User login

UPDATE ON CERVICAL DISEASE

Over the past year, we have gained further insight into the efficacy and safety of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines; received new, practical cervical screening guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); and gathered further evidence that colposcopy is not as sensitive at detecting high-grade cervical disease as we once thought.

In this article, I describe each of these developments in depth.

Both HPV vaccines are safe and effective—

and both offer cross-protection

Lu B, Kumar A, Castellsague X, Giuliano AR. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic vaccines against cervical HPV infection and diseases among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):13.

HPV 16 accounts for about 55% of all cases of cervical cancer and HPV 18 for another 15%—and both HPV vaccines on the market provide coverage against these two types. Because vaccination stands to reduce the burden of cervical disease so dramatically, it behooves us to achieve the highest possible vaccination rate for girls and young women.

Regrettably, fewer than 40% of the eligible female population of the United States has received one or more injections of either the bivalent (HPV 16, 18) (Cervarix) or quadrivalent (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18) (Gardasil) vaccine—with the vaccination rate varying considerably by geographic location and socioeconomic status.1 Clearly, we have much work ahead of us to improve this rate.

What’s the big picture?

Each trial of the HPV vaccine to date has demonstrated high efficacy and safety. Drawing from the individual findings of these trials to develop a snapshot of overall efficacy

and safety has been difficult, however, owing to multiple clinical endpoints, differences in both the number of virus-like particle types and in the adjuvant used in each vaccine, variability of the populations, and different definitions of efficacy. These limitations have made it difficult for clinicians and patients to make an informed decision about which vaccine to choose.

To address these concerns, Lu and colleagues conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of seven unique randomized, controlled trials with a total enrollment of 44,141 females. Their goal: to assess the safety and efficacy of both vaccines against multiple virologic and clinical endpoints, including efficacy not only against the primary HPV vaccine types, but closely related types as well.

They focused on two groups of girls and women:

- The per protocol population (PPP) included females who were both DNA- and sero-negative to the HPV types contained in the vaccine at the start and end of the vaccination period. The PPP group received all three injections of the vaccine, with no protocol violations.

- The intention-to-treat cohort (ITT) included women and girls who had received one or more doses of the vaccine or placebo and who had follow-up data available, regardless of HPV status at enrollment.

The PPP more closely resembles the sexually naïve population that stands to benefit most from the full vaccination series, whereas the ITT is more similar to girls and women 18 to 26 years old who are seeking “catch-up” vaccination, most of them having initiated sexual activity or had less than perfect compliance with vaccination, or both.

In the ITT cohort, the pooled relative risk (RR) for HPV 16-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 2 or worse was 0.47, corresponding to a pooled efficacy of 53%, a statistically significant benefit. In the PPP, the RR was 0.04, corresponding to a pooled efficacy of 96% for HPV 16-related CIN 2+. The RR was similar for HPV 18 (TABLE). The reduction in CIN 1 for women not previously infected with either of these high-risk HPV types was also high—95% for HPV 16 and 97% for HPV 18.

Effect of HPV vaccination on high-grade cervical disease

| Group | Relative risk of CIN 2+ | Reduction in CIN 2+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HpV 16 | HpV 18 | HpV 16 | HpV 18 | |

| Intention to treat | 0.47 | 0.16 | 53% | 84% |

| Per protocol | 0.04 | 0.10 | 96% | 90% |

| CIN=cervical intraepithelial neoplasia SOURCE: Lu B, et al. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic vaccines against cervical HPV infection and diseases among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):13. | ||||

Vaccines offer cross-protection against 3 additional HPV types

The possibility that the HPV vaccines provide cross-protection against closely related HPV types has generated considerable interest. Lu and colleagues assessed cross-protection against 6-month persistent infection related to five HPV types:

- HPV 31—relative risk (RR) of 0.47 and 0.30 in the ITT and PPP cohorts, respectively

- HPV 45—RR of 0.50 and 0.42 in the ITT and PPP cohorts, respectively. There was significant heterogeneity between the trials in efficacy against persistent HPV 45 infection.

- HPV 33—RR of 0.65 and 0.57 in the ITT and PPP cohorts, respectively

- HPV 52 and 58—no statistically significant cross-protection.

Adverse events are minimal

The most common systemic vaccine-related adverse events reported in all the trials were headache and fatigue, which were noted in 50% to 60% of participants. The most common serious adverse events were abnormal pregnancy outcomes, such as birth defects and spontaneous abortion, but the RR of 1.0 for all serious adverse events suggests a statistically insignificant difference in the risk of serious adverse events between vaccine and control groups. These findings are consistent with the most recent review by the CDC and FDA (October 2010), which concluded that Gardasil is safe and effective for the prevention of the four types covered in the vaccine.2 CDC updates on safety do not yet include the bivalent vaccine because of its more recent release to the US market.

At every opportunity, encourage HPV vaccination for girls and women who are 9 to 26 years old.

New STD guidelines from the CDC include tips

on cervical cancer screening

Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110.

The CDC’s most recent sexually transmitted disease (STD) guidelines, released at the end of 2010, cover all sexually transmitted infections, including genital HPV infection. In general, the recommendations on cervical cancer screening are consistent with ACOG’s 2009 guidelines, which I discussed in the March 2010 Update on Cervical Disease. The CDC also offers concrete, useful suggestions on how to counsel patients who have genital warts or who test positive for an oncogenic strain of HPV. Although the guidelines are aimed at STD and public health clinics, they include many recommendations useful to all health care providers. For that reason, discussion of the highlights seems appropriate.

Like ACOG, CDC says screening should start at 21 years

Screening should begin when the patient is 21 years old and continue at 2-year intervals until she is 30 years old, at which time it should switch to every 3 years—provided she has had three consecutive normal Pap tests or one normal cotest (Pap and HPV test combined).

Because a woman may sometimes assume that she has undergone a Pap test by virtue of having had a pelvic examination, inaccuracies in self-reported screening intervals may arise. Therefore, it is imperative to devise a protocol for cervical cancer screening among women who do not have documentation, in their medical record, of a normal Pap test within the preceding 12 months. Although some women will undoubtedly undergo screening sooner than necessary, this approach will protect women lacking adequate documentation from being underscreened.

When to use the HPV test (and when to avoid it)

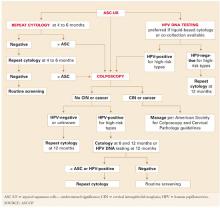

The guidelines confirm that the HPV test is an appropriate tool in the management of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC–US) among women 21 years and older and as a cotest with the Pap for women who are 30 years and older.

The CDC recommends against the HPV test in the following situations:

- when deciding whether to vaccinate against HPV

- as part of a screen for STD

- in the triage of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) Pap results, although 2006 guidelines from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and 2007 guidelines from ACOG recommend, as an option, the use of the HPV test in the triage of postmenopausal women who have LSIL

- in women younger than 21 years

- as a stand-alone primary cervical cancer screen (without the Pap test).

These recommendations are consistent with earlier conclusions.3

Perhaps the most important insights offered in the CDC’s 2010 STD guidelines are the counseling messages for women who undergo cotesting with both the HPV and Pap tests. It often is a challenge to communicate the indications for and findings of this screening approach. Here is guidance offered by the CDC:

- HPV is very common. It can infect the genital areas of both men and women. It usually has no signs or symptoms.

- Most sexually active persons get HPV at some time in their life, although few will ever know it. Even a person who has had only one lifetime sex partner can get HPV if the partner was infected.

- Although the immune system clears HPV infection most of the time, the infection fails to resolve in some people

- No clinically validated test exists for men to determine whether they have HPV infection. The most common manifestation of HPV infection in men is genital warts. High-risk HPV types seldom cause genital warts.

- Partners who are in a long-term relationship tend to share HPV. Sexual partners of HPV-infected people also likely have HPV, even though they may have no signs or symptoms of infection.

- Detection of high-risk HPV infection in a woman does not mean that she or her partner is engaging in sexual activity outside of a relationship. HPV infection can be present for many years before it is detected, and no method can accurately confirm when HPV infection was acquired.

The pap test is not a screening test for Std

Other findings that may be useful for all clinicians, as well as for those who practice in an STD clinic:

- The Pap test is not a screening test for STD

- All eligible women should undergo cervical cancer screening, regardless of sexual orientation (i.e., heterosexual, lesbian, or bisexual)

- Conventional cytology should be delayed if the patient is menstruating, and she should be advised to undergo a Pap test at the earliest opportunity

- If specific infections other than HPV are identified, the patient may need to undergo a repeat Pap test after appropriate treatment for those infections. However, in most instances, the Pap test will be reported as satisfactory for evaluation, and a reliable final report can be produced without the need to repeat the Pap test after treatment.

- The presence of a mucopurulent discharge should not delay the Pap test. The test can be performed after careful removal of the discharge with a saline-soaked cotton swab.

- When the Pap test is repeated because the previous test was interpreted as unsatisfactory, the patient should not be returned to regular screening intervals until the Pap test is reported as satisfactory and negative

- Cervical screening should not be accelerated for women who have genital warts and no other indication.

CDC recommendations on cervical cancer prevention and screening are consistent with those of other organizations, including ACOG. the counseling messages should be adopted universally.

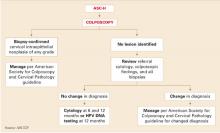

When colposcopic biopsy is indicated, take more than one sample

Stoler MH, Vichnin MD, Ferenczy A, et al; the FUTURE I, II and III Investigators. The accuracy of colposcopic biopsy: Analyses from the placebo arm of the Gardasil clinical trials. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(6):1354–1362.

The progress we have made in cervical cancer prevention is largely due to our ability to detect and treat precancer, particularly CIN 3, before it gains the capacity to invade. Until recently, few experts would have questioned the value of the partnership between cervical cytology screening and treatment of lesions detected on colposcopically directed biopsy.4 However, over the past decade, the accuracy of colposcopy for detection of high-grade lesions has been widely questioned, first by studies assessing static digitized cervigrams or colposcopy photo images, and more recently by studies comparing “real-time” colposcopy to histology obtained during colposcopy or excisional biopsy, or both.

The largest of these studies was conducted by Stoler and colleagues to compare the results of colposcopically directed biopsy and subsequent cervical excision among 737 women (16 to 45 years old) in the placebo arm of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (FUTURE) randomized, controlled trials. In these trials, all women were referred for colposcopy according to a Pap triage algorithm, and one or more biopsies was taken from the area with the greatest apparent abnormality, as viewed by colposcopy. When excisional treatment was indicated, a biopsy of the worst-appearing area was taken again just before the excision.

Each patient’s most severe pathology-panel diagnosis for the excisional specimen was compared with:

- the most severe biopsy result from the preceding 6 months (excluding the biopsy taken on the same day as the excisional procedure) (Analysis 1)

- the biopsy taken on the same day as the definitive excisional procedure (Analysis 2).

When CIN 2 and CIN 3 are managed similarly, a discrepancy of one degree between colposcopically directed biopsy and the excisional specimen is considered sufficient agreement. Therefore, in this study, a difference of one degree in histologic diagnosis was considered agreement.

High-grade disease was more likely to be underestimated

on the same-day biopsy

Colposcopically directed biopsies obtained within 6 months before definitive treatment (Analysis 1) had lower overall agreement with the excisional specimen than biopsies collected on the same day as definitive treatment (Analysis 2). However, underestimation of high-grade disease was lower (26% overall underestimation of CIN 2 or 3 or adenocarcinoma in situ [AIS]) on earlier biopsy specimens than on those collected on the same day as definitive treatment (57% overall underestimation of CIN 2 or 3 or AIS).

Conversely, overestimation, or removal, of disease was higher (36%) in biopsies collected within 6 months before the excisional treatment, compared with biopsies collected on the same day as definitive treatment (5%).

The investigators suggested that any discrepancy in accuracy between the biopsy obtained at treatment and the biopsy obtained earlier might be the result of less diligent colposcopic evaluation and biopsy placement when the colposcopist knew that definitive therapy would immediately follow. Another possibility, they noted, is that lesions biopsied as early as 6 months before definitive treatment may have regressed in the process of tissue repair or were completely removed by the biopsy.

When all biopsies were compared with the final diagnosis of the excisional specimen, the colposcopically directed biopsy was less severe 42% to 66% of the time when the excisional histology was read as CIN 3 or AIS. However, when one degree of discrepancy was allowed, as it is in clinical practice, agreement was 92%. This suggests that women in the FUTURE trials, as well as those in real clinical practice, are typically managed appropriately under current protocols that combine cytology and colposcopy results to properly identify women who have cervical lesions that require surgical intervention.

Most CIN 3 lesions were small

Many of the CIN 3 lesions in this trial were small, as they were in the ASCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS), in which the median length of CIN 3 lesions was only 6.5 mm. Also in ALTS, lesions in one third of patients were so small that colposcopically directed biopsy did not leave any residual disease to be detected in the loop electrosurgical excision specimen.5 The size of a CIN 3 lesion that has associated invasion is, on average, seven times larger than without invasion.6 Although colposcopy is much less likely to miss large lesions, it is important to miss as little high-grade disease as possible because the risk of invasion is cumulative over time and unpredictable in a given patient.

Multiple biopsies boost detection

Sampling more than one area improves the accuracy of colposcopically directed biopsy, even when one area looks most abnormal. This colposcopy photo shows potential biopsy sites (within the ovals), although other choices may also be reasonable. Several studies have shown that colposcopically directed biopsy of even normal-appearing areas at the squamocolumnar junction or within large ectopies can improve detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ.Studies have shown that it is possible to increase the accuracy of detection of CIN 2+ by increasing the number of biopsies. In this study by Stoler and colleagues, the sensitivity of initial colposcopy improved from 47% (for one biopsy) to 65% (two biopsies) and 77% (three or more) (FIGURE). Overall agreement increased with increasing age, which is consistent with the likelihood that CIN 3 lesions expand with age and become increasingly detectable by colposcopy.

Colposcopy does work, but the era of biopsying only the most abnormal-appearing area is over. Take more biopsies.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Pruitt SL, Schootman M. Geographic disparity, area poverty, and human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):525-533.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Frequently asked questions about HPV vaccine safety. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/Vaccines/HPV/hpv_faqs.html. Accessed February 1, 2011.

3. Cox JT, Moriarty AT, Castle PE. Commentary on: Statement on HPV DNA test utilization. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37(7):471-474.

4. Cox JT. More questions about the accuracy of colposcopy: what does this mean for cervical cancer prevention? Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1266-1267.

5. Sherman ME, Wang SS, Tarone R, Rich L, Schiffman M. Histopathologic extent of CIN 3 lesions in ALTS: implications for subject safety and lead-time bias. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(4):372-379.

6. Tidbury P, Singer A, Jenkins D. CIN 3: the role of lesion size in invasion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99(7):583-586.

Over the past year, we have gained further insight into the efficacy and safety of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines; received new, practical cervical screening guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); and gathered further evidence that colposcopy is not as sensitive at detecting high-grade cervical disease as we once thought.

In this article, I describe each of these developments in depth.

Both HPV vaccines are safe and effective—

and both offer cross-protection

Lu B, Kumar A, Castellsague X, Giuliano AR. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic vaccines against cervical HPV infection and diseases among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):13.

HPV 16 accounts for about 55% of all cases of cervical cancer and HPV 18 for another 15%—and both HPV vaccines on the market provide coverage against these two types. Because vaccination stands to reduce the burden of cervical disease so dramatically, it behooves us to achieve the highest possible vaccination rate for girls and young women.

Regrettably, fewer than 40% of the eligible female population of the United States has received one or more injections of either the bivalent (HPV 16, 18) (Cervarix) or quadrivalent (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18) (Gardasil) vaccine—with the vaccination rate varying considerably by geographic location and socioeconomic status.1 Clearly, we have much work ahead of us to improve this rate.

What’s the big picture?

Each trial of the HPV vaccine to date has demonstrated high efficacy and safety. Drawing from the individual findings of these trials to develop a snapshot of overall efficacy

and safety has been difficult, however, owing to multiple clinical endpoints, differences in both the number of virus-like particle types and in the adjuvant used in each vaccine, variability of the populations, and different definitions of efficacy. These limitations have made it difficult for clinicians and patients to make an informed decision about which vaccine to choose.

To address these concerns, Lu and colleagues conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of seven unique randomized, controlled trials with a total enrollment of 44,141 females. Their goal: to assess the safety and efficacy of both vaccines against multiple virologic and clinical endpoints, including efficacy not only against the primary HPV vaccine types, but closely related types as well.

They focused on two groups of girls and women:

- The per protocol population (PPP) included females who were both DNA- and sero-negative to the HPV types contained in the vaccine at the start and end of the vaccination period. The PPP group received all three injections of the vaccine, with no protocol violations.

- The intention-to-treat cohort (ITT) included women and girls who had received one or more doses of the vaccine or placebo and who had follow-up data available, regardless of HPV status at enrollment.

The PPP more closely resembles the sexually naïve population that stands to benefit most from the full vaccination series, whereas the ITT is more similar to girls and women 18 to 26 years old who are seeking “catch-up” vaccination, most of them having initiated sexual activity or had less than perfect compliance with vaccination, or both.

In the ITT cohort, the pooled relative risk (RR) for HPV 16-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 2 or worse was 0.47, corresponding to a pooled efficacy of 53%, a statistically significant benefit. In the PPP, the RR was 0.04, corresponding to a pooled efficacy of 96% for HPV 16-related CIN 2+. The RR was similar for HPV 18 (TABLE). The reduction in CIN 1 for women not previously infected with either of these high-risk HPV types was also high—95% for HPV 16 and 97% for HPV 18.

Effect of HPV vaccination on high-grade cervical disease

| Group | Relative risk of CIN 2+ | Reduction in CIN 2+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HpV 16 | HpV 18 | HpV 16 | HpV 18 | |

| Intention to treat | 0.47 | 0.16 | 53% | 84% |

| Per protocol | 0.04 | 0.10 | 96% | 90% |

| CIN=cervical intraepithelial neoplasia SOURCE: Lu B, et al. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic vaccines against cervical HPV infection and diseases among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):13. | ||||

Vaccines offer cross-protection against 3 additional HPV types

The possibility that the HPV vaccines provide cross-protection against closely related HPV types has generated considerable interest. Lu and colleagues assessed cross-protection against 6-month persistent infection related to five HPV types:

- HPV 31—relative risk (RR) of 0.47 and 0.30 in the ITT and PPP cohorts, respectively

- HPV 45—RR of 0.50 and 0.42 in the ITT and PPP cohorts, respectively. There was significant heterogeneity between the trials in efficacy against persistent HPV 45 infection.

- HPV 33—RR of 0.65 and 0.57 in the ITT and PPP cohorts, respectively

- HPV 52 and 58—no statistically significant cross-protection.

Adverse events are minimal

The most common systemic vaccine-related adverse events reported in all the trials were headache and fatigue, which were noted in 50% to 60% of participants. The most common serious adverse events were abnormal pregnancy outcomes, such as birth defects and spontaneous abortion, but the RR of 1.0 for all serious adverse events suggests a statistically insignificant difference in the risk of serious adverse events between vaccine and control groups. These findings are consistent with the most recent review by the CDC and FDA (October 2010), which concluded that Gardasil is safe and effective for the prevention of the four types covered in the vaccine.2 CDC updates on safety do not yet include the bivalent vaccine because of its more recent release to the US market.

At every opportunity, encourage HPV vaccination for girls and women who are 9 to 26 years old.

New STD guidelines from the CDC include tips

on cervical cancer screening

Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110.

The CDC’s most recent sexually transmitted disease (STD) guidelines, released at the end of 2010, cover all sexually transmitted infections, including genital HPV infection. In general, the recommendations on cervical cancer screening are consistent with ACOG’s 2009 guidelines, which I discussed in the March 2010 Update on Cervical Disease. The CDC also offers concrete, useful suggestions on how to counsel patients who have genital warts or who test positive for an oncogenic strain of HPV. Although the guidelines are aimed at STD and public health clinics, they include many recommendations useful to all health care providers. For that reason, discussion of the highlights seems appropriate.

Like ACOG, CDC says screening should start at 21 years

Screening should begin when the patient is 21 years old and continue at 2-year intervals until she is 30 years old, at which time it should switch to every 3 years—provided she has had three consecutive normal Pap tests or one normal cotest (Pap and HPV test combined).

Because a woman may sometimes assume that she has undergone a Pap test by virtue of having had a pelvic examination, inaccuracies in self-reported screening intervals may arise. Therefore, it is imperative to devise a protocol for cervical cancer screening among women who do not have documentation, in their medical record, of a normal Pap test within the preceding 12 months. Although some women will undoubtedly undergo screening sooner than necessary, this approach will protect women lacking adequate documentation from being underscreened.

When to use the HPV test (and when to avoid it)

The guidelines confirm that the HPV test is an appropriate tool in the management of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC–US) among women 21 years and older and as a cotest with the Pap for women who are 30 years and older.

The CDC recommends against the HPV test in the following situations:

- when deciding whether to vaccinate against HPV

- as part of a screen for STD

- in the triage of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) Pap results, although 2006 guidelines from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and 2007 guidelines from ACOG recommend, as an option, the use of the HPV test in the triage of postmenopausal women who have LSIL

- in women younger than 21 years

- as a stand-alone primary cervical cancer screen (without the Pap test).

These recommendations are consistent with earlier conclusions.3

Perhaps the most important insights offered in the CDC’s 2010 STD guidelines are the counseling messages for women who undergo cotesting with both the HPV and Pap tests. It often is a challenge to communicate the indications for and findings of this screening approach. Here is guidance offered by the CDC:

- HPV is very common. It can infect the genital areas of both men and women. It usually has no signs or symptoms.

- Most sexually active persons get HPV at some time in their life, although few will ever know it. Even a person who has had only one lifetime sex partner can get HPV if the partner was infected.

- Although the immune system clears HPV infection most of the time, the infection fails to resolve in some people

- No clinically validated test exists for men to determine whether they have HPV infection. The most common manifestation of HPV infection in men is genital warts. High-risk HPV types seldom cause genital warts.

- Partners who are in a long-term relationship tend to share HPV. Sexual partners of HPV-infected people also likely have HPV, even though they may have no signs or symptoms of infection.

- Detection of high-risk HPV infection in a woman does not mean that she or her partner is engaging in sexual activity outside of a relationship. HPV infection can be present for many years before it is detected, and no method can accurately confirm when HPV infection was acquired.

The pap test is not a screening test for Std

Other findings that may be useful for all clinicians, as well as for those who practice in an STD clinic:

- The Pap test is not a screening test for STD

- All eligible women should undergo cervical cancer screening, regardless of sexual orientation (i.e., heterosexual, lesbian, or bisexual)

- Conventional cytology should be delayed if the patient is menstruating, and she should be advised to undergo a Pap test at the earliest opportunity

- If specific infections other than HPV are identified, the patient may need to undergo a repeat Pap test after appropriate treatment for those infections. However, in most instances, the Pap test will be reported as satisfactory for evaluation, and a reliable final report can be produced without the need to repeat the Pap test after treatment.

- The presence of a mucopurulent discharge should not delay the Pap test. The test can be performed after careful removal of the discharge with a saline-soaked cotton swab.

- When the Pap test is repeated because the previous test was interpreted as unsatisfactory, the patient should not be returned to regular screening intervals until the Pap test is reported as satisfactory and negative

- Cervical screening should not be accelerated for women who have genital warts and no other indication.

CDC recommendations on cervical cancer prevention and screening are consistent with those of other organizations, including ACOG. the counseling messages should be adopted universally.

When colposcopic biopsy is indicated, take more than one sample

Stoler MH, Vichnin MD, Ferenczy A, et al; the FUTURE I, II and III Investigators. The accuracy of colposcopic biopsy: Analyses from the placebo arm of the Gardasil clinical trials. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(6):1354–1362.

The progress we have made in cervical cancer prevention is largely due to our ability to detect and treat precancer, particularly CIN 3, before it gains the capacity to invade. Until recently, few experts would have questioned the value of the partnership between cervical cytology screening and treatment of lesions detected on colposcopically directed biopsy.4 However, over the past decade, the accuracy of colposcopy for detection of high-grade lesions has been widely questioned, first by studies assessing static digitized cervigrams or colposcopy photo images, and more recently by studies comparing “real-time” colposcopy to histology obtained during colposcopy or excisional biopsy, or both.

The largest of these studies was conducted by Stoler and colleagues to compare the results of colposcopically directed biopsy and subsequent cervical excision among 737 women (16 to 45 years old) in the placebo arm of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (FUTURE) randomized, controlled trials. In these trials, all women were referred for colposcopy according to a Pap triage algorithm, and one or more biopsies was taken from the area with the greatest apparent abnormality, as viewed by colposcopy. When excisional treatment was indicated, a biopsy of the worst-appearing area was taken again just before the excision.

Each patient’s most severe pathology-panel diagnosis for the excisional specimen was compared with:

- the most severe biopsy result from the preceding 6 months (excluding the biopsy taken on the same day as the excisional procedure) (Analysis 1)

- the biopsy taken on the same day as the definitive excisional procedure (Analysis 2).

When CIN 2 and CIN 3 are managed similarly, a discrepancy of one degree between colposcopically directed biopsy and the excisional specimen is considered sufficient agreement. Therefore, in this study, a difference of one degree in histologic diagnosis was considered agreement.

High-grade disease was more likely to be underestimated

on the same-day biopsy

Colposcopically directed biopsies obtained within 6 months before definitive treatment (Analysis 1) had lower overall agreement with the excisional specimen than biopsies collected on the same day as definitive treatment (Analysis 2). However, underestimation of high-grade disease was lower (26% overall underestimation of CIN 2 or 3 or adenocarcinoma in situ [AIS]) on earlier biopsy specimens than on those collected on the same day as definitive treatment (57% overall underestimation of CIN 2 or 3 or AIS).

Conversely, overestimation, or removal, of disease was higher (36%) in biopsies collected within 6 months before the excisional treatment, compared with biopsies collected on the same day as definitive treatment (5%).

The investigators suggested that any discrepancy in accuracy between the biopsy obtained at treatment and the biopsy obtained earlier might be the result of less diligent colposcopic evaluation and biopsy placement when the colposcopist knew that definitive therapy would immediately follow. Another possibility, they noted, is that lesions biopsied as early as 6 months before definitive treatment may have regressed in the process of tissue repair or were completely removed by the biopsy.

When all biopsies were compared with the final diagnosis of the excisional specimen, the colposcopically directed biopsy was less severe 42% to 66% of the time when the excisional histology was read as CIN 3 or AIS. However, when one degree of discrepancy was allowed, as it is in clinical practice, agreement was 92%. This suggests that women in the FUTURE trials, as well as those in real clinical practice, are typically managed appropriately under current protocols that combine cytology and colposcopy results to properly identify women who have cervical lesions that require surgical intervention.

Most CIN 3 lesions were small

Many of the CIN 3 lesions in this trial were small, as they were in the ASCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS), in which the median length of CIN 3 lesions was only 6.5 mm. Also in ALTS, lesions in one third of patients were so small that colposcopically directed biopsy did not leave any residual disease to be detected in the loop electrosurgical excision specimen.5 The size of a CIN 3 lesion that has associated invasion is, on average, seven times larger than without invasion.6 Although colposcopy is much less likely to miss large lesions, it is important to miss as little high-grade disease as possible because the risk of invasion is cumulative over time and unpredictable in a given patient.

Multiple biopsies boost detection

Sampling more than one area improves the accuracy of colposcopically directed biopsy, even when one area looks most abnormal. This colposcopy photo shows potential biopsy sites (within the ovals), although other choices may also be reasonable. Several studies have shown that colposcopically directed biopsy of even normal-appearing areas at the squamocolumnar junction or within large ectopies can improve detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ.Studies have shown that it is possible to increase the accuracy of detection of CIN 2+ by increasing the number of biopsies. In this study by Stoler and colleagues, the sensitivity of initial colposcopy improved from 47% (for one biopsy) to 65% (two biopsies) and 77% (three or more) (FIGURE). Overall agreement increased with increasing age, which is consistent with the likelihood that CIN 3 lesions expand with age and become increasingly detectable by colposcopy.

Colposcopy does work, but the era of biopsying only the most abnormal-appearing area is over. Take more biopsies.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Over the past year, we have gained further insight into the efficacy and safety of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines; received new, practical cervical screening guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); and gathered further evidence that colposcopy is not as sensitive at detecting high-grade cervical disease as we once thought.

In this article, I describe each of these developments in depth.

Both HPV vaccines are safe and effective—

and both offer cross-protection

Lu B, Kumar A, Castellsague X, Giuliano AR. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic vaccines against cervical HPV infection and diseases among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):13.

HPV 16 accounts for about 55% of all cases of cervical cancer and HPV 18 for another 15%—and both HPV vaccines on the market provide coverage against these two types. Because vaccination stands to reduce the burden of cervical disease so dramatically, it behooves us to achieve the highest possible vaccination rate for girls and young women.

Regrettably, fewer than 40% of the eligible female population of the United States has received one or more injections of either the bivalent (HPV 16, 18) (Cervarix) or quadrivalent (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18) (Gardasil) vaccine—with the vaccination rate varying considerably by geographic location and socioeconomic status.1 Clearly, we have much work ahead of us to improve this rate.

What’s the big picture?

Each trial of the HPV vaccine to date has demonstrated high efficacy and safety. Drawing from the individual findings of these trials to develop a snapshot of overall efficacy

and safety has been difficult, however, owing to multiple clinical endpoints, differences in both the number of virus-like particle types and in the adjuvant used in each vaccine, variability of the populations, and different definitions of efficacy. These limitations have made it difficult for clinicians and patients to make an informed decision about which vaccine to choose.

To address these concerns, Lu and colleagues conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of seven unique randomized, controlled trials with a total enrollment of 44,141 females. Their goal: to assess the safety and efficacy of both vaccines against multiple virologic and clinical endpoints, including efficacy not only against the primary HPV vaccine types, but closely related types as well.

They focused on two groups of girls and women:

- The per protocol population (PPP) included females who were both DNA- and sero-negative to the HPV types contained in the vaccine at the start and end of the vaccination period. The PPP group received all three injections of the vaccine, with no protocol violations.

- The intention-to-treat cohort (ITT) included women and girls who had received one or more doses of the vaccine or placebo and who had follow-up data available, regardless of HPV status at enrollment.

The PPP more closely resembles the sexually naïve population that stands to benefit most from the full vaccination series, whereas the ITT is more similar to girls and women 18 to 26 years old who are seeking “catch-up” vaccination, most of them having initiated sexual activity or had less than perfect compliance with vaccination, or both.

In the ITT cohort, the pooled relative risk (RR) for HPV 16-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 2 or worse was 0.47, corresponding to a pooled efficacy of 53%, a statistically significant benefit. In the PPP, the RR was 0.04, corresponding to a pooled efficacy of 96% for HPV 16-related CIN 2+. The RR was similar for HPV 18 (TABLE). The reduction in CIN 1 for women not previously infected with either of these high-risk HPV types was also high—95% for HPV 16 and 97% for HPV 18.

Effect of HPV vaccination on high-grade cervical disease

| Group | Relative risk of CIN 2+ | Reduction in CIN 2+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HpV 16 | HpV 18 | HpV 16 | HpV 18 | |

| Intention to treat | 0.47 | 0.16 | 53% | 84% |

| Per protocol | 0.04 | 0.10 | 96% | 90% |

| CIN=cervical intraepithelial neoplasia SOURCE: Lu B, et al. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic vaccines against cervical HPV infection and diseases among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):13. | ||||

Vaccines offer cross-protection against 3 additional HPV types

The possibility that the HPV vaccines provide cross-protection against closely related HPV types has generated considerable interest. Lu and colleagues assessed cross-protection against 6-month persistent infection related to five HPV types:

- HPV 31—relative risk (RR) of 0.47 and 0.30 in the ITT and PPP cohorts, respectively

- HPV 45—RR of 0.50 and 0.42 in the ITT and PPP cohorts, respectively. There was significant heterogeneity between the trials in efficacy against persistent HPV 45 infection.

- HPV 33—RR of 0.65 and 0.57 in the ITT and PPP cohorts, respectively

- HPV 52 and 58—no statistically significant cross-protection.

Adverse events are minimal

The most common systemic vaccine-related adverse events reported in all the trials were headache and fatigue, which were noted in 50% to 60% of participants. The most common serious adverse events were abnormal pregnancy outcomes, such as birth defects and spontaneous abortion, but the RR of 1.0 for all serious adverse events suggests a statistically insignificant difference in the risk of serious adverse events between vaccine and control groups. These findings are consistent with the most recent review by the CDC and FDA (October 2010), which concluded that Gardasil is safe and effective for the prevention of the four types covered in the vaccine.2 CDC updates on safety do not yet include the bivalent vaccine because of its more recent release to the US market.

At every opportunity, encourage HPV vaccination for girls and women who are 9 to 26 years old.

New STD guidelines from the CDC include tips

on cervical cancer screening

Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110.

The CDC’s most recent sexually transmitted disease (STD) guidelines, released at the end of 2010, cover all sexually transmitted infections, including genital HPV infection. In general, the recommendations on cervical cancer screening are consistent with ACOG’s 2009 guidelines, which I discussed in the March 2010 Update on Cervical Disease. The CDC also offers concrete, useful suggestions on how to counsel patients who have genital warts or who test positive for an oncogenic strain of HPV. Although the guidelines are aimed at STD and public health clinics, they include many recommendations useful to all health care providers. For that reason, discussion of the highlights seems appropriate.

Like ACOG, CDC says screening should start at 21 years

Screening should begin when the patient is 21 years old and continue at 2-year intervals until she is 30 years old, at which time it should switch to every 3 years—provided she has had three consecutive normal Pap tests or one normal cotest (Pap and HPV test combined).

Because a woman may sometimes assume that she has undergone a Pap test by virtue of having had a pelvic examination, inaccuracies in self-reported screening intervals may arise. Therefore, it is imperative to devise a protocol for cervical cancer screening among women who do not have documentation, in their medical record, of a normal Pap test within the preceding 12 months. Although some women will undoubtedly undergo screening sooner than necessary, this approach will protect women lacking adequate documentation from being underscreened.

When to use the HPV test (and when to avoid it)

The guidelines confirm that the HPV test is an appropriate tool in the management of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC–US) among women 21 years and older and as a cotest with the Pap for women who are 30 years and older.

The CDC recommends against the HPV test in the following situations:

- when deciding whether to vaccinate against HPV

- as part of a screen for STD

- in the triage of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) Pap results, although 2006 guidelines from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and 2007 guidelines from ACOG recommend, as an option, the use of the HPV test in the triage of postmenopausal women who have LSIL

- in women younger than 21 years

- as a stand-alone primary cervical cancer screen (without the Pap test).

These recommendations are consistent with earlier conclusions.3

Perhaps the most important insights offered in the CDC’s 2010 STD guidelines are the counseling messages for women who undergo cotesting with both the HPV and Pap tests. It often is a challenge to communicate the indications for and findings of this screening approach. Here is guidance offered by the CDC:

- HPV is very common. It can infect the genital areas of both men and women. It usually has no signs or symptoms.

- Most sexually active persons get HPV at some time in their life, although few will ever know it. Even a person who has had only one lifetime sex partner can get HPV if the partner was infected.

- Although the immune system clears HPV infection most of the time, the infection fails to resolve in some people

- No clinically validated test exists for men to determine whether they have HPV infection. The most common manifestation of HPV infection in men is genital warts. High-risk HPV types seldom cause genital warts.

- Partners who are in a long-term relationship tend to share HPV. Sexual partners of HPV-infected people also likely have HPV, even though they may have no signs or symptoms of infection.

- Detection of high-risk HPV infection in a woman does not mean that she or her partner is engaging in sexual activity outside of a relationship. HPV infection can be present for many years before it is detected, and no method can accurately confirm when HPV infection was acquired.

The pap test is not a screening test for Std

Other findings that may be useful for all clinicians, as well as for those who practice in an STD clinic:

- The Pap test is not a screening test for STD

- All eligible women should undergo cervical cancer screening, regardless of sexual orientation (i.e., heterosexual, lesbian, or bisexual)

- Conventional cytology should be delayed if the patient is menstruating, and she should be advised to undergo a Pap test at the earliest opportunity

- If specific infections other than HPV are identified, the patient may need to undergo a repeat Pap test after appropriate treatment for those infections. However, in most instances, the Pap test will be reported as satisfactory for evaluation, and a reliable final report can be produced without the need to repeat the Pap test after treatment.

- The presence of a mucopurulent discharge should not delay the Pap test. The test can be performed after careful removal of the discharge with a saline-soaked cotton swab.

- When the Pap test is repeated because the previous test was interpreted as unsatisfactory, the patient should not be returned to regular screening intervals until the Pap test is reported as satisfactory and negative

- Cervical screening should not be accelerated for women who have genital warts and no other indication.

CDC recommendations on cervical cancer prevention and screening are consistent with those of other organizations, including ACOG. the counseling messages should be adopted universally.

When colposcopic biopsy is indicated, take more than one sample

Stoler MH, Vichnin MD, Ferenczy A, et al; the FUTURE I, II and III Investigators. The accuracy of colposcopic biopsy: Analyses from the placebo arm of the Gardasil clinical trials. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(6):1354–1362.

The progress we have made in cervical cancer prevention is largely due to our ability to detect and treat precancer, particularly CIN 3, before it gains the capacity to invade. Until recently, few experts would have questioned the value of the partnership between cervical cytology screening and treatment of lesions detected on colposcopically directed biopsy.4 However, over the past decade, the accuracy of colposcopy for detection of high-grade lesions has been widely questioned, first by studies assessing static digitized cervigrams or colposcopy photo images, and more recently by studies comparing “real-time” colposcopy to histology obtained during colposcopy or excisional biopsy, or both.

The largest of these studies was conducted by Stoler and colleagues to compare the results of colposcopically directed biopsy and subsequent cervical excision among 737 women (16 to 45 years old) in the placebo arm of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (FUTURE) randomized, controlled trials. In these trials, all women were referred for colposcopy according to a Pap triage algorithm, and one or more biopsies was taken from the area with the greatest apparent abnormality, as viewed by colposcopy. When excisional treatment was indicated, a biopsy of the worst-appearing area was taken again just before the excision.

Each patient’s most severe pathology-panel diagnosis for the excisional specimen was compared with:

- the most severe biopsy result from the preceding 6 months (excluding the biopsy taken on the same day as the excisional procedure) (Analysis 1)

- the biopsy taken on the same day as the definitive excisional procedure (Analysis 2).

When CIN 2 and CIN 3 are managed similarly, a discrepancy of one degree between colposcopically directed biopsy and the excisional specimen is considered sufficient agreement. Therefore, in this study, a difference of one degree in histologic diagnosis was considered agreement.

High-grade disease was more likely to be underestimated

on the same-day biopsy

Colposcopically directed biopsies obtained within 6 months before definitive treatment (Analysis 1) had lower overall agreement with the excisional specimen than biopsies collected on the same day as definitive treatment (Analysis 2). However, underestimation of high-grade disease was lower (26% overall underestimation of CIN 2 or 3 or adenocarcinoma in situ [AIS]) on earlier biopsy specimens than on those collected on the same day as definitive treatment (57% overall underestimation of CIN 2 or 3 or AIS).

Conversely, overestimation, or removal, of disease was higher (36%) in biopsies collected within 6 months before the excisional treatment, compared with biopsies collected on the same day as definitive treatment (5%).

The investigators suggested that any discrepancy in accuracy between the biopsy obtained at treatment and the biopsy obtained earlier might be the result of less diligent colposcopic evaluation and biopsy placement when the colposcopist knew that definitive therapy would immediately follow. Another possibility, they noted, is that lesions biopsied as early as 6 months before definitive treatment may have regressed in the process of tissue repair or were completely removed by the biopsy.

When all biopsies were compared with the final diagnosis of the excisional specimen, the colposcopically directed biopsy was less severe 42% to 66% of the time when the excisional histology was read as CIN 3 or AIS. However, when one degree of discrepancy was allowed, as it is in clinical practice, agreement was 92%. This suggests that women in the FUTURE trials, as well as those in real clinical practice, are typically managed appropriately under current protocols that combine cytology and colposcopy results to properly identify women who have cervical lesions that require surgical intervention.

Most CIN 3 lesions were small

Many of the CIN 3 lesions in this trial were small, as they were in the ASCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS), in which the median length of CIN 3 lesions was only 6.5 mm. Also in ALTS, lesions in one third of patients were so small that colposcopically directed biopsy did not leave any residual disease to be detected in the loop electrosurgical excision specimen.5 The size of a CIN 3 lesion that has associated invasion is, on average, seven times larger than without invasion.6 Although colposcopy is much less likely to miss large lesions, it is important to miss as little high-grade disease as possible because the risk of invasion is cumulative over time and unpredictable in a given patient.

Multiple biopsies boost detection

Sampling more than one area improves the accuracy of colposcopically directed biopsy, even when one area looks most abnormal. This colposcopy photo shows potential biopsy sites (within the ovals), although other choices may also be reasonable. Several studies have shown that colposcopically directed biopsy of even normal-appearing areas at the squamocolumnar junction or within large ectopies can improve detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ.Studies have shown that it is possible to increase the accuracy of detection of CIN 2+ by increasing the number of biopsies. In this study by Stoler and colleagues, the sensitivity of initial colposcopy improved from 47% (for one biopsy) to 65% (two biopsies) and 77% (three or more) (FIGURE). Overall agreement increased with increasing age, which is consistent with the likelihood that CIN 3 lesions expand with age and become increasingly detectable by colposcopy.

Colposcopy does work, but the era of biopsying only the most abnormal-appearing area is over. Take more biopsies.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Pruitt SL, Schootman M. Geographic disparity, area poverty, and human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):525-533.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Frequently asked questions about HPV vaccine safety. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/Vaccines/HPV/hpv_faqs.html. Accessed February 1, 2011.

3. Cox JT, Moriarty AT, Castle PE. Commentary on: Statement on HPV DNA test utilization. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37(7):471-474.

4. Cox JT. More questions about the accuracy of colposcopy: what does this mean for cervical cancer prevention? Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1266-1267.

5. Sherman ME, Wang SS, Tarone R, Rich L, Schiffman M. Histopathologic extent of CIN 3 lesions in ALTS: implications for subject safety and lead-time bias. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(4):372-379.

6. Tidbury P, Singer A, Jenkins D. CIN 3: the role of lesion size in invasion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99(7):583-586.

1. Pruitt SL, Schootman M. Geographic disparity, area poverty, and human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):525-533.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Frequently asked questions about HPV vaccine safety. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/Vaccines/HPV/hpv_faqs.html. Accessed February 1, 2011.

3. Cox JT, Moriarty AT, Castle PE. Commentary on: Statement on HPV DNA test utilization. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37(7):471-474.

4. Cox JT. More questions about the accuracy of colposcopy: what does this mean for cervical cancer prevention? Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1266-1267.

5. Sherman ME, Wang SS, Tarone R, Rich L, Schiffman M. Histopathologic extent of CIN 3 lesions in ALTS: implications for subject safety and lead-time bias. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(4):372-379.

6. Tidbury P, Singer A, Jenkins D. CIN 3: the role of lesion size in invasion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99(7):583-586.

Is the HPV test effective as the primary screen for cervical cancer?

Until now, the HPV test has been evaluated primarily as an adjunct to the Pap test and not as the primary screen for cervical cancer. In this randomized trial from Finland, 58,076 women 30 to 60 years old were invited to participate in a routine, population-based screening program for cervical cancer. Participants were randomized to primary screening with the HPV DNA test (hybrid capture 2) or to conventional cytology. In the group undergoing HPV testing, women who had a positive result were triaged to conventional cytology.

The HPV and conventional-cytology arms involved 95,600 and 95,700 woman-years of follow-up, respectively, and detected 76 and 53 cases of CIN 3 or higher. Six and eight cases, respectively, involved cancer.

The relative risk (RR) of CIN 3 or higher in the HPV arm versus conventional cytology was 1.44 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–2.05) among all women invited for screening and 1.77 (95% CI, 1.16–2.74) among those who attended. Among women who had a normal or negative HPV test, the RR of subsequent CIN 3 or greater was 0.28 (95% CI, 0.04–1.17).

The greatest strengths of this study are the 1:1 randomization of just over 58,000 women and the ability to link study participants to outcomes, over a 5-year period, using the comprehensive Finnish population database and cancer registry.

One concern that clinicians may have is whether the findings are applicable to a US population that is now rarely screened using conventional cytology (liquid-based cytology is the norm). That concern should be allayed by a large meta-analysis that found no difference in the sensitivity of liquid-based cytology versus conventional Pap testing.1

Although nearly one third of women invited to participate in screening did not do so, the two groups had comparable numbers of women deciding not to participate (9,588 in the HPV arm versus 9,818 in the conventional-cytology arm).

One variable limiting applicability to a US population is the lack of an organized screening program like the one in Finland.

Despite its large size, the study had limited statistical power to show the impact of the two screening modalities on the rate of cervical cancer, primarily because that rate is so low in the population screened. To determine that impact, the screening options need to be repeated for another round, with follow-up extended to 10 years.

I recommend that you follow current US guidelines and screen women 30 years and older with both the Pap and HPV tests and extend the screening interval to 3 years for women who have a negative result on both tests. Numerous studies support the overwhelming conclusion that HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening significantly increases detection of CIN 3 or higher and should reduce the woman’s subsequent risk of developing cervical cancer.—J. THOMAS COX, MD

Co-testing is the standard

US guidelines from the American Cancer Society (2002) and ACOG (2003, 2009) offer clinicians the option of screening women 30 years and older using both cytology and HPV testing—an approach known as “co-testing.” However, even though about 90% of the women who have a negative response to both tests can safely forgo further screening for at least 3 years, many clinicians screen them more frequently with co-testing, decreasing the cost-effectiveness of this option.2

The findings of Antilla and coworkers are in line with those of other authors. For example, Naucler and colleagues found that using the most sensitive test first (the HPV test), followed by reflex testing of positive HPV findings using the most specific test (the Pap), increased the sensitivity of screening for CIN 3 or greater by 30%, compared with screening with the Pap test alone.3 Other authors, including Ronco and coworkers and Sankaranarayanan and colleagues, have pointed to the superiority of either co-testing or HPV testing to use of the Pap test alone.4,5

1. Arbyn M, Bergeron C, Klinkhamer P, Martin-Hirsch P, Siebers Ag, Bulten J. Liquid compared with conventional cervical cytology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):167-177.

2. Saraiya M, Berkotwitz Z, Yabroff KR, Wideroff L, Kobrin S, Benard V. Cervical cancer screening with both human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou testing vs Papanicolaou testing alone: what screening intervals are physicians recommending? Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(11):977-985.

3. Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Efficacy of HPV DNA testing with cytology triage and/or repeat HPV DNA testing in primary cervical cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(2):88-99.

4. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(3):249-257.

5. Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1385-1394.

Until now, the HPV test has been evaluated primarily as an adjunct to the Pap test and not as the primary screen for cervical cancer. In this randomized trial from Finland, 58,076 women 30 to 60 years old were invited to participate in a routine, population-based screening program for cervical cancer. Participants were randomized to primary screening with the HPV DNA test (hybrid capture 2) or to conventional cytology. In the group undergoing HPV testing, women who had a positive result were triaged to conventional cytology.

The HPV and conventional-cytology arms involved 95,600 and 95,700 woman-years of follow-up, respectively, and detected 76 and 53 cases of CIN 3 or higher. Six and eight cases, respectively, involved cancer.

The relative risk (RR) of CIN 3 or higher in the HPV arm versus conventional cytology was 1.44 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–2.05) among all women invited for screening and 1.77 (95% CI, 1.16–2.74) among those who attended. Among women who had a normal or negative HPV test, the RR of subsequent CIN 3 or greater was 0.28 (95% CI, 0.04–1.17).

The greatest strengths of this study are the 1:1 randomization of just over 58,000 women and the ability to link study participants to outcomes, over a 5-year period, using the comprehensive Finnish population database and cancer registry.

One concern that clinicians may have is whether the findings are applicable to a US population that is now rarely screened using conventional cytology (liquid-based cytology is the norm). That concern should be allayed by a large meta-analysis that found no difference in the sensitivity of liquid-based cytology versus conventional Pap testing.1

Although nearly one third of women invited to participate in screening did not do so, the two groups had comparable numbers of women deciding not to participate (9,588 in the HPV arm versus 9,818 in the conventional-cytology arm).

One variable limiting applicability to a US population is the lack of an organized screening program like the one in Finland.

Despite its large size, the study had limited statistical power to show the impact of the two screening modalities on the rate of cervical cancer, primarily because that rate is so low in the population screened. To determine that impact, the screening options need to be repeated for another round, with follow-up extended to 10 years.

I recommend that you follow current US guidelines and screen women 30 years and older with both the Pap and HPV tests and extend the screening interval to 3 years for women who have a negative result on both tests. Numerous studies support the overwhelming conclusion that HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening significantly increases detection of CIN 3 or higher and should reduce the woman’s subsequent risk of developing cervical cancer.—J. THOMAS COX, MD

Co-testing is the standard

US guidelines from the American Cancer Society (2002) and ACOG (2003, 2009) offer clinicians the option of screening women 30 years and older using both cytology and HPV testing—an approach known as “co-testing.” However, even though about 90% of the women who have a negative response to both tests can safely forgo further screening for at least 3 years, many clinicians screen them more frequently with co-testing, decreasing the cost-effectiveness of this option.2

The findings of Antilla and coworkers are in line with those of other authors. For example, Naucler and colleagues found that using the most sensitive test first (the HPV test), followed by reflex testing of positive HPV findings using the most specific test (the Pap), increased the sensitivity of screening for CIN 3 or greater by 30%, compared with screening with the Pap test alone.3 Other authors, including Ronco and coworkers and Sankaranarayanan and colleagues, have pointed to the superiority of either co-testing or HPV testing to use of the Pap test alone.4,5

Until now, the HPV test has been evaluated primarily as an adjunct to the Pap test and not as the primary screen for cervical cancer. In this randomized trial from Finland, 58,076 women 30 to 60 years old were invited to participate in a routine, population-based screening program for cervical cancer. Participants were randomized to primary screening with the HPV DNA test (hybrid capture 2) or to conventional cytology. In the group undergoing HPV testing, women who had a positive result were triaged to conventional cytology.

The HPV and conventional-cytology arms involved 95,600 and 95,700 woman-years of follow-up, respectively, and detected 76 and 53 cases of CIN 3 or higher. Six and eight cases, respectively, involved cancer.

The relative risk (RR) of CIN 3 or higher in the HPV arm versus conventional cytology was 1.44 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–2.05) among all women invited for screening and 1.77 (95% CI, 1.16–2.74) among those who attended. Among women who had a normal or negative HPV test, the RR of subsequent CIN 3 or greater was 0.28 (95% CI, 0.04–1.17).

The greatest strengths of this study are the 1:1 randomization of just over 58,000 women and the ability to link study participants to outcomes, over a 5-year period, using the comprehensive Finnish population database and cancer registry.

One concern that clinicians may have is whether the findings are applicable to a US population that is now rarely screened using conventional cytology (liquid-based cytology is the norm). That concern should be allayed by a large meta-analysis that found no difference in the sensitivity of liquid-based cytology versus conventional Pap testing.1

Although nearly one third of women invited to participate in screening did not do so, the two groups had comparable numbers of women deciding not to participate (9,588 in the HPV arm versus 9,818 in the conventional-cytology arm).

One variable limiting applicability to a US population is the lack of an organized screening program like the one in Finland.

Despite its large size, the study had limited statistical power to show the impact of the two screening modalities on the rate of cervical cancer, primarily because that rate is so low in the population screened. To determine that impact, the screening options need to be repeated for another round, with follow-up extended to 10 years.

I recommend that you follow current US guidelines and screen women 30 years and older with both the Pap and HPV tests and extend the screening interval to 3 years for women who have a negative result on both tests. Numerous studies support the overwhelming conclusion that HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening significantly increases detection of CIN 3 or higher and should reduce the woman’s subsequent risk of developing cervical cancer.—J. THOMAS COX, MD

Co-testing is the standard

US guidelines from the American Cancer Society (2002) and ACOG (2003, 2009) offer clinicians the option of screening women 30 years and older using both cytology and HPV testing—an approach known as “co-testing.” However, even though about 90% of the women who have a negative response to both tests can safely forgo further screening for at least 3 years, many clinicians screen them more frequently with co-testing, decreasing the cost-effectiveness of this option.2

The findings of Antilla and coworkers are in line with those of other authors. For example, Naucler and colleagues found that using the most sensitive test first (the HPV test), followed by reflex testing of positive HPV findings using the most specific test (the Pap), increased the sensitivity of screening for CIN 3 or greater by 30%, compared with screening with the Pap test alone.3 Other authors, including Ronco and coworkers and Sankaranarayanan and colleagues, have pointed to the superiority of either co-testing or HPV testing to use of the Pap test alone.4,5

1. Arbyn M, Bergeron C, Klinkhamer P, Martin-Hirsch P, Siebers Ag, Bulten J. Liquid compared with conventional cervical cytology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):167-177.

2. Saraiya M, Berkotwitz Z, Yabroff KR, Wideroff L, Kobrin S, Benard V. Cervical cancer screening with both human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou testing vs Papanicolaou testing alone: what screening intervals are physicians recommending? Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(11):977-985.

3. Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Efficacy of HPV DNA testing with cytology triage and/or repeat HPV DNA testing in primary cervical cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(2):88-99.

4. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(3):249-257.

5. Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1385-1394.

1. Arbyn M, Bergeron C, Klinkhamer P, Martin-Hirsch P, Siebers Ag, Bulten J. Liquid compared with conventional cervical cytology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):167-177.

2. Saraiya M, Berkotwitz Z, Yabroff KR, Wideroff L, Kobrin S, Benard V. Cervical cancer screening with both human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou testing vs Papanicolaou testing alone: what screening intervals are physicians recommending? Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(11):977-985.

3. Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Efficacy of HPV DNA testing with cytology triage and/or repeat HPV DNA testing in primary cervical cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(2):88-99.

4. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(3):249-257.

5. Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1385-1394.

UPDATE: CERVICAL DISEASE

“Astonishment fatigue.” That phenomenon may be responsible for clinicians’ muted reaction to new ACOG guidelines on cervical cancer screening, which were released late last year. 1 Through a coincidence of timing, the new guidelines hit the airwaves just after the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force announced controversial changes to its recommendations on mammography. As a result, the cervical cytology guidelines seemed to dissolve into the stratosphere.

Or, perhaps, the cervical cancer screening guidelines slipped by with little fanfare because they were soundly based in evidence and, therefore, widely accepted among ObGyns. Even if that is the case, the medical community may not be familiar with the specific data behind the guideline changes. In this article, I discuss the evidence driving all major changes to the guidelines based on Level-A evidence. Changes based on Level-B or -C evidence are listed in TABLE 1 .

Hold off on cervical cancer screening until the patient is 21 years old

Screening before age 21 should be avoided because it may lead to unnecessary and harmful evaluation and treatment in women at very low risk of cancer.1

How different is this from the 2003 ACOG recommendation to begin screening within 3 years of first intercourse or at age 21, whichever comes first?

Very, very different. In fact, it is the most dramatic change in the 2009 screening recommendations.

It is even more striking in comparison with ACOG’s earlier recommendation—which prevailed from the late 1970s through 2002—to begin cervical screening at age 18 or at the onset of intercourse, whichever comes first.

The median age of first intercourse in the United States is 16 years. Until this latest change in guidelines, most young women began cervical screening during adolescence.

What’s wrong with screening adolescents? Don’t they acquire human papillomavirus (HPV)? (Yes.) And once they do, aren’t they at risk of cervical cancer? (Yes.)

Several variables support the delay of screening to age 21:

- the transience of most HPV infections

- the typically long natural history of carcinogenesis in the few young women in whom HPV might persist

- the adverse consequences of over-screening and over-management of adolescents who have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Let’s look more closely at these variables.

TABLE 1

Other ACOG cervical disease guidelines are based on Level-B and Level-C evidence*

| Recommendation | Level of evidence | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Test sexually active adolescents (i.e., females 21 years or younger) for sexually transmitted infection, and counsel them about safe sexual practices and contraception | B | These measures can be carried out without cervical cytology and, in the asymptomatic patient, without the introduction of a speculum |

| It is reasonable to discontinue cervical cancer screening in any woman 65 to 70 years old who has had three or more consecutive negative Pap tests and no abnormal tests in the past 10 years | B | |

| Continue annual screening for at least 20 years in any woman who has been treated for CIN 2, CIN 3, or cancer. This population remains at risk of persistent or recurrent disease for at least 20 years after treatment and after initial posttreatment surveillance | B | |

| Continue to screen any woman who has had a total hysterectomy if she has a history of CIN 2 or CIN 3 or if a negative history cannot be documented. This screening should continue even after initial post-treatment surveillance | B | Although the screening interval may ultimately be extended, we lack reliable data to support or refute the discontinuation of screening in this population |

| Inform the patient that annual gynecologic examination may still be appropriate even if cervical cytology is not assessed at each visit | C | |

| Screen any woman who has been immunized against HPV 16 and 18 as though she has not been immunized | C | |

| * Level-B recommendations are based on limited and inconsistent scientific evidence. Level-C recommendations are based primarily on consensus and expert opinion. | ||

HPV is common but usually resolves on its own

It’s common for young women to acquire HPV shortly after they become sexually active, but their immune system clears most infections within 1 or 2 years without the virus producing neoplastic changes.1

HPV detection peaks in the late teens and early 20s, when approximately 25% of women test positive for the virus, resulting in high rates of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) and HPV-positive, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US).2 These findings are mostly transient.2

Detection of CIN 3 does not peak until a woman reaches her late 20s, and the median detection of microinvasive cancer does not peak until she reaches her early 40s. These facts indicate that adolescents have the lowest risk of incipient cervical cancer but the highest risk of undergoing unnecessary procedures for HPV-related events—events that are highly likely to resolve without treatment.

From 1998 to 2006, an average of 14 cervical cancers occurred annually in women 15 to 19 years old, an incidence of only 1 or 2 cases of cervical cancer for every 1 million women in that age group ( TABLE 2 ).

TABLE 2

Incidence of invasive cervical carcinoma: United States, 1998-2003

| Age (y) | Average annual count | Incidence (95% CI) | Incidence as a percentage | Median age at diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ages | 10,846 | 8.9 (8.8–9.0) | 100 | 47 |

| 0–14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not applicable (NA) |

| 15–19 | 14 | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 0.1 | NA |

| 20–24 | 123 | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | 1.1 | NA |

| 25–29 | 543 | 6.9 (6.7–7.2) | 5.0 | NA |

| 30–34 | 1,045 | 12.3 (12.0–12.6) | 9.6 | NA |

| 35–39 | 1,350 | 14.6 (14.3–14.9) | 12.5 | NA |

| 40–44 | 1,534 | 16.3 (15.9–16.6) | 14.1 | NA |

| 45–49 | 1,323 | 15.4 (15.0–15.7) | 12.2 | NA |

| 50–59 | 1,958 | 14.5 (14.2–14.7) | 18.0 | NA |

| 60–69 | 1,352 | 14.8 (14.5–15.1) | 12.5 | NA |

| 70–79 | 1,008 | 12.9 (12.6–13.3) | 9.3 | NA |

| ≥80 | 595 | 11.2 (10.9–11.6) | 5.5 | NA |

| Source: Watson et al5 | ||||

In teens, screening does not reduce mortality

Even this low rate of cervical cancer might justify the screening of adolescents, provided such screening was shown to reduce the incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer in that age group. However, all data point to the opposite conclusion:

- The incidence of cervical cancer in this age group has not changed since the years between 1973 and 1977, a period that preceded the recommendation to begin screening at age 18 or first intercourse

- No data demonstrate a benefit of screening in women younger than 21 years in regard to future rates of CIN 2 and 3—or even that screening women 20 to 24 years old reduces the rate of cervical cancer in women 30 years or younger3

- CIN 2 and 3 do occur in adolescents, and the fear of delaying their diagnosis has driven much of the opposition to the guideline change—specifically, the omission of the option to begin screening within 3 years after first intercourse; however, even when high-grade CIN develops, spontaneous regression is common in this age group (e.g., 65% rate of regression of CIN 2 after 18 months; 75% after 36 months)