User login

In the Literature

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies.

- Physiologic doses of corticosteroids provide no clear benefit to patients with septic shock.

- Endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms is associated with fewer short-term deaths but complications and higher late reinterventions.

- Neither intensive insulin nor use of colloid over crystalloid improves mortality or organ failure outcomes in sepsis.

- Surgical cure for diabetes shows promise at two-year follow-up.

- Delayed defibrillation negatively affects survival.

- Right-ventricular enlargement in patients with acute PE is not associated with increased mortality.

- Periprocedural interruption of warfarin therapy presents low risk of thromboembolism.

- Minor leg injury increases risk of developing venous thrombosis threefold.

- Oral vs. parenteral antibiotics for pediatric pyelonephritis.

Do Physiologic Doses of Hydrocortisone Benefit Patients With Septic Shock?

Background: Meta-analyses and guidelines advocate the use of physiologic dose steroids in patients exhibiting septic shock. However, recommendations are largely based on the results of a single trial where benefits were seen only in patients without a response to corticotropin.

Study design: Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Setting: Fifty-two participating ICUs in nine countries.

Synopsis: A total of 499 patients with evidence of infection or a systemic inflammatory response characterized by refractory hypotension were randomly selected to receive either an 11-day tapering dose of hydrocortisone or a placebo. The primary outcome was death from any cause at 28 days. A corticotropin stimulation test was conducted on every patient to assess adrenal function. There were no differences in death rates or duration of hospitalization between study arms. Overall, there were 86 deaths in the hydrocortisone group and 78 deaths in the placebo group (p=0.51). Also, response to corticotropin appeared to have little bearing on outcomes.

The study was underpowered due to low enrollment and a lower-than-expected death rate. Nevertheless, this is the largest trial to date examining the role of steroids in the management of septic shock and calls into question the strength of prior data and published guidelines.

Bottom line: This study failed to demonstrate a clinically or statistically significant treatment effect from the administration of physiologic-dose steroids in patients with septic shock.

Citation: Sprung C, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):111-124.

Does Open or Endovascular Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Benefit the Medicare Population?

Background: Randomized controlled trials (RCT) have shown a perioperative survival benefit of endovascular repair over open repair with fewer complications and shorter recovery. There is concern that late morbidity may be increased with endovascular repair. Patients enrolled in the trials were highly selected at specialty centers, so the results may not reflect actual practice.

Study design: Retrospective, propensity-matched, observational cohort study.

Synopsis: 22,830 patients were matched in each cohort. Patients were eligible if they had an abdominal aortic aneurysm repair without rupture and excluded if they were enrolled in health maintenance organizations.

Outcomes included death within 30 days and late survival, perioperative complications, aneurysm rupture, reintervention, and laparotomy-related complications. The average age was 76, and 20% were women. Perioperative mortality was lower after endovascular repair (1.2% vs. 4.8%, p<0.001), and older patients had a greater benefit. Late survival was similar. By four years, rupture was more likely in the endovascular group (1.8% vs. 0.5%, p<0.001), as was reintervention (9% vs. 1.7%, p<0.001).

In contrast, by four years, surgery for laparotomy-related complications was more likely in the open-repair group (9.7% v 4.1%, p<0.001), as was hospitalization for bowel obstruction or abdominal-wall hernia (14.2% v 8.1%, p<0.001). Limitations included the non-randomized design and use of administrative data for important categorical variables including medical co-morbidities.

Bottom line: As compared with open repair, endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with lower short-term death and complications and higher late reinterventions. This is balanced by an increase in laparotomy-related reinterventions after open repair.

Citation: Schermerhorn ML, O’Malley AJ, Jhaveri A, Cotterill P, Pomposelli F, Landon BE. Endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 31;358(5):464-474.

What Therapy Improves Outcomes in ICU Patients With Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock?

Background: Evidence suggests lower mortality with intensive insulin therapy in post-surgical cardiac patients. There is no proven benefit for non-surgical ICU patients. Despite lack of data, intensive insulin in severe sepsis has been widely advocated. Little is known to guide the use of colloid or crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in sepsis.

Study design: Multicenter, two-by-two factorial, open-label trial.

Setting: Multidisciplinary ICUs at 18 academic tertiary hospitals in Germany.

Synopsis: Data were analyzed for 537 patients with severe sepsis. They were randomly selected to receive intensive insulin therapy (n=247) or conventional insulin therapy (290), with either 10% hydroxyethyl starch (HES) (262) or modified Ringer’s lactate (LR) (275) for fluid resuscitation.

Co-primary endpoints were all-cause mortality at 28 days and morbidity as measured by the mean score on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA). The trial was stopped early for safety reasons. Intensive insulin therapy was terminated due to an increased number of hypoglycemic events in the intensive-therapy group compared with conventional therapy (12.1% vs. 2.1%, p<0.001), and there was no difference in mortality between groups at 28 and 90 days.

Interim analysis of 600 patients showed patients given HES had higher incidence of renal failure compared with LR (34.9% vs. 22.8%, p=0.002), required more days of renal replacement therapy, had lower median platelets and received more units of packed red cells. There was a trend toward higher rate of death at 90 days in those treated with HES (41% vs. 33.9%, p=0.09).

Bottom line: Intensive insulin therapy in ICU patients with severe sepsis and septic shock does not improve mortality and increases hypoglycemia and ICU length of stay. Use of colloid over crystalloid should be avoided, showing a trend toward increased death at 90 days, higher rates of acute renal failure, and need for renal replacement therapy..

Citation: Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):125-139.

How Does Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding Affect Obese Adults With Type 2 Diabetes?

Background: Observational studies related surgical weight loss to improved glycemic control, but clinical trials did not test this relationship. The current trial examined this hypothesis.

Study design: Unmasked, randomized controlled trial.

Setting: University Obesity Research Center, Australia.

Synopsis: Sixty adults age 20-60 with body-mass index (BMI) of 30-40 and diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2) within two years of recruitment were randomized into conventional therapy and surgical groups.

While both groups were treated similarly, only the surgical group received laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Primary outcome was remission of DM2 (a fasting glucose less than 126 mg/dl, HbA1C less than 6.2%, and off all hypoglycemic agents). At two years, 73% in the surgical group compared with 13% in the conventional group attained this outcome (relative risk [RR] 5.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2-14.0; p<0.001). Compared with the conventional group, the surgical group demonstrated statistically significant improvements in several secondary outcomes including mean body weight, waist circumference, insulin resistance, and lipids.

The limitations of the study are that it examined a small number of patients with shorter duration of DM2 and a shorter follow-up. The lower surgical complication rates cannot be generalized to other centers.

Bottom line: This study is a step forward in examining the relationship of surgical weight loss and remission of DM2. However, large multicenter trials with longer periods of follow-up in diverse group of patients would result in a better understanding of this relationship.

Citation: Dixon JB, O’Brien PE, Playfair J, et. al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(3):316-323.

What is the Prevalence of Delayed Defibrillation and its Association With Survival to Discharge?

Background: Despite advances in resuscitation, survival rates following cardiac arrest remain low. Previous studies observed the effect of the timing of defibrillation on survival. This study examined the magnitude of delayed defibrillation and its association with survival in adults who sustained cardiac arrest specifically from ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

Study design: National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR), a multicenter prospective cohort.

Setting: 369 U.S. hospitals providing acute care.

Synopsis: Data from NRCPR relating to 6,789 cardiac arrests secondary to ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia, at 369 hospitals in hospitalized adults were analyzed. Delayed defibrillation was defined as occurring more than two minutes from the identification of ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia to the administration of the first shock to the patient.

Delayed defibrillation occurred in 2,045 (30.1%) subjects. A lower proportion of subjects who received delayed defibrillation (22.2%) compared with those who received defibrillation in two minutes or less (39.3%) survived to hospital discharge. This was statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.48, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.54; p<0.01).

Bottom line: This study not only reported that delayed defibrillation was prevalent in adult hospitalized patients, but also reinforced the importance of defibrillation within two minutes of identification of cardiac arrest secondary to ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia for better survival outcomes.

Citation: Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):9-17.

Does Right-Ventricle Enlargement in Acute PE Increase In-hospital Death From PE or All-cause Mortality?

Background: Previous studies have shown conflicting results regarding the risk of death with right-ventricular enlargement in acute pulmonary embolism (PE). The role of thrombolysis in hemodynamically stable patients with acute PE and right-ventricular enlargement remains controversial.

Study design: Retrospective analysis of prospective cohort study.

Setting: Academic centers housing inpatients and outpatients in the United States and Canada.

Synopsis: Patients enrolled in PIOPED II who were diagnosed with acute PE and had multidetector computed tomographic (CT) angiography were retrospectively reviewed for the presence of right-ventricular enlargement. Study determined that 181 patients had PE and a CT, and 157 were adequate for measurement of right-ventricular size. PE treatment was anticoagulation in 138, anticoagulation and inferior vena cava filter in 15, inferior vena cava filter alone in two, and thrombolysis in two.

Right-ventricular enlargement was found in 78 (50%) patients; 76 were treated with anticoagulation alone or in combination with inferior vena cava filter. For patients with and without right-ventricular enlargement, there was no difference in in-hospital death from PE (0% vs. 1.3%) or all-cause mortality (2.6% vs. 2.5%). The results were unchanged when examined for septal motion abnormality and previous cardiopulmonary disease.

Bottom line: In hemodynamically stable patients with acute pulmonary embolism, right ventricular enlargement does not increase mortality. Further, thrombolytic therapy is unlikely to improve outcomes.

Citation: Stein PD, Beemath A, Matti F, et al. Enlarged right ventricle without shock in acute pulmonary embolus: prognosis. Am J Med. 2008;121:34-42.

What Are Short-term Thromboembolism, Hemorrhage Risks When Interrupting Warfarin Therapy for Procedures?

Background: The risks of thromboembolism and hemorrhage during the periprocedural interruption of warfarin therapy are not known. The risks and benefits of heparin bridging therapy are not well described.

Study design: Multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: Community-based physician practices.

Synopsis: Patients were eligible if they were on long-term warfarin and underwent outpatient procedures requiring interruption of therapy. The primary outcomes were thromboembolism or hemorrhage within 30 days of therapy interruption. In all, 1,024 eligible patients (7.1% considered high risk) had 1,293 interruptions of warfarin therapy. The most common procedures were colonoscopy (25.1%), oral or dental surgery (24.9%), and ophthalmologic surgery (8.9%). Warfarin interruption was five or fewer days in 83.8% of episodes.

Thromboembolism occurred in seven (0.7%) patients, and major or clinically significant bleeding occurred in 23 (0.6%, and 1.7%, respectively) patients. Periprocedural bridging with heparin was used in 88 (8.6%) patients. Of the patients who received periprocedural heparin therapy, none had thromboembolism, and 14 (13%) had bleeding episodes.

Bottom line: In patients whose warfarin therapy is interrupted to undergo outpatient procedures, the risk of thromboembolism is low and the hemorrhagic risk of heparin bridging therapy is significant.

Citation: Garcia DA, Regan S, Henault LE, et al. Risk of thromboembolism with short-term interruption of warfarin therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):63-69.

Are Minor Injuries an Independent Risk Factor For Development of DVT?

Background: Prior studies focus on major injuries as a risk factor for deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) and PE. However, major injury is often associated with other risks for venous thrombosis, such as surgery, plaster casting, hospitalization, and extended bed rest. Risk of DVT with minor injuries that don’t lead to these factors is unknown.

Study design: Large population-based case-control study.

Setting: Six anticoagulation clinics in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: 2,471 consecutive cases (patients with first episode of DVT or PE) and 3,534 controls (partners of cases or random digit dialing contacts) were enrolled. Participants were mailed a questionnaire, including a list of eight common injuries.

Participants with history of cast, surgery, recent hospitalization, extended bed rest, or prior history of cancer were excluded. A subset of patients and controls underwent DNA and blood collection to evaluate for presence of a hypercoagulable state. Of the cases, 289 (11.7%) had a minor injury within three months of the index date, compared with 154 (4.4%) of controls, representing a threefold increased risk of DVT/PE with minor injury (OR 3.1). Partial ruptures of muscles or ligaments in the leg (OR 10.9), multiple simultaneous injuries (OR 9.9), and injury within four weeks of presentation (OR 4.0), were associated with increased risk of DVT/PE.

Patients found to be Factor V Leiden carriers with injury had an almost 50-fold increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared with non-carriers without injury (OR 49.7). Authors appropriately address possible limitations, including recall and referral bias.

Bottom line: Minor leg injury is associated with threefold risk of DVT/PE, especially in the four weeks following injury. Providers should consider short-term prophylactic treatment in patients with Factor V Leiden or high-risk injuries.

Citation: Van Stralen KJ, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. Minor injuries as a risk factor for venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):21-26.

Is Oral Amox-Clav Non-inferior to IV Antibiotics in Pediatric Pyelonephritis?

Background: Present guidelines recommend initial treatment for pediatric pyelonephritis to be a parenteral third-generation cephalosporin followed by oral antibiotics. One prior randomly selected controlled trial compared oral antibiotics only with antibiotics started parenterally, but there was a higher-than-usual incidence of vesicoureteral reflux and female gender in the study.

Study design: Non-inferiority, multicenter, random, open label, controlled trial.

Setting: Twenty-eight pediatric units in northeast Italy from 2000-2005

Synopsis: 502 children age 1 month to less than 7 years with a clinical diagnosis of first occurrence of acute pyelonephritis according to urinalysis and urine culture (requiring two concordant consecutive tests) with at least two of the following conditions: fever of 38 degrees C or more or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or c-reactive protein (CRP), and elevated neutrophil count were randomized to receive oral amoxicillin-clavulanate (AC) or parenteral ceftriaxone followed by oral AC. Exclusion criteria were sepsis, dehydration, vomiting, and creatinine clearance of 70 ml/min or less.

Also, 400 children had dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scintigraphy within 10 days of study entry. Meantime, 223 had repeat DMSA at one year, and 177 had normal scans at study entry so were not repeated. At one year, 20% of patients were lost to follow-up. The primary outcome was renal scarring at one year. Secondary outcomes included time to fever defervescence, reduction in inflammatory indices, and percentage with sterile urine after 72 hours. Intention to treat analysis showed no significant differences between oral (n=244) and parenteral (n=258) treatment, both in the primary outcome 13.7% vs. 17.7% (95% CI, -11.1% to 3.1%), and secondary outcomes.

Bottom line: Treatment with oral antibiotics is as effective as parenteral then oral treatment for first episode of acute pediatric pyelonephritis.

Citation: Montini G, Toffolo A, Zucchetta P, et al. Antibiotic treatment for pyelonephritis in children: multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2007 Aug 25;335(7616):386.

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies.

- Physiologic doses of corticosteroids provide no clear benefit to patients with septic shock.

- Endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms is associated with fewer short-term deaths but complications and higher late reinterventions.

- Neither intensive insulin nor use of colloid over crystalloid improves mortality or organ failure outcomes in sepsis.

- Surgical cure for diabetes shows promise at two-year follow-up.

- Delayed defibrillation negatively affects survival.

- Right-ventricular enlargement in patients with acute PE is not associated with increased mortality.

- Periprocedural interruption of warfarin therapy presents low risk of thromboembolism.

- Minor leg injury increases risk of developing venous thrombosis threefold.

- Oral vs. parenteral antibiotics for pediatric pyelonephritis.

Do Physiologic Doses of Hydrocortisone Benefit Patients With Septic Shock?

Background: Meta-analyses and guidelines advocate the use of physiologic dose steroids in patients exhibiting septic shock. However, recommendations are largely based on the results of a single trial where benefits were seen only in patients without a response to corticotropin.

Study design: Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Setting: Fifty-two participating ICUs in nine countries.

Synopsis: A total of 499 patients with evidence of infection or a systemic inflammatory response characterized by refractory hypotension were randomly selected to receive either an 11-day tapering dose of hydrocortisone or a placebo. The primary outcome was death from any cause at 28 days. A corticotropin stimulation test was conducted on every patient to assess adrenal function. There were no differences in death rates or duration of hospitalization between study arms. Overall, there were 86 deaths in the hydrocortisone group and 78 deaths in the placebo group (p=0.51). Also, response to corticotropin appeared to have little bearing on outcomes.

The study was underpowered due to low enrollment and a lower-than-expected death rate. Nevertheless, this is the largest trial to date examining the role of steroids in the management of septic shock and calls into question the strength of prior data and published guidelines.

Bottom line: This study failed to demonstrate a clinically or statistically significant treatment effect from the administration of physiologic-dose steroids in patients with septic shock.

Citation: Sprung C, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):111-124.

Does Open or Endovascular Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Benefit the Medicare Population?

Background: Randomized controlled trials (RCT) have shown a perioperative survival benefit of endovascular repair over open repair with fewer complications and shorter recovery. There is concern that late morbidity may be increased with endovascular repair. Patients enrolled in the trials were highly selected at specialty centers, so the results may not reflect actual practice.

Study design: Retrospective, propensity-matched, observational cohort study.

Synopsis: 22,830 patients were matched in each cohort. Patients were eligible if they had an abdominal aortic aneurysm repair without rupture and excluded if they were enrolled in health maintenance organizations.

Outcomes included death within 30 days and late survival, perioperative complications, aneurysm rupture, reintervention, and laparotomy-related complications. The average age was 76, and 20% were women. Perioperative mortality was lower after endovascular repair (1.2% vs. 4.8%, p<0.001), and older patients had a greater benefit. Late survival was similar. By four years, rupture was more likely in the endovascular group (1.8% vs. 0.5%, p<0.001), as was reintervention (9% vs. 1.7%, p<0.001).

In contrast, by four years, surgery for laparotomy-related complications was more likely in the open-repair group (9.7% v 4.1%, p<0.001), as was hospitalization for bowel obstruction or abdominal-wall hernia (14.2% v 8.1%, p<0.001). Limitations included the non-randomized design and use of administrative data for important categorical variables including medical co-morbidities.

Bottom line: As compared with open repair, endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with lower short-term death and complications and higher late reinterventions. This is balanced by an increase in laparotomy-related reinterventions after open repair.

Citation: Schermerhorn ML, O’Malley AJ, Jhaveri A, Cotterill P, Pomposelli F, Landon BE. Endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 31;358(5):464-474.

What Therapy Improves Outcomes in ICU Patients With Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock?

Background: Evidence suggests lower mortality with intensive insulin therapy in post-surgical cardiac patients. There is no proven benefit for non-surgical ICU patients. Despite lack of data, intensive insulin in severe sepsis has been widely advocated. Little is known to guide the use of colloid or crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in sepsis.

Study design: Multicenter, two-by-two factorial, open-label trial.

Setting: Multidisciplinary ICUs at 18 academic tertiary hospitals in Germany.

Synopsis: Data were analyzed for 537 patients with severe sepsis. They were randomly selected to receive intensive insulin therapy (n=247) or conventional insulin therapy (290), with either 10% hydroxyethyl starch (HES) (262) or modified Ringer’s lactate (LR) (275) for fluid resuscitation.

Co-primary endpoints were all-cause mortality at 28 days and morbidity as measured by the mean score on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA). The trial was stopped early for safety reasons. Intensive insulin therapy was terminated due to an increased number of hypoglycemic events in the intensive-therapy group compared with conventional therapy (12.1% vs. 2.1%, p<0.001), and there was no difference in mortality between groups at 28 and 90 days.

Interim analysis of 600 patients showed patients given HES had higher incidence of renal failure compared with LR (34.9% vs. 22.8%, p=0.002), required more days of renal replacement therapy, had lower median platelets and received more units of packed red cells. There was a trend toward higher rate of death at 90 days in those treated with HES (41% vs. 33.9%, p=0.09).

Bottom line: Intensive insulin therapy in ICU patients with severe sepsis and septic shock does not improve mortality and increases hypoglycemia and ICU length of stay. Use of colloid over crystalloid should be avoided, showing a trend toward increased death at 90 days, higher rates of acute renal failure, and need for renal replacement therapy..

Citation: Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):125-139.

How Does Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding Affect Obese Adults With Type 2 Diabetes?

Background: Observational studies related surgical weight loss to improved glycemic control, but clinical trials did not test this relationship. The current trial examined this hypothesis.

Study design: Unmasked, randomized controlled trial.

Setting: University Obesity Research Center, Australia.

Synopsis: Sixty adults age 20-60 with body-mass index (BMI) of 30-40 and diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2) within two years of recruitment were randomized into conventional therapy and surgical groups.

While both groups were treated similarly, only the surgical group received laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Primary outcome was remission of DM2 (a fasting glucose less than 126 mg/dl, HbA1C less than 6.2%, and off all hypoglycemic agents). At two years, 73% in the surgical group compared with 13% in the conventional group attained this outcome (relative risk [RR] 5.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2-14.0; p<0.001). Compared with the conventional group, the surgical group demonstrated statistically significant improvements in several secondary outcomes including mean body weight, waist circumference, insulin resistance, and lipids.

The limitations of the study are that it examined a small number of patients with shorter duration of DM2 and a shorter follow-up. The lower surgical complication rates cannot be generalized to other centers.

Bottom line: This study is a step forward in examining the relationship of surgical weight loss and remission of DM2. However, large multicenter trials with longer periods of follow-up in diverse group of patients would result in a better understanding of this relationship.

Citation: Dixon JB, O’Brien PE, Playfair J, et. al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(3):316-323.

What is the Prevalence of Delayed Defibrillation and its Association With Survival to Discharge?

Background: Despite advances in resuscitation, survival rates following cardiac arrest remain low. Previous studies observed the effect of the timing of defibrillation on survival. This study examined the magnitude of delayed defibrillation and its association with survival in adults who sustained cardiac arrest specifically from ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

Study design: National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR), a multicenter prospective cohort.

Setting: 369 U.S. hospitals providing acute care.

Synopsis: Data from NRCPR relating to 6,789 cardiac arrests secondary to ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia, at 369 hospitals in hospitalized adults were analyzed. Delayed defibrillation was defined as occurring more than two minutes from the identification of ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia to the administration of the first shock to the patient.

Delayed defibrillation occurred in 2,045 (30.1%) subjects. A lower proportion of subjects who received delayed defibrillation (22.2%) compared with those who received defibrillation in two minutes or less (39.3%) survived to hospital discharge. This was statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.48, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.54; p<0.01).

Bottom line: This study not only reported that delayed defibrillation was prevalent in adult hospitalized patients, but also reinforced the importance of defibrillation within two minutes of identification of cardiac arrest secondary to ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia for better survival outcomes.

Citation: Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):9-17.

Does Right-Ventricle Enlargement in Acute PE Increase In-hospital Death From PE or All-cause Mortality?

Background: Previous studies have shown conflicting results regarding the risk of death with right-ventricular enlargement in acute pulmonary embolism (PE). The role of thrombolysis in hemodynamically stable patients with acute PE and right-ventricular enlargement remains controversial.

Study design: Retrospective analysis of prospective cohort study.

Setting: Academic centers housing inpatients and outpatients in the United States and Canada.

Synopsis: Patients enrolled in PIOPED II who were diagnosed with acute PE and had multidetector computed tomographic (CT) angiography were retrospectively reviewed for the presence of right-ventricular enlargement. Study determined that 181 patients had PE and a CT, and 157 were adequate for measurement of right-ventricular size. PE treatment was anticoagulation in 138, anticoagulation and inferior vena cava filter in 15, inferior vena cava filter alone in two, and thrombolysis in two.

Right-ventricular enlargement was found in 78 (50%) patients; 76 were treated with anticoagulation alone or in combination with inferior vena cava filter. For patients with and without right-ventricular enlargement, there was no difference in in-hospital death from PE (0% vs. 1.3%) or all-cause mortality (2.6% vs. 2.5%). The results were unchanged when examined for septal motion abnormality and previous cardiopulmonary disease.

Bottom line: In hemodynamically stable patients with acute pulmonary embolism, right ventricular enlargement does not increase mortality. Further, thrombolytic therapy is unlikely to improve outcomes.

Citation: Stein PD, Beemath A, Matti F, et al. Enlarged right ventricle without shock in acute pulmonary embolus: prognosis. Am J Med. 2008;121:34-42.

What Are Short-term Thromboembolism, Hemorrhage Risks When Interrupting Warfarin Therapy for Procedures?

Background: The risks of thromboembolism and hemorrhage during the periprocedural interruption of warfarin therapy are not known. The risks and benefits of heparin bridging therapy are not well described.

Study design: Multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: Community-based physician practices.

Synopsis: Patients were eligible if they were on long-term warfarin and underwent outpatient procedures requiring interruption of therapy. The primary outcomes were thromboembolism or hemorrhage within 30 days of therapy interruption. In all, 1,024 eligible patients (7.1% considered high risk) had 1,293 interruptions of warfarin therapy. The most common procedures were colonoscopy (25.1%), oral or dental surgery (24.9%), and ophthalmologic surgery (8.9%). Warfarin interruption was five or fewer days in 83.8% of episodes.

Thromboembolism occurred in seven (0.7%) patients, and major or clinically significant bleeding occurred in 23 (0.6%, and 1.7%, respectively) patients. Periprocedural bridging with heparin was used in 88 (8.6%) patients. Of the patients who received periprocedural heparin therapy, none had thromboembolism, and 14 (13%) had bleeding episodes.

Bottom line: In patients whose warfarin therapy is interrupted to undergo outpatient procedures, the risk of thromboembolism is low and the hemorrhagic risk of heparin bridging therapy is significant.

Citation: Garcia DA, Regan S, Henault LE, et al. Risk of thromboembolism with short-term interruption of warfarin therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):63-69.

Are Minor Injuries an Independent Risk Factor For Development of DVT?

Background: Prior studies focus on major injuries as a risk factor for deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) and PE. However, major injury is often associated with other risks for venous thrombosis, such as surgery, plaster casting, hospitalization, and extended bed rest. Risk of DVT with minor injuries that don’t lead to these factors is unknown.

Study design: Large population-based case-control study.

Setting: Six anticoagulation clinics in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: 2,471 consecutive cases (patients with first episode of DVT or PE) and 3,534 controls (partners of cases or random digit dialing contacts) were enrolled. Participants were mailed a questionnaire, including a list of eight common injuries.

Participants with history of cast, surgery, recent hospitalization, extended bed rest, or prior history of cancer were excluded. A subset of patients and controls underwent DNA and blood collection to evaluate for presence of a hypercoagulable state. Of the cases, 289 (11.7%) had a minor injury within three months of the index date, compared with 154 (4.4%) of controls, representing a threefold increased risk of DVT/PE with minor injury (OR 3.1). Partial ruptures of muscles or ligaments in the leg (OR 10.9), multiple simultaneous injuries (OR 9.9), and injury within four weeks of presentation (OR 4.0), were associated with increased risk of DVT/PE.

Patients found to be Factor V Leiden carriers with injury had an almost 50-fold increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared with non-carriers without injury (OR 49.7). Authors appropriately address possible limitations, including recall and referral bias.

Bottom line: Minor leg injury is associated with threefold risk of DVT/PE, especially in the four weeks following injury. Providers should consider short-term prophylactic treatment in patients with Factor V Leiden or high-risk injuries.

Citation: Van Stralen KJ, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. Minor injuries as a risk factor for venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):21-26.

Is Oral Amox-Clav Non-inferior to IV Antibiotics in Pediatric Pyelonephritis?

Background: Present guidelines recommend initial treatment for pediatric pyelonephritis to be a parenteral third-generation cephalosporin followed by oral antibiotics. One prior randomly selected controlled trial compared oral antibiotics only with antibiotics started parenterally, but there was a higher-than-usual incidence of vesicoureteral reflux and female gender in the study.

Study design: Non-inferiority, multicenter, random, open label, controlled trial.

Setting: Twenty-eight pediatric units in northeast Italy from 2000-2005

Synopsis: 502 children age 1 month to less than 7 years with a clinical diagnosis of first occurrence of acute pyelonephritis according to urinalysis and urine culture (requiring two concordant consecutive tests) with at least two of the following conditions: fever of 38 degrees C or more or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or c-reactive protein (CRP), and elevated neutrophil count were randomized to receive oral amoxicillin-clavulanate (AC) or parenteral ceftriaxone followed by oral AC. Exclusion criteria were sepsis, dehydration, vomiting, and creatinine clearance of 70 ml/min or less.

Also, 400 children had dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scintigraphy within 10 days of study entry. Meantime, 223 had repeat DMSA at one year, and 177 had normal scans at study entry so were not repeated. At one year, 20% of patients were lost to follow-up. The primary outcome was renal scarring at one year. Secondary outcomes included time to fever defervescence, reduction in inflammatory indices, and percentage with sterile urine after 72 hours. Intention to treat analysis showed no significant differences between oral (n=244) and parenteral (n=258) treatment, both in the primary outcome 13.7% vs. 17.7% (95% CI, -11.1% to 3.1%), and secondary outcomes.

Bottom line: Treatment with oral antibiotics is as effective as parenteral then oral treatment for first episode of acute pediatric pyelonephritis.

Citation: Montini G, Toffolo A, Zucchetta P, et al. Antibiotic treatment for pyelonephritis in children: multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2007 Aug 25;335(7616):386.

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies.

- Physiologic doses of corticosteroids provide no clear benefit to patients with septic shock.

- Endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms is associated with fewer short-term deaths but complications and higher late reinterventions.

- Neither intensive insulin nor use of colloid over crystalloid improves mortality or organ failure outcomes in sepsis.

- Surgical cure for diabetes shows promise at two-year follow-up.

- Delayed defibrillation negatively affects survival.

- Right-ventricular enlargement in patients with acute PE is not associated with increased mortality.

- Periprocedural interruption of warfarin therapy presents low risk of thromboembolism.

- Minor leg injury increases risk of developing venous thrombosis threefold.

- Oral vs. parenteral antibiotics for pediatric pyelonephritis.

Do Physiologic Doses of Hydrocortisone Benefit Patients With Septic Shock?

Background: Meta-analyses and guidelines advocate the use of physiologic dose steroids in patients exhibiting septic shock. However, recommendations are largely based on the results of a single trial where benefits were seen only in patients without a response to corticotropin.

Study design: Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Setting: Fifty-two participating ICUs in nine countries.

Synopsis: A total of 499 patients with evidence of infection or a systemic inflammatory response characterized by refractory hypotension were randomly selected to receive either an 11-day tapering dose of hydrocortisone or a placebo. The primary outcome was death from any cause at 28 days. A corticotropin stimulation test was conducted on every patient to assess adrenal function. There were no differences in death rates or duration of hospitalization between study arms. Overall, there were 86 deaths in the hydrocortisone group and 78 deaths in the placebo group (p=0.51). Also, response to corticotropin appeared to have little bearing on outcomes.

The study was underpowered due to low enrollment and a lower-than-expected death rate. Nevertheless, this is the largest trial to date examining the role of steroids in the management of septic shock and calls into question the strength of prior data and published guidelines.

Bottom line: This study failed to demonstrate a clinically or statistically significant treatment effect from the administration of physiologic-dose steroids in patients with septic shock.

Citation: Sprung C, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):111-124.

Does Open or Endovascular Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Benefit the Medicare Population?

Background: Randomized controlled trials (RCT) have shown a perioperative survival benefit of endovascular repair over open repair with fewer complications and shorter recovery. There is concern that late morbidity may be increased with endovascular repair. Patients enrolled in the trials were highly selected at specialty centers, so the results may not reflect actual practice.

Study design: Retrospective, propensity-matched, observational cohort study.

Synopsis: 22,830 patients were matched in each cohort. Patients were eligible if they had an abdominal aortic aneurysm repair without rupture and excluded if they were enrolled in health maintenance organizations.

Outcomes included death within 30 days and late survival, perioperative complications, aneurysm rupture, reintervention, and laparotomy-related complications. The average age was 76, and 20% were women. Perioperative mortality was lower after endovascular repair (1.2% vs. 4.8%, p<0.001), and older patients had a greater benefit. Late survival was similar. By four years, rupture was more likely in the endovascular group (1.8% vs. 0.5%, p<0.001), as was reintervention (9% vs. 1.7%, p<0.001).

In contrast, by four years, surgery for laparotomy-related complications was more likely in the open-repair group (9.7% v 4.1%, p<0.001), as was hospitalization for bowel obstruction or abdominal-wall hernia (14.2% v 8.1%, p<0.001). Limitations included the non-randomized design and use of administrative data for important categorical variables including medical co-morbidities.

Bottom line: As compared with open repair, endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with lower short-term death and complications and higher late reinterventions. This is balanced by an increase in laparotomy-related reinterventions after open repair.

Citation: Schermerhorn ML, O’Malley AJ, Jhaveri A, Cotterill P, Pomposelli F, Landon BE. Endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 31;358(5):464-474.

What Therapy Improves Outcomes in ICU Patients With Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock?

Background: Evidence suggests lower mortality with intensive insulin therapy in post-surgical cardiac patients. There is no proven benefit for non-surgical ICU patients. Despite lack of data, intensive insulin in severe sepsis has been widely advocated. Little is known to guide the use of colloid or crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in sepsis.

Study design: Multicenter, two-by-two factorial, open-label trial.

Setting: Multidisciplinary ICUs at 18 academic tertiary hospitals in Germany.

Synopsis: Data were analyzed for 537 patients with severe sepsis. They were randomly selected to receive intensive insulin therapy (n=247) or conventional insulin therapy (290), with either 10% hydroxyethyl starch (HES) (262) or modified Ringer’s lactate (LR) (275) for fluid resuscitation.

Co-primary endpoints were all-cause mortality at 28 days and morbidity as measured by the mean score on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA). The trial was stopped early for safety reasons. Intensive insulin therapy was terminated due to an increased number of hypoglycemic events in the intensive-therapy group compared with conventional therapy (12.1% vs. 2.1%, p<0.001), and there was no difference in mortality between groups at 28 and 90 days.

Interim analysis of 600 patients showed patients given HES had higher incidence of renal failure compared with LR (34.9% vs. 22.8%, p=0.002), required more days of renal replacement therapy, had lower median platelets and received more units of packed red cells. There was a trend toward higher rate of death at 90 days in those treated with HES (41% vs. 33.9%, p=0.09).

Bottom line: Intensive insulin therapy in ICU patients with severe sepsis and septic shock does not improve mortality and increases hypoglycemia and ICU length of stay. Use of colloid over crystalloid should be avoided, showing a trend toward increased death at 90 days, higher rates of acute renal failure, and need for renal replacement therapy..

Citation: Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):125-139.

How Does Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding Affect Obese Adults With Type 2 Diabetes?

Background: Observational studies related surgical weight loss to improved glycemic control, but clinical trials did not test this relationship. The current trial examined this hypothesis.

Study design: Unmasked, randomized controlled trial.

Setting: University Obesity Research Center, Australia.

Synopsis: Sixty adults age 20-60 with body-mass index (BMI) of 30-40 and diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2) within two years of recruitment were randomized into conventional therapy and surgical groups.

While both groups were treated similarly, only the surgical group received laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Primary outcome was remission of DM2 (a fasting glucose less than 126 mg/dl, HbA1C less than 6.2%, and off all hypoglycemic agents). At two years, 73% in the surgical group compared with 13% in the conventional group attained this outcome (relative risk [RR] 5.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2-14.0; p<0.001). Compared with the conventional group, the surgical group demonstrated statistically significant improvements in several secondary outcomes including mean body weight, waist circumference, insulin resistance, and lipids.

The limitations of the study are that it examined a small number of patients with shorter duration of DM2 and a shorter follow-up. The lower surgical complication rates cannot be generalized to other centers.

Bottom line: This study is a step forward in examining the relationship of surgical weight loss and remission of DM2. However, large multicenter trials with longer periods of follow-up in diverse group of patients would result in a better understanding of this relationship.

Citation: Dixon JB, O’Brien PE, Playfair J, et. al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(3):316-323.

What is the Prevalence of Delayed Defibrillation and its Association With Survival to Discharge?

Background: Despite advances in resuscitation, survival rates following cardiac arrest remain low. Previous studies observed the effect of the timing of defibrillation on survival. This study examined the magnitude of delayed defibrillation and its association with survival in adults who sustained cardiac arrest specifically from ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

Study design: National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR), a multicenter prospective cohort.

Setting: 369 U.S. hospitals providing acute care.

Synopsis: Data from NRCPR relating to 6,789 cardiac arrests secondary to ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia, at 369 hospitals in hospitalized adults were analyzed. Delayed defibrillation was defined as occurring more than two minutes from the identification of ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia to the administration of the first shock to the patient.

Delayed defibrillation occurred in 2,045 (30.1%) subjects. A lower proportion of subjects who received delayed defibrillation (22.2%) compared with those who received defibrillation in two minutes or less (39.3%) survived to hospital discharge. This was statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.48, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.54; p<0.01).

Bottom line: This study not only reported that delayed defibrillation was prevalent in adult hospitalized patients, but also reinforced the importance of defibrillation within two minutes of identification of cardiac arrest secondary to ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia for better survival outcomes.

Citation: Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):9-17.

Does Right-Ventricle Enlargement in Acute PE Increase In-hospital Death From PE or All-cause Mortality?

Background: Previous studies have shown conflicting results regarding the risk of death with right-ventricular enlargement in acute pulmonary embolism (PE). The role of thrombolysis in hemodynamically stable patients with acute PE and right-ventricular enlargement remains controversial.

Study design: Retrospective analysis of prospective cohort study.

Setting: Academic centers housing inpatients and outpatients in the United States and Canada.

Synopsis: Patients enrolled in PIOPED II who were diagnosed with acute PE and had multidetector computed tomographic (CT) angiography were retrospectively reviewed for the presence of right-ventricular enlargement. Study determined that 181 patients had PE and a CT, and 157 were adequate for measurement of right-ventricular size. PE treatment was anticoagulation in 138, anticoagulation and inferior vena cava filter in 15, inferior vena cava filter alone in two, and thrombolysis in two.

Right-ventricular enlargement was found in 78 (50%) patients; 76 were treated with anticoagulation alone or in combination with inferior vena cava filter. For patients with and without right-ventricular enlargement, there was no difference in in-hospital death from PE (0% vs. 1.3%) or all-cause mortality (2.6% vs. 2.5%). The results were unchanged when examined for septal motion abnormality and previous cardiopulmonary disease.

Bottom line: In hemodynamically stable patients with acute pulmonary embolism, right ventricular enlargement does not increase mortality. Further, thrombolytic therapy is unlikely to improve outcomes.

Citation: Stein PD, Beemath A, Matti F, et al. Enlarged right ventricle without shock in acute pulmonary embolus: prognosis. Am J Med. 2008;121:34-42.

What Are Short-term Thromboembolism, Hemorrhage Risks When Interrupting Warfarin Therapy for Procedures?

Background: The risks of thromboembolism and hemorrhage during the periprocedural interruption of warfarin therapy are not known. The risks and benefits of heparin bridging therapy are not well described.

Study design: Multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: Community-based physician practices.

Synopsis: Patients were eligible if they were on long-term warfarin and underwent outpatient procedures requiring interruption of therapy. The primary outcomes were thromboembolism or hemorrhage within 30 days of therapy interruption. In all, 1,024 eligible patients (7.1% considered high risk) had 1,293 interruptions of warfarin therapy. The most common procedures were colonoscopy (25.1%), oral or dental surgery (24.9%), and ophthalmologic surgery (8.9%). Warfarin interruption was five or fewer days in 83.8% of episodes.

Thromboembolism occurred in seven (0.7%) patients, and major or clinically significant bleeding occurred in 23 (0.6%, and 1.7%, respectively) patients. Periprocedural bridging with heparin was used in 88 (8.6%) patients. Of the patients who received periprocedural heparin therapy, none had thromboembolism, and 14 (13%) had bleeding episodes.

Bottom line: In patients whose warfarin therapy is interrupted to undergo outpatient procedures, the risk of thromboembolism is low and the hemorrhagic risk of heparin bridging therapy is significant.

Citation: Garcia DA, Regan S, Henault LE, et al. Risk of thromboembolism with short-term interruption of warfarin therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):63-69.

Are Minor Injuries an Independent Risk Factor For Development of DVT?

Background: Prior studies focus on major injuries as a risk factor for deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) and PE. However, major injury is often associated with other risks for venous thrombosis, such as surgery, plaster casting, hospitalization, and extended bed rest. Risk of DVT with minor injuries that don’t lead to these factors is unknown.

Study design: Large population-based case-control study.

Setting: Six anticoagulation clinics in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: 2,471 consecutive cases (patients with first episode of DVT or PE) and 3,534 controls (partners of cases or random digit dialing contacts) were enrolled. Participants were mailed a questionnaire, including a list of eight common injuries.

Participants with history of cast, surgery, recent hospitalization, extended bed rest, or prior history of cancer were excluded. A subset of patients and controls underwent DNA and blood collection to evaluate for presence of a hypercoagulable state. Of the cases, 289 (11.7%) had a minor injury within three months of the index date, compared with 154 (4.4%) of controls, representing a threefold increased risk of DVT/PE with minor injury (OR 3.1). Partial ruptures of muscles or ligaments in the leg (OR 10.9), multiple simultaneous injuries (OR 9.9), and injury within four weeks of presentation (OR 4.0), were associated with increased risk of DVT/PE.

Patients found to be Factor V Leiden carriers with injury had an almost 50-fold increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared with non-carriers without injury (OR 49.7). Authors appropriately address possible limitations, including recall and referral bias.

Bottom line: Minor leg injury is associated with threefold risk of DVT/PE, especially in the four weeks following injury. Providers should consider short-term prophylactic treatment in patients with Factor V Leiden or high-risk injuries.

Citation: Van Stralen KJ, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. Minor injuries as a risk factor for venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):21-26.

Is Oral Amox-Clav Non-inferior to IV Antibiotics in Pediatric Pyelonephritis?

Background: Present guidelines recommend initial treatment for pediatric pyelonephritis to be a parenteral third-generation cephalosporin followed by oral antibiotics. One prior randomly selected controlled trial compared oral antibiotics only with antibiotics started parenterally, but there was a higher-than-usual incidence of vesicoureteral reflux and female gender in the study.

Study design: Non-inferiority, multicenter, random, open label, controlled trial.

Setting: Twenty-eight pediatric units in northeast Italy from 2000-2005

Synopsis: 502 children age 1 month to less than 7 years with a clinical diagnosis of first occurrence of acute pyelonephritis according to urinalysis and urine culture (requiring two concordant consecutive tests) with at least two of the following conditions: fever of 38 degrees C or more or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or c-reactive protein (CRP), and elevated neutrophil count were randomized to receive oral amoxicillin-clavulanate (AC) or parenteral ceftriaxone followed by oral AC. Exclusion criteria were sepsis, dehydration, vomiting, and creatinine clearance of 70 ml/min or less.

Also, 400 children had dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scintigraphy within 10 days of study entry. Meantime, 223 had repeat DMSA at one year, and 177 had normal scans at study entry so were not repeated. At one year, 20% of patients were lost to follow-up. The primary outcome was renal scarring at one year. Secondary outcomes included time to fever defervescence, reduction in inflammatory indices, and percentage with sterile urine after 72 hours. Intention to treat analysis showed no significant differences between oral (n=244) and parenteral (n=258) treatment, both in the primary outcome 13.7% vs. 17.7% (95% CI, -11.1% to 3.1%), and secondary outcomes.

Bottom line: Treatment with oral antibiotics is as effective as parenteral then oral treatment for first episode of acute pediatric pyelonephritis.

Citation: Montini G, Toffolo A, Zucchetta P, et al. Antibiotic treatment for pyelonephritis in children: multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2007 Aug 25;335(7616):386.

Statins/Beta‐Blockers and Mortality after Vascular Surgery

Vascular surgery has higher morbidity and mortality than other noncardiac surgeries. Despite the identification of vascular surgery as higher risk, 30‐day mortality for this surgery has remained at 3%10%. Few studies have examined longer‐term outcomes, but higher mortality rates have been reported, for example, 10%30% 6 months after surgery, 20%40% 1 year after surgery, and 30%50% 5 years after surgery.15 Postoperative adverse events have been found to be highly correlated with perioperative ischemia and infarction.68 Perioperative beta‐blockers have been widely studied and have been shown to benefit patients undergoing noncardiac surgery generally and vascular surgery specifically.9, 10 However, 2 recent trials of perioperative beta‐blockers in noncardiac and vascular surgery patients failed to show an association with 18‐month and 30‐day postoperative morbidity and mortality, respectively.11, 12 In addition, the authors of a recent meta‐analysis of perioperative beta‐blockers suggested more studies were needed.13 Furthermore, there have been promising new data on the use of perioperative statins.1418 Finally, as a recent clinical trial of revascularization before vascular surgery did not demonstrate an advantage over medical management, the identification of which perioperative medicines improve postoperative outcomes and in what combinations becomes even more important.19 We sought to ascertain if the ambulatory use of statins and/or beta‐blockers within 30 days of surgery was associated with a reduction in long‐term mortality.

METHODS

Setting and Subjects

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a regional Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) administrative and relational database, the Consumer Health Information and Performance Sets (CHIPs), which automatically extracts data from electronic medical records of all facilities in the Veterans Integrated Services Network 20, which encompasses Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. CHIPs contains information on both outpatient and inpatient environments, and a record is generated for every contact a patient makes with the VA health care system, which includes picking up prescription medications, laboratory values, demographic information, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD‐9), codes, and vital status. In addition, we used the Beneficiary Identification and Records Locator Subsystem database, which is the national VA death index and includes Social Security Administration data that has been shown to be 90%95% complete for assessing vital status.20

Data for all patients who had vascular surgery at 5 VA medical centers in the region from January 1998 to March 2005 was ascertained. If a patient had a second operation within 2 years of the first, the patient was censored at the date of the second operation. A patient was defined as taking a statin or beta‐blocker if a prescription for either of these medications had been picked up within 30 days before or after surgery. The IRB at the Portland VA Medical Center approved the study with a waiver of informed consent.

Data Elements

For every patient we noted the type of vascular surgery (carotid, aortic, lower extremity bypass, or lower extremity amputation), age, sex, comorbid conditions (hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], chronic kidney disease [CKD], coronary artery disease [CAD], heart failure), tobacco use, ethnicity, nutritional status (serum albumin), and medication use, defined as filling a prescription within 30 days before surgery (insulin, aspirin, angiotensin‐converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor, and clonidine). Each patient was assigned a revised cardiac risk index (RCRI) score.21 For each the risk factors: use of insulin, CAD, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, CKD, and high‐risk surgery (intrathoracic, intraperitoneal, or suprainguinal vascular procedures) 1 point was assigned. These variables were defined according to ICD‐9 codes. CKD was defined as either an ICD‐9 code for CKD or a serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL. Patients were identified by the index vascular surgery using ICD‐9 codes in the CHIPs database, and both inpatient and outpatient data were extracted.

Statistical Analysis

All patients were censored at the point of last contact up to 5 years after surgery to focus on more clinically relevant long‐term outcomes possibly associated with vascular surgery. We conducted 3 separate analyses: (1) statin exposure regardless of beta‐blocker exposure; (2) beta‐blocker exposure regardless of statin exposure, and; (3) combined exposure to statins and beta‐blockers.

Propensity score methods were used to adjust for imbalance in the baseline characteristics between statin users and nonusers, beta‐blocker users and nonusers, and combination statin and beta‐blocker users and nonusers.22, 23 The range of the propensity score distribution was similar in drug users and nonusers in the individual analyses. There was sufficient overlap between the 2 groups in each stratum. To derive propensity scores for the individual drug analyses, statin use and beta‐blocker use were modeled independently with the demographic and clinical variables using stepwise logistic regression with a relaxed entry criterion of = 0.20. Only 1 variable (hyperlipidemia) remained significantly different between statin users and nonusers, and it was included in the subsequent analyses as a potential confounder. The variable albumin had 511 missing values. To keep this variable in the propensity scores, the missing values were replaced by the predicted values of albumin from the multiple linear regression model that included the other demographic variables. The propensity scores were grouped into quintiles and used as a stratification variable in the subsequent analyses. To confirm that the propensity score method reduced the imbalances, the demographic and clinical characteristics of statin and beta‐blocker users and nonusers and combination users and nonusers were compared using Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenzel tests with the respective propensity score as a stratification variable.

For the combined use of both study drugs, we performed univariate analysis with adjustment only for RCRI (as this was a powerful predictor of mortality in our dataset; Table 1) as well as a propensity score analysis in an exploratory manner. There have been limited applications of propensity score methods to multiple treatment groups. Similar to that in the study by Huang et al.,24 we developed a multinomial baseline response logit model to obtain 3 separate propensity scores (statin only vs. none, beta‐blocker only vs. none, and both vs. none). Because of the limited sample size, the data were stratified according to the median split of each propensity score. Each score had similar ranges for each treatment group. All but 5 variables (CAD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ACE inhibitor use, and type of surgery) were balanced after accounting for strata. These 5 variables were then included in the final stratified Cox regression model as potential confounders.

| Variable | Level | N (%) Overall N = 3062 | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Chi‐square P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 67 (5974) | 1.04 (1.04, 1.05)a | <.0001 | |

| Sex | Female | 45 (1) | 0.89 (0.53, 1.51) | .6704 |

| Male | 3017 (99) | 1 | 1.0000 | |

| Preoperative medical conditions | HTN | 2415 (79) | 1.32 (1.13, 1.55) | .0006 |

| CVA/TIA | 589 (19) | 1.05 (0.90, 1.22) | .5753 | |

| CA | 679 (22) | 1.55 (1.36, 1.78) | <.0001 | |

| DM | 1474 (48) | 1.75 (1.54, 1.98) | <.0001 | |

| Lipid | 872 (28) | 0.84 (0.74, 0.97) | .0187 | |

| COPD | 913 (30) | 1.68 (1.48, 1.90) | <.0001 | |

| CAD | 1491 (49) | 1.46 (1.29, 1.66) | <.0001 | |

| CHF | 747 (24) | 2.44 (2.15, 2.77) | <.0001 | |

| CKD | 443 (14) | 2.32 (2.00, 2.69) | <.0001 | |

| Blood chemistry | Creatinine > 2 | 229 (7) | 2.73 (2.28, 3.28) | <.0001 |

| Albumin 3.5 | 596 (23) | 2.70 (2.35, 3.10) | <.0001 | |

| Medication use | Aspirin | 1789 (58) | 1.10 (0.97, 1.25) | .1389 |

| ACE inhibitor | 1250 (41) | 0.93 (0.82, 1.06) | .2894 | |

| Insulin | 478 (16) | 1.31 (1.12, 1.54) | .0007 | |

| Clonidine | 115 (4) | 1.68 (1.29, 2.20) | .0001 | |

| Perioperative medication | Statinb | 1346 (44) | 0.66 (0.58, 0.75) | <.0001 |

| Beta‐blockerc | 1617 (53) | 0.74 (0.66, 0.84) | <.0001 | |

| Statin only | 414 (14) | 0.69 (0.56, 0.84) | .0002 | |

| Beta‐blocker only | 685 (22) | 0.81 (0.69, 0.95) | .0079 | |

| Statin and beta‐blocker | 932 (30) | 0.57 (0.49, 0.67) | <.0001 | |

| Noned | 1031 (34) | 1 | 1.0000 | |

| Type of surgery | Aorta | 232 (8) | 1.34 (1.01, 1.77) | <.0001 |

| Carotid | 875 (29) | 1 | ||

| Amputation | 867 (28) | 2.80 (2.36, 3.32) | ||

| Bypass | 1088 (36) | 1.57 (1.32, 1.87) | ||

| RCRI | 0 | 1223 (40) | 1 | <.0001 |

| 1 | 1005 (33) | 1.33 (1.13, 1.55) | ||

| 2 | 598 (20) | 2.22 (1.88, 2.62) | ||

| 3 | 200 (7) | 3.16 (2.54, 3.93) | ||

| 4 | 36 (1) | 4.82 (3.15, 7.37) | ||

| Year surgery occurred | 1998 | 544 (18) | 1 | .6509 |

| 1999 | 463 (15) | 0.91 (0.75, 1.10) | ||

| 2000 | 420 (14) | 0.93 (0.77, 1.13) | ||

| 2001 | 407 (13) | 0.93 (0.75, 1.14) | ||

| 2002 | 374 (12) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.40) | ||

| 2003 | 371 (12) | 1.15 (0.90, 1.47) | ||

| 2004 | 407 (13) | 0.97 (0.72, 1.31) | ||

| 2005 | 76 (3) | 0.68 (0.28, 1.65) | ||

| Tobacco user | Yes | 971 (32) | 0.90 (0.76, 1.08) | .4762 |

| No | 649 (21) | 1 | ||

| Null | 1442 (47) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.13) | ||

| Ethnicity | White | 563 (18) | 1 | .0366 |

| Other | 39 (1) | 0.98 (0.55, 1.76) | ||

| Unknown | 2460 (80) | 1.24 (1.05, 1.46) | ||

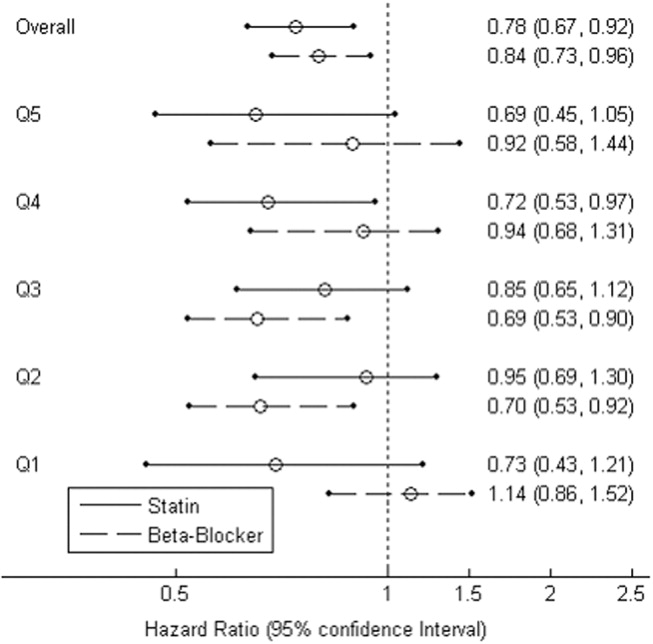

To comment on patient‐specific risk by stratification with the RCRI, we used a fixed time point of the 2‐year mortality estimated from the Cox regression model to analyze use of study drugs singly or in combination compared with use of neither.

Chi‐square tests were used to categorize and compare demographic and clinical characteristics of statin users and nonusers, of beta‐blocker users and nonusers, and combination users and nonusers. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan‐Meier method and compared using the log‐rank test. Stratified or unstratified Cox regression was used to estimate the hazard ratios of statins and beta‐blockers, with or without adjustment for the propensity score. All analyses were performed using SAS (Statistical Analysis System) software, version 9.1.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The study included 3062 patients whose median age was 67 (interquartile range, 5974; Table 1). Ninety‐nine percent of the study patients were men. Overall, ambulatory use of statins and beta‐blockers was found in 44% and 53% of patients, respectively, and combination use occurred in 30%. Sixty‐one percent of patients had an RCRI of 1 or greater; among them 71% were statin users (Table 2), 68% were beta‐blocker users (Table 3), and 75% were combination users (Table 4). Sixty‐four percent of surgeries were either lower extremity bypass or amputation, 29% were carotid, and 8% aortic. Median follow‐up for all patients was 2.7 years (interquartile range, 1.24.6). Of the whole study cohort, 53% and 62% filled a prescription for a statin or beta‐blocker within 1 year of surgery, respectively, and 58% and 67% filled a prescription within 2 years of surgery, respectively. Overall mortality at 30 days was 3%, at 1 year 14%, and at 2 years 22%.

| Variable, N (%) | Level | Overall (N = 3062) | Statin users (N = 1346 [44]) | Statin nonusers (N = 1716 [56]) | Unadjusted P value | Propensity‐adjusted P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 67 (5974) | 66 (5973) | 68 (6075) | <.0001 | .9934 | |

| Sex | Female | 45 (1) | 15 (1) | 30 (2) | .1480 | .7822 |

| Male | 3017 (99) | 1331 (99) | 1686 (98) | |||

| Preoperative medical conditions | HTN | 2415 (79) | 1176 (87) | 1239 (72) | <.0001 | .2984 |

| CVA/TIA | 589 (19) | 328 (24) | 261 (15) | <.0001 | .3935 | |

| CA | 679 (22) | 307 (23) | 372 (22) | .4550 | .8404 | |

| DM | 1474 (48) | 666 (49) | 808 (47) | .1883 | .5504 | |

| Lipid | 872 (28) | 629 (47) | 243 (14) | <.0001 | .0246 | |

| COPD | 913 (30) | 411 (31) | 502 (29) | .4419 | .8435 | |

| CAD | 1491 (49) | 837 (62) | 654 (38) | <.0001 | .4720 | |

| CHF | 747 (24) | 370 (27) | 377 (22) | .0004 | .4839 | |

| CKD | 443 (14) | 208 (15) | 235 (14) | .1698 | .9990 | |

| Blood chemistry | Creatinine > 2 | 229 (7) | 101 (8) | 128 (7) | .9629 | .6911 |

| Albumin 3.5 | 596 (23) | 191 (16) | 405 (30) | <.0001 | .5917 | |

| Medication use | Aspirin | 1789 (58) | 904 (67) | 885 (52) | <.0001 | .6409 |

| Ace inhibitor | 1250 (41) | 712 (53) | 538 (31) | <.0001 | .6075 | |

| Beta‐blocker | 1220 (40) | 767 (57) | 453 (26) | <.0001 | .4058 | |

| Insulin | 478 (16) | 254 (19) | 224 (13) | <.0001 | .7919 | |

| Clonidine | 115 (4) | 61 (5) | 54 (3) | .0454 | .6141 | |

| Type of surgery | Aorta | 232 (8) | 106 (8) | 126 (7) | <.0001 | .9899 |

| Carotid | 875 (29) | 510 (38) | 365 (21) | |||

| Amputation | 867 (28) | 274 (20) | 593 (35) | |||

| Bypass | 1088 (36) | 456 (34) | 632 (37) | |||

| RCRI | 0 | 1223 (40) | 389 (29) | 834 (49) | <.0001 | .9831 |

| 1 | 1005 (33) | 507 (38) | 498 (29) | |||

| 2 | 598 (20) | 318 (24) | 280 (16) | |||

| 3 | 200 (7) | 109 (8) | 91 (5) | |||

| 4 | 36 (1) | 23 (1) | 13 (0.76) | |||

| Year of surgery | 1998 | 544 (18) | 134 (10) | 410 (24) | <.0001 | 1 |

| 1999 | 463 (15) | 163 (12) | 300 (17) | |||

| 2000 | 420 (13) | 178 (13) | 242 (14) | |||

| 2001 | 407 (13) | 188 (14) | 219 (13) | |||

| 2002 | 374 (12) | 194 (14) | 180 (10) | |||

| 2003 | 371 (12) | 209 (16) | 162 (9) | |||

| 2004 | 407 (13) | 229 (17) | 178 (10) | |||

| 2005 | 76 (3) | 51 (4) | 25 (1.5) | |||

| Tobacco user | Yes | 971 (32) | 494 (37) | 477 (28) | <.0001 | .9809 |

| No | 649 (21) | 335 (25) | 314 (18) | |||

| Null | 1442 (47) | 517 (38) | 925 (54) | |||

| Ethnicity | White | 563 (18) | 263 (20) | 300 (17) | .1544 | .9475 |

| Other | 39 (1) | 13 (1) | 26 (1.5) | |||

| Unknown | 2460 (80) | 1070 (79) | 1390 (81) | |||

| Variable, N (%) | Level | Overall N = 3062 | BB users N = 1617 (53) | Non‐BB users N = 1445 (47) | Unadjusted P value | Propensity‐adjusted P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 67 (5974) | 67 (5975) | 68 (6076) | .0526 | .7671 | |

| Sex | Female | 45 (1) | 12 (1) | 33 (2) | .0004 | .585 |

| Male | 3017 (99) | 1605 (99) | 1412 (98) | |||

| Preoperative medical conditions | HTN | 2415 (79) | 1398 (86) | 1017 (70) | <.0001 | .1837 |

| CVA/TIA | 589 (19) | 364 (23) | 225 (16) | <.0001 | .3206 | |

| CA | 679 (22) | 359 (22) | 320 (22) | .9701 | .4288 | |

| DM | 1474 (48) | 739 (46) | 735 (51) | .0043 | .6329 | |

| Lipid | 872 (28) | 555 (34) | 317 (22) | <.0001 | .7180 | |

| COPD | 913 (30) | 487 (30) | 426 (29) | .7007 | .8022 | |

| CAD | 1491 (49) | 975 (60) | 516 (36) | <.0001 | .3496 | |

| CHF | 747 (24) | 439 (27) | 308 (21) | .0002 | .6509 | |

| CKD | 443 (14) | 248 (15) | 195 (13) | .1480 | .8544 | |

| Blood chemistry | Creatinine > 2 | 229 (7) | 132 (8) | 97 (7) | .1277 | .5867 |

| Albumin 3.5 | 596 (23) | 252 (18) | 344 (30) | <.0001 | .5347 | |

| Medication use | Aspirin | 1789 (58) | 1046 (65) | 743 (51) | <.0001 | .4942 |

| Ace inhibitor | 1250 (41) | 760 (47) | 490 (34) | <.0001 | .4727 | |

| Statin | 1220 (40) | 932 (58) | 414 (29) | <.0001 | .3706 | |

| Insulin | 478 (16) | 255 (16) | 223 (15) | .7973 | .5991 | |

| Clonidine | 115 (4) | 77 (5) | 38 (3) | .0019 | .8241 | |

| Type of surgery | Aorta | 232 (8) | 176 (11) | 56 (4) | <.0001 | .5664 |

| Carotid | 875 (29) | 515 (32) | 360 (25) | |||

| Amputation | 867 (28) | 339 (21) | 528 (37) | |||

| Bypass | 1088 (36) | 587 (36) | 501 (35) | |||

| RCRI | 0 | 1223 (40) | 518 (32) | 705 (49) | <.0001 | .5489 |

| 1 | 1005 (33) | 583 (36) | 422 (29) | |||

| 2 | 598 (20) | 358 (22) | 240 (17) | |||

| 3 | 200 (7) | 130 (8) | 70 (5) | |||

| 4 | 36 (1) | 28 (2) | 8 (1) | |||

| Year of surgery | 1998 | 544 (18) | 200 (12) | 344 (24) | <.0001 | .3832 |

| 1999 | 463 (15) | 211 (13) | 252 (17) | |||

| 2000 | 420 (13) | 210 (13) | 210 (15) | |||

| 2001 | 407 (13) | 209 (13) | 198 (14) | |||

| 2002 | 374 (12) | 220 (14) | 154 (11) | |||

| 2003 | 371 (12) | 238 (15) | 133 (9) | |||

| 2004 | 407 (13) | 279 (17) | 128 (9) | |||

| 2005 | 76 (3) | 50 (3) | 26 (2) | |||

| Tobacco user | Yes | 971 (32) | 569 (35) | 402 (28) | <.0001 | .9025 |

| No | 649 (21) | 370 (23) | 279 (19) | |||

| Null | 1442 (47) | 678 (42) | 764 (53) | |||

| Ethnicity | White | 563 (18) | 309 (19) | 254 (18) | .4962 | .8762 |

| Other | 39 (1) | 19 (1) | 20 (1) | |||

| Unknown | 2460 (80) | 1289 (80) | 1171 (81) | |||

| N (%) Variable | Level | Overall N = 3062 | BB alone N = 685 (22) | Statin alone N = 414 (14) | Both drugs N = 932 (30) | Neither drug N = 1031 (34) | Unadjusted P value | Propensity‐adjusted P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 67 (5974) | 68 (6075) | 67 (6075) | 66 (5973) | 69 (6076) | .0029 | .9824 | |

| Sex | Female | 45 (1) | 7 (1) | 10 (2) | 5 (1) | 23 (2) | .0042 | .5815 |

| Male | 3017 (99) | 678 (99) | 404 (98) | 927 (99) | 1008 (98) | |||

| Preoperative medical conditions | HTN | 2415 (79) | 560 (82) | 338 (82) | 838 (90) | 679 (66) | <.0001 | .0251 |

| CVA/TIA | 589 (19) | 127 (19) | 91 (22) | 237 (25) | 134 (13) | <.0001 | .4543 | |

| CA | 679 (22) | 150 (22) | 98 (24) | 209 (22) | 222 (22) | .8379 | .9749 | |

| DM | 1474 (48) | 291 (43) | 218 (53) | 448 (48) | 517 (50) | .0031 | .3943 | |

| Lipid | 872 (28) | 125 (18) | 199 (48) | 430 (46) | 118 (11) | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| COPD | 913 (30) | 199 (29) | 123 (30) | 288 (9) | 303 (29) | .8475. | .9769 | |

| CAD | 1491 (49) | 327 (48) | 189 (46) | 648 (70) | 327 (32) | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| CHF | 747 (24) | 163 (24) | 94 (23) | 276 (30) | 214 (21) | <.0001 | .7031 | |

| CKD | 443 (14) | 92 (13) | 52 (13) | 156 (17) | 143 (14) | .1120 | .8364 | |

| Blood chemistry | Creatinine > 2 | 229 (7) | 52 (8) | 21 (5) | 80 (9) | 76 (7) | .1619 | .7184 |

| Albumin 3.5 | 596 (23) | 134 (20) | 73 (20) | 118 (14) | 271 (34) | <.0001 | .2846 | |

| Medication use | Aspirin | 1789 (58) | 398 (58) | 256 (62) | 648 (70) | 487 (47) | <.0001 | .2334 |

| Ace inhibitor | 1250 (41) | 264 (39) | 216 (52) | 496 (53) | 274 (27) | <.0001 | .0216 | |

| Insulin | 478 (16) | 93 (14) | 92 (22) | 162 (17) | 131 (13) | <.0001 | .2952 | |

| Clonidine | 115 (4) | 28 (4) | 12 (3) | 49 (5) | 26 (3) | .0107 | .8035 | |

| Type of surgery | Aorta | 232 (8) | 78 (11) | 8 (2) | 98 (11) | 48 (5) | <.0001 | .008 |

| Carotid | 875 (29) | 165 (24) | 160 (39) | 350 (38) | 200 (19) | |||

| Amputation | 867 (28) | 164 (24) | 99 (24) | 175 (19) | 429 (42) | |||

| Bypass | 1088 (36) | 278 (41) | 147 (36) | 309 (33) | 354 (34) | |||

| RCRI | 0 | 1223 (40) | 288 (42) | 159 (38) | 230 (25) | 546 (53) | <.0001 | .5392 |

| 1 | 1005 (33) | 219 (32) | 143 (35) | 364 (39) | 279 (27) | |||

| 2 | 598 (20) | 125 (18) | 85 (21) | 233 (25) | 155 (15) | |||

| 3 | 200 (7) | 46 (7) | 25 (6) | 84 (9) | 45 (4) | |||

| 4 | 36 (1) | 7 (1) | 2 (0) | 21 (2) | 6 (1) | |||

| Year of surgery | 1998 | 544 (18) | 126 (18) | 60 (14) | 74 (8) | 284 (28) | <.0001 | .3105 |

| 1999 | 463 (15) | 111 (16) | 63 (15) | 100 (11) | 189 (18) | |||

| 2000 | 420 (13) | 87 (13) | 55 (13) | 123 (13) | 155 (15) | |||

| 2001 | 407 (13) | 84 (12) | 63 (15) | 125 (13) | 135 (13) | |||

| 2002 | 374 (12) | 81 (12) | 55 (13) | 139 (15) | 99 (10 | |||

| 2003 | 371 (12) | 85 (13) | 56 (14) | 153 (16) | 77 (7) | |||

| 2004 | 407 (13) | 96 (14) | 46 (11) | 183 (20) | 82 (8) | |||

| 2005 | 76 (3) | 15 (2) | 16 (4) | 35 (4) | 10 (1) | |||

| Tobacco user | Yes | 971 (32) | 227 (33) | 152 (37) | 342 (37) | 250 (24) | <.0001 | .3914 |

| No | 649 (21) | 134 (20) | 99 (24) | 236 (25) | 180 (17) | |||

| Null | 1442 (47) | 324 (47) | 163 (39) | 354 (38) | 601 (58) | |||

| Ethnicity | White | 563 (18) | 115 (17) | 69 (17) | 194 (21) | 185 (18) | .2821 | .9771 |

| Other | 39 (1) | 10 (1) | 4 (1) | 9 (1) | 16 (2) | |||

| Unknown | 2460 (80) | 560 (82) | 341 (82) | 729 (78) | 830 (81) | |||

Univariate Survival Analysis

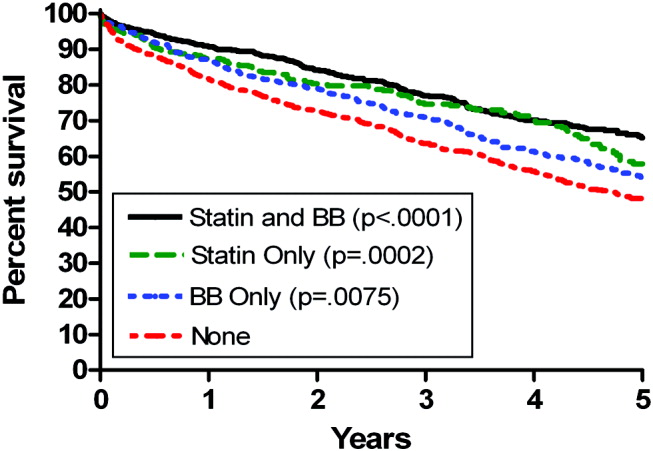

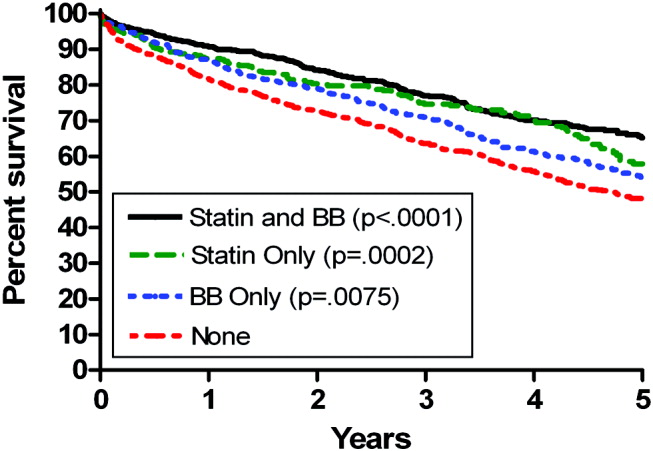

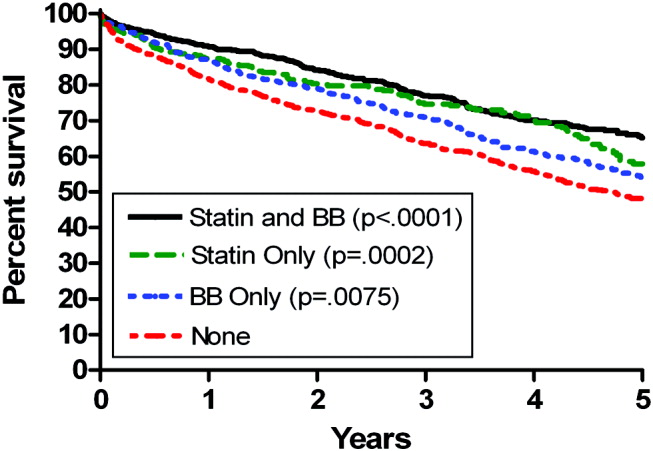

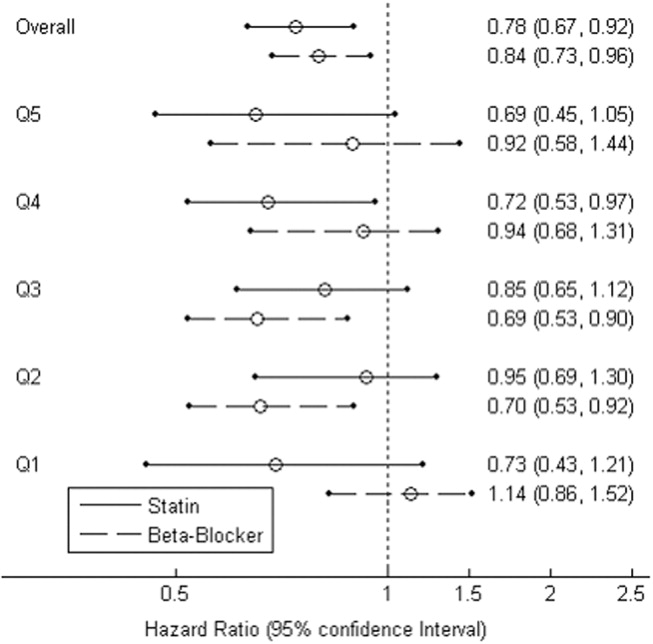

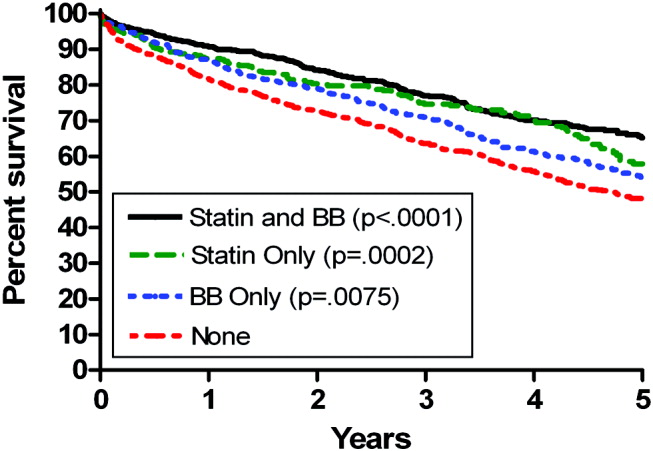

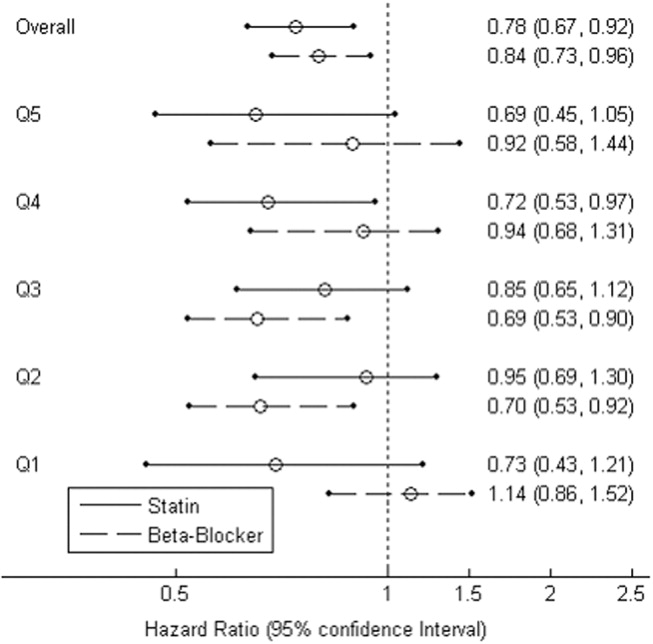

Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed a strong effect of the composite RCRI, which was predictive of mortality in a linear fashion over the course of the study compared with an RCRI of 0 (Table 1). Univariate analysis showed significant associations with decreased mortality for statins (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.66 [95% CI 0.580.75], P < .0001) and beta‐blockers (HR = 0.74 [95% CI 0.660.84], P = .0001); see Table 1. Of note, compared with that in 1998, mortality did not change for all the years for which data were complete. In addition, compared with taking neither study drug, taking a statin only, a beta‐blocker only, or both was associated with decreased mortality (P = .0002, P = .0079, and P < .0001, respectively; Fig. 1).

Propensity Score Analysis for Single Study Drug