User login

Standardization of the Discharge Process for Inpatient Hematology and Oncology Using Plan-Do-Study-Act Methodology Improves Follow-Up and Patient Hand-Off

Hematology and oncology patients are a complex patient population that requires timely follow-up to prevent clinical decompensation and delays in treatment. Previous reports have demonstrated that outpatient follow-up within 14 days is associated with decreased 30-day readmissions. The magnitude of this effect is greater for higher-risk patients.1 Therefore, patients being discharged from the hematology and oncology inpatient service should be seen by a hematology and oncology provider within 14 days of discharge. Patients who do not require close oncologic follow-up should be seen by a primary care provider (PCP) within this timeframe.

Background

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) identified the need to focus on quality improvement and patient safety with a 1999 report, To Err Is Human.2 Tremendous strides have been made in the areas of quality improvement and patient safety over the past 2 decades. In a 2013 report, the IOM further identified hematology and oncology care as an area of need due to a combination of growing demand, complexity of cancer and cancer treatment, shrinking workforce, and rising costs. The report concluded that cancer care is not as patient-centered, accessible, coordinated, or evidence based as it could be, with detrimental impacts on patients.3 Patients with cancer have been identified as a high-risk population for hospital readmissions.4,5 Lack of timely follow-up and failed hand-offs have been identified as factors contributing to poor outcomes at time of discharge.6-10

Upon internal review of baseline performance data, we identified areas needing improvement in the discharge process. These included time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, percent of patients with PCP appointments scheduled at time of discharge, and electronically alerts for the outpatient hematologist/oncologist to discharge summaries. It was determined that patients discharged from the inpatient service were seen a mean 17 days later by their outpatient hematology and oncology provider and the time to the follow-up appointment varied substantially, with some patients being seen several weeks to months after discharge. Furthermore, only 68% of patients had a primary care appointment scheduled at the time of discharge. These data along with review of data reported in the medical literature supported our initiative for improvement in the transition from inpatient to outpatient care for our hematology and oncology patients.

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement methodology was used to create and implement several interventions to standardize the discharge process for this patient population, with the primary goal of decreasing the mean time to hematology and oncology follow-up from 17 days by 12% to fewer than 14 days. Patients who do not require close oncologic follow-up should be seen by a PCP within this timeframe. Otherwise, PCP follow-up within at least 6 months should be made. Secondary aims included (1) an increase in scheduled PCP visits at time of discharge from 68% to > 90%; and (2) an increase in communication of the discharge summary via electronic alerting of the outpatient hematology and oncology physician from 20% to > 90%. Herein, we report our experience and results of this quality improvement initiative

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at Edward Hines Veteran Affairs Hospital in Hines, Illinois reviewed this single-center study and deemed it to be exempt from oversight. Using PDSA quality improvement methodology, a multidisciplinary team of hematology and oncology staff developed and implemented a standardized discharge process. The multidisciplinary team included a robust representation of inpatient and outpatient staff caring for the hematology and oncology patient population, including attending physicians, fellows, residents, advanced practice nurses, registered nurses, clinical pharmacists, patient care coordinators, clinic schedulers, clinical applications coordinators, quality support staff, and a systems redesign coach. Hospital leadership including chief of staff, chief of medicine, and chief of nursing participated as the management guidance team. Several interviews and group meetings were conducted and a multidisciplinary team collaboratively developed and implemented the interventions and monitored the results.

Outcome measures were identified, including time to hematology and oncology clinic visit, primary care follow-up scheduling, and communication of discharge to the outpatient hematology and oncology physician. Baseline data were collected and reviewed. The multidisciplinary team developed a process flow map to understand the steps and resources involved with the transition from inpatient to outpatient care. Gap analysis and root cause analysis were performed. A solutions approach was applied to develop interventions. Table 1 shows a summary of the identified problems, symptoms, associated causes, the interventions aimed to address the problems, and expected outcomes. Rotating resident physicians were trained through online and in-person education. The multidisciplinary team met intermittently to monitor outcomes, provide feedback, further refine interventions, and develop additional interventions.

PDSA Cycle 1

A standardized discharge process was developed in the form of guidelines and expectations. These include an explanation of unique features of the hematology and oncology service and expectations of medication reconciliation with emphasis placed on antiemetics, antimicrobial prophylaxis, and bowel regimen when appropriate, outpatient hematology and oncology follow-up within 14 days, primary care follow-up, communication with the outpatient hematology and oncology physician, written discharge instructions, and bedside teaching when appropriate.

PDSA Cycle 2

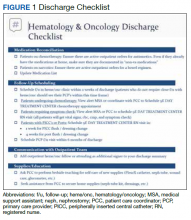

Based on team member feedback and further discussions, a discharge checklist was developed. This checklist was available online, reviewed in person, and posted in the team room for rotating residents to use for discharge planning and when discharging patients (Figure 1).

PDSA Cycle 3

Based on ongoing user feedback, group discussions, and data monitoring, the discharge checklist was further refined and updated. An electronic clinical decision support tool was developed and integrated into the electronic medical record (EMR) in the form of a discharge checklist note template directly linked to orders. The tool is a computerized patient record system (CPRS) note template that prompts users to select whether medications or return to clinic orders are needed and offers a menu of frequently used medications. If any of the selections are chosen within the note template, an order is generated automatically in the chart that requires only the user’s signature. Furthermore, the patient care coordinator reviews the prescribed follow-up and works with the medical support assistant to make these appointments. The physician is contacted only when an appointment cannot be made. Therefore, this tool allows many additional actions to be bypassed such as generating medication and return to clinic orders individually and calling schedulers to make follow-up appointments (Figure 2).

Data Analysis

All patients discharged during the 2-month period prior to and discharged after the implementation of the standardized process were reviewed. Patients who followed up with hematology and oncology at another facility, enrolled in hospice, or died during admission were excluded. Follow-up appointment scheduling data and communication between inpatient and outpatient providers were reviewed. Data were analyzed using XmR statistical process control chart and Fisher’s Exact Test using GraphPad. Control limits were calculated for each PDSA cycle as the mean ± the average of the moving range multiplied by 2.66. All data were included in the analysis.

Results

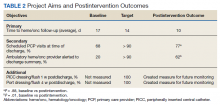

A total of 142 consecutive patients were reviewed from May 1, 2018 to August 31, 2018 and January 1, 2019 to April 30, 2019, including 58 patients prior to the intervention and 84 patients during PDSA cycles. There was a gap in data collection between September 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018 due to limited team member availability. All data were collected by 2 reviewers—a postgraduate year (PGY)-4 chief resident and a PGY-2 internal medicine resident. The median age of patients in the preintervention group was 72 years and 69 years in the postintervention group. All patients were men. Baseline data revealed a mean 17 days to hematology and oncology follow-up. Primary care visits were scheduled for 68% of patients at the time of discharge. The outpatient hematology and oncology physician was alerted electronically to the discharge summary for 20% of the patients (Table 2).

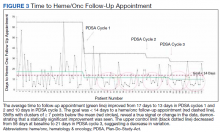

The primary endpoint of time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment improved to 13 days in PDSA cycles 1 and 2 and 10 days in PDSA cycle 3. The target of mean 14 days to follow-up was achieved. The statistical process control chart shows 5 shifts with clusters of ≥ 7 points below the mean revealing a true signal or change in the data and demonstrating that an improvement was seen (Figure 3). Furthermore, the statistical process control chart demonstrates upper control limit decreased from 58 days at baseline to 21 days in PDSA cycle 3, suggesting a decrease in variation.

Regarding secondary endpoints, the outpatient hematology and oncology attending physician and/or fellow was alerted electronically to the discharge summary for 62% of patients compared with 20% at baseline (P = .01), and primary care appointments were scheduled for 77% of patients after the intervention compared with 68% at baseline (P = .88) (Table 2).

Through ongoing meetings, discussions, and feedback, we identified additional objectives unique to this patient population that had no performance measurement. These included peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) care nursing visits scheduled 1 week after discharge and port care nursing visits scheduled 4 weeks after discharge. These visits allow nursing staff to dress and flush these catheters for routine maintenance per institutional policy. The implementation of the discharge checklist note creates a mechanism of tracking performance in meeting this goal moving forward, whereas no method was in place to track this metric.

Discussion

The 2013 IOM report Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis found that that cancer care is not as patient-centered, accessible, coordinated, or evidence-based as it could be, with detrimental impacts on patients.3 The document offered a conceptual framework to improve quality of cancer care that includes the translation of evidence into clinical practice, quality measurement, and performance improvement, as well as using advances in information technology to enhance quality measurement and performance improvement. Our quality initiative uses this framework to work toward the goal as stated by the IOM report: to deliver “comprehensive, patient-centered, evidence-based, high-quality cancer care that is accessible and affordable.”3

Two large studies that evaluated risk factors for 15-day and 30-day hospital readmissions identified cancer diagnosis as a risk factor for increased hospital readmission, highlighting the need to identify strategies to improve the discharge process for these patients.4,5 Timely outpatient follow-up and better patient hand-off may improve clinical outcomes among this high-risk patient population after hospital discharge. Multiple studies have demonstrated that timely follow-up is associated with fewer readmissions.1,8-10 A study by Forster and colleagues that evaluated postdischarge adverse events (AEs) revealed a 23% incidence of AEs with 12% of these identified as preventable. Postdischarge monitoring was deemed inadequate among these patients, with closer follow-up and improved hand-offs between inpatient and outpatient medical teams identified as possible interventions to improve postdischarge patient monitoring and to prevent AEs.7

The present quality initiative to standardize the discharge process for the hematology and oncology service decreased time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, improved communication between inpatient and outpatient teams, and decreased process variation. Timelier follow-up for this complex patient population likely will prevent clinical decompensation, delays in treatment, and directly improve patient access to care.

The multidisciplinary nature of this effort was instrumental to successful completion. In a complex health care system, it is challenging to truly understand a problem and identify possible solutions without the perspective of all members of the care team. The involvement of team members with training in quality improvement methodology was important to evaluate and develop interventions in a systematic way. Furthermore, the support and involvement of leadership is important in order to allocate resources appropriately to achieve system changes that improve care. Using quality improvement methodology, the team was able to map our processes and perform gap and root cause analyses. Strategies were identified to improve our performance using a solutions approach. Changes were implemented with continued intermittent meetings for monitoring of progression and discussion of how interventions could be made more efficient, effective, and user friendly. The primary goal was ultimately achieved.

Integration of intervention into the EMR embodies the IOM’s call to use advances in information technology to enhance the quality and delivery of care, quality measurement, and performance improvement.3 This intervention offered the strongest system changes as an electronic clinical decision support tool was developed and embedded into the EMR in the form of a Discharge Checklist Note that is linked to associated orders. This intervention was the most robust, as it provided objective data regarding utilization of the checklist, offered a more efficient way to communicate with team members regarding discharge needs, and streamlined the workflow for the discharging provider. Furthermore, this electronic tool created the ability to measure other important aspects in the care of this patient population that we previously had no mechanism of measuring: timely nursing appointments for routine care of PICC lines and ports.

Limitations

The absence of clinical endpoints was a limitation of this study. The present study was unable to evaluate the effect of the intervention on readmission rates, emergency department visits, hospital length of stay, cost, or mortality. Coordinating this multidisciplinary effort required much time and planning, and additional resources were not available to evaluate these clinical endpoints. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether the increased patient access and closer follow-up would result in improvement in these clinical endpoints. Another consideration for future improvement projects would be to include patients in the multidisciplinary team. The patient perspective would be invaluable in identifying gaps in care delivery and strategies aimed at improving care delivery.

Conclusions

This quality initiative to standardize the discharge process for the hematology and oncology service decreased time to the initial hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, improved communication between inpatient and outpatient teams, and decreased process variation. Timelier follow-up for this complex patient population likely will prevent clinical decompensation, delays in treatment, and directly improve patient access to care.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patients for whom we hope our process improvement efforts will ultimately benefit. We thank all the hematology and oncology staff at Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital and Loyola University Medical Center residents and fellows who care for our patients and participated in the multidisciplinary team to improve care for our patients. We thank the following professionals for their uncompensated assistance in the coordination and execution of this initiative: Robert Kutter, MS, and Meghan O’Halloran, MD.

1. Jackson C, Shahsahebi M, Wedlake T, DuBard CA. Timeliness of outpatient follow-up: an evidence-based approach for planning after hospital discharge. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):115-122. doi:10.1370/afm.1753

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. Levit LA, Balogh E, Nass SJ, Ganz P, Institute of Medicine (U.S.), eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

4. Allaudeen N, Vidyarthi A, Maselli J, Auerbach A. Redefining readmission risk factors for general medicine patients. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):54-60. doi:10.1002/jhm.805

5. Dorajoo SR, See V, Chan CT, et al. Identifying potentially avoidable readmissions: a medication-based 15-day readmission risk stratification algorithm. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(3):268-277. doi:10.1002/phar.1896

6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.831

7. Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital [published correction appears in CMAJ. 2004 March 2;170(5):771]. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345-349.

8. Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716-1722. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.533

9. Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397. doi:10.1002/jhm.666

10. Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Outpatient follow-up visit and 30-day emergency department visit and readmission in patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1664-1670. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.345

Hematology and oncology patients are a complex patient population that requires timely follow-up to prevent clinical decompensation and delays in treatment. Previous reports have demonstrated that outpatient follow-up within 14 days is associated with decreased 30-day readmissions. The magnitude of this effect is greater for higher-risk patients.1 Therefore, patients being discharged from the hematology and oncology inpatient service should be seen by a hematology and oncology provider within 14 days of discharge. Patients who do not require close oncologic follow-up should be seen by a primary care provider (PCP) within this timeframe.

Background

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) identified the need to focus on quality improvement and patient safety with a 1999 report, To Err Is Human.2 Tremendous strides have been made in the areas of quality improvement and patient safety over the past 2 decades. In a 2013 report, the IOM further identified hematology and oncology care as an area of need due to a combination of growing demand, complexity of cancer and cancer treatment, shrinking workforce, and rising costs. The report concluded that cancer care is not as patient-centered, accessible, coordinated, or evidence based as it could be, with detrimental impacts on patients.3 Patients with cancer have been identified as a high-risk population for hospital readmissions.4,5 Lack of timely follow-up and failed hand-offs have been identified as factors contributing to poor outcomes at time of discharge.6-10

Upon internal review of baseline performance data, we identified areas needing improvement in the discharge process. These included time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, percent of patients with PCP appointments scheduled at time of discharge, and electronically alerts for the outpatient hematologist/oncologist to discharge summaries. It was determined that patients discharged from the inpatient service were seen a mean 17 days later by their outpatient hematology and oncology provider and the time to the follow-up appointment varied substantially, with some patients being seen several weeks to months after discharge. Furthermore, only 68% of patients had a primary care appointment scheduled at the time of discharge. These data along with review of data reported in the medical literature supported our initiative for improvement in the transition from inpatient to outpatient care for our hematology and oncology patients.

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement methodology was used to create and implement several interventions to standardize the discharge process for this patient population, with the primary goal of decreasing the mean time to hematology and oncology follow-up from 17 days by 12% to fewer than 14 days. Patients who do not require close oncologic follow-up should be seen by a PCP within this timeframe. Otherwise, PCP follow-up within at least 6 months should be made. Secondary aims included (1) an increase in scheduled PCP visits at time of discharge from 68% to > 90%; and (2) an increase in communication of the discharge summary via electronic alerting of the outpatient hematology and oncology physician from 20% to > 90%. Herein, we report our experience and results of this quality improvement initiative

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at Edward Hines Veteran Affairs Hospital in Hines, Illinois reviewed this single-center study and deemed it to be exempt from oversight. Using PDSA quality improvement methodology, a multidisciplinary team of hematology and oncology staff developed and implemented a standardized discharge process. The multidisciplinary team included a robust representation of inpatient and outpatient staff caring for the hematology and oncology patient population, including attending physicians, fellows, residents, advanced practice nurses, registered nurses, clinical pharmacists, patient care coordinators, clinic schedulers, clinical applications coordinators, quality support staff, and a systems redesign coach. Hospital leadership including chief of staff, chief of medicine, and chief of nursing participated as the management guidance team. Several interviews and group meetings were conducted and a multidisciplinary team collaboratively developed and implemented the interventions and monitored the results.

Outcome measures were identified, including time to hematology and oncology clinic visit, primary care follow-up scheduling, and communication of discharge to the outpatient hematology and oncology physician. Baseline data were collected and reviewed. The multidisciplinary team developed a process flow map to understand the steps and resources involved with the transition from inpatient to outpatient care. Gap analysis and root cause analysis were performed. A solutions approach was applied to develop interventions. Table 1 shows a summary of the identified problems, symptoms, associated causes, the interventions aimed to address the problems, and expected outcomes. Rotating resident physicians were trained through online and in-person education. The multidisciplinary team met intermittently to monitor outcomes, provide feedback, further refine interventions, and develop additional interventions.

PDSA Cycle 1

A standardized discharge process was developed in the form of guidelines and expectations. These include an explanation of unique features of the hematology and oncology service and expectations of medication reconciliation with emphasis placed on antiemetics, antimicrobial prophylaxis, and bowel regimen when appropriate, outpatient hematology and oncology follow-up within 14 days, primary care follow-up, communication with the outpatient hematology and oncology physician, written discharge instructions, and bedside teaching when appropriate.

PDSA Cycle 2

Based on team member feedback and further discussions, a discharge checklist was developed. This checklist was available online, reviewed in person, and posted in the team room for rotating residents to use for discharge planning and when discharging patients (Figure 1).

PDSA Cycle 3

Based on ongoing user feedback, group discussions, and data monitoring, the discharge checklist was further refined and updated. An electronic clinical decision support tool was developed and integrated into the electronic medical record (EMR) in the form of a discharge checklist note template directly linked to orders. The tool is a computerized patient record system (CPRS) note template that prompts users to select whether medications or return to clinic orders are needed and offers a menu of frequently used medications. If any of the selections are chosen within the note template, an order is generated automatically in the chart that requires only the user’s signature. Furthermore, the patient care coordinator reviews the prescribed follow-up and works with the medical support assistant to make these appointments. The physician is contacted only when an appointment cannot be made. Therefore, this tool allows many additional actions to be bypassed such as generating medication and return to clinic orders individually and calling schedulers to make follow-up appointments (Figure 2).

Data Analysis

All patients discharged during the 2-month period prior to and discharged after the implementation of the standardized process were reviewed. Patients who followed up with hematology and oncology at another facility, enrolled in hospice, or died during admission were excluded. Follow-up appointment scheduling data and communication between inpatient and outpatient providers were reviewed. Data were analyzed using XmR statistical process control chart and Fisher’s Exact Test using GraphPad. Control limits were calculated for each PDSA cycle as the mean ± the average of the moving range multiplied by 2.66. All data were included in the analysis.

Results

A total of 142 consecutive patients were reviewed from May 1, 2018 to August 31, 2018 and January 1, 2019 to April 30, 2019, including 58 patients prior to the intervention and 84 patients during PDSA cycles. There was a gap in data collection between September 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018 due to limited team member availability. All data were collected by 2 reviewers—a postgraduate year (PGY)-4 chief resident and a PGY-2 internal medicine resident. The median age of patients in the preintervention group was 72 years and 69 years in the postintervention group. All patients were men. Baseline data revealed a mean 17 days to hematology and oncology follow-up. Primary care visits were scheduled for 68% of patients at the time of discharge. The outpatient hematology and oncology physician was alerted electronically to the discharge summary for 20% of the patients (Table 2).

The primary endpoint of time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment improved to 13 days in PDSA cycles 1 and 2 and 10 days in PDSA cycle 3. The target of mean 14 days to follow-up was achieved. The statistical process control chart shows 5 shifts with clusters of ≥ 7 points below the mean revealing a true signal or change in the data and demonstrating that an improvement was seen (Figure 3). Furthermore, the statistical process control chart demonstrates upper control limit decreased from 58 days at baseline to 21 days in PDSA cycle 3, suggesting a decrease in variation.

Regarding secondary endpoints, the outpatient hematology and oncology attending physician and/or fellow was alerted electronically to the discharge summary for 62% of patients compared with 20% at baseline (P = .01), and primary care appointments were scheduled for 77% of patients after the intervention compared with 68% at baseline (P = .88) (Table 2).

Through ongoing meetings, discussions, and feedback, we identified additional objectives unique to this patient population that had no performance measurement. These included peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) care nursing visits scheduled 1 week after discharge and port care nursing visits scheduled 4 weeks after discharge. These visits allow nursing staff to dress and flush these catheters for routine maintenance per institutional policy. The implementation of the discharge checklist note creates a mechanism of tracking performance in meeting this goal moving forward, whereas no method was in place to track this metric.

Discussion

The 2013 IOM report Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis found that that cancer care is not as patient-centered, accessible, coordinated, or evidence-based as it could be, with detrimental impacts on patients.3 The document offered a conceptual framework to improve quality of cancer care that includes the translation of evidence into clinical practice, quality measurement, and performance improvement, as well as using advances in information technology to enhance quality measurement and performance improvement. Our quality initiative uses this framework to work toward the goal as stated by the IOM report: to deliver “comprehensive, patient-centered, evidence-based, high-quality cancer care that is accessible and affordable.”3

Two large studies that evaluated risk factors for 15-day and 30-day hospital readmissions identified cancer diagnosis as a risk factor for increased hospital readmission, highlighting the need to identify strategies to improve the discharge process for these patients.4,5 Timely outpatient follow-up and better patient hand-off may improve clinical outcomes among this high-risk patient population after hospital discharge. Multiple studies have demonstrated that timely follow-up is associated with fewer readmissions.1,8-10 A study by Forster and colleagues that evaluated postdischarge adverse events (AEs) revealed a 23% incidence of AEs with 12% of these identified as preventable. Postdischarge monitoring was deemed inadequate among these patients, with closer follow-up and improved hand-offs between inpatient and outpatient medical teams identified as possible interventions to improve postdischarge patient monitoring and to prevent AEs.7

The present quality initiative to standardize the discharge process for the hematology and oncology service decreased time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, improved communication between inpatient and outpatient teams, and decreased process variation. Timelier follow-up for this complex patient population likely will prevent clinical decompensation, delays in treatment, and directly improve patient access to care.

The multidisciplinary nature of this effort was instrumental to successful completion. In a complex health care system, it is challenging to truly understand a problem and identify possible solutions without the perspective of all members of the care team. The involvement of team members with training in quality improvement methodology was important to evaluate and develop interventions in a systematic way. Furthermore, the support and involvement of leadership is important in order to allocate resources appropriately to achieve system changes that improve care. Using quality improvement methodology, the team was able to map our processes and perform gap and root cause analyses. Strategies were identified to improve our performance using a solutions approach. Changes were implemented with continued intermittent meetings for monitoring of progression and discussion of how interventions could be made more efficient, effective, and user friendly. The primary goal was ultimately achieved.

Integration of intervention into the EMR embodies the IOM’s call to use advances in information technology to enhance the quality and delivery of care, quality measurement, and performance improvement.3 This intervention offered the strongest system changes as an electronic clinical decision support tool was developed and embedded into the EMR in the form of a Discharge Checklist Note that is linked to associated orders. This intervention was the most robust, as it provided objective data regarding utilization of the checklist, offered a more efficient way to communicate with team members regarding discharge needs, and streamlined the workflow for the discharging provider. Furthermore, this electronic tool created the ability to measure other important aspects in the care of this patient population that we previously had no mechanism of measuring: timely nursing appointments for routine care of PICC lines and ports.

Limitations

The absence of clinical endpoints was a limitation of this study. The present study was unable to evaluate the effect of the intervention on readmission rates, emergency department visits, hospital length of stay, cost, or mortality. Coordinating this multidisciplinary effort required much time and planning, and additional resources were not available to evaluate these clinical endpoints. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether the increased patient access and closer follow-up would result in improvement in these clinical endpoints. Another consideration for future improvement projects would be to include patients in the multidisciplinary team. The patient perspective would be invaluable in identifying gaps in care delivery and strategies aimed at improving care delivery.

Conclusions

This quality initiative to standardize the discharge process for the hematology and oncology service decreased time to the initial hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, improved communication between inpatient and outpatient teams, and decreased process variation. Timelier follow-up for this complex patient population likely will prevent clinical decompensation, delays in treatment, and directly improve patient access to care.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patients for whom we hope our process improvement efforts will ultimately benefit. We thank all the hematology and oncology staff at Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital and Loyola University Medical Center residents and fellows who care for our patients and participated in the multidisciplinary team to improve care for our patients. We thank the following professionals for their uncompensated assistance in the coordination and execution of this initiative: Robert Kutter, MS, and Meghan O’Halloran, MD.

Hematology and oncology patients are a complex patient population that requires timely follow-up to prevent clinical decompensation and delays in treatment. Previous reports have demonstrated that outpatient follow-up within 14 days is associated with decreased 30-day readmissions. The magnitude of this effect is greater for higher-risk patients.1 Therefore, patients being discharged from the hematology and oncology inpatient service should be seen by a hematology and oncology provider within 14 days of discharge. Patients who do not require close oncologic follow-up should be seen by a primary care provider (PCP) within this timeframe.

Background

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) identified the need to focus on quality improvement and patient safety with a 1999 report, To Err Is Human.2 Tremendous strides have been made in the areas of quality improvement and patient safety over the past 2 decades. In a 2013 report, the IOM further identified hematology and oncology care as an area of need due to a combination of growing demand, complexity of cancer and cancer treatment, shrinking workforce, and rising costs. The report concluded that cancer care is not as patient-centered, accessible, coordinated, or evidence based as it could be, with detrimental impacts on patients.3 Patients with cancer have been identified as a high-risk population for hospital readmissions.4,5 Lack of timely follow-up and failed hand-offs have been identified as factors contributing to poor outcomes at time of discharge.6-10

Upon internal review of baseline performance data, we identified areas needing improvement in the discharge process. These included time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, percent of patients with PCP appointments scheduled at time of discharge, and electronically alerts for the outpatient hematologist/oncologist to discharge summaries. It was determined that patients discharged from the inpatient service were seen a mean 17 days later by their outpatient hematology and oncology provider and the time to the follow-up appointment varied substantially, with some patients being seen several weeks to months after discharge. Furthermore, only 68% of patients had a primary care appointment scheduled at the time of discharge. These data along with review of data reported in the medical literature supported our initiative for improvement in the transition from inpatient to outpatient care for our hematology and oncology patients.

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement methodology was used to create and implement several interventions to standardize the discharge process for this patient population, with the primary goal of decreasing the mean time to hematology and oncology follow-up from 17 days by 12% to fewer than 14 days. Patients who do not require close oncologic follow-up should be seen by a PCP within this timeframe. Otherwise, PCP follow-up within at least 6 months should be made. Secondary aims included (1) an increase in scheduled PCP visits at time of discharge from 68% to > 90%; and (2) an increase in communication of the discharge summary via electronic alerting of the outpatient hematology and oncology physician from 20% to > 90%. Herein, we report our experience and results of this quality improvement initiative

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at Edward Hines Veteran Affairs Hospital in Hines, Illinois reviewed this single-center study and deemed it to be exempt from oversight. Using PDSA quality improvement methodology, a multidisciplinary team of hematology and oncology staff developed and implemented a standardized discharge process. The multidisciplinary team included a robust representation of inpatient and outpatient staff caring for the hematology and oncology patient population, including attending physicians, fellows, residents, advanced practice nurses, registered nurses, clinical pharmacists, patient care coordinators, clinic schedulers, clinical applications coordinators, quality support staff, and a systems redesign coach. Hospital leadership including chief of staff, chief of medicine, and chief of nursing participated as the management guidance team. Several interviews and group meetings were conducted and a multidisciplinary team collaboratively developed and implemented the interventions and monitored the results.

Outcome measures were identified, including time to hematology and oncology clinic visit, primary care follow-up scheduling, and communication of discharge to the outpatient hematology and oncology physician. Baseline data were collected and reviewed. The multidisciplinary team developed a process flow map to understand the steps and resources involved with the transition from inpatient to outpatient care. Gap analysis and root cause analysis were performed. A solutions approach was applied to develop interventions. Table 1 shows a summary of the identified problems, symptoms, associated causes, the interventions aimed to address the problems, and expected outcomes. Rotating resident physicians were trained through online and in-person education. The multidisciplinary team met intermittently to monitor outcomes, provide feedback, further refine interventions, and develop additional interventions.

PDSA Cycle 1

A standardized discharge process was developed in the form of guidelines and expectations. These include an explanation of unique features of the hematology and oncology service and expectations of medication reconciliation with emphasis placed on antiemetics, antimicrobial prophylaxis, and bowel regimen when appropriate, outpatient hematology and oncology follow-up within 14 days, primary care follow-up, communication with the outpatient hematology and oncology physician, written discharge instructions, and bedside teaching when appropriate.

PDSA Cycle 2

Based on team member feedback and further discussions, a discharge checklist was developed. This checklist was available online, reviewed in person, and posted in the team room for rotating residents to use for discharge planning and when discharging patients (Figure 1).

PDSA Cycle 3

Based on ongoing user feedback, group discussions, and data monitoring, the discharge checklist was further refined and updated. An electronic clinical decision support tool was developed and integrated into the electronic medical record (EMR) in the form of a discharge checklist note template directly linked to orders. The tool is a computerized patient record system (CPRS) note template that prompts users to select whether medications or return to clinic orders are needed and offers a menu of frequently used medications. If any of the selections are chosen within the note template, an order is generated automatically in the chart that requires only the user’s signature. Furthermore, the patient care coordinator reviews the prescribed follow-up and works with the medical support assistant to make these appointments. The physician is contacted only when an appointment cannot be made. Therefore, this tool allows many additional actions to be bypassed such as generating medication and return to clinic orders individually and calling schedulers to make follow-up appointments (Figure 2).

Data Analysis

All patients discharged during the 2-month period prior to and discharged after the implementation of the standardized process were reviewed. Patients who followed up with hematology and oncology at another facility, enrolled in hospice, or died during admission were excluded. Follow-up appointment scheduling data and communication between inpatient and outpatient providers were reviewed. Data were analyzed using XmR statistical process control chart and Fisher’s Exact Test using GraphPad. Control limits were calculated for each PDSA cycle as the mean ± the average of the moving range multiplied by 2.66. All data were included in the analysis.

Results

A total of 142 consecutive patients were reviewed from May 1, 2018 to August 31, 2018 and January 1, 2019 to April 30, 2019, including 58 patients prior to the intervention and 84 patients during PDSA cycles. There was a gap in data collection between September 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018 due to limited team member availability. All data were collected by 2 reviewers—a postgraduate year (PGY)-4 chief resident and a PGY-2 internal medicine resident. The median age of patients in the preintervention group was 72 years and 69 years in the postintervention group. All patients were men. Baseline data revealed a mean 17 days to hematology and oncology follow-up. Primary care visits were scheduled for 68% of patients at the time of discharge. The outpatient hematology and oncology physician was alerted electronically to the discharge summary for 20% of the patients (Table 2).

The primary endpoint of time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment improved to 13 days in PDSA cycles 1 and 2 and 10 days in PDSA cycle 3. The target of mean 14 days to follow-up was achieved. The statistical process control chart shows 5 shifts with clusters of ≥ 7 points below the mean revealing a true signal or change in the data and demonstrating that an improvement was seen (Figure 3). Furthermore, the statistical process control chart demonstrates upper control limit decreased from 58 days at baseline to 21 days in PDSA cycle 3, suggesting a decrease in variation.

Regarding secondary endpoints, the outpatient hematology and oncology attending physician and/or fellow was alerted electronically to the discharge summary for 62% of patients compared with 20% at baseline (P = .01), and primary care appointments were scheduled for 77% of patients after the intervention compared with 68% at baseline (P = .88) (Table 2).

Through ongoing meetings, discussions, and feedback, we identified additional objectives unique to this patient population that had no performance measurement. These included peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) care nursing visits scheduled 1 week after discharge and port care nursing visits scheduled 4 weeks after discharge. These visits allow nursing staff to dress and flush these catheters for routine maintenance per institutional policy. The implementation of the discharge checklist note creates a mechanism of tracking performance in meeting this goal moving forward, whereas no method was in place to track this metric.

Discussion

The 2013 IOM report Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis found that that cancer care is not as patient-centered, accessible, coordinated, or evidence-based as it could be, with detrimental impacts on patients.3 The document offered a conceptual framework to improve quality of cancer care that includes the translation of evidence into clinical practice, quality measurement, and performance improvement, as well as using advances in information technology to enhance quality measurement and performance improvement. Our quality initiative uses this framework to work toward the goal as stated by the IOM report: to deliver “comprehensive, patient-centered, evidence-based, high-quality cancer care that is accessible and affordable.”3

Two large studies that evaluated risk factors for 15-day and 30-day hospital readmissions identified cancer diagnosis as a risk factor for increased hospital readmission, highlighting the need to identify strategies to improve the discharge process for these patients.4,5 Timely outpatient follow-up and better patient hand-off may improve clinical outcomes among this high-risk patient population after hospital discharge. Multiple studies have demonstrated that timely follow-up is associated with fewer readmissions.1,8-10 A study by Forster and colleagues that evaluated postdischarge adverse events (AEs) revealed a 23% incidence of AEs with 12% of these identified as preventable. Postdischarge monitoring was deemed inadequate among these patients, with closer follow-up and improved hand-offs between inpatient and outpatient medical teams identified as possible interventions to improve postdischarge patient monitoring and to prevent AEs.7

The present quality initiative to standardize the discharge process for the hematology and oncology service decreased time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, improved communication between inpatient and outpatient teams, and decreased process variation. Timelier follow-up for this complex patient population likely will prevent clinical decompensation, delays in treatment, and directly improve patient access to care.

The multidisciplinary nature of this effort was instrumental to successful completion. In a complex health care system, it is challenging to truly understand a problem and identify possible solutions without the perspective of all members of the care team. The involvement of team members with training in quality improvement methodology was important to evaluate and develop interventions in a systematic way. Furthermore, the support and involvement of leadership is important in order to allocate resources appropriately to achieve system changes that improve care. Using quality improvement methodology, the team was able to map our processes and perform gap and root cause analyses. Strategies were identified to improve our performance using a solutions approach. Changes were implemented with continued intermittent meetings for monitoring of progression and discussion of how interventions could be made more efficient, effective, and user friendly. The primary goal was ultimately achieved.

Integration of intervention into the EMR embodies the IOM’s call to use advances in information technology to enhance the quality and delivery of care, quality measurement, and performance improvement.3 This intervention offered the strongest system changes as an electronic clinical decision support tool was developed and embedded into the EMR in the form of a Discharge Checklist Note that is linked to associated orders. This intervention was the most robust, as it provided objective data regarding utilization of the checklist, offered a more efficient way to communicate with team members regarding discharge needs, and streamlined the workflow for the discharging provider. Furthermore, this electronic tool created the ability to measure other important aspects in the care of this patient population that we previously had no mechanism of measuring: timely nursing appointments for routine care of PICC lines and ports.

Limitations

The absence of clinical endpoints was a limitation of this study. The present study was unable to evaluate the effect of the intervention on readmission rates, emergency department visits, hospital length of stay, cost, or mortality. Coordinating this multidisciplinary effort required much time and planning, and additional resources were not available to evaluate these clinical endpoints. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether the increased patient access and closer follow-up would result in improvement in these clinical endpoints. Another consideration for future improvement projects would be to include patients in the multidisciplinary team. The patient perspective would be invaluable in identifying gaps in care delivery and strategies aimed at improving care delivery.

Conclusions

This quality initiative to standardize the discharge process for the hematology and oncology service decreased time to the initial hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, improved communication between inpatient and outpatient teams, and decreased process variation. Timelier follow-up for this complex patient population likely will prevent clinical decompensation, delays in treatment, and directly improve patient access to care.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patients for whom we hope our process improvement efforts will ultimately benefit. We thank all the hematology and oncology staff at Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital and Loyola University Medical Center residents and fellows who care for our patients and participated in the multidisciplinary team to improve care for our patients. We thank the following professionals for their uncompensated assistance in the coordination and execution of this initiative: Robert Kutter, MS, and Meghan O’Halloran, MD.

1. Jackson C, Shahsahebi M, Wedlake T, DuBard CA. Timeliness of outpatient follow-up: an evidence-based approach for planning after hospital discharge. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):115-122. doi:10.1370/afm.1753

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. Levit LA, Balogh E, Nass SJ, Ganz P, Institute of Medicine (U.S.), eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

4. Allaudeen N, Vidyarthi A, Maselli J, Auerbach A. Redefining readmission risk factors for general medicine patients. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):54-60. doi:10.1002/jhm.805

5. Dorajoo SR, See V, Chan CT, et al. Identifying potentially avoidable readmissions: a medication-based 15-day readmission risk stratification algorithm. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(3):268-277. doi:10.1002/phar.1896

6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.831

7. Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital [published correction appears in CMAJ. 2004 March 2;170(5):771]. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345-349.

8. Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716-1722. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.533

9. Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397. doi:10.1002/jhm.666

10. Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Outpatient follow-up visit and 30-day emergency department visit and readmission in patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1664-1670. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.345

1. Jackson C, Shahsahebi M, Wedlake T, DuBard CA. Timeliness of outpatient follow-up: an evidence-based approach for planning after hospital discharge. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):115-122. doi:10.1370/afm.1753

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

3. Levit LA, Balogh E, Nass SJ, Ganz P, Institute of Medicine (U.S.), eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

4. Allaudeen N, Vidyarthi A, Maselli J, Auerbach A. Redefining readmission risk factors for general medicine patients. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):54-60. doi:10.1002/jhm.805

5. Dorajoo SR, See V, Chan CT, et al. Identifying potentially avoidable readmissions: a medication-based 15-day readmission risk stratification algorithm. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(3):268-277. doi:10.1002/phar.1896

6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.831

7. Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital [published correction appears in CMAJ. 2004 March 2;170(5):771]. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345-349.

8. Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716-1722. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.533

9. Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397. doi:10.1002/jhm.666

10. Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Outpatient follow-up visit and 30-day emergency department visit and readmission in patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1664-1670. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.345