User login

Should we stop the oral selective estrogen receptor modulator raloxifene prior to surgery?

Should mesalamine be stopped prior to noncardiac surgery to avoid bleeding complications?

Pin the Pinworm

An 84‐year‐old female patient with hypertension, osteoarthritis, hypothyroidism, and remote breast cancer was admitted with complaints of generalized abdominal pain of 2 months' duration. Pain was described as noncolicky in nature and was associated with diarrhea. She reported 78 daily episodes of watery, non‐foul‐smelling diarrhea. She denied any nausea, vomiting, fever, joint pains, oral ulcers, eye redness, stool incontinence, melena, hematochezia, or weight loss. There was no history of recent travel, antibiotic use, or exposure to sick contacts. She had no risk factors for HIV infection or other sexually transmitted infections. Her social history was significant for dining out on a regular basis and living in an assisted living facility. However, she denied any relationship between her abdominal symptoms and any particular food intake or with bowel movements. She denied any anal pruritis but reported seeing white squiggly things on tissue paper after bowel movements. She denied use of over‐the‐counter laxatives or herbal supplements. None of her prescription medications had diarrhea as a major side effect. Her social history was unremarkable for smoking, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. There were no prior abdominal surgeries. The patient's physical exam showed normal vitals on presentation and was unremarkable except for vague, generalized abdominal tenderness with no involuntary guarding or rebound pain. Her initial laboratory evaluation showed normal complete blood counts with no eosinophilia and normal serum electrolytes and liver and thyroid panel. Acute‐phase reactants, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C‐reactive protein were not elevated. Stool evaluation was unremarkable for Clostridium difficile toxin, fat droplets, leukocytes, erythrocytes, ova, parasites, or any bacterial growth on cultures. Computed tomography scans of the abdomen and pelvis were nonrevealing. Her colonoscopic examination 1 year prior was significant only for diverticulosis.1, 2

The patient was treated with loperamide as an outpatient with no relief. She was then admitted to the hospital for further diagnostic workup. Hospital workup included a Scotch tape test, which showed adult pinworms. She was treated with a single dose of 400 mg of albendazole with complete resolution of her symptoms within 2 days. No further workup was done. Patient was discharged with advice to contact her primary care doctor for reevaluation if symptoms recurred. However, the patient remained symptom free 1 year after discharge.

DISCUSSION

Enterobius vermicularis is a parasite that infects 2040 million people annually in the United States and about 200 million people worldwide. Equal infection rates are seen in all races, socioeconomic classes, and cultures.1 It is more prevalent among those in crowded living conditions. Humans are the primary natural host for the parasite, although it has been documented in cockroaches and primates. Transmission occurs via the feco‐oral route or via airborne eggs that are dislodged from contaminated clothing or bed linen. Its life cycle begins with parasite eggs hatching in the duodenum, usually within 6 hours of ingestion. They mature into adults in as little as 2 weeks and have a life span of approximately 2 months. Enterobius vermicularis normally inhabits distal small bowel including the terminal ileum, cecum, and vermiform appendix, as well as the proximal ascending colon. After copulation, an adult female will migrate to the perineum, often at night, and lay an average of 10,00015,000 eggs. These eggs mature in about 6 hours and are then transmitted to a new host by the feco‐oral route. The worms live mainly in the intestinal lumen and do not invade tissue. Hence, pinworm infections, unlike many other parasitic infections, are rarely associated with serum eosinophilia or elevated serum IgE levels.

E. vermicularis is generally considered to be an innocuous parasite. Perianal pruritis, especially during the nighttime, is the most common symptom. Patients may develop secondary bacterial infection of the irritated anal skin. Rarely, E. vermicularis infection may result in a life‐threatening illness. A literature review showed pinworm infection to be an infrequent cause of eosinophilic enterocolitis, appendicitis, intestinal obstruction, intestinal perforation, hepatic infection, urinary tract infection, sialoadenitis, salpingitis, enterocolitis, eosinophilic ileocolitis, vulvovaginitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, conditions mimicking inflammatory bowel diseases, perianal abscesses, and perianal granulomas. In a retrospective review of 180 colonoscopies done on patients with rectal bleeding or suspected inflammatory bowel disease, E. vermicularis was identified macroscopically in 31 cases (17.2%). Data collected on 23 of these cases showed that symptoms were present for a mean of 17 months; the symptoms with the highest frequency were abdominal pain (73%), rectal bleeding (62%), chronic diarrhea (50%), and weight loss (42%). None of these patients experienced perianal pruritis or developed inflammatory bowel disease during the follow‐up period of up to 5 years, although 21 patients demonstrated histopathological evidence of nonspecific colitis.6

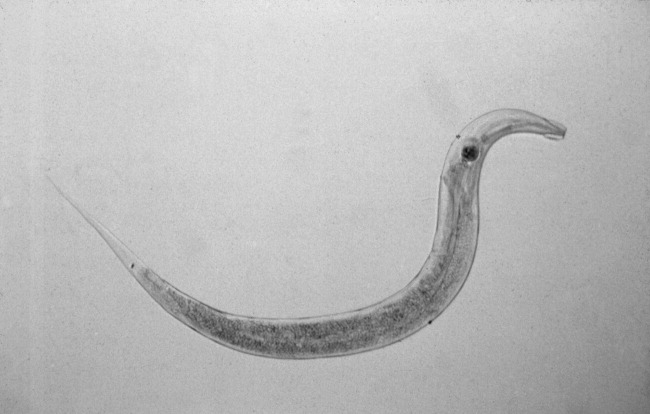

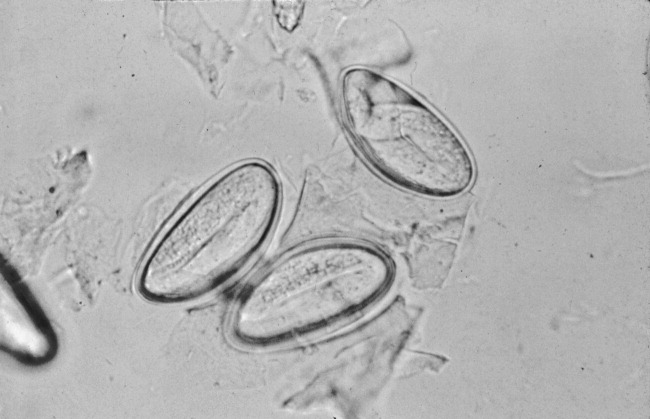

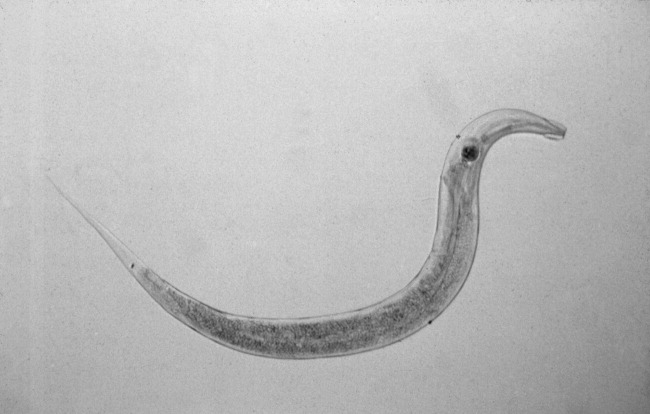

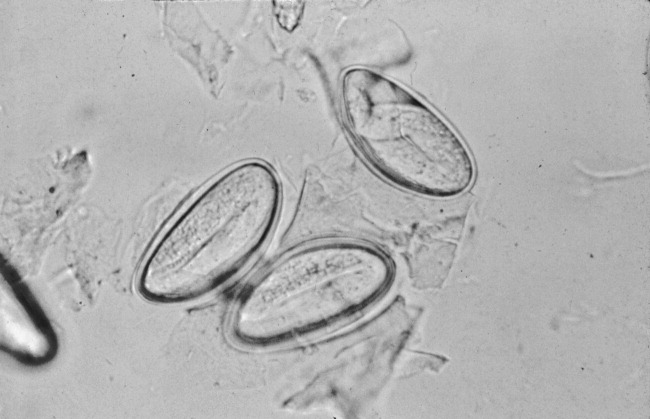

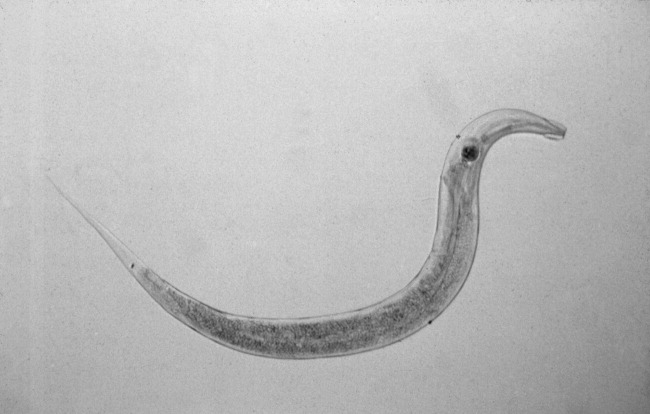

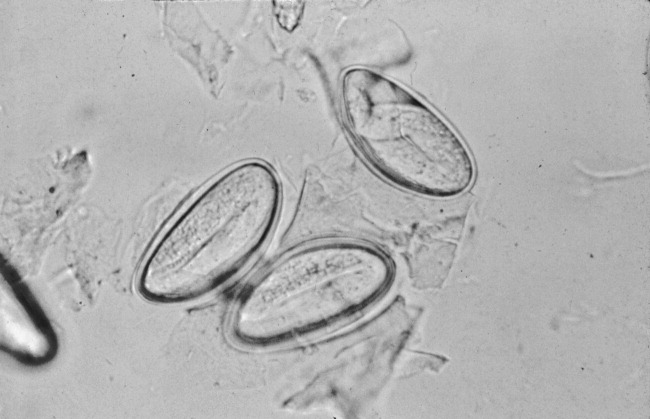

The gold standard for diagnosing E. vermicularis infection is by visualizing the worms directly or by examination of the parasitic eggs under a microscope. The Scotch tape test is a simple, inexpensive, and quick way for confirming the infection. It is performed by doubling clear cellophane Scotch tape onto a wooden stick so that the sticky side points outward and pressing it against the perianal skin. The kidney‐bean‐shaped eggs (50 25 m) will stick to the tape and can then be directly visualized under a microscope. Pinworms are most active during the night, and eggs are deposited around the perianal region and are best recovered before defecation, early in the morning. The sensitivity of this test is 90% if done on 3 consecutive mornings and goes up to 99% when performed on 5 consecutive mornings.2, 3 Female adult worms are pin‐shaped, about 813 mm long, and white in color. They may be seen by direct visualization in the perianal region or more invasively by an anoscopic or colonoscopic examination. However, endoscopic examination may sometimes give false‐negative results as the worms are small, (ie, only a few millimeters in length) and may be missed if the endoscopist is not actively looking for them.

A single oral dose of benzimidazoles (100 mg of mebendazole or 400 mg of albendazole) results in a cure of rate of 95% and 100%, respectively. Despite the high initial cure rates, reinfection remains common; hence, a second dose 12 weeks after the initial treatment is often given to prevent it.4, 5 Pyrantel pamoate and piperazine are alternate treatments. However, they have lower efficacy and are more toxic than benzimidazoles.

Close contacts such as household members are often concurrently infected, and treatment of the remaining household members or of the group institution is also indicated. All bedding and clothes should be laundered. Personal hygiene such as fingernail clipping, frequent hand washing, and bathing should also be encouraged.

Although the pinworm's entire life cycle is in the human intestinal tract, gastrointestinal symptoms have seldom been reported. However, this may be because of underreporting. Given the increasing number of patients living in institutionalized environments such as nursing homes and assisted living, it is important to consider the possibility of E. vermicularis infection early on in a diagnostic workup of patients presenting with symptoms of colitis, even when not accompanied by anal pruritis. In a patient presenting with symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease with histopathological evaluation of nonspecific colitis should prompt clinicians to consider E. vermicularis infection.6 On the other hand, in patients who fail to respond to antiparasitic therapy or those who present with weight loss, change in bowel habits, or melena, colonscopic examination is warranted. Considering pinworm infection early during evaluation of nonspecific abdominal complaints may avoid an unnecessary and expensive diagnostic workup.

KEY POINTS

-

Recognize early on that Enterobius vermicularis infection is an important differential diagnosis for patients presenting with symptoms of colitis, thus avoiding unnecessary, expensive, and potentially harmful invasive testing.

-

Recognize that a simple and inexpensive Scotch tape test and/or direct visualization is an easy and effective way of confirming diagnosis and that stool examination may be unhelpful.

-

Recognize that reinfection may be prevented using a second dose of the antiparasitic drug.

- .The pinworm, Enterobius vermicularis.Prim Care.1991;18:13–24.

- ,,,,.Prevalence of intestinal parasites in three socioeconomically‐different regions of Sivas, Turkey.J Health Popul Nutr.2005;23:184–191.

- ,,,.Pinworm infection.Gastrointest Endosc.2001;53:210.

- ,,.Mebendazole (R 17635) in enterobiasis. A clinical trial in mental retardates.Chemotherapy.1975;21:255–260.

- ,,, et al.Field trials on the efficacy of albendazole composite against intestinal nematodiasis.Chung Kuo Chi Sheng Chung Hsueh Yu Chi Sheng Chung Ping Tsa Chih.1998;16:1–5.

- ,,.Enterobius vermicularis and colitis in children.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.2006;43:610–612.

An 84‐year‐old female patient with hypertension, osteoarthritis, hypothyroidism, and remote breast cancer was admitted with complaints of generalized abdominal pain of 2 months' duration. Pain was described as noncolicky in nature and was associated with diarrhea. She reported 78 daily episodes of watery, non‐foul‐smelling diarrhea. She denied any nausea, vomiting, fever, joint pains, oral ulcers, eye redness, stool incontinence, melena, hematochezia, or weight loss. There was no history of recent travel, antibiotic use, or exposure to sick contacts. She had no risk factors for HIV infection or other sexually transmitted infections. Her social history was significant for dining out on a regular basis and living in an assisted living facility. However, she denied any relationship between her abdominal symptoms and any particular food intake or with bowel movements. She denied any anal pruritis but reported seeing white squiggly things on tissue paper after bowel movements. She denied use of over‐the‐counter laxatives or herbal supplements. None of her prescription medications had diarrhea as a major side effect. Her social history was unremarkable for smoking, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. There were no prior abdominal surgeries. The patient's physical exam showed normal vitals on presentation and was unremarkable except for vague, generalized abdominal tenderness with no involuntary guarding or rebound pain. Her initial laboratory evaluation showed normal complete blood counts with no eosinophilia and normal serum electrolytes and liver and thyroid panel. Acute‐phase reactants, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C‐reactive protein were not elevated. Stool evaluation was unremarkable for Clostridium difficile toxin, fat droplets, leukocytes, erythrocytes, ova, parasites, or any bacterial growth on cultures. Computed tomography scans of the abdomen and pelvis were nonrevealing. Her colonoscopic examination 1 year prior was significant only for diverticulosis.1, 2

The patient was treated with loperamide as an outpatient with no relief. She was then admitted to the hospital for further diagnostic workup. Hospital workup included a Scotch tape test, which showed adult pinworms. She was treated with a single dose of 400 mg of albendazole with complete resolution of her symptoms within 2 days. No further workup was done. Patient was discharged with advice to contact her primary care doctor for reevaluation if symptoms recurred. However, the patient remained symptom free 1 year after discharge.

DISCUSSION

Enterobius vermicularis is a parasite that infects 2040 million people annually in the United States and about 200 million people worldwide. Equal infection rates are seen in all races, socioeconomic classes, and cultures.1 It is more prevalent among those in crowded living conditions. Humans are the primary natural host for the parasite, although it has been documented in cockroaches and primates. Transmission occurs via the feco‐oral route or via airborne eggs that are dislodged from contaminated clothing or bed linen. Its life cycle begins with parasite eggs hatching in the duodenum, usually within 6 hours of ingestion. They mature into adults in as little as 2 weeks and have a life span of approximately 2 months. Enterobius vermicularis normally inhabits distal small bowel including the terminal ileum, cecum, and vermiform appendix, as well as the proximal ascending colon. After copulation, an adult female will migrate to the perineum, often at night, and lay an average of 10,00015,000 eggs. These eggs mature in about 6 hours and are then transmitted to a new host by the feco‐oral route. The worms live mainly in the intestinal lumen and do not invade tissue. Hence, pinworm infections, unlike many other parasitic infections, are rarely associated with serum eosinophilia or elevated serum IgE levels.

E. vermicularis is generally considered to be an innocuous parasite. Perianal pruritis, especially during the nighttime, is the most common symptom. Patients may develop secondary bacterial infection of the irritated anal skin. Rarely, E. vermicularis infection may result in a life‐threatening illness. A literature review showed pinworm infection to be an infrequent cause of eosinophilic enterocolitis, appendicitis, intestinal obstruction, intestinal perforation, hepatic infection, urinary tract infection, sialoadenitis, salpingitis, enterocolitis, eosinophilic ileocolitis, vulvovaginitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, conditions mimicking inflammatory bowel diseases, perianal abscesses, and perianal granulomas. In a retrospective review of 180 colonoscopies done on patients with rectal bleeding or suspected inflammatory bowel disease, E. vermicularis was identified macroscopically in 31 cases (17.2%). Data collected on 23 of these cases showed that symptoms were present for a mean of 17 months; the symptoms with the highest frequency were abdominal pain (73%), rectal bleeding (62%), chronic diarrhea (50%), and weight loss (42%). None of these patients experienced perianal pruritis or developed inflammatory bowel disease during the follow‐up period of up to 5 years, although 21 patients demonstrated histopathological evidence of nonspecific colitis.6

The gold standard for diagnosing E. vermicularis infection is by visualizing the worms directly or by examination of the parasitic eggs under a microscope. The Scotch tape test is a simple, inexpensive, and quick way for confirming the infection. It is performed by doubling clear cellophane Scotch tape onto a wooden stick so that the sticky side points outward and pressing it against the perianal skin. The kidney‐bean‐shaped eggs (50 25 m) will stick to the tape and can then be directly visualized under a microscope. Pinworms are most active during the night, and eggs are deposited around the perianal region and are best recovered before defecation, early in the morning. The sensitivity of this test is 90% if done on 3 consecutive mornings and goes up to 99% when performed on 5 consecutive mornings.2, 3 Female adult worms are pin‐shaped, about 813 mm long, and white in color. They may be seen by direct visualization in the perianal region or more invasively by an anoscopic or colonoscopic examination. However, endoscopic examination may sometimes give false‐negative results as the worms are small, (ie, only a few millimeters in length) and may be missed if the endoscopist is not actively looking for them.

A single oral dose of benzimidazoles (100 mg of mebendazole or 400 mg of albendazole) results in a cure of rate of 95% and 100%, respectively. Despite the high initial cure rates, reinfection remains common; hence, a second dose 12 weeks after the initial treatment is often given to prevent it.4, 5 Pyrantel pamoate and piperazine are alternate treatments. However, they have lower efficacy and are more toxic than benzimidazoles.

Close contacts such as household members are often concurrently infected, and treatment of the remaining household members or of the group institution is also indicated. All bedding and clothes should be laundered. Personal hygiene such as fingernail clipping, frequent hand washing, and bathing should also be encouraged.

Although the pinworm's entire life cycle is in the human intestinal tract, gastrointestinal symptoms have seldom been reported. However, this may be because of underreporting. Given the increasing number of patients living in institutionalized environments such as nursing homes and assisted living, it is important to consider the possibility of E. vermicularis infection early on in a diagnostic workup of patients presenting with symptoms of colitis, even when not accompanied by anal pruritis. In a patient presenting with symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease with histopathological evaluation of nonspecific colitis should prompt clinicians to consider E. vermicularis infection.6 On the other hand, in patients who fail to respond to antiparasitic therapy or those who present with weight loss, change in bowel habits, or melena, colonscopic examination is warranted. Considering pinworm infection early during evaluation of nonspecific abdominal complaints may avoid an unnecessary and expensive diagnostic workup.

KEY POINTS

-

Recognize early on that Enterobius vermicularis infection is an important differential diagnosis for patients presenting with symptoms of colitis, thus avoiding unnecessary, expensive, and potentially harmful invasive testing.

-

Recognize that a simple and inexpensive Scotch tape test and/or direct visualization is an easy and effective way of confirming diagnosis and that stool examination may be unhelpful.

-

Recognize that reinfection may be prevented using a second dose of the antiparasitic drug.

An 84‐year‐old female patient with hypertension, osteoarthritis, hypothyroidism, and remote breast cancer was admitted with complaints of generalized abdominal pain of 2 months' duration. Pain was described as noncolicky in nature and was associated with diarrhea. She reported 78 daily episodes of watery, non‐foul‐smelling diarrhea. She denied any nausea, vomiting, fever, joint pains, oral ulcers, eye redness, stool incontinence, melena, hematochezia, or weight loss. There was no history of recent travel, antibiotic use, or exposure to sick contacts. She had no risk factors for HIV infection or other sexually transmitted infections. Her social history was significant for dining out on a regular basis and living in an assisted living facility. However, she denied any relationship between her abdominal symptoms and any particular food intake or with bowel movements. She denied any anal pruritis but reported seeing white squiggly things on tissue paper after bowel movements. She denied use of over‐the‐counter laxatives or herbal supplements. None of her prescription medications had diarrhea as a major side effect. Her social history was unremarkable for smoking, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. There were no prior abdominal surgeries. The patient's physical exam showed normal vitals on presentation and was unremarkable except for vague, generalized abdominal tenderness with no involuntary guarding or rebound pain. Her initial laboratory evaluation showed normal complete blood counts with no eosinophilia and normal serum electrolytes and liver and thyroid panel. Acute‐phase reactants, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C‐reactive protein were not elevated. Stool evaluation was unremarkable for Clostridium difficile toxin, fat droplets, leukocytes, erythrocytes, ova, parasites, or any bacterial growth on cultures. Computed tomography scans of the abdomen and pelvis were nonrevealing. Her colonoscopic examination 1 year prior was significant only for diverticulosis.1, 2

The patient was treated with loperamide as an outpatient with no relief. She was then admitted to the hospital for further diagnostic workup. Hospital workup included a Scotch tape test, which showed adult pinworms. She was treated with a single dose of 400 mg of albendazole with complete resolution of her symptoms within 2 days. No further workup was done. Patient was discharged with advice to contact her primary care doctor for reevaluation if symptoms recurred. However, the patient remained symptom free 1 year after discharge.

DISCUSSION

Enterobius vermicularis is a parasite that infects 2040 million people annually in the United States and about 200 million people worldwide. Equal infection rates are seen in all races, socioeconomic classes, and cultures.1 It is more prevalent among those in crowded living conditions. Humans are the primary natural host for the parasite, although it has been documented in cockroaches and primates. Transmission occurs via the feco‐oral route or via airborne eggs that are dislodged from contaminated clothing or bed linen. Its life cycle begins with parasite eggs hatching in the duodenum, usually within 6 hours of ingestion. They mature into adults in as little as 2 weeks and have a life span of approximately 2 months. Enterobius vermicularis normally inhabits distal small bowel including the terminal ileum, cecum, and vermiform appendix, as well as the proximal ascending colon. After copulation, an adult female will migrate to the perineum, often at night, and lay an average of 10,00015,000 eggs. These eggs mature in about 6 hours and are then transmitted to a new host by the feco‐oral route. The worms live mainly in the intestinal lumen and do not invade tissue. Hence, pinworm infections, unlike many other parasitic infections, are rarely associated with serum eosinophilia or elevated serum IgE levels.

E. vermicularis is generally considered to be an innocuous parasite. Perianal pruritis, especially during the nighttime, is the most common symptom. Patients may develop secondary bacterial infection of the irritated anal skin. Rarely, E. vermicularis infection may result in a life‐threatening illness. A literature review showed pinworm infection to be an infrequent cause of eosinophilic enterocolitis, appendicitis, intestinal obstruction, intestinal perforation, hepatic infection, urinary tract infection, sialoadenitis, salpingitis, enterocolitis, eosinophilic ileocolitis, vulvovaginitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, conditions mimicking inflammatory bowel diseases, perianal abscesses, and perianal granulomas. In a retrospective review of 180 colonoscopies done on patients with rectal bleeding or suspected inflammatory bowel disease, E. vermicularis was identified macroscopically in 31 cases (17.2%). Data collected on 23 of these cases showed that symptoms were present for a mean of 17 months; the symptoms with the highest frequency were abdominal pain (73%), rectal bleeding (62%), chronic diarrhea (50%), and weight loss (42%). None of these patients experienced perianal pruritis or developed inflammatory bowel disease during the follow‐up period of up to 5 years, although 21 patients demonstrated histopathological evidence of nonspecific colitis.6

The gold standard for diagnosing E. vermicularis infection is by visualizing the worms directly or by examination of the parasitic eggs under a microscope. The Scotch tape test is a simple, inexpensive, and quick way for confirming the infection. It is performed by doubling clear cellophane Scotch tape onto a wooden stick so that the sticky side points outward and pressing it against the perianal skin. The kidney‐bean‐shaped eggs (50 25 m) will stick to the tape and can then be directly visualized under a microscope. Pinworms are most active during the night, and eggs are deposited around the perianal region and are best recovered before defecation, early in the morning. The sensitivity of this test is 90% if done on 3 consecutive mornings and goes up to 99% when performed on 5 consecutive mornings.2, 3 Female adult worms are pin‐shaped, about 813 mm long, and white in color. They may be seen by direct visualization in the perianal region or more invasively by an anoscopic or colonoscopic examination. However, endoscopic examination may sometimes give false‐negative results as the worms are small, (ie, only a few millimeters in length) and may be missed if the endoscopist is not actively looking for them.

A single oral dose of benzimidazoles (100 mg of mebendazole or 400 mg of albendazole) results in a cure of rate of 95% and 100%, respectively. Despite the high initial cure rates, reinfection remains common; hence, a second dose 12 weeks after the initial treatment is often given to prevent it.4, 5 Pyrantel pamoate and piperazine are alternate treatments. However, they have lower efficacy and are more toxic than benzimidazoles.

Close contacts such as household members are often concurrently infected, and treatment of the remaining household members or of the group institution is also indicated. All bedding and clothes should be laundered. Personal hygiene such as fingernail clipping, frequent hand washing, and bathing should also be encouraged.

Although the pinworm's entire life cycle is in the human intestinal tract, gastrointestinal symptoms have seldom been reported. However, this may be because of underreporting. Given the increasing number of patients living in institutionalized environments such as nursing homes and assisted living, it is important to consider the possibility of E. vermicularis infection early on in a diagnostic workup of patients presenting with symptoms of colitis, even when not accompanied by anal pruritis. In a patient presenting with symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease with histopathological evaluation of nonspecific colitis should prompt clinicians to consider E. vermicularis infection.6 On the other hand, in patients who fail to respond to antiparasitic therapy or those who present with weight loss, change in bowel habits, or melena, colonscopic examination is warranted. Considering pinworm infection early during evaluation of nonspecific abdominal complaints may avoid an unnecessary and expensive diagnostic workup.

KEY POINTS

-

Recognize early on that Enterobius vermicularis infection is an important differential diagnosis for patients presenting with symptoms of colitis, thus avoiding unnecessary, expensive, and potentially harmful invasive testing.

-

Recognize that a simple and inexpensive Scotch tape test and/or direct visualization is an easy and effective way of confirming diagnosis and that stool examination may be unhelpful.

-

Recognize that reinfection may be prevented using a second dose of the antiparasitic drug.

- .The pinworm, Enterobius vermicularis.Prim Care.1991;18:13–24.

- ,,,,.Prevalence of intestinal parasites in three socioeconomically‐different regions of Sivas, Turkey.J Health Popul Nutr.2005;23:184–191.

- ,,,.Pinworm infection.Gastrointest Endosc.2001;53:210.

- ,,.Mebendazole (R 17635) in enterobiasis. A clinical trial in mental retardates.Chemotherapy.1975;21:255–260.

- ,,, et al.Field trials on the efficacy of albendazole composite against intestinal nematodiasis.Chung Kuo Chi Sheng Chung Hsueh Yu Chi Sheng Chung Ping Tsa Chih.1998;16:1–5.

- ,,.Enterobius vermicularis and colitis in children.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.2006;43:610–612.

- .The pinworm, Enterobius vermicularis.Prim Care.1991;18:13–24.

- ,,,,.Prevalence of intestinal parasites in three socioeconomically‐different regions of Sivas, Turkey.J Health Popul Nutr.2005;23:184–191.

- ,,,.Pinworm infection.Gastrointest Endosc.2001;53:210.

- ,,.Mebendazole (R 17635) in enterobiasis. A clinical trial in mental retardates.Chemotherapy.1975;21:255–260.

- ,,, et al.Field trials on the efficacy of albendazole composite against intestinal nematodiasis.Chung Kuo Chi Sheng Chung Hsueh Yu Chi Sheng Chung Ping Tsa Chih.1998;16:1–5.

- ,,.Enterobius vermicularis and colitis in children.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.2006;43:610–612.

In the Literature

Hematocrit and Perioperative Mortality

Wu WC, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, et al. Preoperative hematocrit levels and postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2007 Jun 13;297(22):2481-2488.

Several studies have outlined the risk of preoperative anemia prior to noncardiac surgery in elderly patients. These studies have not linked anemia to risk of death unless cardiac disease is present.

Anemia management remains a challenge for many hospitals and is the most important predictor of the need for blood transfusion. Transfusion increases morbidity and mortality in the perioperative setting. At the same time, little is known about the risks of polycythemia in this setting.

This retrospective cohort study used the Veterans’ Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database of 310,311 veterans 65 or older from 132 VA hospitals. It explores the relationship between abnormal levels of hematocrit and adverse events among elderly surgical patients.

The data suggest an incremental relationship between positive and negative deviation of hematocrit levels with 30-day postoperative mortality in patients 65 and older. Specifically, the study found a 1.6% increase (95% confidence interval, 1.1%-2.2%) in 30-day mortality for every percentage point of increase or decrease in hematocrit from the normal range.

Because this is an observational study of anemia and adverse events, no causal relationship can be established from this data. Hospitalists involved in perioperative care should be careful about drawing conclusions from this study alone and should not necessarily plan interventions to treat abnormal levels of hematocrit without carefully considering the risks and benefits of intervention.

Prognostic Utility of Pre-operative BNP

Feringa HH, Schouten O, Dunkelgrun M, et al. Plasma N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide as long term prognostic marker after major vascular surgery. Heart. 2007 Feb;93(2):226-231.

Traditional stratification of patients at high risk for cardiac complications and undergoing noncardiac surgery has included clinical risk index scoring and pre-operative stress testing. It is unclear if cardiac biomarkers can be used in conjunction with these measures to improve the identification of patients at risk.

Feringa and colleagues addressed this question by looking prospectively at 335 patients undergoing major vascular surgery over a two-year period. The mean age of patients was 62.2 years; 46% of patients underwent abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, and the remaining 54% received lower-extremity revascularization.

Patients had cardiac risk scores calculated based on the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), and all patients had dobutamine stress echocardiogram (DSE) to assess for stress-induced ischemia. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) was measured at a mean of 12 days before surgery. Patients were followed for all-cause mortality and post-op death for a mean follow-up time of 14 months.

The authors found that NT-pro BNP performed better than the RCRI and DSE for predicting six-month mortality and cardiac events. An NT-pro BNP cut-off level of 319 ng/l was identified as optimal for predicting six-month mortality and cardiac events with 69% sensitivity and 70% specificity for mortality. Patients with levels 319 mg/l had a lower survival during the follow up period (p<0.0001).

Based on this prospective study, it appears that a preoperative elevated NT-Pro BNP is associated with long-term mortality and morbidity and could be used as an additional risk-stratification tool along with clinical risk scoring and stress testing.

Utility of Combination Medications in COPD

Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, et al. Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Feb 19;146:545-555

The appropriateness of multiple long-acting inhaled medications in treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is poorly studied. This study evaluated whether combining tiotropium with fluticasone-salmeterol or with salmeterol alone improves clinical outcomes in adult patients with moderate to severe COPD, as compared with tiotropium plus placebo.

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was set in academic and community medical centers in Canada. Researchers monitored 449 patients in the three parallel treatment groups for COPD exacerbations for 52 weeks. Analysis was done on an intention-to-treat basis. The rate of COPD exacerbations within the follow-up period (the primary outcome) was not significantly different among the three treatment groups. However, secondary outcomes, such as rates for hospitalization for COPD exacerbations, all-cause hospitalizations, health-related quality of life and lung function were significantly improved in the group receiving tiotropium and fluticasone-salmeterol.

A notable limitation was that more subjects stopped taking the study medications in the tiotropium-placebo and the tiotropium-salmeterol group. Many crossed over to treatments with inhaled corticosteroids or beta-agonists.

The results are in contrast to current guidelines, which recommend adding inhaled steroids to reduce exacerbations in moderate to severe COPD. Whether these results are due to differing statistical analysis among studies remains unclear. The authors postulate that reduction in secondary outcomes may be related to fluticasone reducing the severity of exacerbations rather than the actual number.

COPD exacerbations are among the most common diagnoses encountered by hospitalists. Most patients are treated with multiple inhaled medications to optimize their pulmonary status. Polypharmacy and the added financial burdens on the patient (particularly the elderly) are important considerations when deciding discharge medications, and the evidence of efficacy for combination inhaled medications had not been assessed as a clinical outcome prior to this study.

Benefits of Rapid Response Teams

Winters BD, Pham JC, Hunt EA et al. Rapid response systems: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2007 May;35(5):1238-1243.

Although the Institute for Healthcare Improvement has endorsed rapid response teams, and many hospitalist groups are involved with such systems, quality research is lacking.

Following up on the 2006 “First Consensus Conference on Medical Emergency Teams,” this meta-analysis sought to evaluate current literature to identify the effect of rapid response systems (RRS) on rates of hospital mortality and cardiac arrest.

The authors included randomized trials and observational studies in their analysis. Only eight studies met their inclusion criteria (six observational studies, one multicenter randomized trial, and one single-center randomized trial).

The pooled results did not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit of rapid-response systems in rates of hospital mortality. When rates of in-hospital cardiac arrest were analyzed, there was a weak finding in support of RRS, with the relative risk of 0.70 (confidence interval 0.56-0.92) in favor of RRSs. But the confidence interval was wide, and there was substantial heterogeneity among the included studies.

The authors conclude that “it seems premature to declare RRS as the standard of care,” and that data are lacking to justify any particular implementation scheme or composition of RRS or to support the cost-effectiveness of RRS.

Finally, they recognized the need for larger, better-designed randomized trials. However, in an accompanying editorial, Michael DeVita, MD—a pioneer in the development of RRS—rejects the use of techniques of evidence-based medicine such as multicenter trials and meta-analysis in assessing the utility of RRS. Dr. DeVita essentially says that changing the systems and culture of care within the hospital to accommodate patients with unmet critical needs must be effective in improving outcomes.

This meta-analysis is hindered by the suboptimal quality and homogeneity of studies available for assessment. Hospitalists should be aware of the limitations of the data and literature, as well as the empirical arguments raised by Dr. DeVita, when considering involvement in or designing RRS. TH

CLASSIC LIT

Perioperative Statins

Kapoor AS, Kanji H, Buckingham J, et al. Strength of evidence for perioperative use of statins to reduce cardiovascular risk: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2006 Nov 6;333(7579):1149.

Recent literature and randomized trials have claimed statins decrease morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular events in patients with or at high risk of coronary artery disease. This meta-analysis sought to determine the strength of evidence leading to the recommendations that perioperative statins be used to reduce perioperative cardiovascular events.

The literature search and exclusion criteria identified 18 studies. Two were randomized controlled trials (n=177), 15 were cohort studies (n=799,632), and one was a case-control study (n=480). Of these, 12 studies enrolled patients undergoing noncardiac vascular surgery, four enrolled patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery, and two enrolled patients undergoing various surgical procedures. The 16 nonrandomized studies were rated good. The two randomized trials were rated five and two out of five using the Jadad quality scores.

The results showed that in the randomized trials the summary odds ratio (OR) for death or acute coronary syndrome during the perioperative period with statin use was 0.26 (95% confidence interval 0.07 to 0.99), but this was based on only 13 events in 177 patients and cannot be considered conclusive. In the cohort studies, the OR was 0.70 (95% confidence interval 0.57 to 0.87). Although the pooled cohort data provided a statistically significant result, these cannot be considered conclusive because the statins were not randomly allocated and the results from retrospective studies were more impressive (OR 0.65, 95% confidence interval 0.50 to 0.84) than those in the prospective cohorts (OR 0.91, 95% confidence interval 0.65 to 1.27) and dose, duration, and safety of statin use were not reported.

Limitations of this meta-analysis include that none of the studies reported patient compliance or doses of statins or cholesterol levels before and after surgery, and few reported the duration of therapy before surgery or the which statin was used. Thus, the authors were unable to demonstrate a dose-response association. They were also unable to ascertain if the benefits seen with statins in the observational studies were exaggerated owing to inclusion of patients in the nonstatin group who had their statins stopped prior to surgery, because acute statin withdrawal may be associated with cardiac events.

The authors concluded that although their meta-analysis—which included data from more than 800,000 patients—suggests considerable benefits from perioperative statin use, the evidence from the randomized trials is not definitive. They advocate only that statins be started preoperatively in eligible patients (e.g., patients with coronary artery disease, multiple cardiac risk factors, elevated LDL) who would warrant statin therapy for medical reasons independent of the proposed operation.

Electronic Alerts to Prevent Hospital-acquired VTE

Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 10;352(10):969-977

Surveys conducted in North America and Europe have shown that prophylaxis against deep venous thrombosis (DVT) has been consistently underused in hospitalized patients despite consensus guidelines. Studies involving continuing medical education and computerized electronic alerts have shown that physician use of prophylaxis improves when such processes are in place, but have not demonstrated that they can reduce the rate of DVT.

A computer program was developed to identify consecutive hospitalized patients at increased risk for DVT. The program used eight common risk factors to determine each patient’s risk profile for DVT and each risk factor was assigned a score. A cumulative score of four or higher was used to determine patients at high risk for DVT. The computer alert program was screened daily to identify patients whose score increased to four or higher after admission into the hospital. If the cumulative risk score was at least four, the computer program reviewed the current electronic orders and active medications for the use of DVT prophylaxis.

In the study, 2,506 consecutive adult patients were identified as high risk for DVT. Further,1,255 were randomized to the intervention group—in which the responsible physician received one electronic alert about the risk of DVT—and 1,251 patients were randomized to the control group in which no alert was issued. The 120 physicians involved took care of patients in the intervention and control groups. Physicians responsible for the control group were not aware that patients were being followed for clinical events. When physicians received alerts, they had to acknowledge them and could either withhold prophylaxis or order it on the same computer screen.

Patients were followed for 90 days after the index hospitalization. The primary end point was clinically apparent DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE). Safety end points included mortality at 30 days, and the rate of hemorrhagic events at 90 days.

The results showed that prophylactic measures were ordered for 421 of the 1,255 patients in the intervention group (33.5%) and 182 of the 1,251 patients in the control group (14.5%, p <0.001). There were higher rates of both mechanical (10% versus 1.5%, p<0.001) and pharmacological (23.6% versus 13.0%, p<0.001) prophylaxis in the intervention group. The primary end point of DVT or PE at 90 days occurred in 61 patients in the intervention group (4.9%) as compared with 103 patients in the control group (8.2%).

The computer alert reduced the risk of events at 90 days by 41% (HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.81; P=0.001). Of the patients who received prophylaxis 5.1% had DVT or PE compared with 7.0% of those who did not. In the intervention group, DVT or PE occurred in 20 of 421 (4.8%) patients who received prophylaxis compared with 41 of 834 (4.9%) who did not receive any. In the control group, the same numbers were 11 of 182 (6.0%) and 91 of 1,069 (8.5%).

Some of this benefit might be attributed to the additional preventive measures such as physiotherapy and early ambulation in patients assigned to the intervention group. Diagnostic bias also could have played into the results. Not all patients were screened for VTE, and it is likely that symptomatic patients without prophylaxis were screened more frequently than symptomatic patients with prophylaxis. Because physicians took care of both the control and intervention group, alerts received by physicians in the control group could have influenced their decision in the control group as well.

The authors concluded that instituting computer alerts markedly reduced the rates of DVT or PE in hospitalized patients.

Hematocrit and Perioperative Mortality

Wu WC, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, et al. Preoperative hematocrit levels and postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2007 Jun 13;297(22):2481-2488.

Several studies have outlined the risk of preoperative anemia prior to noncardiac surgery in elderly patients. These studies have not linked anemia to risk of death unless cardiac disease is present.

Anemia management remains a challenge for many hospitals and is the most important predictor of the need for blood transfusion. Transfusion increases morbidity and mortality in the perioperative setting. At the same time, little is known about the risks of polycythemia in this setting.

This retrospective cohort study used the Veterans’ Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database of 310,311 veterans 65 or older from 132 VA hospitals. It explores the relationship between abnormal levels of hematocrit and adverse events among elderly surgical patients.

The data suggest an incremental relationship between positive and negative deviation of hematocrit levels with 30-day postoperative mortality in patients 65 and older. Specifically, the study found a 1.6% increase (95% confidence interval, 1.1%-2.2%) in 30-day mortality for every percentage point of increase or decrease in hematocrit from the normal range.

Because this is an observational study of anemia and adverse events, no causal relationship can be established from this data. Hospitalists involved in perioperative care should be careful about drawing conclusions from this study alone and should not necessarily plan interventions to treat abnormal levels of hematocrit without carefully considering the risks and benefits of intervention.

Prognostic Utility of Pre-operative BNP

Feringa HH, Schouten O, Dunkelgrun M, et al. Plasma N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide as long term prognostic marker after major vascular surgery. Heart. 2007 Feb;93(2):226-231.

Traditional stratification of patients at high risk for cardiac complications and undergoing noncardiac surgery has included clinical risk index scoring and pre-operative stress testing. It is unclear if cardiac biomarkers can be used in conjunction with these measures to improve the identification of patients at risk.

Feringa and colleagues addressed this question by looking prospectively at 335 patients undergoing major vascular surgery over a two-year period. The mean age of patients was 62.2 years; 46% of patients underwent abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, and the remaining 54% received lower-extremity revascularization.

Patients had cardiac risk scores calculated based on the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), and all patients had dobutamine stress echocardiogram (DSE) to assess for stress-induced ischemia. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) was measured at a mean of 12 days before surgery. Patients were followed for all-cause mortality and post-op death for a mean follow-up time of 14 months.

The authors found that NT-pro BNP performed better than the RCRI and DSE for predicting six-month mortality and cardiac events. An NT-pro BNP cut-off level of 319 ng/l was identified as optimal for predicting six-month mortality and cardiac events with 69% sensitivity and 70% specificity for mortality. Patients with levels 319 mg/l had a lower survival during the follow up period (p<0.0001).

Based on this prospective study, it appears that a preoperative elevated NT-Pro BNP is associated with long-term mortality and morbidity and could be used as an additional risk-stratification tool along with clinical risk scoring and stress testing.

Utility of Combination Medications in COPD

Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, et al. Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Feb 19;146:545-555

The appropriateness of multiple long-acting inhaled medications in treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is poorly studied. This study evaluated whether combining tiotropium with fluticasone-salmeterol or with salmeterol alone improves clinical outcomes in adult patients with moderate to severe COPD, as compared with tiotropium plus placebo.

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was set in academic and community medical centers in Canada. Researchers monitored 449 patients in the three parallel treatment groups for COPD exacerbations for 52 weeks. Analysis was done on an intention-to-treat basis. The rate of COPD exacerbations within the follow-up period (the primary outcome) was not significantly different among the three treatment groups. However, secondary outcomes, such as rates for hospitalization for COPD exacerbations, all-cause hospitalizations, health-related quality of life and lung function were significantly improved in the group receiving tiotropium and fluticasone-salmeterol.

A notable limitation was that more subjects stopped taking the study medications in the tiotropium-placebo and the tiotropium-salmeterol group. Many crossed over to treatments with inhaled corticosteroids or beta-agonists.

The results are in contrast to current guidelines, which recommend adding inhaled steroids to reduce exacerbations in moderate to severe COPD. Whether these results are due to differing statistical analysis among studies remains unclear. The authors postulate that reduction in secondary outcomes may be related to fluticasone reducing the severity of exacerbations rather than the actual number.

COPD exacerbations are among the most common diagnoses encountered by hospitalists. Most patients are treated with multiple inhaled medications to optimize their pulmonary status. Polypharmacy and the added financial burdens on the patient (particularly the elderly) are important considerations when deciding discharge medications, and the evidence of efficacy for combination inhaled medications had not been assessed as a clinical outcome prior to this study.

Benefits of Rapid Response Teams

Winters BD, Pham JC, Hunt EA et al. Rapid response systems: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2007 May;35(5):1238-1243.

Although the Institute for Healthcare Improvement has endorsed rapid response teams, and many hospitalist groups are involved with such systems, quality research is lacking.

Following up on the 2006 “First Consensus Conference on Medical Emergency Teams,” this meta-analysis sought to evaluate current literature to identify the effect of rapid response systems (RRS) on rates of hospital mortality and cardiac arrest.

The authors included randomized trials and observational studies in their analysis. Only eight studies met their inclusion criteria (six observational studies, one multicenter randomized trial, and one single-center randomized trial).

The pooled results did not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit of rapid-response systems in rates of hospital mortality. When rates of in-hospital cardiac arrest were analyzed, there was a weak finding in support of RRS, with the relative risk of 0.70 (confidence interval 0.56-0.92) in favor of RRSs. But the confidence interval was wide, and there was substantial heterogeneity among the included studies.

The authors conclude that “it seems premature to declare RRS as the standard of care,” and that data are lacking to justify any particular implementation scheme or composition of RRS or to support the cost-effectiveness of RRS.

Finally, they recognized the need for larger, better-designed randomized trials. However, in an accompanying editorial, Michael DeVita, MD—a pioneer in the development of RRS—rejects the use of techniques of evidence-based medicine such as multicenter trials and meta-analysis in assessing the utility of RRS. Dr. DeVita essentially says that changing the systems and culture of care within the hospital to accommodate patients with unmet critical needs must be effective in improving outcomes.

This meta-analysis is hindered by the suboptimal quality and homogeneity of studies available for assessment. Hospitalists should be aware of the limitations of the data and literature, as well as the empirical arguments raised by Dr. DeVita, when considering involvement in or designing RRS. TH

CLASSIC LIT

Perioperative Statins

Kapoor AS, Kanji H, Buckingham J, et al. Strength of evidence for perioperative use of statins to reduce cardiovascular risk: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2006 Nov 6;333(7579):1149.

Recent literature and randomized trials have claimed statins decrease morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular events in patients with or at high risk of coronary artery disease. This meta-analysis sought to determine the strength of evidence leading to the recommendations that perioperative statins be used to reduce perioperative cardiovascular events.

The literature search and exclusion criteria identified 18 studies. Two were randomized controlled trials (n=177), 15 were cohort studies (n=799,632), and one was a case-control study (n=480). Of these, 12 studies enrolled patients undergoing noncardiac vascular surgery, four enrolled patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery, and two enrolled patients undergoing various surgical procedures. The 16 nonrandomized studies were rated good. The two randomized trials were rated five and two out of five using the Jadad quality scores.

The results showed that in the randomized trials the summary odds ratio (OR) for death or acute coronary syndrome during the perioperative period with statin use was 0.26 (95% confidence interval 0.07 to 0.99), but this was based on only 13 events in 177 patients and cannot be considered conclusive. In the cohort studies, the OR was 0.70 (95% confidence interval 0.57 to 0.87). Although the pooled cohort data provided a statistically significant result, these cannot be considered conclusive because the statins were not randomly allocated and the results from retrospective studies were more impressive (OR 0.65, 95% confidence interval 0.50 to 0.84) than those in the prospective cohorts (OR 0.91, 95% confidence interval 0.65 to 1.27) and dose, duration, and safety of statin use were not reported.

Limitations of this meta-analysis include that none of the studies reported patient compliance or doses of statins or cholesterol levels before and after surgery, and few reported the duration of therapy before surgery or the which statin was used. Thus, the authors were unable to demonstrate a dose-response association. They were also unable to ascertain if the benefits seen with statins in the observational studies were exaggerated owing to inclusion of patients in the nonstatin group who had their statins stopped prior to surgery, because acute statin withdrawal may be associated with cardiac events.

The authors concluded that although their meta-analysis—which included data from more than 800,000 patients—suggests considerable benefits from perioperative statin use, the evidence from the randomized trials is not definitive. They advocate only that statins be started preoperatively in eligible patients (e.g., patients with coronary artery disease, multiple cardiac risk factors, elevated LDL) who would warrant statin therapy for medical reasons independent of the proposed operation.

Electronic Alerts to Prevent Hospital-acquired VTE

Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 10;352(10):969-977

Surveys conducted in North America and Europe have shown that prophylaxis against deep venous thrombosis (DVT) has been consistently underused in hospitalized patients despite consensus guidelines. Studies involving continuing medical education and computerized electronic alerts have shown that physician use of prophylaxis improves when such processes are in place, but have not demonstrated that they can reduce the rate of DVT.

A computer program was developed to identify consecutive hospitalized patients at increased risk for DVT. The program used eight common risk factors to determine each patient’s risk profile for DVT and each risk factor was assigned a score. A cumulative score of four or higher was used to determine patients at high risk for DVT. The computer alert program was screened daily to identify patients whose score increased to four or higher after admission into the hospital. If the cumulative risk score was at least four, the computer program reviewed the current electronic orders and active medications for the use of DVT prophylaxis.

In the study, 2,506 consecutive adult patients were identified as high risk for DVT. Further,1,255 were randomized to the intervention group—in which the responsible physician received one electronic alert about the risk of DVT—and 1,251 patients were randomized to the control group in which no alert was issued. The 120 physicians involved took care of patients in the intervention and control groups. Physicians responsible for the control group were not aware that patients were being followed for clinical events. When physicians received alerts, they had to acknowledge them and could either withhold prophylaxis or order it on the same computer screen.

Patients were followed for 90 days after the index hospitalization. The primary end point was clinically apparent DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE). Safety end points included mortality at 30 days, and the rate of hemorrhagic events at 90 days.

The results showed that prophylactic measures were ordered for 421 of the 1,255 patients in the intervention group (33.5%) and 182 of the 1,251 patients in the control group (14.5%, p <0.001). There were higher rates of both mechanical (10% versus 1.5%, p<0.001) and pharmacological (23.6% versus 13.0%, p<0.001) prophylaxis in the intervention group. The primary end point of DVT or PE at 90 days occurred in 61 patients in the intervention group (4.9%) as compared with 103 patients in the control group (8.2%).

The computer alert reduced the risk of events at 90 days by 41% (HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.81; P=0.001). Of the patients who received prophylaxis 5.1% had DVT or PE compared with 7.0% of those who did not. In the intervention group, DVT or PE occurred in 20 of 421 (4.8%) patients who received prophylaxis compared with 41 of 834 (4.9%) who did not receive any. In the control group, the same numbers were 11 of 182 (6.0%) and 91 of 1,069 (8.5%).

Some of this benefit might be attributed to the additional preventive measures such as physiotherapy and early ambulation in patients assigned to the intervention group. Diagnostic bias also could have played into the results. Not all patients were screened for VTE, and it is likely that symptomatic patients without prophylaxis were screened more frequently than symptomatic patients with prophylaxis. Because physicians took care of both the control and intervention group, alerts received by physicians in the control group could have influenced their decision in the control group as well.

The authors concluded that instituting computer alerts markedly reduced the rates of DVT or PE in hospitalized patients.

Hematocrit and Perioperative Mortality

Wu WC, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, et al. Preoperative hematocrit levels and postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2007 Jun 13;297(22):2481-2488.

Several studies have outlined the risk of preoperative anemia prior to noncardiac surgery in elderly patients. These studies have not linked anemia to risk of death unless cardiac disease is present.

Anemia management remains a challenge for many hospitals and is the most important predictor of the need for blood transfusion. Transfusion increases morbidity and mortality in the perioperative setting. At the same time, little is known about the risks of polycythemia in this setting.

This retrospective cohort study used the Veterans’ Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database of 310,311 veterans 65 or older from 132 VA hospitals. It explores the relationship between abnormal levels of hematocrit and adverse events among elderly surgical patients.

The data suggest an incremental relationship between positive and negative deviation of hematocrit levels with 30-day postoperative mortality in patients 65 and older. Specifically, the study found a 1.6% increase (95% confidence interval, 1.1%-2.2%) in 30-day mortality for every percentage point of increase or decrease in hematocrit from the normal range.

Because this is an observational study of anemia and adverse events, no causal relationship can be established from this data. Hospitalists involved in perioperative care should be careful about drawing conclusions from this study alone and should not necessarily plan interventions to treat abnormal levels of hematocrit without carefully considering the risks and benefits of intervention.

Prognostic Utility of Pre-operative BNP

Feringa HH, Schouten O, Dunkelgrun M, et al. Plasma N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide as long term prognostic marker after major vascular surgery. Heart. 2007 Feb;93(2):226-231.

Traditional stratification of patients at high risk for cardiac complications and undergoing noncardiac surgery has included clinical risk index scoring and pre-operative stress testing. It is unclear if cardiac biomarkers can be used in conjunction with these measures to improve the identification of patients at risk.

Feringa and colleagues addressed this question by looking prospectively at 335 patients undergoing major vascular surgery over a two-year period. The mean age of patients was 62.2 years; 46% of patients underwent abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, and the remaining 54% received lower-extremity revascularization.

Patients had cardiac risk scores calculated based on the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), and all patients had dobutamine stress echocardiogram (DSE) to assess for stress-induced ischemia. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) was measured at a mean of 12 days before surgery. Patients were followed for all-cause mortality and post-op death for a mean follow-up time of 14 months.

The authors found that NT-pro BNP performed better than the RCRI and DSE for predicting six-month mortality and cardiac events. An NT-pro BNP cut-off level of 319 ng/l was identified as optimal for predicting six-month mortality and cardiac events with 69% sensitivity and 70% specificity for mortality. Patients with levels 319 mg/l had a lower survival during the follow up period (p<0.0001).

Based on this prospective study, it appears that a preoperative elevated NT-Pro BNP is associated with long-term mortality and morbidity and could be used as an additional risk-stratification tool along with clinical risk scoring and stress testing.

Utility of Combination Medications in COPD

Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, et al. Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Feb 19;146:545-555

The appropriateness of multiple long-acting inhaled medications in treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is poorly studied. This study evaluated whether combining tiotropium with fluticasone-salmeterol or with salmeterol alone improves clinical outcomes in adult patients with moderate to severe COPD, as compared with tiotropium plus placebo.

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was set in academic and community medical centers in Canada. Researchers monitored 449 patients in the three parallel treatment groups for COPD exacerbations for 52 weeks. Analysis was done on an intention-to-treat basis. The rate of COPD exacerbations within the follow-up period (the primary outcome) was not significantly different among the three treatment groups. However, secondary outcomes, such as rates for hospitalization for COPD exacerbations, all-cause hospitalizations, health-related quality of life and lung function were significantly improved in the group receiving tiotropium and fluticasone-salmeterol.

A notable limitation was that more subjects stopped taking the study medications in the tiotropium-placebo and the tiotropium-salmeterol group. Many crossed over to treatments with inhaled corticosteroids or beta-agonists.

The results are in contrast to current guidelines, which recommend adding inhaled steroids to reduce exacerbations in moderate to severe COPD. Whether these results are due to differing statistical analysis among studies remains unclear. The authors postulate that reduction in secondary outcomes may be related to fluticasone reducing the severity of exacerbations rather than the actual number.

COPD exacerbations are among the most common diagnoses encountered by hospitalists. Most patients are treated with multiple inhaled medications to optimize their pulmonary status. Polypharmacy and the added financial burdens on the patient (particularly the elderly) are important considerations when deciding discharge medications, and the evidence of efficacy for combination inhaled medications had not been assessed as a clinical outcome prior to this study.

Benefits of Rapid Response Teams

Winters BD, Pham JC, Hunt EA et al. Rapid response systems: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2007 May;35(5):1238-1243.

Although the Institute for Healthcare Improvement has endorsed rapid response teams, and many hospitalist groups are involved with such systems, quality research is lacking.

Following up on the 2006 “First Consensus Conference on Medical Emergency Teams,” this meta-analysis sought to evaluate current literature to identify the effect of rapid response systems (RRS) on rates of hospital mortality and cardiac arrest.

The authors included randomized trials and observational studies in their analysis. Only eight studies met their inclusion criteria (six observational studies, one multicenter randomized trial, and one single-center randomized trial).

The pooled results did not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit of rapid-response systems in rates of hospital mortality. When rates of in-hospital cardiac arrest were analyzed, there was a weak finding in support of RRS, with the relative risk of 0.70 (confidence interval 0.56-0.92) in favor of RRSs. But the confidence interval was wide, and there was substantial heterogeneity among the included studies.

The authors conclude that “it seems premature to declare RRS as the standard of care,” and that data are lacking to justify any particular implementation scheme or composition of RRS or to support the cost-effectiveness of RRS.

Finally, they recognized the need for larger, better-designed randomized trials. However, in an accompanying editorial, Michael DeVita, MD—a pioneer in the development of RRS—rejects the use of techniques of evidence-based medicine such as multicenter trials and meta-analysis in assessing the utility of RRS. Dr. DeVita essentially says that changing the systems and culture of care within the hospital to accommodate patients with unmet critical needs must be effective in improving outcomes.

This meta-analysis is hindered by the suboptimal quality and homogeneity of studies available for assessment. Hospitalists should be aware of the limitations of the data and literature, as well as the empirical arguments raised by Dr. DeVita, when considering involvement in or designing RRS. TH

CLASSIC LIT

Perioperative Statins

Kapoor AS, Kanji H, Buckingham J, et al. Strength of evidence for perioperative use of statins to reduce cardiovascular risk: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2006 Nov 6;333(7579):1149.

Recent literature and randomized trials have claimed statins decrease morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular events in patients with or at high risk of coronary artery disease. This meta-analysis sought to determine the strength of evidence leading to the recommendations that perioperative statins be used to reduce perioperative cardiovascular events.

The literature search and exclusion criteria identified 18 studies. Two were randomized controlled trials (n=177), 15 were cohort studies (n=799,632), and one was a case-control study (n=480). Of these, 12 studies enrolled patients undergoing noncardiac vascular surgery, four enrolled patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery, and two enrolled patients undergoing various surgical procedures. The 16 nonrandomized studies were rated good. The two randomized trials were rated five and two out of five using the Jadad quality scores.

The results showed that in the randomized trials the summary odds ratio (OR) for death or acute coronary syndrome during the perioperative period with statin use was 0.26 (95% confidence interval 0.07 to 0.99), but this was based on only 13 events in 177 patients and cannot be considered conclusive. In the cohort studies, the OR was 0.70 (95% confidence interval 0.57 to 0.87). Although the pooled cohort data provided a statistically significant result, these cannot be considered conclusive because the statins were not randomly allocated and the results from retrospective studies were more impressive (OR 0.65, 95% confidence interval 0.50 to 0.84) than those in the prospective cohorts (OR 0.91, 95% confidence interval 0.65 to 1.27) and dose, duration, and safety of statin use were not reported.

Limitations of this meta-analysis include that none of the studies reported patient compliance or doses of statins or cholesterol levels before and after surgery, and few reported the duration of therapy before surgery or the which statin was used. Thus, the authors were unable to demonstrate a dose-response association. They were also unable to ascertain if the benefits seen with statins in the observational studies were exaggerated owing to inclusion of patients in the nonstatin group who had their statins stopped prior to surgery, because acute statin withdrawal may be associated with cardiac events.

The authors concluded that although their meta-analysis—which included data from more than 800,000 patients—suggests considerable benefits from perioperative statin use, the evidence from the randomized trials is not definitive. They advocate only that statins be started preoperatively in eligible patients (e.g., patients with coronary artery disease, multiple cardiac risk factors, elevated LDL) who would warrant statin therapy for medical reasons independent of the proposed operation.

Electronic Alerts to Prevent Hospital-acquired VTE

Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 10;352(10):969-977

Surveys conducted in North America and Europe have shown that prophylaxis against deep venous thrombosis (DVT) has been consistently underused in hospitalized patients despite consensus guidelines. Studies involving continuing medical education and computerized electronic alerts have shown that physician use of prophylaxis improves when such processes are in place, but have not demonstrated that they can reduce the rate of DVT.

A computer program was developed to identify consecutive hospitalized patients at increased risk for DVT. The program used eight common risk factors to determine each patient’s risk profile for DVT and each risk factor was assigned a score. A cumulative score of four or higher was used to determine patients at high risk for DVT. The computer alert program was screened daily to identify patients whose score increased to four or higher after admission into the hospital. If the cumulative risk score was at least four, the computer program reviewed the current electronic orders and active medications for the use of DVT prophylaxis.

In the study, 2,506 consecutive adult patients were identified as high risk for DVT. Further,1,255 were randomized to the intervention group—in which the responsible physician received one electronic alert about the risk of DVT—and 1,251 patients were randomized to the control group in which no alert was issued. The 120 physicians involved took care of patients in the intervention and control groups. Physicians responsible for the control group were not aware that patients were being followed for clinical events. When physicians received alerts, they had to acknowledge them and could either withhold prophylaxis or order it on the same computer screen.

Patients were followed for 90 days after the index hospitalization. The primary end point was clinically apparent DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE). Safety end points included mortality at 30 days, and the rate of hemorrhagic events at 90 days.

The results showed that prophylactic measures were ordered for 421 of the 1,255 patients in the intervention group (33.5%) and 182 of the 1,251 patients in the control group (14.5%, p <0.001). There were higher rates of both mechanical (10% versus 1.5%, p<0.001) and pharmacological (23.6% versus 13.0%, p<0.001) prophylaxis in the intervention group. The primary end point of DVT or PE at 90 days occurred in 61 patients in the intervention group (4.9%) as compared with 103 patients in the control group (8.2%).

The computer alert reduced the risk of events at 90 days by 41% (HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.81; P=0.001). Of the patients who received prophylaxis 5.1% had DVT or PE compared with 7.0% of those who did not. In the intervention group, DVT or PE occurred in 20 of 421 (4.8%) patients who received prophylaxis compared with 41 of 834 (4.9%) who did not receive any. In the control group, the same numbers were 11 of 182 (6.0%) and 91 of 1,069 (8.5%).

Some of this benefit might be attributed to the additional preventive measures such as physiotherapy and early ambulation in patients assigned to the intervention group. Diagnostic bias also could have played into the results. Not all patients were screened for VTE, and it is likely that symptomatic patients without prophylaxis were screened more frequently than symptomatic patients with prophylaxis. Because physicians took care of both the control and intervention group, alerts received by physicians in the control group could have influenced their decision in the control group as well.

The authors concluded that instituting computer alerts markedly reduced the rates of DVT or PE in hospitalized patients.

Do all patients undergoing bariatric surgery need polysomnography to evaluate for obstructive sleep apnea?

In the Literature

Treat Atrial Flutter

Da Costa A, Thévenin J, Roche F, et al. Results from the Loire-Ardèche-Drôme-Isère-Puy-de-Dôme (LADIP) trial on atrial flutter, a multicentric prospective randomized study comparing amiodarone and radiofrequency ablation after the first episode of symptomatic atrial flutter. Circulation. 2006;114:1676-1681.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has high success rates in atrial flutter, and American College of Cardiology/American Hospital Association guidelines classify a first episode of well-tolerated atrial flutter as a class IIa indication for RFA treatment. The LADIP trial compared RFA with the current practice of electroosmotic flow (EOF) cardioversion plus amiodarone after a first episode of symptomatic atrial flutter.

One hundred and four consecutive patients with a documented first episode of atrial flutter were enrolled over a period of 39 months. Excluded from the study were patients under the age of 70, those who had had previous antiarrythmic treatment for atrial flutter, those who had an amiodarone contraindication, patients with New York Heart Association class IV heart failure, and those who had a history of heart block. All 52 patients in group I received RFA by a standard method. Fifty-one of the 52 patients in group II underwent intracardiac stimulation, followed, if necessary, by external or internal cardioversion. All patients in group II received amiodarone as well as vitamin K antagonists.

The patients were followed up in the outpatient department at one, three, six, 12, and 18 months after randomization and at the end of the study. At each visit, arrhythmic or cardiovascular events were recorded, and a 12-lead ECG was obtained. Patients were fitted with a Holter monitor for seven days if they had recurring palpitations or symptoms. The primary outcome studied was recurrence of symptomatic atrial flutter and occurrence of atrial fibrillation.

After a mean follow-up of 13+/-6 months, atrial flutter recurred in two of the 52 (3.8%) patients in group I and 15 of 51 (29.5%) patients in group II (P<0.0001). In group I, one patient required a second, successful ablation. All the patients who recurred in group II were successfully treated using RFA. The occurrence of significant symptomatic atrial fibrillation was 8% in both groups at the end of the first year. By the end of the study, two patients in group I and one patient in group II were in chronic atrial fibrillation. When all the episodes of atrial fibrillation were counted (including those patients whose episodes lasted <10 minutes but were documented with an event monitor), the groups did not differ significantly.

No procedure-related complications occurred in group I. In the amiodarone group, however, two patients developed hypothyroidism, one developed hyperthyroidism, and two patients had symptomatic sick sinus syndrome. There were a total of 14 deaths during the course of the study (six patients in group I and eight patients in group II); none were related to the study protocol.

This study is the largest to date showing the superiority of RFA to cardioversion plus amiodarone after the first episode of symptomatic atrial flutter. The long-term risk of subsequent atrial fibrillation was found to be similar to that of the amiodarone-treatment group. Because the mean age of patients in this study was 78, however, these findings cannot necessarily be extrapolated to younger patient populations. Further, oral amiodarone was used initially in this study. It can be argued that IV amiodarone is far more efficacious than oral forms in the acute setting. Because RFA is an invasive procedure, it is user-dependent and may be unfeasible in different care settings. Also, RFA might not be as appropriate for many symptomatic patients with atrial flutter and hemodynamic instability. Nevertheless, this study presents hospital-based physicians with an additional consideration in the acute care setting for patients with a first episode of atrial flutter.

A Transitional Care Intervention Trial

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822-1828.