User login

Granuloma Annulare Presenting as Firm Nodules on the Forehead and Scalp in a Child

To the Editor:

A 3.5-year-old boy presented with asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules on the left side of the forehead and frontal scalp of approximately 6 months’ duration. There was no history of trauma or preceding rash. His medical history was remarkable only for allergic rhinitis. A review of systems was otherwise negative. Computed tomography ordered by the patient’s pediatrician prior to referral to dermatology showed soft tissue masses on the forehead and frontal scalp with no associated bone or brain parenchymal signal abnormalities.

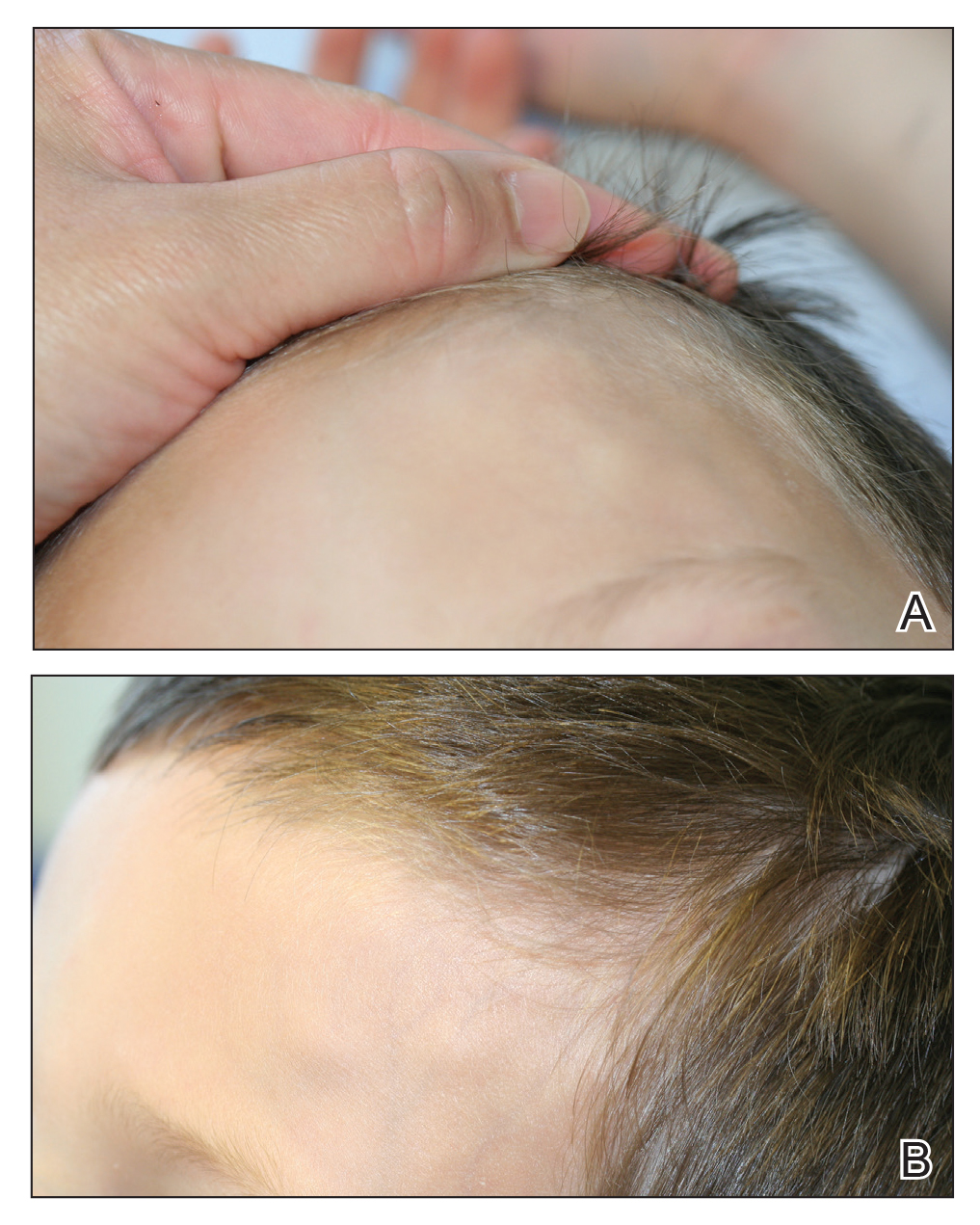

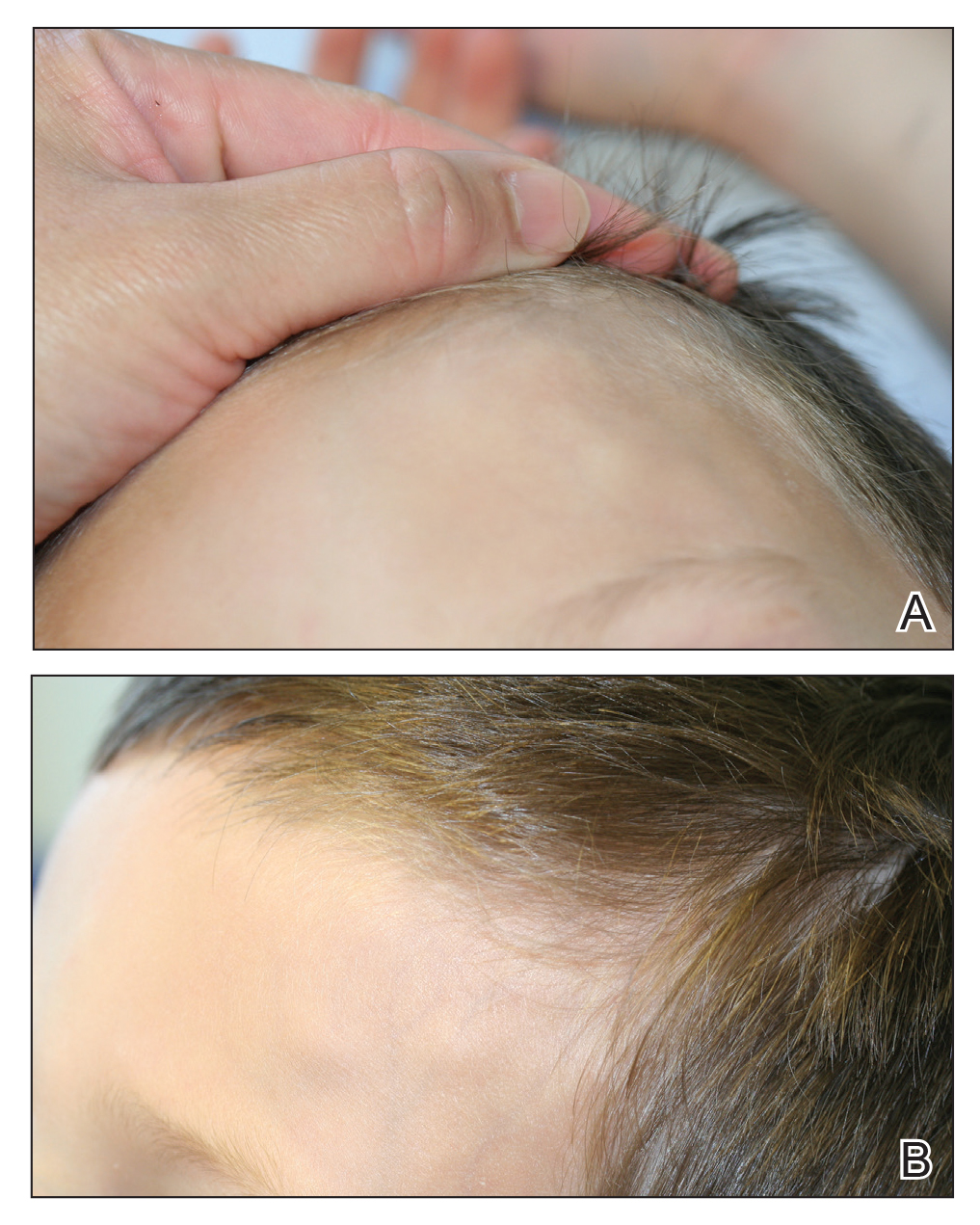

At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed a 6×7-cm, flesh-colored cluster of firm, nontender, fixed, subcutaneous nodules on the left superior forehead and anterior part of the left frontal scalp (Figure 1A), as well as 2×1.5-cm, firm, fixed, flesh-colored nodule inferior to the larger cluster of lesions (Figure 1B). The remainder of the skin examination was unremarkable.

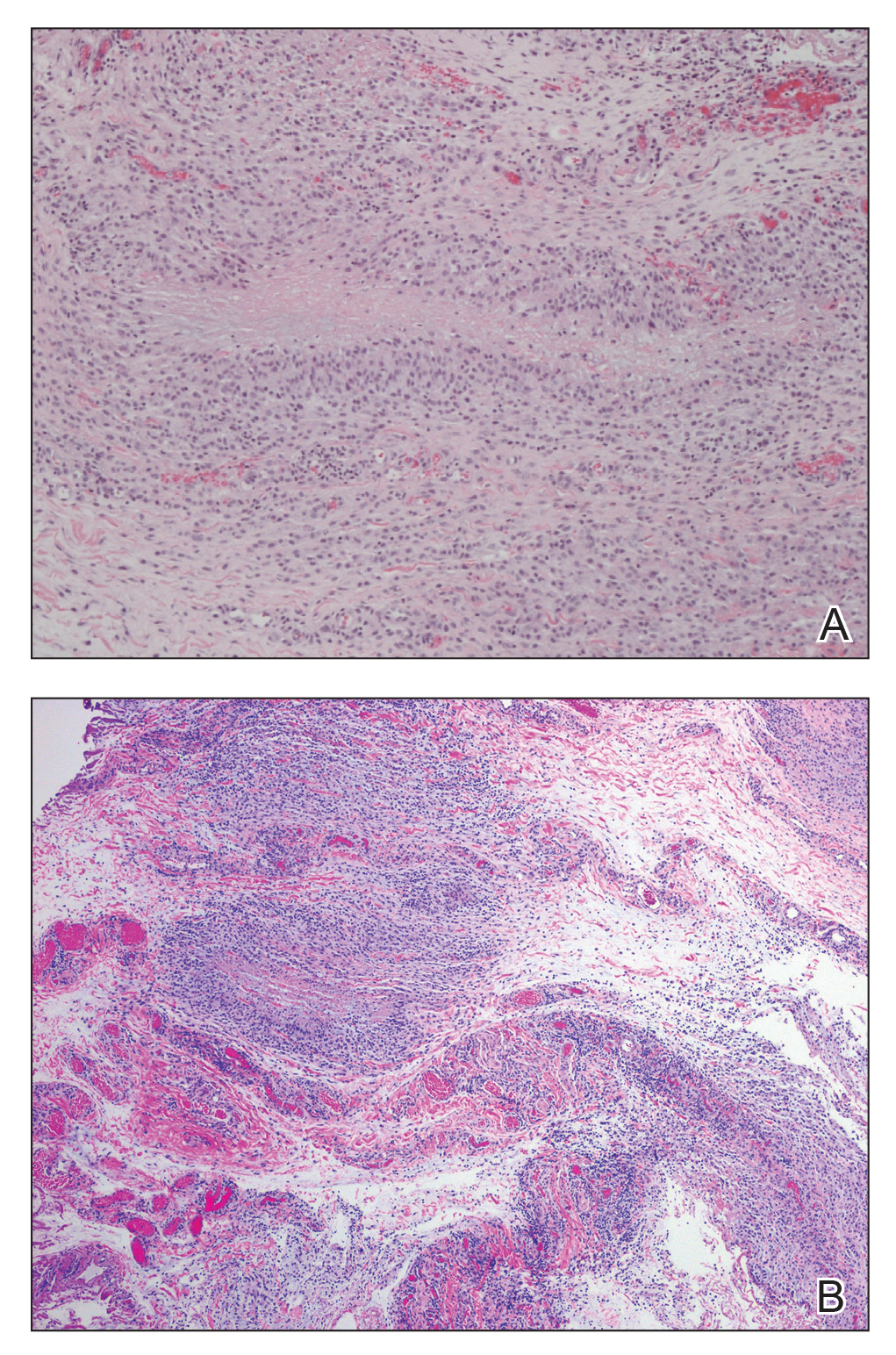

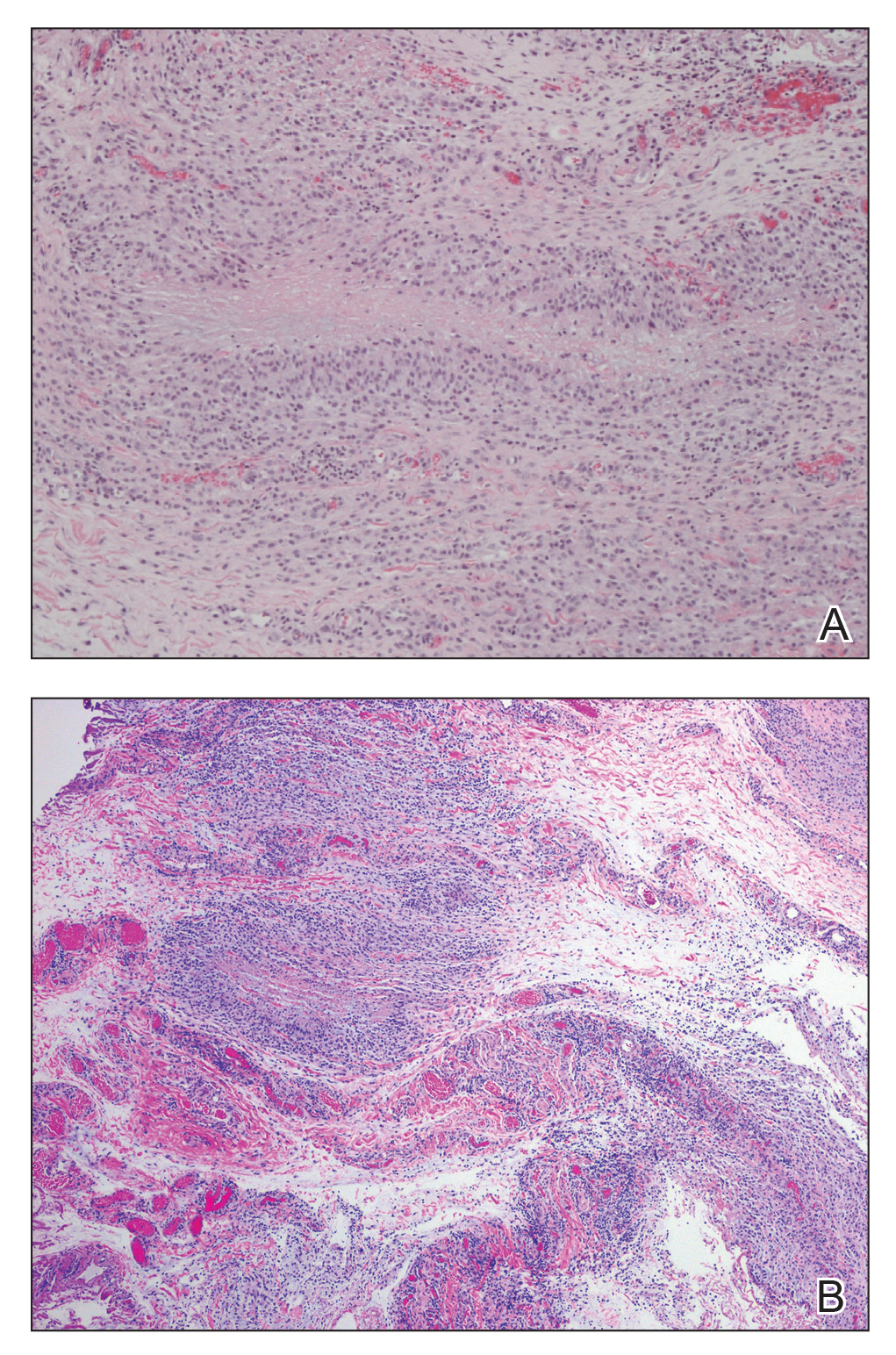

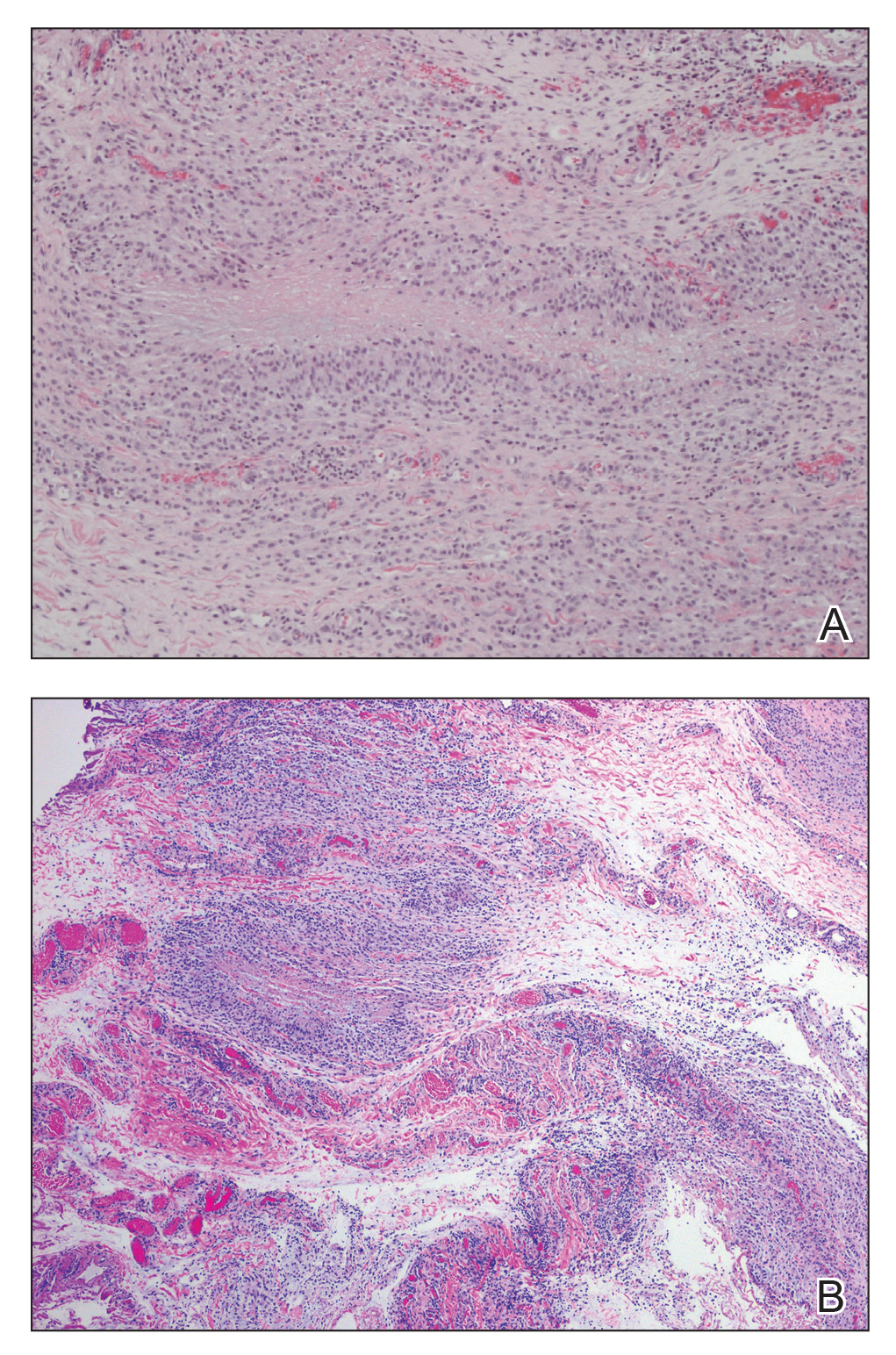

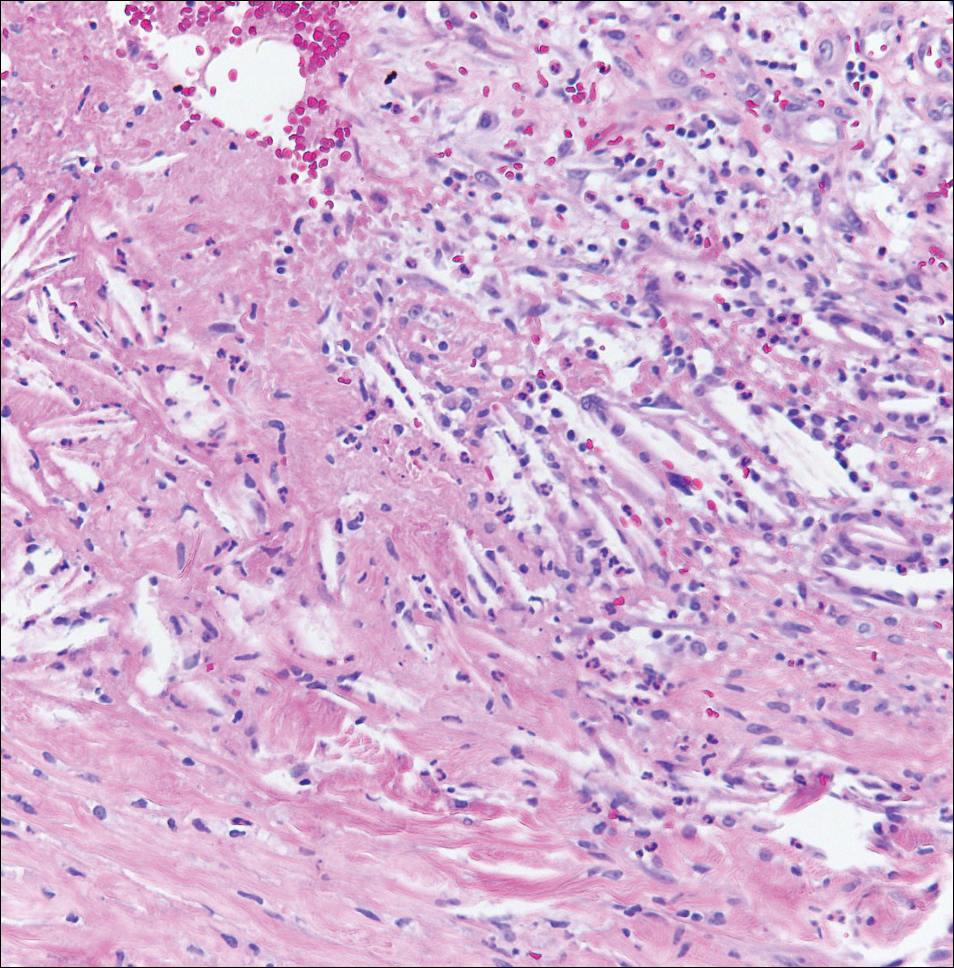

The patient was referred to plastic surgery for an incisional biopsy. The histopathologic findings demonstrated a marked mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes with rare eosinophils and neutrophils in the subcutaneous tissue. The histiocytes were arranged in a palisading pattern surrounding central areas of necrosis (Figure 2). These features were consistent with a diagnosis of subcutaneous granuloma annulare (GA).

After the histologic diagnosis was elucidated, the patient’s family was provided reassurance regarding the benign nature and self-resolving course of GA in most children. No treatment was initiated, and no further laboratory studies or imaging were performed. At 9-month follow-up, the nodules were considerably smaller, and the patient remained asymptomatic.

Granuloma annulare is a benign dermatosis that presents in various forms, including localized, generalized, perforating, and subcutaneous subtypes. Subcutaneous GA (SGA) occurs most commonly in young children. The typical presentation of SGA is single or multiple flesh-colored to pink subcutaneous nodules on the arms, legs, or scalp.1 On the scalp, SGA has a predilection for the parietal and occipital regions. In some cases, there may be a history of preceding trauma to the area. Typically, lesions on the arms and legs are mobile whereas lesions on the scalp may be fixed due to their close proximity to the periosteum. Patients often are asymptomatic, and in the majority of cases, lesions resolve spontaneously over several months to years. Approximately 50% of cases resolve within 2 years of onset.2

Histologically, SGA appears as a nodule of fibrinoid or necrotic degeneration surrounded by palisaded histiocytes and lymphocytes in the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare is an accurate term for our case due to the subcutaneous location of the granulomatous change; however, some practitioners may prefer to use the term deep GA when the histologic findings are in the deep dermis vs the subcutis. Often, prominent deposition of mucin may be found. Histologically, SGA can closely resemble a rheumatoid nodule or necrobiosis lipoidica.1

Subcutaneous GA presenting on the scalp and forehead, such as in our case, can present a diagnostic challenge due to the extensive differential diagnoses that must be considered, including trauma, infection, bone or skin disease, and inflammatory or autoimmune disease.2,3 Additionally, the firm fixed characteristics of some lesions may raise additional concerns for possible malignant diagnoses such as epithelial sarcoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis, as highlighted by Agrawal et al.4 For these reasons, imaging and biopsy often are necessary for histologic diagnosis.

There is no consensus on the etiology of SGA, and no specific disease associations have been proven. Some case reports and case series have proposed a link between SGA and type 1 diabetes mellitus.1,4 In one retrospective case series, Grogg and Nascimento1 found that 2 of 34 (5.9%) pediatric patients with SGA had known or subsequently diagnosed diabetes mellitus; however, a definitive association between the 2 entities has not been elucidated. Underlying type 1 diabetes mellitus should be considered in patients with isolated SGA, but laboratory screening for diabetes is not necessary in patients with a negative review of systems.

Treatment of SGA typically is not required, as it is a self-limited condition. Often, once a histologic diagnosis is established, no further evaluation or treatment is warranted. Multiple treatment modalities have been reported, including intralesional and topical corticosteroids, laser therapy, cryotherapy, and systemic agents such as isotretinoin or corticosteroids; however, no treatment has been shown to be consistently efficacious.5 Excision of the lesions may be performed, but the risk for recurrence often precludes it as a viable option. In some case series, there have been recurrence rates as high as 40% to 75% in the months to years following surgical excision/biopsy.1,6

Patients presenting with presumed SGA should undergo a thorough history, review of systems, and full-body skin examination. In some cases, imaging and biopsy may be necessary to make a definitive diagnosis and exclude a more serious condition.

- Grogg KL, Nascimento AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare in childhood: clinicopathologic features in 34 cases. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E42.

- Sabuncuoglu H, Oge K, Soylemezoglu F, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare of the scalp in childhood: a case report and review of the literature. Turk Neurosurg. 2007;17:19-22.

- Whelan JP, Zembowicz A. A 22-month-old boy with the rapid growth of subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2697-2704.

- Agrawal AK, Kammen BF, Guo H, et al. An unusual presentation of subcutaneous granuloma annulare in association with juvenile-onset diabetes: case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:202-205.

- Cronquist SD, Stashower ME, Benson PM. Deep dermal granuloma annulare presenting as an eyelid tumor in a child, with review of pediatric eyelid lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:377-380.

- Jankowski PP, Krishna PH, Rutledge JC, et al. Surgical management and outcome of scalp subcutaneous granuloma annulare in children: case report. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:E1002, discussion E1002.

To the Editor:

A 3.5-year-old boy presented with asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules on the left side of the forehead and frontal scalp of approximately 6 months’ duration. There was no history of trauma or preceding rash. His medical history was remarkable only for allergic rhinitis. A review of systems was otherwise negative. Computed tomography ordered by the patient’s pediatrician prior to referral to dermatology showed soft tissue masses on the forehead and frontal scalp with no associated bone or brain parenchymal signal abnormalities.

At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed a 6×7-cm, flesh-colored cluster of firm, nontender, fixed, subcutaneous nodules on the left superior forehead and anterior part of the left frontal scalp (Figure 1A), as well as 2×1.5-cm, firm, fixed, flesh-colored nodule inferior to the larger cluster of lesions (Figure 1B). The remainder of the skin examination was unremarkable.

The patient was referred to plastic surgery for an incisional biopsy. The histopathologic findings demonstrated a marked mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes with rare eosinophils and neutrophils in the subcutaneous tissue. The histiocytes were arranged in a palisading pattern surrounding central areas of necrosis (Figure 2). These features were consistent with a diagnosis of subcutaneous granuloma annulare (GA).

After the histologic diagnosis was elucidated, the patient’s family was provided reassurance regarding the benign nature and self-resolving course of GA in most children. No treatment was initiated, and no further laboratory studies or imaging were performed. At 9-month follow-up, the nodules were considerably smaller, and the patient remained asymptomatic.

Granuloma annulare is a benign dermatosis that presents in various forms, including localized, generalized, perforating, and subcutaneous subtypes. Subcutaneous GA (SGA) occurs most commonly in young children. The typical presentation of SGA is single or multiple flesh-colored to pink subcutaneous nodules on the arms, legs, or scalp.1 On the scalp, SGA has a predilection for the parietal and occipital regions. In some cases, there may be a history of preceding trauma to the area. Typically, lesions on the arms and legs are mobile whereas lesions on the scalp may be fixed due to their close proximity to the periosteum. Patients often are asymptomatic, and in the majority of cases, lesions resolve spontaneously over several months to years. Approximately 50% of cases resolve within 2 years of onset.2

Histologically, SGA appears as a nodule of fibrinoid or necrotic degeneration surrounded by palisaded histiocytes and lymphocytes in the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare is an accurate term for our case due to the subcutaneous location of the granulomatous change; however, some practitioners may prefer to use the term deep GA when the histologic findings are in the deep dermis vs the subcutis. Often, prominent deposition of mucin may be found. Histologically, SGA can closely resemble a rheumatoid nodule or necrobiosis lipoidica.1

Subcutaneous GA presenting on the scalp and forehead, such as in our case, can present a diagnostic challenge due to the extensive differential diagnoses that must be considered, including trauma, infection, bone or skin disease, and inflammatory or autoimmune disease.2,3 Additionally, the firm fixed characteristics of some lesions may raise additional concerns for possible malignant diagnoses such as epithelial sarcoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis, as highlighted by Agrawal et al.4 For these reasons, imaging and biopsy often are necessary for histologic diagnosis.

There is no consensus on the etiology of SGA, and no specific disease associations have been proven. Some case reports and case series have proposed a link between SGA and type 1 diabetes mellitus.1,4 In one retrospective case series, Grogg and Nascimento1 found that 2 of 34 (5.9%) pediatric patients with SGA had known or subsequently diagnosed diabetes mellitus; however, a definitive association between the 2 entities has not been elucidated. Underlying type 1 diabetes mellitus should be considered in patients with isolated SGA, but laboratory screening for diabetes is not necessary in patients with a negative review of systems.

Treatment of SGA typically is not required, as it is a self-limited condition. Often, once a histologic diagnosis is established, no further evaluation or treatment is warranted. Multiple treatment modalities have been reported, including intralesional and topical corticosteroids, laser therapy, cryotherapy, and systemic agents such as isotretinoin or corticosteroids; however, no treatment has been shown to be consistently efficacious.5 Excision of the lesions may be performed, but the risk for recurrence often precludes it as a viable option. In some case series, there have been recurrence rates as high as 40% to 75% in the months to years following surgical excision/biopsy.1,6

Patients presenting with presumed SGA should undergo a thorough history, review of systems, and full-body skin examination. In some cases, imaging and biopsy may be necessary to make a definitive diagnosis and exclude a more serious condition.

To the Editor:

A 3.5-year-old boy presented with asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules on the left side of the forehead and frontal scalp of approximately 6 months’ duration. There was no history of trauma or preceding rash. His medical history was remarkable only for allergic rhinitis. A review of systems was otherwise negative. Computed tomography ordered by the patient’s pediatrician prior to referral to dermatology showed soft tissue masses on the forehead and frontal scalp with no associated bone or brain parenchymal signal abnormalities.

At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed a 6×7-cm, flesh-colored cluster of firm, nontender, fixed, subcutaneous nodules on the left superior forehead and anterior part of the left frontal scalp (Figure 1A), as well as 2×1.5-cm, firm, fixed, flesh-colored nodule inferior to the larger cluster of lesions (Figure 1B). The remainder of the skin examination was unremarkable.

The patient was referred to plastic surgery for an incisional biopsy. The histopathologic findings demonstrated a marked mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes with rare eosinophils and neutrophils in the subcutaneous tissue. The histiocytes were arranged in a palisading pattern surrounding central areas of necrosis (Figure 2). These features were consistent with a diagnosis of subcutaneous granuloma annulare (GA).

After the histologic diagnosis was elucidated, the patient’s family was provided reassurance regarding the benign nature and self-resolving course of GA in most children. No treatment was initiated, and no further laboratory studies or imaging were performed. At 9-month follow-up, the nodules were considerably smaller, and the patient remained asymptomatic.

Granuloma annulare is a benign dermatosis that presents in various forms, including localized, generalized, perforating, and subcutaneous subtypes. Subcutaneous GA (SGA) occurs most commonly in young children. The typical presentation of SGA is single or multiple flesh-colored to pink subcutaneous nodules on the arms, legs, or scalp.1 On the scalp, SGA has a predilection for the parietal and occipital regions. In some cases, there may be a history of preceding trauma to the area. Typically, lesions on the arms and legs are mobile whereas lesions on the scalp may be fixed due to their close proximity to the periosteum. Patients often are asymptomatic, and in the majority of cases, lesions resolve spontaneously over several months to years. Approximately 50% of cases resolve within 2 years of onset.2

Histologically, SGA appears as a nodule of fibrinoid or necrotic degeneration surrounded by palisaded histiocytes and lymphocytes in the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare is an accurate term for our case due to the subcutaneous location of the granulomatous change; however, some practitioners may prefer to use the term deep GA when the histologic findings are in the deep dermis vs the subcutis. Often, prominent deposition of mucin may be found. Histologically, SGA can closely resemble a rheumatoid nodule or necrobiosis lipoidica.1

Subcutaneous GA presenting on the scalp and forehead, such as in our case, can present a diagnostic challenge due to the extensive differential diagnoses that must be considered, including trauma, infection, bone or skin disease, and inflammatory or autoimmune disease.2,3 Additionally, the firm fixed characteristics of some lesions may raise additional concerns for possible malignant diagnoses such as epithelial sarcoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis, as highlighted by Agrawal et al.4 For these reasons, imaging and biopsy often are necessary for histologic diagnosis.

There is no consensus on the etiology of SGA, and no specific disease associations have been proven. Some case reports and case series have proposed a link between SGA and type 1 diabetes mellitus.1,4 In one retrospective case series, Grogg and Nascimento1 found that 2 of 34 (5.9%) pediatric patients with SGA had known or subsequently diagnosed diabetes mellitus; however, a definitive association between the 2 entities has not been elucidated. Underlying type 1 diabetes mellitus should be considered in patients with isolated SGA, but laboratory screening for diabetes is not necessary in patients with a negative review of systems.

Treatment of SGA typically is not required, as it is a self-limited condition. Often, once a histologic diagnosis is established, no further evaluation or treatment is warranted. Multiple treatment modalities have been reported, including intralesional and topical corticosteroids, laser therapy, cryotherapy, and systemic agents such as isotretinoin or corticosteroids; however, no treatment has been shown to be consistently efficacious.5 Excision of the lesions may be performed, but the risk for recurrence often precludes it as a viable option. In some case series, there have been recurrence rates as high as 40% to 75% in the months to years following surgical excision/biopsy.1,6

Patients presenting with presumed SGA should undergo a thorough history, review of systems, and full-body skin examination. In some cases, imaging and biopsy may be necessary to make a definitive diagnosis and exclude a more serious condition.

- Grogg KL, Nascimento AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare in childhood: clinicopathologic features in 34 cases. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E42.

- Sabuncuoglu H, Oge K, Soylemezoglu F, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare of the scalp in childhood: a case report and review of the literature. Turk Neurosurg. 2007;17:19-22.

- Whelan JP, Zembowicz A. A 22-month-old boy with the rapid growth of subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2697-2704.

- Agrawal AK, Kammen BF, Guo H, et al. An unusual presentation of subcutaneous granuloma annulare in association with juvenile-onset diabetes: case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:202-205.

- Cronquist SD, Stashower ME, Benson PM. Deep dermal granuloma annulare presenting as an eyelid tumor in a child, with review of pediatric eyelid lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:377-380.

- Jankowski PP, Krishna PH, Rutledge JC, et al. Surgical management and outcome of scalp subcutaneous granuloma annulare in children: case report. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:E1002, discussion E1002.

- Grogg KL, Nascimento AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare in childhood: clinicopathologic features in 34 cases. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E42.

- Sabuncuoglu H, Oge K, Soylemezoglu F, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare of the scalp in childhood: a case report and review of the literature. Turk Neurosurg. 2007;17:19-22.

- Whelan JP, Zembowicz A. A 22-month-old boy with the rapid growth of subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2697-2704.

- Agrawal AK, Kammen BF, Guo H, et al. An unusual presentation of subcutaneous granuloma annulare in association with juvenile-onset diabetes: case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:202-205.

- Cronquist SD, Stashower ME, Benson PM. Deep dermal granuloma annulare presenting as an eyelid tumor in a child, with review of pediatric eyelid lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:377-380.

- Jankowski PP, Krishna PH, Rutledge JC, et al. Surgical management and outcome of scalp subcutaneous granuloma annulare in children: case report. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:E1002, discussion E1002.

Practice Points

- Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (GA) is an important diagnosis to consider in the differential of subcutaneous nodules in children.

- The subcutaneous variant of GA can present without any typical GA lesions.

- Subcutaneous GA typically has a self-resolving course in most children.

Irregular Yellow-Brown Plaques on the Trunk and Thighs

The Diagnosis: Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

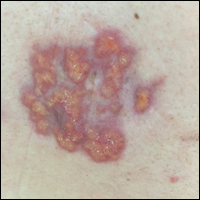

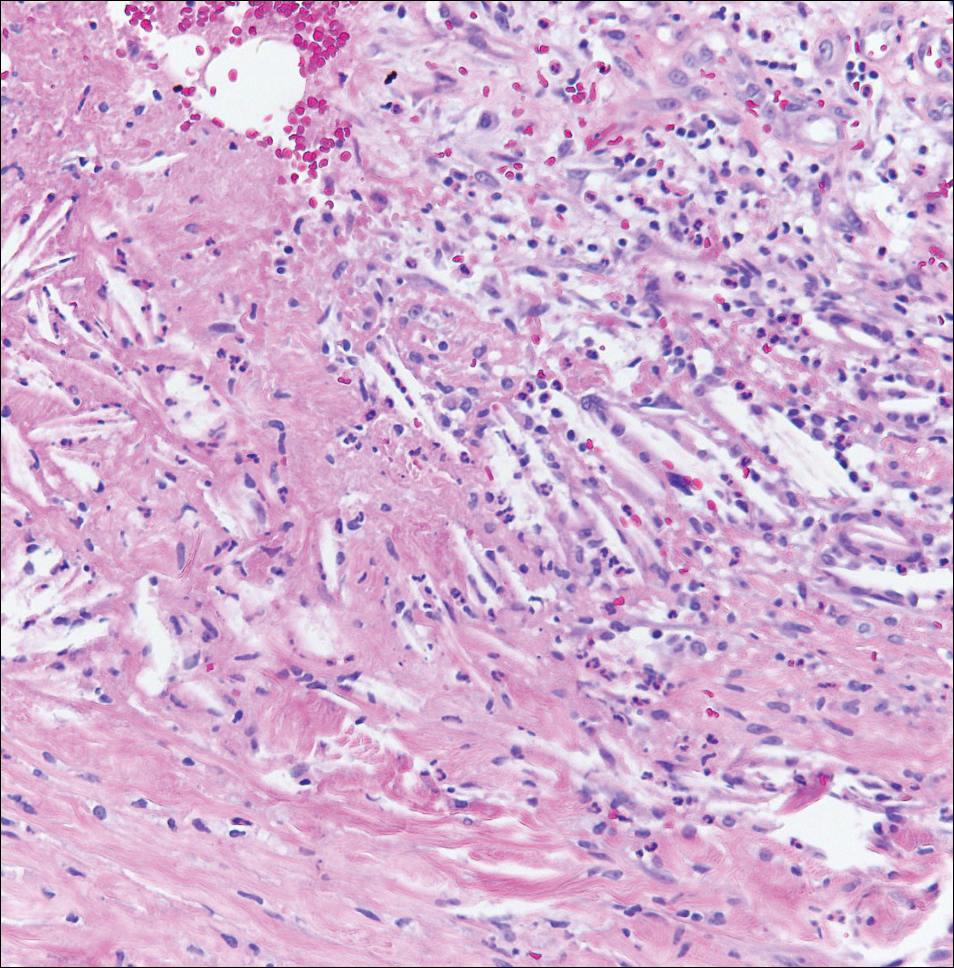

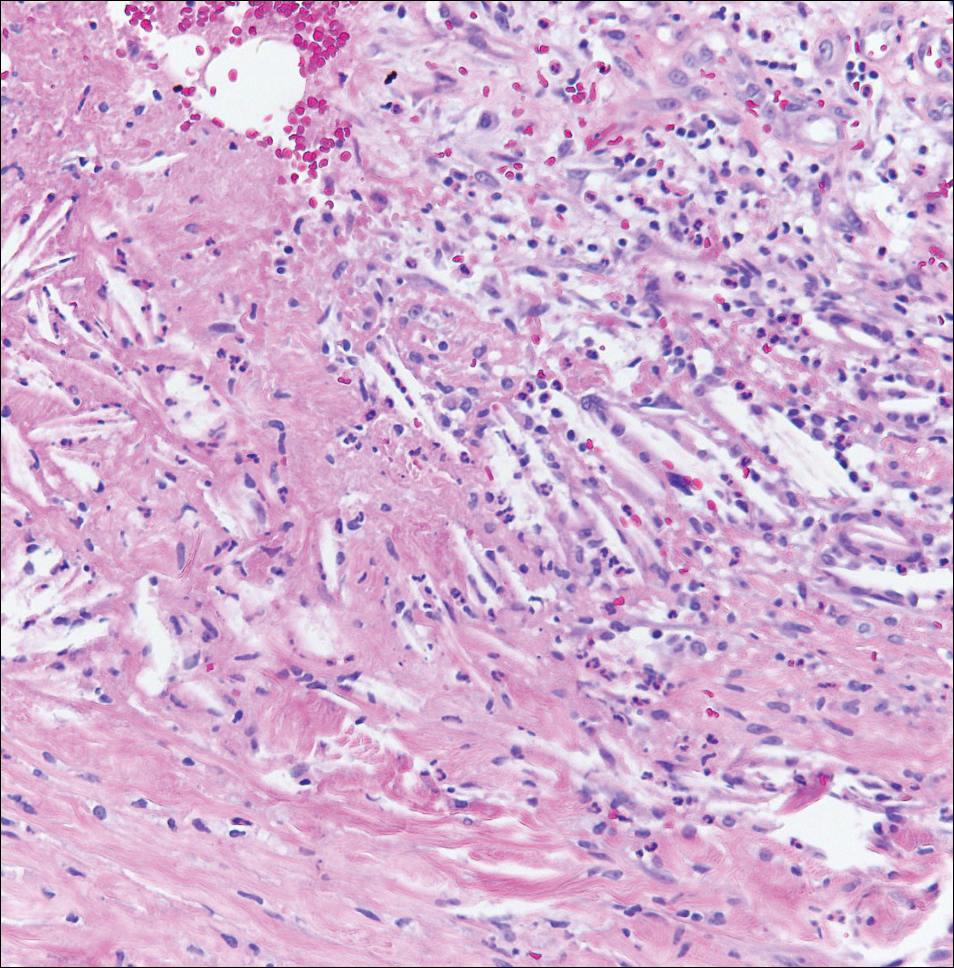

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed for routine stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, xanthoma disseminatum, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure). There were surrounding areas of degenerated collagen containing numerous cholesterol clefts. After clinical pathologic correlation, a diagnosis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) was elucidated.

The patient was referred to general surgery for elective excision of 1 or more of the lesions. Excision of an abdominal lesion was performed without complication. After several months, a new lesion reformed within the excisional scar that also was consistent with NXG. At further dermatologic visits, a trial of intralesional corticosteroids was attempted to the largest lesions with modest improvement. In addition, follow-up with hematology and oncology was recommended for routine surveillance of the known blood dyscrasia.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a multisystem non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disease. Clinically, NXG is characterized by infiltrative plaques and ulcerative nodules. Lesions may appear red, brown, or yellow with associated atrophy and telangiectasia.1 Koch et al2 described a predilection for granuloma formation within preexisting scars. Periorbital location is the most common cutaneous site of involvement of NXG, seen in 80% of cases, but the trunk and extremities also may be involved.1,3 Approximately half of those with periocular involvement experience ocular symptoms including prop- tosis, blepharoptosis, and restricted eye movements.4 The onset of NXG most commonly is seen in middle age.

Characteristic systemic associations have been reported in the setting of NXG. More than 20% of patients may exhibit hepatomegaly. Hematologic abnormalities, hyperlipidemia, and cryoglobulinemia also may be seen.1 In addition, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance is found in more than 80% of NXG cases. The IgG κ light chain is most commonly identified.2 A foreign body reaction is incited by the immunoglobulin-lipid complex, which is thought to contribute to the formation of cutaneous lesions. There may be associated plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or B-cell lymphoma in approximately 13% of cases.2 Evaluation for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder should be performed regularly with serum protein electrophoresis or immunofixation electrophoresis, and in some cases full-body imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted.1

Treatment of NXG often is unsuccessful. Surgical excision, systemic immunosuppressive agents, electron beam radiation, and destructive therapies such as cryotherapy may be trialed, often with little success.1 Cutaneous regression has been reported with combination treatment of high-dose dexamethasone and high-dose lenalidomide.5

- Efebera Y, Blanchard E, Allam C, et al. Complete response to thalidomide and dexamethasone in a patient with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:298-302.

- Koch PS, Goerdt S, Géraud C. Erythematous papules, plaques, and nodular lesions on the trunk and within preexisting scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1103-1104.

- Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: a review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:457-463.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Dholaria BR, Cappel M, Roy V. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: successful treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone [published online Jan 27, 2016]. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:671-672.

The Diagnosis: Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed for routine stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, xanthoma disseminatum, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure). There were surrounding areas of degenerated collagen containing numerous cholesterol clefts. After clinical pathologic correlation, a diagnosis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) was elucidated.

The patient was referred to general surgery for elective excision of 1 or more of the lesions. Excision of an abdominal lesion was performed without complication. After several months, a new lesion reformed within the excisional scar that also was consistent with NXG. At further dermatologic visits, a trial of intralesional corticosteroids was attempted to the largest lesions with modest improvement. In addition, follow-up with hematology and oncology was recommended for routine surveillance of the known blood dyscrasia.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a multisystem non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disease. Clinically, NXG is characterized by infiltrative plaques and ulcerative nodules. Lesions may appear red, brown, or yellow with associated atrophy and telangiectasia.1 Koch et al2 described a predilection for granuloma formation within preexisting scars. Periorbital location is the most common cutaneous site of involvement of NXG, seen in 80% of cases, but the trunk and extremities also may be involved.1,3 Approximately half of those with periocular involvement experience ocular symptoms including prop- tosis, blepharoptosis, and restricted eye movements.4 The onset of NXG most commonly is seen in middle age.

Characteristic systemic associations have been reported in the setting of NXG. More than 20% of patients may exhibit hepatomegaly. Hematologic abnormalities, hyperlipidemia, and cryoglobulinemia also may be seen.1 In addition, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance is found in more than 80% of NXG cases. The IgG κ light chain is most commonly identified.2 A foreign body reaction is incited by the immunoglobulin-lipid complex, which is thought to contribute to the formation of cutaneous lesions. There may be associated plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or B-cell lymphoma in approximately 13% of cases.2 Evaluation for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder should be performed regularly with serum protein electrophoresis or immunofixation electrophoresis, and in some cases full-body imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted.1

Treatment of NXG often is unsuccessful. Surgical excision, systemic immunosuppressive agents, electron beam radiation, and destructive therapies such as cryotherapy may be trialed, often with little success.1 Cutaneous regression has been reported with combination treatment of high-dose dexamethasone and high-dose lenalidomide.5

The Diagnosis: Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed for routine stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, xanthoma disseminatum, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure). There were surrounding areas of degenerated collagen containing numerous cholesterol clefts. After clinical pathologic correlation, a diagnosis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) was elucidated.

The patient was referred to general surgery for elective excision of 1 or more of the lesions. Excision of an abdominal lesion was performed without complication. After several months, a new lesion reformed within the excisional scar that also was consistent with NXG. At further dermatologic visits, a trial of intralesional corticosteroids was attempted to the largest lesions with modest improvement. In addition, follow-up with hematology and oncology was recommended for routine surveillance of the known blood dyscrasia.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a multisystem non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disease. Clinically, NXG is characterized by infiltrative plaques and ulcerative nodules. Lesions may appear red, brown, or yellow with associated atrophy and telangiectasia.1 Koch et al2 described a predilection for granuloma formation within preexisting scars. Periorbital location is the most common cutaneous site of involvement of NXG, seen in 80% of cases, but the trunk and extremities also may be involved.1,3 Approximately half of those with periocular involvement experience ocular symptoms including prop- tosis, blepharoptosis, and restricted eye movements.4 The onset of NXG most commonly is seen in middle age.

Characteristic systemic associations have been reported in the setting of NXG. More than 20% of patients may exhibit hepatomegaly. Hematologic abnormalities, hyperlipidemia, and cryoglobulinemia also may be seen.1 In addition, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance is found in more than 80% of NXG cases. The IgG κ light chain is most commonly identified.2 A foreign body reaction is incited by the immunoglobulin-lipid complex, which is thought to contribute to the formation of cutaneous lesions. There may be associated plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or B-cell lymphoma in approximately 13% of cases.2 Evaluation for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder should be performed regularly with serum protein electrophoresis or immunofixation electrophoresis, and in some cases full-body imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted.1

Treatment of NXG often is unsuccessful. Surgical excision, systemic immunosuppressive agents, electron beam radiation, and destructive therapies such as cryotherapy may be trialed, often with little success.1 Cutaneous regression has been reported with combination treatment of high-dose dexamethasone and high-dose lenalidomide.5

- Efebera Y, Blanchard E, Allam C, et al. Complete response to thalidomide and dexamethasone in a patient with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:298-302.

- Koch PS, Goerdt S, Géraud C. Erythematous papules, plaques, and nodular lesions on the trunk and within preexisting scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1103-1104.

- Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: a review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:457-463.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Dholaria BR, Cappel M, Roy V. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: successful treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone [published online Jan 27, 2016]. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:671-672.

- Efebera Y, Blanchard E, Allam C, et al. Complete response to thalidomide and dexamethasone in a patient with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:298-302.

- Koch PS, Goerdt S, Géraud C. Erythematous papules, plaques, and nodular lesions on the trunk and within preexisting scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1103-1104.

- Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: a review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:457-463.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Dholaria BR, Cappel M, Roy V. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: successful treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone [published online Jan 27, 2016]. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:671-672.

A 40-year-old man presented with tender lesions on the back, abdomen, and thighs of 10 years' duration. His medical history was remarkable for follicular lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance diagnosed 5 years after the onset of skin symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous irregularly shaped, yellow plaques on the back, abdomen, and thighs with overlying telangiectasia. A single lesion was noted to extend from a scar.