User login

Acute necrotizing esophagitis

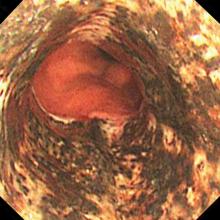

An 82-year-old man with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus presented to our emergency department with a 1-day history of confusion and coffee-ground emesis.

Biopsy study revealed necrosis of the esophageal mucosa. A diagnosis of acute necrotizing esophagitis was made.

ACUTE NECROTIZING ESOPHAGITIS

Acute necrotizing esophagitis is thought to arise from a combination of an ischemic insult to the esophagus, an impaired mucosal barrier system, and a backflow injury from chemical contents of gastric secretions.1 The tissue hypoperfusion derives from vasculopathy, hypotension, or malnutrition. It is associated with diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, alcohol abuse, cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, malignancy, antibiotic use, esophageal infections, and aortic dissection.

The esophagus has a diverse blood supply. The upper esophagus is supplied by the inferior thyroid arteries, the mid-esophagus by the bronchial, proper esophageal, and intercostal arteries, and the distal esophagus by the left gastric and left inferior phrenic arteries.1

KEY FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

The necrotic changes are prominent in the distal esophagus, which is more susceptible to ischemia and mucosal injury. The characteristic endoscopic finding is a diffuse black esophagus with a sharp transition to normal mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

The differential diagnosis includes melanosis, pseudomelanosis, malignant melanoma, acanthosis nigricans, coal dust deposition, caustic ingestion, radiation esophagitis, and infectious esophagitis caused by cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Candida albicans, or Klebsiella pneumoniae.2–4

TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

Avoidance of oral intake and gastric acid suppression with intravenous proton pump inhibitors are recommended to prevent additional injury of the esophageal mucosa.

The condition generally resolves with restored blood flow and treatment of any coexisting illness. However, it may be complicated by perforation (6.8%), mediastinitis (5.7%), or subsequent development of esophageal stricture (10.2%).5 Patients with esophageal stricture require endoscopic dilation after mucosal recovery.

The overall risk of death in acute necrotizing esophagitis is high (31.8%) and most often due to the underlying disease, such as sepsis, malignancy, cardiogenic shock, or hypovolemic shock.5 The mortality rate directly attributed to complications of acute necrotizing esophagitis is much lower (5.7%).5

- Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(26):3219–3225. pmid:20614476

- Khan HA. Coal dust deposition—rare cause of “black esophagus.” Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(10):2256. pmid:8855776

- Ertekin C, Alimoglu O, Akyildiz H, Guloglu R, Taviloglu K. The results of caustic ingestions. Hepatogastroenterology 2004; 51(59):1397–1400. pmid:15362762

- Kozlowski LM, Nigra TP. Esophageal acanthosis nigricans in association with adenocarcinoma from an unknown primary site. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26(2 pt 2):348–351. pmid:1569256

- Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42(1):29–38. doi:10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z

An 82-year-old man with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus presented to our emergency department with a 1-day history of confusion and coffee-ground emesis.

Biopsy study revealed necrosis of the esophageal mucosa. A diagnosis of acute necrotizing esophagitis was made.

ACUTE NECROTIZING ESOPHAGITIS

Acute necrotizing esophagitis is thought to arise from a combination of an ischemic insult to the esophagus, an impaired mucosal barrier system, and a backflow injury from chemical contents of gastric secretions.1 The tissue hypoperfusion derives from vasculopathy, hypotension, or malnutrition. It is associated with diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, alcohol abuse, cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, malignancy, antibiotic use, esophageal infections, and aortic dissection.

The esophagus has a diverse blood supply. The upper esophagus is supplied by the inferior thyroid arteries, the mid-esophagus by the bronchial, proper esophageal, and intercostal arteries, and the distal esophagus by the left gastric and left inferior phrenic arteries.1

KEY FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

The necrotic changes are prominent in the distal esophagus, which is more susceptible to ischemia and mucosal injury. The characteristic endoscopic finding is a diffuse black esophagus with a sharp transition to normal mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

The differential diagnosis includes melanosis, pseudomelanosis, malignant melanoma, acanthosis nigricans, coal dust deposition, caustic ingestion, radiation esophagitis, and infectious esophagitis caused by cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Candida albicans, or Klebsiella pneumoniae.2–4

TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

Avoidance of oral intake and gastric acid suppression with intravenous proton pump inhibitors are recommended to prevent additional injury of the esophageal mucosa.

The condition generally resolves with restored blood flow and treatment of any coexisting illness. However, it may be complicated by perforation (6.8%), mediastinitis (5.7%), or subsequent development of esophageal stricture (10.2%).5 Patients with esophageal stricture require endoscopic dilation after mucosal recovery.

The overall risk of death in acute necrotizing esophagitis is high (31.8%) and most often due to the underlying disease, such as sepsis, malignancy, cardiogenic shock, or hypovolemic shock.5 The mortality rate directly attributed to complications of acute necrotizing esophagitis is much lower (5.7%).5

An 82-year-old man with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus presented to our emergency department with a 1-day history of confusion and coffee-ground emesis.

Biopsy study revealed necrosis of the esophageal mucosa. A diagnosis of acute necrotizing esophagitis was made.

ACUTE NECROTIZING ESOPHAGITIS

Acute necrotizing esophagitis is thought to arise from a combination of an ischemic insult to the esophagus, an impaired mucosal barrier system, and a backflow injury from chemical contents of gastric secretions.1 The tissue hypoperfusion derives from vasculopathy, hypotension, or malnutrition. It is associated with diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, alcohol abuse, cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, malignancy, antibiotic use, esophageal infections, and aortic dissection.

The esophagus has a diverse blood supply. The upper esophagus is supplied by the inferior thyroid arteries, the mid-esophagus by the bronchial, proper esophageal, and intercostal arteries, and the distal esophagus by the left gastric and left inferior phrenic arteries.1

KEY FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

The necrotic changes are prominent in the distal esophagus, which is more susceptible to ischemia and mucosal injury. The characteristic endoscopic finding is a diffuse black esophagus with a sharp transition to normal mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

The differential diagnosis includes melanosis, pseudomelanosis, malignant melanoma, acanthosis nigricans, coal dust deposition, caustic ingestion, radiation esophagitis, and infectious esophagitis caused by cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Candida albicans, or Klebsiella pneumoniae.2–4

TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

Avoidance of oral intake and gastric acid suppression with intravenous proton pump inhibitors are recommended to prevent additional injury of the esophageal mucosa.

The condition generally resolves with restored blood flow and treatment of any coexisting illness. However, it may be complicated by perforation (6.8%), mediastinitis (5.7%), or subsequent development of esophageal stricture (10.2%).5 Patients with esophageal stricture require endoscopic dilation after mucosal recovery.

The overall risk of death in acute necrotizing esophagitis is high (31.8%) and most often due to the underlying disease, such as sepsis, malignancy, cardiogenic shock, or hypovolemic shock.5 The mortality rate directly attributed to complications of acute necrotizing esophagitis is much lower (5.7%).5

- Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(26):3219–3225. pmid:20614476

- Khan HA. Coal dust deposition—rare cause of “black esophagus.” Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(10):2256. pmid:8855776

- Ertekin C, Alimoglu O, Akyildiz H, Guloglu R, Taviloglu K. The results of caustic ingestions. Hepatogastroenterology 2004; 51(59):1397–1400. pmid:15362762

- Kozlowski LM, Nigra TP. Esophageal acanthosis nigricans in association with adenocarcinoma from an unknown primary site. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26(2 pt 2):348–351. pmid:1569256

- Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42(1):29–38. doi:10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z

- Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(26):3219–3225. pmid:20614476

- Khan HA. Coal dust deposition—rare cause of “black esophagus.” Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(10):2256. pmid:8855776

- Ertekin C, Alimoglu O, Akyildiz H, Guloglu R, Taviloglu K. The results of caustic ingestions. Hepatogastroenterology 2004; 51(59):1397–1400. pmid:15362762

- Kozlowski LM, Nigra TP. Esophageal acanthosis nigricans in association with adenocarcinoma from an unknown primary site. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26(2 pt 2):348–351. pmid:1569256

- Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42(1):29–38. doi:10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z

An unexpected cause of shoulder pain

A 58-year-old woman who sustained right-sided traumatic rib fractures after falling down stairs 8 months earlier presented with right shoulder pain that had been present for 6 months. She received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at another hospital, which were partially effective. Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck and right shoulder had shown no abnormalities.

On physical examination, her right scapula was found to protrude abnormally (ie, to “wing”) during forward flexion and abduction of the right arm (Figure 1). Electromyography showed evidence of right serratus anterior paralysis and denervation of the right long thoracic nerve, leading to a diagnosis of traumatic long thoracic nerve paralysis. A course of physical therapy was initiated to improve her symptoms.

LONG THORACIC NERVE PARALYSIS

Scapular winging is caused by dysfunction of any of the 3 main muscles that attach the scapula to the posterior thoracic wall—the serratus anterior, the trapezius, and the rhomboid. The problem is most often in the serratus anterior muscle, innervated by the long thoracic nerve, a pure motor nerve that originates from the fifth, sixth, and seventh cervical nerves and descends along the lateral thoracic wall.

Long thoracic nerve paralysis can have traumatic, nontraumatic, or iatrogenic causes. Traumatic injuries result from blunt trauma to the neck, shoulder girdle, and thorax, while nontraumatic causes include viral illness, toxic exposure, apical pulmonary tumor, and C7 radiculopathy.1–3 Iatrogenic injuries may be caused by mastectomy with axillary dissection, chest tube thoracostomy, first-rib resection, or scalenotomy, or occur after general anesthesia.1,2,4

Scapular winging due to paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle is accentuated by forward elevation and—particularly—by pushing against a wall, and the entire scapula is displaced more medially and superiorly.2 The compensatory muscular activity required for shoulder stability induces secondary shoulder pain.5

The diagnosis is often delayed, as the clinical presentation may mimic the symptoms of shoulder joint or rotator cuff pathology. Although physical therapy resolves the pain and improves the function of the arm, mild endurance deficits and asymptomatic scapular winging may persist. Tendon transfer surgery is considered if adequate recovery is not achieved after a 6- to-24-month course of physical therapy.2

- Vastamäki M, Kauppila LI. Etiologic factors in isolated paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle: a report of 197 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1993; 2:240–243.

- Martin RM, Fish DE. Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2008; 1:1–11.

- Toshkezi G, Dejesus J, Jabre JF, Hohler A, Davies K. Long thoracic neuropathy caused by an apical pulmonary tumor. J Neurosurg 2009; 110:754–757.

- Kauppila LI, Vastamäki M. Iatrogenic serratus anterior paralysis. Long-term outcome in 26 patients. Chest 1996; 109:31–34.

- Nath RK, Lyons AB, Bietz G. Microneurolysis and decompression of long thoracic nerve injury are effective in reversing scapular winging: long-term results in 50 cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8:25.

A 58-year-old woman who sustained right-sided traumatic rib fractures after falling down stairs 8 months earlier presented with right shoulder pain that had been present for 6 months. She received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at another hospital, which were partially effective. Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck and right shoulder had shown no abnormalities.

On physical examination, her right scapula was found to protrude abnormally (ie, to “wing”) during forward flexion and abduction of the right arm (Figure 1). Electromyography showed evidence of right serratus anterior paralysis and denervation of the right long thoracic nerve, leading to a diagnosis of traumatic long thoracic nerve paralysis. A course of physical therapy was initiated to improve her symptoms.

LONG THORACIC NERVE PARALYSIS

Scapular winging is caused by dysfunction of any of the 3 main muscles that attach the scapula to the posterior thoracic wall—the serratus anterior, the trapezius, and the rhomboid. The problem is most often in the serratus anterior muscle, innervated by the long thoracic nerve, a pure motor nerve that originates from the fifth, sixth, and seventh cervical nerves and descends along the lateral thoracic wall.

Long thoracic nerve paralysis can have traumatic, nontraumatic, or iatrogenic causes. Traumatic injuries result from blunt trauma to the neck, shoulder girdle, and thorax, while nontraumatic causes include viral illness, toxic exposure, apical pulmonary tumor, and C7 radiculopathy.1–3 Iatrogenic injuries may be caused by mastectomy with axillary dissection, chest tube thoracostomy, first-rib resection, or scalenotomy, or occur after general anesthesia.1,2,4

Scapular winging due to paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle is accentuated by forward elevation and—particularly—by pushing against a wall, and the entire scapula is displaced more medially and superiorly.2 The compensatory muscular activity required for shoulder stability induces secondary shoulder pain.5

The diagnosis is often delayed, as the clinical presentation may mimic the symptoms of shoulder joint or rotator cuff pathology. Although physical therapy resolves the pain and improves the function of the arm, mild endurance deficits and asymptomatic scapular winging may persist. Tendon transfer surgery is considered if adequate recovery is not achieved after a 6- to-24-month course of physical therapy.2

A 58-year-old woman who sustained right-sided traumatic rib fractures after falling down stairs 8 months earlier presented with right shoulder pain that had been present for 6 months. She received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at another hospital, which were partially effective. Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck and right shoulder had shown no abnormalities.

On physical examination, her right scapula was found to protrude abnormally (ie, to “wing”) during forward flexion and abduction of the right arm (Figure 1). Electromyography showed evidence of right serratus anterior paralysis and denervation of the right long thoracic nerve, leading to a diagnosis of traumatic long thoracic nerve paralysis. A course of physical therapy was initiated to improve her symptoms.

LONG THORACIC NERVE PARALYSIS

Scapular winging is caused by dysfunction of any of the 3 main muscles that attach the scapula to the posterior thoracic wall—the serratus anterior, the trapezius, and the rhomboid. The problem is most often in the serratus anterior muscle, innervated by the long thoracic nerve, a pure motor nerve that originates from the fifth, sixth, and seventh cervical nerves and descends along the lateral thoracic wall.

Long thoracic nerve paralysis can have traumatic, nontraumatic, or iatrogenic causes. Traumatic injuries result from blunt trauma to the neck, shoulder girdle, and thorax, while nontraumatic causes include viral illness, toxic exposure, apical pulmonary tumor, and C7 radiculopathy.1–3 Iatrogenic injuries may be caused by mastectomy with axillary dissection, chest tube thoracostomy, first-rib resection, or scalenotomy, or occur after general anesthesia.1,2,4

Scapular winging due to paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle is accentuated by forward elevation and—particularly—by pushing against a wall, and the entire scapula is displaced more medially and superiorly.2 The compensatory muscular activity required for shoulder stability induces secondary shoulder pain.5

The diagnosis is often delayed, as the clinical presentation may mimic the symptoms of shoulder joint or rotator cuff pathology. Although physical therapy resolves the pain and improves the function of the arm, mild endurance deficits and asymptomatic scapular winging may persist. Tendon transfer surgery is considered if adequate recovery is not achieved after a 6- to-24-month course of physical therapy.2

- Vastamäki M, Kauppila LI. Etiologic factors in isolated paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle: a report of 197 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1993; 2:240–243.

- Martin RM, Fish DE. Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2008; 1:1–11.

- Toshkezi G, Dejesus J, Jabre JF, Hohler A, Davies K. Long thoracic neuropathy caused by an apical pulmonary tumor. J Neurosurg 2009; 110:754–757.

- Kauppila LI, Vastamäki M. Iatrogenic serratus anterior paralysis. Long-term outcome in 26 patients. Chest 1996; 109:31–34.

- Nath RK, Lyons AB, Bietz G. Microneurolysis and decompression of long thoracic nerve injury are effective in reversing scapular winging: long-term results in 50 cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8:25.

- Vastamäki M, Kauppila LI. Etiologic factors in isolated paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle: a report of 197 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1993; 2:240–243.

- Martin RM, Fish DE. Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2008; 1:1–11.

- Toshkezi G, Dejesus J, Jabre JF, Hohler A, Davies K. Long thoracic neuropathy caused by an apical pulmonary tumor. J Neurosurg 2009; 110:754–757.

- Kauppila LI, Vastamäki M. Iatrogenic serratus anterior paralysis. Long-term outcome in 26 patients. Chest 1996; 109:31–34.

- Nath RK, Lyons AB, Bietz G. Microneurolysis and decompression of long thoracic nerve injury are effective in reversing scapular winging: long-term results in 50 cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8:25.