User login

Impact of Acne Vulgaris on Quality of Life and Self-esteem

Acne vulgaris predominantly occurs during puberty and can persist beyond 25 years of age, most commonly in women.1,2 Although acne does not cause physical impairment, it can be associated with a considerable psychosocial burden including increased levels of anxiety, anger, depression, and frustration, which in turn can affect vocational and academic performance, quality of life (QOL), and self-esteem.3

Quality of life measures provide valuable insight into the debilitating effects of acne.1 It has been suggested that acne patients may experience poor body image and low self-esteem as well as social isolation and constriction of activities.4 Self-esteem is a favorable and unfavorable attitude toward oneself.5 A marked emphasis has been placed on body image in society, fueled by external cues such as the media.3,6 This study was carried out to assess QOL and self-esteem in acne patients.

Methods

This prospective, hospital-based, cross-sectional, case-control study was conducted at The Oxford Medical College, Hospital & Research Center (Bangalore, India), over a period of 3 months. One hundred consecutive acne cases (age range, 12–45 years) and 100 age- and gender-matched controls who did not have any skin disease provided consent and were included in the analysis. Guardians gave consent for individuals who were younger than 18 years. Exclusion criteria for cases included a medical disorder (eg, epilepsy, diabetes mellitus, hypertension) or medications that would likely interfere with acne assessment.

The cases and controls were administered a semistructured questionnaire to collect sociodemographic details. Acne was graded for the predominant lesions, QOL was assessed using the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) and World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) scale, and self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES). The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Acne Grading

Acne was graded according to the predominant lesions using the following criteria: grade 1=comedones and occasional papules; grade 2=papules, comedones, and few pustules; grade 3=predominant pustules, nodules, and abscesses; and grade 4=mainly cysts, abscesses, and widespread scarring.1

Quality of Life Assessment

The CADI questionnaire was used to assess the level of disability caused by acne.6 It is a 5-item questionnaire with scores ranging from 0 to 3 for a total maximum score of 15 and minimum score of 0. Total scores were classified as low (0–4), medium (5–9), and high (10–15).7

The WHOQOL-BREF is a self-reported questionnaire containing 26 items that make up the 4 domains of physical health (7 items), psychological health (6 items), social relationships (3 items), and environment (8 items); there also are 2 single questions regarding the overall perception of QOL and health. Questions were scored on aseries of 5-point scales with higher scores denoting better QOL.8

Self-esteem Assessment

The RSES uses a 5-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree to rate a series of 10 statements. The total score ranges from 0 to 30. Scores less than 15 suggest low self-esteem, while scores of 15 and greater indicate high self-esteem.5

Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistical methods. A χ2 test was used for categorical data, and a Student t test and an analysis of variance were used for continuous data.

Results

The study consisted of 100 cases and 100 controls. The mean age was 21 years. The majority of cases reported an age of onset of acne of 11 to 20 years (66%), were predominantly female (58%) from rural backgrounds, and had a family history of acne (68%). The majority of lesions ceased within 24 months (60%). The face was the most commonly involved area (80%) and papules were the most prevalent lesion type (62%).

Cases predominantly had grade 2 acne (46%), and there was medium to high impairment in QOL according to CADI scores.

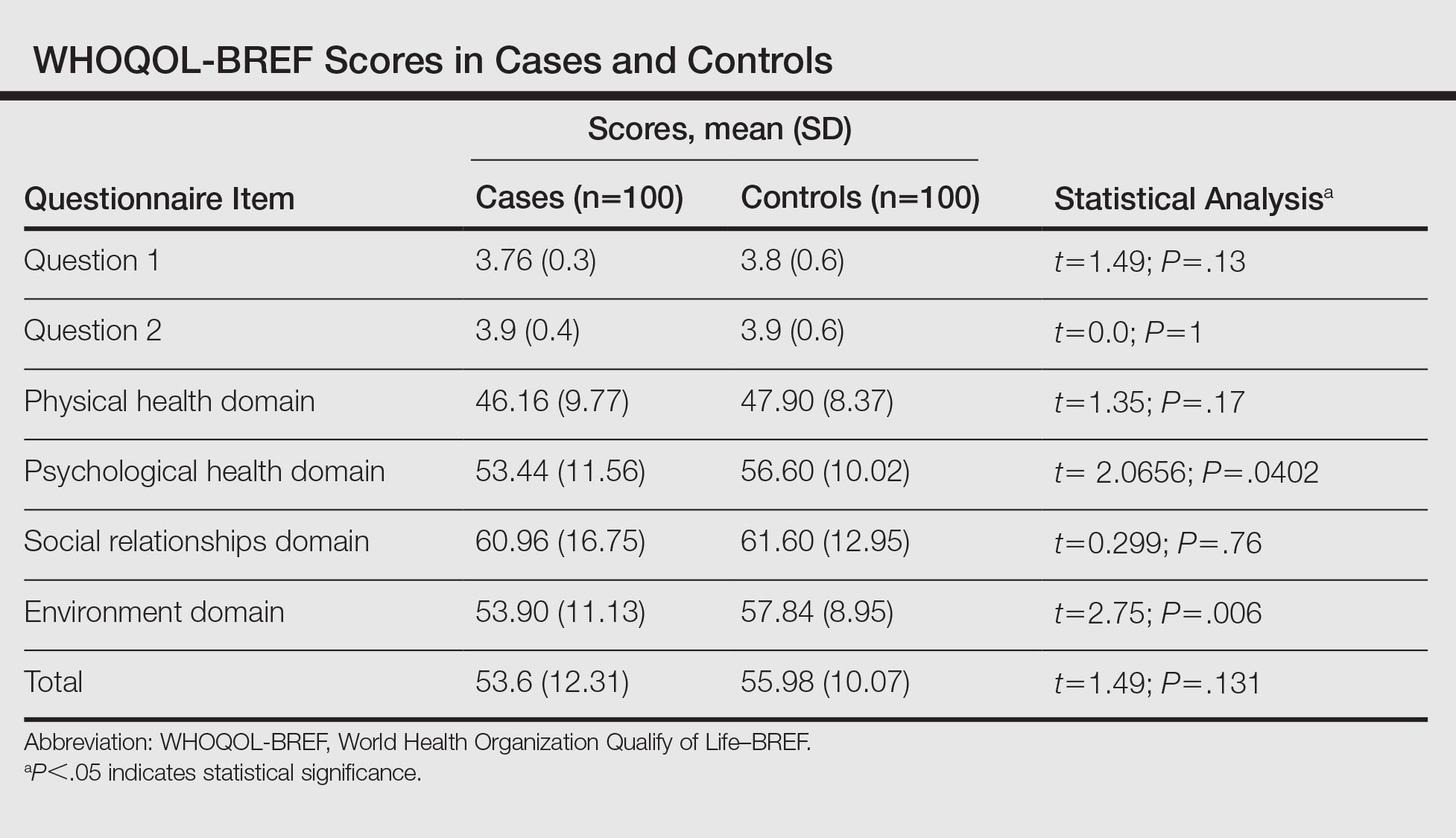

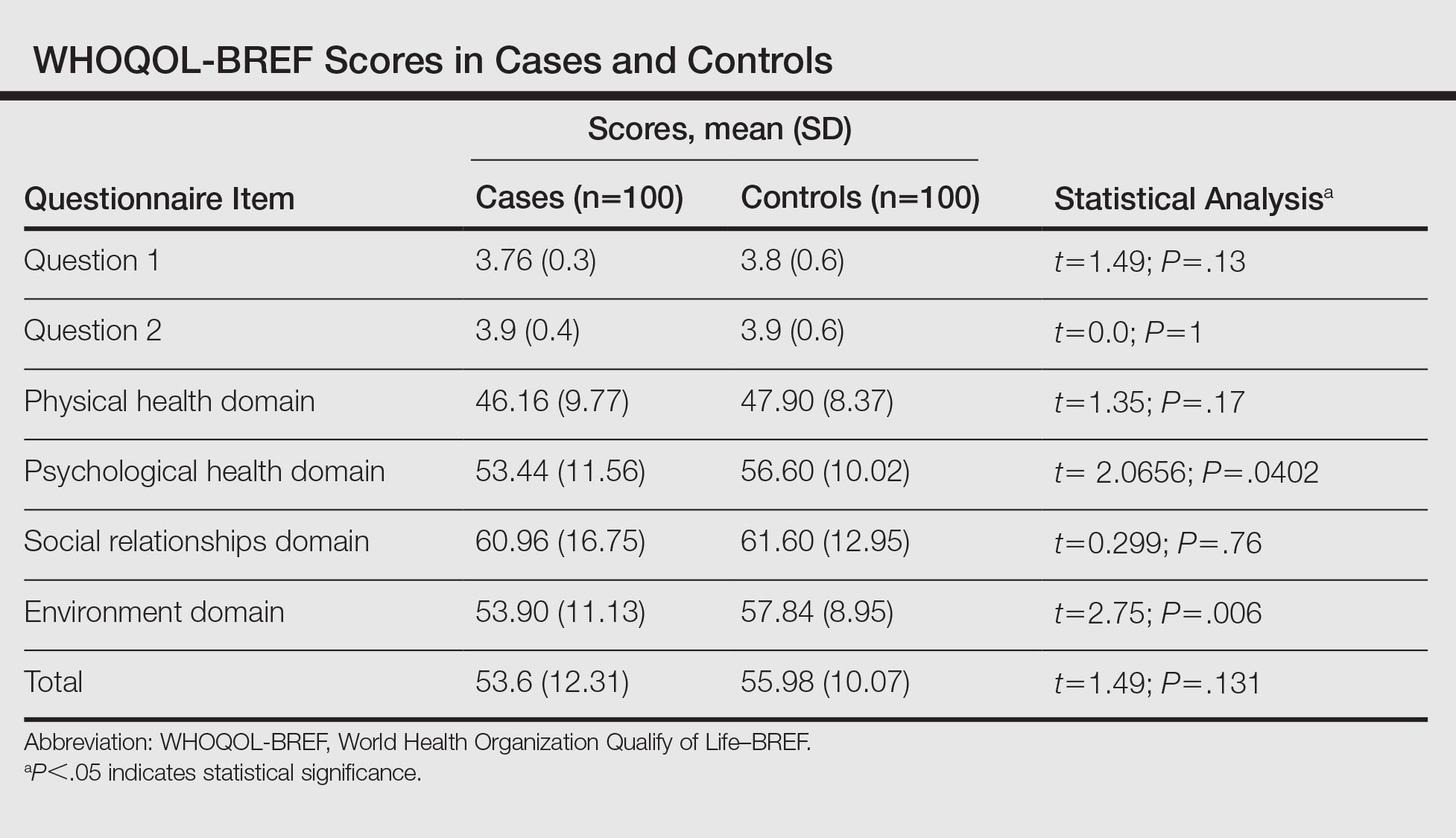

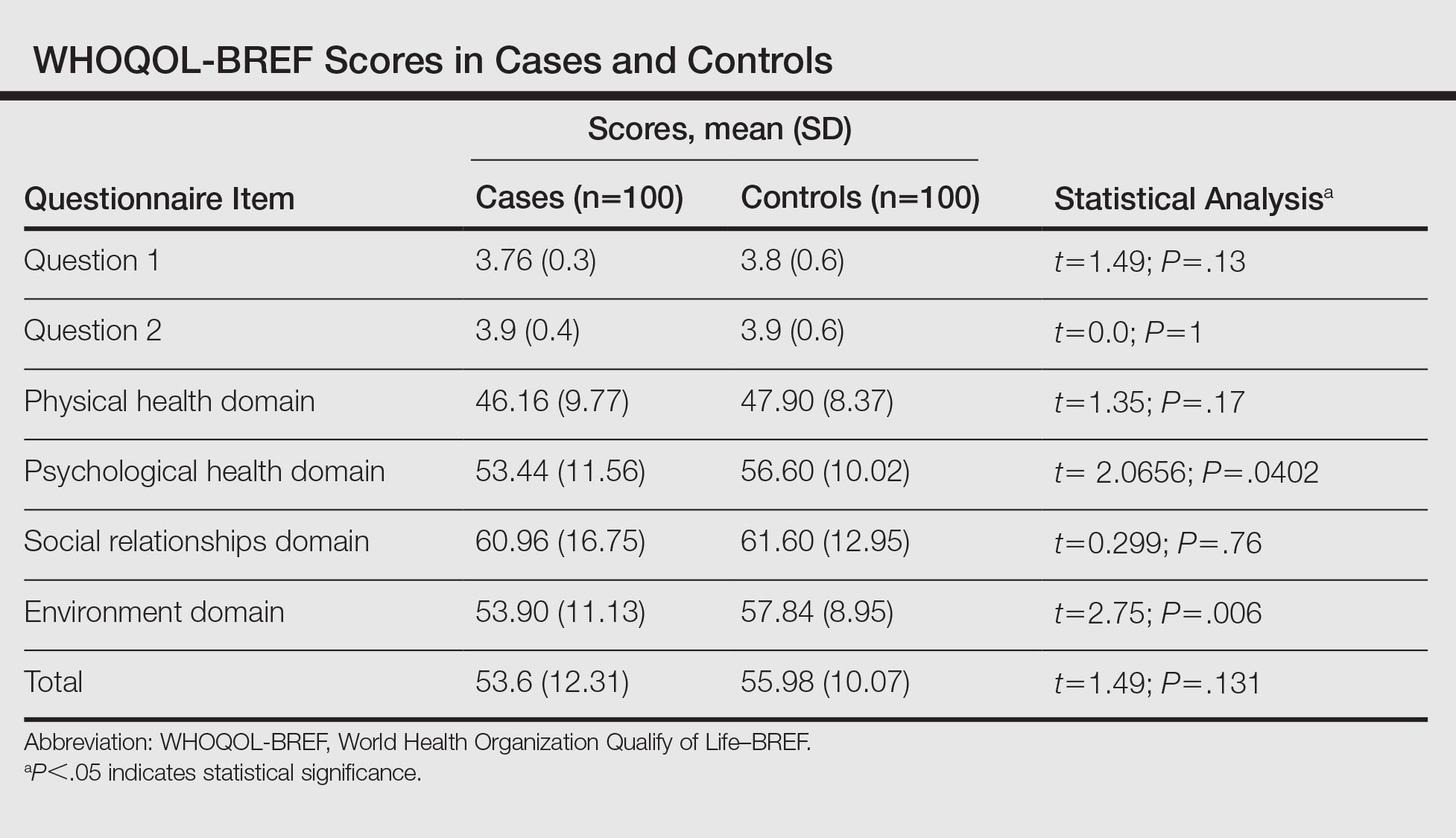

The scores for all the domains of the WHOQOL-BREF as well as the total score were lower in cases compared to controls (Table). There was a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in the psychological (P=.0402) and environment (P=.006) domains.

The RSES mean (SD) score was higher in controls (19.74 [4.23]) than in cases (15.72 [5.06]) and was statistically significant (P<.0001). Low self-esteem was noted in 38% of cases and 16% of controls, and high self-esteem was noted in 62% and 84%, respectively.

In reviewing the correlation between acne severity, CADI, WHOQOL-BREF, and RSES scores, we found a positive correlation between acne severity and CADI scores (R=0.51), which implies that as the severity of acne worsens, the QOL impairment increases. There was a negative correlation between acne severity, WHOQOL-BREF score (R=–0.13), and RSES score (R=–0.18), which showed that as the severity of acne increases, QOL and self-esteem decrease. We observed that as the grade of acne increases, there is a statistically significant impairment in the QOL according to CADI (P<.001), while there is a reduction in QOL and self-esteem according to WHOQOL-BREF and RSES, respectively (P>.05).

Comment

Patients are more likely to develop acne than any other skin disease in their lifetime. Only in recent years has the psychodermatologic literature begun to address the possibility of acne having a psychological and emotional impact.4 Although the cause-and-effect relationship between acne and psychological trauma has been debated for decades, only recently has the measurement focus shifted from psychological correlates (eg, personality) and emotional triggers (eg, stress) to the effect of acne on patients’ QOL and self-esteem. This shift occurred as validated instruments for measuring disability, QOL, and self-esteem, specifically in patients with skin diseases, became available.9

In our study, the age of onset of acne was 11 to 20 years and it affected predominantly females (58%), which is in concordance with other studies, as acne develops in adolescence and subsides in adulthood.1,10 Acne is more common in females due to hormonal factors and use of cosmetics. We observed that the face (80%) was most frequently affected, followed by the back (14%) and chest (6%), which is similar to prior studies.1,10 Because the face plays an important role in body image, the presence of facial lesions may be unacceptable for patients and therefore they may present more frequently to dermatologists.

In our study, 68% of cases and 22% of controls had a family history of acne. A similar correlation also was noted in other studies, which suggests acne has an inherited predisposition due to involvement of the cytochrome P450-1A1 gene, CYP1A1, and steroid 21-hydroxylase, P-450-c21.1,11 We found 46% of cases had grade 2 acne and 36% had grade 1 acne, which was congruent with prior studies.12,13 Patients with severe acne are more likely to seek medical intervention in hospitals.

In our study, 58% of the cases had medium to high impairment in QOL according to CADI scores. We noticed as the severity of acne increased there was severe impairment in QOL. Similar findings have been found in studies that used other scales to assess QOL.1,6,9

In our study, 38% of cases and 16% of controls had low self-esteem, which was statistically significant (P<.0001). There was a negative correlation between the severity of acne and self-esteem. In a prior study of 240 professional college students, 53% had feelings of low self-esteem and 40% revealed they avoided social gatherings and interactions with the opposite sex because of their acne.14 In a questionnaire-based survey of 3775 students, it was observed that the presence of acne correlated with poor self-attitude in boys and poor self-worth in girls.3 We found patients with grade 1 acne had higher self-esteem as compared to other grades of acne. Similarly, a cross-sectional study by Uslu et al15 found a direct correlation between acne severity and lower self-esteem using the RSES questionnaire. Although acne may be viewed as a minor cosmetic issue, it can have a negative impact on self-esteem and interpersonal relationships. Many of the studies had not used a validated structured questionnaire to assess self-esteem and there is a paucity of literature in relation to acne and self-esteem.3,16,17

According to the WHOQOL-BREF, the psychological domain was affected more in cases than in controls, which was a statistically significant difference. One study observed that patients experience immediate psychological consequences of acne such as reduced self-esteem, poor self-image, self-consciousness, and embarrassment.3 These effects are exacerbated by taunting, stigmatization, and perceptions of scrutiny and being judged, causing patients to avoid interaction and social situations. Similarly, Pruthi and Babu18 observed that acne had an impact on the psychosocial aspects of adult females using the Dermatology Life Quality Index and CADI.

Financial resources, health and social care accessibility, and opportunities for acquiring new information and skills were the factors that were considered in the environment domain of the WHOQOL-BREF.8 We noted that the environment domain scores were significantly lower in cases than in controls. The cases could have had a detrimental effect on the latest opportunities in occupational functioning due to acne, and as most of the population was from a rural area, they were having less favorable circumstances in acquiring new information about the management of acne.

There was no statistically significant difference between cases and controls in the social and physical domains of the WHOQOL-BREF, which suggests that these fields do not influence QOL. Similarly, patients in Sarawak, Malaysia, were least affected in the domain of social functioning, which was likely attributed to the upbringing of this population encouraging stoicism.19

In the current study, QOL impairment showed a positive correlation with acne severity according to CADI scores; however, there was no significant difference between WHOQOL-BREF score and acne grading, which suggests that QOL impairment does not depend on severity of acne alone. Physical, psychological, social, and environment domains play an important role in impaired QOL. Hence, by using the WHOQOL-BREF we can evaluate the actual domain that is adversely affected by acne and can be treated with a holistic approach. This point must be stressed in the training of medical faculty, as the treatment of acne should not be based on acne severity alone but also on the degree of QOL impairment.19

These results indicate that more data are required and there is a need to consider other variables that could play a role. This study was a hospital-based, cross-sectional study with a small sample group that cannot be generalized, which are limitations. Longitudinal follow-up of the cases before and after treatment was not done. The questionnaires helped us to detect psychosocial aspects but were insufficient to diagnose psychiatric comorbidity.

The strengths of this study include the use of a specific scale for the assessment of self-esteem. The usage of comprehensive (WHOQOL-BREF) and specific (CADI) scales to evaluate QOL has mutual advantage.

Conclusion

Acne vulgaris is a disease that can adversely affect an individual’s QOL and self-esteem. This study suggested the importance of screening for psychosocial problems in those who present for management of acne. It is important for dermatologists to be cautious about psychological problems in acne patients and be aware of the importance of basic psychosomatic treatment in conjunction with medical treatment in the management of acne.

- Durai PC, Nair DG. Acne vulgaris and quality of life among young adults in South India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:33-40.

- Karciauskiene J, Valiukeviciene S, Gollnick H, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of adolescent acne among schoolchildren in Lithuania: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:733-740.

- Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Do JE, Cho SM, In SI, et al. Psychosocial aspects of acne vulgaris: a community-based study with Korean adolescents. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:125-129.

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965.

- Ogedegbe EE, Henshaw EB. Severity and impact of acne vulgaris on the quality of life of adolescents in Nigeria. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:329-334.

- Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). Cardiff University website. sites.cardiff.ac.uk/dermatology/…of…/Cardiff-acne-disability-index-cadi/. Accessed July 21, 2016.

- WHO QOL-BREF: Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/76.pdf. Published December 1996. Accessed June 6, 2016.

- Lasek RJ, Chren MM. Acne vulgaris and the quality of life of adult dermatology patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:454-458.

- Adityan B, Thappa DM. Profile of acne vulgaris—a hospital-based study from South India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:272-278.

- Tasoula E, Gregoriou S, Chalikias J, et al. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece. results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:862-869.

- Agheai S, Mazaharinia N, Jafari P, et al. The Persian version of the Cardiff Acne Disability Index. reliability and validity study. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:80-82.

- Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, et al. The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:672-676.

- Goel S, Goel S. Clinico-psychological profile of acne vulgaris among professional students. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2012;3:175-178.

- Uslu G, Sendur N, Uslu M, et al. Acne: prevalence, perceptions and effects on psychological health among adolescents in Aydin, Turkey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:462-469.

- Ayer J, Burrows N. Acne: more than skin deep. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:500-506.

- Fried RG, Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and skin disease. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:657-664.

- Pruthi GK, Babu N. Physical and psychosocial impact of acne in adult females. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:26-29.

- Yap FB. Cardiff Acne Disability Index in Sarawak, Malaysia. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:158-161.

Acne vulgaris predominantly occurs during puberty and can persist beyond 25 years of age, most commonly in women.1,2 Although acne does not cause physical impairment, it can be associated with a considerable psychosocial burden including increased levels of anxiety, anger, depression, and frustration, which in turn can affect vocational and academic performance, quality of life (QOL), and self-esteem.3

Quality of life measures provide valuable insight into the debilitating effects of acne.1 It has been suggested that acne patients may experience poor body image and low self-esteem as well as social isolation and constriction of activities.4 Self-esteem is a favorable and unfavorable attitude toward oneself.5 A marked emphasis has been placed on body image in society, fueled by external cues such as the media.3,6 This study was carried out to assess QOL and self-esteem in acne patients.

Methods

This prospective, hospital-based, cross-sectional, case-control study was conducted at The Oxford Medical College, Hospital & Research Center (Bangalore, India), over a period of 3 months. One hundred consecutive acne cases (age range, 12–45 years) and 100 age- and gender-matched controls who did not have any skin disease provided consent and were included in the analysis. Guardians gave consent for individuals who were younger than 18 years. Exclusion criteria for cases included a medical disorder (eg, epilepsy, diabetes mellitus, hypertension) or medications that would likely interfere with acne assessment.

The cases and controls were administered a semistructured questionnaire to collect sociodemographic details. Acne was graded for the predominant lesions, QOL was assessed using the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) and World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) scale, and self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES). The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Acne Grading

Acne was graded according to the predominant lesions using the following criteria: grade 1=comedones and occasional papules; grade 2=papules, comedones, and few pustules; grade 3=predominant pustules, nodules, and abscesses; and grade 4=mainly cysts, abscesses, and widespread scarring.1

Quality of Life Assessment

The CADI questionnaire was used to assess the level of disability caused by acne.6 It is a 5-item questionnaire with scores ranging from 0 to 3 for a total maximum score of 15 and minimum score of 0. Total scores were classified as low (0–4), medium (5–9), and high (10–15).7

The WHOQOL-BREF is a self-reported questionnaire containing 26 items that make up the 4 domains of physical health (7 items), psychological health (6 items), social relationships (3 items), and environment (8 items); there also are 2 single questions regarding the overall perception of QOL and health. Questions were scored on aseries of 5-point scales with higher scores denoting better QOL.8

Self-esteem Assessment

The RSES uses a 5-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree to rate a series of 10 statements. The total score ranges from 0 to 30. Scores less than 15 suggest low self-esteem, while scores of 15 and greater indicate high self-esteem.5

Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistical methods. A χ2 test was used for categorical data, and a Student t test and an analysis of variance were used for continuous data.

Results

The study consisted of 100 cases and 100 controls. The mean age was 21 years. The majority of cases reported an age of onset of acne of 11 to 20 years (66%), were predominantly female (58%) from rural backgrounds, and had a family history of acne (68%). The majority of lesions ceased within 24 months (60%). The face was the most commonly involved area (80%) and papules were the most prevalent lesion type (62%).

Cases predominantly had grade 2 acne (46%), and there was medium to high impairment in QOL according to CADI scores.

The scores for all the domains of the WHOQOL-BREF as well as the total score were lower in cases compared to controls (Table). There was a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in the psychological (P=.0402) and environment (P=.006) domains.

The RSES mean (SD) score was higher in controls (19.74 [4.23]) than in cases (15.72 [5.06]) and was statistically significant (P<.0001). Low self-esteem was noted in 38% of cases and 16% of controls, and high self-esteem was noted in 62% and 84%, respectively.

In reviewing the correlation between acne severity, CADI, WHOQOL-BREF, and RSES scores, we found a positive correlation between acne severity and CADI scores (R=0.51), which implies that as the severity of acne worsens, the QOL impairment increases. There was a negative correlation between acne severity, WHOQOL-BREF score (R=–0.13), and RSES score (R=–0.18), which showed that as the severity of acne increases, QOL and self-esteem decrease. We observed that as the grade of acne increases, there is a statistically significant impairment in the QOL according to CADI (P<.001), while there is a reduction in QOL and self-esteem according to WHOQOL-BREF and RSES, respectively (P>.05).

Comment

Patients are more likely to develop acne than any other skin disease in their lifetime. Only in recent years has the psychodermatologic literature begun to address the possibility of acne having a psychological and emotional impact.4 Although the cause-and-effect relationship between acne and psychological trauma has been debated for decades, only recently has the measurement focus shifted from psychological correlates (eg, personality) and emotional triggers (eg, stress) to the effect of acne on patients’ QOL and self-esteem. This shift occurred as validated instruments for measuring disability, QOL, and self-esteem, specifically in patients with skin diseases, became available.9

In our study, the age of onset of acne was 11 to 20 years and it affected predominantly females (58%), which is in concordance with other studies, as acne develops in adolescence and subsides in adulthood.1,10 Acne is more common in females due to hormonal factors and use of cosmetics. We observed that the face (80%) was most frequently affected, followed by the back (14%) and chest (6%), which is similar to prior studies.1,10 Because the face plays an important role in body image, the presence of facial lesions may be unacceptable for patients and therefore they may present more frequently to dermatologists.

In our study, 68% of cases and 22% of controls had a family history of acne. A similar correlation also was noted in other studies, which suggests acne has an inherited predisposition due to involvement of the cytochrome P450-1A1 gene, CYP1A1, and steroid 21-hydroxylase, P-450-c21.1,11 We found 46% of cases had grade 2 acne and 36% had grade 1 acne, which was congruent with prior studies.12,13 Patients with severe acne are more likely to seek medical intervention in hospitals.

In our study, 58% of the cases had medium to high impairment in QOL according to CADI scores. We noticed as the severity of acne increased there was severe impairment in QOL. Similar findings have been found in studies that used other scales to assess QOL.1,6,9

In our study, 38% of cases and 16% of controls had low self-esteem, which was statistically significant (P<.0001). There was a negative correlation between the severity of acne and self-esteem. In a prior study of 240 professional college students, 53% had feelings of low self-esteem and 40% revealed they avoided social gatherings and interactions with the opposite sex because of their acne.14 In a questionnaire-based survey of 3775 students, it was observed that the presence of acne correlated with poor self-attitude in boys and poor self-worth in girls.3 We found patients with grade 1 acne had higher self-esteem as compared to other grades of acne. Similarly, a cross-sectional study by Uslu et al15 found a direct correlation between acne severity and lower self-esteem using the RSES questionnaire. Although acne may be viewed as a minor cosmetic issue, it can have a negative impact on self-esteem and interpersonal relationships. Many of the studies had not used a validated structured questionnaire to assess self-esteem and there is a paucity of literature in relation to acne and self-esteem.3,16,17

According to the WHOQOL-BREF, the psychological domain was affected more in cases than in controls, which was a statistically significant difference. One study observed that patients experience immediate psychological consequences of acne such as reduced self-esteem, poor self-image, self-consciousness, and embarrassment.3 These effects are exacerbated by taunting, stigmatization, and perceptions of scrutiny and being judged, causing patients to avoid interaction and social situations. Similarly, Pruthi and Babu18 observed that acne had an impact on the psychosocial aspects of adult females using the Dermatology Life Quality Index and CADI.

Financial resources, health and social care accessibility, and opportunities for acquiring new information and skills were the factors that were considered in the environment domain of the WHOQOL-BREF.8 We noted that the environment domain scores were significantly lower in cases than in controls. The cases could have had a detrimental effect on the latest opportunities in occupational functioning due to acne, and as most of the population was from a rural area, they were having less favorable circumstances in acquiring new information about the management of acne.

There was no statistically significant difference between cases and controls in the social and physical domains of the WHOQOL-BREF, which suggests that these fields do not influence QOL. Similarly, patients in Sarawak, Malaysia, were least affected in the domain of social functioning, which was likely attributed to the upbringing of this population encouraging stoicism.19

In the current study, QOL impairment showed a positive correlation with acne severity according to CADI scores; however, there was no significant difference between WHOQOL-BREF score and acne grading, which suggests that QOL impairment does not depend on severity of acne alone. Physical, psychological, social, and environment domains play an important role in impaired QOL. Hence, by using the WHOQOL-BREF we can evaluate the actual domain that is adversely affected by acne and can be treated with a holistic approach. This point must be stressed in the training of medical faculty, as the treatment of acne should not be based on acne severity alone but also on the degree of QOL impairment.19

These results indicate that more data are required and there is a need to consider other variables that could play a role. This study was a hospital-based, cross-sectional study with a small sample group that cannot be generalized, which are limitations. Longitudinal follow-up of the cases before and after treatment was not done. The questionnaires helped us to detect psychosocial aspects but were insufficient to diagnose psychiatric comorbidity.

The strengths of this study include the use of a specific scale for the assessment of self-esteem. The usage of comprehensive (WHOQOL-BREF) and specific (CADI) scales to evaluate QOL has mutual advantage.

Conclusion

Acne vulgaris is a disease that can adversely affect an individual’s QOL and self-esteem. This study suggested the importance of screening for psychosocial problems in those who present for management of acne. It is important for dermatologists to be cautious about psychological problems in acne patients and be aware of the importance of basic psychosomatic treatment in conjunction with medical treatment in the management of acne.

Acne vulgaris predominantly occurs during puberty and can persist beyond 25 years of age, most commonly in women.1,2 Although acne does not cause physical impairment, it can be associated with a considerable psychosocial burden including increased levels of anxiety, anger, depression, and frustration, which in turn can affect vocational and academic performance, quality of life (QOL), and self-esteem.3

Quality of life measures provide valuable insight into the debilitating effects of acne.1 It has been suggested that acne patients may experience poor body image and low self-esteem as well as social isolation and constriction of activities.4 Self-esteem is a favorable and unfavorable attitude toward oneself.5 A marked emphasis has been placed on body image in society, fueled by external cues such as the media.3,6 This study was carried out to assess QOL and self-esteem in acne patients.

Methods

This prospective, hospital-based, cross-sectional, case-control study was conducted at The Oxford Medical College, Hospital & Research Center (Bangalore, India), over a period of 3 months. One hundred consecutive acne cases (age range, 12–45 years) and 100 age- and gender-matched controls who did not have any skin disease provided consent and were included in the analysis. Guardians gave consent for individuals who were younger than 18 years. Exclusion criteria for cases included a medical disorder (eg, epilepsy, diabetes mellitus, hypertension) or medications that would likely interfere with acne assessment.

The cases and controls were administered a semistructured questionnaire to collect sociodemographic details. Acne was graded for the predominant lesions, QOL was assessed using the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) and World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) scale, and self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES). The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Acne Grading

Acne was graded according to the predominant lesions using the following criteria: grade 1=comedones and occasional papules; grade 2=papules, comedones, and few pustules; grade 3=predominant pustules, nodules, and abscesses; and grade 4=mainly cysts, abscesses, and widespread scarring.1

Quality of Life Assessment

The CADI questionnaire was used to assess the level of disability caused by acne.6 It is a 5-item questionnaire with scores ranging from 0 to 3 for a total maximum score of 15 and minimum score of 0. Total scores were classified as low (0–4), medium (5–9), and high (10–15).7

The WHOQOL-BREF is a self-reported questionnaire containing 26 items that make up the 4 domains of physical health (7 items), psychological health (6 items), social relationships (3 items), and environment (8 items); there also are 2 single questions regarding the overall perception of QOL and health. Questions were scored on aseries of 5-point scales with higher scores denoting better QOL.8

Self-esteem Assessment

The RSES uses a 5-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree to rate a series of 10 statements. The total score ranges from 0 to 30. Scores less than 15 suggest low self-esteem, while scores of 15 and greater indicate high self-esteem.5

Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistical methods. A χ2 test was used for categorical data, and a Student t test and an analysis of variance were used for continuous data.

Results

The study consisted of 100 cases and 100 controls. The mean age was 21 years. The majority of cases reported an age of onset of acne of 11 to 20 years (66%), were predominantly female (58%) from rural backgrounds, and had a family history of acne (68%). The majority of lesions ceased within 24 months (60%). The face was the most commonly involved area (80%) and papules were the most prevalent lesion type (62%).

Cases predominantly had grade 2 acne (46%), and there was medium to high impairment in QOL according to CADI scores.

The scores for all the domains of the WHOQOL-BREF as well as the total score were lower in cases compared to controls (Table). There was a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in the psychological (P=.0402) and environment (P=.006) domains.

The RSES mean (SD) score was higher in controls (19.74 [4.23]) than in cases (15.72 [5.06]) and was statistically significant (P<.0001). Low self-esteem was noted in 38% of cases and 16% of controls, and high self-esteem was noted in 62% and 84%, respectively.

In reviewing the correlation between acne severity, CADI, WHOQOL-BREF, and RSES scores, we found a positive correlation between acne severity and CADI scores (R=0.51), which implies that as the severity of acne worsens, the QOL impairment increases. There was a negative correlation between acne severity, WHOQOL-BREF score (R=–0.13), and RSES score (R=–0.18), which showed that as the severity of acne increases, QOL and self-esteem decrease. We observed that as the grade of acne increases, there is a statistically significant impairment in the QOL according to CADI (P<.001), while there is a reduction in QOL and self-esteem according to WHOQOL-BREF and RSES, respectively (P>.05).

Comment

Patients are more likely to develop acne than any other skin disease in their lifetime. Only in recent years has the psychodermatologic literature begun to address the possibility of acne having a psychological and emotional impact.4 Although the cause-and-effect relationship between acne and psychological trauma has been debated for decades, only recently has the measurement focus shifted from psychological correlates (eg, personality) and emotional triggers (eg, stress) to the effect of acne on patients’ QOL and self-esteem. This shift occurred as validated instruments for measuring disability, QOL, and self-esteem, specifically in patients with skin diseases, became available.9

In our study, the age of onset of acne was 11 to 20 years and it affected predominantly females (58%), which is in concordance with other studies, as acne develops in adolescence and subsides in adulthood.1,10 Acne is more common in females due to hormonal factors and use of cosmetics. We observed that the face (80%) was most frequently affected, followed by the back (14%) and chest (6%), which is similar to prior studies.1,10 Because the face plays an important role in body image, the presence of facial lesions may be unacceptable for patients and therefore they may present more frequently to dermatologists.

In our study, 68% of cases and 22% of controls had a family history of acne. A similar correlation also was noted in other studies, which suggests acne has an inherited predisposition due to involvement of the cytochrome P450-1A1 gene, CYP1A1, and steroid 21-hydroxylase, P-450-c21.1,11 We found 46% of cases had grade 2 acne and 36% had grade 1 acne, which was congruent with prior studies.12,13 Patients with severe acne are more likely to seek medical intervention in hospitals.

In our study, 58% of the cases had medium to high impairment in QOL according to CADI scores. We noticed as the severity of acne increased there was severe impairment in QOL. Similar findings have been found in studies that used other scales to assess QOL.1,6,9

In our study, 38% of cases and 16% of controls had low self-esteem, which was statistically significant (P<.0001). There was a negative correlation between the severity of acne and self-esteem. In a prior study of 240 professional college students, 53% had feelings of low self-esteem and 40% revealed they avoided social gatherings and interactions with the opposite sex because of their acne.14 In a questionnaire-based survey of 3775 students, it was observed that the presence of acne correlated with poor self-attitude in boys and poor self-worth in girls.3 We found patients with grade 1 acne had higher self-esteem as compared to other grades of acne. Similarly, a cross-sectional study by Uslu et al15 found a direct correlation between acne severity and lower self-esteem using the RSES questionnaire. Although acne may be viewed as a minor cosmetic issue, it can have a negative impact on self-esteem and interpersonal relationships. Many of the studies had not used a validated structured questionnaire to assess self-esteem and there is a paucity of literature in relation to acne and self-esteem.3,16,17

According to the WHOQOL-BREF, the psychological domain was affected more in cases than in controls, which was a statistically significant difference. One study observed that patients experience immediate psychological consequences of acne such as reduced self-esteem, poor self-image, self-consciousness, and embarrassment.3 These effects are exacerbated by taunting, stigmatization, and perceptions of scrutiny and being judged, causing patients to avoid interaction and social situations. Similarly, Pruthi and Babu18 observed that acne had an impact on the psychosocial aspects of adult females using the Dermatology Life Quality Index and CADI.

Financial resources, health and social care accessibility, and opportunities for acquiring new information and skills were the factors that were considered in the environment domain of the WHOQOL-BREF.8 We noted that the environment domain scores were significantly lower in cases than in controls. The cases could have had a detrimental effect on the latest opportunities in occupational functioning due to acne, and as most of the population was from a rural area, they were having less favorable circumstances in acquiring new information about the management of acne.

There was no statistically significant difference between cases and controls in the social and physical domains of the WHOQOL-BREF, which suggests that these fields do not influence QOL. Similarly, patients in Sarawak, Malaysia, were least affected in the domain of social functioning, which was likely attributed to the upbringing of this population encouraging stoicism.19

In the current study, QOL impairment showed a positive correlation with acne severity according to CADI scores; however, there was no significant difference between WHOQOL-BREF score and acne grading, which suggests that QOL impairment does not depend on severity of acne alone. Physical, psychological, social, and environment domains play an important role in impaired QOL. Hence, by using the WHOQOL-BREF we can evaluate the actual domain that is adversely affected by acne and can be treated with a holistic approach. This point must be stressed in the training of medical faculty, as the treatment of acne should not be based on acne severity alone but also on the degree of QOL impairment.19

These results indicate that more data are required and there is a need to consider other variables that could play a role. This study was a hospital-based, cross-sectional study with a small sample group that cannot be generalized, which are limitations. Longitudinal follow-up of the cases before and after treatment was not done. The questionnaires helped us to detect psychosocial aspects but were insufficient to diagnose psychiatric comorbidity.

The strengths of this study include the use of a specific scale for the assessment of self-esteem. The usage of comprehensive (WHOQOL-BREF) and specific (CADI) scales to evaluate QOL has mutual advantage.

Conclusion

Acne vulgaris is a disease that can adversely affect an individual’s QOL and self-esteem. This study suggested the importance of screening for psychosocial problems in those who present for management of acne. It is important for dermatologists to be cautious about psychological problems in acne patients and be aware of the importance of basic psychosomatic treatment in conjunction with medical treatment in the management of acne.

- Durai PC, Nair DG. Acne vulgaris and quality of life among young adults in South India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:33-40.

- Karciauskiene J, Valiukeviciene S, Gollnick H, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of adolescent acne among schoolchildren in Lithuania: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:733-740.

- Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Do JE, Cho SM, In SI, et al. Psychosocial aspects of acne vulgaris: a community-based study with Korean adolescents. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:125-129.

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965.

- Ogedegbe EE, Henshaw EB. Severity and impact of acne vulgaris on the quality of life of adolescents in Nigeria. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:329-334.

- Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). Cardiff University website. sites.cardiff.ac.uk/dermatology/…of…/Cardiff-acne-disability-index-cadi/. Accessed July 21, 2016.

- WHO QOL-BREF: Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/76.pdf. Published December 1996. Accessed June 6, 2016.

- Lasek RJ, Chren MM. Acne vulgaris and the quality of life of adult dermatology patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:454-458.

- Adityan B, Thappa DM. Profile of acne vulgaris—a hospital-based study from South India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:272-278.

- Tasoula E, Gregoriou S, Chalikias J, et al. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece. results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:862-869.

- Agheai S, Mazaharinia N, Jafari P, et al. The Persian version of the Cardiff Acne Disability Index. reliability and validity study. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:80-82.

- Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, et al. The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:672-676.

- Goel S, Goel S. Clinico-psychological profile of acne vulgaris among professional students. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2012;3:175-178.

- Uslu G, Sendur N, Uslu M, et al. Acne: prevalence, perceptions and effects on psychological health among adolescents in Aydin, Turkey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:462-469.

- Ayer J, Burrows N. Acne: more than skin deep. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:500-506.

- Fried RG, Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and skin disease. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:657-664.

- Pruthi GK, Babu N. Physical and psychosocial impact of acne in adult females. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:26-29.

- Yap FB. Cardiff Acne Disability Index in Sarawak, Malaysia. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:158-161.

- Durai PC, Nair DG. Acne vulgaris and quality of life among young adults in South India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:33-40.

- Karciauskiene J, Valiukeviciene S, Gollnick H, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of adolescent acne among schoolchildren in Lithuania: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:733-740.

- Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Do JE, Cho SM, In SI, et al. Psychosocial aspects of acne vulgaris: a community-based study with Korean adolescents. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:125-129.

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965.

- Ogedegbe EE, Henshaw EB. Severity and impact of acne vulgaris on the quality of life of adolescents in Nigeria. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:329-334.

- Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). Cardiff University website. sites.cardiff.ac.uk/dermatology/…of…/Cardiff-acne-disability-index-cadi/. Accessed July 21, 2016.

- WHO QOL-BREF: Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/76.pdf. Published December 1996. Accessed June 6, 2016.

- Lasek RJ, Chren MM. Acne vulgaris and the quality of life of adult dermatology patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:454-458.

- Adityan B, Thappa DM. Profile of acne vulgaris—a hospital-based study from South India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:272-278.

- Tasoula E, Gregoriou S, Chalikias J, et al. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece. results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:862-869.

- Agheai S, Mazaharinia N, Jafari P, et al. The Persian version of the Cardiff Acne Disability Index. reliability and validity study. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:80-82.

- Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, et al. The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:672-676.

- Goel S, Goel S. Clinico-psychological profile of acne vulgaris among professional students. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2012;3:175-178.

- Uslu G, Sendur N, Uslu M, et al. Acne: prevalence, perceptions and effects on psychological health among adolescents in Aydin, Turkey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:462-469.

- Ayer J, Burrows N. Acne: more than skin deep. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:500-506.

- Fried RG, Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and skin disease. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:657-664.

- Pruthi GK, Babu N. Physical and psychosocial impact of acne in adult females. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:26-29.

- Yap FB. Cardiff Acne Disability Index in Sarawak, Malaysia. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:158-161.

Practice Points

- Grading of acne will help with appropriate treatment, thus reducing the adverse psychological effects of the condition.

- Acne severity has a negative impact on quality of life and self-esteem.

- A sympathetic approach and basic psychosomatic treatment are necessary in the management of acne.