases (220.6.13). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/ncd-details.aspx?NCDId=288&ncdver=3&bc=BAABAAAAAAAA&. Accessed March 21, 2015.

14. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Ruckson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270-179.

15. Mitchell AJ, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia—meta-analysis of 41 robust inception studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:252-265.

16. Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, et al. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic- vs community-based cohorts. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1151-1157.

17. Bensadon BA, Odenheimer GL. Current management decisions in mild cognitive impairment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29:847-871.

18. Ngo-Metzger Q, August KJ, Srinivasan M, et al. End-of-life care: guidelines for patient-centered communication. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77: 167-174.

19. Sayegh P, Knight BG. Cross-cultural differences in dementia: the Sociocultural Health Belief Model. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:517-530.

20. McDaniel SH, Campbell TL, Hepworth J, et al. Family-Oriented Primary Care. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2005.

21. Bensadon BA, Odenheimer GL. Current management decisions in mild cognitive impairment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013:29;847-871.

22. Russ TC, Morling JR. Cholinesterase inhibitors for mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD009132.

23. Sadowsky CH, Galvin JE. Guidelines for the management of cognitive and behavioral problems in dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25: 350-366.

24. Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005593.

25. Fillit HM, Doody RS, Binaso K, et al. Recommendations for best practices in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in managed care. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(suppl A):S9-S24;quiz S25-S28.

26. Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al; CATIE-AD Study Group. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525-1538.

27. FDA. Public health advisory: Deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm053171.htm. Updated August 16, 2013. Accessed March 21, 2015.

28. The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60: 616-631.

29. Brummel-Smith K. It’s time to require written informed consent when using antipsychotics in dementia. Br J Med Pract. 2008;1:4-6.

30. Huckans M, Hutson L, Twamley E, et al. Efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation therapies for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in older adults: working toward a theoretical model and evidence-based interventions. Neuropsychol Rev. 2013;23:63-80.

31. Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, et al. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD005562.

32. McLaren AN, Lamantia MA, Callahan CM. Systematic review of non-pharmacologic interventions to delay functional decline in community-dwelling patients with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17:655-666.

33. Bahar-Fuchs A, Clare L, Woods B. Cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD003260.

34. Logsdon RG, McCurry SM, Teri L. Evidence-based psychological treatments for disruptive behaviors in individuals with dementia. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:28-36.

35. Raetz J. A nondrug approach to dementia. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:548-557.

36. Gallagher-Thompson D, Coon DW. Evidence-based psychological treatments for distress in family caregivers of older adults. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:37-51.

37. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009:361:1529-1538.

38. Parsons C, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, et al. Withholding, discontinuing and withdrawing medications in dementia patients at the end of life: a neglected problem in the disadvantaged dying? Drugs Aging. 2010; 27:435-449.

39. The American Geriatrics Society. Feeding tubes in advanced dementia position statement. www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/feeding.tubes.advanced.dementia.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

40. Goodman C, Evans C, Wilcock J, et al. End of life care for community dwelling older people with dementia: an integrated review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:329-337.

41. Storey CP. A quick-reference guide to the hospice and palliative care training for physicians: UNIPAC self-study program. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Chicago; 2009.

42. Kaszniak AW, Kligman EW. Hospice care for patients with dementia. Elder Care. 2013. http://azalz.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Hospice-Care-for-Pts-with-Dementia.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

43. Daviglus ML, Bell CC, Berrettini W, et al. NIH state-of-the-science conference statement: Preventing Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2010;27:1-30.

44. Patterson C, Feightner JW, Garcia A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 1. Risk assessment and primary prevention of Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2008;178:548-556.

45. Carrillo MC, Brashear HR, Logovinsky V, et al. Can we prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Secondary “prevention” trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:123-131.e1.

46. Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, et al; Bapineuzumab 301 and 302 Clinical Trial Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:322-333.

47. Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, et al; Alheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Steering Committee; Solanezumab Study Group. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:311-321.

Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, affects more than 5 million Americans.1 Estimates suggest that by 2050, the prevalence could triple, reaching 13 to 16 million.1 To effectively care for patients with AD and their families, primary care providers need to be familiar with the latest evidence on all facets of care, from initial detection to patient management and end-of-life care.

This evidence-based review will help you toward that end by answering common questions regarding Alzheimer care, including whether routine screening is advisable, what tests should be ordered, which interventions (including nonpharmacologic options) are worth considering, and how best to counsel patients and families about end-of-life care.

ROUTINE SCREENING? STILL SUBJECT TO DEBATE

The key question regarding routine dementia screening in primary care is whether it improves outcomes. Advocates note that individuals with dementia may appear unimpaired during office visits and may not report symptoms due to lack of insight; they point out, too, that waiting for an event that makes cognitive impairment obvious (eg, driving mishap) is risky.2 Those who advocate routine screening also note that only about half of those who have dementia are ever diagnosed.3

Others, including the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), disagree. In its 2014 evidence review, the USPSTF indicated that there is “insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for cognitive impairment in older adults.”4

Mixed messages

The dearth of evidence is also reflected in the conflicting recommendations of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The ACA requires clinicians to assess cognitive function during Medicare patients’ annual wellness visits. CMS, however, instructs providers to screen for dementia only if observation or concerns raised by the patient or family suggest the possibility of impairment and does not recommend any particular test.5

Cost-effectiveness analyses also raise questions about the value of routine screening. Evidence suggests that screening 300 older patients will yield 39 positive results. But only about half of those will agree to a diagnostic evaluation, and no more than nine will ultimately be diagnosed with dementia. The estimated cost of identifying nine cases is nearly $40,000—all in the absence of a treatment to cure or stop the progression of the disorder.6

The bottom line: Evidence does not support routine dementia screening of older adults. When cognitive impairment is suspected, however, clinicians should conduct a diagnostic evaluation—and consider educating patients and families about the Alzheimer’s Association (AA)’s 10 Warning Signs of AD (see box, above).7 A longer version (www.alz.org/national/documents/checklist_10signs.pdf) outlines the cognitive changes that are characteristic of healthy aging and compares them to changes suggestive of early dementia.7

Next: How to proceed when you suspect AD >>

HOW TO PROCEED WHEN YOU SUSPECT AD

Step 1: Screening instrument. The first step in the diagnostic evaluation of a patient with suspected AD is to determine if, in fact, cognitive impairment is present. This can be assessed with in-office screening instruments, such as the Mini-Cog (http://bit.ly/1FwQAkG) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; http://bit.ly/18Djin5), among others.8

Step 2: Clinical evaluation. If observation and test results suggest cognitive impairment, the next step is to determine whether clinical findings are consistent with the diagnostic criteria for AD (see Table 1)9 developed by workgroups from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the AA in 2011. A work-up is necessary to identify conditions that can mimic dementia (eg, depression) and behaviors that suggest another type of dementia, such as frontotemporal or Lewy body dementia.10 Lab testing should be included to rule out potentially reversible causes of cognitive dysfunction (eg, hypothyroidism, vitamin D deficiency).

Step 3: Neuropsychologic evaluation. The NIA/AA recommends neuropsychologic testing when the brief cognitive tests, history, and clinical work-up are not sufficient for a definitive diagnosis of dementia.9 This generally involves a referral to a neuropsychologist, who conducts a battery of standardized tests to evaluate attention, memory, language, visual-spatial abilities, and executive functions, among others. Neuropsychologic testing can confirm the presence of cognitive impairment and aid in the differential diagnosis by comparing the patient’s performance in these domains with characteristic features of different dementia syndromes.

Step 4: Brain imaging with either CT or MRI can be included in the work-up for patients with suspected AD to rule out abnormalities (eg, metastatic cancer, hydrocephalus, or occult chronic subdural hematoma) that could be causing cognitive impairment.9,10 Clinical features that generally warrant brain imaging include onset of cognitive impairment before age 60; unexplained focal neurologic signs or symptoms; abrupt onset or rapid decline; and/or predisposing conditions (eg, cancer or anticoagulant treatment).10

The role of biomarkers and advanced brain imaging

Biomarkers that might provide confirmation of AD in patients who exhibit early symptoms of dementia have been studied extensively.11 The NIA/AA identified two categories of AD biomarkers

• Tests for β-amyloid deposition in the brain, including spinal fluid assays for β-amyloid (Aβ42) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans after IV injection of florbetapir or flutemetamol, which bind to amyloid in the brain; and

• Tests for neuronal degeneration, which would include spinal fluid assays for tau protein and PET scans after injection of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), which shows decreased uptake in patients with AD.9

Research reveals the promise of these biomarkers as diagnostic tools, particularly in patients with an atypical presentation of dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) that may be associated with early AD.12 (More on MCI in a moment.) However, the NIA/AA concluded that additional research is needed to validate these tests for routine diagnostic purposes. Medicare covers PET scans with FDG only for the differential diagnosis of AD versus frontotemporal dementia.13

Continue for mild cognitive impairment >>

MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: HOW LIKELY THAT IT WILL PROGRESS?

Along with diagnostic criteria for AD, the NIA/AA developed criteria for a symptomatic predementia phase of AD—often referred to as MCI.14 According to the workgroup, MCI is diagnosed when

1. The patient, an informant, or a clinician is concerned about the individual’s cognitive decline from previous levels of functioning

2. There is evidence of cognitive impairment, ideally through psychometric testing, revealing performance below expectation based on the patient’s age and education

3. The patient is able to maintain independent functioning in daily life, despite mild problems or the need for minimal assistance

4. There is no significant impairment in social or occupational functioning.14

Progression: Less likely than you might think

Patients with MCI are at risk for progression to overt dementia, with an overall annual conversion rate from MCI to dementia estimated at 10% to 15%.15,16 This estimate must be interpreted with caution, however, because most studies were conducted prior to the 2011 guidelines, when different diagnostic criteria were used. Observers have noted, too, that the numbers largely reflect data collected in specialty clinics and that community-based studies reveal substantially lower conversion rates (3% to 6% per year).16 In addition, evidence suggests that many patients with MCI demonstrate long-term stability or even reversal of deficits.17

While there is some consideration of the use of biomarkers and amyloid imaging tests to help determine which patients with MCI will progress to AD, practice guidelines do not currently recommend such testing and it is not covered by Medicare.

WHEN EVIDENCE INDICATES AN AD DIAGNOSIS

When faced with the need to communicate an AD diagnosis, follow the general recommendations for delivering any bad news or discouraging prognosis.

Prioritize and limit the information you provide, determining not only what the patient and family want to hear but also how much they are able to comprehend.

Confirm that the patient and family understand the information you’ve provided.

Offer emotional support and recommend additional resources (see Table 2).18

Given the progressive cognitive decline that characterizes AD, it is important to address the primary caregiver’s understanding of, and ability to cope with, the disease. It is also important to explore beliefs and attitudes regarding AD. Keep in mind that cultural groups tend to differ in their beliefs about the nature, cause, and appropriate management of AD, as well as the role of spirituality, help-seeking, and stigma.19,20

The progressive and ultimately fatal nature of AD also makes planning for the future a priority. Ideally, patients should be engaged in discussions regarding end-of-life care as early as possible, while they are still able to make informed decisions and express their preferences. Discussing end-of-life care can be overwhelming for newly diagnosed patients and their families, however, so it is important that you address issues—medical, financial, and legal planning, for example—that families should be considering.

Next: Medication for cognitive and behaviorial function >>

Drugs address cognitive and behavioral function

No currently available treatments can cure or significantly alter the progression of AD, but two classes of medications are used in an attempt to improve cognitive function. One is cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs), which potentiate acetylcholine synaptic transmission. The other is N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor blockers. Other classes of drugs are sometimes used to treat behavioral symptoms, such as agitation, aggression, mood disorders, and psychosis (eg, delusions, hallucinations).

Cognitive function. Results from studies of pharmacologic management of MCI vary widely, but recent reviews have found no convincing evidence that either ChEIs or NMDA receptor blockers have an effect on progression from MCI to dementia.21,22 Neither class is FDA-approved for treatment of MCI.

In patients with dementia, the effects of ChEIs and NMDA receptor blockers on cognition are statistically significant but modest and often of questionable clinical relevance.23 Nonetheless, among ChEIs, donepezil is approved by the FDA for mild, moderate, and severe dementia, and galantamine and rivastigmine are approved for mild and moderate dementia. There is no evidence that one ChEI is more effective than another,24 and the choice is often guided by cost, adverse effects, and health plan formularies. Memantine, the only FDA-approved NMDA receptor blocker, is approved for moderate to severe dementia and can be used alone or in combination with a ChEI.

If these drugs are used in an attempt to improve cognition in AD, guidelines recommend the following approach for initial therapy: Prescribe a ChEI for the mild stage, a ChEI plus memantine for the moderate stage, and memantine (with or without a ChEI) for the severe stage.25 The recommendations also include monitoring every six months.

There is no consensus about when to discontinue medication. Various published recommendations call for continuing treatment until the patient has “lost all cognitive and functional abilities;”22 until the patient’s MMSE score falls below 10 and there is no indication that the drug is having a “worthwhile effect;”21 or until he or she has reached stage 7 on the Reisberg Functional Assessment Staging scale, indicating nonambulatory status with speech limited to one to five words a day.10

Behavioral function. A variety of drugs are used to treat behavioral symptoms in AD. While not FDA-approved for this use, the most widely prescribed agents are second-generation antipsychotics (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone). The main effect of these drugs is often nothing more than sedation, and one large multisite clinical trial concluded that the adverse effects offset the benefits for patients with AD.26 Indeed, the FDA has issued an advisory on the use of second-generation antipsychotics in AD patients, stating that they are associated with increased mortality risk.27 The recently updated Beers Criteria strongly recommend avoiding these drugs for treatment of behavioral disturbances in AD unless nonpharmacologic options have failed and the patient is a threat to self or others.28

Because of the black-box warning that antipsychotics increase the risk for death, some clinicians have advocated obtaining informed consent prior to prescribing such medications.29 At the very least, when family or guardians are involved, a conversation about risks versus benefits should take place and be documented in the medical record.

Other drug classes are also sometimes used in an attempt to improve behavioral function, including antiseizure medications (valproic acid, carbamazepine), antidepressants (trazodone and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), and anxiolytics (benzodiazepines and buspirone). Other than their sedating effects, there is no strong evidence that these drugs are effective for treating dementia-related behavioral disorders. If used, caution is required due to potential adverse effects.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT IS "PROMISING"

A recent systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions for MCI evaluated exercise, training in compensatory strategies, and engagement in cognitively stimulating activities and found “promising but inconclusive” results. The researchers found that studies show mostly positive effects on cognition but have significant methodologic limitations.30 Importantly, there is no evidence of delayed or reduced conversion to dementia.

For patients who already have mild-to-moderate dementia, cognitive stimulation seems to help in the short term.31 There is also some evidence that exercise and occupational therapy may slow functional decline,32 but the effects are small to modest and their actual clinical significance (eg, the ability to delay institutionalization) is unclear. There is promising but preliminary evidence that cognitive rehabilitation (helping patients devise strategies to complete daily activities) may improve functioning in everyday life.33

While behavioral symptoms are often due to the dementia itself, it is important to identify and treat medical and environmental causes that may be contributing, such as infection, pain, and loud or unsafe environments. As noted before, nonpharmacologic treatments are generally preferred for behavioral problems and should be considered prior to drug therapy. Approaches that identify and modify both the antecedents and consequences of problem behaviors and increase pleasant events have empiric support for the management of behavioral symptoms.34 Interventions including massage therapy, aromatherapy, exercise, and music therapy may also be effective in the short term for agitated behavior.35

Caregivers should be encouraged to receive training in these strategies through organizations such as AA. Caregiver education and support can reduce caregivers’ distress and increase their self-efficacy and coping skills.36

Continue: Is it time for hospice? >>

END-OF-LIFE CARE MUST BE ADDRESSED

Perhaps the most important aspect of end-of-life care in AD is assuring that families (or health care proxies) understand that AD is a fatal illness, with most patients dying within four to eight years of diagnosis.1 Evidence indicates that patients whose proxies have a clear recognition of this are less likely to experience “burdensome” interventions such as parenteral therapy, emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and tube feedings in their last three months of life.37

Overall, decisions regarding discontinuing medical treatments in advanced AD should be made by balancing the likelihood of benefit with the potential for adverse effects.38 For example, the American Geriatrics Society recently recommended against feeding tubes because they often result in discomfort due to agitation, use of restraints, and worsening pressure ulcers.39

Unfortunately, only a minority of families receives straightforward information on the course and prognosis of AD, including the fact that patients eventually stop eating and that the natural cause of death is often an acute infection. Studies also show that patients with dementia are at risk for inadequate treatment of pain.40 Assuring adequate pain control is an essential component of end-of-life care.

Hospice. End-of-life care can often be improved with hospice care. This service is underused by patients with dementia, even though hospice care is available at no cost through Medicare. Hospice eligibility criteria for patients with AD are shown in Table 3.41,42

Next page: Prevention >>

FINALLY, A WORD ABOUT PREVENTION

Numerous risk factors have been associated with an increased risk for AD (see Table 4).2,3 Some, like age and genetics, are nonmodifiable, while others—particularly cardiovascular risk factors—can be modified.1 There are also factors associated with decreased risks—most notably, physical exercise and participation in cognitively stimulating activities.3 Identification of these factors has led to the hope that addressing them can prevent AD.

But association does not equal causation. In 2010, a report from the National Institutes of Health concluded that, although there are modifiable factors associated with AD, there is insufficient evidence that addressing any of them will actually prevent AD.43 In fact, there is good evidence that some of these factors (eg, statin therapy) are not effective in reducing the incidence of dementia and that others (eg, vitamin E and estrogen therapy) are potentially harmful.44

The absence of empirically supported preventive interventions does not mean, however, that we should disregard these risks and protective factors. Encouraging social engagement, for example, may improve both emotional health and quality of life. Addressing cardiovascular risk factors can reduce the rate of coronary and cerebrovascular disease, potentially including vascular dementia, even if it does not reduce the rate of AD.

Studies are evaluating the use of monoclonal antibodies with anti-amyloid properties for prevention of AD in individuals who have APOE ε4 genotypes or high amyloid loads on neuroimaging.45 It will be several years before results are available, however, and the outcome of these studies is uncertain, as the use of anti-amyloid agents for treating established dementia has not been effective.46,47

REFERENCES

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2013.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

2. Román GC, Nash DT, Fillit H. Translating current knowledge into dementia prevention. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:295-299.

3. Jak AJ. The impact of physical and mental activity on cognitive aging. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;10:273-291.

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening. Accessed March 21, 2015.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Guide to Medicare Preventive Services. 4th ed. 2011. www.curemd.com/fqhc/The%20Guide%20to%20Medicare%20Preventative%20Services%20for%20Physicans,%20Providers%20and%20Suppliers.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

6. Boustani M. Dementia screening in primary care: not too fast! J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1205-1207.

7. Alzheimer’s Association. Know the 10 signs: early detection matters. www.alz.org/national/documents/checklist_10signs.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

8. Cordell CB, Borson S, Boustani M, et al; Medicare Detection of Cognitive Impairment Workgroup. Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit in a primary care setting. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:141-150.

9. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263-269.

10. The American Geriatrics Society. A guide to dementia diagnosis and treatment. http://dementia.americangeriatrics.org/documents/AGS_PC_Dementia_Sheet_2010v2.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

11. Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207-216.

12. Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, et al; Alzheimer’s Association; Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging; Amyloid Imaging Taskforce. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: a report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:e1-e16.

13. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National coverage determination (NCD) for FDG PET for dementia and neurodegenerative diseases (220.6.13). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/ncd-details.aspx?NCDId=288&ncdver=3&bc=BAABAAAAAAAA&. Accessed March 21, 2015.

14. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Ruckson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270-179.

15. Mitchell AJ, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia—meta-analysis of 41 robust inception studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:252-265.

16. Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, et al. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic- vs community-based cohorts. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1151-1157.

17. Bensadon BA, Odenheimer GL. Current management decisions in mild cognitive impairment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29:847-871.

18. Ngo-Metzger Q, August KJ, Srinivasan M, et al. End-of-life care: guidelines for patient-centered communication. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77: 167-174.

19. Sayegh P, Knight BG. Cross-cultural differences in dementia: the Sociocultural Health Belief Model. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:517-530.

20. McDaniel SH, Campbell TL, Hepworth J, et al. Family-Oriented Primary Care. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2005.