User login

A Rare Case of Segmental Neurofibromatosis With Multiple Blue-Red Pseudoatrophic Plaques

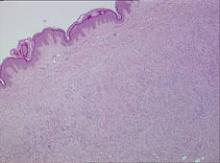

In the setting of neurofibromatosis (NF), neurofibromas commonly appear as flesh-colored nodular lesions.1 The presence of blue-red pseudoatrophic neurofibromas is rare, with only 1 known case of the segmental variant.2 Microscopic examination typically reveals thick-walled blood vessels in the papillary dermis and neurofibromatous tissue in the hypodermis. The neuroid proliferation is associated with the reduction of collagen tissue. This type of neurofibroma has an early presentation and it can be helpful in the diagnosis of some cases of NF.3,4

Case Report

A 5-year-old girl presented with 2 blue-red, well-demarcated, atrophic patches on the left leg. One plaque was localized on the left thigh, which had appeared at 7 months of age, and the other was on the left calf, which presented at 2 years of age (Figure 1). The lesions were 10- to 15-cm in diameter, roughly oval shaped, and completely asymptomatic. The skin overlying the atrophic patches showed a visible venous reticulum, and palpation revealed multiple nodular lesions. Physical examination revealed no cafè au lait spots, axillary freckling, Lisch nodules, or clinical signs of NF. Her family history was negative for NF. Physical and neurologic examinations revealed no abnormalities.

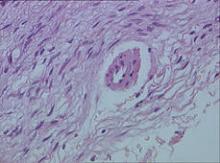

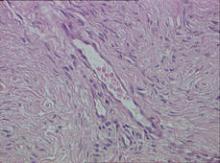

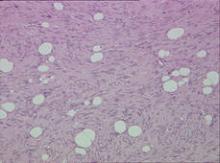

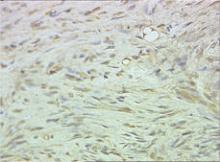

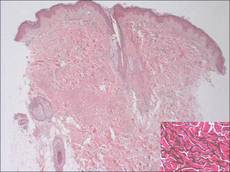

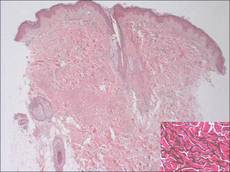

Biopsy specimens were obtained from 1 of the atrophic patches and from 1 of the nodules. Microscopic examination of the atrophic patch showed a dermal proliferation of spindle elements dispersed in loose connective tissue (Figure 2) and ectatic (Figure 3) or thick-walled (Figure 4) blood vessels. Microscopic exam-ination of the nodule disclosed a dermohypodermal neoplastic proliferation composed of monomorphic wavy nuclei cells intermingled with thin wavy collagen fibers (Figure 5). Immunohistochemicalstudy was positive for S-100 protein in the neuroid tissues (Figure 6) as well as epithelial membraneantigen and CD34; actin and CD68 were negative. Based on the histologic and clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with segmental NF characterized by blue-red pseudoatrophic plaques.

Comment

Segmental NF, a rare condition that is 10 to 20 times less frequent than NF type I, commonly presents with unilateral neurofibromas confined to a circumscribed body segment.2,5-7 The most common cutaneous marks in this rare disease are cafè au lait spots and axillary freckling, which typically are localized to the same anatomic region. In contrast to NF type I and II, systemic involvement and malignancies are uncommon in segmental NF.8-10 Cutaneous neurofibromas are benign tumors of the peripheral nerve that appear as soft, flesh-colored or slightly tan, sessile or polypoid papules or nodules that typically range in width from a few millimeters to several centimeters. These lesions typically appear after 10 years of age.

Other rare clinical types of neurofibromas include the plexiform, diffuse, and blue-red pseudoatrophic patches.3 In particular, the blue-red pseudoatrophic variant is considered a helpful clinical hallmark for the diagnosis of NF, especially due to its early onset in the disease course. It usually appears during the first months of life or can possibly be congenital.3,11

Neurofibromas classically present as well-circumscribed dermal nodules that consist of spindle-shaped cells and bundles of eosinophilic wavy fibrous tissue in the reticular dermis, which often also affect the subcutaneous tissue. Conversely, in the blue-red pseudoatrophic variant, tumor cells are associated with less connective tissue and with a reduction of collagen in the reticular dermis from diffuse replacement of neuroid tissue, even though there are no histologic signs of true atrophy.3 Furthermore, the blue-red color is most likely due to the vascular abnormalities, such as ectatic or thick-walled blood vessels overlying the subcutaneous fibromatous tissue.

We found different descriptions of this variant of neurofibroma in the literature with some clinical or histologic differences. The lesions are described as blue-red or cerulean macules, and on histology the angiomatous component is dominant.3,12 In other reports, the main clinical feature is skin atrophy. Lesions can be classified as pseudoatrophic plaques, dermal hypoplasia, or pseudoatrophic macules,3,4,11,13,14 which are different names for the same variant of blue-red pseudoatrophic neurofibromas.

Clinical studies on this neurofibroma refer to patients affected by NF type I; in 1 case the lesions appeared as segmental NF.14

Conclusion

Segmental NF is characterized by an unusual clinical onset of multiple and localized pseudoatrophic plaques in the absence of the common clinical features of NF. We recommend that pseudoatrophic patches undergo histologic examination for early diagnosis of rare cases of NF with such an unusual presentation.

1. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

2. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):864-869.

3. Westerhof W, Konrad K. Blue-red macules and pseudoatrophic macules: additional cutaneous signs in neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:577-581.

4. Piqué E, Olivares M, Fariña MC, et al. Pseudoatrophic macules: a variant of neurofibroma. Cutis. 1996;57:100-102.

5. Roth RR, Martines R, James WD. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:917-920.

6. Gonzalez G, Russi ME, Lodeiros A. Bilateral segmental neurofibromatosis: a case report and review. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:51-53.

7. Redlick FP, Shaw J. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

8. Friedman DP. Segmental neurofibromatosis (NF-5): a rare form of neurofibromatosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:971-972.

9. Dang JD, Cohen PR. Segmental neurofibromatosis and malignancy. Skinmed. 2010;8:156-159.

10. Mansur AT, Göktay F, Akkaya AD, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis: report of 3 cases. Cutis. 2011;87:45-50.

11. Kwon KS, Seo KH, Jang HS, et al. A case of congenital reddish neurofibromatous dermal hypoplasia. Cutis. 2001;68:253-256.

12. Vabres P, de Lonlay P, Amiel J, et al. Angiomatous and cerulodermic macules: early cutaneous signs of neurofibromatosis type I [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1998;125:593-594.

13. Misago N, Narisawa Y. Localized multiple pseudoatrophic plaques: a rare clinical form of segmental neurofibromatosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:522-523.

14. Norris JF, Smith AG, Fletcher PJ, et al. Neurofibromatous dermal hypoplasia: a clinical, pharmacological and ultrastructural study. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:435-441.

In the setting of neurofibromatosis (NF), neurofibromas commonly appear as flesh-colored nodular lesions.1 The presence of blue-red pseudoatrophic neurofibromas is rare, with only 1 known case of the segmental variant.2 Microscopic examination typically reveals thick-walled blood vessels in the papillary dermis and neurofibromatous tissue in the hypodermis. The neuroid proliferation is associated with the reduction of collagen tissue. This type of neurofibroma has an early presentation and it can be helpful in the diagnosis of some cases of NF.3,4

Case Report

A 5-year-old girl presented with 2 blue-red, well-demarcated, atrophic patches on the left leg. One plaque was localized on the left thigh, which had appeared at 7 months of age, and the other was on the left calf, which presented at 2 years of age (Figure 1). The lesions were 10- to 15-cm in diameter, roughly oval shaped, and completely asymptomatic. The skin overlying the atrophic patches showed a visible venous reticulum, and palpation revealed multiple nodular lesions. Physical examination revealed no cafè au lait spots, axillary freckling, Lisch nodules, or clinical signs of NF. Her family history was negative for NF. Physical and neurologic examinations revealed no abnormalities.

Biopsy specimens were obtained from 1 of the atrophic patches and from 1 of the nodules. Microscopic examination of the atrophic patch showed a dermal proliferation of spindle elements dispersed in loose connective tissue (Figure 2) and ectatic (Figure 3) or thick-walled (Figure 4) blood vessels. Microscopic exam-ination of the nodule disclosed a dermohypodermal neoplastic proliferation composed of monomorphic wavy nuclei cells intermingled with thin wavy collagen fibers (Figure 5). Immunohistochemicalstudy was positive for S-100 protein in the neuroid tissues (Figure 6) as well as epithelial membraneantigen and CD34; actin and CD68 were negative. Based on the histologic and clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with segmental NF characterized by blue-red pseudoatrophic plaques.

Comment

Segmental NF, a rare condition that is 10 to 20 times less frequent than NF type I, commonly presents with unilateral neurofibromas confined to a circumscribed body segment.2,5-7 The most common cutaneous marks in this rare disease are cafè au lait spots and axillary freckling, which typically are localized to the same anatomic region. In contrast to NF type I and II, systemic involvement and malignancies are uncommon in segmental NF.8-10 Cutaneous neurofibromas are benign tumors of the peripheral nerve that appear as soft, flesh-colored or slightly tan, sessile or polypoid papules or nodules that typically range in width from a few millimeters to several centimeters. These lesions typically appear after 10 years of age.

Other rare clinical types of neurofibromas include the plexiform, diffuse, and blue-red pseudoatrophic patches.3 In particular, the blue-red pseudoatrophic variant is considered a helpful clinical hallmark for the diagnosis of NF, especially due to its early onset in the disease course. It usually appears during the first months of life or can possibly be congenital.3,11

Neurofibromas classically present as well-circumscribed dermal nodules that consist of spindle-shaped cells and bundles of eosinophilic wavy fibrous tissue in the reticular dermis, which often also affect the subcutaneous tissue. Conversely, in the blue-red pseudoatrophic variant, tumor cells are associated with less connective tissue and with a reduction of collagen in the reticular dermis from diffuse replacement of neuroid tissue, even though there are no histologic signs of true atrophy.3 Furthermore, the blue-red color is most likely due to the vascular abnormalities, such as ectatic or thick-walled blood vessels overlying the subcutaneous fibromatous tissue.

We found different descriptions of this variant of neurofibroma in the literature with some clinical or histologic differences. The lesions are described as blue-red or cerulean macules, and on histology the angiomatous component is dominant.3,12 In other reports, the main clinical feature is skin atrophy. Lesions can be classified as pseudoatrophic plaques, dermal hypoplasia, or pseudoatrophic macules,3,4,11,13,14 which are different names for the same variant of blue-red pseudoatrophic neurofibromas.

Clinical studies on this neurofibroma refer to patients affected by NF type I; in 1 case the lesions appeared as segmental NF.14

Conclusion

Segmental NF is characterized by an unusual clinical onset of multiple and localized pseudoatrophic plaques in the absence of the common clinical features of NF. We recommend that pseudoatrophic patches undergo histologic examination for early diagnosis of rare cases of NF with such an unusual presentation.

In the setting of neurofibromatosis (NF), neurofibromas commonly appear as flesh-colored nodular lesions.1 The presence of blue-red pseudoatrophic neurofibromas is rare, with only 1 known case of the segmental variant.2 Microscopic examination typically reveals thick-walled blood vessels in the papillary dermis and neurofibromatous tissue in the hypodermis. The neuroid proliferation is associated with the reduction of collagen tissue. This type of neurofibroma has an early presentation and it can be helpful in the diagnosis of some cases of NF.3,4

Case Report

A 5-year-old girl presented with 2 blue-red, well-demarcated, atrophic patches on the left leg. One plaque was localized on the left thigh, which had appeared at 7 months of age, and the other was on the left calf, which presented at 2 years of age (Figure 1). The lesions were 10- to 15-cm in diameter, roughly oval shaped, and completely asymptomatic. The skin overlying the atrophic patches showed a visible venous reticulum, and palpation revealed multiple nodular lesions. Physical examination revealed no cafè au lait spots, axillary freckling, Lisch nodules, or clinical signs of NF. Her family history was negative for NF. Physical and neurologic examinations revealed no abnormalities.

Biopsy specimens were obtained from 1 of the atrophic patches and from 1 of the nodules. Microscopic examination of the atrophic patch showed a dermal proliferation of spindle elements dispersed in loose connective tissue (Figure 2) and ectatic (Figure 3) or thick-walled (Figure 4) blood vessels. Microscopic exam-ination of the nodule disclosed a dermohypodermal neoplastic proliferation composed of monomorphic wavy nuclei cells intermingled with thin wavy collagen fibers (Figure 5). Immunohistochemicalstudy was positive for S-100 protein in the neuroid tissues (Figure 6) as well as epithelial membraneantigen and CD34; actin and CD68 were negative. Based on the histologic and clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with segmental NF characterized by blue-red pseudoatrophic plaques.

Comment

Segmental NF, a rare condition that is 10 to 20 times less frequent than NF type I, commonly presents with unilateral neurofibromas confined to a circumscribed body segment.2,5-7 The most common cutaneous marks in this rare disease are cafè au lait spots and axillary freckling, which typically are localized to the same anatomic region. In contrast to NF type I and II, systemic involvement and malignancies are uncommon in segmental NF.8-10 Cutaneous neurofibromas are benign tumors of the peripheral nerve that appear as soft, flesh-colored or slightly tan, sessile or polypoid papules or nodules that typically range in width from a few millimeters to several centimeters. These lesions typically appear after 10 years of age.

Other rare clinical types of neurofibromas include the plexiform, diffuse, and blue-red pseudoatrophic patches.3 In particular, the blue-red pseudoatrophic variant is considered a helpful clinical hallmark for the diagnosis of NF, especially due to its early onset in the disease course. It usually appears during the first months of life or can possibly be congenital.3,11

Neurofibromas classically present as well-circumscribed dermal nodules that consist of spindle-shaped cells and bundles of eosinophilic wavy fibrous tissue in the reticular dermis, which often also affect the subcutaneous tissue. Conversely, in the blue-red pseudoatrophic variant, tumor cells are associated with less connective tissue and with a reduction of collagen in the reticular dermis from diffuse replacement of neuroid tissue, even though there are no histologic signs of true atrophy.3 Furthermore, the blue-red color is most likely due to the vascular abnormalities, such as ectatic or thick-walled blood vessels overlying the subcutaneous fibromatous tissue.

We found different descriptions of this variant of neurofibroma in the literature with some clinical or histologic differences. The lesions are described as blue-red or cerulean macules, and on histology the angiomatous component is dominant.3,12 In other reports, the main clinical feature is skin atrophy. Lesions can be classified as pseudoatrophic plaques, dermal hypoplasia, or pseudoatrophic macules,3,4,11,13,14 which are different names for the same variant of blue-red pseudoatrophic neurofibromas.

Clinical studies on this neurofibroma refer to patients affected by NF type I; in 1 case the lesions appeared as segmental NF.14

Conclusion

Segmental NF is characterized by an unusual clinical onset of multiple and localized pseudoatrophic plaques in the absence of the common clinical features of NF. We recommend that pseudoatrophic patches undergo histologic examination for early diagnosis of rare cases of NF with such an unusual presentation.

1. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

2. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):864-869.

3. Westerhof W, Konrad K. Blue-red macules and pseudoatrophic macules: additional cutaneous signs in neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:577-581.

4. Piqué E, Olivares M, Fariña MC, et al. Pseudoatrophic macules: a variant of neurofibroma. Cutis. 1996;57:100-102.

5. Roth RR, Martines R, James WD. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:917-920.

6. Gonzalez G, Russi ME, Lodeiros A. Bilateral segmental neurofibromatosis: a case report and review. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:51-53.

7. Redlick FP, Shaw J. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

8. Friedman DP. Segmental neurofibromatosis (NF-5): a rare form of neurofibromatosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:971-972.

9. Dang JD, Cohen PR. Segmental neurofibromatosis and malignancy. Skinmed. 2010;8:156-159.

10. Mansur AT, Göktay F, Akkaya AD, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis: report of 3 cases. Cutis. 2011;87:45-50.

11. Kwon KS, Seo KH, Jang HS, et al. A case of congenital reddish neurofibromatous dermal hypoplasia. Cutis. 2001;68:253-256.

12. Vabres P, de Lonlay P, Amiel J, et al. Angiomatous and cerulodermic macules: early cutaneous signs of neurofibromatosis type I [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1998;125:593-594.

13. Misago N, Narisawa Y. Localized multiple pseudoatrophic plaques: a rare clinical form of segmental neurofibromatosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:522-523.

14. Norris JF, Smith AG, Fletcher PJ, et al. Neurofibromatous dermal hypoplasia: a clinical, pharmacological and ultrastructural study. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:435-441.

1. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

2. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):864-869.

3. Westerhof W, Konrad K. Blue-red macules and pseudoatrophic macules: additional cutaneous signs in neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:577-581.

4. Piqué E, Olivares M, Fariña MC, et al. Pseudoatrophic macules: a variant of neurofibroma. Cutis. 1996;57:100-102.

5. Roth RR, Martines R, James WD. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:917-920.

6. Gonzalez G, Russi ME, Lodeiros A. Bilateral segmental neurofibromatosis: a case report and review. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:51-53.

7. Redlick FP, Shaw J. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

8. Friedman DP. Segmental neurofibromatosis (NF-5): a rare form of neurofibromatosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:971-972.

9. Dang JD, Cohen PR. Segmental neurofibromatosis and malignancy. Skinmed. 2010;8:156-159.

10. Mansur AT, Göktay F, Akkaya AD, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis: report of 3 cases. Cutis. 2011;87:45-50.

11. Kwon KS, Seo KH, Jang HS, et al. A case of congenital reddish neurofibromatous dermal hypoplasia. Cutis. 2001;68:253-256.

12. Vabres P, de Lonlay P, Amiel J, et al. Angiomatous and cerulodermic macules: early cutaneous signs of neurofibromatosis type I [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1998;125:593-594.

13. Misago N, Narisawa Y. Localized multiple pseudoatrophic plaques: a rare clinical form of segmental neurofibromatosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:522-523.

14. Norris JF, Smith AG, Fletcher PJ, et al. Neurofibromatous dermal hypoplasia: a clinical, pharmacological and ultrastructural study. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:435-441.

- Biopsy should be considered for pseudoatrophic patches to perform early diagnosis of neurofibroma-tosis (NF), which is rare.

- Blue-red or cerulean macules, especially if associated with skin atrophy, are highly suggestive of neurofibroma in a patient affected by NF.

Buschke-Ollendorff Syndrome: Sparing Unnecessary Investigations

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome (BOS) is a rare disease that is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with high penetrance. It is characterized by osteopoikilosis associated with skin manifestations. The approximate incidence of the disease is 1:20,000, with few cases reported in the literature since 1928.1 Skeletal lesions known as osteopoikilosis are areas of increased bone density that can be seen on radiographic imaging and typically are located in the substantia spongiosa of the epiphyses and metaphyses of long bones and the pelvis. In BOS, cutaneous lesions consist of elastic or collagen nevi. Phenotypic expression of the disease is variable, and skeletal and cutaneous lesions may occur separately. Gene mutations of proteins involved in bone and connective tissue morphogenesis have been described in patients with BOS.2-5

Case Reports

Patient 1

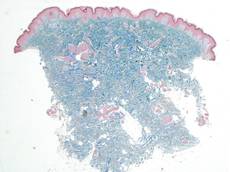

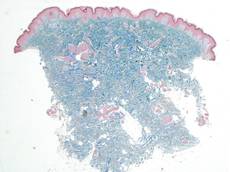

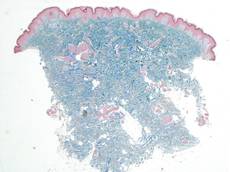

A 17-year-old adolescent girl was referred to our hospital for evaluation of an incidental finding of osteopoikilosis that had been noted in the setting of a traumatic event. Clinical examination revealed cutaneous lesions characterized by asymptomatic, linear, stringlike and atrophic fibrotic plaques localized symmetrically on the trunk, right buttock, and right thigh (Figure 1). The lesions on the thigh were present at birth and had spread progressively to the other areas. There was no known history of inflammatory skin disease to explain the presence of the lesions, and no family history of similar signs or symptoms was reported. Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy of a plaque from the trunk revealed increased collagen bundles associated with thick interlacing elastic fibers. The epidermis did not show any specific histologic alterations. These histopathologic features were diagnostic of a connective tissue nevus (Figure 2).

|

Figure 1. An asymptomatic atrophic fibrotic plaque localized on the right thigh. |

|

Figure 2. Low-power view of a punch biopsy showing a normal epidermis. Collagen bundles of the dermis were thickened and somewhat homogenized, as highlighted by the Masson stain (original magnification ×2.5). |

|

Figure 3. Radiograph of the legs revealed numerous small, ovoid or round foci of sclerosis on the substantia spongiosa of the metaphyses and the epiphyses of the femur, tibia, and fibula on both sides of the body. |

|

Figure 4. Multiple asymptomatic flesh-colored papules with elastic consistency on the back that were characteristic of dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata. |

|

Figure 5. The epidermis and dermis appeared normal on histopathology; however, the elastic fibers were markedly increased in both size and number up to the deep dermis in the absence of degenerating changes (H&E, original magnification ×2.5; vascular endothelial growth factor, original magnification ×20 [inset in bottom right corner]). |

|

| Figure 6. A radiograph of the left hand revealed small sporadic areas of sclerosis in the substantia spongiosa on the heads of some phalanges (white arrows). |

Radiographic imaging of the hands and feet revealed numerous small, ovoid or round foci of sclerosis that were a few millimeters in diameter and were occasionally confluent. This finding was prevalent on the carpal and tarsal bones but less evident on the phalanges and the epiphysis of the metatarsal and metacarpal bones. Full radiographic imaging of both arms and legs subsequently was obtained and showed similar lesions predominantly in the substantia spongiosa of the metaphyses and the epiphyses of the humerus, femur, tibia, and fibula bilaterally (Figure 3). Evaluation of the patient’s parents revealed that her mother had sporadic lenticular areas of increased bone density seen on radiography of the carpal and tarsal bones, particularly at the level of calcaneus, and the proximal and distal humeral epiphyses.

These lesions in our patient were consistent with an incomplete form of osteopoikilosis, which reflects the known variable expression of BOS. The radiologic findings in addition to the cutaneous lesions and the positive family history supported a diagnosis of BOS.

Patient 2

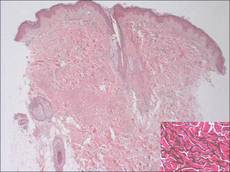

A 5-year-old boy presented with multiple congenital, asymptomatic, flesh-colored papules with elastic consistency on the left thigh, back, and pubic area that were characteristic of dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata (Figure 4). The patient’s 7-year-old sister had similar cutaneous lesions. The patient underwent a skin biopsy from the back that revealed thickening of collagen bundles in the dermis with an increase in elastic fibers (Figure 5). On radiographic imaging, small sporadic areas of sclerosis were noted in the substantia spongiosa of the lateral aspect of the humeral capitulum, the radial neck, the capitate, the head of the proximal phalanx of the fourth finger on the left hand, and the heads of the third and fifth middle phalanges on the left hand (Figure 6). Radiography revealed osteopoikilosis on both humeral heads in the patient’s mother. These findings in addition to the dermatologic and histopathologic features suggested a diagnosis of BOS.

Comment

In 1928, Buschke and Ollendorff1 first reported the association between osteopoikilosis and dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata, which showed autosomal-dominant inheritance. Skin and bone lesions can occur independently in different family members. Two different clinical cutaneous patterns are described in BOS.2-4 The first and most frequent form is characterized by yellowish nodules often grouped in plaques that are asymmetrically distributed, such as those seen in patient 1. The second form is known as dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata, which was seen in patient 2. Histologically, most lesions show normal collagen fibrils and an increased number of elastic fibers.

Osteopoikilosis, also known as spotted bone disease or osteopathia condensans, is a rare asymptomatic bone dysplasia of unknown etiology. It is characterized by an abnormality in the bone maturation process and often is found incidentally on radiologic examination, as seen in patient 1. Radiologic signs of osteopoikilosis consist of small, disseminated, well-circumscribed areas of increased radiodensity located in the epiphyses and metaphyses of long bones, as well as the pelvis, hands, and feet. These lesions, which typically are asymptomatic, could sometimes be associated with bone and/or joint pain but do not cause a predisposition to fractures. Documentation of these bone lesions by early adult life is important to avoid confusion with osteoblastic metastases on the skeleton.6

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome is characterized by a variable expression. Loss-of-function mutations of the LEMD3 gene have been described in association with this disorder.7 This gene encodes an inner nuclear protein membrane with a C-terminal domain that binds SMAD2 and SMAD3 and antagonizes the bone morphogenetic proteins and transforming growth factor b. These proteins are involved in connective tissue morphogenesis, inducing elastin production from fibroblasts.7 Seven novel loss-of-function mutations of LEMD3 have been identified.8 The segmental manifestation of BOS could be a consequence of the mosaicism resulting from a somatic mutation.9,10 A case describing the absence of LEMD3 mutation in an affected family suggested the genetic heterogeneity of BOS.11

Conclusion

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome is a benign condition with no repercussions on the patient’s health or quality of life. It does not require any specific treatment because the lesions generally remain asymptomatic and do not generate any substantial cosmetic burden. Mutation analysis was not performed in our patients because BOS has a good prognosis and the parents refused further investigation in both patients; therefore, a correct diagnosis was essential in our cases to rule out malignant bone disease in patient 1 whose osteopoikilosis prompted the workup and other disorders (eg, tuberous sclerosis, pseudoxanthoma elasticum) in patient 2 whose cutaneous lesions were the primary cause for presentation. A correct diagnosis of BOS is necessary to spare patients from expensive investigations and to provide reassurance about the benign nature of the disease.

1. Buschke A, Ollendorff H. Ein fall von dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata und osteopathia condensas disseminata. Derm Worchenschr. 1928;86:257-262.

2. Ramme K, Kolde G, Stadler R. Dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata with osteopoikilosis. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome [in German]. Hautarzt. 1993;44:312-314.

3. Schena D, Germi L, Zamperetti MR, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1159-1161.

4. Kawamura A, Ochiai T, Tan-Kinoshita M, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome: three generations in a Japanese family. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:133-137.

5. Woodrow SL, Pope FM, Handfield-Jones SE. The Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome presenting as familial elastic tissue naevi. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:890-893.

6. Whyte MP, Murphy WA, Siegel BA. 99mTc-pyrophosphate bone imaging in osteopoikilosis, osteopathia striata, and melorheostosis. Radiology. 1978;127:439-443.

7. Giro MG, Duvic M, Smith LT, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome associated with elevated elastin production by affected skin fibroblasts in culture. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:129-137.

8. Hellemans J, Preobrazhenska O, Willaert A, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in LEMD3 result in osteopoikilosis, Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome and melorheostosis [published online ahead of print October 17, 2004]. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1213-1218.

9. Ehrig T, Cockerell CJ. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome: report of a case and interpretation of the clinical phenotype as a type 2 segmental manifestation of an autosomal dominant skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1163-1166.

10. Hellemans J, Debeer P, Wright M, et al. Germline LEMD3 mutations are rare in sporadic patients with isolated melorheostosis. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:290.

11. Yadegari M, Whyte MP, Mumm S, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome: absence of LEMD3 mutation in an affected family. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:63-68.

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome (BOS) is a rare disease that is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with high penetrance. It is characterized by osteopoikilosis associated with skin manifestations. The approximate incidence of the disease is 1:20,000, with few cases reported in the literature since 1928.1 Skeletal lesions known as osteopoikilosis are areas of increased bone density that can be seen on radiographic imaging and typically are located in the substantia spongiosa of the epiphyses and metaphyses of long bones and the pelvis. In BOS, cutaneous lesions consist of elastic or collagen nevi. Phenotypic expression of the disease is variable, and skeletal and cutaneous lesions may occur separately. Gene mutations of proteins involved in bone and connective tissue morphogenesis have been described in patients with BOS.2-5

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 17-year-old adolescent girl was referred to our hospital for evaluation of an incidental finding of osteopoikilosis that had been noted in the setting of a traumatic event. Clinical examination revealed cutaneous lesions characterized by asymptomatic, linear, stringlike and atrophic fibrotic plaques localized symmetrically on the trunk, right buttock, and right thigh (Figure 1). The lesions on the thigh were present at birth and had spread progressively to the other areas. There was no known history of inflammatory skin disease to explain the presence of the lesions, and no family history of similar signs or symptoms was reported. Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy of a plaque from the trunk revealed increased collagen bundles associated with thick interlacing elastic fibers. The epidermis did not show any specific histologic alterations. These histopathologic features were diagnostic of a connective tissue nevus (Figure 2).

|

Figure 1. An asymptomatic atrophic fibrotic plaque localized on the right thigh. |

|

Figure 2. Low-power view of a punch biopsy showing a normal epidermis. Collagen bundles of the dermis were thickened and somewhat homogenized, as highlighted by the Masson stain (original magnification ×2.5). |

|

Figure 3. Radiograph of the legs revealed numerous small, ovoid or round foci of sclerosis on the substantia spongiosa of the metaphyses and the epiphyses of the femur, tibia, and fibula on both sides of the body. |

|

Figure 4. Multiple asymptomatic flesh-colored papules with elastic consistency on the back that were characteristic of dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata. |

|

Figure 5. The epidermis and dermis appeared normal on histopathology; however, the elastic fibers were markedly increased in both size and number up to the deep dermis in the absence of degenerating changes (H&E, original magnification ×2.5; vascular endothelial growth factor, original magnification ×20 [inset in bottom right corner]). |

|

| Figure 6. A radiograph of the left hand revealed small sporadic areas of sclerosis in the substantia spongiosa on the heads of some phalanges (white arrows). |

Radiographic imaging of the hands and feet revealed numerous small, ovoid or round foci of sclerosis that were a few millimeters in diameter and were occasionally confluent. This finding was prevalent on the carpal and tarsal bones but less evident on the phalanges and the epiphysis of the metatarsal and metacarpal bones. Full radiographic imaging of both arms and legs subsequently was obtained and showed similar lesions predominantly in the substantia spongiosa of the metaphyses and the epiphyses of the humerus, femur, tibia, and fibula bilaterally (Figure 3). Evaluation of the patient’s parents revealed that her mother had sporadic lenticular areas of increased bone density seen on radiography of the carpal and tarsal bones, particularly at the level of calcaneus, and the proximal and distal humeral epiphyses.

These lesions in our patient were consistent with an incomplete form of osteopoikilosis, which reflects the known variable expression of BOS. The radiologic findings in addition to the cutaneous lesions and the positive family history supported a diagnosis of BOS.

Patient 2

A 5-year-old boy presented with multiple congenital, asymptomatic, flesh-colored papules with elastic consistency on the left thigh, back, and pubic area that were characteristic of dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata (Figure 4). The patient’s 7-year-old sister had similar cutaneous lesions. The patient underwent a skin biopsy from the back that revealed thickening of collagen bundles in the dermis with an increase in elastic fibers (Figure 5). On radiographic imaging, small sporadic areas of sclerosis were noted in the substantia spongiosa of the lateral aspect of the humeral capitulum, the radial neck, the capitate, the head of the proximal phalanx of the fourth finger on the left hand, and the heads of the third and fifth middle phalanges on the left hand (Figure 6). Radiography revealed osteopoikilosis on both humeral heads in the patient’s mother. These findings in addition to the dermatologic and histopathologic features suggested a diagnosis of BOS.

Comment

In 1928, Buschke and Ollendorff1 first reported the association between osteopoikilosis and dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata, which showed autosomal-dominant inheritance. Skin and bone lesions can occur independently in different family members. Two different clinical cutaneous patterns are described in BOS.2-4 The first and most frequent form is characterized by yellowish nodules often grouped in plaques that are asymmetrically distributed, such as those seen in patient 1. The second form is known as dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata, which was seen in patient 2. Histologically, most lesions show normal collagen fibrils and an increased number of elastic fibers.

Osteopoikilosis, also known as spotted bone disease or osteopathia condensans, is a rare asymptomatic bone dysplasia of unknown etiology. It is characterized by an abnormality in the bone maturation process and often is found incidentally on radiologic examination, as seen in patient 1. Radiologic signs of osteopoikilosis consist of small, disseminated, well-circumscribed areas of increased radiodensity located in the epiphyses and metaphyses of long bones, as well as the pelvis, hands, and feet. These lesions, which typically are asymptomatic, could sometimes be associated with bone and/or joint pain but do not cause a predisposition to fractures. Documentation of these bone lesions by early adult life is important to avoid confusion with osteoblastic metastases on the skeleton.6

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome is characterized by a variable expression. Loss-of-function mutations of the LEMD3 gene have been described in association with this disorder.7 This gene encodes an inner nuclear protein membrane with a C-terminal domain that binds SMAD2 and SMAD3 and antagonizes the bone morphogenetic proteins and transforming growth factor b. These proteins are involved in connective tissue morphogenesis, inducing elastin production from fibroblasts.7 Seven novel loss-of-function mutations of LEMD3 have been identified.8 The segmental manifestation of BOS could be a consequence of the mosaicism resulting from a somatic mutation.9,10 A case describing the absence of LEMD3 mutation in an affected family suggested the genetic heterogeneity of BOS.11

Conclusion

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome is a benign condition with no repercussions on the patient’s health or quality of life. It does not require any specific treatment because the lesions generally remain asymptomatic and do not generate any substantial cosmetic burden. Mutation analysis was not performed in our patients because BOS has a good prognosis and the parents refused further investigation in both patients; therefore, a correct diagnosis was essential in our cases to rule out malignant bone disease in patient 1 whose osteopoikilosis prompted the workup and other disorders (eg, tuberous sclerosis, pseudoxanthoma elasticum) in patient 2 whose cutaneous lesions were the primary cause for presentation. A correct diagnosis of BOS is necessary to spare patients from expensive investigations and to provide reassurance about the benign nature of the disease.

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome (BOS) is a rare disease that is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with high penetrance. It is characterized by osteopoikilosis associated with skin manifestations. The approximate incidence of the disease is 1:20,000, with few cases reported in the literature since 1928.1 Skeletal lesions known as osteopoikilosis are areas of increased bone density that can be seen on radiographic imaging and typically are located in the substantia spongiosa of the epiphyses and metaphyses of long bones and the pelvis. In BOS, cutaneous lesions consist of elastic or collagen nevi. Phenotypic expression of the disease is variable, and skeletal and cutaneous lesions may occur separately. Gene mutations of proteins involved in bone and connective tissue morphogenesis have been described in patients with BOS.2-5

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 17-year-old adolescent girl was referred to our hospital for evaluation of an incidental finding of osteopoikilosis that had been noted in the setting of a traumatic event. Clinical examination revealed cutaneous lesions characterized by asymptomatic, linear, stringlike and atrophic fibrotic plaques localized symmetrically on the trunk, right buttock, and right thigh (Figure 1). The lesions on the thigh were present at birth and had spread progressively to the other areas. There was no known history of inflammatory skin disease to explain the presence of the lesions, and no family history of similar signs or symptoms was reported. Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy of a plaque from the trunk revealed increased collagen bundles associated with thick interlacing elastic fibers. The epidermis did not show any specific histologic alterations. These histopathologic features were diagnostic of a connective tissue nevus (Figure 2).

|

Figure 1. An asymptomatic atrophic fibrotic plaque localized on the right thigh. |

|

Figure 2. Low-power view of a punch biopsy showing a normal epidermis. Collagen bundles of the dermis were thickened and somewhat homogenized, as highlighted by the Masson stain (original magnification ×2.5). |

|

Figure 3. Radiograph of the legs revealed numerous small, ovoid or round foci of sclerosis on the substantia spongiosa of the metaphyses and the epiphyses of the femur, tibia, and fibula on both sides of the body. |

|

Figure 4. Multiple asymptomatic flesh-colored papules with elastic consistency on the back that were characteristic of dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata. |

|

Figure 5. The epidermis and dermis appeared normal on histopathology; however, the elastic fibers were markedly increased in both size and number up to the deep dermis in the absence of degenerating changes (H&E, original magnification ×2.5; vascular endothelial growth factor, original magnification ×20 [inset in bottom right corner]). |

|

| Figure 6. A radiograph of the left hand revealed small sporadic areas of sclerosis in the substantia spongiosa on the heads of some phalanges (white arrows). |

Radiographic imaging of the hands and feet revealed numerous small, ovoid or round foci of sclerosis that were a few millimeters in diameter and were occasionally confluent. This finding was prevalent on the carpal and tarsal bones but less evident on the phalanges and the epiphysis of the metatarsal and metacarpal bones. Full radiographic imaging of both arms and legs subsequently was obtained and showed similar lesions predominantly in the substantia spongiosa of the metaphyses and the epiphyses of the humerus, femur, tibia, and fibula bilaterally (Figure 3). Evaluation of the patient’s parents revealed that her mother had sporadic lenticular areas of increased bone density seen on radiography of the carpal and tarsal bones, particularly at the level of calcaneus, and the proximal and distal humeral epiphyses.

These lesions in our patient were consistent with an incomplete form of osteopoikilosis, which reflects the known variable expression of BOS. The radiologic findings in addition to the cutaneous lesions and the positive family history supported a diagnosis of BOS.

Patient 2

A 5-year-old boy presented with multiple congenital, asymptomatic, flesh-colored papules with elastic consistency on the left thigh, back, and pubic area that were characteristic of dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata (Figure 4). The patient’s 7-year-old sister had similar cutaneous lesions. The patient underwent a skin biopsy from the back that revealed thickening of collagen bundles in the dermis with an increase in elastic fibers (Figure 5). On radiographic imaging, small sporadic areas of sclerosis were noted in the substantia spongiosa of the lateral aspect of the humeral capitulum, the radial neck, the capitate, the head of the proximal phalanx of the fourth finger on the left hand, and the heads of the third and fifth middle phalanges on the left hand (Figure 6). Radiography revealed osteopoikilosis on both humeral heads in the patient’s mother. These findings in addition to the dermatologic and histopathologic features suggested a diagnosis of BOS.

Comment

In 1928, Buschke and Ollendorff1 first reported the association between osteopoikilosis and dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata, which showed autosomal-dominant inheritance. Skin and bone lesions can occur independently in different family members. Two different clinical cutaneous patterns are described in BOS.2-4 The first and most frequent form is characterized by yellowish nodules often grouped in plaques that are asymmetrically distributed, such as those seen in patient 1. The second form is known as dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata, which was seen in patient 2. Histologically, most lesions show normal collagen fibrils and an increased number of elastic fibers.

Osteopoikilosis, also known as spotted bone disease or osteopathia condensans, is a rare asymptomatic bone dysplasia of unknown etiology. It is characterized by an abnormality in the bone maturation process and often is found incidentally on radiologic examination, as seen in patient 1. Radiologic signs of osteopoikilosis consist of small, disseminated, well-circumscribed areas of increased radiodensity located in the epiphyses and metaphyses of long bones, as well as the pelvis, hands, and feet. These lesions, which typically are asymptomatic, could sometimes be associated with bone and/or joint pain but do not cause a predisposition to fractures. Documentation of these bone lesions by early adult life is important to avoid confusion with osteoblastic metastases on the skeleton.6

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome is characterized by a variable expression. Loss-of-function mutations of the LEMD3 gene have been described in association with this disorder.7 This gene encodes an inner nuclear protein membrane with a C-terminal domain that binds SMAD2 and SMAD3 and antagonizes the bone morphogenetic proteins and transforming growth factor b. These proteins are involved in connective tissue morphogenesis, inducing elastin production from fibroblasts.7 Seven novel loss-of-function mutations of LEMD3 have been identified.8 The segmental manifestation of BOS could be a consequence of the mosaicism resulting from a somatic mutation.9,10 A case describing the absence of LEMD3 mutation in an affected family suggested the genetic heterogeneity of BOS.11

Conclusion

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome is a benign condition with no repercussions on the patient’s health or quality of life. It does not require any specific treatment because the lesions generally remain asymptomatic and do not generate any substantial cosmetic burden. Mutation analysis was not performed in our patients because BOS has a good prognosis and the parents refused further investigation in both patients; therefore, a correct diagnosis was essential in our cases to rule out malignant bone disease in patient 1 whose osteopoikilosis prompted the workup and other disorders (eg, tuberous sclerosis, pseudoxanthoma elasticum) in patient 2 whose cutaneous lesions were the primary cause for presentation. A correct diagnosis of BOS is necessary to spare patients from expensive investigations and to provide reassurance about the benign nature of the disease.

1. Buschke A, Ollendorff H. Ein fall von dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata und osteopathia condensas disseminata. Derm Worchenschr. 1928;86:257-262.

2. Ramme K, Kolde G, Stadler R. Dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata with osteopoikilosis. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome [in German]. Hautarzt. 1993;44:312-314.

3. Schena D, Germi L, Zamperetti MR, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1159-1161.

4. Kawamura A, Ochiai T, Tan-Kinoshita M, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome: three generations in a Japanese family. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:133-137.

5. Woodrow SL, Pope FM, Handfield-Jones SE. The Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome presenting as familial elastic tissue naevi. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:890-893.

6. Whyte MP, Murphy WA, Siegel BA. 99mTc-pyrophosphate bone imaging in osteopoikilosis, osteopathia striata, and melorheostosis. Radiology. 1978;127:439-443.

7. Giro MG, Duvic M, Smith LT, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome associated with elevated elastin production by affected skin fibroblasts in culture. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:129-137.

8. Hellemans J, Preobrazhenska O, Willaert A, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in LEMD3 result in osteopoikilosis, Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome and melorheostosis [published online ahead of print October 17, 2004]. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1213-1218.

9. Ehrig T, Cockerell CJ. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome: report of a case and interpretation of the clinical phenotype as a type 2 segmental manifestation of an autosomal dominant skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1163-1166.

10. Hellemans J, Debeer P, Wright M, et al. Germline LEMD3 mutations are rare in sporadic patients with isolated melorheostosis. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:290.

11. Yadegari M, Whyte MP, Mumm S, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome: absence of LEMD3 mutation in an affected family. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:63-68.

1. Buschke A, Ollendorff H. Ein fall von dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata und osteopathia condensas disseminata. Derm Worchenschr. 1928;86:257-262.

2. Ramme K, Kolde G, Stadler R. Dermatofibrosis lenticularis disseminata with osteopoikilosis. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome [in German]. Hautarzt. 1993;44:312-314.

3. Schena D, Germi L, Zamperetti MR, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1159-1161.

4. Kawamura A, Ochiai T, Tan-Kinoshita M, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome: three generations in a Japanese family. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:133-137.

5. Woodrow SL, Pope FM, Handfield-Jones SE. The Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome presenting as familial elastic tissue naevi. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:890-893.

6. Whyte MP, Murphy WA, Siegel BA. 99mTc-pyrophosphate bone imaging in osteopoikilosis, osteopathia striata, and melorheostosis. Radiology. 1978;127:439-443.

7. Giro MG, Duvic M, Smith LT, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome associated with elevated elastin production by affected skin fibroblasts in culture. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:129-137.

8. Hellemans J, Preobrazhenska O, Willaert A, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in LEMD3 result in osteopoikilosis, Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome and melorheostosis [published online ahead of print October 17, 2004]. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1213-1218.

9. Ehrig T, Cockerell CJ. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome: report of a case and interpretation of the clinical phenotype as a type 2 segmental manifestation of an autosomal dominant skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1163-1166.

10. Hellemans J, Debeer P, Wright M, et al. Germline LEMD3 mutations are rare in sporadic patients with isolated melorheostosis. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:290.

11. Yadegari M, Whyte MP, Mumm S, et al. Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome: absence of LEMD3 mutation in an affected family. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:63-68.

Practice Points

- Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome (BOS) is an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by the rare association of skin lesions consisting of collagen or elastic nevi and bone lesions known as osteopoikilosis that are reported radiologically.

- Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome is characterized by elevated genetic heterogeneity and is transmitted with a variable expression.

- Although BOS is a benign condition and does not require any treatment, a correct diagnosis is important to spare patients from unnecessary investigations.