User login

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida who has written about medical topics from nasty infections to ethical dilemmas, runaway tumors to tornado-chasing doctors. He travels the globe gathering conference health news and lives in West Palm Beach.

Blood markers can detect early pancreatic cancer

A blood test has been found to be effective for detecting early pancreatic cancer in those at high risk, with the potential to find the deadly cancer at a time when it is more likely to be treatable with surgery, according to phase 2b findings recently published in Science Translational Medicine.

In a 337-person study, researchers found that a blood panel for the protein thrombospondin-2 (THBS2) and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), measured with a standard ELISA test, together detected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with a specificity of 98% and a sensitivity of 87%. The test was effective at distinguishing patients with PDAC from controls and those with benign pancreatic disease across all stages of the cancer, wrote Kenneth Zaret, PhD, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

CA19-9 is already a known marker for PDAC, but it is a deeply flawed one because it is also elevated in people with nonmalignant pancreatic conditions and can produce false negatives in people without certain antibodies.

But, together, researchers found, THBS2 and CA19-9 make a good pairing for early detection. In the paper, researchers described cases of patients who had no CA19-9 signal at all, likely because they were Lewis-antigen negative, but who had high THBS2 levels. There were also several cases in which THBS2 levels overlapped with the upper end of the normal range but with elevated CA19-9 levels.

“Thus, the two markers appeared to be complementary in their ability to detect PDAC,” Dr. Zaret wrote.

Researchers were able to test for markers by reprogramming advanced PDAC cells to induce a pluripotent stem cell–like state.

Because of the low prevalence of PDAC in the general population, researchers are not recommending the panel as a general screening test.

“We suggest that the THBS2/CA19-9 marker panel could serve as a low-cost, nonintervention screening tool in asymptomatic individuals who have a high risk of developing PDAC,” Dr. Zaret wrote, “and also in patients who are newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus that developed as a result of pancreatic injury – but not in the general population.”

A blood test has been found to be effective for detecting early pancreatic cancer in those at high risk, with the potential to find the deadly cancer at a time when it is more likely to be treatable with surgery, according to phase 2b findings recently published in Science Translational Medicine.

In a 337-person study, researchers found that a blood panel for the protein thrombospondin-2 (THBS2) and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), measured with a standard ELISA test, together detected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with a specificity of 98% and a sensitivity of 87%. The test was effective at distinguishing patients with PDAC from controls and those with benign pancreatic disease across all stages of the cancer, wrote Kenneth Zaret, PhD, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

CA19-9 is already a known marker for PDAC, but it is a deeply flawed one because it is also elevated in people with nonmalignant pancreatic conditions and can produce false negatives in people without certain antibodies.

But, together, researchers found, THBS2 and CA19-9 make a good pairing for early detection. In the paper, researchers described cases of patients who had no CA19-9 signal at all, likely because they were Lewis-antigen negative, but who had high THBS2 levels. There were also several cases in which THBS2 levels overlapped with the upper end of the normal range but with elevated CA19-9 levels.

“Thus, the two markers appeared to be complementary in their ability to detect PDAC,” Dr. Zaret wrote.

Researchers were able to test for markers by reprogramming advanced PDAC cells to induce a pluripotent stem cell–like state.

Because of the low prevalence of PDAC in the general population, researchers are not recommending the panel as a general screening test.

“We suggest that the THBS2/CA19-9 marker panel could serve as a low-cost, nonintervention screening tool in asymptomatic individuals who have a high risk of developing PDAC,” Dr. Zaret wrote, “and also in patients who are newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus that developed as a result of pancreatic injury – but not in the general population.”

A blood test has been found to be effective for detecting early pancreatic cancer in those at high risk, with the potential to find the deadly cancer at a time when it is more likely to be treatable with surgery, according to phase 2b findings recently published in Science Translational Medicine.

In a 337-person study, researchers found that a blood panel for the protein thrombospondin-2 (THBS2) and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), measured with a standard ELISA test, together detected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with a specificity of 98% and a sensitivity of 87%. The test was effective at distinguishing patients with PDAC from controls and those with benign pancreatic disease across all stages of the cancer, wrote Kenneth Zaret, PhD, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

CA19-9 is already a known marker for PDAC, but it is a deeply flawed one because it is also elevated in people with nonmalignant pancreatic conditions and can produce false negatives in people without certain antibodies.

But, together, researchers found, THBS2 and CA19-9 make a good pairing for early detection. In the paper, researchers described cases of patients who had no CA19-9 signal at all, likely because they were Lewis-antigen negative, but who had high THBS2 levels. There were also several cases in which THBS2 levels overlapped with the upper end of the normal range but with elevated CA19-9 levels.

“Thus, the two markers appeared to be complementary in their ability to detect PDAC,” Dr. Zaret wrote.

Researchers were able to test for markers by reprogramming advanced PDAC cells to induce a pluripotent stem cell–like state.

Because of the low prevalence of PDAC in the general population, researchers are not recommending the panel as a general screening test.

“We suggest that the THBS2/CA19-9 marker panel could serve as a low-cost, nonintervention screening tool in asymptomatic individuals who have a high risk of developing PDAC,” Dr. Zaret wrote, “and also in patients who are newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus that developed as a result of pancreatic injury – but not in the general population.”

Key clinical point: A blood panel was able to detect pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in high-risk people across all stages of their cancer.

Major finding: Using a panel of the protein thrombospondin-2 and cancer antigen 19-9, the specificity was 98% and the sensitivity was 87%.

Data source: A phase 2b study of 337 people, including those at high-risk for PDAC, those with benign pancreatic disease, and control subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Zaret reported consulting work with BetaLogics/J&J and RaNA Therapeutics.

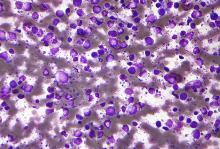

Midostaurin improves survival in new AML

Adding the multitargeted kinase inhibitor midostaurin to standard chemotherapy led to significantly longer overall and event-free survival, compared with placebo and standard chemotherapy in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients with FLT3 gene mutations, according to phase III trial results published in the New England Journal of Medicine.*

About 30% of AML patients have mutations to the FLT3 gene – with three-quarters of those internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations, which involves duplication of between 3 and 100 amino acids in the juxtamembrane region. These mutations are linked with a high relapse rate and poor prognosis, especially when there is a high ratio of these mutations to wild-type FLT3. About 8% of patients with newly diagnosed AML have an FLT3 point mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD), but the effect of these on prognosis isn’t clear.

In the trial, called RATIFY and conducted at 225 sites in 17 countries, 360 patients were randomized to the midostaurin group and 357* to placebo, and they were treated from 2008 to 2013. In all, 29.8% of patients were “ITD high,” meaning their ITD FLT3 mutation to wild-type FLT3 ratio was higher than 0.7, and 47.6% were “ITD low,” with a mutation-to-wild-type FLT3 ratio of 0.5 to 0.7. A total of 22.6% of patients had TKD mutations.

Patients received standard induction chemotherapy, with daunorubicine and cytarabine, and on days 8 through 21 either 50 mg of midostaurin or placebo orally twice a day. Patients were given an identical second cycle of induction therapy, with midostaurin or placebo, if they showed definitive clinically significant residual leukemia after the first induction treatment.

Those who achieved complete remission after induction were given 4, 28-day cycles of consolidation treatment, with midostaurin or placebo on days 8 through 21. If they stayed in remission after that, they were given maintenance of 12, 28-day cycles of midostaurin or placebo.

They were not required to receive hematopoetic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), but it was performed at investigator discretion.

Midostaurin improved survival but not rates of complete remission as defined in the trial protocol, researchers reported.

The hazard ratio for death in the midostaurin group was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.96; one-sided P = .0009). The 4-year overall survival rate was 51.4% for the midostaurin group and 44.3% for the placebo group. Midostaurin was shown to benefit all mutation subgroups, but with no greater benefit in one group than another.

Patients in the midostaurin group had a 21.6% lower likelihood of having an event, defined as failure to achieve protocol-defined complete remission, relapse or death without relapse.

There was no significant difference between the groups in complete remission, which under protocol had to occur by day 60.

HSCT was performed in 57% of patients – during the first complete remission in 28.1% of the midostaurin group and in 22.7% during the first complete remission in the placebo group. For those who were transplanted after the first complete remission, no treatment effect was seen.

Researchers noted that there was a therapeutic benefit even among patients with ITD mutations but with a low allelic burden, in whom the disease might be due largely to mutations other than FLT3.

“It is possible that the benefit of midostaurin, which is a multitargeted kinase inhibitor, might lie beyond its ability to inhibit FLT3,” possibly through inhibition of KIT, researchers said.

They also noted that as the trial went on, more and more investigators decided to treat patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, based on newly reported data elsewhere. Since midostaurin was discontinued at the time of transplant, that could have limited exposure to the drug and limited its effect.

*CORRECTION 7/5/2017: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of patients in the placebo group as well as where the study originally appeared.

Adding the multitargeted kinase inhibitor midostaurin to standard chemotherapy led to significantly longer overall and event-free survival, compared with placebo and standard chemotherapy in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients with FLT3 gene mutations, according to phase III trial results published in the New England Journal of Medicine.*

About 30% of AML patients have mutations to the FLT3 gene – with three-quarters of those internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations, which involves duplication of between 3 and 100 amino acids in the juxtamembrane region. These mutations are linked with a high relapse rate and poor prognosis, especially when there is a high ratio of these mutations to wild-type FLT3. About 8% of patients with newly diagnosed AML have an FLT3 point mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD), but the effect of these on prognosis isn’t clear.

In the trial, called RATIFY and conducted at 225 sites in 17 countries, 360 patients were randomized to the midostaurin group and 357* to placebo, and they were treated from 2008 to 2013. In all, 29.8% of patients were “ITD high,” meaning their ITD FLT3 mutation to wild-type FLT3 ratio was higher than 0.7, and 47.6% were “ITD low,” with a mutation-to-wild-type FLT3 ratio of 0.5 to 0.7. A total of 22.6% of patients had TKD mutations.

Patients received standard induction chemotherapy, with daunorubicine and cytarabine, and on days 8 through 21 either 50 mg of midostaurin or placebo orally twice a day. Patients were given an identical second cycle of induction therapy, with midostaurin or placebo, if they showed definitive clinically significant residual leukemia after the first induction treatment.

Those who achieved complete remission after induction were given 4, 28-day cycles of consolidation treatment, with midostaurin or placebo on days 8 through 21. If they stayed in remission after that, they were given maintenance of 12, 28-day cycles of midostaurin or placebo.

They were not required to receive hematopoetic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), but it was performed at investigator discretion.

Midostaurin improved survival but not rates of complete remission as defined in the trial protocol, researchers reported.

The hazard ratio for death in the midostaurin group was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.96; one-sided P = .0009). The 4-year overall survival rate was 51.4% for the midostaurin group and 44.3% for the placebo group. Midostaurin was shown to benefit all mutation subgroups, but with no greater benefit in one group than another.

Patients in the midostaurin group had a 21.6% lower likelihood of having an event, defined as failure to achieve protocol-defined complete remission, relapse or death without relapse.

There was no significant difference between the groups in complete remission, which under protocol had to occur by day 60.

HSCT was performed in 57% of patients – during the first complete remission in 28.1% of the midostaurin group and in 22.7% during the first complete remission in the placebo group. For those who were transplanted after the first complete remission, no treatment effect was seen.

Researchers noted that there was a therapeutic benefit even among patients with ITD mutations but with a low allelic burden, in whom the disease might be due largely to mutations other than FLT3.

“It is possible that the benefit of midostaurin, which is a multitargeted kinase inhibitor, might lie beyond its ability to inhibit FLT3,” possibly through inhibition of KIT, researchers said.

They also noted that as the trial went on, more and more investigators decided to treat patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, based on newly reported data elsewhere. Since midostaurin was discontinued at the time of transplant, that could have limited exposure to the drug and limited its effect.

*CORRECTION 7/5/2017: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of patients in the placebo group as well as where the study originally appeared.

Adding the multitargeted kinase inhibitor midostaurin to standard chemotherapy led to significantly longer overall and event-free survival, compared with placebo and standard chemotherapy in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients with FLT3 gene mutations, according to phase III trial results published in the New England Journal of Medicine.*

About 30% of AML patients have mutations to the FLT3 gene – with three-quarters of those internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations, which involves duplication of between 3 and 100 amino acids in the juxtamembrane region. These mutations are linked with a high relapse rate and poor prognosis, especially when there is a high ratio of these mutations to wild-type FLT3. About 8% of patients with newly diagnosed AML have an FLT3 point mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD), but the effect of these on prognosis isn’t clear.

In the trial, called RATIFY and conducted at 225 sites in 17 countries, 360 patients were randomized to the midostaurin group and 357* to placebo, and they were treated from 2008 to 2013. In all, 29.8% of patients were “ITD high,” meaning their ITD FLT3 mutation to wild-type FLT3 ratio was higher than 0.7, and 47.6% were “ITD low,” with a mutation-to-wild-type FLT3 ratio of 0.5 to 0.7. A total of 22.6% of patients had TKD mutations.

Patients received standard induction chemotherapy, with daunorubicine and cytarabine, and on days 8 through 21 either 50 mg of midostaurin or placebo orally twice a day. Patients were given an identical second cycle of induction therapy, with midostaurin or placebo, if they showed definitive clinically significant residual leukemia after the first induction treatment.

Those who achieved complete remission after induction were given 4, 28-day cycles of consolidation treatment, with midostaurin or placebo on days 8 through 21. If they stayed in remission after that, they were given maintenance of 12, 28-day cycles of midostaurin or placebo.

They were not required to receive hematopoetic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), but it was performed at investigator discretion.

Midostaurin improved survival but not rates of complete remission as defined in the trial protocol, researchers reported.

The hazard ratio for death in the midostaurin group was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.96; one-sided P = .0009). The 4-year overall survival rate was 51.4% for the midostaurin group and 44.3% for the placebo group. Midostaurin was shown to benefit all mutation subgroups, but with no greater benefit in one group than another.

Patients in the midostaurin group had a 21.6% lower likelihood of having an event, defined as failure to achieve protocol-defined complete remission, relapse or death without relapse.

There was no significant difference between the groups in complete remission, which under protocol had to occur by day 60.

HSCT was performed in 57% of patients – during the first complete remission in 28.1% of the midostaurin group and in 22.7% during the first complete remission in the placebo group. For those who were transplanted after the first complete remission, no treatment effect was seen.

Researchers noted that there was a therapeutic benefit even among patients with ITD mutations but with a low allelic burden, in whom the disease might be due largely to mutations other than FLT3.

“It is possible that the benefit of midostaurin, which is a multitargeted kinase inhibitor, might lie beyond its ability to inhibit FLT3,” possibly through inhibition of KIT, researchers said.

They also noted that as the trial went on, more and more investigators decided to treat patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, based on newly reported data elsewhere. Since midostaurin was discontinued at the time of transplant, that could have limited exposure to the drug and limited its effect.

*CORRECTION 7/5/2017: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of patients in the placebo group as well as where the study originally appeared.

FROM NEJM

Key clinical point: Multitargeted kinase inhibitor midostaurin combined with standard chemotherapy improved survival in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia patients.

Major finding: The 4-year overall survival rate was 51.4% for the midostaurin group and 44.3% for the placebo group. Midostaurin was shown to benefit all mutation subgroups — internal tandem mutations and point mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain – but with no greater benefit in one group than another.

Data source: A multicenter, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by the National Cancer Institute and Novartis. Researchers reported receiving personal fees from Novartis and other companies.

Gilteritinib shows safety, efficacy in relapsed/refractory AML

Gilteritinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, had a generally favorable safety profile and inhibited FLT3 in a population enriched with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients who had the target mutations, based on results of a phase I/II trial.

The findings represent a step forward in treatment of AML with FLT3 inhibition, according to Alexander E. Perl, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Comprehensive Cancer Center, Philadelphia, and his colleagues in the trial (NCT02014558), which is sponsored by Astellas Pharma Global Development.

Gilteritinib at 120 mg/day is being tested in phase III trials and in combination with chemotherapy regimens.

Initial entrants in the FLT3 inhibitor class had poor bioavailability, lacked potency and kinase specificity, and had low rates of response. While newer FLT3 inhibitors have had more potent effects, the proportions of patients who have responded have varied and their responses have often been transient, with resistance emerging within a few weeks of treatment.

Gilteritinib is attractive because it has in vitro activity against FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations and tyrosine kinase domain mutations.

In the first-in-human, single-arm, open-label study — conducted at centers in the United States, Germany, France, and Italy — 252 patients were given one of seven gilteritinib doses, from 20 to 450 mg per day, either as part of a cohort to assess dose escalation or to expand a given dose.

FTL3 mutations were not required for study enrollment, but researchers did require 10 or more patients with confirmed FLT3 mutations to be enrolled in each of the dose expansion groups. Because they found that patients with the mutations were responding so much better than those with wild-type FLT3, they expanded the 120-mg and 200-mg dose cohorts to include only those with FLT3 mutations. In the end, 162 of 252 treated patients had internal tandem duplication mutations, 12 had codon D835 mutations, and 15 had both.

The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events, regardless of relation to treatment, were neutropenia, seen in 39%, anemia (24%), thrombocytopenia (13%), sepsis (11%), and pneumonia (11%).

Commonly reported treatment-related adverse events were diarrhea (37%), anemia (34%), fatigue (33%), elevated aspartate aminotransferase (26%), and elevated alanine aminotransferase (19%).

Serious adverse events seen in at least 5% of patients included febrile neutropenia (39%; five cases of which were related to the treatment), progressive disease (17%), sepsis (14%; two of which were related to treatment), and pneumonia (11%), and acute renal failure (10%; five related to treatment), the researchers reported in The Lancet Oncology (doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30416-3).

Seven deaths were judged to be possibly or probably related to treatment, seen in the 20-mg, 80-mg, 120-mg, and 200-mg groups.

Of the 249 patients with data allowing a full analysis, 100 (40%) achieved a response, with 8% achieving a complete remission, 4% a complete remission with incomplete platelet recovery, 18% a complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery, and 10% a partial remission.

At least 90% of the FLT3 inhibition was seen by the eighth day of treatment among those getting at least the 80-mg dose.

Median overall survival was 25 weeks, and leukemia-free survival will be reported in future data analyses, researchers said.

Only 19% of the patients with FLT3 mutations underwent a hematopoetic stem cell transplant after treatment, which was attributed in part to prior hematopioetic stem cell transplant and the advanced age of many of the patients. Among the patients who subsequently had transplants, the results did not have much effect. Median survival was 47 weeks for those with mutations who had an overall response to gilteritinib and had a transplant after treatment, compared to 42 weeks for those with mutations and an overall response but didn’t go on to transplant.

“Because gilteritinib as a single agent is likely to have limited curative capacity, even when used early in the disease course,” researchers wrote, “studies that integrate gilteritnib into frontline chemotherapy regimens are underway.”

Study authors reported receiving fees, grants, or nonfinancial support from Astellas, the sponsor of the trial, and other pharmaceutical companies.

Gilteritinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, had a generally favorable safety profile and inhibited FLT3 in a population enriched with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients who had the target mutations, based on results of a phase I/II trial.

The findings represent a step forward in treatment of AML with FLT3 inhibition, according to Alexander E. Perl, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Comprehensive Cancer Center, Philadelphia, and his colleagues in the trial (NCT02014558), which is sponsored by Astellas Pharma Global Development.

Gilteritinib at 120 mg/day is being tested in phase III trials and in combination with chemotherapy regimens.

Initial entrants in the FLT3 inhibitor class had poor bioavailability, lacked potency and kinase specificity, and had low rates of response. While newer FLT3 inhibitors have had more potent effects, the proportions of patients who have responded have varied and their responses have often been transient, with resistance emerging within a few weeks of treatment.

Gilteritinib is attractive because it has in vitro activity against FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations and tyrosine kinase domain mutations.

In the first-in-human, single-arm, open-label study — conducted at centers in the United States, Germany, France, and Italy — 252 patients were given one of seven gilteritinib doses, from 20 to 450 mg per day, either as part of a cohort to assess dose escalation or to expand a given dose.

FTL3 mutations were not required for study enrollment, but researchers did require 10 or more patients with confirmed FLT3 mutations to be enrolled in each of the dose expansion groups. Because they found that patients with the mutations were responding so much better than those with wild-type FLT3, they expanded the 120-mg and 200-mg dose cohorts to include only those with FLT3 mutations. In the end, 162 of 252 treated patients had internal tandem duplication mutations, 12 had codon D835 mutations, and 15 had both.

The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events, regardless of relation to treatment, were neutropenia, seen in 39%, anemia (24%), thrombocytopenia (13%), sepsis (11%), and pneumonia (11%).

Commonly reported treatment-related adverse events were diarrhea (37%), anemia (34%), fatigue (33%), elevated aspartate aminotransferase (26%), and elevated alanine aminotransferase (19%).

Serious adverse events seen in at least 5% of patients included febrile neutropenia (39%; five cases of which were related to the treatment), progressive disease (17%), sepsis (14%; two of which were related to treatment), and pneumonia (11%), and acute renal failure (10%; five related to treatment), the researchers reported in The Lancet Oncology (doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30416-3).

Seven deaths were judged to be possibly or probably related to treatment, seen in the 20-mg, 80-mg, 120-mg, and 200-mg groups.

Of the 249 patients with data allowing a full analysis, 100 (40%) achieved a response, with 8% achieving a complete remission, 4% a complete remission with incomplete platelet recovery, 18% a complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery, and 10% a partial remission.

At least 90% of the FLT3 inhibition was seen by the eighth day of treatment among those getting at least the 80-mg dose.

Median overall survival was 25 weeks, and leukemia-free survival will be reported in future data analyses, researchers said.

Only 19% of the patients with FLT3 mutations underwent a hematopoetic stem cell transplant after treatment, which was attributed in part to prior hematopioetic stem cell transplant and the advanced age of many of the patients. Among the patients who subsequently had transplants, the results did not have much effect. Median survival was 47 weeks for those with mutations who had an overall response to gilteritinib and had a transplant after treatment, compared to 42 weeks for those with mutations and an overall response but didn’t go on to transplant.

“Because gilteritinib as a single agent is likely to have limited curative capacity, even when used early in the disease course,” researchers wrote, “studies that integrate gilteritnib into frontline chemotherapy regimens are underway.”

Study authors reported receiving fees, grants, or nonfinancial support from Astellas, the sponsor of the trial, and other pharmaceutical companies.

Gilteritinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, had a generally favorable safety profile and inhibited FLT3 in a population enriched with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients who had the target mutations, based on results of a phase I/II trial.

The findings represent a step forward in treatment of AML with FLT3 inhibition, according to Alexander E. Perl, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Comprehensive Cancer Center, Philadelphia, and his colleagues in the trial (NCT02014558), which is sponsored by Astellas Pharma Global Development.

Gilteritinib at 120 mg/day is being tested in phase III trials and in combination with chemotherapy regimens.

Initial entrants in the FLT3 inhibitor class had poor bioavailability, lacked potency and kinase specificity, and had low rates of response. While newer FLT3 inhibitors have had more potent effects, the proportions of patients who have responded have varied and their responses have often been transient, with resistance emerging within a few weeks of treatment.

Gilteritinib is attractive because it has in vitro activity against FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations and tyrosine kinase domain mutations.

In the first-in-human, single-arm, open-label study — conducted at centers in the United States, Germany, France, and Italy — 252 patients were given one of seven gilteritinib doses, from 20 to 450 mg per day, either as part of a cohort to assess dose escalation or to expand a given dose.

FTL3 mutations were not required for study enrollment, but researchers did require 10 or more patients with confirmed FLT3 mutations to be enrolled in each of the dose expansion groups. Because they found that patients with the mutations were responding so much better than those with wild-type FLT3, they expanded the 120-mg and 200-mg dose cohorts to include only those with FLT3 mutations. In the end, 162 of 252 treated patients had internal tandem duplication mutations, 12 had codon D835 mutations, and 15 had both.

The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events, regardless of relation to treatment, were neutropenia, seen in 39%, anemia (24%), thrombocytopenia (13%), sepsis (11%), and pneumonia (11%).

Commonly reported treatment-related adverse events were diarrhea (37%), anemia (34%), fatigue (33%), elevated aspartate aminotransferase (26%), and elevated alanine aminotransferase (19%).

Serious adverse events seen in at least 5% of patients included febrile neutropenia (39%; five cases of which were related to the treatment), progressive disease (17%), sepsis (14%; two of which were related to treatment), and pneumonia (11%), and acute renal failure (10%; five related to treatment), the researchers reported in The Lancet Oncology (doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30416-3).

Seven deaths were judged to be possibly or probably related to treatment, seen in the 20-mg, 80-mg, 120-mg, and 200-mg groups.

Of the 249 patients with data allowing a full analysis, 100 (40%) achieved a response, with 8% achieving a complete remission, 4% a complete remission with incomplete platelet recovery, 18% a complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery, and 10% a partial remission.

At least 90% of the FLT3 inhibition was seen by the eighth day of treatment among those getting at least the 80-mg dose.

Median overall survival was 25 weeks, and leukemia-free survival will be reported in future data analyses, researchers said.

Only 19% of the patients with FLT3 mutations underwent a hematopoetic stem cell transplant after treatment, which was attributed in part to prior hematopioetic stem cell transplant and the advanced age of many of the patients. Among the patients who subsequently had transplants, the results did not have much effect. Median survival was 47 weeks for those with mutations who had an overall response to gilteritinib and had a transplant after treatment, compared to 42 weeks for those with mutations and an overall response but didn’t go on to transplant.

“Because gilteritinib as a single agent is likely to have limited curative capacity, even when used early in the disease course,” researchers wrote, “studies that integrate gilteritnib into frontline chemotherapy regimens are underway.”

Study authors reported receiving fees, grants, or nonfinancial support from Astellas, the sponsor of the trial, and other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: The highly selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor gilternitinib was generally safe and elicited responses in relapsed-refractory AML patients.

Major finding: Of the 249 patients with data allowing a full analysis, 100 (40%) achieved a response, with a median overall survival of 25 weeks.

Data source: Multicenter, single-arm, open-label study in Europe and the United States.

Disclosures: Astellas Pharma funded the study, and study authors reported receiving fees, grants or nonfinancial support from Astellas and other pharmaceutical companies.

Two SNPs linked to survival in R-CHOP–treated DLBCL

Two variations of the BCL2 gene are linked with the survival prospects of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who are treated with the R-CHOP regimen, based on a study published in Haematologica.

In the population-based, case-control study of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma across the British Columbia province, Morteza Bashash, PhD, of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, and researchers at the British Columbia Cancer Agency analyzed 217 germline DLBCL samples, excluding those with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, specifically looking at nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Patients receiving R-CHOP who had the AA genotype at rs7226979 had a risk of death that was four times higher than that of those with a G allele, researchers said (P less than .01). The same pattern was seen for PFS, with AA carriers having twice the risk of an event, compared with the other genotypes (P less than .05).

For those with rs4456611, patients with the GG genotype had a risk of death that was 3 times greater than that of those with an A allele (P less than .01), but there was no association with PFS for that SNP.

In an analysis of an independent cohort, only the associations that were seen with rs7226979 – and not those with rs4456611 – were able to be replicated.

The researchers noted that, while most predictive markers that are used to guide clinical treatment are drawn from actual tumor material, host-related factors could also be important.

“Compared to genetic analysis of the tumor, the patient’s constitutional genetic profile is relatively easy to obtain and can be assessed before treatment is started,” they wrote. “Our result has the potential to be useful as a complementary tool to predict the outcome of patients treated with R-CHOP and enhance clinical decision-making after confirmation by further studies.”

Two variations of the BCL2 gene are linked with the survival prospects of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who are treated with the R-CHOP regimen, based on a study published in Haematologica.

In the population-based, case-control study of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma across the British Columbia province, Morteza Bashash, PhD, of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, and researchers at the British Columbia Cancer Agency analyzed 217 germline DLBCL samples, excluding those with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, specifically looking at nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Patients receiving R-CHOP who had the AA genotype at rs7226979 had a risk of death that was four times higher than that of those with a G allele, researchers said (P less than .01). The same pattern was seen for PFS, with AA carriers having twice the risk of an event, compared with the other genotypes (P less than .05).

For those with rs4456611, patients with the GG genotype had a risk of death that was 3 times greater than that of those with an A allele (P less than .01), but there was no association with PFS for that SNP.

In an analysis of an independent cohort, only the associations that were seen with rs7226979 – and not those with rs4456611 – were able to be replicated.

The researchers noted that, while most predictive markers that are used to guide clinical treatment are drawn from actual tumor material, host-related factors could also be important.

“Compared to genetic analysis of the tumor, the patient’s constitutional genetic profile is relatively easy to obtain and can be assessed before treatment is started,” they wrote. “Our result has the potential to be useful as a complementary tool to predict the outcome of patients treated with R-CHOP and enhance clinical decision-making after confirmation by further studies.”

Two variations of the BCL2 gene are linked with the survival prospects of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who are treated with the R-CHOP regimen, based on a study published in Haematologica.

In the population-based, case-control study of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma across the British Columbia province, Morteza Bashash, PhD, of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, and researchers at the British Columbia Cancer Agency analyzed 217 germline DLBCL samples, excluding those with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, specifically looking at nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Patients receiving R-CHOP who had the AA genotype at rs7226979 had a risk of death that was four times higher than that of those with a G allele, researchers said (P less than .01). The same pattern was seen for PFS, with AA carriers having twice the risk of an event, compared with the other genotypes (P less than .05).

For those with rs4456611, patients with the GG genotype had a risk of death that was 3 times greater than that of those with an A allele (P less than .01), but there was no association with PFS for that SNP.

In an analysis of an independent cohort, only the associations that were seen with rs7226979 – and not those with rs4456611 – were able to be replicated.

The researchers noted that, while most predictive markers that are used to guide clinical treatment are drawn from actual tumor material, host-related factors could also be important.

“Compared to genetic analysis of the tumor, the patient’s constitutional genetic profile is relatively easy to obtain and can be assessed before treatment is started,” they wrote. “Our result has the potential to be useful as a complementary tool to predict the outcome of patients treated with R-CHOP and enhance clinical decision-making after confirmation by further studies.”

FROM HAEMATOLOGICA

Key clinical point: Two SNPs were found to be linked to survival prospects in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who receive primary R-CHOP therapy.

Major finding: For the rs7226979 SNP, those with the AA genotype had a four times higher risk of death than those with a G allele.

Data source: A population-based, case-control study of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in British Columbia, with DNA samples analyzed for 9nine SNPs among the DLBCL patients, excluding those with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma.

Disclosures: Some of the study authors reported institutional research funding from Roche; honoraria from Roche/Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Celgene; and/or consultant or advisory roles with Roche/Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, and NanoString Technologies.

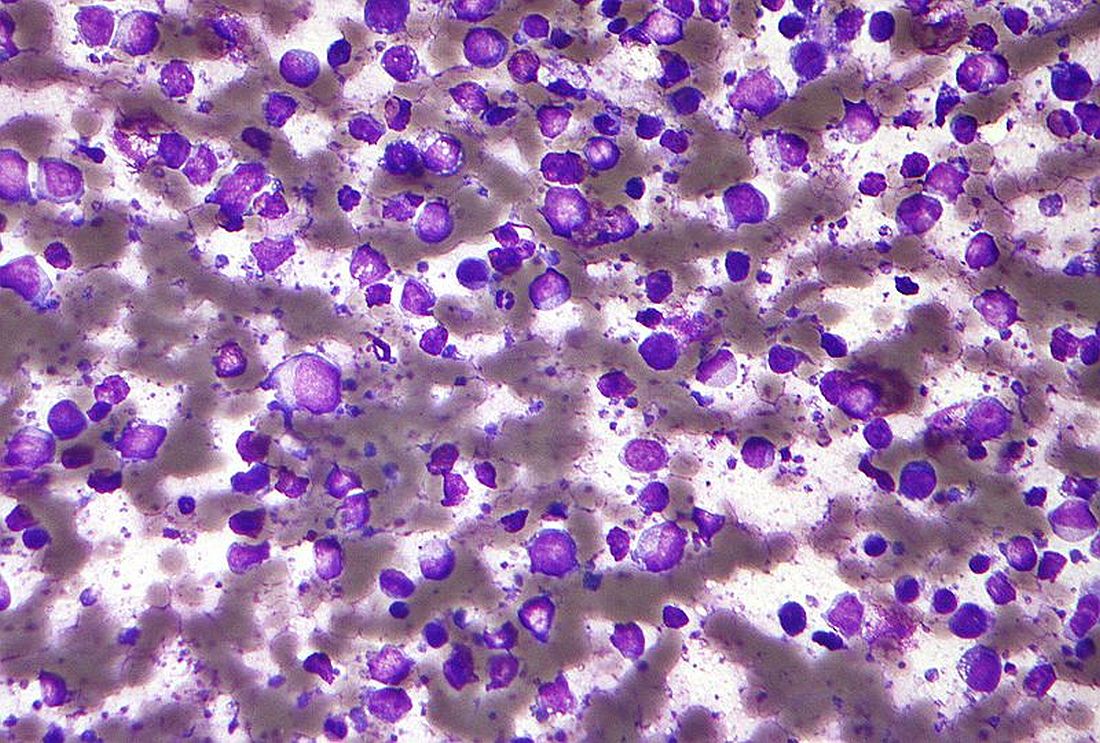

Liposomes boost bortezomib efficacy

Bortezomib treatment using liposome nanocarriers leads to decreased cell viability and greater apoptosis in vitro, compared with treatment with free bortezomib, according to a study in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Pharmacology.

Liposomes are lipid sacs with a watery compartment, which can be used to encapsulate and deliver a therapeutic cargo. The delivery method has been found to have improved efficacy with lesser side effects.

Ceramide liposomes are an attractive drug-delivery vehicle, the researchers said, because of their cell-permeability and because they’ve been found, on their own, to mediate apoptosis. Researchers said they believed this was the first time results have been reported on combining ceramide liposomes with an anticancer drug such as bortezomib. Cationic liposomes were picked because they’re known to destabilize cell membranes, helping with intracellular delivery of the drug.

Free bortezomib and bortezomib loaded into liposomes were tested for efficacy on mouse preosteoclast calvaria MC3T3 cells, mouse macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells, and human osteosarcoma U2OS cells.

On the RAW 264.7 cells, researchers found a significant difference in cell viability between free bortezomib and ceramide liposomes after 24 hours (P less than .01) and 48 hours (P less than .05) and between free bortezomib and cationic liposomes at 24 hours (P less than .01). They also reported a significant difference with cationic liposomes on MC3T3 cells and U2OS cells at 48 hours (both P less than .01).

One nanomolar (nM) of ceramide-loaded bortezomib induced significantly more apoptosis than did 1 nM of free bortezomib (P less than .01), and 10 nM of ceramide-loaded bortezomib brought about more cell death and apoptosis than did 10 nM of free bortezomib (P less than .05). These effects were likely the result of increased expression of proteins involved in apoptosis.

Liposomes might be able to boost the efficacy of bortezomib, according to the researchers, who are now studying the localization of these liposomes with confocal microscopes to better understand the mechanism of action.

“Such improvements,” they wrote, “offer the potential to reduce side effects known to occur with this chemotherapy, such as peripheral neuropathy, as well as to target Bort-resistant cancers.”

Bortezomib treatment using liposome nanocarriers leads to decreased cell viability and greater apoptosis in vitro, compared with treatment with free bortezomib, according to a study in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Pharmacology.

Liposomes are lipid sacs with a watery compartment, which can be used to encapsulate and deliver a therapeutic cargo. The delivery method has been found to have improved efficacy with lesser side effects.

Ceramide liposomes are an attractive drug-delivery vehicle, the researchers said, because of their cell-permeability and because they’ve been found, on their own, to mediate apoptosis. Researchers said they believed this was the first time results have been reported on combining ceramide liposomes with an anticancer drug such as bortezomib. Cationic liposomes were picked because they’re known to destabilize cell membranes, helping with intracellular delivery of the drug.

Free bortezomib and bortezomib loaded into liposomes were tested for efficacy on mouse preosteoclast calvaria MC3T3 cells, mouse macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells, and human osteosarcoma U2OS cells.

On the RAW 264.7 cells, researchers found a significant difference in cell viability between free bortezomib and ceramide liposomes after 24 hours (P less than .01) and 48 hours (P less than .05) and between free bortezomib and cationic liposomes at 24 hours (P less than .01). They also reported a significant difference with cationic liposomes on MC3T3 cells and U2OS cells at 48 hours (both P less than .01).

One nanomolar (nM) of ceramide-loaded bortezomib induced significantly more apoptosis than did 1 nM of free bortezomib (P less than .01), and 10 nM of ceramide-loaded bortezomib brought about more cell death and apoptosis than did 10 nM of free bortezomib (P less than .05). These effects were likely the result of increased expression of proteins involved in apoptosis.

Liposomes might be able to boost the efficacy of bortezomib, according to the researchers, who are now studying the localization of these liposomes with confocal microscopes to better understand the mechanism of action.

“Such improvements,” they wrote, “offer the potential to reduce side effects known to occur with this chemotherapy, such as peripheral neuropathy, as well as to target Bort-resistant cancers.”

Bortezomib treatment using liposome nanocarriers leads to decreased cell viability and greater apoptosis in vitro, compared with treatment with free bortezomib, according to a study in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Pharmacology.

Liposomes are lipid sacs with a watery compartment, which can be used to encapsulate and deliver a therapeutic cargo. The delivery method has been found to have improved efficacy with lesser side effects.

Ceramide liposomes are an attractive drug-delivery vehicle, the researchers said, because of their cell-permeability and because they’ve been found, on their own, to mediate apoptosis. Researchers said they believed this was the first time results have been reported on combining ceramide liposomes with an anticancer drug such as bortezomib. Cationic liposomes were picked because they’re known to destabilize cell membranes, helping with intracellular delivery of the drug.

Free bortezomib and bortezomib loaded into liposomes were tested for efficacy on mouse preosteoclast calvaria MC3T3 cells, mouse macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells, and human osteosarcoma U2OS cells.

On the RAW 264.7 cells, researchers found a significant difference in cell viability between free bortezomib and ceramide liposomes after 24 hours (P less than .01) and 48 hours (P less than .05) and between free bortezomib and cationic liposomes at 24 hours (P less than .01). They also reported a significant difference with cationic liposomes on MC3T3 cells and U2OS cells at 48 hours (both P less than .01).

One nanomolar (nM) of ceramide-loaded bortezomib induced significantly more apoptosis than did 1 nM of free bortezomib (P less than .01), and 10 nM of ceramide-loaded bortezomib brought about more cell death and apoptosis than did 10 nM of free bortezomib (P less than .05). These effects were likely the result of increased expression of proteins involved in apoptosis.

Liposomes might be able to boost the efficacy of bortezomib, according to the researchers, who are now studying the localization of these liposomes with confocal microscopes to better understand the mechanism of action.

“Such improvements,” they wrote, “offer the potential to reduce side effects known to occur with this chemotherapy, such as peripheral neuropathy, as well as to target Bort-resistant cancers.”

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES AND PHARMACOLOGY

Key clinical point: Ceramide and cationic liposomes loaded with bortezomib decreased cell viability and increased apoptosis in vitro, compared with bortezomib alone.

Major finding: One nanomolar (nM) of ceramide-loaded bortezomib induced significantly more apoptosis than did 1 nM of free bortezomib (P less than .01), and 10 nM of ceramide-loaded bortezomib brought about more cell death and apoptosis than did 10 nM of free bortezomib (P less than .05).

Data source: An in vitro study conducted at Midwestern University.

Disclosures: Researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

12 things pharmacists want hospitalists to know

It’s hard to rank anything in hospital medicine much higher than making sure patients receive the medications they need. When mistakes happen, the care is less than optimal, and, in the worst cases, there can be disastrous consequences. Yet, the pharmacy process – involving interplay between hospitalists and pharmacists – can sometimes be clunky and inefficient, even in the age of electronic health records (EHRs).

The Hospitalist surveyed a half-dozen experts, who touched on the need for extra vigilance, areas at high risk for miscues, ways to refine communications and, ultimately, how to improve the care of patients. The following are tips and helpful hints for front-line hospitalists caring for hospitalized patients.

1. Avoid assumptions and shortcuts when reviewing a patient’s home medication list.

“As the saying goes, ‘garbage in, garbage out.’ This applies to completing a comprehensive medication review for a patient at the time of admission to the hospital, to ensure the patient is started on the right medications,” said Lisa Kroon, PharmD, chair of the department of clinical pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco.

The EHR “is often more of a record of which medications have been ordered by a provider at some point,” she notes.

Doug Humber, PharmD, clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Diego, said hospitalists should be sure to ask patients about over-the-counter drugs, herbals, and nutraceuticals.

Dr. Kroon encourages hospitalists to conduct a complete medication review, which helps determine what should be continued at discharge.

“Sometimes, not all medications a patient was taking at home need to be restarted, such as vitamins or supplements, so avoid just entering, ‘Restart all home meds,’ ” she said.

2. Pay close attention to adjustments based on liver and kidney function.

“A hospitalist may take a more hands-off approach and just make the assumption that their medications are dose-adjusted appropriately, and I think that might be a bad assumption. [Don’t assume] that things are just automatically going to be adjusted,” Dr. Humber said.

That said, hospitalists also need to be cognizant of adjustments for reasons that aren’t kidney or liver related.

“It is well known that patients with renal and hepatic disease often require dosage adjustments for optimal therapeutic response, but patients with other characteristics and conditions also may require dosage adjustments due to variations in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics,” said Erika Thomas, MBA, RPh,, a pharmacist and director of the Inpatient Care Practitioners section of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. “Patients who are obese, elderly, neonatal, pediatric, and those with other comorbidities also may require dosage adjustment.”

Drug-drug interactions might call for unique dosage adjustments, too, she adds.

3. Carefully choose drug-information sources.

“Hospitalists can contact drug-information centers that answer complex clinical questions about drugs if they do not have the time to explore themselves,” he said.

Creighton University, Omaha, Neb., for example, has such a center that has been nationally recognized.

4. Carefully review patients’ medications when they transfer from different levels of care.

Certain medications are started in the ICU that may not need to be continued on the non-ICU floor or at discharge, said MacKenzie Clark, PharmD, program pharmacist at the University of California, San Francisco. One example is quetiapine, which is used in the ICU for delirium.

“Unfortunately, we are seeing patients erroneously continued on this [medication] on the floor. Some are even discharged on this [med],” Clark said, adding that a specific order set can be developed that has a 72-hour automatic stop date for all orders for quetiapine when used specifically for delirium.

“[The order set] can help reduce the chance that it be continued unnecessarily when a patient transfers out of the ICU,” she explains.

Another class of medication that is often initiated in the ICU is proton pump inhibitors for stress ulcer prophylaxis. Continuing these on the floor or at discharge, Clark said, should be carefully considered to avoid unnecessary use and potential adverse effects.

5. Seek opportunities to change from intravenous to oral medications – it could mean big savings.

Intravenous medications usually are more expensive than oral formulations. They also increase the risk of infection. Those are two good reasons to switch patients from IV to oral (PO) as early as possible.

“We find that physicians often don’t know how much drugs cost,” said Marilyn Stebbins, PharmD, vice chair of clinical innovation at University of California, San Francisco.

A common example, she said, is IV acetaminophen, the cost of which skyrocketed in 2014. Institutions can save significant dollars by limiting use of IV acetaminophen outside the perioperative area to patients unable to tolerate oral medications. For patients who are candidates for IV acetaminophen, consider setting an automatic expiration of the order at 24 hours.

Hospitalists can help reduce the drug budget by supporting IV-to-PO programs, in which pharmacists can automatically change an IV medication to PO formulation after verifying a patient is able to tolerate orals.

6. Consider a patient’s health insurance coverage when prescribing a drug at discharge.

“Don’t start the fancy drug that the patient can’t continue at home,” said Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist and health sciences clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego, and member of the UCSD pharmacy and therapeutics committee. “New anticoagulants are a great example. We run outpatient claims against their insurance before starting anything, as a policy to avoid this.”

7. Tell the pharmacist what you’re thinking.

Dr. Jenkins uses a case of sepsis as an example:

“If you make it clear that’s what’s happening, you can get a stat loading-dose infused and meet [The Joint Commission] goals for management and improve care, rather than just routine antibiotic starts,” he said.

“Why are you starting the anticoagulant? Recommendations could differ if it’s for acute PE (pulmonary embolism) versus just bridging, which pharmacists these days might catch as overtreatment,” he said. “Keep [the pharmacy] posted about upcoming changes, so they can do discharge planning and anticipate things like glucose management changes with steroid-dose fluctuations.”

8. Beware chronic medications that are not on the hospital formulary.

Your hospital likely has a formulary for chronic medications, such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and statins, which might be different than what the patient was taking at home. So, changes might need to be made, Dr. Clark.

“Pharmacists can assist in this,” she said. “Often, a ‘therapeutic interchange program’ can be established whereby a pharmacist can automatically change the medication to a therapeutically equivalent one and ensure the appropriate dose conversion.”

At discharge, the reverse process is required.

“Be sure you are not discharging the patient on the hospital formulary drug [e.g., ramipril] ... when they already have lisinopril in their medicine cabinet at home,” Clark said. “This can lead to confusion by the patient about which medication to take and result in unintended duplicate drug therapy or worse. A patient may not take either medication because they aren’t sure just what to take.”

9. Don’t hesitate to rely on pharmacists’ expertise.

“To ensure that patients enter and leave the hospital on the right medications and [that they are] taken at the right dose and time, do not forget to enlist your pharmacists to provide support during care transitions,” Dr. Stebbins said.

Dr. Humber said pharmacists are “uniquely qualified” to be medication experts in a facility, and that “kind of experience and that type of expertise to the care of the hospitalized patient is paramount.”

Dr. Thomas said that pharmacists can save hospitalists time.

“Check with your pharmacist on available decision-support tools, available infusion devices, institutional medication-related protocols, and medications within a drug class.”Additionally, encourage pharmacists to join you for rounds, if they’re not already doing so. Dr. Humber also said hospitalists should consider more one-on-one communications, noting that it’s always better to chat “face to face than it is over the phone or with a text message. Things can certainly get misinterpreted.”

10. Consider asking a pharmacist for advice on how to administer complicated regimens.

“Drugs can be administered in a variety of ways, including nasogastric, sublingual, oral, rectal, IV infusion, epidural, intra-arterial, topical, extracorporeal, and intrathecal,” Dr. Thomas said. “Not all drug formulations can be administered by all routes for a variety of reasons. Pharmacists can assist in determining the safest and most effective route of administration for drug formulations.”

11. Not all patients need broad-spectrum antibiotics for a prolonged period of time.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 20%-50% of all antibiotics prescribed in U.S. acute care hospitals are either unnecessary or inappropriate, Dr. Kroon said.

“Specifying the dose, duration, and indication for all courses of antibiotics helps promote the appropriate use of antibiotics,” she noted.

Pharmacists play a large role in antibiotic dosing based on therapeutic levels, such as with vancomycin or on organ function, as with renal dose-adjustments; and in identifying drug-drug interactions that occur frequently with antibiotics, such as with the separation of quinolones from many supplements.

12. When ordering medications, a complete and legible signature is required.

With new computerized physician order entry ordering, it seems intuitive that what a physician orders is what they want, Dr. Kroon said. But, if medication orders are not completely clear, errors can arise at steps in the medication management process, such as when a pharmacist verifies and approves the medication order or at medication administration by a nurse. To avoid errors, she suggests that every medication order have the drug name, dose, route, and frequency. She also suggested that all “PRN” – as needed – orders need an indication and additional specificity if there are multiple medications.

For pain medications, an example might be: “Tylenol 1,000 mg PO q8h prn mild pain; Norco 5-325mg, 1 tab PO q4h prn moderate pain; oxycodone 5mg PO q4h prn severe pain.” This, Dr. Kroon explains, allows nurses to know when a specific medication should be administered to a patient. “Writing complete orders alleviates unnecessary paging to the ordering providers and ensures the timely administration of medications to patients,” she said.

It’s hard to rank anything in hospital medicine much higher than making sure patients receive the medications they need. When mistakes happen, the care is less than optimal, and, in the worst cases, there can be disastrous consequences. Yet, the pharmacy process – involving interplay between hospitalists and pharmacists – can sometimes be clunky and inefficient, even in the age of electronic health records (EHRs).

The Hospitalist surveyed a half-dozen experts, who touched on the need for extra vigilance, areas at high risk for miscues, ways to refine communications and, ultimately, how to improve the care of patients. The following are tips and helpful hints for front-line hospitalists caring for hospitalized patients.

1. Avoid assumptions and shortcuts when reviewing a patient’s home medication list.

“As the saying goes, ‘garbage in, garbage out.’ This applies to completing a comprehensive medication review for a patient at the time of admission to the hospital, to ensure the patient is started on the right medications,” said Lisa Kroon, PharmD, chair of the department of clinical pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco.

The EHR “is often more of a record of which medications have been ordered by a provider at some point,” she notes.

Doug Humber, PharmD, clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Diego, said hospitalists should be sure to ask patients about over-the-counter drugs, herbals, and nutraceuticals.

Dr. Kroon encourages hospitalists to conduct a complete medication review, which helps determine what should be continued at discharge.

“Sometimes, not all medications a patient was taking at home need to be restarted, such as vitamins or supplements, so avoid just entering, ‘Restart all home meds,’ ” she said.

2. Pay close attention to adjustments based on liver and kidney function.

“A hospitalist may take a more hands-off approach and just make the assumption that their medications are dose-adjusted appropriately, and I think that might be a bad assumption. [Don’t assume] that things are just automatically going to be adjusted,” Dr. Humber said.

That said, hospitalists also need to be cognizant of adjustments for reasons that aren’t kidney or liver related.

“It is well known that patients with renal and hepatic disease often require dosage adjustments for optimal therapeutic response, but patients with other characteristics and conditions also may require dosage adjustments due to variations in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics,” said Erika Thomas, MBA, RPh,, a pharmacist and director of the Inpatient Care Practitioners section of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. “Patients who are obese, elderly, neonatal, pediatric, and those with other comorbidities also may require dosage adjustment.”

Drug-drug interactions might call for unique dosage adjustments, too, she adds.

3. Carefully choose drug-information sources.

“Hospitalists can contact drug-information centers that answer complex clinical questions about drugs if they do not have the time to explore themselves,” he said.

Creighton University, Omaha, Neb., for example, has such a center that has been nationally recognized.

4. Carefully review patients’ medications when they transfer from different levels of care.

Certain medications are started in the ICU that may not need to be continued on the non-ICU floor or at discharge, said MacKenzie Clark, PharmD, program pharmacist at the University of California, San Francisco. One example is quetiapine, which is used in the ICU for delirium.

“Unfortunately, we are seeing patients erroneously continued on this [medication] on the floor. Some are even discharged on this [med],” Clark said, adding that a specific order set can be developed that has a 72-hour automatic stop date for all orders for quetiapine when used specifically for delirium.

“[The order set] can help reduce the chance that it be continued unnecessarily when a patient transfers out of the ICU,” she explains.

Another class of medication that is often initiated in the ICU is proton pump inhibitors for stress ulcer prophylaxis. Continuing these on the floor or at discharge, Clark said, should be carefully considered to avoid unnecessary use and potential adverse effects.

5. Seek opportunities to change from intravenous to oral medications – it could mean big savings.

Intravenous medications usually are more expensive than oral formulations. They also increase the risk of infection. Those are two good reasons to switch patients from IV to oral (PO) as early as possible.

“We find that physicians often don’t know how much drugs cost,” said Marilyn Stebbins, PharmD, vice chair of clinical innovation at University of California, San Francisco.

A common example, she said, is IV acetaminophen, the cost of which skyrocketed in 2014. Institutions can save significant dollars by limiting use of IV acetaminophen outside the perioperative area to patients unable to tolerate oral medications. For patients who are candidates for IV acetaminophen, consider setting an automatic expiration of the order at 24 hours.

Hospitalists can help reduce the drug budget by supporting IV-to-PO programs, in which pharmacists can automatically change an IV medication to PO formulation after verifying a patient is able to tolerate orals.

6. Consider a patient’s health insurance coverage when prescribing a drug at discharge.

“Don’t start the fancy drug that the patient can’t continue at home,” said Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist and health sciences clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego, and member of the UCSD pharmacy and therapeutics committee. “New anticoagulants are a great example. We run outpatient claims against their insurance before starting anything, as a policy to avoid this.”

7. Tell the pharmacist what you’re thinking.

Dr. Jenkins uses a case of sepsis as an example:

“If you make it clear that’s what’s happening, you can get a stat loading-dose infused and meet [The Joint Commission] goals for management and improve care, rather than just routine antibiotic starts,” he said.

“Why are you starting the anticoagulant? Recommendations could differ if it’s for acute PE (pulmonary embolism) versus just bridging, which pharmacists these days might catch as overtreatment,” he said. “Keep [the pharmacy] posted about upcoming changes, so they can do discharge planning and anticipate things like glucose management changes with steroid-dose fluctuations.”

8. Beware chronic medications that are not on the hospital formulary.

Your hospital likely has a formulary for chronic medications, such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and statins, which might be different than what the patient was taking at home. So, changes might need to be made, Dr. Clark.

“Pharmacists can assist in this,” she said. “Often, a ‘therapeutic interchange program’ can be established whereby a pharmacist can automatically change the medication to a therapeutically equivalent one and ensure the appropriate dose conversion.”

At discharge, the reverse process is required.

“Be sure you are not discharging the patient on the hospital formulary drug [e.g., ramipril] ... when they already have lisinopril in their medicine cabinet at home,” Clark said. “This can lead to confusion by the patient about which medication to take and result in unintended duplicate drug therapy or worse. A patient may not take either medication because they aren’t sure just what to take.”

9. Don’t hesitate to rely on pharmacists’ expertise.

“To ensure that patients enter and leave the hospital on the right medications and [that they are] taken at the right dose and time, do not forget to enlist your pharmacists to provide support during care transitions,” Dr. Stebbins said.

Dr. Humber said pharmacists are “uniquely qualified” to be medication experts in a facility, and that “kind of experience and that type of expertise to the care of the hospitalized patient is paramount.”

Dr. Thomas said that pharmacists can save hospitalists time.

“Check with your pharmacist on available decision-support tools, available infusion devices, institutional medication-related protocols, and medications within a drug class.”Additionally, encourage pharmacists to join you for rounds, if they’re not already doing so. Dr. Humber also said hospitalists should consider more one-on-one communications, noting that it’s always better to chat “face to face than it is over the phone or with a text message. Things can certainly get misinterpreted.”

10. Consider asking a pharmacist for advice on how to administer complicated regimens.

“Drugs can be administered in a variety of ways, including nasogastric, sublingual, oral, rectal, IV infusion, epidural, intra-arterial, topical, extracorporeal, and intrathecal,” Dr. Thomas said. “Not all drug formulations can be administered by all routes for a variety of reasons. Pharmacists can assist in determining the safest and most effective route of administration for drug formulations.”

11. Not all patients need broad-spectrum antibiotics for a prolonged period of time.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 20%-50% of all antibiotics prescribed in U.S. acute care hospitals are either unnecessary or inappropriate, Dr. Kroon said.

“Specifying the dose, duration, and indication for all courses of antibiotics helps promote the appropriate use of antibiotics,” she noted.

Pharmacists play a large role in antibiotic dosing based on therapeutic levels, such as with vancomycin or on organ function, as with renal dose-adjustments; and in identifying drug-drug interactions that occur frequently with antibiotics, such as with the separation of quinolones from many supplements.

12. When ordering medications, a complete and legible signature is required.

With new computerized physician order entry ordering, it seems intuitive that what a physician orders is what they want, Dr. Kroon said. But, if medication orders are not completely clear, errors can arise at steps in the medication management process, such as when a pharmacist verifies and approves the medication order or at medication administration by a nurse. To avoid errors, she suggests that every medication order have the drug name, dose, route, and frequency. She also suggested that all “PRN” – as needed – orders need an indication and additional specificity if there are multiple medications.

For pain medications, an example might be: “Tylenol 1,000 mg PO q8h prn mild pain; Norco 5-325mg, 1 tab PO q4h prn moderate pain; oxycodone 5mg PO q4h prn severe pain.” This, Dr. Kroon explains, allows nurses to know when a specific medication should be administered to a patient. “Writing complete orders alleviates unnecessary paging to the ordering providers and ensures the timely administration of medications to patients,” she said.

It’s hard to rank anything in hospital medicine much higher than making sure patients receive the medications they need. When mistakes happen, the care is less than optimal, and, in the worst cases, there can be disastrous consequences. Yet, the pharmacy process – involving interplay between hospitalists and pharmacists – can sometimes be clunky and inefficient, even in the age of electronic health records (EHRs).

The Hospitalist surveyed a half-dozen experts, who touched on the need for extra vigilance, areas at high risk for miscues, ways to refine communications and, ultimately, how to improve the care of patients. The following are tips and helpful hints for front-line hospitalists caring for hospitalized patients.

1. Avoid assumptions and shortcuts when reviewing a patient’s home medication list.

“As the saying goes, ‘garbage in, garbage out.’ This applies to completing a comprehensive medication review for a patient at the time of admission to the hospital, to ensure the patient is started on the right medications,” said Lisa Kroon, PharmD, chair of the department of clinical pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco.

The EHR “is often more of a record of which medications have been ordered by a provider at some point,” she notes.

Doug Humber, PharmD, clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Diego, said hospitalists should be sure to ask patients about over-the-counter drugs, herbals, and nutraceuticals.

Dr. Kroon encourages hospitalists to conduct a complete medication review, which helps determine what should be continued at discharge.

“Sometimes, not all medications a patient was taking at home need to be restarted, such as vitamins or supplements, so avoid just entering, ‘Restart all home meds,’ ” she said.

2. Pay close attention to adjustments based on liver and kidney function.

“A hospitalist may take a more hands-off approach and just make the assumption that their medications are dose-adjusted appropriately, and I think that might be a bad assumption. [Don’t assume] that things are just automatically going to be adjusted,” Dr. Humber said.

That said, hospitalists also need to be cognizant of adjustments for reasons that aren’t kidney or liver related.

“It is well known that patients with renal and hepatic disease often require dosage adjustments for optimal therapeutic response, but patients with other characteristics and conditions also may require dosage adjustments due to variations in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics,” said Erika Thomas, MBA, RPh,, a pharmacist and director of the Inpatient Care Practitioners section of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. “Patients who are obese, elderly, neonatal, pediatric, and those with other comorbidities also may require dosage adjustment.”

Drug-drug interactions might call for unique dosage adjustments, too, she adds.

3. Carefully choose drug-information sources.

“Hospitalists can contact drug-information centers that answer complex clinical questions about drugs if they do not have the time to explore themselves,” he said.

Creighton University, Omaha, Neb., for example, has such a center that has been nationally recognized.

4. Carefully review patients’ medications when they transfer from different levels of care.

Certain medications are started in the ICU that may not need to be continued on the non-ICU floor or at discharge, said MacKenzie Clark, PharmD, program pharmacist at the University of California, San Francisco. One example is quetiapine, which is used in the ICU for delirium.

“Unfortunately, we are seeing patients erroneously continued on this [medication] on the floor. Some are even discharged on this [med],” Clark said, adding that a specific order set can be developed that has a 72-hour automatic stop date for all orders for quetiapine when used specifically for delirium.

“[The order set] can help reduce the chance that it be continued unnecessarily when a patient transfers out of the ICU,” she explains.

Another class of medication that is often initiated in the ICU is proton pump inhibitors for stress ulcer prophylaxis. Continuing these on the floor or at discharge, Clark said, should be carefully considered to avoid unnecessary use and potential adverse effects.

5. Seek opportunities to change from intravenous to oral medications – it could mean big savings.

Intravenous medications usually are more expensive than oral formulations. They also increase the risk of infection. Those are two good reasons to switch patients from IV to oral (PO) as early as possible.

“We find that physicians often don’t know how much drugs cost,” said Marilyn Stebbins, PharmD, vice chair of clinical innovation at University of California, San Francisco.

A common example, she said, is IV acetaminophen, the cost of which skyrocketed in 2014. Institutions can save significant dollars by limiting use of IV acetaminophen outside the perioperative area to patients unable to tolerate oral medications. For patients who are candidates for IV acetaminophen, consider setting an automatic expiration of the order at 24 hours.

Hospitalists can help reduce the drug budget by supporting IV-to-PO programs, in which pharmacists can automatically change an IV medication to PO formulation after verifying a patient is able to tolerate orals.

6. Consider a patient’s health insurance coverage when prescribing a drug at discharge.

“Don’t start the fancy drug that the patient can’t continue at home,” said Ian Jenkins, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist and health sciences clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego, and member of the UCSD pharmacy and therapeutics committee. “New anticoagulants are a great example. We run outpatient claims against their insurance before starting anything, as a policy to avoid this.”

7. Tell the pharmacist what you’re thinking.

Dr. Jenkins uses a case of sepsis as an example:

“If you make it clear that’s what’s happening, you can get a stat loading-dose infused and meet [The Joint Commission] goals for management and improve care, rather than just routine antibiotic starts,” he said.

“Why are you starting the anticoagulant? Recommendations could differ if it’s for acute PE (pulmonary embolism) versus just bridging, which pharmacists these days might catch as overtreatment,” he said. “Keep [the pharmacy] posted about upcoming changes, so they can do discharge planning and anticipate things like glucose management changes with steroid-dose fluctuations.”

8. Beware chronic medications that are not on the hospital formulary.

Your hospital likely has a formulary for chronic medications, such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and statins, which might be different than what the patient was taking at home. So, changes might need to be made, Dr. Clark.

“Pharmacists can assist in this,” she said. “Often, a ‘therapeutic interchange program’ can be established whereby a pharmacist can automatically change the medication to a therapeutically equivalent one and ensure the appropriate dose conversion.”

At discharge, the reverse process is required.

“Be sure you are not discharging the patient on the hospital formulary drug [e.g., ramipril] ... when they already have lisinopril in their medicine cabinet at home,” Clark said. “This can lead to confusion by the patient about which medication to take and result in unintended duplicate drug therapy or worse. A patient may not take either medication because they aren’t sure just what to take.”

9. Don’t hesitate to rely on pharmacists’ expertise.

“To ensure that patients enter and leave the hospital on the right medications and [that they are] taken at the right dose and time, do not forget to enlist your pharmacists to provide support during care transitions,” Dr. Stebbins said.

Dr. Humber said pharmacists are “uniquely qualified” to be medication experts in a facility, and that “kind of experience and that type of expertise to the care of the hospitalized patient is paramount.”

Dr. Thomas said that pharmacists can save hospitalists time.